Abstract

Investigations into the evolutionary history of the common chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes, have produced inconsistent results due to differences in the types of molecular data considered, the model assumptions employed, and the quantity and geographical range of samples used. We amplified and sequenced 24 complete P. troglodytes mitochondrial genomes from fecal samples collected at multiple study sites throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Using a “relaxed molecular clock,” fossil calibrations, and 12 additional complete primate mitochondrial genomes, we analyzed the pattern and timing of primate diversification in a Bayesian framework. Our results support the recognition of four chimpanzee subspecies. Within P. troglodytes, we report a mean (95% highest posterior density [HPD]) time since most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of 1.026 (0.811–1.263) Ma for the four proposed subspecies, with two major lineages. One of these lineages (tMRCA = 0.510 [0.387–0.650] Ma) contains P. t. verus (tMRCA = 0.155 [0.101–0.213] Ma) and P. t. ellioti (formerly P. t. vellerosus; tMRCA = 0.157 [0.102–0.215] Ma), both of which are monophyletic. The other major lineage contains P. t. schweinfurthii (tMRCA = 0.111 [0.077–0.146] Ma), a monophyletic clade nested within the P. t. troglodytes lineage (tMRCA = 0.380 [0.296–0.476] Ma). We utilized two analysis techniques that may be of widespread interest. First, we implemented a Yule speciation prior across the entire primate tree with separate coalescent priors on each of the chimpanzee subspecies. The validity of this approach was confirmed by estimates based on more traditional techniques. We also suggest that accurate tMRCA estimates from large computationally difficult sequence alignments may be obtained by implementing our novel method of bootstrapping smaller randomly subsampled alignments.

Keywords: evolution, chimpanzee, phylogeny, relaxed molecular clock, Yule, coalescent

Introduction

Primate evolution is a topic of widespread interest and frequent investigation in large part because of a desire to understand the details and context of human evolution. Humans are most closely related to the two species comprising the genus Pan: Pan troglodytes (the common chimpanzee) and P. paniscus (the bonobo). Deliberation over the appropriate classification of P. troglodytes into biologically relevant groups is ongoing (Gonder et al. 2006), and the timing of significant divergence events within the species is not resolved (e.g., Won and Hey 2005; Becquet et al. 2007; Hey 2010). An accurate timescale of evolution of our closest relatives is fundamental to investigating a range of important questions, from the emergence of pathogens to the nature of the adaptive changes that have occurred within humans and apes.

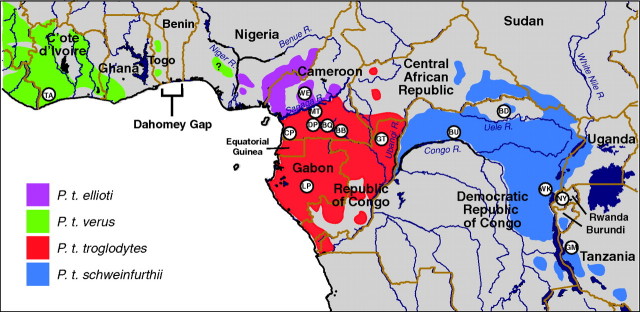

Pan troglodytes was traditionally classified into three populations or subspecies: the western (P. t. verus), central (P. t. troglodytes), and eastern (P. t. schweinfurthii) chimpanzees (Hill 1969; Morin et al. 1992). Analyses of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from specimens collected from previously unsampled regions have pointed to a fourth genetically defined group, P. t. vellerosus (Gonder et al. 1997, 2006), which has since been renamed P. t. ellioti (Oates et al. 2009). This group forms a sister clade to P. t. verus and inhabits regions of Cameroon and Nigeria (fig. 2). With rare exceptions (Gonder et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2008), the range of P. t. ellioti is believed to be separated from that of P. t. troglodytes by the Sanaga River in central Cameroon.

FIG. 2.

Chimpanzee fecal sample collection sites in sub-Saharan Africa. International borders are shown in brown. Ranges of the four proposed chimpanzee subspecies are highlighted in color. The question mark (?) west of the lower Niger River indicates that the limited mtDNA sequences available to date from this region have clustered phylogenetically with P. t. verus (Gagneux et al. 2001). Collection sites were located in Cameroon (BB, BQ, CP, DP, MT, and WE), Cote d’Ivoire (TA), Republic of Congo (GT), Democratic Republic of Congo (BD, BU, WK), Gabon (LP), Rwanda (NY), and Tanzania (GM), as reported previously (Liu et al. 2008).

A recent population genetics study of nuclear markers in common chimpanzees and bonobos found no evidence for a distinct P. t. ellioti population cluster, though the authors point out that this could reflect a lack of statistical power or inadequate sampling (Becquet et al. 2007). In a previous study (Liu et al. 2008), we considered chimpanzee diversification indirectly by analyzing ancient coevolutionary host/pathogen relationships. We sequenced naturally occurring strains of the chimpanzee-infecting simian foamy virus (SFVcpz) and found that the virus did, in fact, cluster into four distinct clades. The mtDNA-defined subspecies of each strain’s host was determined, revealing that each chimpanzee subspecies harbored a distinct SFVcpz lineage, although virus and host mtDNA branching patterns were not identical. The dates of ancestry of these subspecies are not well resolved, and mtDNA-based estimates have yet to be contributed.

We sequenced 24 complete mitochondrial sequences from fecal samples collected in the wild across the common chimpanzee’s range in sub-Saharan Africa, dramatically increasing the number of complete P. troglodytes mtDNA genomes available for study. Until now, complete mtDNA genomes were only available for one chimpanzee subspecies, P. t. verus. We included 12 previously published primate mitochondrial genomes in our study, allowing us to carry out a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis from the within-species level of P. troglodytes to the level of the Simiiformes (New World monkeys, Old World monkeys, and Great Apes) as a whole.

Using a “relaxed molecular clock” and fossil-based calibrations, we exploited this unusually extensive and signal-rich data set to test multiple approaches designed to deal with the problem of analyzing alignments containing both intraspecific and interspecific sequences. All our approaches produced consistent results. We discuss the broad applicability of these approaches and their potential to improve the efficiency of analyses of large sequence alignments.

Materials and Methods

Chimpanzee Fecal Samples

In a previous study of SFVcpz molecular epidemiology, we analyzed 40 fecal samples from captive chimpanzees and 732 fecal samples from wild-living chimpanzees sampled at 25 field sites across the four proposed subspecies ranges in sub-Saharan Africa (Santiago et al. 2003; Worobey et al. 2004; Keele et al. 2006; Van Heuverswyn et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2008). A 498-bp mtDNA D loop fragment was amplified from all these samples to confirm their species and subspecies origin, and a subset (n = 24) was subsequently selected for complete mtDNA genome amplification and sequencing. Of these, 21 samples represented wild chimpanzees from study sites (fig. 2) in Cameroon (BB, BQ, CP, DP, MT, and WE), Cote d’Ivoire (TA), Republic of Congo (GT), Democratic Republic of Congo (BD, BU, and WK), Gabon (LP), Rwanda (NY), and Tanzania (GM). Three others were acquired from captive chimpanzees housed at a Cameroonian sanctuary (SA) and the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (YK) in the United States. There is a strong possibility that two samples (WE449 and WE451) originated from the same individual; alternatively, they originated from two close maternal relatives.

Amplification of Full-Length Mitochondrial Genome Equivalents from Chimpanzee Fecal DNA

Fecal DNA was extracted using the QIAamp Stool DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as described previously (Keele et al., 2006). Briefly, 0.5 ml of fecal RNAlater mixture was resuspended in stool lysis buffer, clarified by centrifugation, reacted with an InhibitEx tablet, treated with proteinase K, and passed through a DNA-binding column. Bound DNA was reconstituted in 80 μl elution buffer.

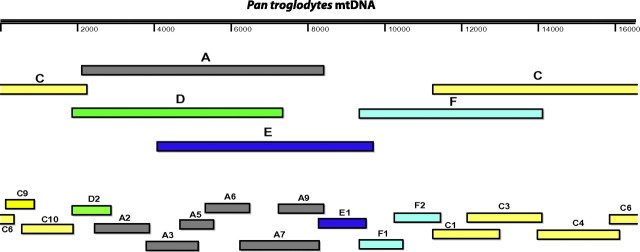

Primers used to amplify chimpanzee mtDNA were designed based on a previously published chimpanzee mtDNA sequence (GenBank accession number: D38113) and are listed in Table 1. Mitochondrial genome equivalents were derived as overlapping fragments using nested polymerase chain reaction amplification. First round primers amplified 5 fragments (A, C, D, E, and F), ranging in length from 4.7 to 7.5 kb, using the following conditions: hot start at 94 °C 2 min; 15 cycles of 94 °C 10 s, 45 °C 30 s, and 68 °C 7 min; followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C 10 s, 48 °C 30 s, and 68 °C 7 min with autoextension of 15 s per cycle; and final extension of 68 °C 7 min. Second round primers amplified 16 fragments (A2, A3, A5, A6, A7, A9, C1, C3, C4, C6, C9, C10, D2, E1, F1, and F2) ranging in length from 0.7 to 2.1 kb using the following conditions: hotstart at 94 °C 2 min; 45 cycles of 94 °C 10 s, 52 °C 30 s, and 68 °C 2 min; and final extension of 68 °C 7 min. Amplicons were gel purified (Qiagen) and sequenced directly without interim cloning. Sequences were assembled into contigs using Sequencher version 4.6 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI). The position of the various amplicons is shown in figure 1. The 24 complete mitochondrial genome sequences are available from GenBank under accession numbers HM068570–HM068593.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide Primers Used to Amplify Mitochondrial Genomic Equivalents from Chimpanzee Fecal DNA.

| Forward Primerb | Reverse Primerb | Sizec | |

| Fragment (first round PCR)a | |||

| A | Ptrg2110U: 5′-TGAAGAGGCGGGCATAACATA-3′ | Ptrg8422L; 5′-GACGTACGGCTAAGGCTATTGG-3′ | 6,311 |

| C | Ptrg11253U: 5′-GACTCCTGGCAAGCCTCGCTAA-3′ | Ptrg2254L; 5′-GTTGTGCTCCGAGGTCGC-3′ | 7,556 |

| D | Ptrg1857U; 5′-ATGCCCACAAGGAAAGGT-3′ | Ptrg7355L; 5′-AAGATTAGCCCGCCGTAG-3′ | 5,499 |

| E | Ptrg4072U; 5′-CACAAGCAACTGCGTCCAT-3′ | Ptrg9714L; 5′-GTAGGGCTCAAGGTAAGG-3′ | 5,643 |

| F | Ptrg9335U; 5′-CGCCGCCTGATACTGRCA-3′ | Ptrg14120L; 5′-TGGTCGTGGTTGTAGTCC-3′ | 4,786 |

| Fragment (second round PCR)a | |||

| A2 | Ptrg2440U; 5′-CGCTATTAAAGGTTCGTTTG-3′ | Ptrg3890L; 5′-ATTAGTACGGGAAGGGTRTAAC-3′ | 1,429 |

| A3 | Ptrg3791U; 5′-TCCGTGCCACCTATCACA-3′ | Ptrg5161L; 5′-TGCGGCGGGAGAAGTAGATTGA-3′ | 1,371 |

| A5 | Ptrg4664U; 5′-CTTCTTACCCAAATGAGTTATC-3′ | Ptrg5556L; 5′-CCAAAGCCTCCGATTAT-3′ | 893 |

| A6 | Ptrg5323U; 5′-GTTCACCGACCGCTGACT-3′ | Ptrg6495L; 5′-CCTCCTATGATGGCGAATACAG-3′ | 1,473 |

| A7 | Ptrg6229U; 5′-CTATTTCACCTCCGCTACCA-3′ | Ptrg8308L; 5′-TAGTCTTAAAGCGAAAGCCTAT-3′ | 2,080 |

| A9 | Ptrg7233U; 5′-CCTACCATCCCTGCGTAT-3′ | Ptrg8422L; 5′-GACGTACGGCTAAGGCTATTGG-3′ | 1,190 |

| C1 | Ptrg11253U; 5′-GACTCCTGGCAAGCCTCGCTAA-3′ | Ptrg13001; 5′-GTGGCGATGAGAGTAATAGATA-3′ | 1,749 |

| C3 | Ptrg12146U: 5′-TAGTCACCGCTAACAACCTA-3′ | Ptrg14105L; 5′-TCCGTGCGAGAATAATGACATA-3′ | 1,960 |

| C4 | Ptrg13976U; 5′-CCAACTACACCACTAACAA-3′ | Ptrg16123L; 5′-TCAAAGACAGATACTGCGACAT-3′ | 2,148 |

| C6 | Ptrg15851U; 5′-AGTGACTCTCCTCGCTCC-3′ | Ptrg358L; 5′-CGCCGGTTTCTATTGAC-3′ | 1,062 |

| C9 | Ptrg126U; 5′-CATCCCCGCCCCGTGAGT-3′ | Ptrg886L; 5′-AGGGCCCTGTTCAACTAAGCAC-3′ | 761 |

| C10 | Ptrg547U; 5′-TGCTCGCCAGAACACTAC-3′ | Ptrg1903L; 5′-GATTTGCCGAGTTCCTTT-3′ | 1,357 |

| D2 | Ptrg1857U; 5′-ATGCCCACAAGGAAAGGT-3′ | Ptrg2884L; 5′-TTATGGCGTCAGCGAARG-3′ | 1,028 |

| E1 | Ptrg8273U; 5′-CAGGCGCAGTAGTCATAG-3′ | Ptrg9524L; 5′-TAGTAGGGCTAGAAGGGTATTG-3′ | 1,252 |

| F1 | Ptrg9335U; 5′-CGCCGCCTGATACTGRCA-3′ | Ptrg10483L; 5′-GAGGGAAATTAGCATGGAGA-3′ | 1,149 |

| F2 | Ptrg10244U; 5′-GCCACCTATCCAACGAA-3′ | Ptrg11468L; 5′-TGAATGAGGGCTTTATGCTATT-3′ | 1,047 |

Note.—a See figure X for fragment position within the P. troglodytes mitochondrial (mt) genome.

Primers were designed according to previously published chimpanzee mtDNA sequences (GenBank accession number: D38113) with minor modifications.

Size of PCR fragments (in base pairs).

FIG. 1.

Amplification of full-length mitochondrial genomic equivalents from chimpanzee fecal DNA. Amplicons are shown in relation to a previously published chimpanzee mitochondrial genome sequence (Genbank accession number: D38113) and are labeled as shown in Table 1.

Primate mtDNA Sequence Alignments

The 24 assembled mtDNA genomes represent the four chimpanzee subspecies as follows: P. t. schweinfurthii (6), P. t. troglodytes (12), P. t. ellioti (4), and P. t. verus (2). Twelve previously characterized mtDNA genomes were included in the alignment, as well, including two P. t. verus sequences (GenBank accession numbers X93335 and NC_001643) and ten sequences from other primate species: P. paniscus (NC_001644), Homo sapiens (NC_001807), Gorilla gorilla (NC_001645), Gorilla gorilla gorilla (NC_011120), Pongo abelii (NC_002083), Pongo pygmaeus (NC_001646), Hylobates lar (NC_002082), Macaca sylvanus (NC_002764), Papio hamadryas (NC_001992), and the New World monkey Cebus albifrons (NC_002763).

The 36 complete mtDNA genomes were aligned with the ClustalW online server (Larkin et al. 2007), and the alignment was manually refined using Se-Al (A. Rambaut, http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/seal/). Following the approach used by Raaum et al. (2005), the alignment was pared down to a concatenation of the 12 guanine-rich protein-coding genes located on the mitochondrial genome’s heavy strand. Insertions and deletions were adjusted manually with codon positions conserved, and stop codons and major gaps were deleted, resulting in a final alignment of 10,743 bp. This alignment is hereby referred to as the “chimpanzee-plus” alignment. A subset of this alignment containing only the 26 P. troglodytes sequences is named the “chimpanzee-only” alignment.

One hundred additional alignments of 14 sequences apiece were generated from the chimpanzee-plus alignment, each containing the ten non-P. troglodytes genomes and one randomly sampled sequence from each of the four P. troglodytes subspecies. These alignments are hereby referred to as the “bootstrapped-chimpanzee” alignments and were analyzed to test the validity of our chimpanzee-plus analyses (see below). The bootstrapped-chimpanzee alignments were analyzed by more traditional means than our chimpanzee-plus alignment, which was analyzed with a newly devised approach.

Phylogenetic Analyses

To infer mtDNA phylogenies, we used the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (BMCMC) approach implemented in BEAST v1.4.8 (Drummond and Rambaut 2007). BEAST can use a relaxed molecular clock, which, by allowing evolutionary rates to vary from branch to branch, has been shown to improve the quality of time to most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) estimates over those obtained under the strict assumption of a constant evolutionary rate across the tree (Drummond et al. 2006). All BEAST runs were performed under an uncorrelated lognormal relaxed molecular clock model using the SRD06 model of nucleotide substitution, which partitions nucleotide data by codon position and allows third codon positions to differ from positions 1 and 2 in transition bias, substitution rate, and shape of the gamma distribution of rate heterogeneity (Shapiro et al. 2006).

The chimpanzee-plus and chimpanzee-only BEAST runs were performed twice each for 10 million generations. Each of the 100 bootstrapped-chimpanzee alignments was run once for 5 million generations. For all analyses, the independent runs were then combined (after discarding 10% of the generations from each run as burnin) to estimate posterior values. Maximum clade credibility (MCC) trees were identified and annotated using TreeAnnotator v1.4.8 (Drummond and Rambaut 2007). Nodes with posterior probabilities exceeding 90% (P > 0.90) were identified, and tMRCA estimates were denoted (in Ma) by mean values and 95% highest posterior density (HPD).

The rate of evolution in the chimpanzee-plus and bootstrapped-chimpanzee analyses were calibrated by applying lognormally distributed priors about robustly supported estimates of divergence events at three internal nodes (Raaum et al. 2005): Old World monkey–hominoid (23 Ma), orangutan–African ape (14 Ma), and chimpanzee–human (6 Ma). When incorporating fossil evidence, the sampling of calibration dates from lognormally distributed priors is preferable to normal distributions or fixed-point priors. Given the shape of a lognormal curve, values representing times from the more distant past are sampled more frequently than those representing times in the more recent past. This accounts for the likelihood that actual divergence events precede the fossilization of individuals from daughter lineages (Ho 2007). We used lognormal calibration distributions with lognormal means of zero and lognormal standard deviations of 0.56, and we offset these distributions by 22 Ma (Old World monkey–hominoid), 13 Ma (orangutan–African ape), and 5 Ma (chimpanzee–human). This ensured that the median values of the sampled distributions were equal to and the mean values were slightly greater than the respective 23, 14, and 6 Ma point calibrations used by Raaum et al. (2005).

In a phylogenetic study of five bovine species, Ho et al. (2008) applied separate population-level coalescent priors to each of the species. For the deep internal portion of the tree connecting the species, they used an uninformative tree prior. Because the chimpanzee-plus alignment contains a combination of interspecific sequences and intraspecific (common chimpanzee) sequences, we adapted this approach (2008) and implemented Yule speciation prior across the tree but with separate coalescent priors applied to each of the four P. troglodytes subspecies clades. Initially, we performed two separate analyses: one with all four subspecies clades assigned a constant demographic growth rate prior and one with an exponential growth rate prior applied to all. The 95% HPD of the exponential growth rate excluded zero in the P. t. schweinfurthii and P. t. troglodytes clades, thus rejecting a constant population growth rate for those subspecies. Therefore, we performed a third analysis with a combination of constant (P. t. ellioti and P. t. verus) and exponential (P. t. schweinfurthii and P. t. troglodytes) growth rate priors. We report the results of the third analysis, though we note that the results from all three of the above analyses were statistically indistinguishable.

The bootstrapped-chimpanzee BEAST runs were devised to test semi-independently the validity of the mixed-Yule/coalescent approach that we implemented (described above) for the chimpanzee-plus alignment. These runs were calibrated with the same three internal node priors but were executed in a more conventional manner under a Yule speciation tree prior only. The 100 bootstrapped-chimpanzee alignments included no intrapopulational data; each alignment contained only one sequence per species or subspecies, making a Yule speciation model an appropriate choice. BEAST input files for all three alignments are available at the Dryad Digital Repository (http://datadryad.org, DOI:10.5061/dryad.1862).

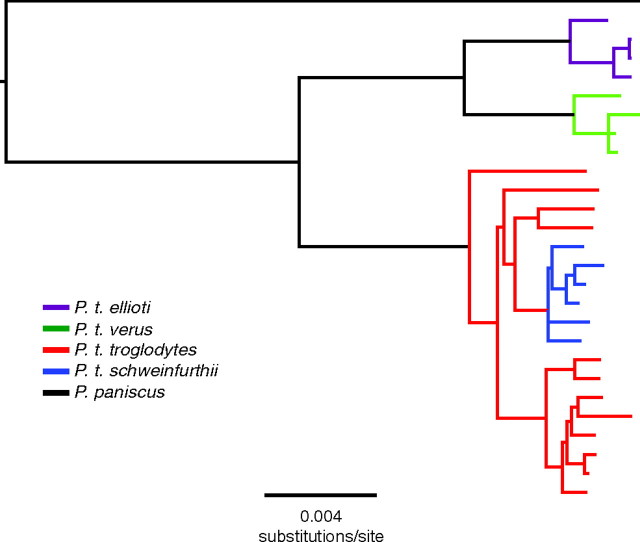

We also examined chimpanzee evolution without imposing a molecular clock by using MrBayes v3.1 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001) to run a BMCMC analysis (with gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity among sites and a generalized time reversible nucleotide substitution model) of the P. paniscus sequence and the 26 P. troglodytes sequences. Four independent runs of 10 million steps each were completed, with a sampling interval of every 1,000 steps and a 10% burnin. The unrooted 50% majority-rule consensus tree was calculated, with branch lengths representing the number of substitutions per site, as opposed to time.

For all BEAST and MrBayes analyses, convergence and proper mixing, with estimated sample sizes exceeding 200, were confirmed by examination with Tracer v1.4 (A. Rambaut & A. J. Drummond, http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/). The AWTY graphical exploration software (Wilgenbusch et al., http://ceb.csit.fsu.edu/awty) was also used to confirm convergence. For added assurance, we performed two additional runs of our chimpanzee-plus BEAST analysis to allow us to compare a total of four independent runs with Tracer and AWTY. The addition of two more independent BEAST runs produced qualitatively identical results. We also ran our BEAST analyses with no sequence data to verify that our tMRCA estimates are not a result of priors alone as opposed to sequence information. Finally, for our chimpanzee-plus alignment, we used PhyML (http://www.phylogeny.fr) to produce a maximum likelihood–based phylogeny reconstruction for comparison with those of our BMCMC-based BEAST and MrBayes analyses.

Results and Discussion

In this study, we performed the first mtDNA-based analysis of the timing and topology of diversification within the P. troglodytes lineage using 24 newly derived full-length chimpanzee mitochondrial genomes. By simultaneously incorporating speciation and population-level demographic parameters into our analyses, we also obtained tMRCA estimates of major primate lineages back to the most recent common ancestor preceding the split of New World monkeys from Old World monkeys and the Great Apes.

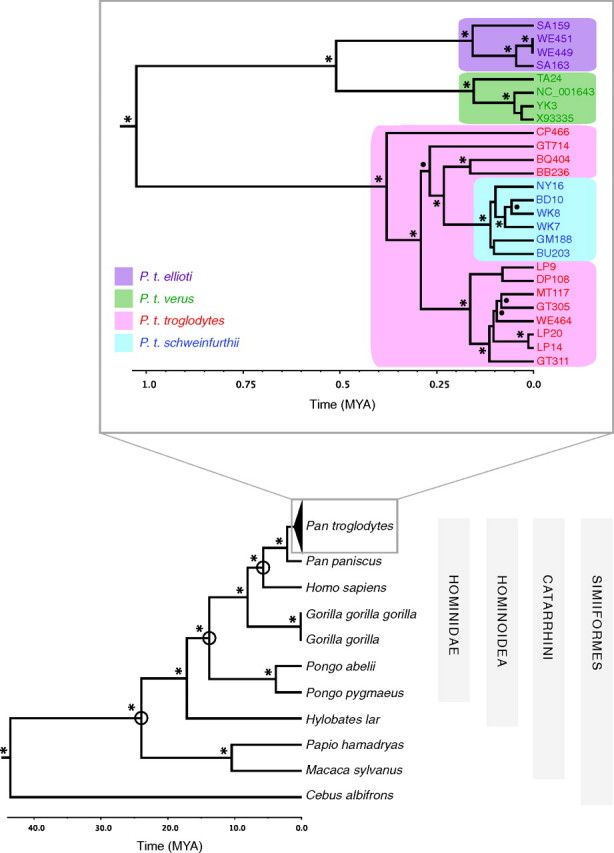

We inferred the phylogenies for our chimpanzee-plus mtDNA alignment (fig. 3) and bootstrapped-chimpanzee alignments (not shown) in a BMCMC framework. The bootstrapped-chimpanzee approach utilized a standard Yule speciation prior because each run of the analysis consisted of only one sequence per species or subspecies. The chimpanzee-plus analysis was more complex because it combined a Yule speciation prior across the tree with separate population-level coalescent priors on each chimpanzee subspecies clade. The resulting between-species tMRCA estimates from these two approaches are statistically indistinguishable (Table 2), thus supporting the utility of the mixed-model approach, first described by Ho et al. (2008), for interspecific analyses. Though some discrepancies exist in side-by-side comparisons with individual studies, our interspecific tMRCA estimates fall within the ranges of existing nuclear- and mtDNA-based estimates of primate divergence dates (e.g., Glazko and Nei 2003; Satta et al. 2004; Raaum et al. 2005; Steiper and Young 2006; Hobolth et al. 2007). The topology resulting from our PhyML analysis of the chimpanzee-plus alignment revealed high node support and a topology matching that of our BMCMC results with or without a molecular clock imposed as expected (see Wertheim et al. 2010).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of the “chimpanzee-plus” mtDNA genomes alignment. mtDNA sequences (10,743 bp) were analyzed using the BMCMC approach in BEAST. The MCC tree is presented, with the Pan troglodytes clade shown boxed and enlarged. The subspecies of each sample was determined by mtDNA haplotype and is indicated by color. Posterior probabilities of well-supported nodes are represented by filled circles (90–99%) or asterisks (100%). Open circles indicate fossil-calibrated nodes. The P. t. troglodytes lineage is paraphyletic, and one of its samples (WE464) was collected in the P. t. ellioti range (see text). Specific details of the node date estimations are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

tMRCA Inferences from Primate mtDNA Alignments (in million years ago).

| tMRCA (95% HPD)a | |||

| Taxon | Chimpanzee-Plus Alignment | Bootstrapped-Chimpanzee Alignment | Chimpanzee-Only Alignment |

| Simiiformes | 43.533 (34.093–52.838) | 40.785 (31.159–50.501) | N/A |

| M. sylvanus–P. hamadryas | 10.454 (8.217–12.705) | 10.07 (7.837–12.407) | N/A |

| Catarrhini | 23.966 (22.327–26.228) | 23.867 (22.289–25.962) | N/A |

| Hominoidea | 17.166 (15.745–18.661) | 17.15 (15.706–18.766) | N/A |

| Hominidae | 13.807 (13.197–14.534) | 13.854 (13.186–14.537) | N/A |

| Pongo | 3.867 (2.835–4.928) | 3.805 (2.806–4.837) | N/A |

| Pan–Homo–Gorilla | 8.062 (7.093–9.165) | 8.189 (7.003–9.178) | N/A |

| G. gorilla–G. g. gorilla | 0.142 (0.083–0.199) | 0.145 (.081–0.208) | N/A |

| Pan–Homo | 5.751 (5.234–6.351) | 5.758 (5.216–6.367) | N/A |

| Pan | 2.149 (1.684–2.657) | 2.187 (1.621–2.663) | N/A |

| P. troglodytes | 1.026 (0.811–1.263) | 1.041 (0.770–1.288) | 1.002 (0.734–1.269) |

| P. t. troglodytes–P. t. schweinfurthii | 0.380 (0.296–0.476) | 0.339 (0.164–0.456) | 0.384 (0.235–0.536) |

| P. t. schweinfurthii | 0.111 (0.077–0.146) | N/A | 0.116 (0.066–0.171) |

| P. t. troglodytes | 0.380 (0.296–0.476) | N/A | 0.384 (0.235–0.536) |

| P. t. verus–P. t. ellioti | 0.510 (0.387–0.650) | 0.518 (0.340–0.679) | 0.508 (0.301–0.715) |

| P. t. ellioti | 0.157 (0.102–0.215) | N/A | 0.157 (0.083–0.242) |

| P. t. verus | 0.155 (0.101–0.213) | N/A | 0.148 (0.076–0.223) |

Note.—a Values in bold were sampled from prior distributions used to calibrate the tMRCA estimates (see text for more information).

Our study implements several key features that represent important advancements to the field, including 1) the estimation of within-chimpanzee subspecies tMRCAs based on mtDNA data, 2) the incorporation of a relaxed molecular clock and the lognormal distribution of fossil calibration dates, and 3) the fusion, into one analysis, of a species-level Yule prior across the entire primate tree with separate coalescent priors for the diversification of each chimpanzee subspecies. A study of this scope in chimpanzees was impossible before the addition of our 24 complete mitochondrial genomes. Until now, complete mtDNA genome sequences were available for only one of the four chimpanzee subspecies (P. t. verus). One conclusion to be drawn from this newly expanded collection of sequence data is the extent to which the mitochondrial genome of common chimpanzees evolves at a clock-like tempo (fig. 4), a finding that bolsters the utility of our approach for the dating of divergence events.

FIG. 4.

Midpoint-rooted tree demonstrating the “clock-like” nature of chimpanzee mtDNA evolution. Twenty-six P. troglodytes and one P. paniscus sequence were analyzed using the BMCMC approach in MrBayes. The majority-rule consensus tree is presented. Branch tips are colored by species or subspecies. Relationship patterns are the same as in figure 3, but sequence names are removed for clarity. All nodes are well supported, and posterior probabilities of all major nodes are 100%.

Our estimate of 2.149 (1.684–2.657) Ma for the tMRCA of P. troglodytes and P. paniscus falls within the date ranges from several previous single- and multi-locus studies (e.g., mtDNA: Horai et al. 1992; Raaum et al. 2005, Y-chromosome: Stone et al. 2002, and autosomal: Bailey et al. 1992; Yu et al. 2003; Becquet et al. 2007), but it is markedly older than the ∼0.9 Ma estimates yielded from others (e.g., X-chromosome: Kaessmann et al. 1999 and autosomal: Won and Hey 2005; Hey 2010). Two of the conflicting autosomal studies above (Yu et al. 2003; Won and Hey 2005) utilized the same 50-locus data set, with Won and Hey’s “isolation with migration” model producing the younger of the two estimates. Their model also leads to a much more recent within-P. troglodytes tMRCA (0.422 [0.255–0.629] Ma) than reported here (1.026 [0.811–1.263] Ma) or by Becquet et al. (2007) in another recent multi-locus autosomal study (0.84 [0.73–0.97] Ma). Despite this similarity, the subspecies-level tMRCAs resulting from the “average square distance” method employed by Becquet et al. are inconsistent with our BMCMC estimates. Nearly all their date ranges are considerably older than ours. It is important to note that discrepancies in dates, such as those mentioned above, could be due to the fact that the different methods provide temporal estimates of different events. In particular, the “isolation with migration” model is designed to estimate divergence times of the chimpanzee populations, whereas our BMCMC values provide estimates of the tMRCA of the mitochondrial gene tree.

The chimpanzee-plus analysis yielded a mean (95% HPD) tMRCA estimate for P. troglodytes of 1.026 (0.811–1.263) Ma (fig. 3), a value indistinguishable from that obtained from the bootstrapped-chimpanzee estimate (Table 2). This distribution was used to calibrate the root of the chimpanzee-only analysis. Again, all three of these approaches led to qualitatively identical estimations of chimpanzee subspecies divergence (Table 2), confirming that the mixed-Yule/coalescent approach of our chimpanzee-plus analysis is valid at the intraspecific level as well.

As demonstrated previously (e.g., Gagneux et al. 2001; Gonder et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2008), two major lineages are present within the common chimpanzee clade of the primate mtDNA tree (fig. 3). The oldest of these two major clades has a tMRCA of 0.510 (0.387–0.650) Ma and contains two monophyletic subspecies, P. t. verus and P. t. ellioti (formerly known as P. t. vellerosus), each with tMRCAs of ∼0.16 Ma. The tMRCA of the younger of the two major clades is estimated at 0.380 (0.296–0.476) Ma. Analyses by Gagneux et al. (2001) of over 300 mitochondrial haplotypes (415 bp from the control region, hypervariable region I) found no support for monophyly of P. t. troglodytes or P. t. schweinfurthii within this clade, leading the authors to question whether the lineage should instead be deemed a single subspecies. Our study finds P. t. schweinfurthii nested monophyletically, with a tMRCA of 0.111 (0.077–0.146), within the P. t. troglodytes lineage (fig. 3). This same topological pattern was reported earlier on the basis of shorter sequences (Liu et al. 2008).

The Sanaga River serves as a barrier between the two major chimpanzee lineages, with the P. t. ellioti/P. t. verus clade to the west and the P. t. troglodytes/P. t. schweinfurthii clade to the east. This barrier is not complete, however, as a P. t. troglodytes individual (WE464; fig. 3) was sampled north of the Sanaga River within the P. t. ellioti range in Cameroon (fig. 2) (see also Gonder et al. 2006). From the Sanaga River, the primary range of P. t. ellioti extends to the west into Nigeria. The primary range of its closest relative, P. t. verus, is hundreds of kilometers away, spreading westward from southern Ghana. Today, few populations have avoided extinction in between these two subspecies’ primary ranges, and they have not been well sampled. From a phylogeographic perspective, it is unclear what was responsible historically for maintaining the isolation between populations of P. t. verus and P. t. ellioti. The Dahomey Gap is a large stretch of dry forest extending across present-day Benin and Togo and into eastern Ghana. It is hypothesized to have played a major role as a geographic barrier helping to shape the distribution and diversification of many primates and other mammalian species in the region (Booth 1958) and has not been ruled out as a barrier for these two westernmost chimpanzee species. However, limited genetic evidence implicates the lower Niger River (in Nigeria) as a barrier between P. t. verus and P. t. ellioti. It appears as though only two chimpanzees have been mtDNA subtyped from the region in western Nigeria between the Dahomey Gap and the lower Niger River. These individuals cluster with P. t. verus, demonstrating that this species is not entirely absent to the east of the Dahomey Gap (Gonder and Disotell 2006).

Much easier to identify is the primary barrier between the P. t. troglodytes and P. t. schweinfurthii subspecies, which are separated by the Ubangi River in northwestern Democratic Republic of Congo. The nested position of P. t. schweinfurthii within the P. t. troglodytes clade indicates that P. t. troglodytes was established as a subspecies for some time (∼380,000 years ago), likely covering much of its existing western equatorial range. Only later (∼100,000 years ago), does it appear that the incipient P. t. schweinfurthii lineage was isolated from the rest of its population by the Ubangi River, leading to its eventual expansion across the continent to the east as far as Uganda and Tanzania.

Based on mitochondrial data alone, it is appropriate to designate P. t. ellioti as a subspecies, especially if P. t. schweinfurthii remains classified as its own subspecies rather than assigning this lineage P. t. troglodytes nomenclature like the rest of the clade within which it is nested. The subspecies’ ranges are, for the most part, geographically distinct, and molar morphometric data identify four chimpanzee subunits that correspond to the four proposed subspecies (Pilbrow 2006). Phylogenetic analysis of chimpanzee-infecting viruses also supports this classification. SFV strains fall into four distinct clades, with each clade’s viruses infecting wild chimpanzees of the same subspecies (Liu et al. 2008). Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), on the other hand, is known to infect only two chimpanzee subspecies, P. t. schweinfurthii and P. t. troglodytes. Further indication of the isolation of P. t. schweinfurthii from P. t. troglodytes is the finding that their SIVs fall into distinct clades on the chimpanzee and monkey SIV phylogenetic tree, and only strains from one of the two chimpanzee SIVs (those from P. t. troglodytes) are known to have made the cross-species transition to parent lineages of HIV (Keele et al. 2006).

Phylogenetic inferences based on mitochondrial sequences—even complete mitochondrial genomes—are based on only a single, maternally inherited nonrecombining locus with a relatively small effective population size and must be interpreted with caution (Ballard and Rand 2005). Nonetheless, our study combines a considerable amount of new chimpanzee mtDNA sequence data with the most current methods of phylogenetic reconstruction. The combination of speciation and population demographic models into a single BMCMC analysis of the chimpanzee-plus alignment yielded results that were confirmed by our more conventionally modeled bootstrapped-chimpanzee and chimpanzee-only analyses. The consistency of these three methods is striking; they all provided essentially identical tMRCA throughout the tree. This result supports the notion that this mixed-model approach, modified from Ho et al. (2008), could prove to be widely applicable to phylogenetic studies of sequences from within and between populations or species.

Our method of bootstrapping taxa may be broadly relevant as it could prove to be a useful approach for working with large data sets or otherwise computationally difficult sequence alignments. Random sampling of sequences allows an alignment of many sequences from many populations or species to be converted into a much smaller alignment that can be analyzed with a simple speciation prior. The bootstrapping step then allows each species or population to be sampled randomly and repeatedly. This eliminates the need to base inferences of entire clades on small and arbitrarily chosen subsets of sequences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mike Sanderson for the use of his computer cluster. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21 AI065371 to M.W., R01 AI58715 and R37 AI50529 to B.H.H., and Institutional Research and Career Development Award fellowship to A.B.), the Packard Foundation to M.W., and the National Science Foundation's Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship fellowship in Comparative Genomics to J.O.W.

References

- Bailey WJ, Hayasaka K, Skinner CG, Kehoe S, Sieu LC, Slightom JL, Goodman M. Reexamination of the African hominoid trichotomy with additional sequences from the primate beta-globin gene cluster. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1992;1:97–135. doi: 10.1016/1055-7903(92)90024-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JW, Rand DM. The population biology of mitochondrial DNA and its phylogenetic implications. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2005;36:621–642. [Google Scholar]

- Becquet C, Patterson N, Stone AC, Przeworski M, Reich D. Genetic structure of chimpanzee populations. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e66. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth AH. The Niger, the Volta and the Cahomey Gap as geographic barriers. Evolution. 1958;12:48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Ho SY, Phillips MJ, Rambaut A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagneux P, Gonder MK, Goldberg TL, Morin PA. Gene flow in wild chimpanzee populations: what genetic data tell us about chimpanzee movement over space and time. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:889–897. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazko GV, Nei M. Estimation of divergence times for major lineages of primate species. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:424–434. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonder MK, Disotell TR. Contrasting phylogeographic histories of chimpanzees in Nigeria and Cameroon: a multi-locus genetic analysis. In: Lehman SM, Fleagle JG, editors. Primate biogeography. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gonder MK, Disotell TR, Oates JF. New genetic evidence on the evolution of chimpanzee populations and implications for taxonomy. Int J Primatol. 2006;27:1103–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Gonder MK, Oates JF, Disotell TR, Forstner MR, Morales JC, Melnick DJ. A new west African chimpanzee subspecies? Nature. 1997;388:337. doi: 10.1038/41005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey J. The divergence of chimpanzee species and subspecies as revealed in multipopulation isolation-with-migration analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:921–933. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill WCO. The nomenclature, taxonomy and distribution of chimpanzees. In: Bourne GH, editor. The chimpanzee. New York: Karger; 1969. pp. 22–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ho SYW. Calibrating molecular estimates of substitution rates and divergence times in birds. J Avian Biol. 2007;38:409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Ho SY, Larson G, Edwards CJ, Heupink TH, Lakin KE, Holland PW, Shapiro B. Correlating Bayesian date estimates with climatic events and domestication using a bovine case study. Biol Lett. 2008;4:370–374. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobolth A, Christensen OF, Mailund T, Schierup MH. Genomic relationships and speciation times of human, chimpanzee, and gorilla inferred from a coalescent hidden Markov model. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horai S, Satta Y, Hayasaka K, Kondo R, Inoue T, Ishida T, Hayashi S, Takahata N. Man's place in Hominoidea revealed by mitochondrial DNA genealogy. J Mol Evol. 1992;35:32–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00160258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–775. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaessmann H, Wiebe V, Paabo S. Extensive nuclear DNA sequence diversity among chimpanzees. Science. 1999;286:1159–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keele BF, Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, et al. (19 co-authors) Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1. Science. 2006;313:523–526. doi: 10.1126/science.1126531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, et al. (13 co-authors) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Worobey M, Li Y, et al. (27 co-authors) Molecular ecology and natural history of simian foamy virus infection in wild-living chimpanzees. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin PA, Moore JJ, Woodruff DS. Identification of chimpanzee subspecies with DNA from hair and allele-specific probes. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1992;249:293–297. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates JF, Groves CP, Jenkins PD. The type locality of Pan troglodytes vellerosus (Gray, 1862), and implications for the nomenclature of West African chimpanzees. Primates. 2009;50:78–80. doi: 10.1007/s10329-008-0116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilbrow V. Population systematics of chimpanzees using molar morphometrics. J Hum Evol. 2006;51:646–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raaum RL, Sterner KN, Noviello CM, Stewart CB, Disotell TR. Catarrhine primate divergence dates estimated from complete mitochondrial genomes: concordance with fossil and nuclear DNA evidence. J Hum Evol. 2005;48:237–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago ML, Lukasik M, Kamenya S, et al. (23 co-authors) Foci of endemic simian immunodeficiency virus infection in wild-living eastern chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) J Virol. 2003;77:7545–7562. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7545-7562.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satta Y, Hickerson M, Watanabe H, O'Huigin C, Klein J. Ancestral population sizes and species divergence times in the primate lineage on the basis of intron and BAC end sequences. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:478–487. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro B, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. Choosing appropriate substitution models for the phylogenetic analysis of protein-coding sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:7–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiper ME, Young NM. Primate molecular divergence dates. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;41:384–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AC, Griffiths RC, Zegura SL, Hammer MF. High levels of Y-chromosome nucleotide diversity in the genus Pan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:43–48. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012364999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, Neel C, et al. (16 co-authors) Human immunodeficiency viruses: SIV infection in wild gorillas. Nature. 2006;444:164. doi: 10.1038/444164a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim JO, Sanderson MJ, Worobey M, Bjork A. Relaxed molecular clocks, the bias-variance trade-off, and the quality of phylogenetics inference. Syst Biol. 2010;59:1–8. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syp072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won Y-J, Hey J. Divergence population genetics of chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:297–307. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey M, Santiago ML, Keele BF, et al. (11 co-authors) Origin of AIDS: contaminated polio vaccine theory refuted. Nature. 2004;428:820. doi: 10.1038/428820a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N, Jensen-Seaman MI, Chemnick L, Kidd JR, Deinard AS, Ryder O, Kidd KK, Li WH. Low nucleotide diversity in chimpanzees and bonobos. Genetics. 2003;164:1511–1518. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]