Abstract

The presynaptic protein α-synuclein (αSyn) has been implicated in both familial and sporadic forms of Parkinson’s disease. We examined whether human αSyn-overexpressing mice under Thy1 promoter (Thy1-αSyn) display alterations of colonic function. Basal fecal output was decreased in Thy1-αSyn mice fed ad libitum. Fasted/refed Thy1-αSyn mice had a slower distal colonic transit than the wild-type mice, as monitored by 2.2-fold increase in time to expel an intracolonic bead and 2.9-fold higher colonic fecal content. By contrast, Thy1-αSyn mice had an increased fecal response to novelty stress and corticotropin releasing factor injected intraperipherally. These results indicate that Thy1-αSyn mice display altered basal and stress-stimulated propulsive colonic motility and will be a useful model to study gut dysfunction associated with Parkinson’s disease.

Keywords: α-synuclein, colonic motility, corticotropin releasing factor, mouse, Parkinson’s disease, stress

Introduction

Constipation is a common feature of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and can be manifested earlier than the motor disorder [1]. To date, there is very little known on colonic motor alterations in animal models of PD mainly owing to the lack of suitable models. Most recently, the selective dopamine neuron toxin 1-methyl 4-phenyl 1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) was used to reduce dopamine in the enteric nervous system [2]. However, it is not clear whether this toxin-induced animal model of PD reproduces the pathology causing gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction in PD patients, as the MPTP-treated mice showed a transient increase in colonic motility, and no change thereafter, rather than the expected decrease [2].

Accumulation of vesicular protein α-synuclein (αSyn) is a major component of Lewy bodies, which have been implicated in both sporadic and familial forms of PD [3]. αSyn inclusions occur in human brain and peripheral neurons involved in GI function, such as the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and enteric nervous system [4]. Therefore, we have investigated basal and postprandial colonic propulsive motor function in transgenic mice over-expressing αSyn under the Thy1 promoter (Thy1-αSyn) [5]. In addition, these transgenic mice do not lose dopaminergic neurons up to 18 months of age suggesting that they may provide a useful model of the ‘premanifest’ phase of PD, as dopamine cell loss may be preceded by a period of αSyn accumulation [6]. Stress and peripheral injection of the stress hormone, corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), are well established to stimulate colonic motility and defecation through activation of peristaltic enteric reflex in rodents [7]. To gain indirect insight to colonic myenteric responsiveness in mice overexpressing αSyn, we investigated the effects of novel environment and exogenous administration of CRF on propulsive colonic motility.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animal care was conducted in accordance with the United States Public Health Service Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the animal components were approved by UCLA Committee for Animal Use and Care. Thy1-αSyn mice overexpressing human wild-type (WT) αSyn under the membrane glycoprotein Thy1 promoter were generated as explained previously [5]. They were crossed into a mixed C57BL/6-DBA/2 background and maintained on this background by mating N5 female hemizygous mice for the transgene with male WT mice [8]. Genotype of mice was verified by PCR and amplification analysis of tail DNA. Male Thy1-αSyn mice [body weight: (BW) 29.4 ± 1.4 g, n=8] and their male littermate WT controls (BW: 41.1 ± 1.9 g, n=12; P<0.05) from seven litters were 11–12 months at the time of experiments. To conserve animals, mice were previously a part of behavioral studies that included treatment with dopamine agonists approximately 4–6 months before this study [8]. However, this should not be considered a confounding issue because of the long washout period. All mice were individually housed with free access to water and standard rodent chow and were maintained under controlled temperature and humidity on a reverse 12 h light/dark cycle (10.00–22.00 off/on) until the experiment began. All the experiments were performed in the dark cycle in mice fed ad libitum, unless otherwise stated.

Experimental design

Distal colonic transit and colonic fecal content in fasted/refed α-synuclein under the Thy1 promoter and wild-type mice

The method was similar as in our previous studies [9]. Thy1-αSyn and WT mice were fasted for 16–18 h with water ad libitum, and then refed for 1 h with preweighed food (standard rodent chow). Thereafter, mice were briefly anesthetized with isoflurane to insert a glass bead (2 mm diameter) into the distal colon 2 cm from the anus. Colonic transit was determined by monitoring the time at which the bead was expelled (bead latency). At 2 h after the bead insertion, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and the number of pellets in the colon was assessed. The 1-h food ingestion was calculated as the difference between the preweighed and remaining food and spill at the end of the 1-h feeding period.

Defecation in α-synuclein under the Thy1 promoter and wild-type mice exposed or accustomed to a novel environment and injected intraperitoneally with corticotropin releasing factor

Thy1-αSyn and WT mice were moved into a lighted room and placed in a new empty cage without food and water for 1 h. Pellet output was monitored at 5, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min thereafter. For the CRF experiments, Thy1-αSyn and WT mice were briefly handled and maintained on different bedding material (filter paper) for 2 h every day for 3 days to acclimate them to the experimental conditions. Thy1-αSyn and WT mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p., 0.1 ml/ mouse) either with rat/human CRF (20 μg/kg, Peptide Biology Labs, Salk Institute, La Jolla, California, USA) or saline. Immediately after the injection, each mouse was placed in a new cage with filter paper at the bottom of the cage and had no access to food and water. Fecal pellet output was monitored at 15-min intervals for 1 h.

Data expression and statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Fecal pellet output or inside the colon are corrected to a standard BW (20 g) owing to the significant difference between Thy1-αSyn and WT mice at the age of 11–12 months. Comparisons between two groups were performed using a Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney’s U-test when appropriate. Analysis of variance with Tukey post-hoc multiple comparisons was used to compare multiple independent variables. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

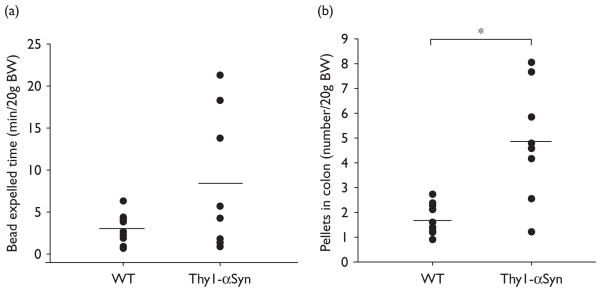

The time at which the glass bead was expelled after being inserted 2 cm into the distal colon at the end of 1-h refeeding period was not statistically longer in Thy1-αSyn than WT mice (8.4 ± 2.9 min/20 g BW, n=8 vs. 3.0 ± 0.5 min/20 g BW, n=11; P>0.05). However, scores of Thy1-αSyn mice were significantly more variable compared with scores of WT mice [F(7,10) =23.29, P<0.001], which resulted mainly from three of eight (38%) transgenic mice having slow distal colonic transit (17.8 ± 2.2 min/20 g BW) (Fig. 1a). The number of pellets contained in the colon monitored at 2 h after the refeeding period was significantly higher in 75% of fasted/refed Thy1-αSyn mice than in the WT mice (5.9 ± 0.7 pellets/20 g BW, n=6 vs. WT: 1.7 ± 0.2 pellets/20 g BW, n=12; P<0.05, Fig. 1b), resulting in overall group significance (transgenic: 4.9 ± 0.8 pellets/20 g BW, n=8 vs. WT: 1.7 ± 0.2 pellets/20 g BW, n=12; P<0.05). The Thy1-αSyn mice with more pellets contained in the colon had significant higher food intake than the WT mice (0.28 ± 0.05 g/20 g BW, n=6, vs. 0.16 ± 0.02 g/20 g, n=12; P<0.05), which was similar to that by the whole transgenic group (0.30 ± 0.05 g/20 g BW, n=8; P<0.05 vs. WT).

Fig. 1.

Colonic transit time of a glass bead inserted 2 cm into the distal colon of fasted/refed Thy1-αSyn and WT mice (a), and pellets remaining in the colon when the same groups of mice were euthanized 2 h after bead insertion (b). Points are individual values and lines represent the mean of 11 WT and 8 Thy1-αSyn mice. *P<0.05 compared with WT. BW, body weight; Thy1-αSyn, α-synuclein under the Thy1 promoter; WT, wild-type.

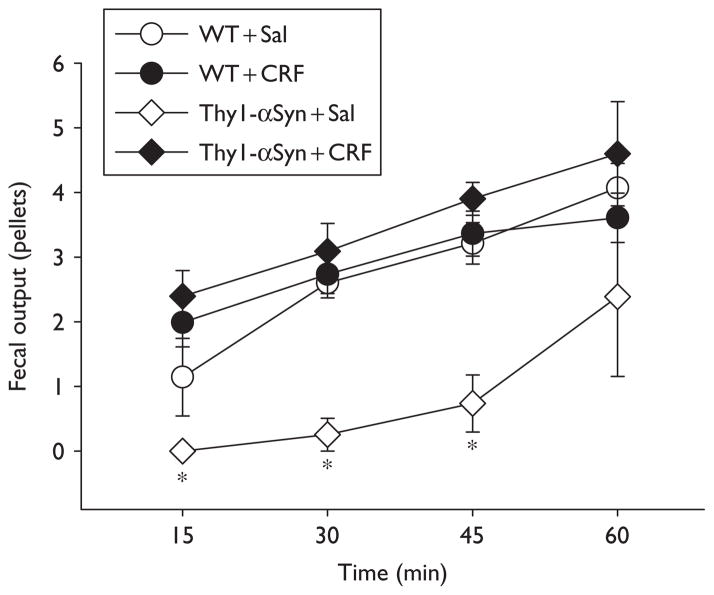

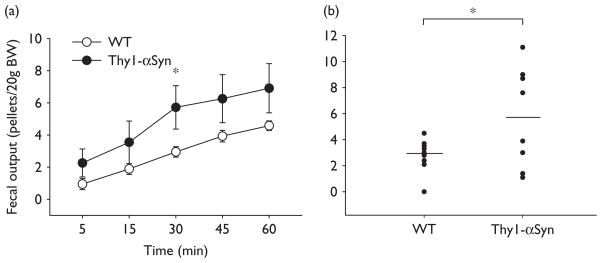

Thy1-αSyn mice acclimated to the experimental conditions injected with saline i.p. had significantly less basal pellet output than WT throughout the first 45 min as monitored every 15 min (45 min:0.7 ± 0.4 pellet number/ 20 g, n=3 vs. 3.2 ± 0.3 pellet number/20 g BW, n=5; Fig. 2). In Thy1-αSyn mice, CRF (20 μg/kg, i.p.) induced a significant peak increase in pellet output within 15 min compared with saline (2.4 ± 0.4 pellets/20 g BW, n=5 vs. 0.0 ± 0.0 pellets/ 20 g BW, n=3; P<0.05), whereas in WT mice, changes did not reach significance (15 min: CRF: 2.0 ± 0.4 pellets/20 g BW, n=6; vs. saline: 1.1 ± 0.6 pellets/20 g BW, n=5) (Fig. 2). In Thy1-αSyn mice exposed for 1 h to novel environment, 50% of mice defecated more pellets than WT mice throughout the experimental period with a peak response at 30 min (30 min: 9.1 ± 0.7 pellets/20 g BW, n=4 vs. WT: 3.0 ± 0.3 pellets/20 g BW, n=12; P<0.05), with all the Thy1-αSyn mice together still resulting in a significant increased colonic transit (30 min: 5.7 ± 1.4 pellets/20 g BW, n=8; P<0.05 vs. WT; Fig. 3b).

Fig. 2.

Time course of fecal pellet output in response to intraperitoneal injection of CRF in Thy1-αSyn and WT mice. Both groups of mice, trained to the experimental conditions, were injected intraperitoneally with saline (Sal, 0.1 ml/mouse) or CRF (20 μg/kg), and fecal output was monitored every 15 min for 1 h. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of cumulative fecal output over 1 h; WT + Sal: n=5, WT + CRF: n=6, Thy1-αSyn + Sal: n=3, and Thy1-αSyn + Sal: n=5 mice/group; *P<0.05 compared with other groups. CRF, corticotropin releasing factor;Thy1-αSyn, α-synuclein under the Thy1 promoter; WT, wild-type.

Fig. 3.

Propulsive colonic motor response to a novel environment exposure in Thy1-αSyn and WT mice. Animals were placed in a novel environment and defecation was monitored every15 min for 1 h. (a) Time course of cumulative fecal output over 1 h; each point represents the mean ± SEM of n=12/WTand n=8/Thy1-αSyn mice; *P<0.05 compared with WT. (b) Individual values of 30 min fecal output reflecting responders and nonresponders in Thy1-αSyn mice. Lines represent the means; *P<0.05 compared with WT. Thy1-αSyn, α-synuclein under the Thy1 promoter; WT, wild-type.

Discussion

αSyn overexpression has been used to generate cellular and animal models of PD [6,10]. These genetic models have been largely investigated in relation with the pattern of αSyn neuronal expression and behavioral deficits [10,11]. In particular, the Thy1-αSyn-overexpressing mice display a variety of progressive sensorimotor impairments and olfactory deficits at an early age [8,12]. However, whether these mice also recapitulate other recognized nonmotor symptoms associated with PD [13] is not known. Among those, constipation commonly occurs in over 50% of PD patients [1,14,15]. In our study, we show that 75% of Thy1-αSyn mice display a 3.5-fold higher number of pellets within their colon 2 h postprandially compared with WT litter-mates. Such retention of colonic stools in Thy1-αSyn mice is most likely unrelated to the increased food ingestion because the magnitude of food intake (1.8-fold) and colonic content (3.5-fold) were different, and the 2-h post feeding period would not allow all the ingested food to be converted into pellets into the colon. Thy1-αSyn-overexpressing mice also display a significantly variable distal colonic transit time with 38% of animals having transit times longer than 20 min, suggesting that colonic motility alterations must also take place within the proximal to the distal colon, to account for the increased storage of colonic pellets in 75% of transgenic mice. Likewise, in humans, slowing of large bowel transit time has been reported in a number of patients with PD along with colonic motility abnormalities [14,16]. Thy1-αSyn-overexpressing mice when placed in familiar conditions also displayed a reduced basal fecal output compared with WT mice. Notably, these studies were performed in 11–12-month-old male transgenic mice in keeping with epidemiological studies showing a much higher incidence of PD in men that rapidly increases with age [17]. Recent studies show that mice overexpressing human WT αSyn exhibit substantial sex-based differences in gene expression involved in transcriptional regulation that occurred more prominently after 9 months [18]. These data show in a genetic model of PD that 38–75% of Thy1-αSyn-overexpressing mice display alterations in propulsive colonic motor activity reminiscent of colonic dysmotility/ constipation associated with PD. Thy1-αSyn-overexpressing mice have been characterized as an animal model of early stages of the disease [6]. The present results indicate that this model also shows features of PD associated colonic dysfunction, as constipation is manifested earlier than the cardinal motor impairments and is predictive of future risk in developing PD [1]. These findings broaden the nonmotor phenotype of Thy1-αSyn-overexpressing mice to include GI dysfunction in addition to previously described olfactory deficits [12], another common early nonmotor symptom of PD [13]. The present data contrast with a chemical animal model of Parkinsonism in which no change in stool frequency and GI transit was observed in MPTP-treated male mice, which had a 40% reduction in the density of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive enteric neurons [2]. Such a difference may have a bearing with the limitation of chemical models that focus on targeting dopamine neurons and do not recapitulate the broad constellation of nonmotor impairments affecting PD patients [6].

The mechanisms through which αSyn overexpression impairs colonic propulsive motor function in a proportion of mice are still to be characterized. αSyn is a protein involved in presynaptic function, including vesicle handling and neurotransmitter release [19], and is one of the major components of Lewy bodies [3]. Immunohistological studies in human colonic tissues from patients with PD reveal that Lewy bodies are rarely observed in tyrosine hydroxylase myenteric neurons in the colon [20,21]. These observations along with the recent report that MPTP-treated mice do not show alterations in GI transit or defecation [2] provide convergent evidence that the mechanism may not be related to the loss/dysfunction of enteric dopaminergic neurons. Alternatively, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) enteric pathway may be involved, as most Lewy bodies in the gut occur in VIP neuronal cell bodies and processes [20,21]. In addition, mice with a targeted mutation in the gene encoding VIP display reduced basal intestinal transit and increased defecation to an environmental stress [22], as found in the Thy1-αSyn mice. However, it cannot be ruled out that the differential enhanced response during stress in transgenic mice relates to alterations in the central nervous system regulating the colonic motor stimulation. In Thy1-αSyn mice, αSyn is widespread throughout the brain including the locus coeruleus [4], which is an established site of action for stress to alter colonic motor function through autonomic pathways [7]. However, colonic stimulation induced by CRF i.p. is mediated by a direct activation of colonic myenteric excitatory cholinergic and inhibitory nitric oxide and VIP neurons [23] involved in the peristaltic reflex [24]. The increased propulsive response to CRF i.p. in Thy1-αSyn mice may be consistent with a decrease in VIP inhibitory tone at the myenteric level and support that cholinergic neurons are responsive to CRF.

In conclusion, this study shows that 75% of Thy1-αSyn-overexpressing male mice display intracolonic retention of feces postprandially and low basal defecation scores compared with WT. This provides the first experimental model with colonic motor function impairments, reminiscent of the constipation commonly observed in over 50% of PD patients. The mechanisms involved remain to be established, but may include, in part, alterations in VIP enteric neurons. This is on the basis of VIP enteric neurons being the target of Lewy body accumulation in human tissues of PD patients and a failure of the dopaminergic neurotoxin model of PD to show altered colonic fecal expulsion in the presence of a defect in dopaminergic enteric neurons. The Thy1-αSyn mice also show increased colonic response to stress, which is partially resulted from dysfunctional colonic motility.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Jean Rivier (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA) for the generous supply of CRF and Mrs Honghui Liang for her technical support. This work was funded by Morris K. Udall PD Research Center of Excellence at UCLA (P50NS38367), American Parkinson Disease Association, and the Chen Family, Center grant NIHDDK 41301 (Animal Core), RO1 DK 57238 and VA Career Scientist Award.

References

- 1.Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, White LR, Masaki KH, Tanner CM, Curb JD, et al. Frequency of bowel movements and the future risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2001;57:456–462. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson G, Noorian AR, Taylor G, Anitha M, Bernhard D, Srinivasan S, et al. Loss of enteric dopaminergic neurons and associated changes in colon motility in an MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2007;207:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tofaris GK, Spillantini MG. Physiological and pathological properties of alpha-synuclein. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2194–2201. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockenstein E, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, Song D, Shults CW, Lang I, et al. Differential neuropathological alterations in transgenic mice expressing alpha-synuclein from the platelet-derived growth factor and Thy-1 promoters. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68:568–578. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chesselet MF. In vivo alpha-synuclein overexpression in rodents: a useful model of Parkinson’s disease? Exp Neurol. 2008;209:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tache Y, Bonaz B. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors and stress-related alterations of gut motor function. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:33–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI30085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming SM, Salcedo J, Hutson CB, Rockenstein E, Masliah E, Levine MS, et al. Behavioral effects of dopaminergic agonists in transgenic mice overexpressing human wildtype alpha-synuclein. Neuroscience. 2006;142:1245–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez V, Wang L, Rivier J, Grigoriadis D, Tache Y. Central CRF, urocortins and stress increase colonic transit via CRF1 receptors while activation of CRF2 receptors delays gastric transit in mice. J Physiol. 2004;556:221–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maries E, Dass B, Collier TJ, Kordower JH, Steece-Collier K. The role of alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease: insights from animal models. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:727–738. doi: 10.1038/nrn1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming SM, Chesselet MF. Behavioral phenotypes and pharmacology in genetic mouse models of Parkinsonism. Behav Pharmacol. 2006;17:383–391. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleming SM, Fernagut PO, Chesselet MF. Genetic mouse models of parkinsonism: strengths and limitations. NeuroRx. 2005;2:495–503. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziemssen T, Reichmann H. Non-motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards LL, Quigley EM, Pfeiffer RF. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: frequency and pathophysiology. Neurology. 1992;42 :726–732. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrne KG, Pfeiffer R, Quigley EM. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: a report of clinical experience at a single center. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:11–16. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakakibara R, Odaka T, Uchiyama T, Asahina M, Yamaguchi K, Yamaguchi T, et al. Colonic transit time and rectoanal videomanometry in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:268–272. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Den Eeden SK, Tanner CM, Bernstein AL, Fross RD, Leimpeter A, Bloch DA, et al. Incidence of Parkinson’s disease: variation by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:1015–1022. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yacoubian TA, Cantuti-Castelvetri I, Bouzou B, Asteris G, McLean PJ, Hyman BT, et al. Transcriptional dysregulation in a transgenic model of Parkinson disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29:515–518. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yavich L, Tanila H, Vepsalainen S, Jakala P. Role of alpha-synuclein in presynaptic dopamine recruitment. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11165–11170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2559-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Ohama E, Ikuta F. Parkinson’s disease: an immunohistochemical study of Lewy body-containing neurons in the enteric nervous system. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1990;79:581–583. doi: 10.1007/BF00294234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singaram C, Ashraf W, Gaumnitz EA, Torbey C, Sengupta A, Pfeiffer R, et al. Dopaminergic defect of enteric nervous system in Parkinson’s disease patients with chronic constipation. Lancet. 1995;346:861–864. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lelievre V, Favrais G, Abad C, Adle-Biassette H, Lu Y, Germano PM, et al. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in mice with a targeted mutation in the gene encoding vasoactive intestinal polypeptide: a model for the study of intestinal ileus and Hirschsprung’s disease. Peptides. 2007;28:1688–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan PQ, Million M, Wu SV, Rivier J, Tache Y. Peripheral corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) and a novel CRF1 receptor agonist, stressin1-A activate CRF1 receptor expressing cholinergic and nitrergic myenteric neurons selectively in the colon of conscious rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:923–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi XZ, Choudhury BK, Pasricha PJ, Sarna SK. A novel role of VIP in colonic motility function: induction of excitation-transcription coupling in smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1388–1400. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]