Abstract

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP; ABCG2), a clinical marker for identifying the side population (SP) cancer stem cell subgroup, affects intestinal absorption, brain penetration, hepatobiliary excretion, and multidrug resistance of many anti-cancer drugs. Nutlin-3a is currently under pre-clinical investigation in a variety of solid tumor and leukemia models as a p53 reactivation agent, and has been recently demonstrated to also have p53 independent actions in cancer cells. In the present study, we first report that nutlin-3a can inhibit the efflux function of BCRP. We observed that although the nutlin-3a IC50 did not differ between BCRP over-expressing and vector control cells, nutlin-3a treatment significantly potentiated the cells to treatment with the BCRP substrate mitoxantrone. Combination index calculations suggested synergism between nutlin-3a and mitoxantrone in cell lines over-expressing BCRP. Upon further investigation, it was confirmed that nutlin-3a increased the intracellular accumulation of BCRP substrates such as mitoxantrone and Hoechst 33342 in cells expressing functional BCRP without altering the expression level or localization of BCRP. Interestingly, nutlin-3b, considered virtually “inactive” in disrupting the MDM2/p53 interaction, reversed Hoechst 33342 efflux with the same potency as nutlin-3a. Intracellular accumulation and bi-directional transport studies using MDCKII cells suggested that nutlin-3a is not a substrate of BCRP. Additionally, an ATPase assay using Sf9 insect cell membranes over-expressing wild-type BCRP indicated that nutlin-3a inhibits BCRP ATPase activity in a dose-dependent fashion. In conclusion, our studies demonstrate that nutlin-3a inhibits BCRP efflux function, which consequently reverses BCRP-related drug resistance.

Keywords: Nutlin-3a, Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), ABC transporter, Multi- drug resistance

1. Introduction

Pre-clinical investigations of the utility of nutlin-3 treatment of cancer cells have focused primarily on the consequences of p53 reactivation in cells due to disruption of the MDM2/p53 interaction. Nutlin-3 is a racemic mixture of nutlin-3a (active enantiomer) and nutlin-3b (inactive enantiomer) with nutlin-3a having 150-fold more affinity to MDM2 [1]. Indeed, single agent nutlin-3 treatment has shown anti-cancer efficacy in xenograft models of solid tumors, including osteosarcoma, prostate cancer, KSHV lymphomas, retinoblastoma, and neuroblastoma [1-5]. Recently, other effects of nutlin-3 treatment have been reported, including anti-angiogenic effects [6-8] and radiosensitization of cancer cells under low oxygen conditions [9]. Furthermore, nutlin-3 has been reported to sensitize cancer cells to co-treatment with selected anti-cancer drugs, independent of p53 status, by enhancing the ability of anticancer drugs to activate apoptosis [10], and also by reversing P-glycoprotein (P-gp; ABCB1) mediated multi-drug resistance (MDR) [11]. Understanding the mechanism behind this nutlin-3 sensitization of resistant cancer cells would significantly enhance the use of nutlin-3 in combination with other anti-cancer drugs in a broad range of tumor types.

Drug-resistance is a major obstacle in the treatment of cancer, and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters play an integral role in the development of multi-drug resistance [12]. ABC transporters utilize the energy of ATP hydrolysis to pump anti-cancer agents out of the cell, thus reducing the intracellular drug concentration. Recently, Michaelis et al. observed that nutlin-3 can interfere with the function of the ABC transporters P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1; ABCC1) [11]. Nutlin-3 treatment reversed drug resistance in neuroblastoma and rhabdomyosarcoma cells over-expressing these transporters in vitro when combined with cytotoxic drugs that are P-gp and MRP1 substrates. These data suggest that nutlin-3 functionally inhibits the action of drug efflux proteins, thereby sensitizing cells to treatment with cytotoxic agents that are substrates of these efflux proteins.

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP; ABCG2) belongs to the ABC transporter family. Although it is possible that nutlin-3a may modulate the activity of BCRP, so far, the effect of nutlin-3a on BCRP has not been reported. The present study investigates whether nutlin-3a inhibits BCRP, thus sensitizing cells to enhanced killing by anti-cancer drugs that are BCRP substrates. Using MTS assays, we determined that nutlin-3a reverses resistance to the BCRP substrate mitoxantrone. Combination index calculations indicated synergism when nutlin-3a was used in combination with the anticancer agent mitoxantrone, a BCRP substrate, in osteosarcoma cells over-expressing BCRP. Based on these observations, we performed a series of studies to comprehensively investigate the effect of nutlin-3a treatment on BCRP expression and function. Our studies strongly suggest that nutlin-3a inhibits BCRP efflux and can reverse BCRP-related drug resistance, but is not a BCRP substrate.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Nutlin-3a and nutlin-3b were synthesized in the Department of Chemical Biology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN and were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (ATCC, Manassas, VA) to a final concentration of 30 mM. The chemical structure of nutlin-3 has been published previously [1]. Hoechst 33342 and G-418 (Geneticin®) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Mitoxantrone and Ko143 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Fumitremorgin C (FTC) was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA).

2.2. Cell culture

Saos-2 (human osteosarcoma) cells stably transfected with human wild-type (Arg482) BCRP or control vector pcDNA3.1 were generously donated by Dr. John Schuetz (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN) [13, 14]. MDCK II- pCDNA3.1 and MDCK II-BCRP cells were generously donated by Dr. Mark Leggas (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY). Cells were cultured in complete Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) media(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1% Glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and maintained with G418 (0.5 mg/ml) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were cultured in G418-free complete media at the time of seeding for individual experiments. Hank’s balance salt solution (HBSS) and HEPES buffer were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

2.3.Cell viability assay (MTS)

Cells were seeded in 100 μl phenol red-free medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 96-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of nutlin-3a alone or increasing concentrations of mitroxantrone in combination with 0 μM, 20 μM or 50 μM nutlin-3a for 24 hours. Cell viabilities were tested by the CellTiter 96® AQueous MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's instructions. IC50 values were calculated using ADAPT 5 (Biomedical Simulations Resources, Los Angeles, CA) [15] .

2.4.Median effect analysis

To characterize the interaction between mitroxantrone and nutlin-3a in Saos-2-BCRP and Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 cells, data were analyzed using the median effect method developed by Chou and Talalay [16]. The combination index (CI) values at non-fixed nutlin-3a/mitoxantrone concentration ratios were calculated using the commercially available software Calcusyn 2.1 (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom). CI values <1.0 indicate synergism, CI values =1.0 indicate additive effect and CI values >1.0 indicate antagonism [16].

2.5. Intracellular accumulation and efflux of mitoxantrone by confocal imaging

Vector control and BCRP expressing Saos-2 cells were seeded on 35 mm glass bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA) and allowed to attach for 36 hours. Cells were pre-incubated with nutlin-3a for 15 minutes in DMEM+ (DMEM media with 2% FBS, 1 mM HEPES buffer) at 37°C. Mitoxantrone (1 μM) was added and cultures were incubated for an additional 1 hour. Cells were washed with ice cold HBSS+ (HBSS with 2% FBS, 1 mM HEPES buffer) containing nutlin-3a and intracellular accumulation was measured using confocal imaging. An Eclipse C1si confocal, configured on an Eclispe TE2000 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) with a Plan Fluor 40 × NA 1.3 lens was used. Excitation was from a 642 nm diode laser, and the emission was collected through a 675/50 nm bandpass filter.

2.6. Hoechst 33342 dye accumulation and efflux studies by flow cytometry

Hoechst 33342 dye was used as a BCRP substrate. Vector control and BCRP over-expressing Saos-2 and MDCKII cells were cultured to 60–70% confluence. Single cell suspensions were pre-incubated in DMEM + with nutlin-3a, nutlin-3b or FTC at varying concentrations for 15 minutes at 37°C. Hoechst 33342 dye was then added to a final concentration of 5 μg/ml and cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in ice cold HBSS+ containing nutlin-3a, nutlin-3b or FTC. Intracellular Hoechst 33342 fluorescence signals were detected by a 440/40 nm band pass filter with UV laser excitation and the data were collected and analyzed using a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA). Data were processed as previously described [14]. Propidium iodide (PI) (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) was added as a marker to label the non-viable cells. Only events from viable cells were used for data analysis.

2.7.Intracellular accumulation and efflux of Hoechst 33342 by widefield imaging

Vector control and BCRP expressing Saos-2 cells were seeded on 35 mm glass bottom dishes and allowed to attach for 36 hours. Cells were pre-incubated with nutlin-3a or nutlin-3b in DMEM+ for 15 minutes at 37°C. Hoechst 33342 (1 μg/ml) was added and cultures were incubated for an additional 1 hour. Cells were washed with ice cold HBSS+ containing nutlin-3a or nutlin-3b and intracellular accumulation was measured using widefield fluorescence imaging. Hoechst 33342 imaging was performed on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 microscope with a Plan Fluor 40 × NA 0.6 lens and a standard DAPI filter set.

2.8.Western blots

Total cellular protein was extracted from cell pellets and protein concentrations were determined by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Proteins were resolved by SDS PAGE [4-12% gradient Bis/Tris NuPage gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)] with MOPS SDS running buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) before transferring onto InvitrolonTM PVDF membranes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). BCRP was detected using the rat monoclonal BXP-53 (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA). P-gp was detected using the mouse monoclonal antibody clone C-219 (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA). Beta-actin (AC-15, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as the loading control.

2.9.Flow cytometry for BCRP

PE conjugated mouse anti-BCRP (MAB4155P) (Millipore, Billerica, MA) antibody was used to detect protein expression by flow cytometry. Cells were treated with 50 μM nutlin-3a for 1 hour, harvested, and then 1.0 × 106 cells were resuspended in 100 μL BD Fc BlockTM (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and incubated on ice for 30 minutes. Cells were washed once and then stained with the primary antibody (anti-BCRP 10 μg/ mL) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Cells were again washed and resuspended in a final volume of 0.5 ml. Cells were counterstained with 4'-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and analyzed using a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA).

2.10. BCRP localization

Localization of BCRP was evaluated using confocal imaging analysis. Cells were grown on 35 mm glass bottom dishes and treated with 50 μM nutlin-3a for 90 minutes. After incubation, cells were washed with HBSS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) for 15 minutes at room temperature. After 3 HBSS washes, cells were permeabilized using 0.2 % Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted in HBSS for 5 minutes then washed in HBSS. After 3 HBSS washes, Image-iT FX signal enhancer solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was applied and the dishes were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. After 3 additional HBSS washes, mouse monoclonal antibody against BCRP (BXP-21, Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA) (1:1000 diluted in HBSS + 2% bovine serum albumin) was added and cells were incubated for an additional 60 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then stained with Alexa Fluor® 555 goat anti-mouse IgG secondary detection conjugate (1:500) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at room temperature for 90 minutes. Finally, ProLong® Gold-DAPI anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added and wells were cover-slipped. BCRP localization was assessed using confocal imaging. A Nikon Eclipse C1si confocal configured on an Eclipse TE2000 microscope with a Plan Fluor 40 × NA 1.3 lens was used. Excitation was from a 561 nm diode laser and emission was collected through a 605/75 nm bandpass filter.

2.11. Intracellular accumulation of nutlin-3a

MDCKII-pcDNA3.1 and MDCKII-BCRP cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 0.5 × 105 cells/well in 2 mL of complete DMEM without G418. When cells were 80~90% confluent, nutlin-3a was added at increasing final concentrations of 0, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 μM. Cells were incubated at 37° C for 1 hour. Cells were then washed with ice cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) twice, and scraped off in 1ml ice cold homogenization buffer (5 mM HCOONH4, pH 7.0). Cell pellets were then lysed on ice by sonicating for approximately 10 sec/ well twice with a 15 sec interval using a 4710 series ultrasonic homogenizer (Cole-Parmer, Chicago, IL, USA). Intracellular nutlin-3a concentrations were measured using the LC-MS/MS method published previously [17]. Final intracellular nutlin-3a concentrations were normalized to total protein content as measured by BCA assay.

2.12. Bi-directional transport across MDCKII monolayer cells

MDCKII-pCDNA3.1 and MDCKII-BCRP cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells per well in 0.4 μm, 12 mm Transwell® permeable inserts (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY). Transport assays were performed when cells reached consistent trans-epithelial electrical resistance [18] values (between 200–300 μΩ cm2), indicating that the cells had formed a confluent polarized monolayer. Prior to transport assays (30 minutes), the medium in the donor and receiver chambers was removed and replaced with transport buffer (HBSS/25 mM HEPES). Buffer containing nutlin-3a was added to either the apical or the basolateral side of the monolayer with or without the BCRP-specific inhibitor Ko143. Samples were removed for the determination of initial nutlin-3a concentrations, and then at 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes. 50 μl aliquots were removed from the either the basolateral or apical compartments. The volume removed was replaced immediately with fresh transport buffer. Nutlin-3a samples were prepared and analyzed using LC-MS/MS method as described above.

The apparent permeability (Papp) is calculated using Equation 1 [18]:

| Equation 1 |

Where Vr is the volume of buffer in the receiver chamber; C0 is the initial drug concentration in the donor chamber; S is the surface area of monolayer; dC/dt is the linear slope of drug concentration over time.

The efflux ratio (RE) is calculated using Equation 2:

| Equation 2 |

Where Papp,B-A is the apparent permeability of drug transport from basolateral to apical side and Papp,A-B is the apparent permeability of drug transport from apical to basolateral side. The final efflux ratio (R) is calculated using Equation 3:

| Equation 3 |

2.13. ATPase assay

BCRP ATPase activity was determined using SB BCRP HAM PREDEASY ATPase kit and SB defBCRP HAM PREDEASY Ctrl kit following the manufacturer's instructions (XenoTech, Lenexa, KA). The assay contains two different tests that are performed simultaneously on the same plate. In the activation test, BCRP substrates stimulate baseline vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity. In the inhibition test, inhibitors or slowly transported compounds may inhibit the maximal vanadate sensitive ATPase activity. Nutlin-3a was tested in both the activation and inhibition reactions at increasing concentrations (0.14, 0.41, 1.23, 3.70, 11.11, 33.33, 100, and 150 μmol/L) for 10 minutes following the manufacturer's instructions. The assay was performed in triplicate.

2.14. Statistical analysis

All data expressed as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise indicated. Data were analyzed for statistical significance using Student’s t test. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Linear and nonlinear regressions were performed using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

3. Results

3.1. Nutlin-3a sensitizes BCRP expressing cells to mitoxantrone treatment

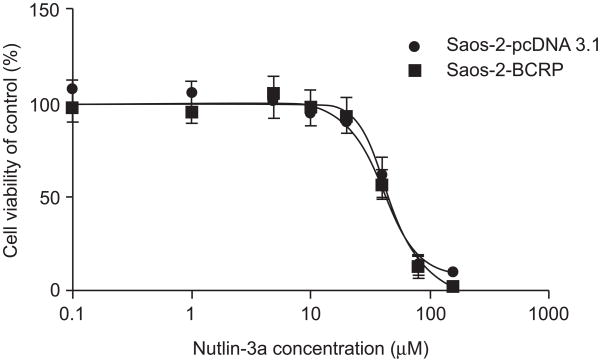

Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were incubated with nutlin-3a alone or in combination with the anti-cancer agent mitoxantrone, a BCRP substrate. IC50 values were determined by MTS assay. BCRP over-expression did not confer resistance to nutlin-3a as a single agent. The IC50 value of nutlin-3a was 45.8 (±2.6) μM for Saos-2-BCRP and 43.5 (±3.0) μM for Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 (p>0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

BCRP expression does not confer resistance to nutlin-3a treatment. Saos-2-BCRP and Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of nutlin-3a (0.1-150 μM) for 24 hours. Cell viabilities were tested by MTS assay in triplicate. IC50 values were calculated using ADAPT 5. Values are presented as mean ± SD. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

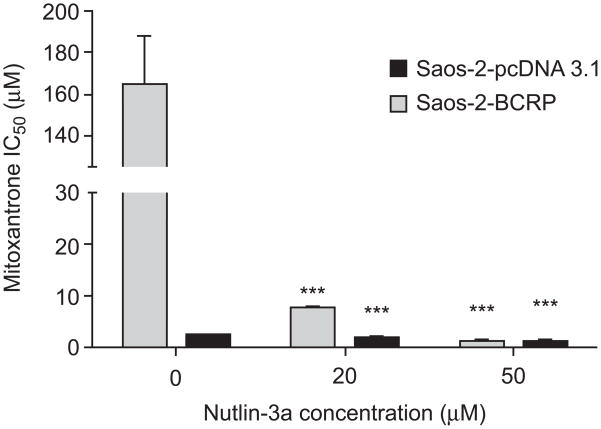

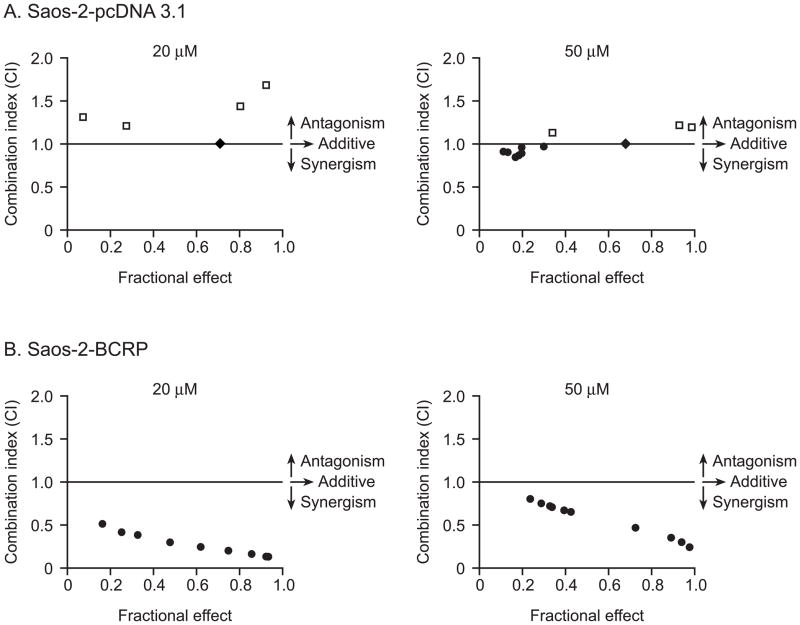

BCRP expression did confer resistance to mitoxantrone in the Saos-2 cell lines. The Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 cells exhibited sensitivity to mitoxantrone with an IC50 of 2.0 (±0.1) μM while the BCRP over-expressing Saos-2 cells had a markedly increased mitoxantrone IC50 of 165.8 (±21.9) μM (P<0.001) (Figure 2). To determine the effect of nutlin-3a on potentially reversing this mitoxantrone resistance, Saos-2-BCRP cells were co-incubated with 20 μM or 50 μM nutlin-3a and increasing concentrations of mitoxantrone (0.01-300 μM) for 24 hours. A dramatic reduction in the mitoxantrone IC50 from 165.8 (±21.9) μM to 7.6 (±0.5) μM (21.8-fold, p<0.001) and 1.0 (± 0.07) μM (165.8-fold, p<0.001) was observed in the Saos-2-BCRP cells after treatment with 20 and 50 μM nutlin-3a, respectively (Figure 2). In Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 cells, only a moderate reduction of mitoxantrone IC50 was observed, from 2.0 (±0.01) μM to 1.4 (±0.1) μM (1.4-fold, p<0.001) and 0.6 (±0.4) μM (3.3-fold, p<0.001) (Figure 2). Using combination index analysis, we evaluated whether the combination of nutlin-3a and mitoxantrone was synergistic. Combination index (CI) values around 1 indicate that two drugs have an additive effect. A CI <1 indicates synergy, and a CI>1 indicates antagonism [16]. The fractional effect is the ratio of the effect (growth inhibition) caused by the two compounds in combination to that of one of the compounds alone. A fractional effect value of 0 indicates no inhibition and fractional effect value of 1 indicates 100% inhibition of cell viability. In contrast to Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 cells where synergism, additivity, and antagonism can be observed on different nutlin-3a: mitoxantrone ratios (Figure 3A), moderate (++) to strong (++++) synergism [16] was observed in Saos-2-BCRP cells with combination index (CI) values between 0.132 and 0.798 at all nutlin-3a: mitoxantrone ratios tested (Figure 3B). These results indicate that the synergistic effect observed in Saos-2-BCRP cells induced by the nutlin-3a/mitoxantrone combination is dependent on the presence of BCRP.

Figure 2.

Co-treatment of cells with nutlin-3a and mitoxantrone strongly reverses BCRP mediated drug resistance to mitoxantrone. Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were treated with increasing concentrations of mitoxantrone (0.01-300 μM) in combination with 20 and 50 μM nutlin-3a for 24 hours as described in the methods. Cell viabilities were determined by MTS assay in triplicate. ADAPT 5 was used to calculate IC50. Values are presented as mean ± SD. *** P<0.001. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Synergistic effects of nutlin-3a in combination with mitoxantrone. The combination index (CI) values at non-fixed nutlin-3a/mitoxantrone concentration ratios were calculated using commercially available software Calcusyn 2.1. ● CI values <1.0 indicate synergism, ◆ CI values = 1.0 indicate additive effect and □ CI values >1.0 indicate antagonism. Fractional effect (Fa) is defined as the fraction of cells affected by nutlin-3a and mitoxantrone combination. A fractional effect value of 0 indicates no inhibition and a fractional effect value of 1 indicates 100% inhibition of cell viability. A, for Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 cells, at 20 μM nutlin-3a, additive effect and antagonism were observed. At 50 μM nutlin-3a, when nutlin-3a: mitoxantrone ratios were >100:1, both additive and synergistic effects were observed; when nutlin-3a: mitoxantrone ratios were <100:1, antagonism was observed. B, for Saos-2-BCRP cells, moderate (++) to strong (++++) synergism was observed at all ratios tested. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

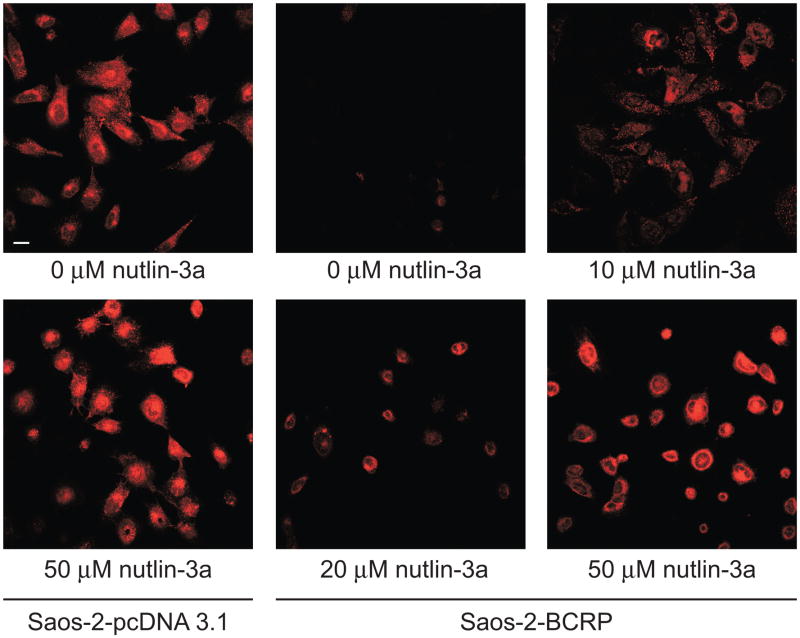

3.2. Nutlin-3a inhibits BCRP-mediated transport of mitoxantrone

To determine whether the observed reduction in the mitoxantrone IC50 of the Saos-2-BCRP cells co-treated with nutlin-3a was due to increased exposure to mitoxantrone, intracellular accumulation of mitoxantrone was measured by confocal imaging. Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were co-incubated with 1 μM mitoxantrone and increasing concentrations of nutlin-3a (0 to 50 μM) for 1 hour. In the absence of nutlin-3a, little mitoxantrone accumulation was observed in Saos-2-BCRP cells (Figure 4), indicating active efflux by BCRP, whereas under the same conditions, mitoxantrone was retained in the Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 cells. Treatment with nutlin-3a resulted in a dose-dependent increase in the intracellular mitoxantrone accumulation in the Saos-2-BCRP cells, suggesting a decrease in BCRP efflux function.

Figure 4.

Nutlin-3 treatment strongly increases the intracellular accumulation of mitoxantrone in Saos-2-BCRP cell lines. Confocal imaging of mitoxantrone (red) in Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells in the presence increasing concentrations of nutlin-3a for 60 minutes suggested dose dependent restoration of intracellular mitoxantrone accumulation. Scale bar, 30 μm. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

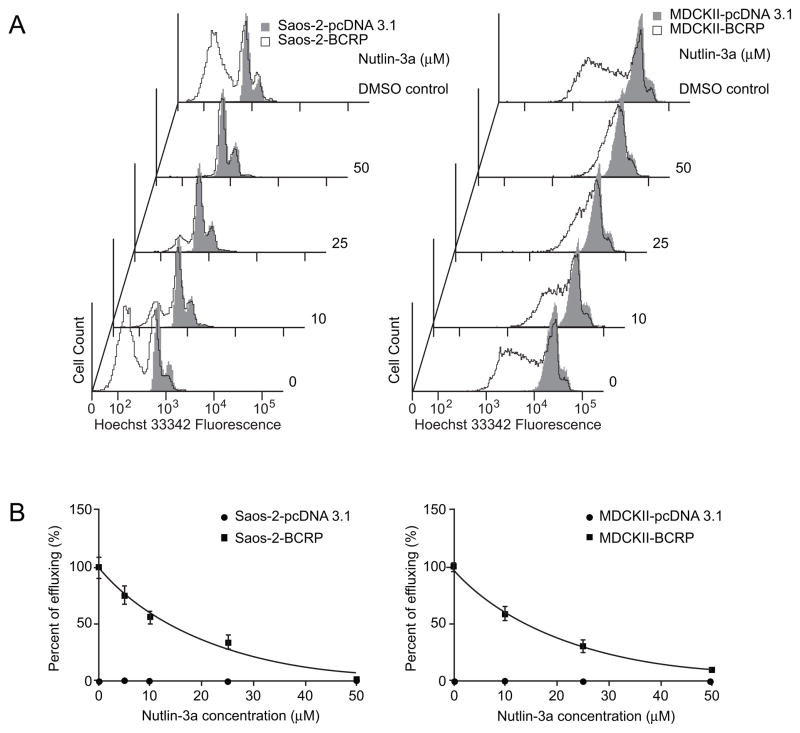

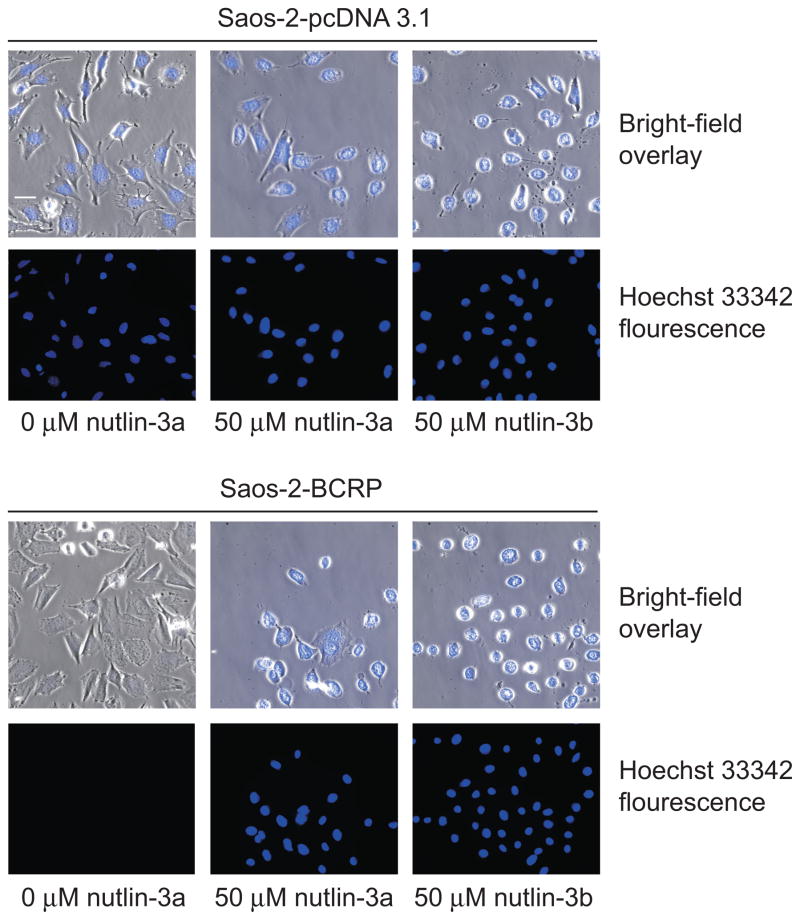

3.3. Nutlin-3a inhibits BCRP-mediated transport of Hoechst 33342

To determine whether nutlin-3a could also reduce the efflux of other BCRP substrates, the intracellular retention of another prototypical BCRP substrate, Hoechst 33342, was measured by flow cytometry in Saos-2 cells with and without BCRP expression. As BCRP over-expressing Saos-2 cells were incubated with increasing amounts of nutlin-3a, a dose-dependent decrease in the efflux of Hoechst 33342 was observed. Co-incubation of cells with nutlin-3a and Hoechst 33342 for 1 hour resulted in an almost complete inhibition of Hoechst 33342 efflux in Saos-2-BCRP cells (Figure 5A). This inhibition was comparable to that seen with the BCRP-specific inhibitor FTC (Figure S1). Co-incubation of cells with enantiomer nutlin-3b resulted in the same reduction in Hoechst 33342 efflux (Figure S2). Only events from viable cells were used for data analysis, and there was no difference in the viability between BCRP over-expressing and the vector control cells treated with either nutlin-3a or nutlin-3b (Figure S3). To determine if the reduced Hoechst 33342 efflux was dependent on p53 status, accumulation studies were also performed in p53 wild type MDCKII cells. The results indicated that nutlin-3a also reverses the Hoechst 33342 efflux in a p53 wild type cell line in a dose dependent manner (Figure 5B). Hence, nutlin-3a inhibition of BCRP-mediated transport of Hoechst 33342 is independent of cellular p53 status. In addition to the abrogation of efflux observed with flow cytometric methods, results from fluorescence imaging also demonstrated after treatment with nutlin-3a that Hoechst 33342 intracellular accumulation was dramatically restored in the Saos-2-BCRP cell line to levels comparable to Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 control cells (Figure 6). Treatment of cells with the enantiomer nutlin-3b resulted in the same reduction in Hoechst 33342 efflux, demonstrating that the two enantiomers have comparable effects on BCRP function (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Nutlin-3a dose-dependently inhibits BCRP efflux of Hoechst 33342, independent of p53 status. p53 null Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP, and p53 wild-type MDCKII-pcDNA3.1 and MDCKII-BCRP cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of nutlin-3a or vehicle control in the presence of Hoechst 33342 for 60 minutes. A, dose-dependent reduction of Hoechst 33342 efflux after nutlin-3a treatment assayed by flow cytometry in Saos-2 and MDCKII cells. B, quantitative assessment of nutlin-3a effects from representative flow cytometry experiments. Values are presented as mean ± SD. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

Nutlin-3 treatment increases the intracellular accumulation of Hoechst 33342 in Saos-2-BCRP cell lines. Wide-field fluorescence imaging of intracellular Hoechst 33342 (blue) in Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells in the presence or absence of 50 μM nutlin-3a or nutlin-3b for 60 minutes. Treatment with nutlin-3a and nutlin-3b strongly restored the accumulation of Hoechst 33342 in Saos-2-BCRP cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

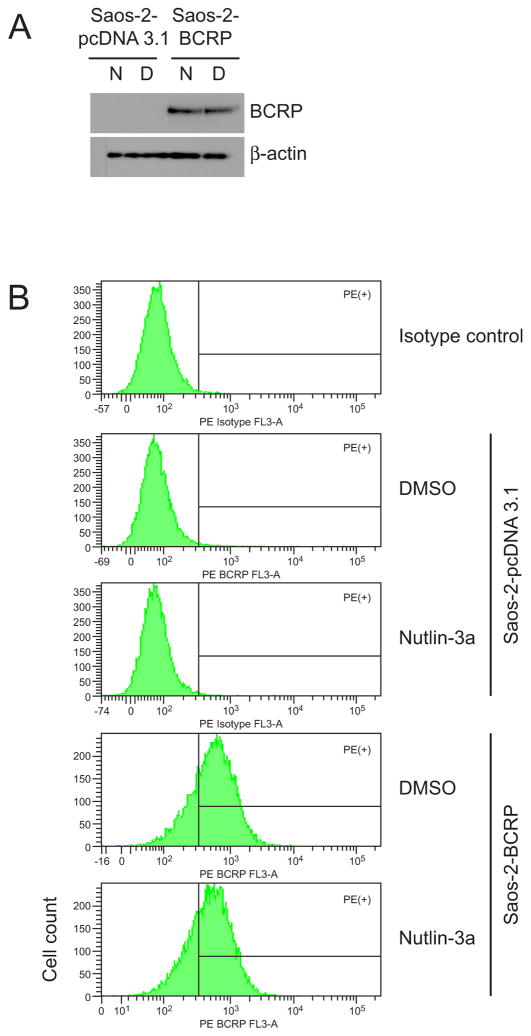

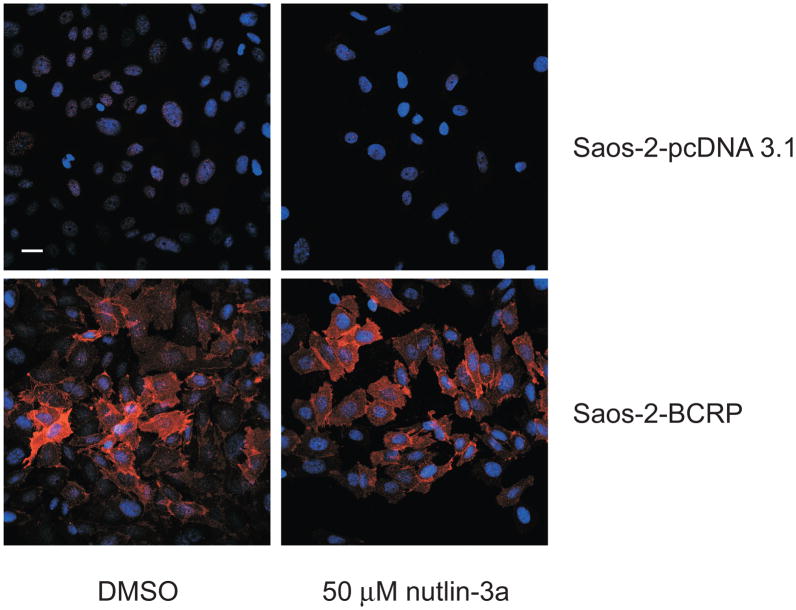

3.4. Nutlin-3a treatment does not alter BCRP expression or localization

To determine whether increased accumulation and sensitivity to mitoxantrone were a result of nutlin-3a inducing an alteration in BCRP protein levels, Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were treated at the highest nutlin-3a dose level used for functional studies (50 μM; 1 hr) and BCRP protein levels were measured. As shown in Figure 7, both Western blot (Figure 7A) and flow cytometric analysis (Figure 7B) demonstrated that total cellular protein levels of BCRP in Saos-2-BCRP cells were not altered in the presence of nutlin-3a. Since nutlin-3 has been shown to affect P-gp function, levels of P-gp protein were also assessed by Western blot. Although Saos-2 cells do not express detectable levels of P-gp [13, 19], it is possible that nutlin-3a treatment may up-regulate P-gp expression. As expected, nutlin-3a treatment did not significantly alter the expression of P-gp in either Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 or -BCRP cells (data not shown). Additional studies using confocal microscopy confirmed no obvious alteration in the membrane translocation of BCRP protein (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Nutlin-3a does not alter levels of BCRP protein expression. A, western blot analysis of the cellular protein expression of BCRP protein following nutlin-3a treatment (N, 50 μM nutlin-3a; D, equal volume DMSO). BCRP protein was detected using the monoclonal antibody BXP-53. B, flow cytometric analysis of the cell-surface expression of BCRP in response to nutlin-3a treatment. Cells were stained with the PE conjugated mouse anti-BCRP antibody (MAB4155P) and subjected to analysis. DAPI was added to cells to indicate viability. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Figure 8.

Nutlin-3a does not alter cellular localization of BCRP in Saos-2 cells. Confocal images taken of Saos-2 cells expressing BCRP treated with vehicle (DMSO) or nutlin-3a (50 μM, 90 minutes). Red represents BCRP protein and blue represents nuclear staining. Scale bar, 30 μm. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

3.5. Nutlin-3a is not a substrate for BCRP

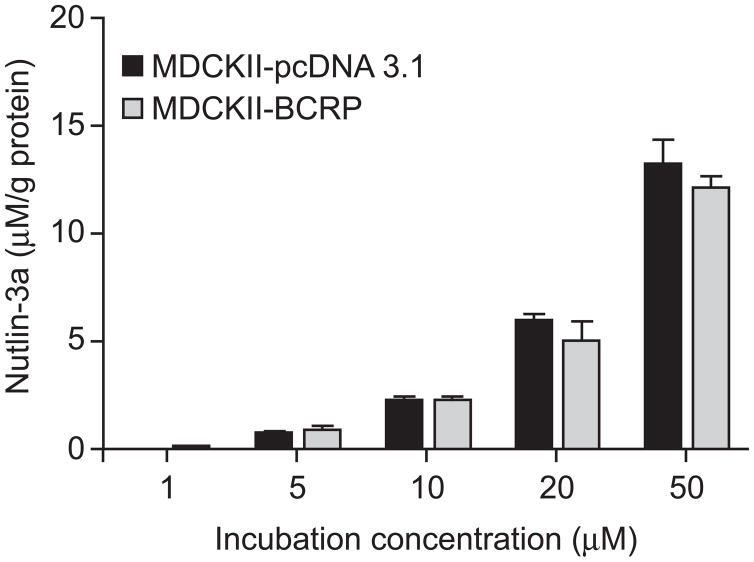

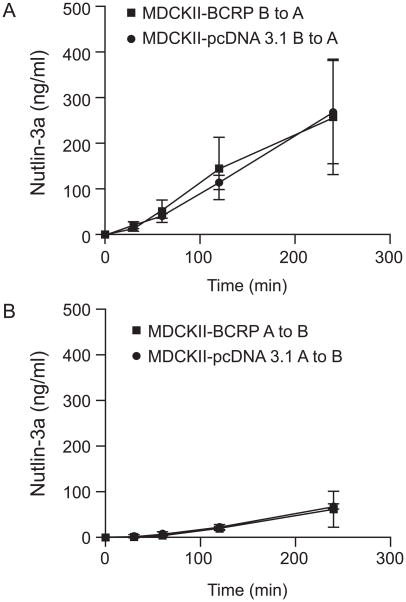

To test whether nutlin-3a is a BCRP substrate and thus inhibits BCRP function by competing with other substrates for transport, we examined the intracellular accumulation of nutlin-3a in MDCKII-pcDNA 3.1 and MDCKII-BCRP cells. Cells were incubated with 0, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 μM nutlin-3a at 37° C for 1 hour. No significant difference was observed in the amount of intracellular nutlin-3a between the two cell types at any concentration (up to 50 μM) (p>0.05) (Figure 9). These data suggest that nutlin-3a is not a substrate of BCRP. In addition to the intracellular accumulation assay, bidirectional transport studies were conducted using BCRP over-expressing and pcDNA3.1 vector control MDCKII cells. Nutlin-3a concentrations from either the apical or basolateral compartment were measured by LC-MS/MS and concentration vs. time plots were generated (Figure 10). The calculated R (REBCRP/ REpcDNA3.1) was 0.04, much less than the efflux ratio of 2, which is considered the cutoff for a drug to be a substrate [18]. Additionally, concentration vs. time plots of nutlin-3a in the presence and absence of the BCRP specific inhibitor Ko143 (5 μM) indicated that BCRP does not transport nutlin-3a (data not shown). Using the criteria outlined in the decision tree supported by the International Transporter Consortium, nutlin-3a is not a substrate of BCRP [20].

Figure 9.

No difference in intracellular accumulation of nutlin-3a in the presence of BCRP. MDCKII-pcDNA3.1 and MDCKII-BCRP cells were incubated with 0, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 μM nutlin-3a for 60 minutes. Intracellular nutlin-3a concentrations were determined by LC-MS/MS as previously described and normalized to total protein content. Data are presented as mean ± SD of triplicates.

Figure 10.

Trans-epithelial transport of nutlin-3a (10 μM) in MDCKII-pcDNA3.1 and MDCKII-BCRP cells indicates nutlin-3a is not a substrate of BCRP. Nutlin-3a was administered to one compartment (basolateral or apical) at time 0. After 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes, the concentrations of nutlin-3a appearing in the opposite compartment were measured by LC-MS/MS. Data are presented as mean ± SD of triplicates. A, translocation from the basolateral to the apical compartment; B, translocation from the apical to the basolateral compartment. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

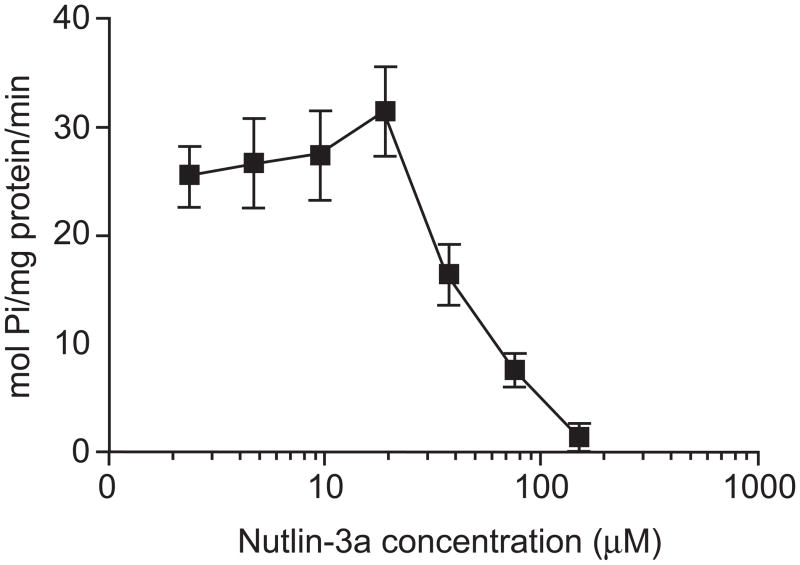

3.6. Nutlin-3a inhibits the ATPase activity of BCRP

To investigate inhibition as a mechanism for the nutlin-3a-induced reduction in efflux of BCRP substrates, BCRP ATPase activity in response to nutlin-3a treatment was measured using a previously described ATPase activity assay [21, 22]. BCRP transporter activity was determined by assaying both activation and inhibition in the presence of a known activator of the transporter (i.e., sulfasalazine). Increasing concentrations of nutlin-3a (0.1 μM to 150 μM) did not stimulate ATPase activities from the baseline measurements (data not shown). In the corresponding inhibition assay, however, higher concentrations of nutlin-3a demonstrated a strong capacity to inhibit ATPase activity (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Nutlin-3a dose dependently inhibited BCRP ATPase activity. The relative vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity of Sf9 insect cell membranes over-expressing wild-type ABCG2 is represented as mol Pi/mg protein/min in the presence of increasing concentrations of nutlin-3a with a known BCRP substrate, sulfasalazine. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

4. Discussion

This is the first study demonstrating that nutlin-3a inhibits BCRP activity. Our data suggest that resistance to mitoxantrone can be strongly reversed by nutlin-3a in BCRP over-expressing cells. Nutlin-3a treatment resulted in a dose-dependent increase in the intracellular accumulation of BCRP substrates in BCRP over-expressing cells. To understand the mechanism behind these observations, a series of studies were performed that clearly demonstrated nutlin-3a inhibited BCRP efflux independent of p53, without altering BCRP protein expression or subcellular localization. Additionally, studies examining the intracellular accumulation of nutlin-3a along with bi-directional transport across MDCKII monolayer cells supported the conclusion that nutlin-3a is not a substrate of BCRP, but does act as an inhibitor through interference with BCRP ATPase activity.

Multi-drug resistance is a major obstacle in the success of cancer treatment. Among the ABC family of transporters, P-gp, MRP1, and BCRP are three major members associated with multidrug resistance [23]. BCRP, the most recently discovered among these three major transporters [23, 24], confers resistance to many anti-cancer drugs used clinically including mitoxantrone, methotrexate, doxorubicin, daunorubicin, topotecan, and SN38 [25, 26]. Utilization of an agent such as nutlin-3a, which inhibits BCRP, in combination with an anti-cancer agent that is a BCRP substrate (such as mitoxantrone or topotecan) may potentially increase the intracellular drug levels and lead to greater anti-tumor activity. In fact, when nutlin-3 was combined with the BCRP and P-gp substrate topotecan for 5 days, an 82-fold reduction in the tumor burden of retinoblastoma was reported [5]. It is important to note however that synergistic effects may differ depending on the cell type or co-administered drug, and antagonism may be observed if the schedule of administration were to change [27, 28].

Since nutlin-3a re-activates p53 in cells co-expressing MDM2 [1, 29], the question exists of whether the reversal of ABC transporter activity is dependent on the p53 pathway. Our data along with the previous study by Michaelis et al. clearly demonstrate that the inhibition of ABC transporter efflux by nutlin-3 occurs independently of cellular p53 status [11]. Also supporting this conclusion is the observation that nutlin-3b, the non-active enantiomer, demonstrated BCRP inhibition comparable to the active enantiomer nutlin-3a.

Michaelis et al. demonstrated that nutlin-3 stimulated P-gp ATPase activity in isolated membranes and exerted a negative effect on P-gp activity by acting as a competing substrate [11]. In contrast, our studies demonstrate by multiple approaches that nutlin-3a does not act as a competitive inhibitor of BCRP. First, the amount of intracellular nutlin-3a and the nutlin-3a IC50 were unaffected by the over-expression of BCRP. Second, the calculated efflux ratios from the bidirectional transport assay were <2 in MDCKII cells. Lastly, nutlin-3a did not activate ATPase activity as measured by released inorganic phosphate (Pi) in a BCRP over-expression system. On the other hand, nutlin-3a dose dependently decreased the ATPase activity in the inhibition assay.

Previous studies have implicated BCRP translocation from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm as a mechanism by which BCRP function can be regulated [30]. We demonstrated in our studies via Western blot and flow cytometry that neither total BCRP protein levels nor the subcellular localization of BCRP changed during the time period that efflux studies were conducted. These findings are important because since BCRP is involved in drug disposition and many other physiological processes in the body, using a drug that alters BCRP expression and/or localization would likely have global effects. Specifically, BCRP is expressed at the blood brain barrier, placenta, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, liver and biliary tract, and BCRP activity is important for intestinal absorption, brain penetration, renal elimination and hepatobiliary excretion of substrates.

Along with BCRP, P-gp and MRP1 also play a critical role in pharmacokinetic interactions of anti-cancer agents, affecting the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) processes. Concomitant treatment of elacridar (GF120918), an inhibitor of BCRP and P-gp, resulted in a 2.4 fold increase in bioavailability and systemic exposure of oral topotecan in adults with cancer [31]. Similarly, concomitant treatment with gefitinib, another inhibitor of BCRP and P-gp, increased bioavailability of oral irinotecan in mice [32] and in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors [33]. Our lab recently demonstrated that gefitinib enhanced topotecan penetration in gliomas in mice [34]. As an inhibitor of multiple major efflux transporters including BCRP, P-gp and MRP1, nutlin-3a may have impact on pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and importantly the safety of many clinically used drugs. Therefore, it is crucial that transporter related drug-drug interactions be carefully addressed in future preclinical studies.

In conclusion, this is the first study demonstrating that nutlin-3a inhibits BCRP activity. Our data show that nutlin-3a dose dependently inhibits BCRP-mediated transport of multiple BCRP substrates and synergistically reverses the drug resistance to anticancer agent mitoxantrone. The likely mechanism of this effect is the inhibition of BCRP ATPase activity, as we have clearly demonstrated through multiple lines of investigation that nutlin-3a is not a substrate of BCRP. Thus, using nutlin-3a in combination with anti-cancer agents that are BCRP or other ABC transporter substrates would require additional studies to identify potentially significant drug-drug interactions due to the critical role of these transporters in drug ADME.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Effect of FTC on the BCRP efflux of Hoechst 33342. Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were incubated with DMSO or FTC in the presence of Hoechst 33342 for 60 minutes. Data are representative of one experiment performed in triplicate. Error bar, ± SD. *p <0.05, ***p <0.0001.

Figure S2. Effect of nutlin-3b on efflux of Hoechst 33342. Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were incubated with DMSO or nutlin-3b in the presence of Hoechst 33342 for 60 minutes. Data are representative of one experiment performed in triplicate. Error bar, ± SD. ***p<0.0001.

Figure S3. Viability ratio of Saos-2-BCRP/ Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 during the Hoechst 33342 efflux study. Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were incubated with 50 μM nutlin-3a or nutlin-3b in the presence of Hoechst 33342 for 60 minutes. Data are representative of one experiment performed in duplicate. Error bar, ± SD. p > 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US Public Health Service Childhood Solid Tumor Program Grant No. CA23099, Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant No. CA21765, and by American, Lebanese, and Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). We thank Dr. Feng Bai for LC-MS/MS assistance. We thank Jennifer Peters for her help in the confocal and fluorescence imaging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Fan Zhang, Email: fan.zhang@stjude.org.

Stacy L. Throm, Email: stacy.throm@stjude.org.

Laura L. Murley, Email: llmurley@hotmail.com.

Laura A. Miller, Email: laura.miller@stjude.org.

D. Steven Zatechka, Jr., Email: steve.zatechka@stjude.org.

R. Kiplin Guy, Email: kip.guy@stjude.org.

Rachel Kennedy, Email: rjeankennedy@gmail.com.

Clinton F. Stewart, Email: clinton.stewart@stjude.org.

References

- 1.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, Carvajal D, Podlaski F, Filipovic Z, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarek G, Ojala PM. p53 reactivation kills KSHV lymphomas efficiently in vitro and in vivo: new hope for treating aggressive viral lymphomas. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2205–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.18.4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tovar C, Rosinski J, Filipovic Z, Higgins B, Kolinsky K, Hilton H, et al. Small-molecule MDM2 antagonists reveal aberrant p53 signaling in cancer: implications for therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1888–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507493103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Maerken T, Ferdinande L, Taildeman J, Lambertz I, Yigit N, Vercruysse L, et al. Antitumor activity of the selective MDM2 antagonist nutlin-3 against chemoresistant neuroblastoma with wild-type p53. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1562–74. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laurie NA, Donovan SL, Shih CS, Zhang J, Mills N, Fuller C, et al. Inactivation of the p53 pathway in retinoblastoma. Nature. 2006;444:61–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaRusch GA, Jackson MW, Dunbar JD, Warren RS, Donner DB, Mayo LD. Nutlin3 blocks vascular endothelial growth factor induction by preventing the interaction between hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha and Hdm2. Cancer Res. 2007;67:450–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secchiero P, Corallini F, Gonelli A, Dell'Eva R, Vitale M, Capitani S, et al. Antiangiogenic activity of the MDM2 antagonist nutlin-3. Circ Res. 2007;100:61–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000253975.76198.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binder BR. A novel application for murine double minute 2 antagonists: the p53 tumor suppressor network also controls angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;100:13–4. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255897.84337.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Supiot S, Hill RP, Bristow RG. Nutlin-3 radiosensitizes hypoxic prostate cancer cells independent of p53. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:993–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peirce SK, Findley HW. The MDM2 antagonist nutlin-3 sensitizes p53-null neuroblastoma cells to doxorubicin via E2F1 and TAp73. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michaelis M, Rothweiler F, Klassert D, von Deimling A, Weber K, Fehse B, et al. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by the murine double minute 2 antagonist nutlin-3. Cancer Res. 2009;69:416–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckford PD, Sharom FJ. ABC efflux pump-based resistance to chemotherapy drugs. Chem Rev. 2009;109:2989–3011. doi: 10.1021/cr9000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wierdl M, Wall A, Morton CL, Sampath J, Danks MK, Schuetz JD, et al. Carboxylesterase-mediated sensitization of human tumor cells to CPT-11 cannot override ABCG2-mediated drug resistance. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:279–88. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leggas M, Panetta JC, Zhuang Y, Schuetz JD, Johnston B, Bai F, et al. Gefitinib modulates the function of multiple ATP-binding cassette transporters in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4802–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'argenio DZ, Schumitzky A, Wang X. ADAPT 5 User’s Guide. Pharmacokinetic/ Pharmacodynamic Systems Analysis Software; Los Angeles: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:621–81. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai F, Zhu F, Tagen M, Miller L, Owens TS, Mallari J, et al. Determination of nutlin-3a in murine plasma by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2009;51:915–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang S-M, Stifano T. Graft Guidance for Industry Drug Interaction Studies — Study Design, Data Analysis, and Implications for Dosing and Labeling. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsson P, Englund G, Ahlin G, Bergstrom CA, Norinder U, Artursson P. A global drug inhibition pattern for the human ATP-binding cassette transporter breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:19–30. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.124768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giacomini KM, Huang SM, Tweedie DJ, Benet LZ, Brouwer KL, Chu X, et al. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:215–36. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarkadi B, Price EM, Boucher RC, Germann UA, Scarborough GA. Expression of the human multidrug resistance cDNA in insect cells generates a high activity drug-stimulated membrane ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4854–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glavinas H, Kis E, Pal A, Kovacs R, Jani M, Vagi E, et al. ABCG2 (breast cancer resistance protein/mitoxantrone resistance-associated protein) ATPase assay: a useful tool to detect drug-transporter interactions. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:1533–42. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.014605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robey RW, To KK, Polgar O, Dohse M, Fetsch P, Dean M, et al. ABCG2: a perspective. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doyle LA, Yang W, Abruzzo LV, Krogmann T, Gao Y, Rishi AK, et al. A multidrug resistance transporter from human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15665–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polgar O, Robey RW, Bates SE. ABCG2: structure, function and role in drug response. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4:1–15. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao Q, Unadkat JD. Role of the breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) in drug transport. AAPS J. 2005;7:E118–33. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiozawa K, Nakanishi T, Tan M, Fang HB, Wang WC, Edelman MJ, et al. Preclinical studies of vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid) combined with cytosine arabinoside and etoposide for treatment of acute leukemias. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1698–707. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voigt W, Bulankin A, Muller T, Schoeber C, Grothey A, Hoang-Vu C, et al. Schedule-dependent antagonism of gemcitabine and cisplatin in human anaplastic thyroid cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2087–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vassilev LT. Small-molecule antagonists of p53-MDM2 binding: research tools and potential therapeutics. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:419–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mogi M, Yang J, Lambert JF, Colvin GA, Shiojima I, Skurk C, et al. Akt signaling regulates side population cell phenotype via Bcrp1 translocation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39068–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruijtzer CM, Beijnen JH, Rosing H, ten Bokkel Huinink WW, Schot M, Jewell RC, et al. Increased oral bioavailability of topotecan in combination with the breast cancer resistance protein and P-glycoprotein inhibitor GF120918. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2943–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart CF, Leggas M, Schuetz JD, Panetta JC, Cheshire PJ, Peterson J, et al. Gefitinib enhances the antitumor activity and oral bioavailability of irinotecan in mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7491–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furman WL, Navid F, Daw NC, McCarville MB, McGregor LM, Spunt SL, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor enhances the bioavailability of oral irinotecan in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4599–604. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carcaboso AM, Elmeliegy MA, Shen J, Juel SJ, Zhang ZM, Calabrese C, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib enhances topotecan penetration of gliomas. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4499–508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Effect of FTC on the BCRP efflux of Hoechst 33342. Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were incubated with DMSO or FTC in the presence of Hoechst 33342 for 60 minutes. Data are representative of one experiment performed in triplicate. Error bar, ± SD. *p <0.05, ***p <0.0001.

Figure S2. Effect of nutlin-3b on efflux of Hoechst 33342. Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were incubated with DMSO or nutlin-3b in the presence of Hoechst 33342 for 60 minutes. Data are representative of one experiment performed in triplicate. Error bar, ± SD. ***p<0.0001.

Figure S3. Viability ratio of Saos-2-BCRP/ Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 during the Hoechst 33342 efflux study. Saos-2-pcDNA3.1 and Saos-2-BCRP cells were incubated with 50 μM nutlin-3a or nutlin-3b in the presence of Hoechst 33342 for 60 minutes. Data are representative of one experiment performed in duplicate. Error bar, ± SD. p > 0.05.