Abstract

The study explores Black adolescent detainees academic potential and motivation to return to school to inform best practices and policies for juvenile reentry to educational settings. Adolescent detainees (N = 1,576) who were recruited from one male and one female youth detention facility, responded to surveys that assessed post-detention educational plans, as well as social and emotional characteristics, and criminal history. Multivariate analysis techniques were used to compare factors across race and gender, and plot linear relationships between key indicators of academic potential with associate factors. Findings revealed that youth were more likely to evince academic potential when they had a healthy level of self-esteem, adequate future goal orientation, positive mood, family and community involvement, fewer traumatic events, and less delinquent activity.

Currently, African American's representation in the juvenile justice system (30%) is twice their representation in the general population (Rozie-Battle, 2002). In addition, only half of Black students who start high school graduate within four years, compared to 75% of White students (Edney, 2004; Valentine, 2005). Research evidence suggests that the juvenile justice system and current educational policies fail to meet the basic educational and remedial needs of socially disadvantaged African American children (Painter, 2008). Gehring (2005) indicated that nationwide, most juvenile correctional facilities offer substandard educational accommodations to youth detainees. Consequently, African American adolescent detainees, incarcerated for even minor offenses, can exit the juvenile justice system with severe educational deficits (Morrison & Epps, 2002). The purpose of this study is to explore the academic potential of Black youth in juvenile detention centers to establish priorities for detention-based education and program designed to reintegrate former youth detainees into mainstream schools

Literature review

Studies that evaluate the educational needs of youth who are detained in Juvenile Detention Facilities (JDFs) have been documented in the United States for nearly a century. In 1920, an article in the Journal of Education recommended a normal school environment for youth detainees, with modern equipment for teachers and students (Drewry, 1920). In more recent history, many challenges have surfaced related to educational services for detained youth, including identifying youth with special education needs (Brown & Robbins, 1979; Glick & Sturgeon, 1999); meeting federal standards for detention-based education with limited funding (Roush, 1983); addressing mental health, substance use problems and trauma among youth detainees (Francis, 1995; McPherson, 1993; Smith, 1998); aftercare planning (Hellriegel & Yates, 1999); and addressing cultural needs and institutional racism (Clinkenbeard, Navaratil, Yost, Hill, & Roush, 1996). In 1992, the Juvenile Justice Delinquency Prevention Act mandated educational opportunities to youth detainees, however, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention found that more than 75% of JDFs violated at least one regulation related to providing educational opportunities for youth detainees (Painter, 2008).

One study noted that 68% of youth detainees in one sample identified symptoms of a mental health disorder (Nordness, et al., 2002). Female detainees have demonstrated distinct mental health issues related to having higher exposure to sexual trauma (Kelly, Martinez, & Medrano, 2004). Research evidence suggests that the growing number of youth detainees have exacerbated some of the existing problems, leading to more recidivism over the last decades. An analysis of national trends demonstrated that overcrowded JDFs exhaust educational and health services. The study identified King County (Seattle) and Cook County (Illinois) as facilities that have demonstrated reform by using community-based approaches (Griffinger & Texeira, 2001).

Youth typically enter JDFs with more severe educational deficits than youth with no history of juvenile justice involvement (Keith & McCray, 2002). Literacy, for example was noted to impact learning continuity among youth detainees (Drakeford, 2002). The study found that improving literacy skills among youth detainees also reduced recidivism. Studies have noted that the provisions of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act for special education service delivery are also applicable to JDFs (Cramer Brooks, 2008; Leone, Drakeford, & Meisel, 2002). However, today many JDFs offer substandard special education programs. One study recommends more closely scrutinizing special education offerings at JDFs and specially designed courses and certification programs geared toward JDFs (Bailey, 2008).

Character building and decision making programs have also demonstrated efficacy in enhancing the academic potential of youth detainees (Martinez, 2008). An exploratory study found that incarcerated youth in two Nevada youth detention facilities who possessed higher levels of decision-making competence, scored higher on a post-detention success scale (Evans, Brown, & Killian, 2002). Youth who are detained seem to have a clear understanding of their needs while detained. A survey of youth detainees in St. Louis revealed that the greatest perceived needs among detainees were to learn how to make better choices and cultural diversity education (Giovanni, 2002).

Overall, the literature demonstrates that a comprehensive approach to dealing with the educational needs of youth detainees is necessary to help them reach their academic potential. One study noted that a truly integrative approach will provide robust opportunities for JDFs and schools to collaborate, to provide for a seamless transition of youth from the detention center back to the school (Hellriegel & Yates, 1999). In the case study example, the public school district collaborated with the juvenile justice system, by sharing staff resources, having joint training, having interagency involvement with transition plans, and increasing parental involvement. Other successful programs have emphasized: improving the quality of education in JDFs to provide a challenging experience (DuCloux, 2003); peer tutoring programs (David, 2005); having social workers provide detainees with educational material (Sarri & Shook, 2005); technical programs and GED preparation (Conlon, Harris, Nagel, Hillman, & Hanson, 2008); and positive behavior support (Nelson, Sprague, Jolivette, Smith, & Tobin, 2009).

Conceptual framework

The existing literature informs the conceptual framework of this study. However, notably race and gender are not explored as meaningful key indicators in the majority of the studies. The current study seeks to understand the academic potential of Black adolescent detainees by using a “participant inquiry” and strength-based approach to research (Wiggan, 2007). The research realizes the social and historical context and failures of educational and juvenile justice policies and practices, and appreciates the resilience of the participants. Every JDF contains examples of boys and girls who have the potential to achieve in school, regardless of immeasurable social disadvantages. Exploring characteristics that vary on the spectrum of ability provide a greater level of depth and insight into factors that are associated with achievement potential among Black youth detainees.

Based on the literature, the primary hypothesis of this study was that youth detainees with higher levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy, future orientation, and family and community involvement, and lower levels of depression, childhood trauma, and delinquent activity will exhibit more academic potential. The research that emphasized the importance of dealing with mental health issues, led us to the hypothesis that youth detainees with lower levels of depression and higher levels of self-esteem and self-efficacy would evince higher levels of academic potential. In addition, studies cited that linked academic success to character building and decision making, informed our hypothesis that future goal oriented and prosocial behavior was vital to academic potential. Finally, studies cited that demonstrated the importance of family involvement and community-based approaches, suggest that family and community involvement could enhance academic potential. This study will also assess race and gender differences to determine any unique indicators of academic potential among Black males and Black female detainees.

Methods

Participants

The participants consisted of male and female adolescent social offenders sentenced to two gender specific, secured JDFs. The JDFs served youth from the entire state and were privately operated under contracts with the Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice. The participants were typically mandated to the JDFs for 90 days, although sentences ranged between 30 and 180 days. At any given time about 300 boys and 120 girls were residing in the two facilities. The youths' age ranged from 12 to 18 years of age. For the present study, only responses from youth detainees who attended school within the month prior to detention were analyzed.

Procedure

Juvenile detainees within 3 days of entering the facility, were approached by a community interviewer to solicit their participation in Project SHARP (Stop HIV and Alcohol-Related Problems), a program addressing the prevention of HIV and alcohol and other drug (AOD) use among juvenile detainees. Researchers worked with the facility staff and provided them with the participant eligibility criteria. The staff then provides researchers with the names of those who meet that criteria. Dependent on the facility, the staff person was either a counselor or an administrator. The youth were informed that their participation was voluntary and that the information they provided would be handled confidentially and not shared with the YDC staff. Those who agreed signed an assent form, which authorized the researcher to request permission from parents or guardian for the youths to participate. The parents or guardians of these youth were then sent a letter that described the study and informed that their child had agreed to participate. In total, 4,031 youth were approached and 2,766 (68.6%) agreed to participate, and 2,280 (56.6%) actually participated.

The parents or guardians were then asked to call the principal investigator at an indicated phone number if they had any questions or needed additional information about the study. Further, they were asked to provide either passive consent by not replying to the letter or else to deny consent by signing an enclosed form and returning it by a specified date in a stamped, addressed envelope that was enclosed. Approximately 4 weeks after entering the facility, participants completed a baseline questionnaire through interviews. Trained community interviewers who resided in the communities located near the two JDFs conducted face to-face interviews to collect baseline information on several measures. These community interviewers received an 8-h group training session, where the project director discussed interviewing techniques and reviewed and clarified each question in the interview protocol. All interviewers were required to complete a criminal background check with the Department of Juvenile Justice. Female interviewers were consistently matched with female participants, while either a male or female interviewer interviewed male participants. Data were collected over a 3 year period between 1999 and 2001.

Measures

Academic potential was the central construct of this study and represented academic resilience indicators that enhanced the likelihood that detainee could successfully reenter school. Study participants responded to the yes or no question, “Do you plan to go back to school when you get out?” In addition, participants responded to the question: “How well do you do in school?” Response options were: (1) Mostly A's; (2) Some A's and some B's; (3) Mostly B's; (4) Some B's and some C's; (5) Mostly C's; (6) D's and F's; or (7) Are you failing most classes? To streamline the analysis, the seven categories were collapsed to create four categories consisting of (1) Below Average – F's and D's; (2) Average – Some Bs, but mostly Cs; (3) Good – Some A's but mostly Bs; and (4) Very Good – Mostly A's.

Self-esteem represented the detainees intrinsic values of self-worth, confident and positive self-regard. The self-esteem of the participants was measured using The Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). The scale consists of 10 items rated on a four- point scale with response options ranging from one “strongly agree” to four “strongly disagree.” Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. The scale was initially developed for adolescents but has since been widely used with both younger children and adults.

Self-efficacy referred to the detainee's sense that he/she had mastery of their life-chances and the ability to control their own fate. Self-efficacy was measured with the Mastery Scale (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978), a 7-item scale with Likert rating ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Sample items include: “ I have little control over things that happen to me;” and “There is really no way I can solve some of the problems I have.”

Future Orientation signified the detainees' tendency to be forward thinking, as represented by being keen to future personal life events and circumstances. Future Orientation was assessed with the Heimberg Future Time Perspective Inventory (FTP). The FTP is a 25 item, but for this study 12 items were selected. Response options ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree” with higher scores indicating a longer future time perspective (Heimberg, 1963).

Depression represented the detainees' internal and enduring state of sadness and despondence that may impair normal functioning. Depression was assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CESD) Short Form. The CES-D consists of 9 items, rated on a four-point scale according to how frequently they were experiences the previous week. The scale is sensitive to changes in depressive symptoms that may occur over time (Radloff, 1977).

Family Involvement signified the extent to which the detainee participated in meaningful and routine family activities. Family-social perceptions was assessed using a 11-item rating form that was developed by the principal investigator. The device was used to assess the participants' perceptions of their families. The scale included questions related to: problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavior control, and general functioning. Items were rated on a 4-point scale form strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Community Involvement signified the extent to which the detainee participated in regular and meaningful activities in their neighborhoods. Community involvement was assessed by asking participants about their involvement in school, work, church, clubs, organized sports, or other community organizations (e.g., neighborhood groups, self-help groups) during the past month. At all times, participants will indicated if they had been involved in each activity (yes = 1, no = 0) as well as their overall level of involvement in each activity on a 4-point scale (options ranged from 0 to 3, with wording varying depending on the activity).

Childhood Trauma represented the severity, frequency, and nature of emotional, physical and sexual abuse that the participant may have experienced prior to detention. Trauma was measured using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). Researchers used 24 items from the original 28-item self-report retrospective inventory. The scale measures childhood or adolescent abuse and neglect on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Never True to Very Often True. The CTQ contains five subscales, three assessing abuse (Emotional, Physical, and Sexual) and two assessing neglect (Emotional and Physical). Each subscale has five items. A 5-point frequency of occurrence scale is used: (1) never true, (2) rarely true, (3) sometimes true, (4) often true, and (5) very often true. Test-retest reliabilities with testing over an average 3.6-month period yielded stability coefficients near .80, while the validity ranges from .50 to .75 (Bernstein & Fink, 1998).

Delinquent Activity represented the frequency, severity, and nature of the detainees criminal involvement that may or may not be related to the detainees' immediate involvement in the juvenile justice system. Delinquent Activity was measured using a scale based on the Seattle Survey Instrument (Binder, Geis, & Bruce, 1988). This instrument assessed self-reported delinquent activity three months before entering the detention facility. In keeping with the original categorization of offences as described by Binder et al. (1988), these activities were classified in three indexes (a) a serious crime index (21 items, i.e. sell something you had stolen, break into a locked car to get something from it, pull a knife, gun or some other weapon on someone just to let them know you mean business); (b) a school and family index (7 items, i.e. been suspended or expelled from school, hit one of your parents/guardians); and (c) a drug index (2 items, sell any type of drugs, hold on to any type of drugs for someone). The response Likert categories were ‘never’, ‘once or twice’, ‘many times’ and ‘often’ (range: 1-4). Scores were created for each subscale offense index and the total delinquency scale had a score ranging from 1 to 4. Finally, recidivism was measured dichotomously by asking: ‘Have you ever been locked up before this time?’

Socio-Demographic and Background Variables. Researchers developed a questionnaire to assess socio-demographic and other background characteristics of participants. Age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, family structure, parent status, as well as medical, educational, residential, and juvenile justice history was gathered.

Analysis Plan

The principle analytic technique used in this study was a multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) for academic potential among Black detainees, with White detainees serving as a comparison group. General linear modeling approaches were used to reveal differences in the relationship between academic potential and associated variables along race and gender lines. The hypothesized relationships between academic potential and external measures were tested with a P-value of .01 where the p was less than .01, the likelihood that the reported result is due to random chance factors is only 1 percent. Means plots are used throughout the results to display the linear relationship between various indicators of academic potential and hypothesized covariates. The plots include a dashed reference line on the Y-axis that marked the estimated mean of the variable of interest. The reference line is useful for determining the distribution of scores around the mean for various levels of pre-detention grades.

Results

Descriptive information

Participants were 1,576 adolescents who were detained at a juvenile detention center in the southeastern region of the United States and had been attending school immediately prior to detention. The average age of participants was 15 years old, with a range of 11 to 18, and the average current grade was 8th, with a range of 5th to 12th. The race-gender distribution of participants was 407 Black males, 238 White males, 581 Black females, and 350 White females.

Plans to return to school

Among the youth detainees, 92.6% reported that they planned to return to school after release. Chi-square (X = 37.61; df = 3; p < .001) analysis revealed significant differences between race-gender groups. Black females were the most likely to plan to return to school with 97.1%, followed by White females (92.9%), Black males (89.9%), and White males (85.7%). Across all race-gender groups, the estimated grade point average based on their reported grades was 2.4. Black females reported the highest grades of 2.6 and Black males reported the lowest with 2.3. White females' and White males' estimated grades were both 2.4.

Analysis of variance revealed that participants' plans to return to school were influence by their age, grade level, and grades in school at the time of detention. Compared to youth who did not plan to return to school, those planning to return were significantly younger (F = 92.48, df = 1, p > .001), in lower grade levels (F = 39.09, df = 1, p > .001), and had higher grade averages (F = 5.58, df = 1, p > .05). More than half of all participants (52%) indicated that they eventually wanted to go to college after graduating from high school. For both Black and White females, 59% responded that they planned to attend college. For Black males, 45%, and for White males 36% planned to attend college. When assessing future aspirations, the top five career choices for Black males were: (1) athlete; (2) undecided; (3) construction; (4) computer analyst or programmer; and (5) military. For Black females the top five choices were: (1) medical profession including doctors and nurses; (2) beauty industry; (3) lawyer; (4) undecided; and (5) teacher.

Influences on Academic Potential across Races

MANOVA was used to test the hypothesis that youth detainees with higher levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy, future orientation, and family and community involvement, and lower levels of depression, childhood trauma, and delinquent activity will exhibit more academic potential, as measured by their pre-detention grades and desire to return to school. Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations and F-ratios of factors that have a hypothesized relationship with academic potential among Black and White youth detainees. The table marks variables that are significant by race and reported grades prior to detention.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and F Ratios of Factors Associated with Pre-detention Academic Achievement among Black and White Detainees

| Grades before detention | F Ratio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Race | Below Avg. (M, SD) |

Avg. (M, SD) | Good (M, SD) | Very Good (M, SD) |

Total (M, SD) | Race | Grades |

| Self-Esteem | Black | 25.75 (3.97) | 26.07 (3.40) | 26.52 (3.26) | 26.04 (3.79) | 26.20 (3.57) | 7.36* | 5.65** |

| White | 24.39 (4.82) | 25.62 (3.48) | 25.75 (3.64) | 26.03 (3.50) | 25.49 (3.96) | |||

| Total | 25.11 (4.43) | 25.94 (3.41) | 26.27 (3.41) | 26.04 (3.68) | 25.94 (3.73) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Self-Efficacy | Black | 13.27 (3.82) | 13.99 (3.36) | 13.44 (3.42) | 13.63 (3.87) | 13.53 (3.62) | 5.33* | 1.70 |

| White | 13.58 (3.68) | 13.44 (3.59) | 12.83 (3.46) | 12.34 (3.57) | 12.90 (3.59) | |||

| Total | 13.41 (3.75) | 13.83 (3.42) | 13.24 (3.44) | 13.13 (3.81) | 13.30 (3.62) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Future Orientation | Black | 40.55 (8.12) | 41.27 (7.06) | 42.21 (7.14) | 43.08 (7.99) | 42.10 (7.60) | 2.28 | 10.49** |

| White | 38.72 (8.55) | 40.92 (7.13) | 41.96 (7.27) | 42.51 (8.02) | 41.26 (7.96) | |||

| Total | 39.69 (8.36) | 41.17 (7.05) | 42.13 (7.18) | 42.86 (7.99) | 41.79 (7.74) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Depression Scale | Black | 23.06 (6.45) | 25.26 (6.07) | 25.54 (5.98) | 24.30 (6.13) | 24.73 (6.17) | 1.83 | 3.76* |

| White | 23.72 (6.96) | 24.74 (6.13) | 23.97 (6.79) | 23.49 (6.93) | 23.81 (6.82) | |||

| Total | 23.37 (6.69) | 25.11 (6.07) | 25.02 (6.30) | 23.99 (6.45) | 24.39 (6.43) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Family Involvement | Black | 28.26 (8.32) | 30.31 (7.23) | 31.67 (6.96) | 32.94 (7.75) | 31.35 (7.62) | 38.31** | 8.26** |

| White | 27.29 (7.98) | 27.51 (6.69) | 28.32 (7.71) | 27.99 (7.54) | 27.90 (7.64) | |||

| Total | 27.80 (8.16) | 29.51 (7.17) | 30.56 (7.38) | 31.04 (8.03) | 30.07 (7.80) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Community Involvement |

Black | 16.18 (5.07) | 17.08 (4.27) | 18.07 (4.45) | 18.95 (4.75 | 17.92 (4.72) | 62.04** | 11.73** |

| White | 14.61 (4.25) | 14.95 (4.26) | 15.44 (4.42) | 15.89 (5.07 | 15.34 (4.60) | |||

| Total | 15.45 (4.76) | 16.47 (4.36) | 17.20 (4.61) | 17.78 (5.09 | 16.96 (4.84) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Childhood Trauma | Black | 38.67 (16.50) | 35.66 (11.61) | 34.20 (11.46) | 35.73 (14.83) | 35.55 (13.53) | 0.00 | 4.82** |

| White | 38.10 (14.74) | 33.26 (10.67) | 35.56 (12.72) | 37.18 (13.89) | 36.54 (13.53) | |||

| Total | 38.40 (15.67) | 34.98 (11.37) | 34.65 (11.90) | 36.29 (14.47) | 35.92 (13.54) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Delinquent activity | Black | 47.87 (13.21) | 44.59 (11.81) | 42.49 (10.59) | 40.68 (10.26) | 43.05 (11.34) | 10.01** | 20.39** |

| White | 45.04 (11.02) | 41.31 (7.71) | 40.26 (8.71) | 40.43 (9.07) | 41.58 (9.57) | |||

| Total | 46.54 (12.29) | 43.66 (10.88) | 41.75 (10.05) | 40.58 (9.81) | 42.51 (10.74) | |||

p < .01

p < .001

Higher levels of self-esteem, future orientation, and family and community involvement, and lower levels of depression, childhood trauma, and delinquent activity had a significant relationship with pre-detention grades. Of the eight variables analyzed, self-efficacy was the only variable that did not have a significant relationship with pre-detention grades. On Table 1, mean scores with a negative relationship with pre-detention grades, such as childhood trauma and depression, get smaller when reading from left to right as academic performance increases. The opposite is true for the variables, such as family activity and community involvement, with a positive relationship with academic achievement. Five of the eight variables were significant for race. When compared to White detainees, Black detainees reported higher levels of self-esteem, family activities and community involvement, and less childhood trauma. Black detainees also reported more behavior problems and higher levels of depression than White detainees.

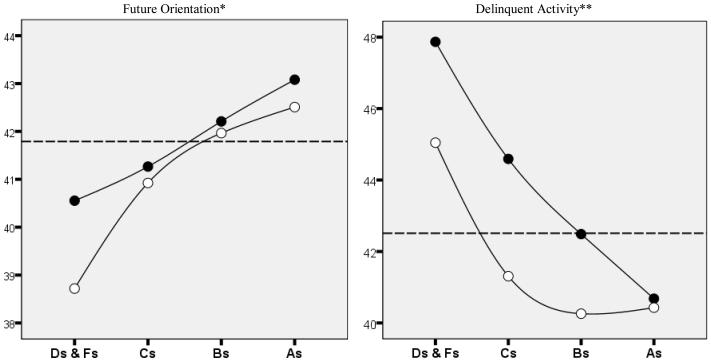

Figures 1a and 1b illustrate the linear relationship between two personal factors that evinced significant effects on pre-detention grades for Black and White youth detainees. Figure 1a demonstrates that youth who scored higher on the future orientation scale were more likely to report that they generally received A's and B's in school prior to detention. Conversely, youth admitting to more delinquent behaviors, were more likely to report receiving mostly D's and F's prior to detention. Black students were significantly more likely to report delinquent behaviors when compared to White students.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a & 1b: Relationship between Race (separate plots) and Grades Reported Prior to Detention (X Axis) on Personal Characteristics (Y Axes) among Adolescent Detainees.

Note. ● = Black adolescent detainees; ○ = White adolescent detainees. The dashed reference line on the Y-axis marks the estimated mean of the dependent variable. *Main effect for grades; **Main effects for grades and race.

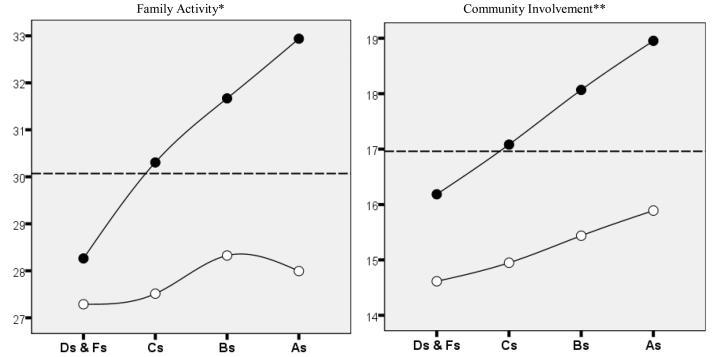

Figures 2a and 2b demonstrate that external resources, including family activities and community involvement, had a significant impact on grades, particularly among Black youth detainees. There was an interaction effect for family activities (F = 4.00, df = 1, p > 01), indicating that while family activity significantly improved grades for Black youth detainees, no such relationship existed among White youth detainees.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a & 2b: Relationship between Race (separate plots) and Grades Reported Prior to Detention (X Axis) on External Resources (Y Axes) among Adolescent Detainees.

Note. ● = Black adolescent detainees; ○ = White adolescent detainees. The dashed reference line on the Y-axis marks the estimated mean of the dependent variable. *Main and interaction effects for grades and race; **Main effects for grades and race.

Influences on Academic Potential across Gender

A second MANOVA was completed between Black male and Black female participants to explore gender differences in the Black youth detainees' levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy, future orientation, family and community involvement, depression, childhood trauma, and delinquent activity, and their respective relationships with academic

potential, as measured by their pre-detention grades and desire to return to school. Table 2 displays the means, standard deviations and F-ratios of factors that have a hypothesized relationship with academic potential among Black male and female youth detainees. When computing F-ratios for pre-detention grades only for the Black participants, all measures, except self-esteem and self-efficacy, had a significant relationship. Significant differences surfaced between Black male and female youth detainees for self-efficacy, depression, trauma and delinquency. Compared to Black females, Black males scored lower on measures of self-efficacy, depression, and trauma, and higher on the measure of delinquency.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and F Ratios of Factors Associated with Pre-detention Academic Achievement among Male and Female African American Detainees

| Grades before detention | F-Ratio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Gender | Below Avg. (M, SD) |

Avg. (M, SD) | Good (M, SD) | Very Good (M, SD) |

Total (M, SD) | Gender | Grades |

| Self-Esteem | Male | 26.13 (3.96) | 25.92 (3.74) | 26.63 (3.21) | 26.46 (3.36) | 26.41 (3.47) | 1.60 | 1.64 |

| Female | 25.52 (3.95) | 26.13 (2.97) | 26.26 (3.44) | 26.00 (3.86) | 26.03 (3.66) | |||

| Total | 25.78 (3.96) | 26.02 (3.37) | 26.43 (3.34) | 26.11 (3.75) | 26.18 (3.59) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Self-Efficacy | Male | 12.75 (3.47) | 12.41 (3.17) | 13.07 (3.36) | 13.64 (3.84) | 13.02 (3.45) | 19.36** | .27 |

| Female | 13.98 (3.89) | 14.92 (2.91) | 13.79 (3.52) | 13.50 (3.81) | 13.81 (3.66) | |||

| Total | 13.45 (3.76) | 13.65 (3.28) | 13.46 (3.46) | 13.53 (3.81) | 13.50 (3.60) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Future Orientation | Male | 39.87 (7.61) | 41.86 (7.41) | 41.37 (6.98) | 41.99 (7.26) | 41.25 (7.23) | 1.02 | 4.93* |

| Female | 40.38 (8.53) | 40.72 (6.31) | 42.74 (7.46) | 43.34 (7.91) | 42.38 (7.80) | |||

| Total | 40.16 (8.13) | 41.30 (6.88) | 42.11 (7.27) | 43.01 (7.76) | 41.93 (7.59) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Depression Scale | Male | 19.61 (6.14) | 17.51 (4.80) | 17.86 (5.53) | 18.17 (5.63) | 18.21 (5.61) | 76.59** | 4.86* |

| Female | 23.07 (6.32) | 21.69 (6.72) | 21.25 (5.99) | 21.31 (6.01) | 21.62 (6.14) | |||

| Total | 21.58 (6.46) | 19.56 (6.17) | 19.69 (6.02) | 20.54 (6.06) | 20.27 (6.17) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Family Involvement | Male | 27.45 (8.13) | 29.37 (7.13) | 30.88 (7.04) | 33.36 (6.53) | 30.45 (7.41) | .20 | 18.63** |

| Female | 27.84 (8.61) | 30.23 (7.79) | 31.71 (7.48) | 32.21 (8.41) | 31.10 (8.18) | |||

| Total | 27.67 (8.39) | 29.79 (7.45) | 31.33 (7.28) | 32.49 (7.99) | 30.84 (7.89) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Community Involvement |

Male | 15.74 (4.70) | 16.59 (4.18) | 17.69 (4.36) | 18.01 (4.72) | 17.22 (4.53) | .51 | 14.11** |

| Female | 15.70 (5.24) | 16.79 (4.51) | 17.91 (4.54) | 18.56 (5.03) | 17.67 (4.94) | |||

| Total | 15.71 (5.00) | 16.69 (4.33) | 17.81 (4.45) | 18.42 (4.95) | 17.49 (4.79) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Childhood Trauma | Male | 35.30 (12.10) | 34.48 (8.89) | 32.16 (8.04) | 31.32 (7.94) | 32.93 (9.16) | 30.57** | 4.19* |

| Female | 41.48 (18.50) | 38.11 (14.91) | 37.29 (15.37) | 37.49 (16.62) | 38.15 (16.40) | |||

| Total | 38.83 (16.32) | 36.27 (12.31) | 34.92 (12.78) | 35.98 (15.19) | 36.08 (14.20) | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Delinquent activity | Male | 51.93 (14.02) | 46.67 (12.46) | 45.39 (12.01) | 43.79 (13.73) | 46.56 (13.06) | 37.04** | 16.11** |

| Female | 45.75 (12.20) | 41.74 (8.95) | 41.33 (10.53) | 40.22 (8.62) | 41.72 (10.23) | |||

| Total | 48.41 (13.34) | 44.24 (11.11) | 43.20 (11.41) | 41.10 (10.21) | 43.64 (11.68) | |||

p < .01

p < .001

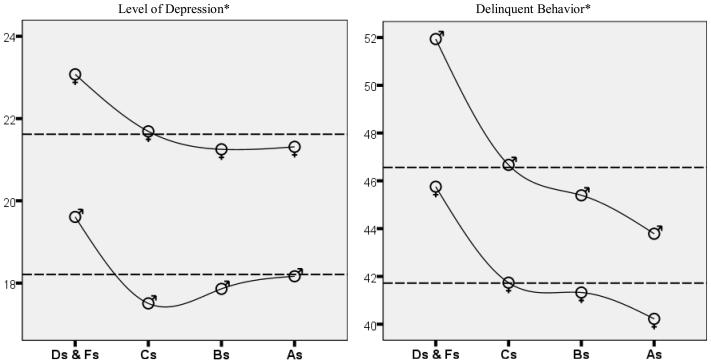

As demonstrated by Figures 3a and 3b, Black male and female youth detainees with higher levels of depression and delinquency were more likely to report receiving D's and F's in school. When looking at the mean score of their peers, represented by the dashed line across the Y-axes, for both depression and delinquency, youth detainees reporting D's and F's were significantly above the mean, whereas A and B students were at or below the mean. The graphs also show the stark differences between Black male and female scores on depression and delinquency.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a & 3b: Relationship between Gender (separate plots) and Grades Reported Prior to Detention (X Axis) on Personal Factors (Y Axes) among African American Adolescent Detainees.

Note. ♀= Female adolescent detainees; ♂= Male adolescent detainees. The dashed reference lines on the Y-axis through the respective interpolation lines marks the estimated means of the dependent variables for each gender. *Main effects for grades and gender.

Discussion

The results of this study provides clear evidence that potential exists for detained youth to reenter the school setting if their personal and emotional base is supported and they have adequate family and community resources. Over 90% of all detained youth indicated the desire to return to school, which suggest that the vast majority of youth detainees understand the importance of school. In spite of the natural disruptions that juvenile detention has on academic progress, more than half of the detained youth planned to pursue college and maintained lofty career aspirations.

Since only 10% of the participants indicated that they were not planning to return to school, self-reported grades prior to detention was used as the key indicator of academic potential. Findings revealed that youth were more likely to evince academic potential when they had a healthy level of self-esteem, adequate future goal orientation, positive mood, family and community involvement, fewer traumatic events, and less delinquent activity. Family and community involvement had a more pronounced effect on the academic potential of Black youth detainees.

The study also revealed some insights into gender differences between Black youth detainees with respect to academic potential. When compared to all other race-gender groups black female detainees were more likely to have plans to return to school after detention, a desire to attend college, reported the highest grades prior to detention, and had the most ambitious career aspirations. Other sources of resilience for Black female detainees appear related to their higher levels of self-efficacy and less delinquent activities when compared to Black males. Consistent with previous research (Kelly, et al., 2004; Nordness, et al., 2002), factors that appear to place Black female detainees at risk for not reaching their academic potential are related to their higher levels of measured depression and increased vulnerability to experiencing a traumatic event during childhood.

Black male detainees are also very likely to plan to return to school and well over half desire to eventually go to college or a vocational education program. Compared to black females, they enter detention with lower measured levels of depression and traumatic events; however they have less measured levels of self-efficacy. Black males also enter juvenile detention with more serious delinquent activity, which can diminish their academic potential. The findings also provide some evidence that Black males have difficulty assessing realistic career options. For example, the most frequently counted career aspiration for Black males was a professional athlete, followed by being uncertain. Like Black females, having a high level of family and community involvement greatly reinforced academic potential.

Implications for policy and practice

Juvenile justice policy should recognize the significant contribution of emotional wellbeing to the successful reentry to school for Black detainees. Policies that increase funding for detention counselors and social workers could help to improve the emotional wellbeing of detainees, particularly females who may enter with higher levels of depression and more traumatic experiences. Since community involvement and family are significantly linked to Black detainee's academic potential, greater emphasis should be placed on family counseling, loss and bereavement and community empowerment. In addition, pro-social skills training programs could reduce behaviors associated with delinquent acts among Black students.

Consistent with findings in previous studies (Jackson & Moore, 2006), the findings also reinforce the need for college access programs for Black detainees. With the large number of youth detainees who aspire to attend college, any policy that limits their access to federal Pell grants or other student aid because of their past failing is likely to reduce their level of motivation and academic potential (Tewksbury & Taylor, 1996).

Juvenile detention facilities should also increase attention to parent involvement in detainees' rehabilitative experiences. The explosion of the Black male inmate population has conceivably contributed to the overrepresentation of Black youth in detention centers. Practices that emphasize mentoring programs and other means to develop realistic career goals, particularly among Black males, are likely to also improve academic potential. Supplementing JDF-based education with community resources and academic assistance can also help to build character, which can elevate academic potential.

Limitations and Conclusions

There are several limitations that must be considered within the context of the findings. First, since data were collected about socially desirable attributes, some detainees may have used impression management during self-report procedures. Although all surveys were confidential, some respondents may have embellished grades or other information to present their abilities and achievements more favorably. In addition, the survey was lengthy and solicited information beyond this study's scope. Their length may have created some fatigue and led to “Yea-Saying” or “Nay-Saying” whereby respondents tend to select only the positive or negative answers on the survey. Finally, the special education status of participants were not identified prior to this study, therefore reported grades could have varying meanings across participants.

Overall, juvenile justice policies should be examined to reduce the frequency and burden of jail and detention center involvement among Black students. NCLB mandates for educational standards in juvenile detention centers should be followed to minimize academic distractions. In addition, the over-representation of black males in the juvenile justice system needs to be addressed by targeting biases in arrests and sentencing.

References

- Bailey CB. A qualitative study on the status of special education programs within juvenile detention facilities in Alabama. ProQuest Information & Learning; US: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D, Fink L. The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: a retrospective self-report. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Binder A, Geis G, Bruce D. Juvenile delinquency: historical, cultural, legal perspectives. Macmillian Publishing Company; New York, NY: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Robbins MJ. Serving the Special Education Needs of Students in Correctional Facilities. [Article] Exceptional Children. 1979;45(7):574–579. doi: 10.1177/001440297904500712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinkenbeard S, Navaratil C, Yost J, Hill JR, Roush DW. Education Services for Youth in Juvenile Detention Centers. [Report] Journal for Juvenile Justice & Detention Services. 1996;11(2):83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Conlon B, Harris S, Nagel J, Hillman M, Hanson R. Education: Don't Leave Prison Without It. [Article] Corrections Today. 2008;70(1):48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer Brooks C. The Challenge of Following Education Legislation in Confinement Education Programs. [Article] Corrections Today. 2008;70(1):28–46. [Google Scholar]

- David BL. Detention home teens as tutors: A cooperative cross-age tutoring pilot project. [Article] Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties. 2005;10(1):7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Drakeford W. The Impact of an Intensive Program to Increase the Literacy Skills of Youth Confined to Juvenile Corrections. [Article] Journal of Correctional Education. 2002;53(4):139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Drewry GH. Solving bad boy problem. [Article] Journal of Education. 1920;91(16):441–441. [Google Scholar]

- DuCloux K. Community College Education in a Juvenile Residential Treatment Facility: A Case Study of the Academic Achievement of Incarcerated Juveniles. [Article] Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2003;21(2):61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Edney HT. Black students still struggle in post-Brown era. New York Amsterdam News. 2004;95(22):37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Evans WP, Brown R, Killian E. Decision Making and Perceived Postdetention Success Among Incarcerated Youth. [Article] Crime & Delinquency. 2002;48(4):553. [Google Scholar]

- Francis JR. Developing and Implementing a Stress Management Program for Special Educators in a Juvenile Detention Center. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Giovanni EMSW. Perceived Needs and Interests of Juveniles Held in Preventive Detention. [Overview] Juvenile & Family Court Journal. 2002;53(2):51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Glick B, Sturgeon W. Rising to the Challenge: Identifying and Meeting the Needs of Juvenile Offenders With. [Article] Corrections Today. 1999;61(2):106. [Google Scholar]

- Griffinger W, Texeira SB. National Trends, Local Consequences: The Expansion of Juvenile Detention Facilities. [Research Materials] Youth Law News. 2001;22(1):18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg LK. The measurement of future time perspective. Vanderbilt University; Nashville, TN: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hellriegel KL, Yates JR. Collaboration between correctional and public school systems serving juvenile offenders: A case study. [Article] Education & Treatment of Children. 1999;22(1):55. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JFL, Moore JL. African American Males in Education: Endangered or Ignored? Teachers College Record. 2006;108(2):201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Keith JM, McCray AD. Juvenile offenders with special needs: critical issues and bleak outcomes. [Article] International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (QSE) 2002;15(6):691–710. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P, Martinez E, Medrano M. Gender-Specific Health Education in the Juvenile Justice System. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2004;11(1):45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Leone PE, Drakeford W, Meisel SM. Special Education Programs for Youth with Disabilities in Juvenile Corrections. [Article] Journal of Correctional Education. 2002;53(2):46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez JY. Character Education in Juvenile Detention. [Article] Corrections Today. 2008;70(2):150–154. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson PK. Providing mental health services in juvenile detention. [Educational Materials] Journal for Juvenile Justice & Detention Services. 1993;8(1):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison HR, Epps BD. Warehousing or Rehabilitation? Public Schooling in the Juvenile Justice System. Journal of Negro Education. 2002;71(3):218. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CM, Sprague JR, Jolivette K, Smith CR, Tobin TJ. Positive behavior support in alternative education, community-based mental health, and juvenile justice settings. In: Sailor W, Dunlop G, Sugai G, Horner R, editors. Handbook of positive behavior support. Springer Publishing Co; New York, NY US: 2009. pp. 465–496. [Google Scholar]

- Nordness PDMA, Grummert MMS, Banks D, Schindler ML, Moss MMMA, Gallagher K, et al. Screening the Mental Health Needs of Youths in Juvenile Detention. [Research Materials] Juvenile & Family Court Journal. 2002;53(2):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Painter RM. Job satisfaction levels of juvenile detention education faculties and the implementation of best teaching practices compared to overall program efficacy. ProQuest Information & Learning; US: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Roush D. Content and Process of Detention Education. Journal of Offender Counseling Services and Rehabilitation. 1983;7(3-4):21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rozie-Battle JL. African American Teens and the Neo-Juvenile Justice System. Journal of Health & Social Policy. 2002;15(2):69–79. doi: 10.1300/J045v15n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarri RC, Shook JJ. The future for social work in juvenile and adult criminal justice. [Article] Advances in Social Work. 2005;6(1):210–220. [Google Scholar]

- Smith L. Behavioral and Emotional Characteristics of Children In Detention. [Article] Journal of Correctional Education. 1998;49(2):63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tewksbury R, Taylor JM. The consequences of eliminating Pell Grant eligibility for students in post-secondary. [Article] Federal Probation. 1996;60(3):60. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine VL. Crisis in the Classroom. Crisis (The New) 2005:2–2. Retrieved from http://search.epnet.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&an=18155038.

- Wiggan G. Race, School Achievement, and Educational Inequality: Toward a Student-Based Inquiry Perspective. Review of Educational Research. 2007;77(3):310–333. [Google Scholar]