Abstract

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a chronic, autoimmune condition involving the skin and mucous membranes. Symptomatic mucosal involvement is rare, but can impact on quality of life, due to esophageal strictures and dysphagia. We report a case involving a 60-year-old male presenting with bullous skin lesions on areas of friction on his hands, feet and mouth. Milia were visible on some healed areas. Biopsy showed a subepidermal vesicle. Direct immunofluorescence showed intense linear junctional IgG and C3 at the dermo-epidermal junction. Serological tests also supported the diagnosis of EBA. Screening tests for underlying malignancies were negative. Despite treatment with systemic steroids, the patient developed increasing dysphagia, requiring further investigation with esophagoscopy and a barium swallow. Confirmation of extensive esophageal stricturing prompted adjustment of medications including an increase in systemic steroids and addition of azathioprine. Currently, the patient's disease remains under control, with improvement in all his symptoms and return of anti-basement membrane antibody levels to normal, whilst he remains on azathioprine 150 mg daily and prednisolone 5 mg daily. This case highlights the fact that the treatment of a given patient with EBA depends on severity of disease and co-morbid symptoms. Newer immunoglobulin and biological therapies have shown promise in treatment resistant disease. Considering that long-term immunosuppressants or biologicals will be required, potential side effects of the drugs should be considered. If further deterioration occurs in this patient, cyclosporin A or intravenous immunoglobulin (IV Ig) will be considered. Vigilance for associated co-morbidities, especially malignancies, should always be maintained.

Keywords: Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, vesicles, bullae, dysphagia, esophageal strictures, scarring, milia

Introduction

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a chronic, autoimmune condition of the skin and mucous membranes, leading to recurrent vesicles and bullae.[1] Progressive complications can lead to significant morbidity and mortality, with scarring of affected areas interfering with normal physiological functions. In particular, the involvement of mucosal membranes can lead to troublesome esophageal strictures and dysphagia. We report a case of EBA with dysphagia, which developed months after the onset of localized inflammatory disease, a rare but important complication to recognize and promptly treat.

Case Report

A 60-year-old male was referred for further investigation of recurring bullous skin lesions of 3 months duration on his hands, feet and mouth. The first episode had been diagnosed as hand-foot and mouth disease by a general practitioner, and had subsided after treatment with a short course of prednisolone. However, increasing lethargy and ongoing blister formation, especially at sites of trauma, prompted referral for a dermatological opinion.

Routine hematological and biochemical investigations revealed the following: a raised white cell count (14.7 × 109/L: neutrophils 11.4 × 109/L), C-reactive protein (CRP) 24 mg/L, and liver enzymes including gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) (68 U/L) and alanine transaminase (ALT) (88 U/L) out of normal parameters. Further investigations to exclude infectious and immunological causes including hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, rheumatoid factor, extractable nuclear antigens, and anti nuclear factor were all negative. Results demonstrated past infection with cytomegalovirus. Other past medical conditions included gout, hypercholesterolemia and gastro-esophageal reflux disease. There was no previous history of pemphigus, pemphigoid, other autoimmune conditions or malignancies. No significant family history was reported.

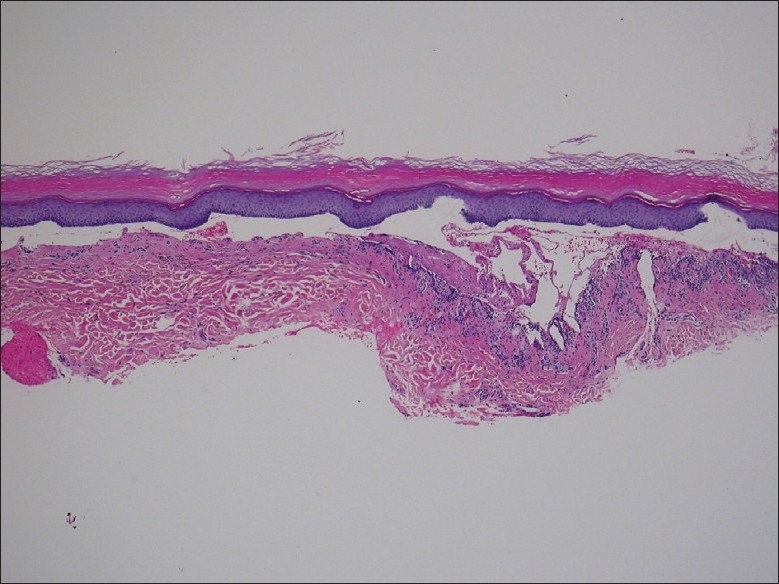

On examination, multiple vesicles and bullae were present over the hands, feet, upper and lower limbs and in the mouth. There was a predilection for sites with friction, including the sole of the foot, medial malleolus, elbows and finger tips [Figures 1 and 2]. A biopsy was taken of a new lesion on the patient's right wrist and sent for histopathology and immunofluorescence. Results demonstrated separation of the epidermis from the dermis, with formation of a subepidermal vesicle [Figure 3]. Fibrinous material and a mixed lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate were seen with no significant eosinophilia. Direct immunofluorescence showed intense linear junctional IgG and C3 at the dermo-epidermal junction, localized to the dermal aspect of the dermo-epidermal split. Serological tests for circulating anti-basement membrane (junctional) autoantibodies were significantly positive (2 in a scale of 0–3). Intercellular antibodies were negative. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of EBA.

Figure 1.

Bullous lesions on trauma prone areas of the hand. These lesions were approximately 4–5 days old

Figure 2.

Similar bullous lesions observed over the foot

Figure 3.

Subepidermal vesicle (H and E, ×40)

The patient was started on oral prednisolone 20 mg daily, omeprazole 20 mg daily, calcium and multivitamin supplements. Osteoporosis screening, a chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasound were all normal. Additional measures such as wearing gloves and larger sized shoes helped decrease the development of new lesions. Over the next few months, the patient's prednisolone dose was titrated according to his symptoms. Healing was seen with milia (0.5–1 mm in diameter) formation over scar sites. Three months later, the patient continued to develop new vesicles over the lumbar region and trunk. He experienced increasing irritation and teariness of his left eye and was referred for an ophthalmology opinion. Uveitis was ruled out. In the next month, azathioprine 50 mg daily was added, with regular monitoring of blood tests. The dose of azathioprine was then doubled to try and control symptoms.

Nine months after the initial presentation, the patient noted increasing dysphagia, especially for firm, solid foods such as meat. This gradually progressed, and a gastroscopy was performed, demonstrating desquamation, ulceration and scarring involving the first 4 cm of the esophagus. The gastroscope could not be passed further due to a stricture. Evaluation with a barium swallow showed a stricture of the proximal esophagus, measuring 6 mm proximally and extending about 10 cm. His medications were reviewed and prednisolone was increased to 50 mg daily and azathioprine was increased to 150 mg daily.

A follow-up gastroscopy 2 months later revealed an improved endoscopic appearance, with minor mucosal desquamation and reduction in stenosis of the proximal esophagus to 9 mm, with good distal views. Subjectively, the patient felt that his swallowing had improved. Since the diagnosis of disease, he has lost over 20 kg. Currently, the patient has regained his appetite and is experiencing increased levels of energy, with reduction in the number and severity of blisters. Recent blood tests demonstrate that his intercellular and junctional antibody levels have returned to normal levels and he remains on a maintenance dose of azathioprine 150 mg daily and prednisolone 5 mg daily.

Discussion

EBA is a rare, autoimmune subepidermal blistering skin condition characterized by abnormal immunoglobulins against a predominant component of the basement membrane, collagen VII.[1] The epidermal basement membrane zone consists of different proteins and collagenous structures that facilitate attachment of the epidermis to the dermis. Collagen VII has been identified as the major component of anchoring fibrils and is involved in a series of complex interactions.[2] Presence of abnormal autoantibodies leads to separation of the dermo-epidermal junction and formation of subepidermal blisters. There have been recent studies demonstrating pathogenic EBA autoantibodies to an additional domain – the cartilage matrix protein subdomain of noncollagenous 1.[3] Histopathological findings include subepidermal blistering, with a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate low in eosinophils and minimal blood vessel wall thickening. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 at the dermo-epidermal junction.[4,5] Bullous pemphigoid has a similar immunofluorescence appearance, but can be distinguished from EBA by salt skin splitting where the dermal-epidermal junction is fractured through the lamina lucida zone and the bullous pemphigoid antigen is placed on the epidermal side, whereas EBA antigens are found on the dermal side.[6]

Clinically, there are three main forms of disease presentation, with the non/mildly inflammatory form of EBA being the commonest. Clinically, the major differential diagnoses for EBA include bullous pemphigoid, cicatrical pemphigoid, bullous lupus erythematosus and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In some circumstances, the disease may extend to involve larger areas of the body and the mucous membranes. If this occurs, changes associated with healing and remodeling lead to complications such as esophageal strictures and dysphagia.[5,7] Mucosal involvement is often associated with increased morbidity due to development of life-threatening complications, which can be silent until the advanced stages of disease.[8]

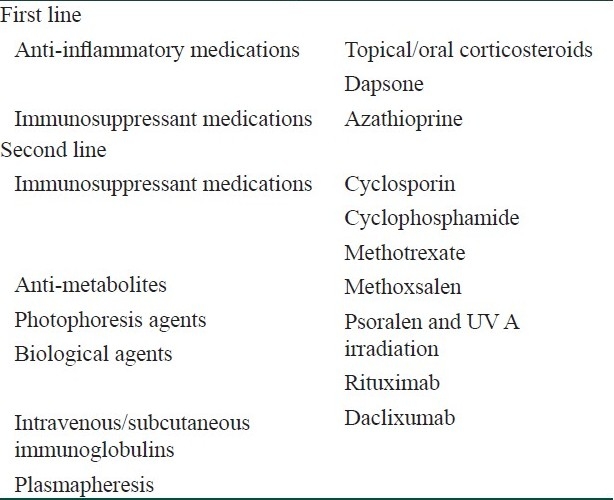

Optimal treatment of the disease remains controversial. The current mainstay of therapy consists of a combination of oral corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, guided by the severity and body areas affected by disease. A multidiscliplinary team approach is beneficial, with the development of symptoms such as gastrointestinal disturbances, oral and ocular involvement prompting referral to relevant clinical specialists.[8] In patients who have EBA resistant to conventional treatment, newer, novel therapies including intravenous immunoglobulin and biological agents provide additional treatment options [Table 1].

Table 1.

Treatments used in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

In patients with extensive mucosal involvement, local and systemic treatments have been trialled with varying success. In 1999, four patients diagnosed with EBA and mucosal membrane involvement were studied over 5 years. Comprehensive evaluation of the nasal cavity, pharynx and larynx by endoscopy, ophthalmological evaluation by slitlamp examination and non-invasive videofluoroscopy to assess oropharyngeal/esophageal regions were carried out.[8]

Treatment of affected patients is guided by the severity of mucosal disease. Local treatments including topical steroids, irrigation with saline solution and intranasal lubricant were employed with variable success. The importance of treating esophageal reflux symptoms was highlighted to prevent complications such as laryngeal injury and voice changes.[8]

EBA has been known to be associated with internal malignancies (e.g., lung, bowel, hematological). Fortunately, we did not detect any evidence of malignancy in this patient.

Progressive dysphagia and demonstration of esophageal narrowing on endoscopic examination may be alleviated by local procedures such as esophageal dilation.[9,10] In our patient, repeat endoscopy demonstrated improvement in endoscopic appearance and a reduction in esophageal stricturing. If esophageal narrowing further advances, dilation procedures would be considered.

Patients with EBA are known for being resistant to treatment and multiple therapies often have to be used to control symptoms and prevent complications. After corticosteroid therapy, use of immunosuppressants such as azathioprine and cyclosporin may provide additional benefits.[5] More recently, immunomodulators and biological agents including intravenous immunoglobulins (IV Igs), daclixumab and rituximab have been trialled.

Patients suffering from treatment resistant disease and severe complications have been trialled on IV Ig therapy with promising results. A young 16-year-old boy with resistant EBA was started on high dose IV Ig, which resulted in clinical control and remission of the disease.[11] In subsequent years, the benefit of IV Ig has been reported as monotherapy and in combination with other agents.[12–14] More recently, subcutaneous immunoglobulin therapy has shown promise as maintenance therapy, particularly benefiting patients with difficult venous access and providing the option of home therapy.[15]

Rituximab and daclixumab are two humanized monoclonal antibodies which have been employed in extensive, resistant disease.[16] A 58-year-old female was hospitalized with extensive skin ulceration and infection. Four rituximab infusions were given weekly for a month, combined with mycophenolate mofetil and prednisolone. Within a week of starting the infusions, clinical improvement was seen and complete disease regression was achieved in 5 months.[16] A middle-aged male with extensive EBA was trialled on four infusions of rituximab and demonstrated rapid clinical improvement.[17] In both the cases, a sustained clinical response has been observed.[16,17]

Three patients with elevated Tac levels were treated with intravenous daclixumab (humanized anti-tac monoclonal antibody), with decreased lymphocyte CD 25 expression noted. In one patient, a favorable clinical response was seen, providing the option of decreasing steroid treatment.[18]

EBA is a severe, autoimmune blistering skin condition associated with potentially significant complications, especially if mucous membranes are affected. The treatment in a given patient depends on disease severity, esophageal symptoms, co-morbidities, patient's age and expectations. Newer immunoglobulin and biological therapies have shown promise in treatment resistant disease. Considering that long-term immunosuppressants or biologicals will be required, potential side effects of the drugs should be considered. If further deterioration occurs in this patient, cyclosporin A or IV Ig will be considered. Vigilance for associated co-morbidities, especially malignancies, should always be maintained.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Donald Ormonde, Consultant Gastroenterologist, St John of God Hospital, Subiaco, and Dr. Lawrence Yu, Consultant Pathologist, Dermatopathology WA, for their contributions. We also thank the patient involved for providing photographs.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Woodley DT, Briggaman RA, O′Keefe EJ, Inman AO, Queen LL, Gammon WR. Identification of the skin basement membrane autoantigen in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1007–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404193101602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMillan J, Akiyama M, Shimizu H. Epidermal basement membrane zone components: Ultrastructural distribution and molecular interactions. J Dermatol Sci. 2003;31:169–77. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(03)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M, Doostan A, Bandyopadhyay P, Remington J, Wang X, Hou Y, et al. The Cartilage Matrix Protein Subdomain of Type VII Collagen is Pathogenic for Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:2009–18. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medenica-Mojsilovic L, Fenske N, Espinoza C. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Direct immunofluorescence and ultrastructural studies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1987;9:324–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallel-Halevy D, Nadelman C, Chen M, Woodley DT. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: Update and review. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:712–8. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remington J, Chen M, Burnett J. Autoimmunity to Type VII Collagen: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita. In: Nickoloff B, Nestle F, editors. Dermatologic Immunity. Bbasel: London: Karger; 2008. pp. 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodley D, Briggaman R, Gammon W. Review and update of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Semin Dermatol. 1988;7:111–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luke MC, Darling TN, Hsu R, Summers RM, Smith JA, Solomon BI, et al. Mucosal morbidity in patients with epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:954–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.8.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shipman AR, Agero AL, Cook I, Scolyer RA, Craig P, Pas HH, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita requiring multiple oesophageal dilations. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:787–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postma G, Belafsky P, Koufman J. Dilation of an esophageal stricture caused by epidermolysis bullosa. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002;81:86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier F, Sönnichsen K, Schaumburg-Lever G, Dopfer R, Rassner G. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: Efficacy of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:334–7. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70189-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harman KE, Whittam LR, Wakelin SH, Black MM. Severe, refractory epidermolysis bullosa acquisita complicated by an oesophageal stricture responding to intravenous immune globulin. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1126–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.2576m.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohr C, Sunderkötter C, Hildebrand A, Biel K, Rütter A, Rütter GH, et al. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita using intravenous immunoglobulins. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:824–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gourgiotou K, Exadaktylou D, Aroni K, Rallis E, Nicolaidou E, Paraskevakou H, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: Treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:77–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tayal U, Burton J, Dash C, Wojnarowska F, Chapel H. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin therapy for immunomodulation in a patient with severe epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Clin Immunol. 2008;12:518–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crichlow S, Mortimer N, Harman K. A successful therapeutic trial of rituximab in the treatment of a patient with recalcitrant, high titre epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:194–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt E, Benoit S, Bröcker EB, Zillikens D, Goebeler M. Successful adjuvant treatment of recalcitrant epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with anti-CD 20 antibody rituximab. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:147–50. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egan CA, Brown M, White JD, Yancey KB. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with the humanized anti-Tac mAb daclizumab. Clin Immunol. 2001;101:146–51. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]