Abstract

Ecstasy (MDMA) use raises concerns because of its association with risky driving. We evaluated driving performance and risk taking in abstinent recreational MDMA users in a simulated car following task that required continuous attention and vigilance. Drivers were asked to follow two car lengths behind a lead vehicle (LV). Three sinusoids generated unpredictable LV velocity changes. Drivers could mitigate risk by following further behind the erratic LV. From vehicle trajectory data we performed a Fourier analysis to derive measures of coherence, gain, and delay. These measures and headway distance were compared between the different groups. All MDMA drivers met coherence criteria indicating cooperation in the car following task. They matched periodic changes in LV velocity similar to controls (abstinent THC users, abstinent alcohol users, and non-drug users), militating against worse vigilance. While all participants traveled approximately 55mph (89kph), the MDMA drivers followed 64m closer to the LV and demonstrated 1.04s shorter delays to LV velocity changes than other driver groups. The simulated car following task safely discriminated between driving behavior in abstinent MDMA users and controls. Abstinent MDMA users do not perform worse than controls, but may assume extra risk. The control theory framework used in this study revealed behaviors that might not otherwise be evident.

Keywords: Car following, Fourier analysis, Coherence, Ecstasy (MDMA)

1. Introduction

Ecstasy or MDMA (± 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine) is a popular psychoactive substance used by young people for its sociability enhancing and energy boosting effects. MDMA is chemically related to amphetamine and mescaline (de Man, 1994; Morgan, 2000). Persistent (Krystal et al., 1992; McCann et al., 1999; Morgan, 1999; Gouzoulis Mayfrank et al., 2000; Verkes et al., 2001) and heavy MDMA use (Bolla et al., 1998; Parrott et al., 1998; Parrott, 2001) may impair memory. Even abstinent MDMA users may have persistent impairments on sustained and divided attention, semantic recognition, verbal reasoning and learning tasks (Parrott and Lasky, 1998; Parrott et al., 1998; McCann et al., 1999; Gouzoulis Mayfrank et al., 2000; Parrott, 2001). Impairments of episodic memory, working memory and attention, and elevated impulsiveness and hostility may persist for at least 6 months after abstaining from chronic, heavy, recreational MDMA use (Morgan, 2000).

Widespread ecstasy use by young people raises major concerns, particularly because of its association with risky driving and car crashes (Henry et al., 1992). Epidemiological research and case studies have shown that impaired judgment and higher risk taking are likely factors in methamphetamine-related traffic crashes (Schifano, 1995; Logan and Couper, 2001). While screening for MDMA is not routine in crash investigations, MDMA may cause unsafe driving because of impairment of movement estimation, coordination, and concentration (Rizzo et al., 2005, Lamers et al.,2006a). An ongoing research debate concerns whether even rare MDMA use may produce lasting cognitive impairments due to damage in neural mechanisms underlying judgment, decision-making, and other executive functions (Parrott, 2001). This impacts not only driving behavior but also many other facets of life.

Repeated MDMA use causes serotonergic neurotoxicity in laboratory animals, and may result in long-term damage in humans. Abstinent MDMA users display reduced levels of 5-HT, 5-HIAA, tryptophan hydroxylase and serotonin transporter density associated with functional deficits in learning, memory, and other higher cognitive processes (Parrott, 2001), particularly in heavy users. These deficits probably reflect serotonergic axonal loss in higher brain regions, especially the frontal lobes and the hippocampus. Psychopharmacological studies support a key role for serotonin in decision-making (Bechara, 2003), suggesting that serotonin axonal loss can impair judgment and decision-making. These problems seem to persist long after recreational ecstasy use has ceased, suggesting long lasting or permanent damage.

Several studies suggest that MDMA has task specific effects on driving. Raemakers et al. (2006) examined effects of ingestion and withdrawal from MDMA and methylphenidate. MDMA improved real world lane tracking performance, but degraded car following performance. Drivers who ingested MDMA overreacted to lead vehicle (LV) velocity changes during the car following task. The effects were not evident after withdrawal from MDMA. Kuypers et al. (2006) studied combined effects of alcohol and MDMA. MDMA improved lane tracking but degraded car following performance, in line with Raemakers et al. (2006). Drivers using MDMA and alcohol performed better on the real world lane tracking task than drivers who used alcohol alone.

Brookhuis et al (2004) examined the effects of MDMA alone and combined with other drugs on simulated car following, gap acceptance, and braking scenarios. Drivers in the multidrug condition accepted smaller gaps and showed greater SDLP compared to MDMA alone and no drug conditions. However, drivers in the MDMA and multidrug conditions showed higher and more variable speeds and had more crashes.

This study used driving simulation to evaluate the potential link between recreational MDMA use, executive function (i.e., decision-making, impulse control, risk acceptance) and driver behavior. To do so, we evaluated performance and risk taking of abstinent recreational MDMA users and control participants using a simulated car following scenario. The scenario was based on the pioneering work of Brookhuis et al. (1994) and Andersen and Ni (2005), with modifications, and evaluated driver willingness and ability to follow closely behind a LV that erratically varied its velocity.

Our implementation asked drivers to follow two car lengths behind the LV at freeway speeds at a time headway of approximately 0.5 s, a difficult and inherently dangerous task that could only be implemented safely in a driving simulator. The scenario poses challenges similar to driving in traffic on a freeway. Yet, because there was no traffic pressuring the driver from behind, the driver could choose to mitigate risk by following the LV less closely. The simulator scenario posed challenges that are highly relevant to MDMA use, because performing this task requires continuous attention and vigilance to the LV as well as evaluation and management of personal risk.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

We evaluated driving performance on a car following task in four groups of drivers: abstinent MDMA users, abstinent THC users, abstinent alcohol users, and non-drug using controls. The purpose of the non-MDMA groups was to control for other drug use, because most people who use MDMA also use other drugs (Parrott, 2001), particularly THC and alcohol.

Participants were recruited by advertisement, approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board (IRB). Drug screens were administered to determine eligibility to participate, including a urine screen for drug use, a Breathalyzer screen for alcohol use, and an exhaled CO screen for tobacco use. At the time of the study, non-drug users were required to have abstained from all drugs for 12 months. All participants were required to abstain from substances for 48 hours before the scheduled visit. Subjects in the user groups who failed to pass all three screening tests were invited to reschedule their appointment.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria were as follows:

MDMA poly substance users

These individuals used MDMA > 10 times in the last three years, and may have used THC > 10 times. They may have occasionally used other drugs beside MDMA and THC, but no more than 30 times in their lifetime. The amount of other drug use could not exceed that in which MDMA was used. For example, someone who used MDMA 20 times, but used LSD 30 times, or cocaine 40 times was excluded.

THC poly substance users

These individuals used THC no more than 10 times in the last three years, but never used MDMA. Other drug use was at most 30 times in their lifetime and did not exceed the number of times they used THC.

Alcohol users

These individuals never used MDMA. They may have tried THC or other drugs, but only a few times (< 6 times) in their lifetime. Alcohol use in this group was > 10 alcoholic drinks per week. To control for tobacco use, we attempted to recruit equal number of participants who used alcohol and tobacco (> 20 cigarettes per week) and who did not use tobacco those who only used alcohol (< 1 cigarette per week).

Non-drug users

These individuals were similar to the alcohol users with respect to MDMA, THC or other drug use. The last time they used any drug (except alcohol or nicotine) was at least 12 months prior to the study. The alcohol use in this group was less than 5 alcoholic drinks per week.

Table 1 provides the age and gender breakdown for each group as well as the number of participants. Age differed between the four groups, with the abstinent MDMA and abstinent THC users coming from a younger population (p=0.0044). The distribution of gender was not significantly different across groups (p=0.1214) but there were more males in the abstinent MDMA group and in the abstinent THC group.

Table 1.

Age and Gender Distributions

| MDMA | THC | ALC | NODRUG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean (sd) | 23.44 (1.50) | 23.32 (5.78) | 25.42 (5.63) | 28.35 (7.75) |

| Female | 5 | 9 | 12 | 17 |

| Male | 11 | 30 | 12 | 23 |

| N | 16 | 39 | 24 | 40 |

2.2 Simulated Driving Performance

All participants completed a simulated drive in SIREN (Simulator for Research in Ergonomics and Neuroscience), an interactive driving simulator that creates an immersive, real-time virtual environment for assessing at-risk drivers in a medical setting (Rizzo et al., 2005). SIREN comprises a 1994 GM Saturn with the running gear removed, embedded electronic sensors, and miniature cameras for recording driver performance, a sound system and surrounding screens (150° forward field of view (FOV), 50° rear FOV), four LCD projectors with image generators, and computers for scenario design, control, and data collection. All street signs and road scenarios conform to the requirements of AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) and MUTCD (Manual for Uniform Traffic Control Devices). Prior to beginning the experiment, a 5 to 10 minute “warm-up and training” session was held to familiarize drivers with the vehicle controls. Afterward, drivers completed a brief checklist of vehicle knowledge and operations to assure a level of proficiency sufficient to proceed with the experiment (McGehee et al, 2004).

2.3 Car Following Task

Table 2 outlines the car following task in a standard format suggested by the Simulator Users Group (http://www.simusers.com/tiki-index.php, accessed 2/4/09). Drivers in SIREN were instructed to follow approximately two car lengths behind a LV (see Figure 1).

Table 2.

Car Following Scenario

| Scenario | Car Following |

|---|---|

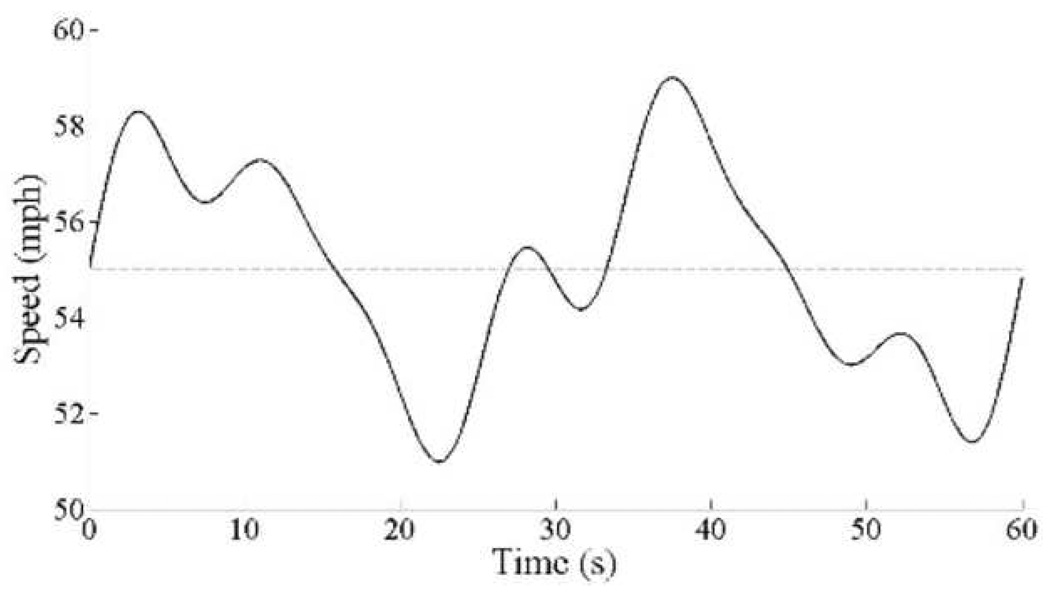

| Description | Lead Vehicle (LV) velocity was programmed to vary velocity following a pattern created by the sum of three sine waves (Andersen and Ni, 2005). The scenario started with the LV located two car lengths in front of the participant vehicle. As the participant accelerated to the speed limit (55 mph) the LV maintained a headway distance of 18 meters. After 500 meters, the LV began to modulate its velocity according to a sum of sines function. Three sinusoids were used to create the LVs seemingly unpredictable behavior. The amplitudes of the three sinusoids were 6.072 (9.722), 2.417 (3.889), and 1.726 (2.778) mph (kph). The corresponding frequencies were 0.033, 0.083, and 0.117 Hz. The phase for each sinusoid differed. The phase for the high and middle frequency sinusoids were randomly assigned a value between 0 and 1. The low frequency sinusoid was then assigned a value that caused the sum of the three sinusoids to be zero on the first frame, thereby ensuring that the LV always started the task at a velocity of 55 mph. The random phase values caused the LVs velocity pattern to be different for each participant. Figure 2 depicts how the sum of sine function would influence the LVs velocity over the course of a minute. |

| Participant Instructions | The driver is instructed to follow at a distance of two car lengths behind the LV. |

| Measures of interest | Cognitive constructs stressed: Attention, perception, vigilance, continuous visuomotor performance and risk acceptance/ risk taking. |

Dependent driving variables: Following distance (mean, SD); coherence, gain, and delay calculated using Fourier analysis (Brookhuis et al., 1994; Janacek, 2008)

|

|

| Data Reduction / Variable Calculation | Following distance and velocity were recorded at 60 Hz. A Fourier analysis was performed using the velocities of the LV and the participant vehicle to obtain coherence, gain and delay. The values for gain, coherence, and delay were obtained for the frequency with the highest spectral density for the LV. |

| Implementation Variations | The task may be modified by giving the driver external instructions or changing speed parameters, thereby altering driver workload and risk level. For instance, variations can be made on this script: the driver could be asked to follow as closely behind the LV as possible, or to follow comfortably behind as possible, or the speed limit could be lower or higher than 55 mph. A following car could be added to “box in” and pressure the driver to follow the LV more closely. |

| Measurement Challenges | Some drivers may not perform the task as instructed. For instance, they may adopt a large headway. While this may reflect a strategy by the participant, it complicates interpretation of the primary measures. The longer the task is performed, the more stable the measures derived from the Fourier analysis are. |

| Validity | The scenario may not characterize how drivers perform car following in the real world. An instrumented vehicle could be used to study car following behavior on the road, particularly in league with a confederate experimental LV, however the environmental variables could not be easily controlled and the safety risk could be unacceptable. |

| Useful References |

|

Figure 1.

Static frame from the simulator depicts the view available to the driver at a distance of approximately 18 meters behind the LV for the car following task.

3. Analysis

3.1. Data Reduction / Variable Calculation

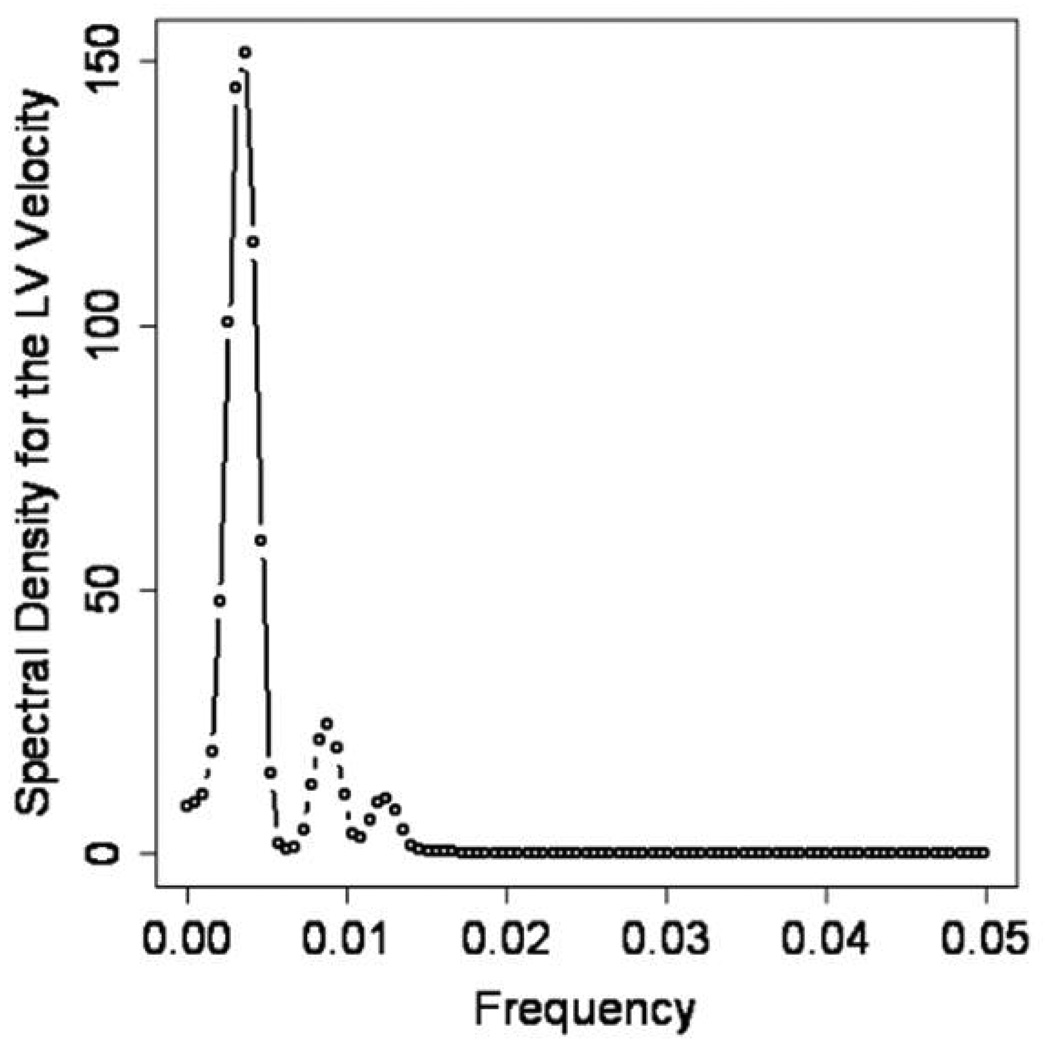

A finite Fourier transform was performed using the velocity of the LV and the subject vehicle throughout the car following task as proposed by Brookhuis et al. (1994). A Tukey-Hanning procedure was used to smooth the data and to ensure the estimations were consistent (Janacek, 2008). The transform outputs four measures 1) spectral density of the LV’s velocity, 2) spectral density of the subject vehicle’s velocity, 3) coherence, and 4) phase for n/2 frequencies between 0 and pi. Table 3 provides an example of the Fourier transform output. Spectral density is used in Fourier analysis to determine the frequencies at which periodic changes occur (Janacek, 2008). The other output values (coherence, and phase, as well as gain — which is calculated as the ratio spectral density of the subject vehicle’s velocity / spectral density of the LV’s velocity) characterize how well the participant responds to changes in the LV velocity profile (see Table 2 for a detailed description of measures). These values are only meaningful at frequencies where periodic changes occur. To identify these frequencies, peaks in spectral density are identified (see Figure 4); the peaks correspond to periodic patterns observed in the LV velocity at the peaks frequency (Janacek, 2008). The area under a peak’s curve is the amount of variability the LV velocity accounted for in the corresponding periodic pattern. The larger the spectral density at a peak, the greater the frequency accompanying that peak accounts for the variability in the LV velocity. Given that the LV velocity was generated by summing three sinusoids, the spectral density resulted in three peaks (see Figure 4)

Table 3.

Example of output from spectral analysis from data of one subject taken over the frequency of 0 to pi. Each row represents data for a particular frequency. Because of the large output not all data is shown. The dots represent data excluded. The bold text corresponds to the peak spectral densities seen in Figure 4. The values for coherence, gain (calculated from ratio of the spectral densities), and delay (calculated from phase) for only the shaded row were used in our analysis. For example, this subject had a coherence of 0.782245, a gain of 2.1457 (gain=325.5543 / 151.7221), and a delay of 2.79 seconds (delay = 0.610183 / 0.003641*60 = 2.79)

| Frequency from 0 to pi |

PERIOD | Spectral Density of LV Velocity |

Spectral Density of Subject Velocity |

Coherence of LV Velocity and Subject Velocity |

Phase of LV Velocity and Subject Velocity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ∙ | 9.153427 | 28.39758 | 0.848598 | −6.83E-21 |

| ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ |

| ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ |

| 0.003641 | 1725.571 | 151.7221 | 325.5543 | 0.782245 | 0.610183 |

| ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ |

| ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ |

| 0.008843 | 710.5294 | 24.54625 | 21.71756 | 0.861926 | 1.721934 |

| ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ |

| ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ |

| 0.012484 | 503.2917 | 10.28302 | 10.17416 | 0.235767 | 2.236869 |

| ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ |

| ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ | ∙ |

| 3.141333 | 2.000166 | 1.73E-08 | 4.35E-07 | 0.353135 | −0.8161 |

Figure 4.

Illustration of the periodogram for the LV velocity. Three peaks in the spectral density exist, representing the main periodicities of the LV velocity.

This study used a coherence threshold of 0.3 to determine which subjects should be included in the analysis. Values below this threshold indicate that the participant is not engaged in the car following task. Based on this cutoff value seven participants were excluded from the analyses for gain, delay and coherence (see Table 4). The percentage of participants excluded from the analysis did not differ significantly between groups (p=0.6276).

Table 4.

Number of Participants Deleted Due To Low Coherence

| MDMA | THC | ALCOHOL | NO DRUG | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coherence<0.3 (Not included in analysis) | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Coherence>0.3 (Included in analysis) | 16 | 35 | 23 | 38 | 112 |

| Total number of participants | 16 | 39 | 24 | 40 | 119 |

Gain, coherence, and delay were calculated for only the largest spectral peak because not enough data was available for the two smaller sine waves. Specifically, 39 of 119 participants had coherence < 0.3 for at least one of the smaller sine waves. In contrast, only seven participants were excluded for the Fourier analysis on the large sine wave (See Table 4). The analysis technique used in this study is similar to the methods of Brookhuis et al. (1994) who used measures of coherence, gain, and delay obtained from the single most appropriate frequency and differs from the methods of Andersen and Ni (2005) who used the averages of those measures at the three peaks for their analysis.

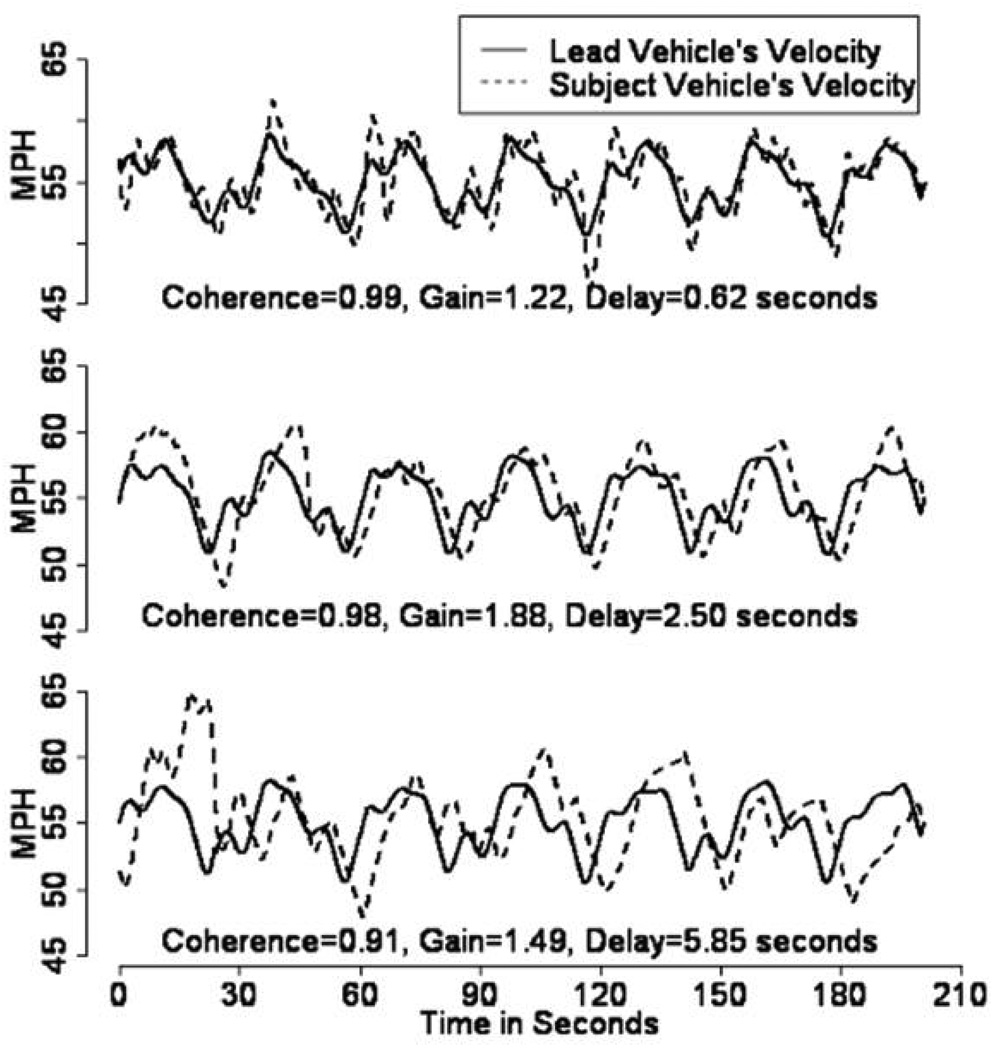

Figure 3 (embedded within Table 2) depicts the relationship between coherence, delay and gain in three different drivers. All participants have a high coherence indicating that during the car following task they modulated their velocity according to the behavior of the LV. However, delay differs between the three participants. The first participant’s delay is 0.62 s, the second participant’s delay is 2.50 s, and the third participant’s delay is 5.85 s. Larger delays, as demonstrated by greater shifts to the right, are less safe because they indicate slowed responses to changes in the LV velocity. Consequently, of these three measures delay may be considered the most relevant to driving safety (de Waard and Brookhuis, 2000).

Figure 3.

Demonstration of delay in subjects with a high coherence.

Additional measures of car following included mean and standard deviation of following distance. These measures were calculated for all participants, even those excluded from the Fourier analysis.

3.2 Statistical Analysis

We used non-parametric techniques to analyze the data in order to minimize the effect of outliers. We used Kruskal - Wallis tests to compare the four groups with respect to car following and coherence measures, as well as age. Gender distributions between the groups were compared using Fisher’s exact test. We converted our response variables to ranks before using an analysis of covariance regression model to adjust for age and gender when testing for group effects.

4. Results

Table 5 summarizes the group means and the Kruskal-Wallis test results between the different driver groups for the different car following measures. Average coherence for the groups ranged from 0.80 to 0.87 and did not differ between the four groups (p=0.3756). This indicates that abstinent MDMA users, abstinent THC users, abstinent alcohol users and no drug controls all matched the velocity changes of the LV well, and to similar extent. The gain was similar among the four groups indicating similar overshoot/undershoot levels for these groups. However, delay differed between the groups even after adjusting for age and gender (p=0.0048). Specifically, the abstinent MDMA users and abstinent THC drug users had shorter delays than the abstinent alcohol users and non-drug users (p= 0.0018). Delay did not differ between abstinent MDMA and abstinent THC users (p=0.4434) or between alcohol users and controls (p=0.6359). This suggests that abstinent drug users reacted faster to the LV velocity changes.

Table 5.

Car following and coherence measures

| MDMA mean (sd.), median |

THC mean (sd.), median |

ALC mean (sd.), median |

NO DRUG mean (sd.), median |

Kruskal- Wallis p-value |

Age and Gender Adjusted p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coherence | 0.87 (0.09), 0.89 | 0.84 (0.13), 0.89 | 0.80 (0.16), 0.86 | 0.82 (0.15), 0.87 | 0.3756 | 0.2198 |

| Gain | 1.75 (0.34), 1.86 | 2.09 (0.85), 1.84 | 2.07 (1.09), 1.61 | 1.71 (0.57), 1.62 | 0.2623 | 0.6657 |

| Delay(s) | 2.36 (0.72), 2.41 | 2.20 (1.08), 2.10 | 3.10 (1.39), 3.00 | 3.40 (1.63), 2.95 | 0.0036 | 0.0048 |

| Average Following Distance (ft) | 90.58 (29.27), 88.04 | 139.78 (169.20), 104.64 | 120.83 (38.61), 116.22 | 155.27 (181.72), 109.48 | 0.0075 | 0.0170 |

| Standard Deviation of Following Distance (ft) | 20.27 (10.08), 17.97 | 71.98 (237.66), 25.30 | 37.39 (27.23), 24.60 | 43.22 (81.62), 23.15 | 0.0572 | 0.0762 |

Mean and SD following distance were calculated for all participants, including the seven excluded from calculations of gain and delay measures due to low coherence (<0.3). SD following distance differed between groups, with abstinent MDMA users having a lower value than the other groups. The average following distance for the MDMA group was smaller than the other groups even after adjusting for age and gender (p=0.0170; all pairwise p-values<0.01). Average following distance was highly correlated with coherence, delay, and SD of following distance (see Table 6). This suggests that although MDMA users were less variable in their following distance and had shorter delays than drivers who had not used MDMA they did so at the risk of driving closer to the LV.

Table 6.

Correlation between average following distance and other car following measures

| Correlation | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Deviation of Following Distance (ft) | 0.8065 | <.0001 |

| Coherence | −0.5635 | <.0001 |

| Gain | −0.0731 | 0.4437 |

| Delay | 0.5150 | <.0001 |

5. Discussion and Limitations

Car following is a ubiquitous driving task and a key factor in collision avoidance and crashes. Safe drivers monitor, anticipate, and adjust to changes in LV velocity and position. Safe drivers also adopt longer following distances, allowing sufficient time to react to changes in LV cadence. Failure to do so may result in rear-end collisions, which are among the most common crash types accounting for 29.6 percent of police reported crashes in the United States in 2005 (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2007). Impaired car following may be due to cognitive slowing, distraction, decreased vigilance, failure to recognize perceptual cues (such as a LV slowing), aggression, and high levels of risk acceptance (e.g. short following distances) or risk taking behavior.

Owing to the vicissitudes of the roadway, including changing road terrain, speed limits and traffic patterns, and driver goals and behaviors, LV velocities often vary. Two vehicles may be traveling the same velocity with constant distance, but if the LV brakes and the driver does not the vehicles may collide (time headway and time to contact converge to zero). If the following vehicle brakes in response to the LV, then both accelerate, they may return to the equilibrium with safe time headway. However, if the driver adopts a short headway distance to other vehicles even short delays in response to LV slowing by a vigilant driver may not be fast enough to avoid a collision.

Abstinent MDMA users were vigilant to changes in LV velocity based on coherence values for car following that resembled those on all other groups. All members of the MDMA group met coherence criteria consistent with cooperation the car following task. Also, the MDMA group matched amplitudes of velocity changes by the LV as well as all the other driver groups (as demonstrated by gain). This finding differs from that Raemakers et al. (2006) and Kuypers et al. (2006) who found that drivers who ingested MDMA before driving overreacted to LV velocity changes. The differences with this study may reflect effects of acute ingestion in that study versus abstinence in the current study, as well as methodological differences in how the car following task was implemented. In the current study, standard deviation of following distance in the MDMA group was smaller than in controls, indicating tighter vehicle control. These results militate against a deficit in vigilance or visuomotor control in the MDMA group compared to the control groups.

Car following measures tend to correlate with average following distance (Brookhuis et al., 1994; Weiler et al., 2000). Abstinent MDMA users and abstinent THC users had shorter delay times compared to drivers in the abstinent alcohol condition and the no drug condition. These quicker reactions are necessary to compensate for shorter following distances. Participants who follow closely must adjust more quickly to avoid a crash. Abstinent MDMA users accepted the risk of following more closely with the need to react more quickly to changes in LV velocity. The use of multiple control groups to control for other drug use helped demonstrate MDMA use to be an underlying factor in risky driving. THC users performed the car following task as well as the MDMA group, having similar delays, and all groups had similar coherence and phase values. However, none of the control groups, including the THC group, followed as closely as the MDMA group.

While all participants traveled approximately 55 mph (80 ft/s), the MDMA drivers showed a mean 1.04 second shorter delay than non-drug using comparison drivers (leaving 83 more feet to respond) but drove 64 feet closer to the LV. Although abstinent MDMA users drove closer to the LV, they compensated for the risk of driving close by reacting quickly to the LV velocity changes. Risk taking drivers performing within such a slim envelope of safety may decompensate under the additional load of secondary tasks (Weiler et al., 2000), such as tuning a radio, eating, conversing, or using an iPod or cell phone while driving in the car.

One outstanding issue remains as to whether these risky driving behaviors associated with MDMA are consequences of the pharmacological effects of MDMA itself on the brain (or the residual effects of these actions). Alternatively, these individuals could have had abnormal mechanisms of decision making and impulse control that predated MDMA use, and in fact, these abnormal mechanisms may have served as predisposing factors that facilitated both MDMA use as well as risky driving. Indeed it has been argued that predisposition to risky behaviors relates to abnormal functions in the prefrontal cortex, which is key to mechanisms of decision making and impulse control (Bechara, 2005). These abnormalities may be either genetically based (i.e. related to abnormal dopamine or serotonin systems that modulate prefrontal cortex functions) or environmentally induced. In the latter case prefrontal cortex matures much later in life, and thus during this period, its development is vulnerable to many epigenetic or environmental factors such as early stress (Bechara, 2005). These “nature-nurture” issues remain difficult to disentangle and provide a rich substrate for ongoing research.

6. Conclusions

In summary, a car following task implemented within the controlled environment of a driving simulator provided novel evidence on driver performance in abstinent drug users, which could not be safely or ethically collected in an on-the-road test. Although standard measures of car following such as average and SD following distance are useful, they may fail to capture aspects that explain key underlying mechanisms of driver performance and behavior. Measures derived from Fourier analysis appear to give more information about the nature and quality of car following behavior. In this study we examined the residual effects of drug use on car following and found that only SD of following distance and delay differentiated abstinent users of MDMA from the other control groups. The results show patterns of risk taking behavior in abstinent MDMA users differed from the behavior of controls, suggesting differences in neural mechanisms underlying judgment, decision-making, and other executive functions. The car following scenario used is capable of examining performance decrements brought about by changes in vigilance and risk taking. This scenario represents a useful tool to examine the effects of drugs, alcohol, fatigue, and stress on an everyday driving task. Using a standard format may be suitable for clinical trials in driving populations in driving simulators across different institutes and allow for direct comparison.

Figure 2.

LV’s velocity pattern

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dick de Waard, John Andersen, Ben Mulder, Rui Ni and Joseph Cavanaugh for correspondence on the analysis of car following performance data.

Supported by NIDA DA017341 and NIA AG17177

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andersen GJ, Ni R. The spatial extent of attention during driving. 3rd International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training and Vehicle Design; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Risky business: emotion, decision-making and addiction. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2003;19:23–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1021223113233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Decision-making, impulse control, and loss of willpower to resist drugs: A neurocognitive perspective. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(11):1458–1463. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolla K, et al. Memory impairment in abstinent MDMA ("ecstasy") users [see comments] Neurology. 1998;51:1532–1537. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookhuis K, et al. Measuring driving performance by car-following in traffic. Ergonomics. 1994;37(3):427–434. [Google Scholar]

- Brookhuis K, et al. Effects of MDMA (ecstasy), and multiple drugs use on (simulated) driving performance and traffic safety. Psychopharmocology. 2004;173:440–445. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1714-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Man R. Morbiditeit en sterfte als gevolg van ecstacygebruik. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1994;138:1850–1855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waard D, Brookhuis KA. Drug effects on driving performance. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;133:656. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzoulis Mayfrank E, et al. Impaired cognitive performance in drug free users of recreational ecstasy (MDMA) [see comments] Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2000;68:719–725. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.6.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J, Jeffreys K, Dawling S. Toxicity and deaths from 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine ("ecstasy") [see comments] Lancet. 1992;340:384–387. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91469-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janacek GJ. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. 2nd Edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2008. Spectral analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Krystal J, et al. Chronic 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) use: effects on mood and europsychological function? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1992;18:331–341. doi: 10.3109/00952999209026070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuypers KPC, et al. MDMA and alcohol effects, combined and alone, on objective and subjective measures of actual driving performance and psychomotor function. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187:467–475. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0434-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers CTJ, Rizzo M, Bechara A, Ramaekers J. Simulated driving and attention of repeat users of MDMA and THC compared with THC users and non-drug-using controls. Transportation Research Record. 2006a;1969:50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lamers CTJ, Bechara A, Rizzo M, Ramaekers J. Cognitive function and mood in MDMA/THC users, THC users and non-drug using controls. Journal of psychopharmacology. 2006b;20:302–311. doi: 10.1177/0269881106059495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan B, Couper F. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy) and driving impairment. Journal of Forensic Science. 2001;46:1426–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann U, et al. Cognitive performance in (+-) 3,4-methylenedioxymethampetamine (MDMA, 'ecstacy') users: a controlled study. Psychopharmacology. 1999;143:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s002130050967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DV, et al. Quantitative analysis of steering adaptation on a high performance fixed-base driving simulator. Transportation Research, Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behavior. 2004;7(3):181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M. Memory deficits associated with recreational use of "ecstasy" (MDMA) Psychopharmacology. 1999;141:30–36. doi: 10.1007/s002130050803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M. Ecstasy (MDMA): a review of its possible persistent psychological effects. Psychopharmacology. 2000;152:230–248. doi: 10.1007/s002130000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts 2005. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation; 2007. (Rep. DOT HS 810 631) [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC, Lasky J. Ecstasy (MDMA) effects upon mood and cognition: before, during and after a Saturday night dance. Psychopharmacology. 1998;139:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s002130050714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC, et al. Cognitive performance in recreational users of MDMA of 'ecstasy': evidence for memory deficits. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1998;12:79–83. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC. Human psychopharmacology of Ecstasy (MDMA): a review of 15 years of empirical research. Human Psychopharmacology-Clinical and Experimental. 2001;16:557–577. doi: 10.1002/hup.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaekers JG, et al. Stimulant effects of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) 75 mg and methylphenidate 20 mg on actual driving during intoxication and withdrawal. Addition. 2006;101:1614–1621. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo M, Lamers CTJ, Sauer CG, Ramaekers JG, Bechara A, Andersen GJ. Impaired perception of self-motion (heading) in abstinent ecstasy and marijuana users. Psychopharmacology. 2005;179:559–566. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano F. Dangerous driving and MDMA ('Ecstacy') abuse. Journal of Serotonin Research. 1995;1:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Simulator Users Group. [Accessed 7/27/2008]; http://www.engineering.uiowa.edu/simusers/Scenarios/scenarios.htm.

- Rizzo M, et al. Stops for cops: Impaired response implementation in older drivers with cognitive decline. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2005;1922:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Verkes R, et al. Cognitive performance and serotonergic function in users of ecstasy. Psychopharmacology. 2001;153:196–202. doi: 10.1007/s002130000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler JM, et al. Effects of fexofenadine, diphenhydramine, and alcohol on driving performance. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the Iowa Driving Simulator. Ann Intern Med. 132:354–363. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-5-200003070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]