Domestic violence, now often referred to as intimate partner violence, is a common, costly, complex health problem. An estimated 5% to 14% of US women are currently living in abusive situations, and 22% report assault by a domestic partner during their lifetime.1 But addressing domestic violence in the health care setting is very complex—disclosure, seeking services, and recovery are all challenging.2 Despite recommendations from most professional organizations3 and clinical practice guidelines, screening for domestic violence in the health care setting remains infrequent.4

To address the complexities of domestic violence for patients as well as for health care providers, an innovative systems-model approach was developed and tested at a Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) facility in Richmond, California5 and is currently being implemented at all facilities in the KPNC Region.

… screening for domestic violence in the health care setting remains infrequent.4

Description of Program

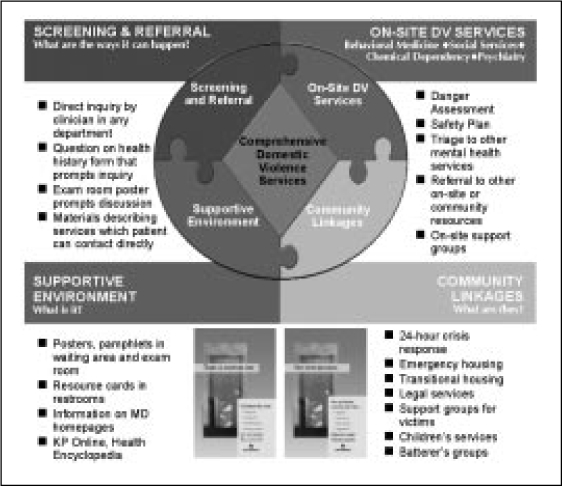

The systems model approach consists of four interrelated components: 1) a supportive environment, 2) screening and referral, 3) on-site domestic violence services, and 4) links with the community (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of systems-model approach used in a health care setting to diagnose and prevent domestic violence.

A supportive environment is established by using the physical environment of the facility to inform Health Plan members that domestic violence is an important issue and to encourage members to discuss domestic violence with their health care practitioner. Materials developed to convey this message include, among other items, a poster displaying a message of hope, a patient brochure, and resource information sheets designed to be posted in examination rooms and in restrooms (sometimes the only place where a victim has privacy).

Routine screening for domestic violence and referral to appropriate services are provided by clinicians during clinical encounters. During departmental meetings, focused staff training emphasizes simple, direct questions and is supplemented by referral-related feedback to clinicians and materials to facilitate their work (eg, toolkits, examination room posters, member information materials, and pocket reference cards outlining clinical practice guidelines).

Referral to on-site domestic violence services was designed to be simple and familiar and to ensure easy access to a mental health clinician and to information about domestic violence hotline numbers. Mental health clinicians (eg, LCSW, PhD, MFCC) receive training in domestic violence assessment and intervention and provide victims with a danger assessment, safety planning, information about resources in the community, and (in some facilities) an on-site support group.

Linkages to community agencies improve access to necessary services, such as a 24-hour crisis line, emergency housing, and legal assistance. In some communities, a crisis response team from the local advocacy agency is available to provide immediate assistance at the KP facility.

A Program That Works.

The Family Violence Prevention Program has helped KP to realize its mission to “improve the health of our members and the communities we serve” by developing strong ties to the community.

Examples of this community outreach:

Adoption of “There is another way …” poster in multiple communities throughout the United States.

Outreach to schools: “P.E.A.C.E. Signs” is performed by the KPNC Educational Theater Program at middle schools throughout Northern California.

Improvement of law enforcement response through collaborative training (Vallejo (CA) Police Department, 2002–2003).

Provision of resource information to members and the community via KPNC's Domestic Violence Web site: http://xnet.kp.org/domesticviolence/

Pilot Project

A yearlong pilot project was conducted in 1998 at a KP facility caring for 71,000 members (19,000 women aged 20–60 years) in Richmond, California.

The number of members identified and referred to mental health services for domestic violence increased 260%, from 51 referrals (during the preimplementation year) to 134 (during the first postimplementation year). Referrals increased across all departments, including medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, psychiatry, and emergency. A substantial number (18) were self-referrals. (Referrals have also continued to increase in each subsequent year.)6

A telephone survey adapted from a survey used in the KP Northwest Region7 was administered to a random sample of women Health Plan members seen for a regular checkup, either before implementation of the program (n = 190) or after its implementation (n = 201). Results of this survey showed statistically significant improvement in patient recall of being asked about domestic violence (p < 0.0001); improved patient awareness of domestic violence prevention information available at the KP facility (p < 0.0001); and satisfaction with KP efforts regarding domestic violence (p < 0.0001).8

On the basis of greatly improved screening and referral for domestic violence, the KPNC Family Violence Prevention Program was chosen as the gold winner of the American Association of Health Plans/Wyeth HERA award for 2003. This award is presented each year to health plans for exemplary programs that advance quality in women's and children's health.9 The KPNC Family Violence Prevention Program was also highlighted in a 2002 Institute of Medicine report as one of three health care institutions that successfully used systems change models for preventing intimate-partner violence.10

Expansion to all KPNC Facilities

Because of the success of the pilot program, the coordinated “systems-model” approach to family violence prevention is now being implemented at all KPNC facilities. To facilitate dissemination of the program throughout the region, resources were allocated for a clinical lead (a part-time physician), project manager, and assistant. This KP Family Violence Prevention Program provides assistance to local facility teams through regional workshops, site visits, phone consultation, a newsletter, and other resource materials (online and paper). To support implementation at the KP Regional level, the team also works on activities such as call center protocols, quality improvement measures, regulatory and compliance issues, and, more recently, KP HealthConnect. Online domestic violence materials for clinicians are available on the Clinical Library Web site (http://clinical-library.ca.kp.org) and, for Health Plan members, on the Health Encyclopedia Web site (http://members.kaiserpermanente.org/kpweb/healthency/entrypage.do).

In 2002, “Improving Domestic Violence Prevention” was selected by the KPNC Department of Quality and Utilization in collaboration with the KPNC Behavioral Health Quality Improvement Committee as a way of demonstrating implementation of a behavioral health guideline, a National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) standard. All three baseline requirements—an interdepartmental referral protocol, an MD/NP champion, and a multidisciplinary domestic violence prevention implementation team—have been met throughout the region. As a next step, the team developed two performance measures—percentage of target population identified and percentage of target population receiving appropriate referral. These measures are similar to those used to track improvement in conditions such as depression and are being used to monitor performance over time and between facilities.11

Analysis of Expansion

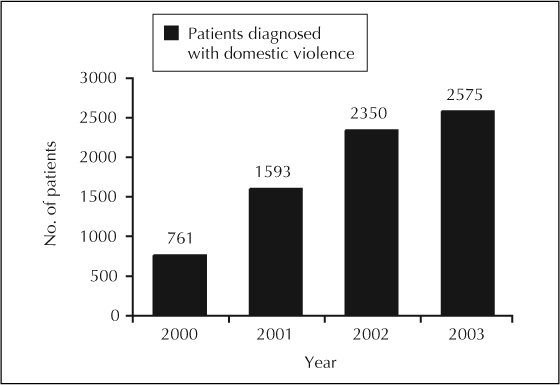

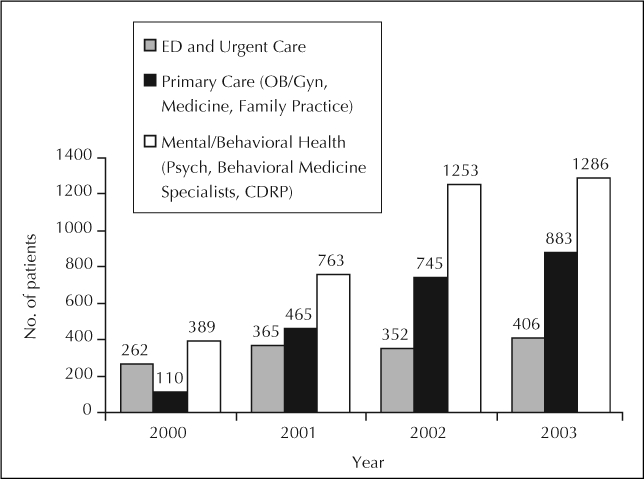

During the past four years, active dissemination of the domestic violence prevention program has been underway in KPNC, where data from an outpatient diagnosis database has shown a threefold increase in Health Plan members (both men and women) identified as currently affected by domestic violence (Figure 2). A notable trend is that identification is shifting to less acute settings, such as primary care (Figure 3): This trend suggests that these members are being identified before they present to the Emergency Department with a physical injury.

Figure 2.

Graph shows annual number of KP members in the Northern California Region diagnosed with domestic violence. As KP facilities in the Northern California Region implement the model, domestic violence is being diagnosed more frequently.

Figure 3.

Graph shows annual number of KP members in the Northern California Region diagnosed with domestic violence by department. Identification of domestic violence is shifting to less acute settings, such as Primary Care.

Although identification is improving dramatically, a substantial gap remains. Using a conservative prevalence rate of 4% for domestic violence in the previous 12 months,12–14 approximately 46,000 women members aged 18–60 years are currently affected by domestic violence. The data show that only about one in ten of these KPNC women members are identified and offered appropriate services. The opportunity for improvement is clear.

Identification of domestic violence is shifting to less acute settings, such as Primary Care.

KP is the first health plan to tackle this cross-cutting issue and to show substantial results from doing so.15 And KP is in a position to provide a model of excellence because of the sophisticated infrastructure, automated databases, and clinical training that underlie KP's integrated system of care. Improvement can be guided by providing meaningful performance data, an evidence-supported model of care, and implementation tools that support local teams. This robust combination allows successful adoption of the KPNC approach to domestic violence prevention throughout KP.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) leadership Robbie Pearl, MD; Don Dyson, MD; Sharon Levine, MD; and Timothy Batchelder, MD, for supporting the implementation of the systems model approach to domestic violence; Kaiser Foundation Hospital Administration, Zoe Sutton RN, MSN, PNP, for her substantial contribution as project manager for the Family Violence Prevention Program; Division of Research Enid Hunkeler, MA, and Nancy Gordon, PhD, for expertise in evaluation; and Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) Robert S Thompson, MD; Group Health Cooperative and Virginia Feldman, MD, for their guidance and encouragement.

References

- Wilt S, Olson S. Prevalence of domestic violence in the US. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1996 May Jul;51(3):77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbert B, Abercrombie P, Caspers N, Love C, Bronstone A. How health care providers help battered women: the survivor' s perspective. Women Health. 1999;29(3):115–35. doi: 10.1300/J013v29n03_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Family Violence Prevention Fund. National consensus guidelines on identifying and responding to domestic violence victimization in health care settings [monograph on the Internet] San Francisco (CA): The Family Violence Prevention Fund; 2004. [cited 2004 Dec 6]. Available from: http://endabuse.org/programs/healthcare/files/Consensus.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, McLoughlin E, Grumbach K. Screening and intervention for intimate partner abuse: practices and attitudes of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1999 Aug 4;282(5):468–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.5.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salber PR, McCaw B. Barriers to screening for intimate partner violence: time to reframe the question. Am J Prev Med. 2000 Nov;19(4):276–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaw B, Bauer HM, Berman WH, Mooney L, Holmberg M, Hunkeler E. Women referred for on-site domestic violence services in a managed care organization. Women Health. 2002;35(2–3):23–40. doi: 10.1300/J013v35n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shye D, Feldman V, Hokanson CS, Mullooly JP. Secondary prevention of domestic violence in HMO primary care: evaluation of alternative implementation strategies. Am J Manag Care. 2004 Oct;10(10):706–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaw B, Berman H, Syme SL, Hunkeler EF. Beyond screening for domestic violence: a systems model approach in a managed care setting. Am J Prev Med. 2001 Oct;21(3):170–6. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso B. Domestic violence prevention program receives national award. Perm J. 2003 Fall;7(4):69. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn F, Salmon ME, Stobo JD, editors. Committee on the Training Needs of Health Professionals to Respond to Family Violence. Confronting chronic neglect: the education and training of health professionals on family violence [monograph on the Internet] Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2002. [cited 2004 Nov 10]. Available from: www.nap.edu/openbook/0309074312/html/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Another way to save a life: American Association of Health Plans presents Gold Award to a KP program that prevents domestic abuse. Quality Notes [serial on the Internet] 2003 Fall;15(3):6–7. [cited 2004 Nov 10] Available from: http://kpnet.kp.org/qrrm/publications/qualnotes/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Cross M. Why looking for victims of domestic violence makes sense. Managed Care [serial on the Internet] 2003 May;12(5):27–30. [cited 2004 Nov 10] Available from: www.managedcaremag.com/archives/0305/0305.violence.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. The “battering syndrome” : prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Nov 15;123(10):737–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Health Services, Maternal and Child Health Branch, Domestic Violence Section. p. 1. Adult female victims of intimate partner physical domestic violence (IPP-DV), California, 1998. Data Points [serial on the Internet]. 2001 Spring [cited 2004 Dec 6];2(18):[about. p. ]. Available from: www.dhs.ca.gov/director/owh/1998%20datapoints.htm.

- Gordon NP. Characteristics of adult health plan members in the Northern California Region membership, as estimated from the 2002 Member health survey [monograph on the Internet] Oakland (CA): Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program, Division of Research; 2004. [cited 2004 Dec 6]. Available from: http://dorsunfire.kaiser.org/dor/mhsnet/pdf_02/mhs02reg.pdf (available only to internal users) [Google Scholar]