Abstract

Manganese(II) chloride reacts with trimethylsilyl triflate (TMS(OTf) where OTf = -OSO2CF3) in a 1:1 mixture of acetonitrile and tetrahydrofuran, and after recrystallization affords the linear coordination polymer [MnII(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n. Each distorted octahedral manganese(II) center in the polymeric chain has trans-acetonitriles and the remaining equatorial coordination positions are occupied by the bridging triflate anions. Dissolving [MnII(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n in equal volumes of acetonitrile and pyridine followed by recrystallization with diethyl ether yields trans-[MnII(C5H5N)4(OTf)2]. The distorted octahedral geometry of the manganese center features monodentate trans-triflate anions and four equatorial pyridines. Exposure of either [MnII(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n or [MnII(C5H5N)4(OTf)2] to water readily gives [MnII(H2O)6](OTf)2. XRD reveals hydrogen-bonding interactions between the [MnII(H2O)6]2+ cation and the triflate anion. All three of these species are easily crystallized and provide convenient sources of manganese(II) for further synthetic elaboration.

Keywords: Manganese(II) compounds, triflate, crystal structure, coordination polymer

In recent years, the metal salts of weakly coordinating anions have been used to great effect in the preparation of coordination complexes.[1, 2] The thermal stability, high lability, and chemical inertness to most conditions of trifluoromethane sulfonate anions (or triflate, CF3SO3- = OTf) has led to their wide use in inorganic chemistry; particularly in catalytic applications.[1-3] Metal triflates have been touted as a means to avoid the explosive hazards associated with metal perchlorates,[4, 5] and a wide variety of transition metal triflates have now been reported.[3] In spite of several detailed reports, the acetonitrile complex of manganese(II) triflate has been reported with a variety of constitutions: [Mn(CH3CN)4](OTf)2,[6] Mn(OTf)2·2CH3CN,[7] Mn(OTf)2·1CH3CN,[8] and Mn(OTf)2.[3, 9, 10] In each of these preparations of manganese triflate complexes, the characterization data provided are insufficient to ascertain the exact constitution. Furthermore, the most frequently cited reference for the preparation of Mn(OTf)2·1CH3CN admits to inconsistent combustion analyses,[8] and most preparations do not report the characteristic triflate vibrational modes.[11] In this communication, we report easily reproducible methods for the preparation[12] and crystallization[13] of three manganese(II) triflate complexes of known constitution.

Manganese(II) chloride reacts rapidly with trimethylsilyl triflate with loss of trimethylsilyl chloride to afford a colorless solution. A slight excess of TMS(OTf) ensures anhydrous reaction conditions and this reagent has been employed previously for the generation of metal triflates.[14-16] Recrystallization from a concentrated acetonitrile solution with diethyl ether over one day yields colorless crystals of [Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n (1) in high yield. The crystallinity is lost when dried under vacuum for an extended period of time affording a white powder. The vibrational features of the powder are identical to those of the crystalline solid.

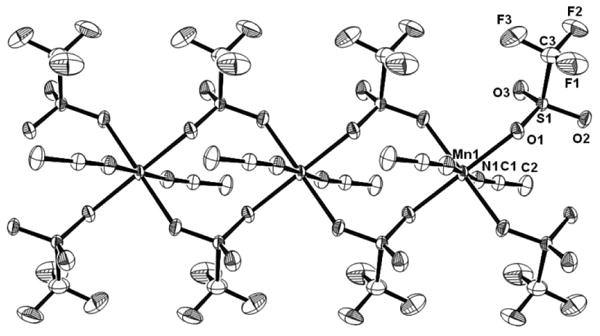

The structure of the acetonitrile complex 1 determined by X-ray diffraction (Figure 1, Table 1), shows that the manganese center in this coordination polymer exhibits a distorted octahedral geometry. The manganese atom lies on an inversion center and only one of the triflates and one of the acetonitrile ligands are crystallographically distinct. The bridging triflate anion brings the two manganese centers of the polymer to a distance of 5.1333 Å. The two distinct Mn-O bond distances show only slight variation (2.1673(8) and 2.1755(7) Å) and are comparable to those observed in other high-spin manganese(II) triflate complexes.[17-28] The axial Mn-N bond distances of 2.2076(9) Å are similar to values one might expect for nitrile coordinated high-spin manganese(II) centers.[29-32] The Mn1-N1-C1 bond angle (153.68(9)°) exhibits significant distortion as observed in Fe(CH3CN)4(OTf)2 (158.8°).[33] We observe no hydrogen-bonding interactions between the bound acetonitrile and triflate. The distortion of the Mn-NCCH3 bond angle may be due to the tight packing of the linear coordination polymer chains which are only 2.774 Å apart (refer to Supplementary Material Figure S1 for a packing diagram illustrating the ‘inter-chain’ F⋯F distance). This distance is only slightly longer than the sum of the van der Waals radii of the associated F atoms (2.70 Å).

Figure 1.

ORTEP plot of several complete coordination spheres of the coordination polymer [Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n showing 50% probability thermal ellipsoids and the labeling scheme for unique atoms. All hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Table 1. Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (°) for [Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n, trans-[Mn(C5H5N)4(Otf)2], and [Mn(H2O)6](Otf)2.

| [Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n | [Mn(C5H5N)4(OTf)2] | [Mn(H2O)6](OTf)2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn-O(1) | 2.1755(7) | Mn-O1 | 2.1577(13) | Mn-O(1W) | 2.1624(10) |

| Mn-O(1)#3a | 2.1755(7) | Mn-O4 | 2.1583(13) | Mn-O(1W)#4 | 2.1625(10) |

| Mn-O(2)#1 | 2.1673(8) | Mn-N1 | 2.2725(16) | Mn-O(1W)#5 | 2.1625(10) |

| Mn-O(2)#2 | 2.1673(8) | Mn-N2 | 2.2546(15) | Mn-O(1W)#6 | 2.1625(10) |

| Mn-N(1) | 2.2079(9) | Mn-N3 | 2.2909(15) | Mn-O(2W) | 2.1474(14) |

| Mn-N(1)#3 | 2.2079(9) | Mn-N4 | 2.2533(14) | Mn-O(2W)#4 | 2.1474(14) |

| O(2)#1-Mn-O(2)#2 | 180.00(4) | O1-Mn-O4 | 173.13(6) | O(2W)-Mn-O(2W)#4 | 180.0 |

| O(1)-Mn-O(2)#2 | 90.45(3) | O1-Mn-N1 | 90.07(6) | O(1W)-Mn-O(2W) | 91.73(4) |

| O(1)-Mn-O(2)#1 | 89.55(3) | O4-Mn-N1 | 94.78(6) | O(1W)-Mn-O(2W)#4 | 88.27(4) |

| O(2)#1-Mn-N(1)#3 | 91.13(3) | N1-Mn-N2 | 90.13(5) | O(1W)-Mn-O(1W)#5 | 86.19(7) |

| N(1)-Mn-N(1)#3 | 180.0 | N1-Mn-N3 | 178.81(6) | O(1W)#3-Mn-O(1W)#5 | 93.81(7) |

| O(1)-Mn-O(1)#3 | 180.0 | N1-Mn-N4 | 89.40(5) | O(1W)-Mn-O(1W)#1 | 180.0 |

| C(1)-N(1)-Mn | 153.68(9) | N2-Mn-N4 | 179.53(6) | O(1W)#4-Mn-O(1W)#6 | 180.00(9) |

Symmetry transformations used to generate equivalent atoms: #1 x+1,y,z; #2 -x-1,-y,-z-1; #3 -x,-y,-z-1; #4 -x,-y,-z #5 -x,y,-z #6 x,-y,z.

Interestingly, a KBr pellet of crystals of 1 displays IR-active vibrational features at 2310, 2281, 1312, 1188 and 1039 cm-1 (Figure S2.A and Table S1). These bands are comparable to those reported for the previously reported [Mn(CH3CN)4](OTf)2[6] at 2311, 2281 and 1043 cm-1. Vibrational data were not reported in the other acetonitrile complexes of manganese triflate.[3, 7, 8] Therefore on the basis of nitrile-ligated high-spin manganese(II) spectra,[29, 30] we assign the two features at 2310 and 2281 cm-1 to modes of the bound acetonitriles. On the basis of the vibrational features of other metal triflate complexes,[1, 11] we assign the bands at 1312 and 1039 cm-1 to the asymmetric and symmetric vibration of the SO3 fragment respectively and the 1188 cm-1 band to the symmetric CF3 vibrational mode.

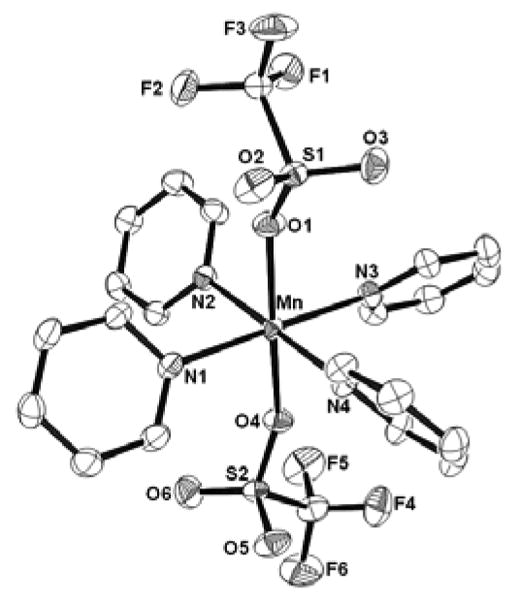

Many of the early studies of metal complexes of weakly coordinating anions examined pyridine complexes.[34, 35] Recrystallization of 1 in the presence of excess pyridine affords the pyridine complex, trans-[MnII(C5H5N)4(OTf)2], (2) (Figure 2, Table 1). The axially compressed octahedral configuration is reminiscent of that observed for trans-MnCl2(py)4.[36] The Mn-N bond distances (averaging 2.268(1) Å) are consistent with other high-spin octahedral manganese(II) pyridine distances reported.[36-40] Only here the opposing pyridine ligands are not eclipsed but in a propeller-like configuration with each pair of adjacent pyridyl rings forming dihedral angles of 67.62(7), 72.29(5), 56.51(7) and 79.07(6)°. The axial monodentate triflate anions complete the coordination sphere of the manganese(II) center. Assignment of the vibrational features is complicated by the presence of multiple pyridine ring vibrational modes for 2 (Fig. S2B).

Figure 2.

ORTEP plot of [Mn(Pyr)4(OTf)2] showing 50% probability thermal ellipsoids and the labeling scheme for unique atoms.

Both the acetonitrile and the pyridine complexes are exceedingly hygroscopic. Recrystallization in the presence of water affords colorless crystals of the hexaaquamanganese(II) salt, [MnII(H2O)6](OTf)2. Multiple formulations for the aquo adduct can be found in the literature (i.e., Mn(H2O)x(OTf)2 where x = 6, 4, or 0).[3, 6, 9, 23] We have heated this salt to 140 °C under vacuum, because earlier reports suggested decomposition at high temperatures.[3, 6] While several equivalents of water are readily removed from this aquated manganese salt, we consistently retain two broad vibrational bands at 3435 and 1626 cm-1 (Fig. S2 C and D) which we interpret as the retention of at least one water rather than the anhydrous Mn(OTf)2 salt.

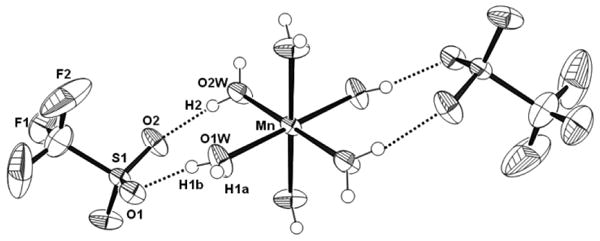

[MnII(H2O)6]2+ has been encountered in a number of structures with other complex cations and anions, but this is the first structure of the triflate salt (Figure 3, Table 1). The manganese center is located on a crystallographic inversion center. Furthermore, one of the coordinated waters is also bisected by a plane of symmetry. The other is on a general position. The distorted octahedral manganese center exhibits Mn-O bond distances (avg. 2.163 Å) which are entirely consistent with the average Mn-O bond distance of 2.17(4) Å observed in previously reported [Mn(H2O)6]2+ dications (Table S2 and accompanying references). The bond distances between the bound water molecules and the neighboring triflate anions are consistent with hydrogen-bonding interactions. These extensive hydrogen-bonding interactions order the manganese cations.

Figure 3.

ORTEP plot of [Mn(H2O)6](OTf)2 showing 50% probability thermal ellipsoids and the labeling scheme for unique atoms. Dashed lines indicate selected hydrogen-bonding interactions.

The vibrational spectrum of the aqua complex 3 exhibits easily observed features at 1261, 1179, and 1034 cm-1 which are attributed to the triflate (Figure S2 C). The feature at 1261 cm-1 is typical of an ionic triflate.[1, 11] Furthermore, the vibrational features mentioned earlier in the putative [Mn(CH3CN)4](OTf)2 do not support an outer-sphere triflate but are consistent with an inner-sphere triflate as observed in 1 and 2. The feature at 1626 cm-1 is attributed to the bending mode of coordinated water on the basis of literature precedent.[41, 42]

In summary, we have presented data on the facile preparation of three manganese(II) triflate starting materials as well as the structural characterization of each complex. Each complex is easily crystallized in high yield providing a starting material with known constitution for the many groups that utilize this material.[7, 43-45] It is also vital to protect this complex from water as hexaaquamanganese(II) triflate forms readily. IR spectra of these materials provide an inexpensive means to measure the composition of these substances. The different triflate coordination modes (whether bidentate bridging, monodentate, or outer-sphere) give rise to distinct vibrational features.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

M.P.M. thanks the University of Wyoming for start-up funds to support this work. M.P.M. thanks the University of Wyoming for start-up funds to support this work and also thanks the Wyoming NASA Space Grant Consortium, NASA Grant #NNG05G165H as well as Wyoming INBRE (Grant P20RR016474). Financial support by the NSF (CHE 0619920) for the purchase of the Bruker Apex II Diffractometer is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lawrance GA. Chem Rev. 1986;86:17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rach SF, Kuhn FE. Chem Rev. 2009;109:2061–2080. doi: 10.1021/cr800270h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon NE, Lawrance GA, Lay PA, Sargeson AM, Taube H. Inorg Synth. 1986;24:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickinson RC, Long GJ. Chem Eng News. 1970;48:6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolsey WC. J Chem Educ. 1973;50:A335–A337. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heintz RA, Smith JA, Szalay PS, Weisgerber A, Dunbar KR. Inorg Synth. 2002;33:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon J, Seo MS, Kim Y, Kim SJ, Yoon S, Jang HG, Nam W. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2009;30:679–682. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan PS, Dabrowiak JC. Inorg Chem. 1975;14:296–299. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inada Y, Nakano Y, Inamo M, Nomura M, Funahashi S. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:4793–4801. doi: 10.1021/ic000479w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng Y, Bruns JH, Moyer BA. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:209–213. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston DH, Shriver DF. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:1045–1047. [Google Scholar]

- 12.All manipulations were carried out using standard Schlenk or glove box techniques under a dinitrogen atmosphere unless otherwise noted. Preparation of [Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n, (1). TMS(OTf) (25.0 g, 113 mmol) was added dropwise to a suspension of MnCl2 (6.43 g, 51.1 mmol) in 1:1 CH3CN/THF (125 ml). After stirring overnight, the volatile materials were removed under reduced pressure. The solid was extracted with CH3CN (44 ml) and filtered through a frit. Addition of Et2O (175 ml) gave the product as a white microcrystalline solid which was dried under vacuum. Yield: 19.6 g, (45.0 mmol, 88.2%). Recrystallization from CH3CN/Et2O gives colorless diffraction quality crystals. Anal. Calcd. for [Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2], C6H6F6MnN2O6S2: C, 16.56; H, 1.39; N, 6.44; F, 26.2. Found: C, 16.90; H, 1.28; N, 6.39; F, 26.0. IR (KBr, cm-1): 2310 and 2281 (ν(CN)), 1312 (νa(SO3)), 1188 (ν(CF3)), and 1039 (νs(SO3)).Preparation of trans-[Mn(C5H5N)4(OTf)2], (2). [Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n (0.552 g, 1.27 mmol) was dissolved in acetonitile (3 ml) and pyridine (3 ml). Diffusion of diethyl ether into the solution over 1-2 days gives 0.547 g, (0.817 mmol, 64.3%) of colorless crystals suitable for XRD analysis. Anal. Calcd. for [Mn(C5H5N)4(OTf)2], C22H20F6MnN4O6S2: C, 39.47; H, 3.01; N, 8.37. Found: C, 39.39; H, 3.02; N, 8.40. IR (KBr, cm-1): 1165 (ν(CF3)), and 1033 (νs(SO3)).Preparation of [Mn(H2O)6](OTf)2 (3). [Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n (0.656 g, 1.52 mmol) was dissolved in water (10 ml). Very fragile plates grew on evaporation of the aqueous solution under atmospheric conditions. Yield: 0.686 g, (1.49 mmol, 98.0%). Anal. Calcd. for [Mn(H2O)6](OTf)2, C2H12F6MnO12S2: C, 5.21; H, 2.62. Found: C, 5.63; H, 2.43 (N, < 0.05). IR (KBr, cm-1): 3435 (ν(OH)), 1626 (δ(HOH)), 1261(νa(SO3)), 1179 (ν(CF3)), and 1034 (νs(SO3)).

- 13.[Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n, trans-[Mn(C5H5N)4(OTf)2], and [Mn(H2O)6](OTf)2 were characterized by single crystal X-ray diffraction data. Colorless crystals of the compounds were glued to MiTeGen micro-mounts using Paratone N oil and mounted on a Bruker Smart Apex II CCD diffractometer. The data were collected at 150 K using graphite-monochromated Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å) radiation. Cell parameters and orientation matrix were determined using reflections harvested from three sets of twelve 0.5° ϕ scans. For each of the data sets, optimized data collection strategies were defined using the COSMO software program (APEX 2 Software Suite v. 2.1-0, Bruker, AXS: Madison, WI, 2005). The structures were solved by direct methods using the Bruker SHELXTL (v. 6.14) software program included in the Bruker Apex 2 software package. All non-hydrogen atoms in the three structures were located in successive Fourier maps and refined anisotropically. The final full matrix least squares refinement converged to R1 = 0.0248 and wR2 = 0.0731 for [Mn(CH3CN)2(OTf)2]n, R1 = 0.0345 and wR2 = 0.0761 for trans-[Mn(C5H5N)4(OTf)2], R1 = 0.0306 and wR2 = 0.0834 for [Mn(H2O)6](OTf)2. Crystallographic data for structural analysis have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC numbers: 762443, 762444, and 762445). These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12, Union Road, Cambridge CB12 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

- 14.Churchill MR, Wasserman HJ, Turner HW, Schrock RR. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:1710–1716. [Google Scholar]

- 15.So JH, Boudjouk P. Inorg Chem. 1990;29:1592–1593. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagadorn JR, Que L, Jr, Tolman WB. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:6086–6090. doi: 10.1021/ic000531o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan MK, Armstrong WH. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4985–4986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JA, Galán-Mascarós JR, Clérac R, Sun JS, Ouyang X, Dunbar KR. Polyhedron. 2001;20:1727–1734. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comba P, Kerscher M, Merz M, Müller V, Pritzkow H, Remenyi R, Schiek W, Xiong Y. Chem Eur J. 2002;8:5750–5760. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20021216)8:24<5750::AID-CHEM5750>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubin TJ, McCormick JM, Collinson SR, Alcock NW, Clase HJ, Busch DH. Inorg Chim Acta. 2003;346:76–86. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy A, Dubois G, Stack TDP. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5250–5251. doi: 10.1021/ja029962r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britovsek GJP, England J, Spitzmesser SK, White AJP, Williams DJ. Dalton Trans. 2005:945–955. doi: 10.1039/b414813d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mossin S, Sørensen HO, Weihe H, Glerup J, Søtofte I. Inorg Chim Acta. 2005;358:1096–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gómez L, Garcia-Bosch I, Company A, Sala X, Fontrodona X, Ribas X, Costas M. Dalton Trans. 2007:5539–5545. doi: 10.1039/b712754e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nehru K, Kim SJ, Kim IY, Seo MS, Kim Y, Kim SJ, Kim J, Nam W. Chem Comm. 2007:4623–4625. doi: 10.1039/b708976g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao N, Van Stipdonk MJ, Eichhorn DM. Polyhedron. 2007;26:2449–2454. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berben LA, Peters JC. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:11669–11679. doi: 10.1021/ic801289x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Bosch I, Company A, Fontrodona X, Ribas X, Costas M. Org Lett. 2008;10:2095–2098. doi: 10.1021/ol800329m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer D, Osborn JA, Wesolek M. Polyhedron. 1990;9:1311–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vierle M, Zhang Y, Santos AM, Köhler K, Haeßner C, Herdtweck E, Bohnenpoll M, Nuyken O, Kühn FE. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:6323–6332. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du M, Zhao XJ. J Mol Struct. 2004;694:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen CL, Ellsworth JM, Goforth AM, Smith MD, Su CY, zur Loye HC. Dalton Trans. 2006:5278–5286. doi: 10.1039/b606280f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagen KS. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:5867–5869. doi: 10.1021/ic000444w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alleyne CS, Thompson RC. Can J Chem. 1974;52:3218–3228. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haynes JS, Rettig SJ, Sams JR, Thompson RC, Trotter J. Can J Chem. 1986;64:429–441. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Araya MA, Cotton FA, Matonic JH, Murillo CA. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:5424–5428. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertoncello K, Fallon GD, Murray KS. Inorg Chim Acta. 1990;174:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hübner K, Roesky HW, Noltemeyer M, Bohra R. Chem Ber. 1991;124:515–517. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soldatov DV, Lipkowski J. J Struct Chem. 1998;39:238–243. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang H, Chen Y, Li D, Wang D. Acta Crystallogr Sect E. 2007;E63:m3186. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamoto K. Organometallic and Bioinorganic Chemistry. 5. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1997. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds Part B: Applications in Coordination. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fabretti AC, Malavasi W, Rossi MC. J Crystallogr Spectrosc Res. 1993;23:313–316. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goedken VL, Busch DH. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:7355–7363. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collinson S, Alcock NW, Raghunathan A, Kahol PK, Busch DH. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:757–764. doi: 10.1021/ic981410f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Britovsek GJP, England J, White AJP. Dalton Trans. 2006:1399–1408. doi: 10.1039/b513886h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.