Abstract

Background:

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a functional gastrointestinal disorder long considered a diagnosis of exclusion, has chronic symptoms that vary over time and overlap with those of non-IBS disorders. Traditional symptom-based criteria effectively identify IBS patients but are not easily applied in clinical practice, leaving >40% of patients to experience symptoms up to 5 years before diagnosis.

Objective:

To review the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected IBS, strengths and weaknesses of current methodologies, and newer diagnostic tools that can augment current symptom-based criteria.

Methods:

The peer-reviewed literature (PubMed) was searched for primary reports and reviews using the limiters of date (1999–2009) and English language and the search terms irritable bowel syndrome, diagnosis, gastrointestinal disease, symptom-based criteria, outcome, serology, and fecal markers. Abstracts from Digestive Disease Week 2008–2009 and reference lists of identified articles were reviewed.

Results:

A disconnect is apparent between practice guidelines and clinical practice. The American Gastroenterological Association and American College of Gastroenterology recommend diagnosing IBS in patients without alarm features of organic disease using symptom-based criteria (eg, Rome). However, physicians report confidence in a symptom-based diagnosis without further testing only up to 42% of the time; many order laboratory tests and perform sigmoidoscopies or colonoscopies despite good evidence showing no utility for this work-up in uncomplicated cases. In the absence of diagnostic criteria easily usable in a busy practice, newer diagnostic methods, such as stool-form examination, fecal inflammatory markers, and serum biomarkers, have been proposed as adjunctive tools to aid in an IBS diagnosis by increasing physicians’ confidence and changing the diagnostic paradigm to one of inclusion rather than exclusion.

Conclusion:

New adjunctive testing for IBS can augment traditional symptom-based criteria, improving the speed and safety with which a patient is diagnosed and avoiding unnecessary, sometimes invasive, testing that adds little to the diagnostic process in suspected IBS.

Keywords: diagnosis, fecal markers, serum biomarkers, stool forms, symptom-based criteria

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits.1,2 As such, IBS occurs in the absence of identifiable physical, radiologic, or laboratory indications of organic disease.2,3 Characterized as a “brain–gut disorder,”4 IBS is associated with such altered physiologic processes as changes in gut motility,5,6 visceral hypersensitivity,7 and altered immune activation of the gut mucosa and intestinal microflora.6,8

A recent systematic review of IBS epidemiologic studies noted an IBS prevalence of 3%–20% in North America, with as many as 45 million adults experiencing symptoms annually.9 In North America, IBS is more common among women than men,2,9,10 is diagnosed more often before age 50,2,9,10 and appears to be more common in lower socioeconomic populations.11,12

IBS accounts for significant health care resource utilization and economic burden. Although most symptomatic individuals do not seek medical care,13 an estimated 3.6 million annual physician visits in the United States and US $20 billion in annual direct and indirect costs are attributed to IBS symptomatology.14 Direct costs are often high in the initial diagnostic phase as historically IBS has been considered a diagnosis of exclusion, prompting sequential testing and invasive procedures in an attempt to identify organic GI disease.2,3,15 Dean et al16 found that IBS-related symptoms reduced work productivity by an estimated 21% per week (presenteeism), thus increasing costs to employers. Because IBS is not a mortal illness, the impact on patients is often underestimated. In reality, however, IBS patients have substantially poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL) than the general population and HRQoL that is on par with that seen in diabetes, depression, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.17,18 Furthermore, IBS patients have been noted to have worse body pain, lower energy or increased fatigue, and poorer social functioning than patients with dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease.18 Earlier definitive diagnosis and institution of appropriate treatment have the capacity to reduce some of these consequences of IBS symptoms.16

This article reviews the practical diagnostic evaluation of patients presenting with symptoms that may be related to IBS, the strengths and weaknesses of current diagnostic methodologies, and the newer diagnostic tools that can augment current symptom-based criteria.

Diagnosis of IBS in clinical practice

Clinical presentation

The hallmark clinical feature of IBS is abdominal pain associated with changes in bowel habits.1 Patients with symptoms consistent with constipation-predominant IBS may describe bloating, feelings that their bowel is being incompletely evacuated, and straining, whereas those with the diarrhea-predominant form typically report abdominal pain, gas, urgency, and loose stools, with more than 30% experiencing loss of bowel control.10,19,20 The typical patient is a young woman with abdominal discomfort that is relieved by passage of multiple loose liquid stools. Her symptoms will have been present for more than 3 months and may be exacerbated by factors such as fatty foods or stress. Typically, no alarm features of organic disease, such as unintentional weight loss or rectal bleeding, are present. The clinical course of IBS is chronic although symptoms are extremely variable and fluctuate over time.21 Nearly half of IBS patients report experiencing daily episodes, whereas about 75% experience at least two episodes per week.19

Challenges in IBS diagnosis

The symptoms of IBS are heterogeneous, wax and wane over time,1,13,22 and frequently overlap and/or coexist with symptoms of other common GI and non-GI disorders.22 Unfortunately, no one symptom or test is pathognomonic for IBS. Symptoms of IBS may overlap with symptoms found in other disorders, such as chronic constipation, functional dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, and lactose intolerance.22,23 IBS can coexist with other functional disorders, most notably fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, temporomandibular joint disorder, and chronic pelvic pain,24,25 and psychological conditions, such as anxiety, symptom-related fears, and somatization.4,13,24

The differential diagnosis of IBS can be broad3 and may include IBD, colorectal cancer, enteric infections, systemic hormonal disturbances, and diseases associated with malabsorption.2 Alarm features that have traditionally increased suspicion for organic disease include rectal bleeding, weight loss, iron deficiency anemia, nocturnal symptoms, and a family history of such organic diseases as colorectal cancer, IBD, and celiac disease.2,13 However, with the exception of anemia and weight loss, which have good specificity for organic disease, most alarm features have poor overall accuracy for organic pathology, including colorectal cancer.2,26

Medicolegal concerns about missing organic pathology have contributed to the practice of treating IBS as a diagnosis of exclusion,2,3,27 a common approach by many practitioners28 that leads to unnecessary testing in patients with symptoms consistent with IBS and no alarm features. Spiegel28 demonstrated that physicians who view IBS as a diagnosis of exclusion order 1.6 more diagnostic tests and spend US $364 more per patient than those who do not. However, evidence indicates that sequential testing is unlikely to uncover the underlying GI organic disease in patients without “alarm features,”2,29,30 and both the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommend using accepted symptom-based diagnostic criteria to make a positive diagnosis of IBS rather than an exhaustive diagnostic investigation.2,13,31

Despite testing, or even because of it, the diagnosis of IBS is often missed or delayed. In a survey,27 fewer than half of 35 health maintenance organization-based family practitioners could identify typical IBS symptoms27 and only 35% knew that the Manning, Rome I, and Rome II criteria are used to diagnose IBS. Other physicians report feeling comfortable diagnosing IBS at the patient’s first visit only 40% of the time.32 As a consequence of this lack of diagnostic confidence, more than 40% of patients experience IBS symptoms for at least 5 years before diagnosis is made.10,19 In addition, these patients endure unnecessary tests, procedures, or therapies and the associated financial burden that accompanies them.33 Delayed diagnosis can also increase anxiety in patients,34 more than half of whom think IBS is a “catch-all” diagnosis35 and expect numerous tests to be performed to find the “real” diagnosis.34 Common misconceptions about the diagnosis and the natural history of IBS negatively affect patients’ emotional well-being and HRQoL.35,36

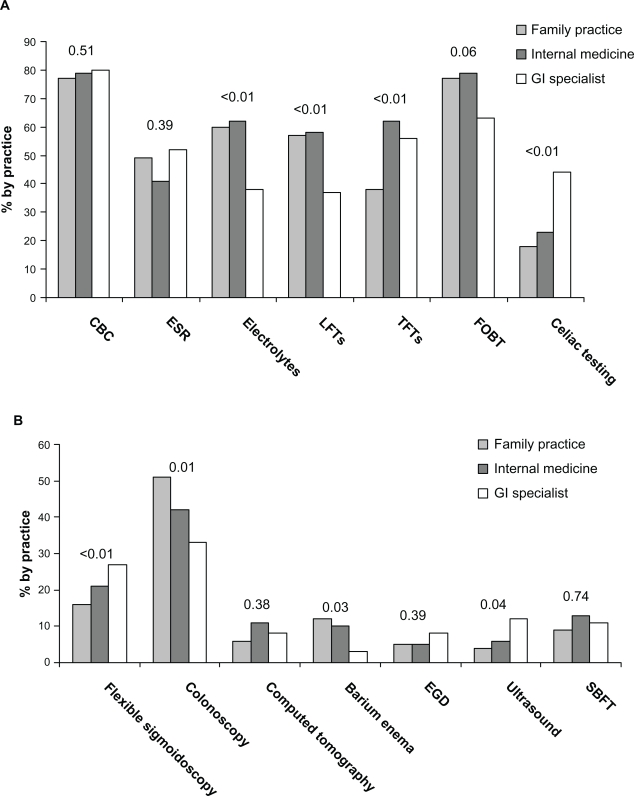

Lacy et al32 analyzed survey responses from 472 gastroenterologists, internists, and family physicians to ascertain their understanding of IBS and practice patterns. Although the physicians reported feeling capable of diagnosing IBS at the initial visit without further testing in patients without alarm features up to 42% of the time, the majority of gastroenterologists report commonly ordering laboratory tests and nearly one-third will perform flexible sigmoidoscopies or colonoscopies (Figure 1).32 All three types of physicians reported a primary goal of excluding organic disease, with symptom relief being only of secondary importance. Overall, IBS symptoms account for nearly 25% of colonoscopies in patients younger than 50 years.2,37,38

Figure 1.

Laboratory and diagnostic tests commonly ordered, presented by physician type.32 More than 1 response could be chosen. A, Laboratory tests by practice type. “Other” laboratory tests (≤2%) are not represented. B, Diagnostic tests by practice type. “Other” diagnostic tests (4%–11%) and “no studies ordered” (34%–38%) are not represented. P values are shown.

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; CBC, complete blood count; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LFT, liver function test; TFT, thyroid function test; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; SBFT, small bowel follow-through.

Current state of IBS diagnostics

Symptom-based criteria

Several sets of criteria have been developed to identify and standardize the diagnosis of IBS (Table 1).2,3 The early Manning criteria39 identified six symptoms that increase the likelihood of an IBS diagnosis but do not stipulate a required number or duration of symptoms. In 1984, Kruis et al40 developed a system of symptoms, physical findings, and laboratory results, and in 1990, an international working group41 developed Rome I criteria in an attempt to reduce unnecessary testing and provide a uniform framework for selecting patients for diagnostic and therapeutic trials in IBS.3,31 These criteria were revised in 1999 by the Rome II working group and again in 2006 by the Rome III working group (Table 1).1,42 Unfortunately, such criteria can be difficult to apply in busy practices, and despite extensive use in research settings, the Rome II and III criteria are not sufficiently validated.2,3,31 Indeed, only one study evaluated the accuracy of the Rome I criteria for diagnosing IBS.43

Table 1.

Comparison of symptom-based criteria

| Criteria/y | Symptoms, signs, and laboratory investigations included in criteria | Symptom duration required | Diagnostic performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manning et al39 1978 | Abdominal pain relieved by defecation; more frequent stools with onset of pain; looser stools with onset of pain; passage of mucus per rectum; feeling of incomplete emptying; patient-reported visible abdominal distension | None | Sensitivity 78%, specificity 72%, positive LR 2.9 (95% CI, 1.3–6.4)31 |

| Kruis et al40 1984 | Symptoms (reported by patient using a form): abdominal pain, flatulence, or bowel irregularity; description of abdominal pain as burning, cutting, very strong, terrible, feeling of pressure, dull, boring, or “not so bad” | >2 yr | Sensitivity 77%, specificity 89%, positive LR 8.6 (95% CI, 2.9–26.0)31 |

| Signs (determined by physician): abnormal physical findings and/or history; pathognomonic for any diagnosis other than IBS; ESR >20 mm/2 h; leukocytosis >10,000 cells/μL; anemia (hemoglobin <12 g/dL for women, <14 g/dL for men); physician impression is that patient’s history suggests blood in the stools | |||

| Rome I criteria41 1990 | Abdominal pain or discomfort relieved with defecation or associated with a change in stool frequency or consistency; any variation in defecation on ≥25% of occasions evidenced by 3 of the following:

|

≥3 mo | Sensitivity 65%, specificity 100%, PPV 100%43 |

| Rome II criteria13,42 1999 | Abdominal discomfort or pain that has 2 of 3 features:

|

≥12 wk (need not be consecutive in past year) | Not validated |

| Rome III criteria1 2006 | Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort ≥3 d/mo in the past 3 mo associated with ≥2 of the following:

|

Symptom onset: ≥6 mo before diagnosis | Not validated |

Adapted with permission from Ford AC, Talley NJ, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Vakil NB, Simel DL, Moayyedi P. Will the history and physical examination help establish that irritable bowel syndrome is causing this patient’s lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms? JAMA. 2008;300(15):1793–1805.31 Copyright © 2008 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Abbreviations: Cl, confidence interval; LR, logistic regression; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; PPV, positive predictive value.

The utility of symptom-based criteria in primary care settings has been brought into question.31,44 As such, alternative IBS diagnostic criteria have been sought. In one such instance, 10 European family practitioners developed a structured consensus process to define IBS diagnostic criteria. In their process, the key features identified for IBS diagnostic purposes differed substantially from those stipulated by Rome III.44

Traditional diagnostic tests for IBS

The traditional diagnostic work-up of IBS includes common tests that may be helpful in differentiating IBS with alarm features of organic disease although they are not recommended in patients with typical IBS symptoms who do not have alarm features.2,13,43 The choice of test is usually guided by the nature and severity of symptoms and the patient’s expectations and concerns.2 Advantages and disadvantages of these traditional tests are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of traditional diagnostic methods

| Tests | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| CBC, TSH, serum chemistries, FOBT | Inexpensive | Limited value in identifying organic disease in patients without alarm features2 |

| Stool for ova and parasites | Noninvasive, inexpensive May be useful in patients with clinical features, symptom pattern, and geographic area suggestive of infection13 |

Limited value in identifying organic disease in patients without alarm features2 |

| Hydrogen breath tests | May be useful when lactose maldigestion is suspected51,56 Noninvasive |

Need for specialized equipment, dedicated space, and technical support51 False-positive results possible in smokers and those with poor oral hygiene51 Limited value in identifying organic disease in patients without alarm features2 |

| Celiac serologies (anti-tTG, EMA, AGA) | Routine use in IBS-D and IBS-M patients helpful in identifying celiac disease2,58 | – |

| Abdominal imaging | May be useful in excluding mechanical obstruction in patients with IBS-C and alarm features2 | Expensive Low diagnostic yield in patients without alarm features29 |

| Endoscopy/colonoscopy | Useful for identifying organic diseases (particularly IBD, colorectal cancer, and microscopic colitis) in patients with IBS-D and alarm features2 Can exclude mechanical obstruction in patients with IBS-C and alarm features2 Upper endoscopy with biopsies may be useful in detecting celiac disease or SIBO2 |

Expensive Low diagnostic yield in patients without alarm features3,49 Normal findings not associated with improved HRQoL37 |

Abbreviations: CBC, complete blood count; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; anti-tTG, antibodies to tissue transglutaminase; EMA, endomysial antibodies; AGA, antigliadin antibodies; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-D, diarrhea-predominant IBS; IBS-M, mixed IBS; IBS-C, constipation-predominant IBS; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SIBO, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth; HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

Newer diagnostic tools, such as the examination of stool forms, fecal inflammatory markers, and the use of serum biomarker, may be useful adjuncts to traditional evaluations of patients with suspected IBS. These simple tests may allow clinicians to distinguish IBS from non-IBS disorders in a cost-effective manner,45,46 possibly facilitating a paradigm shift from approaching IBS as a diagnosis of exclusion to one of inclusion.45 Pimentel et al45 have advocated use of specific clinical questions regarding bowel form and function that may help distinguish between IBS and non-IBS diarrheal disease with a high sensitivity. Already used routinely in some European countries,47 fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin are highly sensitive and specific for intestinal inflammation and can differentiate IBD from IBS.23,48 Recently, an IBS diagnostic panel composed of 10 serum biomarkers that are linked to multiple regulatory pathways and proteins associated with IBS has been developed. Using a smart diagnostic algorithm to interpret the data obtained, this panel may be especially helpful in the early stages of the diagnostic process in confirming suspected IBS.33

Routine blood and stool hemoccult tests

The AGA recommends a screening of complete blood count and stool hemoccult for patients presenting with IBS symptoms of short duration, family history of colorectal cancer or IBD, older age at symptom onset, or lack of concurrent psychosocial difficulties.13 However, these tests offer little value in identifying organic disease in patients with typical IBS symptoms but no alarm features. In a study of 196 patients with suspected IBS, serum chemistries and complete blood counts failed to uncover the underlying organic disease in any patient.49 Similarly, a review of data from five studies in 2,160 IBS patients showed comparable prevalence rates of abnormal thyroid function test results between the study patients (4.2%) and the general population (5%–9%).2 Further, a causal relationship between the thyroid dysfunction and IBS symptoms was not established.2

Stool examinations for ova and parasites

Stool examinations may be useful if the patients’ symptom pattern, geographic area, and clinical features (eg, diarrhea in an area of known endemic infection) suggest an infectious etiology.13 However, such tests are not recommended for routine use in patients without alarm features or infection,2,13 as findings are significant in fewer than 2% of patients with IBS.2,49,50

Carbohydrate breath test

The carbohydrate breath test has been used by gastroenterologists for many years to detect lactose malabsorption. The test measures exhaled levels of hydrogen and/or methane produced during the metabolism of carbohydrate substrates by intestinal bacteria.51 Breath testing for lactose intolerance may be useful in patients with typical IBS symptoms and suspected lactose maldigestion. It is important, however, to establish that dietary intake of lactose is >240 mL of milk (or equivalent) per day before testing for lactose intolerance, as Suarez et al52 have shown that patients with documented lactose malabsorption are able to tolerate 240 mL of milk per day with minimal or no symptoms. A systematic review of data from seven studies involving 2,149 IBS patients demonstrated a 35% prevalence of lactose maldigestion (95% confidence interval [CI]: 17–56) by lactose breath testing,2 whereas a separate analysis of three case-control studies involving 425 patients (251 of whom had IBS) revealed a prevalence of 38% in IBS patients vs 26% in controls (odds ratio [OR] = 2.57; 95% CI: 1.27–5.22).2 Despite the frequent occurrence of lactose intolerance in patients with IBS, no causal relationship has been established between lactose intolerance and IBS symptoms. However, given the possibility that IBS patients are more sensitive to the clinical consequences of lactose maldigestion,53 the ACG IBS Task Force has recommended considering a lactose hydrogen breath test in patients whose history and food diary review suggest potential lactose maldigestion.2

Recently, carbohydrate breath test has been used in an attempt to identify patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).51 Emerging evidence suggests that SIBO plays a pathogenic role in IBS,54,55 although this remains contentious. The use of carbohydrate breath test to diagnose SIBO in IBS patients has yielded conflicting results. In a systematic review by the ACG IBS Task Force, the prevalence of a positive lactulose breath test was 65% (95% CI: 47–81) in 432 IBS patients from three studies, whereas the prevalence of a positive glucose breath test was 36% (95% CI: 29–43) in 208 patients from two studies.2 Because lactulose is not absorbed by the intestine, lactulose breath tests should detect bacteria anywhere along the gut.51,56 Because glucose is absorbed rapidly, glucose breath testing can detect bacteria only in the duodenum and proximal jejunum, demonstrating lower sensitivity than lactulose breath testing.51,56 Posserud et al57 used jejunal aspirate culture to assess the prevalence of SIBO in 162 patients with IBS and found a prevalence of SIBO (defined as ≥105 colony-forming units [CFU]/mL) of 4% in patients with IBS (7 of 162) and in controls (1 of 26). Glucose hydrogen breath testing performed on 54 IBS patients and 20 controls with <105 CFU/mL was positive in only one IBS patient; lactulose hydrogen breath testing in 46 IBS patients and 21 controls with <105 CFU/mL yielded positive results in 15% (7 of 46) of IBS patients and 20% (4 of 21) of controls.57 The ACG IBS Task Force does not recommend breath testing for SIBO in patients with IBS.2

Celiac testing

The prevalence of serologic evidence of celiac disease among IBS patients (endomysial antibodies [EMA] or tissue transglutaminase antibodies [anti-tTG]) is more than three fold higher than among controls without IBS, and the prevalence of biopsy-proven celiac disease is four fold higher than among controls.58 Routine serologic screening for celiac disease is recommended for patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) or mixed features of IBS (IBS-M).2 EMA and anti-tTG have a higher positive predictive value for celiac disease than the immunoglobulin (Ig) A-class antigliadin antibodies.58

Imaging

Neither abdominal nor colonic imaging tests are likely to reveal the structural abnormalities that explain symptoms of IBS in patients with no alarm features.2,29 In a study of 125 patients with suspected IBS on the basis of the Rome I criteria, abdominal ultrasound failed to reveal any serious intra-abdominal pathology.29 Although abnormalities were detected in 18% of patients, findings did not change a diagnosis.29 In three studies, in a total of 636 IBS patients, imaging with barium enema or colonoscopy revealed organic or structural disease in 1.3% of patients, which does not exceed the prevalence in the general population.2

Endoscopy or colonoscopy

Studies evaluating endoscopic investigation for suspected IBS do not support their routine use in patients without alarm features. Hamm et al50 assessed the value of such tests as flexible sigmoidoscopies, barium enemas, and colonoscopies in 1,452 patients meeting Rome criteria for at least 6 months. Among the 306 patients undergoing colonic examination, abnormalities were detected in seven patients (2%): IBD in three, colonic obstruction in one, and colonic polyps without malignancy in three.50 In a smaller study of 196 patients with IBS, 43 colonic structural abnormalities were found in 34 patients. Nine (26%) of these patients had indicators suggestive of organic disease49 and, of these, only two (1%) had abnormalities (one colitis, one colon cancer) that may have caused IBS symptoms.3,49 MacIntosh et al59 performed flexible sigmoidoscopy with rectal biopsy in 89 patients with IBS, most of whom met Rome I criteria. None of the findings suggested alternative diagnoses that could account for the GI symptoms in any patient. Investigators concluded that such studies are costly and unnecessary in IBS.3,59 A retrospective review37 of data from 458 patients found that colonoscopy had a low diagnostic yield and normal findings were not associated with higher HRQoL owing to diagnostic reassurance.

Based on these and other findings, patients younger than 50 years with IBS symptoms but no alarm features do not require routine colonic imaging. However, patients aged > 50 years (45 years in African Americans) should follow expert recommendations for colonic imaging for colorectal cancer screening2,38,60 and those aged > 50 years with alarm features should undergo colonoscopy to rule out organic disease.2

Patients with IBS-D and alarm features should be examined specifically for colorectal cancer and IBD and potentially undergo random mucosal biopsies to rule out microscopic colitis, which has a prevalence of 2.3% among patients with IBS-D.2,61 The prevalence of microscopic colitis is highly age-dependent as shown in a Swedish epidemiology study of 1,018 patients presenting with nonbloody diarrhea who underwent colonoscopy; 10% overall, but 20% of those >70 years, received a diagnosis of microscopic colitis.62 Patients with IBS-C should be evaluated for mechanical obstruction, which can be done by colonoscopy, virtual colonography, or barium enema.2 Upper endoscopy with small bowel biopsies can be considered to test for celiac disease or SIBO in patients with laboratory or stool findings suggestive of malabsorption.2

Newer, innovative tests for IBS

Several noninvasive diagnostic approaches were investigated for their ability to discriminate IBS from non-IBS disorders. Although more data are needed,45,48 these tests show potential as adjuncts to traditional diagnostic methods in IBS33,63 and may reduce unnecessary testing in clinical practice.33,45,46

Examination of stool forms

Pimentel et al45 evaluated the variations in frequency and consistency of bowel habits over time to distinguish diarrhea secondary to IBS from diarrhea associated with active celiac disease, ulcerative colitis (UC), and Crohn’s disease. The basis for this testing is that patients with IBS-D, whose bowel function varies with changes in neuromuscular function, will more likely experience irregular bowel function and stool form than those with non-IBS causes of diarrhea. Sixty-two IBS-D patients and 37 non-IBS patients (UC, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease) completed a questionnaire on their bowel habits and stool forms during the preceding week. More IBS than non-IBS patients reported daily variations in stool form and frequency of bowel habits (79% vs 35%; P < 0.00001).45 Further, 81% of IBS patients and 41% of those without IBS reported having at least three stool forms per week; the difference of three stool forms per week has a sensitivity of 68% and specificity of 84% in differentiating IBS.45 The success of this simple tool in distinguishing between IBS and non-IBS diarrheal disease may help avoid unnecessary diagnostic testing.45

Fecal markers

Increasing evidence supports the utility of fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin in differentiating between IBD and IBS because these markers can identify active intestinal inflammation in IBD.23,48,63–65 Easily measured in feces, calprotectin and lactoferrin are stable, neutrophil-derived proteins that increase in concentration in response to leukocyte migration into the gut.48,64,66

Tibble et al46 examined the diagnostic efficacy of fecal calprotectin in 602 patients referred to a gastroenterology clinic. With a cutoff value of 10 mg/L, calprotectin had an 89% sensitivity and a 79% specificity for organic disease (ie, IBD) with an OR of 27.8 (95% CI: 17.6–43.7; P < 0.0001). Other investigators demonstrated similar diagnostic utility of these fecal markers to differentiate active IBD from inactive disease and from IBS.64,65 Schoepfer et al23 prospectively found fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin levels in patients with IBD to be over the levels in patients with IBS and in healthy controls, but did not differ between IBS patients and healthy controls. Although the elevated levels of fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin are potentially valuable when screening for intestinal inflammation and discriminating between organic and functional diseases,46,48 neither the cause of the inflammatory process leading to the elevations can be discerned with these markers nor are the elevations able to “rule in” a diagnosis of IBS, given that differences between IBS and healthy controls are not significant.

Serologic markers

A number of altered physiological pathways have been identified in patients with IBS. The major pathogenic processes include altered gut motility and visceral hypersensitivity, which are believed to be due to the dysregulation of brain–gut axis pathways,67 immune dysregulation in the GI tract,68 altered gut flora,2,54,56,69 and complex interactions between neuronal and hormonal factors.33 These alterations have prompted investigations of IBS biomarkers that may help elucidate the pathophysiology of the disorder68 and aid in the diagnosis of the disease.33

Lembo et al33 described a panel of 10 serum biomarkers that may be useful to help differentiate IBS from non-IBS disease and healthy controls. This biomarker panel was derived from a literature review, which identified >60,000 possible biomarkers common to IBS and other GI diseases (both functional and organic) and part of the differential diagnosis in suspected IBS. Subsequently, this group of biomarkers was further refined to 140 biomarkers by identifying those that were common across multiple pathways, those that were serum based, and those for which assays were commercially available. Assays of these 140 biomarkers in IBS and control samples resulted in significant median differences in 16 biomarkers. Expression values of these 16 biomarkers were then evaluated in >300,000 algorithms, ultimately identifying 10 biomarkers, the combined performance of which provided the greatest accuracy in distinguishing IBS patients from non-IBS patients. The panel includes interleukin-1β, growth-related oncogene-α, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, antihuman anti-tTG, tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, antibody to bacterial flagellin (anti-CBir1), anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA-IgA), and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA).33 Six of these biomarkers have been associated with metabolic dysregulation in IBS, whereas others (ASCA, ANCA, and anti-CBir1) have typically been associated with IBD. Notably, one study demonstrated elevated levels of anti-CBir1 in a subset of patients with postinfectious IBS, presumably the result of bacterial infection and immune system activation.70 The role of inflammatory processes in IBS and concomitant changes in biomarker expression need to be more fully evaluated, especially as they relate to potential changes over the course of the disease. Likewise, anti-tTG is a serum antibody known to be highly specific for only celiac disease.

After the biomarkers were identified, a predictive modeling tool was used to discern patterns of serum concentrations that best differentiated IBS patients from those with non-IBS GI disease (IBD, non-IBS functional GI disorders, and celiac disease) and healthy controls in a training cohort of 1,205 patients.33 This model was then validated in a different cohort of 516 patients with IBS or a non-IBS GI disease and healthy controls. The overall diagnostic accuracy of this test in differentiating IBS from non-IBS was 70% (sensitivity 50%, specificity 88%), and at a 50% IBS prevalence, the positive predictive value was 81% and the negative predictive value was 64%, leading investigators to conclude that a positive test result can help confirm a suspicion of IBS although the sensitivity is insufficient for a negative test to reliably exclude the diagnosis.33 Although not appropriate for use as a single diagnostic tool, this biomarker panel may be a cost-effective adjunct to traditional diagnostic methods in an overall work-up of IBS.33 A systematic review and a meta-analysis examining various diagnostic criteria in IBS have reported that the Manning, Kruis, and Rome I criteria have similar positive and negative likelihood ratios of predicting an IBS diagnosis in comparison to the 10-biomarker diagnostic panel.31,71 As the only serologic test that “rules in” IBS, the panel may provide optimal utility early in the disease course, avoiding more expensive and invasive testing, introducing greater confidence in a “correct” diagnosis, and allowing earlier initiation of an appropriate treatment plan. As the biomarker test evolves through scientific and technologic advances, sensitivity and specificity should improve33 and lead to better clinical trials and quality of life for patients with IBS.

Conclusion

The substantial human and economic cost associated with IBS necessitates development of efficient diagnostic and management strategies.37 Although among the most common disorders in gastroenterology and primary care practices, IBS continues as a substantial diagnostic challenge. A lack of confidence in symptom-based diagnosis, a broad differential diagnosis, patient misconceptions and expectations, and medicolegal concerns about missing organic disease may all contribute to unnecessary and costly diagnostic testing.2,27,34 Nevertheless, the diagnosis of IBS is often missed or delayed. Innovative diagnostic tests, such as examination of stool forms, fecal markers of inflammation, and IBS serology, offer promise as noninvasive, cost-efficient adjuncts to traditional diagnostic methods, particularly early in the disorder.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank John Simmons, MD, for his assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Writing support was provided with funding from Prometheus Laboratories, Inc.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr Burbige has served as a speaker and consultant for Prometheus Laboratories and as a speaker for Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(Suppl 1):S1–S35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cash BD, Chey WD. Irritable bowel syndrome – an evidence-based approach to diagnosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(12):1235–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer EA. Clinical practice. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(16):1692–1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0801447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serra J, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Impaired transit and tolerance of intestinal gas in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2001;48(1):14–19. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camilleri M. Evolving concepts of the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome: to treat the brain or the gut? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(Suppl 2):S46–S48. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181a1174b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozu T, Kudaira M, Kitamori S, Uehara A. Repetitive rectal painful distention induces rectal hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(3):217–222. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1748-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiller RC, Jenkins D, Thornley JP, et al. Increased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability following acute Campylobacter enteritis and in post-dysenteric irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2000;47(6):804–811. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.6.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito YA, Schoenfeld P, Locke GR., III The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(8):1910–1915. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hungin AP, Chang L, Locke GR, Dennis EH, Barghout V. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(11):1365–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews EB, Eaton SC, Hollis KA, et al. Prevalence and demographics of irritable bowel syndrome: results from a large Web-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(10):935–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minocha A, Johnson WD, Abell TL, Wigington WC. Prevalence, sociodemography, and quality of life of older versus younger patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(3):446–453. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(6):2108–2131. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Gastroenterological Association . The Burden of Gastrointestinal Diseases. Bethesda, MD: American Gastroenterological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longstreth GF, Yao JF. Irritable bowel syndrome and surgery: a multivariable analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(7):1665–1673. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dean BB, Aguilar D, Barghout V, et al. Impairment in work productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with IBS. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(1 Suppl):S17–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Serag HB, Olden K, Bjorkman D. Health-related quality of life among persons with irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(6):1171–1185. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(3):654–660. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.16484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders IBS in the Real World Survey. Summary findings. International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Available from: http://about-constipation.org/pdfs/IBSRealWorld.pdf. Accessed Aug 19, 2010.

- 20.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse Irritable bowel syndrome. Available from: http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/ibs/index.htm. Accessed Aug 19, 2010.

- 21.Camilleri M, Choi MG. Review article: irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(1):3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.84256000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frissora CL, Koch KL. Symptom overlap and comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other conditions. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7(4):264–271. doi: 10.1007/s11894-005-0018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoepfer AM, Trummler M, Seeholzer P, Seibold-Schmid B, Seibold F. Discriminating IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes, CRP, and IBD antibodies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(1):32–39. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aaron LA, Burke MM, Buchwald D. Overlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(2):221–227. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford AC, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Rodgers CC, Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. Diagnostic utility of alarm features for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2008;57(11):1545–1553. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.159723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longstreth GF, Burchette RJ. Family practitioners’ attitudes and knowledge about irritable bowel syndrome: effect of a trial of physician education. Fam Pract. 2003;20(6):670–674. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel BM. Do physicians follow evidence-based guidelines in the diagnostic work-up of IBS? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4(6):296–297. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francis CY, Duffy JN, Whorwell PJ, Martin DF. Does routine abdominal ultrasound enhance diagnostic accuracy in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(7):1348–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cash BD, Schoenfeld P, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(11):2812–2819. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ford AC, Talley NJ, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Vakil NB, Simel DL, Moayyedi P. Will the history and physical examination help establish that irritable bowel syndrome is causing this patient’s lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms? JAMA. 2008;300(15):1793–1805. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacy BE, Rosemore J, Robertson D, Corbin DA, Grau M, Crowell MD. Physicians’ attitudes and practices in the evaluation and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(8):892–902. doi: 10.1080/00365520600554451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lembo AJ, Neri B, Tolley J, Barken D, Carroll S, Pan H. Use of serum biomarkers in a diagnostic test for irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(8):834–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casiday RE, Hungin AP, Cornford CS, de Wit NJ, Blell MT. Patients’ explanatory models for irritable bowel syndrome: symptoms and treatment more important than explaining aetiology. Fam Pract. 2009;26(1):40–47. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halpert A, Dalton CB, Palsson O, et al. What patients know about irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and what they would like to know. National Survey on Patient Educational Needs in IBS and development and validation of the Patient Educational Needs Questionnaire (PEQ) Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(9):1972–1982. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lacy BE, Weiser K, Noddin L, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: patients’ attitudes, concerns and level of knowledge. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(11):1329–1341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spiegel BM, Gralnek IM, Bolus R, et al. Is a negative colonoscopy associated with reassurance or improved health-related quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(6):892–899. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lieberman DA, Holub J, Eisen G, Kraemer D, Morris CD. Utilization of colonoscopy in the United States: results from a national consortium. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(6):875–883. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manning AP, Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Morris AF. Towards positive diagnosis of the irritable bowel. Br Med J. 1978;2(6138):653–654. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6138.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kruis W, Thieme C, Weinzierl M, Schussler P, Holl J, Paulus W. A diagnostic score for the irritable bowel syndrome. Its value in the exclusion of organic disease. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drossman DA, Thompson WG, Talley NJ. Identification of sub-groups of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology International. 1990;3(4):159–172. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drossman DA. Review article: an integrated approach to the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(Suppl 2):3–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.0130s2003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vanner SJ, Depew WT, Paterson WG, et al. Predictive value of the Rome criteria for diagnosing the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(10):2912–2917. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubin G, De WN, Meineche-Schmidt V, Seifert B, Hall N, Hungin P. The diagnosis of IBS in primary care: consensus development using nominal group technique. Fam Pract. 2006;23(6):687–692. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pimentel M, Hwang L, Melmed GY, et al. New clinical method for distinguishing D-IBS from other gastrointestinal conditions causing diarrhea: the LA/IBS diagnostic strategy. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(1):145–149. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0694-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Foster R, Forgacs I, Bjarnason I. Use of surrogate markers of inflammation and Rome criteria to distinguish organic from nonorganic intestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(2):450–460. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poullis A, Foster R, Mendall MA, Fagerhol MK. Emerging role of calprotectin in gastroenterology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18(7):756–762. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kane SV, Sandborn WJ, Rufo PA, et al. Fecal lactoferrin is a sensitive and specific marker in identifying intestinal inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(6):1309–1314. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tolliver BA, Herrera JL, DiPalma JA. Evaluation of patients who meet clinical criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(2):176–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamm LR, Sorrells SC, Harding JP, et al. Additional investigations fail to alter the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in subjects fulfilling the Rome criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(5):1279–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saad RJ, Chey WD. Breath tests for gastrointestinal disease: the real deal or just a lot of hot air? Gastroenterology. 2007;133(6):1763–1766. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suarez FL, Savaiano DA, Levitt MD. A comparison of symptoms after the consumption of milk or lactose-hydrolyzed milk by people with self-reported severe lactose intolerance. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(1):1–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di Stefano M, Miceli E, Mazzocchi S, Tana P, Moroni F, Corazza GR. Visceral hypersensitivity and intolerance symptoms in lactose malabsorption. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(11):887–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pimentel M, Park S, Mirocha J, Kane SV, Kong Y. The effect of a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(8):557–563. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-8-200610170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(12):3503–3506. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin HC. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a framework for understanding irritable bowel syndrome. JAMA. 2004;292(7):852–858. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Posserud I, Stotzer PO, Bjornsson ES, Abrahamsson H, Simren M. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2007;56(6):802–808. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.108712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ford AC, Chey WD, Talley NJ, Malhotra A, Spiegel BM, Moayyedi P. Yield of diagnostic tests for celiac disease in individuals with symptoms suggestive of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):651–658. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacIntosh DG, Thompson WG, Patel DG, Barr R, Guindi M. Is rectal biopsy necessary in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(10):1407–1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pignone M, Rich M, Teutsch SM, Berg AO, Lohr KN. Screening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(2):132–141. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nojkov B, Rubenstein JH, Cash BD, et al. The yield of colonoscopy in patients with non-constipated irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): results from a prospective, controlled US trial [abstract 178] Gastroenterology. 2008;134(Suppl 1(60)):A30. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olesen M, Eriksson S, Bohr J, Jarnerot G, Tysk C. Microscopic colitis: a common diarrhoeal disease. An epidemiological study in Orebro, Sweden, 1993–1998. Gut. 2004;53(3):346–350. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.014431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tibble J, Teahon K, Thjodleifsson B, et al. A simple method for assessing intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2000;47(4):506–513. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.4.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Langhorst J, Elsenbruch S, Koelzer J, Rueffer A, Michalsen A, Dobos GJ. Noninvasive markers in the assessment of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases: performance of fecal lactoferrin, calprotectin, and PMN-elastase, CRP, and clinical indices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(1):162–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Silberer H, Kuppers B, Mickisch O, et al. Fecal leukocyte proteins in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Lab. 2005;51(3–4):117–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guerrant RL, Araujo V, Soares E, et al. Measurement of fecal lactoferrin as a marker of fecal leukocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(5):1238–1242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1238-1242.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.American Gastroenterological Association American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(6):2105–2107. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aerssens J, Camilleri M, Talloen W, et al. Alterations in mucosal immunity identified in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(2):194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kassinen A, Krogius-Kurikka L, Makivuokko H, et al. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(1):24–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schoepfer AM, Schaffer T, Seibold-Schmid B, Muller S, Seibold F. Antibodies to flagellin indicate reactivity to bacterial antigens in IBS patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:1110–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ford AC. 10-biomarker algorithm to identify irritable bowel syndrome: author’s reply. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(1):95–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]