Abstract

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) and enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) are diarrheagenic pathotypes of E. coli that cause gastrointestinal disease with the potential for life-threatening sequelae. While certain EHEC and EPEC virulence mechanisms have been extensively studied, the factors that mediate host colonization remain to be properly defined. Previously, we identified four genes (ehaA, ehaB, ehaC, and ehaD) from the prototypic EHEC strain EDL933 that encode for proteins that belong to the autotransporter (AT) family. Here we have examined the prevalence of these genes, as well as several other AT-encoding genes, in a collection of EHEC and EPEC strains. We show that the complement of AT-encoding genes in EHEC and EPEC strains is variable, with some AT-encoding genes being highly prevalent. One previously uncharacterized AT-encoding gene, which we have termed ehaJ, was identified in 12/44 (27%) of EHEC and 2/20 (10%) of EPEC strains. The ehaJ gene lies immediately adjacent to a gene encoding a putative glycosyltransferase (referred to as egtA). Western blot analysis using an EhaJ-specific antibody indicated that EhaJ is glycosylated by EgtA. Expression of EhaJ in a recombinant E. coli strain, revealed EhaJ is located at the cell surface and in the presence of the egtA glycosyltransferase gene mediates strong biofilm formation in microtiter plate and flow cell assays. EhaJ also mediated adherence to a range of extracellular matrix proteins, however this occurred independent of glycosylation. We also demonstrate that EhaJ is expressed in a wild-type EPEC strain following in vitro growth. However, deletion of ehaJ did not significantly alter its adherence or biofilm properties. In summary, EhaJ is a new glycosylated AT protein from EPEC and EHEC. Further studies are required to elucidate the function of EhaJ in colonization and virulence.

Keywords: autotransporters, EHEC, EPEC, adhesin, biofilm

Introduction

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) are pathotypes of E. coli responsible for different pathologies in humans. EPEC are associated with small intestinal enteritis, and are a major cause of childhood diarrhea (Nataro and Kaper, 1998). STEC may also be associated with diarrhea, with some strains inducing more severe forms of enteritis such as hemorrhagic colitis, or extraintestinal disease such as hemolytic uremic syndrome (Karch et al., 2005). Such enhanced virulence STEC strains are referred to as enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). Both pathogens and their associated diseases are prevalent globally, with EPEC being a more significant cause of morbidity and mortality in developing countries (Nataro and Kaper, 1998; Bardiau et al., 2010). EPEC are generally considered to be communicable pathogens, being transmitted from human to human via the fecal-oral route. STEC (and therefore EHEC) are recognized zoonotic pathogens, with ruminant livestock being the principal host (Nataro and Kaper, 1998; Gyles, 2007). Food-borne transmission is important in the epidemiology of both EPEC and EHEC.

The molecular mechanisms associated with the colonization of human and animal hosts by EHEC and EPEC are not fully understood. The locus for enterocyte effacement (LEE) encodes a type three secretion system that is found in representative strains of both EHEC and EPEC. Whilst there are component protein and tissue tropism differences between LEE products (particularly for intimin, the key effector) for EPEC and EHEC, this mechanism appears functionally analogous in both pathogens in contributing to host cell attachment (Bardiau et al., 2010). In EHEC, several additional adhesins including Iha (Tarr et al., 2000), long polar fimbriae (Torres et al., 2002), curli (Uhlich et al., 2001), F9 fimbriae (Dziva et al., 2004; Low et al., 2006), Saa (Paton et al., 2001), and Efa1 (Nicholls et al., 2000) have been described. The roles and mechanisms of these adhesins (individually and/or in concert) in mediating host colonization remain to be fully elucidated. An improved understanding of EPEC and EHEC mucosal adherence may lead to development of interventions that will disrupt host colonization, be it colonization of humans as a prelude to pathogenesis, or colonization of livestock leading to carriage and maintenance of EHEC that can be subsequently transmitted to humans.

Several cell-surface proteins from the type V secreted autotransporter (AT) class have been characterized from EHEC. AT proteins are common to many Gram-negative pathogens and have diverse functions ranging from cell-associated adhesins to secreted toxins. All AT proteins have several common features: an N-terminal signal sequence, a passenger (α) domain that often encodes a virulence function and is either anchored to the cell surface or released into the external milieu and a translocation (β) domain that resides in the outer membrane (Jose et al., 1995; Henderson et al., 1998). Three broad categories of AT proteins have been defined in the literature based on domain-architecture: the serine protease AT proteins of Enterobacteriaceae (SPATEs), the AIDA-I type AT proteins and the trimeric AT adhesins (TAAs; Henderson et al., 2004). Among the AIDA-I group, the Ag43 protein (found in most E. coli strains), the TibA adhesin (associated with some enterotoxigenic E. coli) and the AIDA adhesin (associated with some diarrhea-causing E. coli) represent well characterized AT proteins that mediate aggregation, biofilm formation and can be glycosylated (Klemm et al., 2006). We previously described the identification and characterization of four AT proteins from E. coli EDL933 that belong to the AIDA-I group (Wells et al., 2008, 2009). Here we have extended this analysis to include a larger collection of EHEC and EPEC strains and also examined the prevalence of seven recently identified AT-encoding genes, two from the AIDA-I group (i.e., groups 6 and 7) and five from the TAA group (i.e., groups 1–5; Wells et al., 2010). In this study we have examined the relative prevalence of the various identified AT genes among EPEC and EHEC strains. We have also characterized the functional properties of a newly recognized AT, namely EhaJ.

Materials and Methods

Strains and media

The EHEC and EPEC strains used to assess the prevalence of AT-encoding genes were obtained from CSIRO Food and Nutritional Sciences, Queensland Health Forensic and Scientific Services, and the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries. EPEC MS455 is an O27:H6 strain from our laboratory collection and was positive for ehaA, ehaB, ehaC, ehaJ, and a group 4/5 AT-encoding gene by PCR screening. E. coli MS427 (MG1655flu) and OS56 [green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged MG1655flu] have been described previously (Kjaergaard et al., 2000; Sherlock et al., 2004). Cells were grown at 37°C on solid or in liquid Luria–Bertani (LB) media supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics unless otherwise stated. Where necessary, gene expression was induced with 0.2% arabinose.

DNA manipulations and genetic techniques

Genomic DNA was extracted from overnight cultures using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega) following the manufacturer’s procedure for Gram-negative bacteria. Plasmid DNA was isolated using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Restriction digests, ligations, and T4 polymerase treatment followed the manufacturer’s recommendations (New England BioLabs). PCR reactions for which high fidelity was required were performed using Expand High Fidelity Polymerase System (Roche) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Taq DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) was used for screening PCR reactions. DNA sequencing was performed by the Australian Equine Genetics Research Centre.

Prevalence of AT-encoding genes

The prevalence of each AT-encoding gene was assessed by PCR using primers specific to the translocation-encoding domain. Primers for ehaA, ehaB, ehaC, and ehaD were as previously described (Wells et al., 2008). Primers for the group 1, 2/3, 4/5, and 6/7 AT-encoding genes were as follows: group 1: 2105 (5′-gggtatggctctcaggtgaa) and 2106 (5′-agcatcagcaacagcatcac); group 2/3: 2107 (5′-acgyctgracagccagcagc) and 2108 (5′-gcggtctgctcgttgaagcg); group 4/5: 2109 (5′-caaatkcarmgtctggcgca) and 2110 (5′-cagacacccgagattcaccg); group 6/7: 2111 (5′-tgccayhtggtttgccgatg) and 2112 (5′-agayrrcctgtgcctgtggc). Prevalence of the ehaJ gene (which belongs to group 6) was assessed using primers 2442 (5′-aaggcggggaatgcagcgtc) and 2443 (5′-gcgtcaggctgagcgtgtgt). The groups were combined for initial screening where sufficient sequence conservation existed.

Construction of plasmids

The egtA–ehaJ and ehaJ genes were amplified by PCR from MS455 using primers designed from the available genome sequence of EPEC strain 2348/69. The following primers were used: egtA–ehaJ (141, 5′-cgcgctcgagataataaggagctttacagtgagtaataat and 142, 5′-cggcgaagcttctctgtattttaccaactgt); ehaJ (143, 5′-cgcgctcgagataataaggactaattcatgaacagaactt and 142). The PCR products containing egtA–ehaJ and ehaJ, respectively, were digested with XhoI (forward primer) and HindIII (reverse primer) and ligated to XhoI–HindIII digested plasmid pBAD/Myc-HisA to generate plasmids pOMS2 (contains egtA–ehaJ) and pOMS3 (contains ehaJ). In both constructs, expression of ehaJ is under control of the arabinose-inducible araBAD promoter (Guzman et al., 1995) and a stop codon is included so as to produce the recombinant protein without any tags introduced by the vector. The kanamycin cassette from pUC4K (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) was subsequently inserted into the HindIII site of pOMS2 to generate pOMS2-kan and enable its transformation into E. coli OS56. The pBAD/Myc-HisA vector was similarly manipulated to produce the negative control plasmid pBAD-kan.

Construction of an ehaJ mutant in EPEC strain MS455

The ehaJ gene was deleted from E. coli MS455 using a modification of the λRed recombinase gene replacement system (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000). The kanamycin cassette was amplified from pKD4 using primers 2571 (5′-ggcggatccgtgtaggctggagctgcttc) and 2572 (5′-ggcggatcccatatgaatatcctccttag), which include BamHI recognition sites. Flanking DNA consisting of approximately 500 bp up- and down-stream of ehaJ were amplified using primer pairs 2562 (5′-gccgctacagcaacgggtgga)/2575 (5′-ggcggatccgatgtggattccgcctgcgc) and 2576 (5′-ggcggatccacacactgaccatcaacggc)/2565 (5′-cgcatccagacactgccatct). The PCR products were digested with BamHI and the flanking regions ligated with T4 DNA ligase, PCR amplified, A-tailed and inserted in to the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega). The resulting plasmid was again digested with BamHI and the kanamycin cassette was ligated in between the two flanking regions. The ∼2.5 kb construct was then amplified using the outer most primers (2562 and 2565). This construct was used to transform MS455(pKD46) by electroporation; transformants were selected by growth on agar containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and screened by PCR using primers 2599 (5′-gagcagatattctgcgaata), 2600 (5′-ttgagctttcaggctcgcc), 2601 (5′-gctaccgagtgctgtgcatc), and 2602 (5′-tgtcggtgtcggcattgacg) in combination with primers specific for the kanamycin cassette (1287, 5′-ttgcacgcaggttctccg and 1288, 5′-acagctgcgcaaggaacg). The correct insertion of the kanamycin cassette was confirmed by sequencing using these same primers. This strain was referred to as MS455ehaJ.

antiserum production and immunoblotting

A 6× histidine-tagged truncated form of EhaJ was constructed. Primers 2377 (5′-tacttccaatccaatgcggaatccacatctgaggtgacg) and 2378 (5′-ttatccacttccaatgttaccaggacagtgaagtggtcag) were used to amplify the predicted passenger-encoding domain, which was then inserted into the pMCSG7 vector by ligation-independent cloning and maintained in E. coli DH5α. This plasmid was then transferred to E. coli BL21 for expression of the recombinant protein by induction with 1 mM IPTG and purification by Ni-NTA Superflow columns (Qiagen) under denaturing conditions. Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE analysis as previously described (Ulett et al., 2006). Polyclonal anti-EhaJ serum was raised in rabbits by the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Sciences (South Australia). For immunoblotting, cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride microporous membrane filters as described previously (Ulett et al., 2006). Serum raised against the passenger subunit of EhaJ was used as primary serum and the secondary antibody was alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G; 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-nitroblue tetraolium (BCIP/NBT) was used as the substrate in the detection process. Glycosylation of EhaJ was demonstrated by staining of SDS-PAGE separated proteins from whole cell lysates of MS427(pOMS2) with the Glycoprofile III stain (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Analysis of biofilm formation

Biofilm formation on polystyrene surfaces was assessed in 96-well microtiter plates (Iwaki) essentially as previously described (Kjaergaard et al., 2000). Briefly, MS427(pOMS2) or MS427(pOMS3) and MS427(pBAD) were grown for 24 h in glucose M9 minimal medium (containing 0.2% arabinose for induction of gene expression) at 37°C, washed to remove unbound cells and stained with crystal violet. Quantification of bound cells was assessed by adding acetone–ethanol (20:80) to dissolve the crystal violet, and the optical density was measured at 595 nm.

Flow chamber experiments were performed essentially as previously described (Allsopp et al., 2010) in M9 minimal media. Briefly, GFP-tagged strains OS56(pBAD-kan) and OS56(pOMS2-kan) were allowed to form biofilms on glass surfaces in a multi-channel flow system that permitted in situ monitoring of community structures. Flow cells were inoculated with OD600 standardized cultures grown overnight in M9 medium containing kanamycin. Biofilms were analyzed over 48 h, with confocal images captured at 16 and 48 h.

Microscopy and image analysis

An anti-EhaJ-specific serum was used for immunofluorescence microscopy as previously described (Wells et al., 2008). Briefly, overnight cultures of MS427(pBAD), MS427(pOMS2), and MS427(pOMS3) induced with 0.2% arabinose were fixed and incubated with primary rabbit polyclonal anti-EhaJ serum followed by incubation with a secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated to FITC. Microscopic observation of biofilms and image acquisition were performed on a scanning confocal laser microscope (LSM510 META, Zeiss) equipped with detectors and filters for monitoring of GFP. Vertical cross sections through the biofilms were visualized by using the Zeiss LSM image examiner. Images were further processed for display by using Photoshop software (Adobe, Mountain View, CA, USA). For analysis of the flow cell biofilms, z-stacks were analyzed using COMSTAT software program (Heydorn et al., 2000).

ECM protein binding assays

Bacterial binding to MaxGel Human ECM (Sigma-Aldrich) and extra cellular matrix (ECM) proteins was performed in a microtiter plate ELISA assay. Microtiter plates (MaxiSorp; Nunc) were coated overnight at 4°C with 2 μg of MaxGel Human ECM or individually with the following ECM proteins (final amount of 2 μg/well): collagen type I, type II, type III, type IV, and type V, fibronectin, fibrinogen, laminin, elastin, heparin sulfate, and BSA (Sigma-Aldrich). Wells were washed twice with TBS (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.4) and then blocked with TBS-2% skim milk for 1 h. After being washed with TBS, 200 μL of bacterial cell suspension (standardized to OD600 = 0.1) was added and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After being washed to remove non-adherent bacteria, adhered cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed, and incubated for 1 h with anti-E. coli serum (Meridian Life Sciences Inc., #B65001R) diluted 1:500 in 0.2% skim milk, 0.05% Tween-20 in TBS, washed and incubated for 1 h with a secondary anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; #A6154) diluted 1:1000 in 0.2% skim milk, 0.05% Tween-20 in TBS. After a final wash adhered bacteria were detected by adding 150 μL of 0.3 mg/ml ABTS [2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.1 M citric acid pH 4.3, activated with 1 μL/mL 30% hydrogen peroxide, and the absorbance was read at 405 nm. Mean absorbance readings were compared with negative control readings [MS427(pBAD)] using two-sample t-tests within the Minitab V14 software package (Coventry, UK). P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Prevalence of AT-encoding genes in EHEC and EPEC

The prevalence of selected AT-encoding genes from the AIDA-I and TAA groups was assessed by PCR screening of EHEC and EPEC strains from our laboratory collection. For this purpose, we employed primers designed to amplify a region within the conserved translocation-encoding domain of each gene. We found that a correct sized product was amplified from representative EHEC and EPEC strains for ehaA, ehaB, ehaC, ehaD, and the group 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 AT-encoding genes (Table 1). In contrast, no PCR product was obtained for the group 1 AT-encoding genes for any of the strains. Most of the EHEC and EPEC strains returned a positive result for ehaA, ehaB, and ehaC, indicating that these AT-encoding genes are highly prevalent. The group 2/3 PCR product was only amplified from EHEC strains (18%), while the group 4/5 PCR product was only amplified from EPEC strains (19%).

Table 1.

Prevalence of AT-encoding genes in EHEC and EPEC.

| Gene | EHEC (n = 44) | EPEC (n = 21a) | AT typeb |

|---|---|---|---|

| ehaA | 43 (97%) | 18 (86%) | AIDA-I |

| ehaB | 41 (93%) | 21 (100%) | AIDA-I |

| ehaC | 44 (100%) | 21 (100%) | AIDA-I |

| ehaD | 5 (11%) | 5 (24%) | AIDA-I |

| Group 1 | 0 | 0 | TAA |

| Group 2/3 | 8 (18%) | 0 | TAA |

| Group 4/5 | 0 | 4 (19%) | TAA |

| Group 6/7 | 44 (100%) | 21 (100%) | AIDA-I |

| ehaJ | 12 (27%) | 3 (14%) | AIDA-I |

aIncluding bioinformatic screening of EPEC strain E2348/69.

bAutotransporter type as indicated by Wells et al. (2010).

While the initial screening of the group 6/7 AT-encoding genes was based on a conserved set of primers for both groups, further screening with primers specific for the group 6 gene indicated that this gene is present in 12/44 (27%) of EHEC and 2/20 (10%) of EPEC strains. We focused the remainder of our study on this gene, and in accordance with the terminology adopted for other AT-encoding genes of EHEC (Wells et al., 2008), we have termed the group 6 AT-encoding gene ehaJ.

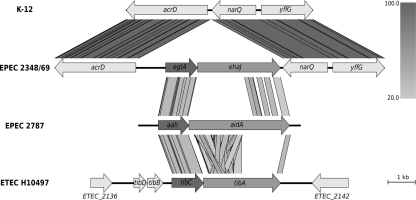

ehaJ lies adjacent to a putative glycosyltransferase gene

The EPEC strain 2348/69 is the only genome sequenced E. coli strain in the NCBI database that contains the ehaJ gene (locus tag E2348C_2704). Further investigation of the EPEC E2348/69 genome revealed the presence of a gene encoding a putative glycosyltransferase immediately upstream of ehaJ (locus tag E2348C_2705), which we have referred to as EhaJ glycosyltransferase or egtA (Figure 1). This tandem glycosyltransferase-AT gene arrangement is similar to that observed for the AidA and TibA AT proteins (Benz and Schmidt, 1989; Elsinghorst and Kopecko, 1992). EhaJ shares 26.1% amino acid identity with AidA and 22.7% amino acid identity with TibA. Both the AidA and the TibA AT genes are located immediately downstream of a glycosyltransferase encoding gene (Figure 1). The tib locus also contains two additional genes, tibD and tibB, which have been suggested to play a role in regulation (Lindenthal and Elsinghorst, 1999). The predicted product of the egtA gene shares 63.9% amino acid identity with the TibC glycosyltransferase from ETEC H10407 (Elsinghorst and Weitz, 1994) and 62.1% amino acid identity with the AIDA-associated Aah heptosyltransferase from EPEC 2787 (Benz and Schmidt, 1989, 1992).

Figure 1.

Genomic context of the group 6 autotransporter gene ehaJ and its associated glycosyltransferase gene egtA in EPEC 2348/69 genome (NC_011601) in comparison with K-12 strain MG1655 (NC_000913), EPEC 2787 (GU810159), and ETEC H10497 (FN649414). Whilst the arrangement of the glycosyltransferase upstream of the autotransporter gene is conserved, the genomic positions of these two genes are different in the four genomes. The figure was generated using Easyfig (http://easyfig.sourceforge.net/; Sullivan et al., 2011) with amino acid sequence comparison (tBLASTx). The level of amino acid identity is shown in the gradient scale.

The ehaJ gene encodes a protein that localizes to the cell surface

In order to determine if EhaJ is glycosylated and if glycosylation affects EhaJ function, we constructed two different plasmids. We selected one ehaJ-positive EPEC strain from our collection, MS455, and PCR amplified and cloned the egtA–ehaJ fragment as a transcriptional fusion downstream of the tightly regulated araBAD promoter in pBAD/Myc-HisA, resulting in plasmid pOMS2. Similarly, a plasmid containing the ehaJ gene alone was constructed by PCR amplification and cloning of the ehaJ gene from MS455 into pBAD/Myc-HisA, resulting in plasmid pOMS3. Unlike the AidA and Ag43 AT proteins, expression of EhaJ did not mediate cell aggregation following growth of these recombinant strains in LB or M9 broth. Furthermore, we found no evidence to indicate that the passenger domain of EhaJ could be released from the cell surface following brief heat treatment at 60°C.

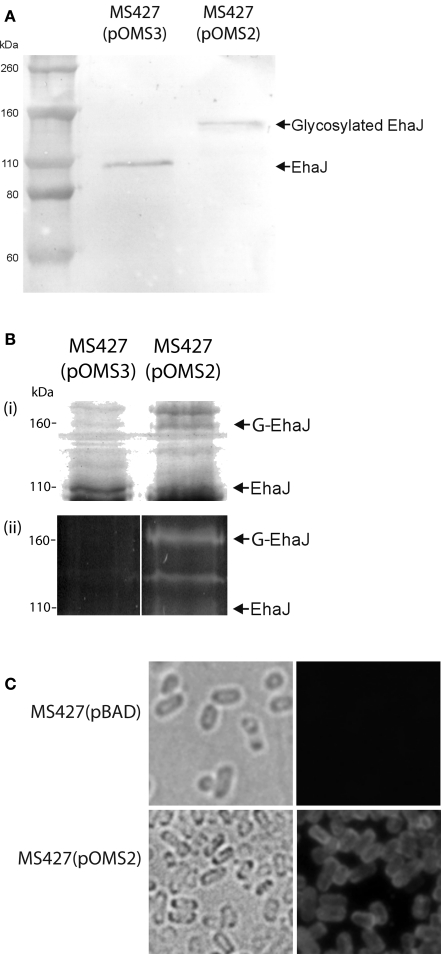

EhaJ is glycosylated in the presence of the egtA gene product

To demonstrate expression of the EhaJ protein, plasmids pOMS2 and pOMS3 were transformed into the previously described E. coli K-12 flu mutant strain MS427, respectively. E. coli MS427 is unable to mediate the classical cell aggregation and biofilm phenotypes associated with Ag43 expression (Reisner et al., 2003). EhaJ cell-surface expression was demonstrated by immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 2) using a rabbit polyclonal antiserum targeting a region in the predicted N-terminal passenger domain of EhaJ. Western blot analysis employing the same EhaJ-specific antiserum detected a 155-kDa protein in whole cell lysates prepared from E. coli MS427(pOMS2) following induction with arabinose (Figure 2). When the same analysis was performed on E. coli MS427(pOMS3), a smaller protein of approximately 110 kDa was detected using the EhaJ-specific serum. The difference in the size of EhaJ in the presence and absence of the egtA gene provides evidence to suggest that EhaJ is glycosylated. Glycosylation of EhaJ was demonstrated by staining of SDS-PAGE separated proteins from whole cell lysates of MS427(pOMS2) with the Glycoprofile III stain. Staining of the 155-kDa EhaJ protein was only observed in the presence of EgtA (Figure 2). A lower molecular weight band that also stained with Glycoprofile III was also visible on this gel (only in the presence of EgtA); we suggest that this band may represent a partially glycosylated version of EhaJ.

Figure 2.

(A) Western blotting with EhaJ-specific antiserum demonstrates the difference in size of EhaJ from MS427(pOMS2) and MS427(pOMS3). Molecular mass markers (M) are pre-stained Novex® Sharp Standard (Invitrogen). (B) SDS-PAGE analysis demonstrating (i) Coomassie blue staining and (ii) Glycoprofile III fluorescent staining of proteins prepared from whole cell lysates of MS427(pOMS2) and MS427(pOMS3). Staining of the 155-kDa EhaJ protein with Glycoprofile III was only observed in the presence of EgtA. A lower molecular weight band that also stained with Glycoprofile III and may represent a partially glycosylated form of EhaJ was also observed in MS427(pOMS2). Although this band is not visible on the western blot shown in (A), it was visible in other western blots that were allowed to develop for a longer time period. (C) Immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrating surface localization of EhaJ. Phase-contrast (left) and fluorescence (right) images of MS427(pBAD; top) and MS427(pOMS2; bottom). Strains were grown in the presence of 0.2% arabinose for all three panels. G-EhaJ indicates glycosylated EhaJ.

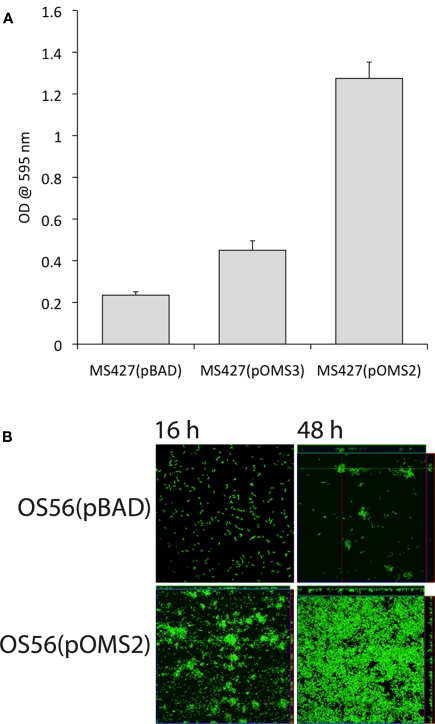

expression of glycosylated EhaJ mediates biofilm formation

To determine whether the EhaJ protein promotes biofilm formation, we examined the effect of EhaJ over-expression in E. coli MS427 in a static biofilm assay in a non-treated polystyrene microtiter plate model after growth in M9 minimal medium (Figure 3A). MS427(pOMS2), which produces glycosylated EhaJ, exhibited greatly enhanced biofilm production in comparison to both the negative control strain, MS427(pBAD) and the strain expressing EhaJ without the glycosyltransferase [MS427(pOMS3)]. The ability of glycosylated EhaJ to promote biofilm formation was further assessed by over-expression in E. coli OS56 (a GFP-tagged derivative of MS427) in dynamic conditions using the continuous flow chamber model, which permits monitoring of the bacterial distribution within an evolving biofilm at the single cell level due to the combination of GFP-tagged cells and scanning confocal laser microscopy. Glycosylated EhaJ [OS56(pOMS2)] promoted strong biofilm growth under these conditions and produced a structure with a depth of approximately 10 μm (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Glycosylated EhaJ [MS427(pOMS2)] mediates enhanced static biofilm formation in a microtiter plate assay at both 28°C and 37°C. Results are expressed as the average of six technical replicates within each plate; error bars indicate SD. These results are representative, confirmed by three independent experiments. (B) Glycosylated EhaJ mediates enhanced biofilm formation in a dynamic flow cell system at 28°C. Spatial distribution of dynamic biofilm formation by GFP-labeled E. coli strains OS56(pBAD-kan) and E. coli OS56(pOMS2-kan) was monitored by confocal scanning laser microscopy at 15 h (left) and 48 h (right) after inoculation. Shown are representative horizontal sections collected within each biofilm and vertical sections (to the right and below for each individual panel) representing the yz-plane and the xz-plane, respectively, at the positions indicated by the white lines.

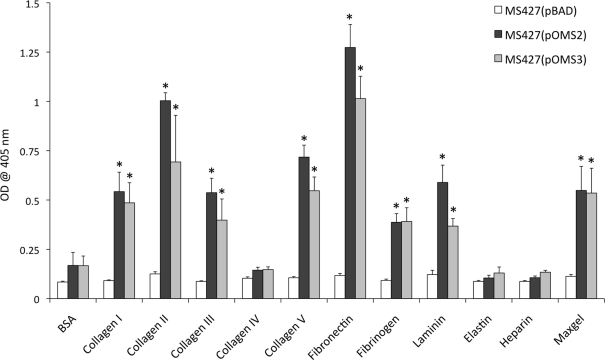

EhaJ mediates adherence to extracellular matrix proteins

To study the adhesive properties of EhaJ we examined its ability to mediate binding to various cellular and extracellular targets. Initially, we tested the ability of EhaJ to mediate adherence to HeLa and Caco2 cells, however no binding was observed for E. coli OS56(pOMS2-kan; data not shown). Next, we tested for the ability of EhaJ to mediate adherence to MaxGel, a commercially available mixture of ECM components including collagens, laminin, fibronectin, tenascin, elastin, a number of proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans. Both E. coli MS427(pOMS2) and E. coli MS427(pOMS3) adhered equally well in this assay (Figure 4), and thus we examined binding in more detail by testing a range of different ECM proteins. E. coli MS427(pOMS2) and E. coli MS427(pOMS3) adhered strongly to collagen I, collagen II, collagen III, collagen V, fibronectin, fibrinogen, and laminin (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

EhaJ mediates attachment to a range of ECM proteins in an ELISA-based binding assay. MS427 bound to MaxGel, collagen I, II, III and V, fibronectin, fibrinogen, and laminin when expressing ehaJ with or without co-expression of egtA [* indicates significant difference (P < 0.05) in comparison with BSA control]. EhaJ did not mediate adherence to collagen IV, elastin, heparin sulfate, or BSA.

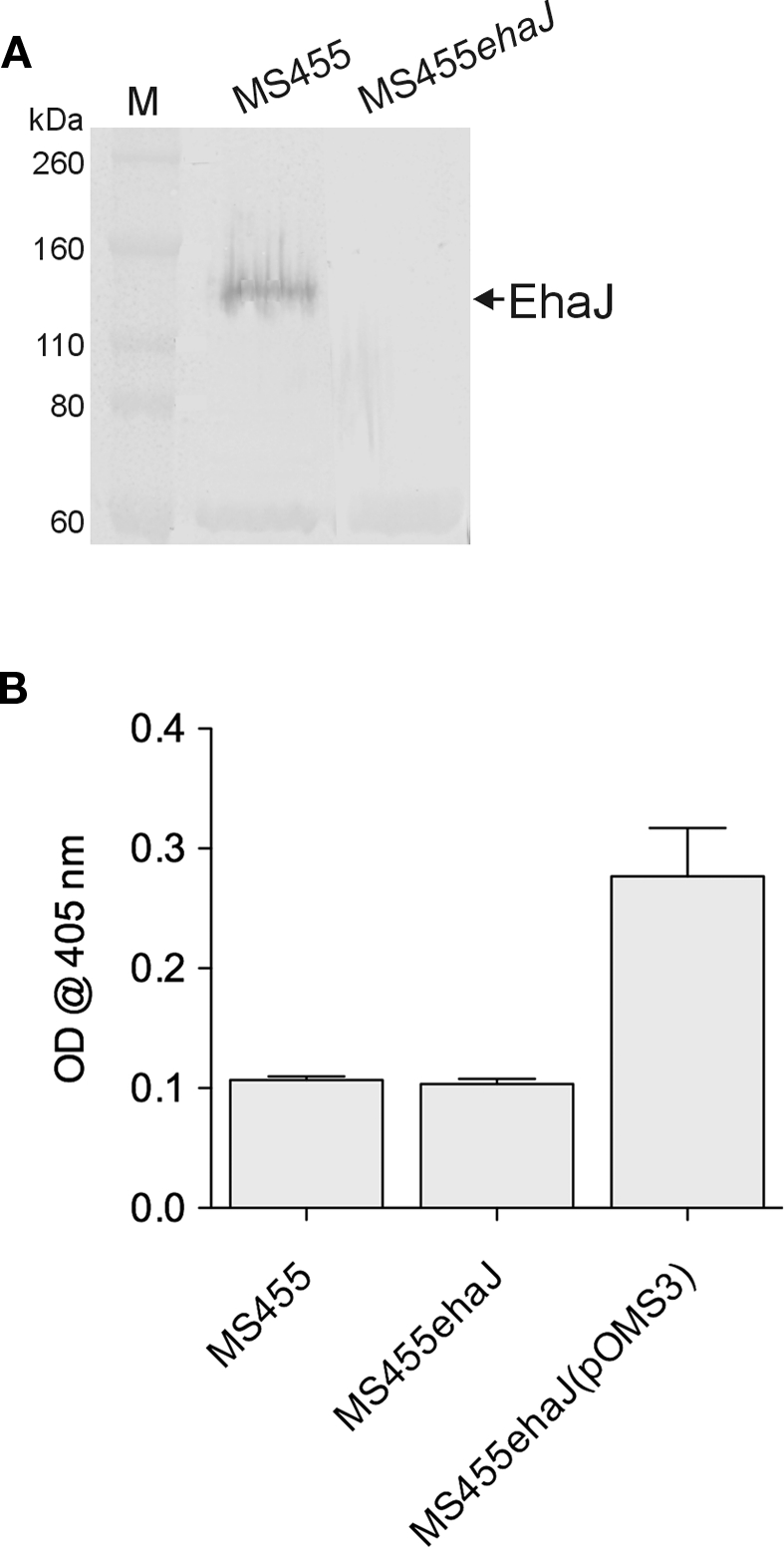

Construction and characterization of an ehaJ mutant

To determine whether EhaJ is expressed in wild-type EPEC MS455, we constructed an ehaJ deletion mutant employing λ-red mediated homologous recombination of linear DNA (referred to as MS455ehaJ). Examination of whole cell lysates prepared from MS455 and MS455ehaJ, following growth in LB broth, by SDS-PAGE and western blotting demonstrated a low level of expression of EhaJ in E. coli MS455 and an absence of EhaJ in MS455ehaJ (Figure 5). We then tested MS455 and MS455ehaJ for their ability to adhere to MaxGel. MS455 adhered poorly in this assay, and although MS455ehaJ adhered less well, the difference was not statistically significant. MS455ehaJ complemented with pOMS3 bound strongly to the MaxGel, consistent with results obtained when EhaJ was expressed under control of the araBAD promoter in the MS427 background (Figure 4 and data not shown). Similar results were also obtained with regards to biofilm formation in the microtiter plate assay (data not shown). Thus, while EhaJ is a newly identified AT protein expressed by E. coli MS455, further studies will be required to investigate the function of this protein in wild-type strains.

Figure 5.

(A) Western blotting with rabbit antiserum specific for the passenger domain of demonstrates expression of EhaJ in wild-type EPEC strain MS455 and loss of EhaJ in MS455ehaJ. Molecular mass (kDa) for the protein markers (M) [Novex Sharp Standards, Invitrogen] is shown on the right. (B) Wild-type strain MS455 did not bind strongly to the MaxGel protein mixture in an ECM binding assay and inactivation of EhaJ in strain MS455ehaJ did not reduce binding to ECM proteins in this assay (P = 0.55). However, over-expression of ehaJ (but not egtA) in MS455ehaJ(pOMS3) lead to a small but reproducible increase in binding to the MaxGel protein mixture (P = 0.008). An unpaired t-test was used for statistical comparisons using GraphPad Prism 5.

Discussion

Autotransporters are a diverse family of outer membrane proteins that have various virulence-associated functions, including in biofilm formation and adherence to mammalian cells. Our previous study of four AT proteins identified in E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933, termed EhaA, EhaB, EhaC, and EhaD, assessed the prevalence of these genes in STEC strains (Wells et al., 2008). In the present study, we have extended this analysis to include two strain libraries from our collection that have been confirmed by both serotyping and virulence gene analysis as EHEC or EPEC strains, for comparison of prevalence between these two pathotypes. The prevalence of the translocation (β) domain for each of these AT genes in the EHEC collection was found to be similar in this study to that found in our previous study (Wells et al., 2008) and also similar to the prevalence in the EPEC collection (Table 1).

Our recent bioinformatic approach to the identification and classification of AT proteins in E. coli revealed several predicted AT genes that did not group with those previously characterized and these were termed groups 1–7 (Wells et al., 2010). The present study also sought to assess the prevalence of these newly identified AT genes in our EHEC and EPEC libraries. Groups 1, 2, and 3, which were all closely grouped with the TAA clade, were not detected in our EPEC library in the current study. The group 1 gene was also not detected in the EHEC library and the group 2/3 screen only returned the correct PCR product in 18% of the EHEC strains. Each of these genes was only found in one publically available genome sequence (Wells et al., 2010); the group 1 gene was found in strain SMS 3–5, an environmental strain, and groups 2 and 3 were found in strain ED1a, originally isolated from a healthy adult. Thus it was not unexpected that these apparently rare AT genes would be absent from pathogenic strains. The group 4 gene was originally identified in strain UMN26, a uropathogenic strain, and the group 5 gene was identified in four strains, of differing pathotypes, including EPEC strain E2348/69. The current study indicated a modest prevalence of these genes (approximately 19%) in EPEC strains and an absence in EHEC strains. We note that the PCR-based approach we adopted does not distinguish between the presence of intact genes and pseudogenes. Future studies may address this issue and investigate the presence of these AT genes in different pathotypes of E. coli.

Screening for the translocation domain of the group 6 and 7 genes indicated that at least one of these genes is present in all of the strains tested in both the EHEC and EPEC libraries. However, specific screening for the group 6 gene, now termed ehaJ, found only a modest prevalence of this gene (15–27%), suggesting that the group 7 gene may be highly prevalent. However, BLASTn and BLASTp searches of E. coli genomes available through the NCBI database indicated that the group 7 gene is truncated to only the translocation domain, or parts of the translocation domain, in the majority of strains, explaining why this gene was not identified in more strains in the original study. The group 7 gene was found in only four strains previously, however the current searches identify the full gene in 11 E. coli strains and four Shigella flexneri strains. We chose to focus on the group 6 AT, which we have termed EhaJ, as analysis of the genomic context of the gene identified in EPEC strain E2348/69 (E2348C_2704) revealed the presence of a predicted glycosyltransferase immediately upstream (E2348C_2705), termed egtA. As shown in Figure 1, this is similar to the organization of the aah/aidA and tibC/tibA systems. Comparison of egtA with these other AT-associated glycosyltransferases revealed that egtA shares approximately 60% identity, with tibC and aah. Glycosylation of AIDA-I by the aidA-associated heptosyltransferase (AAH) is necessary for AIDA-I-mediated adherence to mammalian cells (Benz and Schmidt, 2001; Charbonneau et al., 2007). However, Charbonneau et al. (2007)also demonstrated that glycosylation is not necessary for the cell-binding domain to bind Hep-2 cells, but that glycosylation greatly enhances stability and protease-resistance of AIDA-I. They therefore suggest that glycosylation is needed for adherence only indirectly, in that it likely stabilizes the conformation of the cell-binding domain. TibA was the first glycosylated AT described in E. coli and a recent study has shown that its glycosyltransferase, TibC, is functionally interchangeable with AAH (Moormann et al., 2002). Both AIDA-I and TibA mediate bacterial aggregation and biofilm formation through self-association, but this function is independent of glycosylation (Sherlock et al., 2004, 2005).

Some AT proteins exhibit functional redundancy, such that deletion of individual AT genes often does not give rise to a measurable phenotype. As such, we chose to investigate the possible function of EhaJ, and the potential role of glycosylation by EgtA, in an E. coli MG1655flu strain, which is unable to mediate the classical cell aggregation and biofilm phenotypes associated with Ag43 expression (Reisner et al., 2003). Western blotting indicated that both genes were expressed in this background and that the EhaJ protein has a molecular mass of approximately 155 kDa on SDS-PAGE. However, the molecular mass of EhaJ was approximately 110 kDa when expressed in the absence of EgtA, suggesting that glycosylation of EhaJ is responsible for an approximately 45 kDa shift and that the genes encoding these two proteins are functional. Glycosylation of the 155-kDa protein was confirmed using the glycoprotein-specific Glycoprofile III stain. Additionally, immunofluorescence microscopy confirmed that EhaJ was expressed on the bacterial surface.

Several AT proteins mediate cell aggregation and biofilm formation independent of glycosylation, including Ag43, TibA, AidA (Sherlock et al., 2006), and the recently described EhaA (Wells et al., 2008). EhaJ differs from AIDA-I, TibC, and Ag43 in that the passenger domain does not disassociate from the translocation domain following brief heat treatment and induction of EhaJ expression in a K12flu background did not result in enhanced bacterial aggregation or biofilm formation in the absence of EgtA-mediated glycosylation. Most interestingly, EhaJ is able to promote biofilm formation when co-expressed with EgtA, demonstrating that this function is dependent upon glycosylation.

Further investigation of the function of EhaJ indicated that it mediates adherence to several ECM proteins. The apparent specificity of EhaJ binding to collagen I, collagen II, collagen III, collagen V, fibronectin, fibrinogen, and laminin is in line with studies on some other AT proteins. For example, EhaB mediates adherence to collagen I and laminin, but not collagen III, collagen IV or fibronectin (Wells et al., 2009), and Tsh (from avian pathogenic E. coli) mediates adherence to fibronectin and collagen IV, but not laminin (Kostakioti and Stathopoulos, 2004). Thus, it is clear that while many ATs bind a range of ECM proteins, the specificity of each AT differs, which likely reflects or influences the tissue tropism and pathogenicity of E. coli strains. We did not observe any significant difference in the adherence pattern of E. coli MS427(pOMS2) and E. coli MS427(pOMS3), suggesting that glycosylation of EhaJ does not affect adherence to these ECM proteins. However, it should be noted that small differences in adherence may have been masked by the over-expression of EhaJ, and thus differences may become apparent at lower EhaJ expression levels. Analysis of binding of the wild-type MS455 strain to ECM proteins indicated that this strain does not bind strongly to these proteins when grown in LB broth and deletion of ehaJ did not significantly reduce the level of binding. However, the strain was able to bind strongly when ehaJ was over-expressed under control of the araBAD promoter, suggesting that a low level of expression of ehaJ in the wild-type strain may account for this difference. Studies into the regulation of expression of ehaJ, and egtA, are therefore necessary to determine the growth conditions under which these genes are expressed to facilitate further functional studies.

Until relatively recently it was thought that only eukaryotic species glycosylate proteins, however many bacterial species are now known to possess N- and O-linked protein glycosylation systems (Nothaft and Szymanski, 2010). The targets of these systems tend to be cell-surface structures such as pili and flagella, in addition to AT proteins. EhaJ represents a new AT protein that mediates adherence to a set of specific extracellular matrix proteins and glycosylation of EhaJ appears to be necessary for its ability to promote biofilm formation. Future studies will explore the regulation of ehaJ and egtA to determine the growth conditions under which these genes are expressed and thus the potential significance of this glycosylated AT protein to virulence.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council to Mark A. Schembri (DP1097032) and the Queensland Government Smart Futures National and International Research Alliances Program (2008004328). Mark A. Schembri is supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellowship (FT100100662). We thank Robert Barlow (CSIRO), Helen Smith (QHFSS), and Steven Djordjevic (University of Technology, Sydney) for assistance in supply of strains.

References

- Allsopp L. P., Totsika M., Tree J. J., Ulett G. C., Mabbett A. N., Wells T. J., Kobe B., Beatson S. A., Schembri M. A. (2010). UpaH is a newly identified auto transporter protein that contributes to biofilm formation and bladder colonization by uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073. Infect. Immun. 78, 1659–1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardiau M., Szalo M., Mainil J. G. (2010). Initial adherence of EPEC, EHEC and VTEC to host cells. Vet. Res. 41, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz I., Schmidt M. A. (1989). Cloning and expression of an adhesin (AIDA-I) involved in diffuse adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 57, 1506–1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz I., Schmidt M. A. (1992). Isolation and serologic characterization of AIDA-I, the adhesin mediating the diffuse adherence phenotype of the diarrhea-associated Escherichia coli strain-2787 (O126-H27). Infect. Immun. 60, 13–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz I., Schmidt M. A. (2001). Glycosylation with heptose residues mediated by the aah gene product is essential for adherence of the AIDA-I adhesin. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 1403–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau M. E., Girard V., Nikolakakis A., Campos M., Berthiaume F., Dumas F., Lepine F., Mourez M. (2007). O-linked glycosylation ensures the normal conformation of the autotransporter adhesin involved in diffuse adherence. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8880–8889 10.1128/JB.00969-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. (2000). One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziva F., van Diemen P. M., Stevens M. P., Smith A. J., Wallis T. S. (2004). Identification of Escherichia coli O157:H7 genes influencing colonization of the bovine gastrointestinal tract using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microbiology 150, 3631–3645 10.1099/mic.0.27448-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsinghorst E. A., Kopecko D. J. (1992). Molecular cloning of epithelial cell invasion determinants from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 60, 2409–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsinghorst E. A., Weitz J. A. (1994). Epithelial cell invasion and adherence directed by the enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli tib locus is associated with a 104-kilodalton outer membrane protein. Infect. Immun. 62, 3463–3471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman L. M., Belin D., Carson M. J., Beckwith J. (1995). Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose pBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177, 4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyles C. L. (2007). Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: an overview. J. Anim. Sci. 85(Suppl. 13), E45–E62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson I. R., Navarro-Garcia F., Desvaux M., Fernandez R. C., Ala’Aldeen D. (2004). Type V protein secretion pathway: the autotransporter story. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 692–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson I. R., Navarro-Garcia F., Nataro J. P. (1998). The great escape: structure and function of the autotransporter proteins. Trends Microbiol. 6, 370–378 10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01318-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydorn A., Nielsen A. T., Hentzer M., Sternberg C., Givskov M., Ersboll B. K., Molin S. (2000). Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 146(Pt 10), 2395–2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose J., Jahnig F., Meyer T. F. (1995). Common structural features of IgA1 protease-like outer membrane protein autotransporters. Mol. Microbiol. 18, 378–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch H., Tarr P. I., Bielaszewska M. (2005). Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli in human medicine. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 295, 405–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaergaard K., Schembri M. A., Ramos C., Molin S., Klemm P. (2000). Antigen 43 facilitates formation of multispecies biofilms. Environ. Microbiol. 2, 695–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm P., Vejborg R. M., Sherlock O. (2006). Self-associating autotransporters, SAATs: functional and structural similarities. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296, 187–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostakioti M., Stathopoulos C. (2004). Functional analysis of the Tsh autotransporter from an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Infect. Immun. 72, 5548–5554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenthal C., Elsinghorst E. A. (1999). Identification of a glycoprotein produced by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 67, 4084–4091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low A. S., Holden N., Rosser T., Roe A. J., Constantinidou C., Hobman J. L., Smith D. G. E., Low J. C., Gally D. L. (2006). Analysis of fimbrial gene clusters and their expression in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 1033–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moormann C., Benz I., Schmidt M. A. (2002). Functional substitution of the TibC protein of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains for the autotransporter adhesin heptosyltransferase of the AIDA system. Infect. Immun. 70, 2264–2270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nataro J. P., Kaper J. B. (1998). Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11, 142–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls L., Grant T. H., Robins-Browne R. M. (2000). Identification of a novel genetic locus that is required for in vitro adhesion of a clinical isolate of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 275–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothaft H., Szymanski C. M. (2010). Protein glycosylation in bacteria: sweeter than ever. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 765–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton A. W., Srimanote P., Woodrow M. C., Paton J. C. (2001). Characterization of Saa, a novel autoagglutinating adhesin produced by locus of enterocyte effacement-negative Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli strains that are virulent for humans. Infect. Immun. 69, 6999–7009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner A., Haagensen J. A., Schembri M. A., Zechner E. L., Molin S. (2003). Development and maturation of Escherichia coli K-12 biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 933–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock O., Dobrindt U., Jensen J., Munk Vejborg R., Klemm P. (2006). Glycosylation of the self-recognizing Escherichia coli Ag43 autotransporter protein. J. Bacteriol. 188, 1798–1807 10.1128/JB.188.5.1798-1807.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock O., Schembri M. A., Reisner A., Klemm P. (2004). Novel roles for the AIDA adhesin from diarrheagenic Escherichia coli: cell aggregation and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 186, 8058–8065 10.1128/JB.186.23.8058-8065.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock O., Vejborg R. M., Klemm P. (2005). The TibA adhesin/invasin from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is self recognizing and induces bacterial aggregation and biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 73, 1954–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. J., Petty N. K., Beatson S. A. (2011). Easyfig: a genome comparison visualiser. Bioinformatics 28, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr P. I., Bilge S. S., Vary J. C., Jr., Jelacic S., Habeeb R. L., Ward T. R., Baylor M. R., Besser T. E. (2000). Iha: a novel Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence-conferring molecule encoded on a recently acquired chromosomal island of conserved structure. Infect. Immun. 68, 1400–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres A. G., Giron J. A., Perna N. T., Burland V., Blattner F. R., Avelino-Flores F., Kaper J. B. (2002). Identification and characterization of lpfABCC′DE, a fimbrial operon of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 70, 5416–5427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlich G. A., Keen J. E., Elder R. O. (2001). Mutations in the csgD promoter associated with variations in curli expression in certain strains of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2367–2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulett G. C., Webb R. I., Schembri M. A. (2006). Antigen-43-mediated autoaggregation impairs motility in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 152, 2101–2110 10.1099/mic.0.28607-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells T. J., McNeilly T. N., Totsika M., Mahajan A., Gally D. L., Schembri M. A. (2009). The Escherichia coli O157:H7 EhaB autotransporter protein binds to laminin and collagen I and induces a serum IgA response in O157:H7 challenged cattle. Environ. Microbiol. 31, 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells T. J., Sherlock O., Rivas L., Mahajan A., Beatson S. A., Torpdahl M., Webb R. I., Allsopp L. P., Gobius K. S., Gally D. L., Schembri M. A. (2008). EhaA is a novel autotransporter protein of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 that contributes to adhesion and biofilm formation. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 589–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells T. J., Totsika M., Schembri M. A. (2010). Autotransporters of Escherichia coli: a sequence-based characterization. Microbiology 156, 2459–2469 10.1099/mic.0.039024-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]