Abstract

Background: Cytochrome P450s (CYPs) are mono-oxygenases that metabolize endogenous compounds, such as fatty acids and lipid signaling molecules, and furthermore have a role in metabolism of xenobiotics. In order to investigate the role of CYP genes in fat metabolism at the molecular level, four Caenorhabditis elegans mutants lacking functional CYP-35A1, CYP-35A2, CYP-35A4, and CYP-35A5 were characterized. Relative amounts of fatty acids, as well as endocannabinoids, which regulate weight gain and accumulation of fats in mammals, were measured while fat contents in worms were visualized using Oil-Red-O staining. Results: The cyp-35A1 and cyp-35A5 mutants had a significantly lower intestinal fat content than wild-type animals, whereas cyp-35A2 and cyp-35A4 mutants appeared normal. The overall fatty acid compositions of CYP mutants did not alter dramatically, although modest but significant changes were observed. cyp-35A1 and cyp-35A5 mutants had significantly higher levels of C18:1n7 and lower C18:2n6c. All four mutants had higher relative amounts of C18:1n7 than the wild-type. In the cyp-35A5 mutant, the levels of the endocannabinoid anandamide were found to be 4.6-fold higher than in wild-type. Several fatty acid synthesis genes were over-expressed in cyp-35A1 including fat-2. Feeding oleic or elaidic triglycerides to wild-type animals demonstrated that cyp-35A1 transcriptional levels are insensitive to environmental exposure of these fats, while cyp-35A2, cyp-35A4, and cyp-35A5 were significantly down regulated. Conclusion: These results demonstrate a dynamic role for CYP-35A subfamily members in maintaining the diversity of fatty acid profiles in C. elegans, and more generally highlight the importance of CYPs in generating both structural and signaling fatty acid functions in other organisms.

Keywords: cytochrome P450, fatty acids, metabolism, gene expression, model organism

Introduction

Cytochromes P450 (CYPs) are mono-oxygenase enzymes that are found in most animals and plants. CYPs are known to oxidize a wide variety of exogenous compounds and also metabolize endogenous compounds such as steroids and fatty acids. From a toxicological perspective, understanding the endogenous functions of CYPs is important as the induction of these enzymes with xenobiotics is likely to affect the physiological processes involving CYPs (Amacher, 2010). Several studies have shown that human, mouse, or rat CYPs hydroxylate or epoxidize metabolically important fatty acids such as linoleic acid (C18:2n6), alpha-linoleic acid (C18:3n3), arachidonic acid (C22:4n6), eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5n3), adrenic acid (C22:4n6), and docosahexaenoic (C22:6n3) acid into bioactive compounds (reviewed in Konkel and Schunck, 2010). The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has 77 CYPs that can be classified into 16 families plus five cyp pseudogenes. The physiological importance of C. elegans CYPs can be predicted in gene knockout or knockdown studies. Knockout or RNA interference of cyp-35A2, −3, −4, or −5 leaves nematodes unable to accumulate fat normally (Ashrafi et al., 2003; Menzel et al., 2007). The CYP-35A family proteins are expressed in the intestine, which is a major location of fat stores (Ashrafi et al., 2003). In addition, C. elegans CYP-29A3 and CYP-33E2 are known to metabolize eicosapentaenoic acid into epoxy and hydroxy derivatives that serve as important endogenous signaling compounds (Kulas et al., 2008). CYPs-31A2 and −31A3 are required for the synthesis of lipids that are essential for embryonic development in C. elegans (Benenati et al., 2009). Moreover, C. elegans CYP-22A1 (a.k.a. DAF-9) is known to make steroidal ligands that bind to the nuclear hormone receptor (NHR) DAF-12, and thereby regulate several developmental processes (Gerisch et al., 2001; Jia et al., 2002).

Several factors are involved in the regulation of C. elegans fat stores. Initially, fat is stored as triacylglycerols both in intestinal lysosome-related organelles and in lipid droplets found in intestinal and epidermal skin-like cells and mobilized by lipases (Schroeder et al., 2007; Mullaney and Ashrafi, 2008; Zhang et al., 2010). Fatty acids are used for energy in the process of beta-oxidation, which occurs in peroxisomes and mitochondria and whose end product is acetyl-CoA (Zhang et al., 2010). If beta-oxidation is impaired, the lipid droplets grow in size (Zhang et al., 2010). The nematode takes up fatty acids from the diet, primarily as triglycerides, and also synthesizes them de novo from acetyl-CoA (Watts and Browse, 2002; Rappeleye et al., 2003). C. elegans can make all its necessary unsaturated and long chain fatty acids from short chain fatty acids with desaturase and elongase enzymes, respectively, and does not need to obtain essential fatty acids from diet as humans do (Watts and Browse, 2002; Kniazeva et al., 2004). C. elegans fatty acid desaturase and elongase genes are sequentially named fat-1 to 7 and elo-1 to 8, respectively. Palmitic acid (C16:0) comes mainly from diet, whereas longer fatty acids are mostly synthesized from shorter ones (Watts, 2009). The enzymes responsible for fatty acid synthesis and degradation are expressed in the fat-storing cells and regulated by transcription factors such as NHR-49 (Van Gilst et al., 2005a,b; Mullaney and Ashrafi, 2008).

Fatty acids can be metabolized into various signaling molecules (Konkel and Schunck, 2010). The fatty acid arachidonic acid is the molecular starting point of the arachidonic acid cascade, which includes the production of endocannabinoids. The endocannabinoids anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) are derived from membrane phospholipids through several routes (Awumey et al., 2008; Snider et al., 2010). In mammals, endocannabinoids modulate neurotransmission, affect mood and behavior, and are involved in inflammation. Over activity of the endocannabinoid system has been also associated with obesity by acting through the cannabinoid receptor CB1 in several tissues such as brain, adipose tissue, liver, pancreas, and skeletal muscle (Matias and Di Marzo, 2007; Maccarrone et al., 2010). CB1 antagonists alleviate obesity and improve the plasma lipid profile and insulin sensitivity in obese mice and rats (Cota et al., 2009; Jourdan et al., 2010). Endocannabinoids are also found in C. elegans (Lehtonen et al., 2008) although this nematode lacks direct orthologs of CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors (Elphick and Egertová, 2001; McPartland et al., 2006). C. elegans do have vanilloid receptors which can act as a receptor for AEA (Zygmunt et al., 1999). CYPs can metabolize AEA or its hydrolysis product arachidonic acid (C20:4n6) into signaling molecules such as hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs), epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), and 2-epoxyeicosatrienoyl glycerols (2-EGs; Bornheim et al., 1995; Snider et al., 2007, 2008; Chen et al., 2008; Stark et al., 2008).

Among the most important challenges in toxicology as proposed by Pelkonen (2010) is to develop testing systems to predict the toxicity potential of chemicals in an adequately reliable manner before humans or other living mammalian organisms have been exposed to them. In the current study, we demonstrate the utility of a non-mammalian model to understand the role of a CYP subfamily 35A that metabolizes both endogenous and exogenous compounds. We aimed to identify the role of the CYP-35A subfamily in the regulation and maintenance of different fatty acids molecules. While previous studies have suggested a role for CYP-35A family in fat storage, our goal was to take advantage of the unique genetic resources available in C. elegans and investigate fatty acid regulation at multiple levels. Using four different C. elegans CYP-35A family mutants, we assayed their ability to store fat. Fatty acid compositions were then measured to understand how the knockout of individual family members influenced the fatty acid profiles in whole animals. Moreover, endocannabinoid levels were measured in these mutants. Finally, gene expression changes were measured in fatty acid pathway genes to see how possible transcription changes might coincide with fatty acid changes. Using these multiple approaches, we observed a significant regulation of fatty acid molecules and changes in the transcriptional levels of genes controlling these molecules in cyp-35A family mutants. These results ultimately predict the regulation of fatty acid metabolism by members of the CYP-35A family.

Materials and Methods

Phylogenetics

The CYP protein sequences from H. sapiens and C. elegans were downloaded from the BioMart tool of the Ensembl database, and subsequently aligned with ClustalW2 and visualized as dendrograms with HyperTree 1.0.0 (Sugen Inc.; Flicek et al., 2010). Labels were manually added. Sequence alignments (Figure S1 in Supplementary Material) were visualized using JalView.

Worm strains and their growth

The worm strains RB1788, cyp-35A1(ok2306; 1494 bp deletion including first four exons of the coding region; VC710, cyp-35A2(gk317; 1245 bp deletion including four to seven coding exons and 3′UTR); RB1294, cyp-35A4(ok1393; ∼600 bp deletion); RB1613, cyp-35A5(ok1985; 367 bp deletion in three to four coding exon); and CB1370, daf-2(e1370; missense 1462 P–S) were received from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (Twin Cities, MN, USA). The nematodes were grown in standard conditions (Brenner, 1974).

Fat staining

Oil-Red-O (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was used to stain whole animals. The fatty acid staining was performed as described by O'Rourke et al. (2009). Synchronized day-1 adults were collected from plates and washed three times with 1× PBS. The worms were allowed to settle by gravity. To permeabilize the cuticle, 120 μL of PBS and 120 μL of 2 × MRWB buffer (Modified Ruvkun's Witches Brew; 160 mM KCl, 40 mM NaCl, 20 mM Na2EGTA, 10 mM Spermidine HCl, 30 mM Na-PIPES pH 7.4, 50% methanol) containing 2% paraformaldehyde was added. The 2× MRWB buffer used in our experiments contained an equal concentration of EDTA in place of Na2EGTA, and an equal concentration of HEPES in place of Na-PIPES. The nematodes were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with gently shaking and then washed with 1× PBS. To dehydrate the worms, 300 μL of 60% isopropanol was added and the samples were incubated for 15 min. The isopropanol solution was removed and 1 mL of 60% Oil-Red-O was added, as prepared in O'Rourke et al. (2009). The samples were incubated overnight with gentle shaking. The dye was removed and the nematodes were washed twice with 1× PBS, containing 0.01% Tween. The worms were resuspended in 1× PBS with 0.01% Tween, pipetted onto agarose pads and imaged with an Olympus AX70 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a UPlan Apo 60X/0.90 objective.

Overall fatty acid composition

Fatty acid profiles were measured from CYP mutants and N2 strains that were synchronized to the L4 stage by bleaching. A method similar to Watts and Browse (2000, 2002) was used for sample analysis. Briefly, to a 10-μL sample of worm pellet collected by centrifugation (∼350 g), 0.5 mL of 2.5% H2SO4 in methanol was added and samples were heated at 60°C for 1 h. After cooling the samples to room temperature, 1 mL of hexane and 1.5 mL of H2O were added and the mixture was vortexed. The phases were separated and the organic phase was evaporated to dryness under nitrogen at room temperature. The residue was dissolved in 100 μL of hexane for analysis. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were analyzed by gas chromatography coupled to electron ionization mass spectrometry (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) using a bis-cyanopropyl capillary column (100 m × 0.25 mm i.d.) with 0.20 μm film thickness (SP-2560, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) for analysis with pulsed split injection (1 μL). The oven temperature was held at 180°C for 2 min, then increased to 240°C at 3°C/min rate and held at 240°C for 8 min. The carrier gas was helium with constant flow of 21 cm/s. The temperatures of the MS transfer line heater, ionization source, and quadrapole were maintained at 250, 230, and 150°C, respectively. In the GC/EI–MS full scan and the selected ion monitoring modes were used for qualitative and quantitative analysis of FAMEs, respectively.

Gene expression of fatty acid synthesis and beta-oxidation genes

Total RNA was extracted from four separate L4 larval stage C. elegans cultures with RiboPure™ Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). For each replicate, 0.5 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed in a volume of 19 μL using 2 μL dNTP Mix (10 mM each, Fermentas Life Sciences, Vilnius, Lithuania), 4 μL 5× Reaction Buffer, and 1 μL RevertAid Minus M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (200 u/μL; Fermentas Life Sciences). The RT reactions were diluted 1:6 with nuclease free H2O. Real-time PCR was performed in a volume of 25 μL consisting of 12.5 μL of Maxima™ SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas Life Sciences), 0.2 μM (final concentration) of forward and reverse primers each in nuclease free H2O and 2.5 μL of the diluted RT reaction. The PCR reactions were performed in a MyiQ Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Life Sciences, Hercules, CA, USA). The oligo primers were purchased from Oligomer (Helsinki, Finland) and sequences were: act-1 forward, 5′-TCG GTA TGG GAC AGA AGG AC-3′; act-1 reverse: 5′-CAT CCC AGT TGG TGA CGA TA-3′; fat-1 forward, 5′-CGC CTT CTC ACC ACT CTT CT-3′; fat-1 reverse, 5′-TCC ACA CGT GTC CAT GAT CT-3′; fat-2 forward, 5′-TCC CGG CTC TTC GAG ACT AC-3′; fat-2 reverse, 5′-GAA TAG TCG CAG AGG ACA AAG G-3′; fat-3 forward, 5′-GAG GAG GCC TTT TGA TTG CT-3′; fat-3 reverse, 5′-TTG AAG AGC GGC GAA GTT-3′; fat-4 forward, 5′-ACA TCC AGG TGG TAG TGC AA-3′; fat-4 reverse, 5′-CTG GGA TCT CTG GTT CTT GTG-3′; fat-5 forward, 5′-CGC TCA TAT GGG ATG GTT GT-3′; fat-5 reverse, 5′-CAG GGC GAA GCA GAA GAT T-3′; fat-6 forward, 5′-GCC CAG AGA CGC AAT ATC TC-3′; fat-6 reverse, 5′-CAG CAA AGA GAG CCA CGT TA-3′; fat-7 forward, 5′-GCA GCC ATT GGA CTT TAC GA-3′; fat-7 reverse, 5′-GAT GGG CTC CAG CTG TGA TA-3′; elo-1 forward, 5′-GAA TTT CCC TGA CGC AGA AG-3′; elo-1 reverse, 5′-GTT CCG AAC ACA ACG ACC AT-3′; elo-2 forward, 5′-CCA GTG GCA AAG TTC ATC AC-3′; elo-2 reverse, 5′-TCC TCC GAT CGA TAG CAC AT-3′; elo-5 forward, 5′-TTG GAT CTT CCT TTG GGT TAT CT-3′; elo-5 reverse, 5′-TCA TGG TAG CAG ACA AGA GCA TA-3′; elo-6 forward, 5′-CTC AAT GGC ATA TGT TGT CGT TA-3′; elo-6 reverse, 5′-TCC GAG AGT TGA GAA AAT AGC AA-3′; acs-2 forward, 5′-TTG GAC TAT GTC GCT GAT GC-3′; acs-2 reverse, 5′-GCG GTG ATC TTT CCT TCA TC-3′. The act-1 primer set was used as the internal control and fold changes were calculated using the 2−(ΔΔCt) method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001; Asikainen et al., 2010).

Expression of cyp-35A genes in response to feeding of fatty acids

The triolein- and trielaidin-glycerides were purchased from Nu-Chek Prep (Elysian, MN, USA). Triolein-glyceride contained the pure cis-18:1n9 fatty acid. Trielaidin contained the pure trans-18:1n9 fatty acid. After melting the triglyceride in a water bath (above 25°C for the cis-triolein, above 75°C for the trans-trielaidin), each oil was dispersed into hot agar by magnetic stirring drops of oil of a previously weighted volume, to achieve a final concentration of 25 μM in the agar. Plates were cooled quickly after pouring the agar, and then stored in a cool, dark place before use, in order to keep these triglycerides evenly distributed throughout the solidified agar. Higher concentrations of triglycerides eventually resulted in the appearance of oil droplets on the agar surface. Gravid worms grown on NGM agar were collected and embryos obtained by bleaching. Embryos were then grown on triglyceride plates and collected for analyses at the L4 stage (∼48–56 h later).

Gene expressions of the cyp-35A1, cyp-35A2, cyp-35A4, and cyp-35A5 genes in wild-type nematodes with and without feeding of fatty acids were measured as described in Section “Gene Expression of Fatty Acid Synthesis and Beta-Oxidation Genes.” The oligo primers were purchased from Oligomer (Helsinki, Finland). Their sequences were: cyp-35A1 forward, 5′-CGG CAG AAG CCG TTA AAA G-3′; cyp-35A1 reverse, 5′-TGA CCA GTC ATC CAC AAA TCG-3′; cyp-35A2 forward, 5′-TTC TCC CTT CAA GCA TTT AGG A-3′; cyp-35A2 reverse, 5′-ATC GAA AAA TTC AGA GGC ATG T-3′; cyp-35A4 forward, 5′-ACC AAA TCA AGT CTG GGA GGT A-3′; cyp-35A4 reverse, 5′-GCC TGT TAT CCA TAA ATC ACC AA-3′; cyp-35A5 forward, 5′-TAC CTT TGG ACA ACT GGT GGT A-3′; cyp-35A5 reverse, 5′-AAG TCT CAT AAT CGG CAA TGC T-3′.

Endocannabinoids

The endocannabinoids were measured with liquid chromatography coupled to an electrospray-ionization triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (ESI–LC/MS/MS; Lehtonen et al., 2008). Briefly, synchronized fourth larval stage (L4) nematodes were collected from plates with M9 buffer. Twenty microliters of vortexed sample was transferred to an Eppendorf tube. One milliliter of MeOH was added and the samples were homogenized with a Soniprep 150 homogenizer (MSE Ultrasonic Disintegrator, MSE Scientific Instruments, Manor Royal, Crawley, Sussex, England). Lipids were extracted by adding 2 mL of CHCl3 and 1 mL of H2O, followed by centrifugation at 1500 × g and incubation at 10°C for 10 min to separate the phases. The aqueous upper layer was removed and the organic layer transferred to a screw-capped test tube. The lipid extraction was repeated on the obtained sample. The sample was evaporated to dryness under N2 and the residue was reconstituted in 50 μL of ice-cold ACN. The residue was allowed to dissolve for 5 min, after which 20 μL of H2O was added. The sample was centrifuged at 12000 × g and 10°C for 10 min and transferred to an HPLC sample vial.

Anandamide and 2-AG were quantified by liquid chromatography (Agilent 1200 series rapid resolution LC system, Agilent Technologies, D-Waldbronn) coupled with an ESI triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent 6410 triple quadrupole LC/MS, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Ten microliters of sample solution was injected onto a reversed phase HPLC column (Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 rapid resolution HT 2.1 mm × 50 mm, 1.8 mm, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) using an isocratic mobile phase consisting of 55% of 0.1% HCOOH in ACN and 45% of 0.1% HCOOH in H2O, delivered at 200 μL/min. Column temperature was maintained at 40°C and the autosampler tray temperature was set at 10°C. The following ionization conditions were used: ESI, positive-ion mode; drying gas (N2) temperature, 300°C; drying gas flow, 10 L/min; nebulizer pressure, 50 psi, and cap. voltage, 4000 V. Detection was performed using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) with the following transitions: m/z 348 → 62 for AEA, m/z 356 → 63 for AEA-d8, m/z 379 → 287 for 2-AG, and 387 → 294 for 2-AG-d8. Fragmentor voltage and collision energy for AEA, AEA-d8, 2-AG, and 2-AG-d8 were 120 and 10 V, 120 and 12 V, 130 and 8 V, and 125 and 10 V, respectively. Dwell time was 100 ms for each transition, and mass resolution for MS1 and MS2 quadrupoles were 2.4 and 1.2 FWHM, respectively, for AEA, and 0.7 and 0.7 FWHM, respectively, for AEA-d8, 2-AG, and 2-AG-d8. Deuterated internal standards, AEA-d8 and 2-AG-d8, were used for quantification.

Results

Phylogenetics

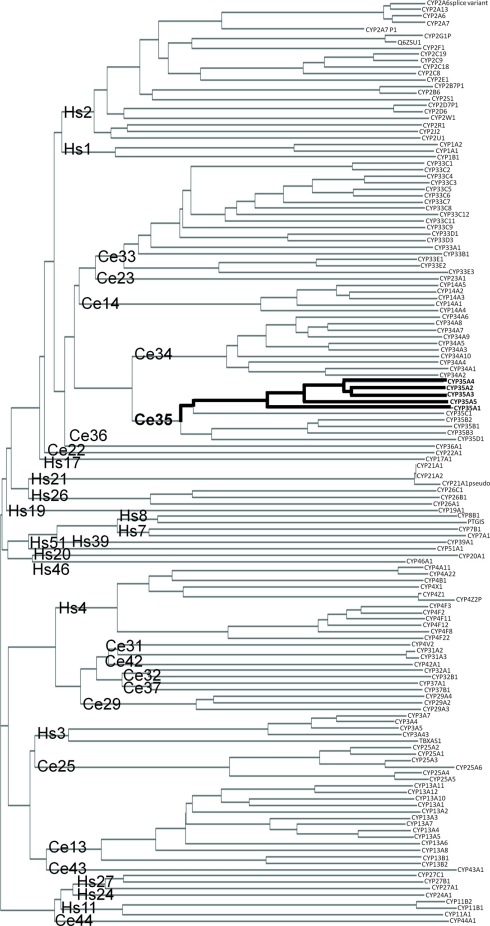

The C. elegans CYP-35 family is most closely related to C. elegans CYP-34 family. The closest human CYP families to C. elegans CYP-35 are CYP-1 (Hs1) and CYP-2 (Hs2). However, members of the major human families CYP-1 and CYP-2 clearly share more similarities with each other than with C. elegans families. Human CYP-3 (Hs3) and CYP-4 (Hs4) families are more closely related to C. elegans families other than CYP-35 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenic clustering diagram of Human (Hs) and C. elegans (Ce) cytochrome P450 genes. CYP protein sequences were downloaded from public databases and aligned as described in Section “Materials and Methods.” CYP family names are shown at the base of the tree and individual proteins are shown at the end of the branches. Location of the C. elegans CYP-35A family is indicated by the bolded line.

Within the C. elegans CYP-35A subfamily the peptides CYP-35A2 and −3 are the most similar (Figure 1). CYP-35A1 is the most different. Subfamilies B, C, and D are not as expanded as subfamily A. The amino acid sequences of the CYP-35A proteins are very similar at the N terminus from amino acid 0 to 100, and also from amino acid 300 to 400 with minor amino acid differences. CYP-35A1 is missing a 38 amino acid sequence that the other CYP-35A proteins have in the middle of the peptide chain (amino acids 254–291), and it has additional amino acids closer to the C terminus (Figure S1 in Supplementary material).

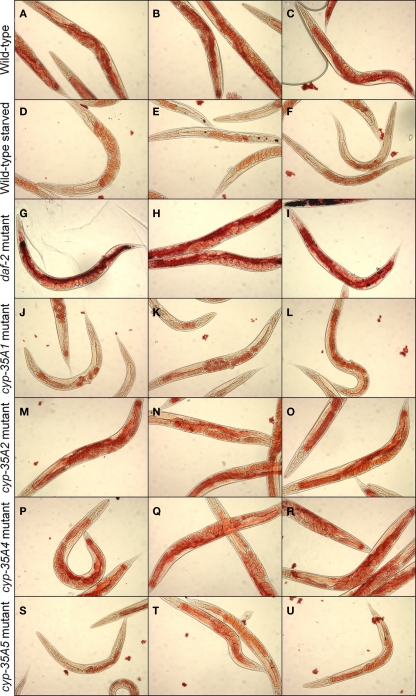

Fat staining in cyp-35A mutants

Wild-type N2 strain animals feeding on bacteria show abundant Oil-Red-O staining, particularly in the intestine and mature oocytes (Figures 2A–C). Animals starved for a day show loss of staining, in the intestine and less in oocytes (Figures 2D–F). The daf-2 mutant, as a positive control, showed heavy fat staining in the intestine (Figures 2G–I). In contrast, the cyp-35A1 mutant showed light Oil-Red-O staining in the intestine, mainly in the anterior part, and oocytes (Figures 2J–L), resembling the starved wild-type that also had staining in the eggs but not visible amounts in the intestine. The cyp-35A2 and cyp-35A4 mutants had about the same level of Oil-Red-O staining as the wild-type (Figures 2M–R). The cyp-35A5 had some Oil-Red-O staining in the intestine but visibly less than wild-type (Figures 2S–U).

Figure 2.

Fat content visualized by Oil-Red-O staining. N2, starved N2, daf-2, cyp-35A1, cyp-35A2, cyp-35A4, cyp-35A5. Animals were grown and treated as described in Materials and Methods. Staining was performed on populations of day-1 adult animals and photographed using transmitted light microscopy at 200 magnification. Panels shown are three typical fields per mutant or treatment. (A-C), wild-type; (D-F), wild-type starved; (G-I), daf-2 mutant; (J-L), cyp-35A1 mutant; (M-O), cyp-35A2 mutant; (P-R), cyp-35A4 mutant; (S-U), cyp-35A5 mutant.

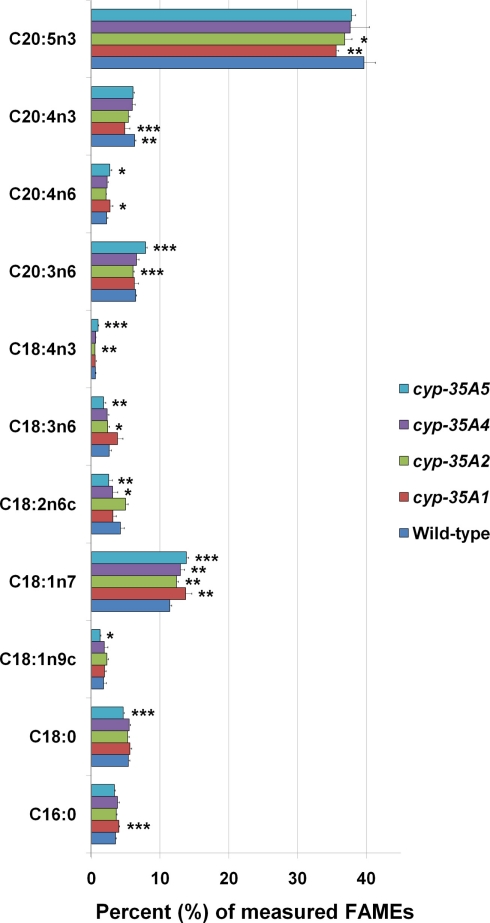

Fatty acid composition and endocannabinoid changes in cyp-35A mutants

The overall fatty acid compositions of CYP mutants did not alter dramatically, although modest but significant changes were observed (Figure 3). Compared to wild-type animals, cyp-35A1 mutants had significantly higher C16:0, C18:1n7, C18:3n6, and C20:4n6, while having significantly lower levels of C18:2n6c, C20:4n3, and C20:5n3 fatty acids. In concordance, cyp-35A5 mutants had significantly higher levels of C18:1n7 and lower C18:2n6c. All four mutants had higher relative amounts of C18:1n7 than the wild-type (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Fatty acid composition of cyp-35A1, −2, −4, and −5 mutants. Animals were synchronized to the L4 larval stage and assayed for fatty acids as described in Materials and Methods. Histograms represent percentages of the total amount of the fatty acids measured. Error bars represent SD. *t-test p-value < 0.05, **t-test p-value < 0.01, ***t-test p-value < 0.001, compared to wild-type N2. Some additional fatty acids were included in the assay but not included in the figure due to low concentrations (<1 nmol %) or lack of change.

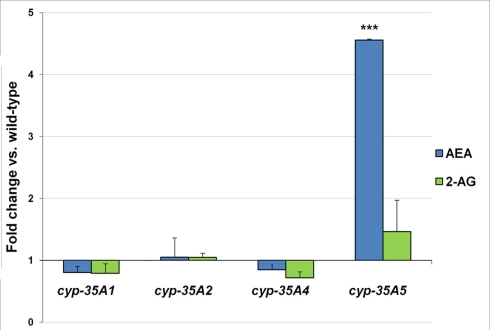

The endocannabinoid AEA was found to be 4.6-fold higher in the cyp-35A5 mutant than in the wild-type (Figure 4). 2-AG levels were not significantly altered in any of the mutants.

Figure 4.

L4 stage wild-type and mutant animals were collected and assayed for the endogenous cannabinoids. Fold changes of anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) amounts ± SEM in cyp-35A mutants are shown. ***t-test p-value < 0.001.

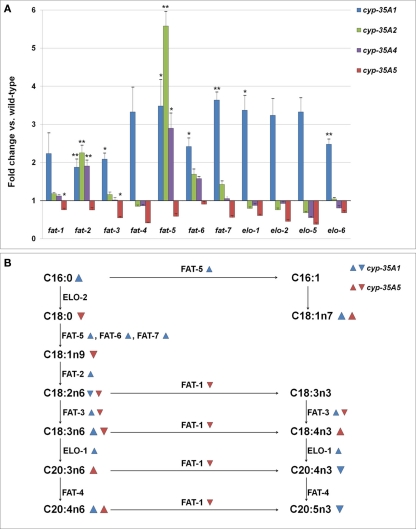

Gene expression changes of fatty acid synthesis genes and acs-2

In the cyp-35A1(ok2306) mutant many genes required in the synthesis of long chain fatty acids appeared to be expressed in 2–3.5 times higher amounts than in wild-type (Figure 5A). The increases in fat-2, fat-3, fat-5, fat-6, fat-7, elo-1, and elo-6 were significant (p < 0.05). In a different cyp-35A1(ok1414) mutant allele strain, only fat-2 was significantly over-expressed, but all the measured genes were found in somewhat higher amounts than in the wild-type (data not shown). In the cyp-35A5 mutant many fatty acid synthesis genes seemed to be under-expressed, although only the changes in fat-1 and fat-3 were significant. The fatty acid beta-oxidation gene acs-2 was slightly (1.7-fold) over-expressed in the cyp-35A2 mutant and under-expressed (fold change 0.8) in the cyp-35A5 mutant (data not shown).

Figure 5.

(A) Changes in the expression levels of fatty acid synthesis genes (fold change compared to wild-type ± SEM). *t-test p-value < 0.05, **t-test p-value < 0.01, ***t-test p-value < 0.001. (B) Schema of the synthesis of fatty acids and the enzymes involved.  = fatty acid percentage or gene expression increased in cyp-35A1 mutant,

= fatty acid percentage or gene expression increased in cyp-35A1 mutant,  = fatty acid percentage or gene expression decreased in cyp-35A1 mutant,

= fatty acid percentage or gene expression decreased in cyp-35A1 mutant,  = fatty acid percentage or gene expression increased in cyp-35A5 mutant,

= fatty acid percentage or gene expression increased in cyp-35A5 mutant,  = fatty acid percentage or gene expression decreased in cyp-35A5 mutant.

= fatty acid percentage or gene expression decreased in cyp-35A5 mutant.

A map of the fatty acid metabolism pathway was then drawn and significant changes in gene expression and fatty acids were placed onto the map. The top part of the map involving C16:0, C16:1, C18:0, C18:1n7 appears to be concordant: gene expression increases in fat-5 for the cyp-35A1 mutant are in agreeement with increases in C18:1n7. The middle portion of the map including C18:1n9, C18:2n6, C18:3n3,C18:3n6, C18:4n3 does not appear to be concordant. The bottom part of the map including C20:3n6, C20:4n3, C20:4n6, and C20:5n3 appears concordant, particularly the increases in C20:4n6 due to increases in elo-1 expression in cyp-35A1 animals (Figure 5B).

Expression of cyp-35A subfamily genes in response to feeding of cis- and trans-C18:1N9

In order to determine whether or not cyp-35A family genes respond to fat feeding, we fed wild-type animals oleic or elaidic triglycerides, which are the cis- and trans-triglycerides of C18:1n9, respectively. In wild-type C. elegans, the cyp-35A1 gene was not responsive to fat feeding, while cyp-35A2, cyp-35A4, and cyp-35A5 significantly decreased expression (Table 1). There was no differentiation when animals were fed cis- or trans-isomers of these triglycerides (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fold change ± SEM of the expression of cyp-35A family genes.

| cyp-35A1 | cyp-35A2 | cyp-35A4 | cyp-35A5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 cis/no feeding | 0.93 ± 0.19 | 0.66 ± 0.05* | 0.53 ± 0.05*** | 0.63 ± 0.05* |

| N2 trans/no feeding | 1.12 ± 0.61 | 0.38 ± 0.05** | 0.56 ± 0.10* | 0.50 ± 0.09* |

Significances of the alterations were determined with Student's t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

Phylogenetics

Caenorhabditis elegans CYP peptide sequences clustered similarly as in an early phylogenetic study by Gotoh (1998). The relatively large number of paralogs in the cyp-35 family indicates that these enzymes may function at least partly in xenobiotic metabolism (Thomas, 2007). This is also supported by studies showing that the cyp-35A family genes are induced by a number of xenobiotics (Menzel et al., 2001, 2005; Reichert and Menzel, 2005; Roh et al., 2007; Chakrapani et al., 2008). Further, as shown in phylogenetic comparisons between fish, insect, and human CYPs (Nelson, 2003; Feyereisen, 2006), we observed high similarities with human families CYP-1 and CYP-2, suggesting their relatively recent evolution probably in response to xenobiotic challenges. Those families were clustered together with several C. elegans CYP families (such as cyp-35 family), similarly as in fish and insects (Nelson, 2003; Feyereisen, 2006), indicating an evolutionally old distinction between the major CYP clades, probably due to their early separated endogenous functions, which in human include metabolism of fatty acid derivatives (Arnold et al., 2010). In the genome, the cyp-35 genes are located in a cluster on chromosome V, adjacent to each other and cyp-34 family genes. CYPs whose genes appear in clusters are more likely to be involved in xenobiotic metabolism than CYPs whose genes reside isolated from other cyp genes in the genome (Thomas, 2007). The closest human counterparts of the CYP-35A family, the highly diverse families CYP-1 and CYP-2, metabolize both exogenous and endogenous compounds, the latter including omega-3 and −6 fatty acids and their derivatives (Schwarz et al., 2004; Fer et al., 2008; Arnold et al., 2010). Nematodes C. briggsae and C. remanei have CYP-35A subfamilies but they are not as expanded as the C. elegans CYP-35A subfamily (data not shown). Vertebrates or insects do not have a CYP-35 family suggesting that CYP-35 enzymes may have a nematode-specific endogenous function.

Cyp-35A1 and cyp-35A5 mutants have a depleted fat content as visualized by Oil-Red-O staining

The lack of functional CYP-35A1 and CYP-35A5 leads to decreases in intestinal fat (Figure 2). This suggests that these CYPs are necessary, but not sufficient to maintain fat storage. The molecular mechanism by which these CYPs act may be complex. Genome-wide RNAi studies in C. elegans have revealed 305 gene inactivations that reduce body fat (Ashrafi et al., 2003). In addition to CYPs, signal transduction enzymes, receptors, transporters, and energy metabolism enzymes were found. Among the best studied fat storage regulators in C. elegans is NHR-49, a NHR, which has been shown to influence the regulation of 13 genes involved in energy metabolism (Van Gilst et al., 2005a,b). Several of these (fat-5, fat-6, and fat-7) overlap with those found to be regulated in this study, which suggests that CYPs and NHRs may share common pathways in the regulation of fat storage.

In earlier fat staining experiments with Nile Red, the cyp-35A2(gk317), cyp-35A3, cyp-35A4(ok1393), and cyp-35A5(ok1985) mutants were deficient in fat accumulation, but the cyp-35A1(ok1414) mutant was normal (Menzel et al., 2007). The study of Menzel et al. (2007) used a different allele of cyp-35A1 compared to our study, but the other strains used were the same. The reason for the different results could be the stains used. The Nile Red dye stains the lysosome-related organelles but not the lipid droplets (O'Rourke et al., 2009), and these differences could explain our results, as we used Oil-Red-O. Recently, other laboratories have used Oil-Red-O in place of Nile Red (Soukas et al., 2009; Horikawa and Sakamoto, 2010).

We investigated CYP-35A subfamily members −1, −2, −4, −5, as these mutants were readily available. A previous RNAi study showed that knockdown of cyp-35A3 and A5 reduced the fat content of wild-type animals (Ashrafi et al., 2003), possibly via cyp-35A2 and cyp-35A4 as secondary targets of the cyp-35A3 RNAi construct. The knockdown of the entire cyp-35A subfamily has an interesting phenotype: when cyp-35A1, cyp-35A3, cyp-35A5, and cyp-35C1 are silenced with RNAi in a cyp-35A2, cyp-35A4 double mutant background, the nematodes are more resistant to the reproductive toxicity of PCB52 than wild-type (Menzel et al., 2005). PCB52 is known to induce these genes (Menzel et al., 2001) and also increase the storage of fat, which may at least partially be the mechanism of its toxicity (Menzel et al., 2007). The silencing of cyp-35A genes with RNAi does not cause abnormalities in fertility, morphology, embryonic lethality, maternal sterility, larval lethality, growth, sterility of progeny, larval arrest, postembryonic development, or lethality (Kamath et al., 2003; Rual et al., 2004; Menzel et al., 2005; Sonnichsen et al., 2005).

Overall fatty acid compositions and anandamide are altered in cyp-35A mutants

The relative amounts of different fatty acids are affected in the cyp-35A subfamily mutants, although modestly. Indeed, most changes in fatty acid composition were only on the order of a few percent. The lack of large changes could be due to factors such as sampling, as whole animals were used for analysis and large local changes in composition could be diluted. Alternatively, we were not able to analyze the distribution of fatty acids in different subcellular fractions. Indeed, major changes in fatty acid composition profiles are typically only seen in C. elegans mutants lacking fatty acid desaturation and elongation enzymes (Watts and Browse, 2002; Kniazeva et al., 2004). Studies detailing the role of transcription factors regulating the fatty acid synthesis and metabolism pathway genes see more modest changes, in agreement with the present study (Van Gilst et al., 2005a,b; Taubert et al., 2006; Aarnio et al., 2010). Alternatively, these small changes might reflect the strong metabolic drive to maintain fat homeostasis.

In contrast, sharply elevated levels of the endocannabinoid AEA were found in the cyp-35A5 mutant. AEA increases weight gain and fat content in mammals (Matias and Di Marzo, 2007; Maccarrone et al., 2010). Thus, the elevation of AEA may be a homeostatic response to decreased fat content in cyp-35A5 mutant animals. AEA can be made of phospholipids containing arachidonic acid (C20:4n6; Snider et al., 2010). Consistent with this, we observed significant increases in C20:4n6 for cyp-35A1 and A5 mutants. In support of a prominent role of CYPs in controlling signaling lipid synthesis, pioneering work by Menzel and colleagues demonstrate the role of C. elegans CYPs in metabolizing eicosapentaenoic acid and arachidonic acid, whose metabolic products could serve as secondary messengers in various signaling pathways (Kulas et al., 2008). Alternatively, CYP-35A5 could directly metabolize AEA. Support for this hypothesis comes from earlier studies, however not in C. elegans, demonstrating that mammalian CYPs can metabolize AEA and its hydrolysis product arachidonic acid into bioactive compounds (HETEs and EETs; Bornheim et al., 1995; Snider et al., 2007, 2008; Chen et al., 2008; Stark et al., 2008), some of which can activate cannabinoid receptors (Chen et al., 2008).

If cyp-35A5 mutants respond homeostatically to lower fats by increasing endocannabinoids, why do cyp-35A1 mutants not respond in the same manner? First, lack of the CYP-35A1 protein appears to result in lower overall fat (Figure 2) and increases in both fatty acid desaturation and elongation gene expressions (Figure 5). These appear to suggest a role for CYP-35A1 in maintaining constitutive fat levels. In support of this hypothesis, cyp-35A1 gene expression does not respond to fat feeding while other cyp-35A1 family members do (Table 1). Moreover, endocannabinoid levels appear normal in cyp-35A1 mutants.

Conclusion

Taken together, these results show that the CYP-35A subfamily plays a part in the dynamic regulation of the variety of different fatty acid molecules in C. elegans. The lack of CYP-35A1 and CYP-35A5 decreases intestinal fat stores. However, the mechanism by which this is achieved may differ, as the transcriptional levels of fatty acid metabolism genes differ dramatically between these two mutants. Moreover, CYP-35A1 does not appear to respond transcriptionally to fat ingestion, whereas CYP-35A5 and other CYP-35 members consistently decrease gene expression. The lack of CYP-35A5 affects AEA levels. Taken with the modest changes in fatty acid profiles, these results suggests a stronger role for CYP-35A members in regulating fatty acid derived signaling molecules, rather than structural fatty acids, in C. elegans. In summary, these results demonstrate an important role for CYP-35A members in regulating fat metabolism and signaling molecules in C. elegans. These results thus provide a framework for future mechanistic studies to investigate fatty acid signaling in pharmacology or toxicology contexts using C. elegans. Finally, these findings provide a basis to predict toxicity in higher organisms including humans.

Authorization for the use of experimental animals: Use of genetically modified organisms (GMO) in this study was approved by the Finnish GMO authority (Reg. number 2/E/09).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online http://www.frontiersin.org/Predictive_Toxicity/10.3389/fphar.2011.00012/abstract

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health, for providing some of the worm strains used in this study. The Finnish Toxicology graduate school provided a fellowship (to Vuokko Aarnio) for this work to be undertaken. The Sigrid Juselius Foundation and Saastamoinen Foundation are gratefully acknowledged for providing additional financial support for this project. Members of the NordForsk Nordic C. elegans Researcher Network are acknowledged for helpful suggestions and discussion during various stages of this project.

References

- Aarnio V., Storvik M., Lehtonen M., Asikainen S., Reisner K., Callaway J., Rudgalvyte M., Lakso M., Wong G. (2010). Fatty acid composition and gene expression profiles are altered in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-1 mutant Caenorhabditis elegans. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 151, 318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amacher D. E. (2010). The effects of cytochrome P450 induction by xenobiotics of endobiotic metabolism in pre-clinical safety studies. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 20, 159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold C., Konkel A., Fischer R., Schunck W. H. (2010). Cytochrome P450-dependent metabolism of omega-6 and omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Pharmacol. Rep. 62, 536–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi K., Chang F. Y., Watts J. L., Fraser A. G., Kamath R. S., Ahringer J., Ruvkun G. (2003). Genome-wide RNAi analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans fat regulatory genes. Nature 421, 268–272 10.1038/nature01279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asikainen S., Rudgalvyte M., Heikkinen L., Louhiranta K., Lakso M., Wong G., Nass R. (2010). Global microRNA expression profiling of Caenorhabditis elegans Parkinson's disease models. J. Mol. Neurosci. 41, 210–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awumey E. M., Hill S. K., Diz D. I., Bukoski R. D. (2008). Cytochrome P450 metabolites of 2-arachidonoyl glycerol play a role in Ca2+-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 294, H2362–H2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benenati G., Penkov S., Müller-Reichert T., Entchev E. V., Kurzchalia T. V. (2009). Two cytochrome P450s in Caenorhabditis elegans are essential for the organization of eggshell, correct execution of meiosis and the polarization of embryo. Mech. Dev. 126, 382–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornheim L. M., Kim K. Y., Chen B., Correia M. A. (1995). Microsomal cytochrome P450-mediated liver and brain anandamide metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 50, 677–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani B. P. S., Kumar S., Subramaniam J. R. (2008). Development and evaluation of an in vivo assay in Caenorhabditis elegans for screening of compounds for their effect on cytochrome P450 expression. J. Biosci. 33, 269–277 10.1007/s12038-008-0044-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-K., Chen J., Imig J. D., Wei S., Hachey D. L., Jagadeesh Setti Guthi J. S., Falck J. R., Capdevila J. H., Harris R. C. (2008). Identification of novel endogenous cytochrome P450 arachidonate metabolites with high affinity for cannabinoid receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24514–24524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D., Sandoval D. A., Olivieri M., Prodi E., D'Alessio D. A., Woods S. C., Seeley R. J., Obici S. (2009). Food intake-independent effects of CB1 antagonism on glucose and lipid metabolism. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17, 1641–1645 10.1038/oby.2009.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elphick M. R., Egertová M. (2001). The neurobiology and evolution of cannabinoid signaling. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356, 381–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fer M., Dreano Y., Lucas D., Corcos L., Salaun J. P., Berthou F., Amet Y. (2008). Metabolism of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids by recombinant human cytochromes P450. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 471, 116–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyereisen R. (2006). Evolution of insect P450. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 1252–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicek P., Aken B. L., Ballester B., Beal K., Bragin E., Brent S., Chen Y., Clapham P., Coates G., Fairley S., Fitzgerald S., Fernandez-Banet J., Gordon L., Gräf S., Haider S., Hammond M., Howe K., Jenkinson A., Johnson N., Kähäri A., Keefe D., Keenan S., Kinsella R., Kokocinski F., Koscielny G., Kulesha E., Lawson D., Longden I., Massingham T., McLaren W., Megy K., Overduin B., Pritchard B., Rios D., Ruffier M., Schuster M., Slater G., Smedley D., Spudich G., Tang Y. A., Trevanion S., Vilella A., Vogel J., White S., Wilder S. P., Zadissa A., Birney E., Cunningham F., Dunham I., Durbin R., Fernández-Suarez X. M., Herrero J., Hubbard T. J., Parker A., Proctor G., Smith J., Searle S. M. (2010). Ensembl's 10th year. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D557–D562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerisch B., Weitzel C., Kober-Eisermann C., Rottiers V., Antebi A. (2001). A hormonal signaling pathway influencing C. elegans metabolism, reproductive development, and life span. Dev. Cell 1, 841–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh O. (1998). Divergent structures of Caenorhabditis elegans cytochrome P450 genes suggest the frequent loss and gain of introns during the evolution of nematodes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 1447–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa M., Sakamoto K. (2010). Polyunsaturated fatty acids are involved in regulatory mechanism of fatty acid homeostasis via daf-2/insulin signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 323, 183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia K., Albert P. S., Riddle D. L. (2002). DAF-9, a cytochrome P450 regulating C. elegans larval development and adult longevity. Development 129, 221–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan T., Djaouti L., Demixieux L., Gresti J., Vergès B., Degrace P. (2010). CB1 antagonism exerts specific molecular effects on visceral and subcutaneous fat and reverses liver steatosis in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes 59, 926–934 10.2337/db09-1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S., Fraser A. G., Dong Y., Poulin G., Durbin R., Gotta M., Kanapin A., Le Bot N., Moreno S., Sohrmann M., Welchmann D. P., Ziperlen P., Ahringer J. (2003). Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421, 231–237 10.1038/nature01278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniazeva M., Crawford Q. T., Seiber M., Wang C.-Y., Han M. (2004). Monomethyl branched-chain fatty acids play an essential role in Caenorhabditis elegans development. PLoS Biol. 2, e257. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkel A., Schunck W.-H. (2010). Role of cytochrome P450 enzymes in the bioactivation of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1814, 210–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulas J., Schmidt C., Rothe M., Schunk W.-H., Menzel R. (2008). Cytochrome P450-dependent metabolism of eicosapentaenoic acid in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 472, 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen M., Reisner K., Auriola S., Wong G., Callaway J. (2008). Mass-spectrometric identification of anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol in nematodes. Chem. Biodivers. 5, 2431–2441 10.1002/cbdv.200890208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C (T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccarrone M., Gasperi V., Valeria Catani M., Diep T. A., Dainese E., Hansen H. S., Avigliano L. (2010). The endocannabinoid system and its relevance for nutrition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 30, 423–440 10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias I., Di Marzo V. (2007). Endocannabinoids and the control of energy balance. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 18, 27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPartland J. M., Matias I., Di Marzo V., Glass M. (2006). Evolutionary origins of the endocannabinoid system. Gene 370, 64–74 10.1016/j.gene.2005.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel R., Bogaert T., Achazi R. (2001). A systematic gene expression screen on Caenorhabditis elegans cytochrome P450 genes reveals CYP35 as strongly xenobiotic inducible. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 395, 158–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel R., Rödel M., Kulas J., Steinberg C. E. W. (2005). CYP35: Xenobiotically induced gene expression in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 438, 93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel R., Yeo H. L., Rienau S., Li S., Steinberg C. E. W., Stürzenbaum S. R. (2007). Cytochrome P450s and short-chain dehydrogenases mediate the toxicogenomic response of PCB52 in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Mol. Biol. 370, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullaney B. C., Ashrafi K. (2008). C. elegans fat storage and metabolic regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 474–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D. R. (2003). Comparison of P450s from human and fugu: 420 million years of vertebrate P450 evolution. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 409, 18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke E. J., Soukas A. A., Carr C. E., Ruvkun G. (2009). C. elegans major fats are stored in vesicles distinct from lysosome-related organelles. Cell Metab. 10, 430–435 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkonen O. (2010). Predictive toxicity: grand challenges. Front. Pharmacol. 1: 3. 10.3389/fphar.2010.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappeleye C. A., Tagawa A., Le Bot N., Ahringer J., Aroian R. W. (2003). Involvement of fatty acid pathways and cortical interaction of the pronuclear complex in Caenorhabditis elegans embryonic polarity. BMC Dev. Biol. 3, 8. 10.1186/1471-213X-3-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert K., Menzel R. (2005). Expression profiling of five different xenobiotics using a Caenorhabditis elegans whole-genome microarray. Chemosphere 61, 229–237 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.01.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh J. Y., Jung I.-H., Lee J.-Y., Choi J. (2007). Toxic effects of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate on mortality, growth, reproduction and stress-related gene expression in the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicology 237, 126–133 10.1016/j.tox.2007.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rual J. F., Ceron J., Koreth J., Hao T., Nicot A. S., Hirozane-Kishikawa T., Vandenhaute J., Orkin S. H., Hill D. E., van den Heuvel S., Vidal M. (2004). Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 14, 2162–2168 10.1101/gr.2505604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder L. K., Kremer S., Kramer M. J., Currie E., Kwan E., Watts J. L., Lawrenson A. L., Hermann G. J. (2007). Function of the Caenorhabditis elegans ABC transporter PGP-2 in the biogenesis of a lysosome-related fat storage organelle. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 995–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz D., Kisselev P., Ericksen S. S., Szklarz G. D., Chernogolov A., Honeck H., Schunck W. H., Roots I. (2004). Arachidonic and eicosapentaenoic acid metabolism by human CYP1A1: highly stereoselective formation of 17(R),18(S)-epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid. Biochem. Pharmacol. 67, 1445–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider N. T., Kornilov A. M., Kent U. M., Hollenberg P. F. (2007). Anandamide metabolism by human liver and kidney microsomal cytochrome P450 enzymes to form hydroxyeicosatetraenoic and epoxyeicosatrienoic acid ethanolamides. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 321, 590–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider N. T., Sikora M. J., Sridar C., Feuerstein T. J., Rae J. M., Hollenberg P. F. (2008). The endocannabinoid anandamide is a substrate for the human polymorphic cytochrome P450 2D6. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 327, 538–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider N. T., Walker V. J., Hollenberg P. F. (2010). Oxidation of the endogenous cannabinoid arachidonoyl ethanolamide by the cytochrome P450 monooxygenases: physiological and pharmacological implications. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 136–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnichsen B., Koski L. B., Walsh A., Marschall P., Neumann B., Brehm M., Alleaume A. M., Artelt J., Bettencourt P., Cassin E., Hewitson M., Holtz C., Khan M., Lazik S., Martin C., Nitzsche B., Ruer M., Stamford J., Winzi M., Heinkel R., Roder M., Finell J., Hantsch H., Jones S. J., Jones M., Piano F., Gunsalus K. C., Oegema K., Gonczy P., Coulson A., Hyman A. A., Echeverri C. J. (2005). Full-genome RNAi profiling of early embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 434, 462–469 10.1038/nature03353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukas A. A., Kane E. A., Carr C. E., Melo J. A., Ruvkun G. (2009). Rictor/TORC2 regulates fat metabolism, feeding, growth, and life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 23, 496–511 10.1101/gad.1775409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark K., Dostalek M., Guengerich F. P. (2008). Expression and purification of orphan cytochrome P450 4X1 and oxidation of anandamide. FEBS J. 275, 3706–3717 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06518.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubert S., Van Gilst M. R., Hansen M., Yamamoto K. R. (2006). A mediator subunit, MDT-15, integrates regulation of fatty acid metabolism by NHR-49-dependent and independent pathways in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 20, 1137–1149 10.1101/gad.1395406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. H. (2007). Rapid birth-death evolution specific to xenobiotic cytochrome P450 genes in vertebrates. PLoS Genet. 3, e67. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gilst M. R., Hadjivassiliou H., Jolly A., Yamamoto K. R. (2005a). Nuclear hormone receptor NHR-49 controls fat consumption and fatty acid composition in C. elegans. PLoS Biol. 3, e53. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gilst M. R., Hadjivassiliou H., Yamamoto K. R. (2005b). A Caenorhabditis elegans nutrient response system partially dependent on nuclear receptor NHR-49. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 134496–113501 10.1073/pnas.0506234102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts J. (2009). Fat synthesis and adiposity regulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 20, 58–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts J. L., Browse J. (2000). A palmitoyl-CoA-specific (9 fatty acid desaturase from Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 272, 263–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts J. L., Browse J. (2002). Genetic dissection of polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5854–5859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. O., Box A. C., Xu N., Le Men J., Yu J., Guo F., Trimble R., Yi Mak H. (2010). Genetic and dietary regulation of lipid droplet expansion in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4640–4645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt P. M., Petersson J., Andersson D. A., Chuang H., Sørgård M., Di Marzo V., Julius D., Högestätt E. D. (1999). Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature 400, 452–457 10.1038/22761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]