Abstract

Recently we developed a novel strategy for differentially painting all 24 human chromosomes. It is termed COBRA–FISH, short for combined binary ratio labeling–fluorescence in situ hybridization. COBRA–FISH is distinct from the pure combinatorial approach in that only 4 instead of 5 fluorophores are needed to achieve color discrimination of 24 targets. Furthermore, multiplicity can be increased to 48 by introduction of a fifth fluorophore. Here we show that color identification by COBRA–FISH of all of the p and q arms of human chromosomes is feasible, and we apply the technique for detecting and elucidating intra- and interchromosomal rearrangements. Compared with 24-color whole chromosome painting FISH, PQ-COBRA–FISH considerably enhances the ability to determine the composition of rearranged chromosomes as demonstrated by the identification of pericentric inversions and isochromosomes as well as the elucidation of the arm identity of chromosomal material involved in complex translocations that occur in solid tumors.

Combinatorial fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of the DNA of the 24 different human chromosomes with 5 fluorophores in conjunction with spectral or filter-based microscopic imaging (Schrock et al. 1996; Speicher et al. 1996) has greatly advanced molecular cytogenetic analysis of chromosomes (Ried et al.1998). Use of 5 fluorophores allows the identification of up to 31 different chromosomal targets on the basis of color combinations. Recently, we developed combinatorial binary ratio labeling (COBRA) FISH as an alternative multi-color FISH technique (Tanke et al. 1999), which uses 4 fluorochromes to achieve a multiplicity of 24, allowing FISH karyotyping with whole chromosomal paint probes. The multiplexing capacity of COBRA–FISH can be increased to 48 by introduction of a fifth fluorophore. Here we show that COBRA–FISH allows color discrimination of all of the p and q arms and apply the technique for detecting and elucidating intra- and interchromosomal rearrangements.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We have determined previously that with two fluorophores, five different targets are identifiable on the basis of FISH intensity ratios, that is, the ratio-resolution is at least five. Hence, by pairwise ratio labeling with 3 fluorophores, 12 ratio-labeled probes can be differentiated. To achieve higher multiplicities, the same 3 fluorophores are used to ratio label additional sets of 12 probes in an identical fashion. The sets of ratio-labeled probes are discriminated by the presence or absence of additional, spectrally distinct fluorophores referred to as binary labels. For 24-color FISH, 2 sets of 12 ratio-labeled probes and one binary label are needed, whereas for 48-color FISH, 2 binary labels are required (Tanke et al. 1999).

We reasoned that if all q arm paints, labeled with the second binary label, would efficiently hybridize simultaneously with 2 × 12 COBRA-labeled whole chromosomal paint (WCP) sets, a chromosomal region would be uniquely assigned to a given chromosome on the basis of its WCP ratio and presence or absence of the first binary label. The arm identity would then be provided by the presence or absence of the second binary label.

As shown in Figure 1, with normal metaphase chromosomes, this strategy correctly identifies p and q arms. Interestingly, sequences present in the Y paints disturbed the COBRA–FISH signals at regions of homology on the X. We observed that the tip of Xp deviates from the FISH color composition of the major part of the X chromosome. The major pseudoautosomal region PAR1 (2.6 Mb) maps to the tip of Xp (Xp22). Additionally, at Xq13, where homology with Y sequences is known to exist, Y signals were observed. Signal disturbance by Y paints was never observed at Xq28, where the minor pseudo-autosomal region maps (PAR2; 320 kb). Conversely, we similarly observed in male metaphases PAR1 at the tip of Yp, but not PAR2 on Yq.

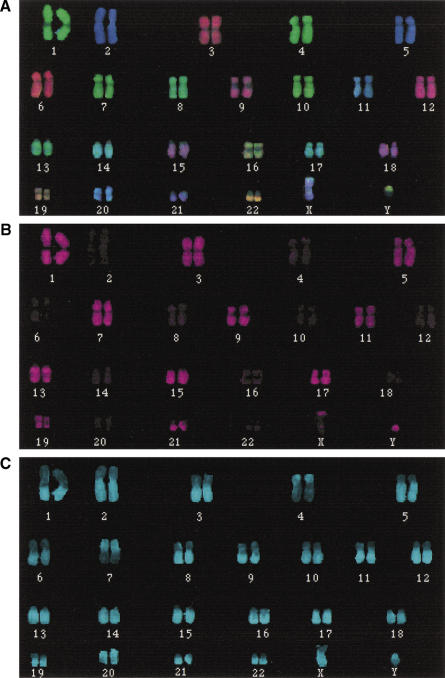

Figure 1.

Chromosomal arms differentially painted by PQ-COBRA–FISH. PQ-COBRA–FISH to normal male metaphase chromosomes. (A) shows the superimposed, pseudocolor images of the three fluorophores used for ratio labeling the WCPs in a karyogram format. The first binary label (B) differentiates the two identically ratio-labeled WCP sets. The karyogram was generated automatically on the basis of chromosomal WCP–FISH ratios and the presence (odd numbered chromosomes plus Y) or absence (even numbered chromosomes plus X) of the first binary color. The second binary label, differentiating p and q arms, is displayed in C. All q arm paints were labeled with the second binary label, except for chromosomes 4 and 7, for which p arm paints were used. Note the disturbance of the COBRA–FISH signals on the X chromosome by the Y paint.

After having established that PQ-COBRA–FISH correctly identifies all arms in normal metaphases, we applied it to the detection of intrachromosomal rearrangements and for the elucidation of a complex cancer karyotype. The two examples in Figure 2 illustrate cases of intrachromosomal rearrangements, which result in derivatives with morphologies similar to their normal homologs, and which would not be detectable by FISH without arm-specific libraries. Figure 3 exemplifies the ability to efficiently elucidate, in a single FISH experiment, rearrangements such as isochromosomes, deletions, and complex translocations in cancer karyotypes. On basis of these results and those of >20 PQ-COBRA–FISH experiments with highly complex cancer karyotypes (results not shown), we conclude that compared with 24-color chromosome painting, PQ-COBRA–FISH considerably enhances the ability to determine the composition of rearranged chromosomes.

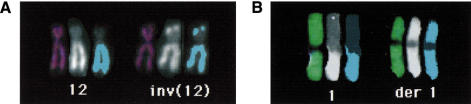

Figure 2.

Intrachromosomal rearrangements detected by PQ-COBRA –FISH. (A) An inversion of chromosome 12 in a normal carrier. In this balanced rearrangement, the distal region of the long arm is positioned on the end of the short arm of the rearranged chromosome. The segment of the short arm transferred to the long arm of the inv(12) could not be detected by us, nor in the original study by conventional cytogenetics or FISH with distal markers (Speleman et al 1993). (B) A der(1), composed exclusively of 1q material in a cervical cancer cell line with a complex karyotype. For each normal and rearranged homolog, the sequence of display is ratio image, the q arm paint (second binary label) and the thresholded image of the q-arm paint.

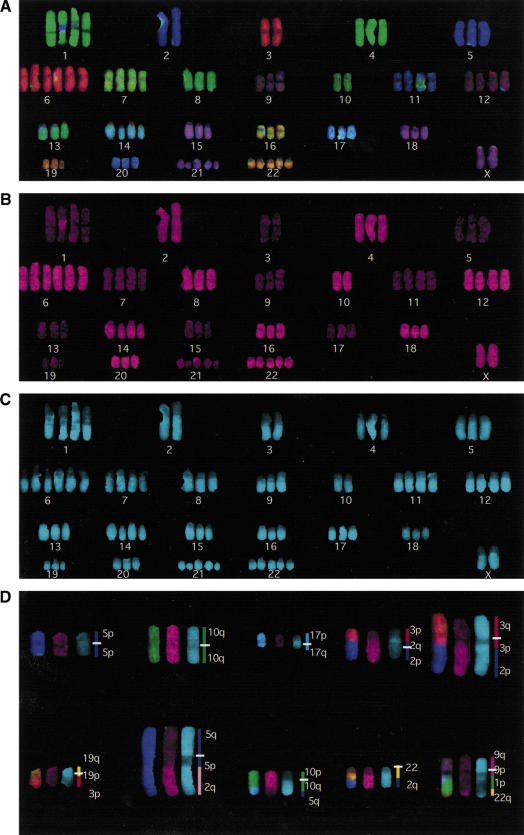

Figure 3.

PQ-COBRA–FISH of a complex cancer karyotype This near-tetraploid cancer cell shows a range of 2–6 copies of each chromosome and 10 structural rearrangements. (A,B,C) The ratio-, first- and second-binary images of PQ- COBRA–FISH of the nonrearranged chromosomes. In contrast to Fig. 1, the first binary label is on the even numbered and X chromosomes. (D) The rearranged chromosomes present in the same cell. The rearrangements include two isochromosomes, a deletion, the two products of a reciprocal translocation [t(2;3)], four unbalanced translocations involving two chromosomes, and one three-way translocation. The composition of the rearranged chromosomes is shown next to the chromosomes. The t(2;5) illustrates how the binary colors discriminate chromosome number and arm identity of chromosomes that carry the same ratio-label.

It is evident that the main advantage of COBRA–FISH—as a generic FISH technique—over mere combinatorial FISH is that with less primary fluorophores, more FISH colors can be generated. Here we have shown that by COBRA–FISH, differential painting of the p and q arms is feasible with five fluorophores only. It seems to require only small steps to reach multiplicities of 96 and 192 by introduction of additional binary fluorophores.

Ledbetter (Ledbetter 1992) discussed the cycle of technology development and application of multicolor FISH, which at that time had a multiplicity of seven (Nederlof et al. 1990; Ried et al. 1992; Wiegant et al. 1993). Ledbetter predicted correctly that further development of FISH methodology as well as hard- and software for digital imaging should allow simultaneous visualization of 24 chromosomes in different colors. Here we have shown that 48-color FISH is feasible. It is likely that further cycles of technology development and application will push FISH multiplicity further, possibly to a point that high-resolution, molecular-banding procedures by FISH can be developd.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA Labeling and FISH

WCP-DNAs were obtained from Cytocell (Banbury, UK) or kindly donated by Nigel Carter (Sanger Center, Cambridge, UK). Chromosome arm-specific paints were generated by microdissection and DOP–PCR as described (Guan et al. 1996). For labeling the WCPs and arm paints, we used either chemical ULS labeling after DOP–PCR or enzymatic labeling during DOP–PCR. Results obtained with both labeling methods were identical. For example, the ULS experiment of Figure 1 was initially performed with enzymatically labeled probes with identical results. For chemical ULS labeling, the WCP sets and the arm paints were labeled in five separate labeling reactions. To this end, optimized amounts of each unlabeled (DOP–PCR amplified) paint destined to get the same ULS label were mixed and reacted with the appropriate ULS label. After Qiagen column purification, the five labeled DNA solutions were mixed and a 3× excess of human Cot-1 DNA was added. After ethanol precipitation, the DNA was dissolved in a hybridization mixture. Subsequent FISH was as described previously (Tanke et al. 1999), with the exception that hybridization times were reduced from 5 to 2 days. For ratiolabeling, we used Diethylaminocoumarin (DEAC)-ULS, Cy3-ULS, and Cy5-ULS. As first and second binary ULS labels, OregonGreen- and dinitrophenyl (DNP)-ULS were used. All ULS labels were generous gifts from Kreatech BV (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The DNP moiety was visualized with a biotinated anti-DNP antibody and LaserPro IR790-conjugated Streptavidin (Molecular Probes).

For enzymatic labeling, each probe was labeled separately by incorporating the requisite labeled dUTP during DOP–PCR. Optimized amounts of Qiagen column-purified DNA were mixed, Cot-1 DNA was added, and after ethanol precipitation, the probe mix was dissolved in hybridization solution. Fluorescein-dUTP, Lissamine-dUTP, and Cy5-dUTP were used for ratio labeling WCPs. Dig-dUTP and biotin-dUTP were used as first and second binary labels. Dig was detected with mouse monoclonal anti-dig and a DEAC-conjugated anti-mouse Ig. The imaging and image processing of the WCP-COBRA–FISH was essentially as described previously (Tanke et al 1999). For imaging the second binary label (LaserPro), an extra filter set [(excitation and emission maxima at 740, respectively, 780 nm (Omega)] was used.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Frank Speleman for the inv(12) case, Karoly Szuhai for stimulating discussions, and Marja de Wind for technical assistance. This work was partially supported by the EUREKA program (SPEKTRAKAR) of Applied Imaging (Newcastle, UK) and Kreatech Diagnostics BV (Amsterdam, the Netherlands).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL a.k.raap@lumc.nl; FAX 31-71-5276180.

REFERENCES

- Guan XY, Zhang H, Bittner M, Jiang Y, Meltzer P, Trent J. Chromosome arm painting probes. Nat. Genet. 1996;12:10–12. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledbetter D. The ‘colorizing’ of cytogenetics: Is it ready for prime time. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:297–299. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.5.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nederlof PM, van der Flier S, Wiegant J, Raap AK, Tanke HJ, Ploem JS, van der Ploeg M. Multiple fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cytometry. 1990;11:126–131. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990110115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ried T, Baldini A, Rand TC, Ward DC. Simultaneous visualization of seven different DNA probes by in situ hybridization using combinatorial fluorescence and digital imaging microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:1388–1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ried T, Schrock E, Ning Y, Wienberg J. Chromosome painting: A useful art. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1619–1626. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.10.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrock E, du Mamoir S, Veldman T, Schoell B, Wienberg J, Ferguson-Smith MA, Ning Y, Ledbetter DA, Bar-Am I, Soenksen D, Garini Y, Ried T. Multicolor spectral karyotyping of human chromosomes. Science. 1996;273:494–497. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speicher MR, Gwyn BS, Ward DC. Karyotyping human chromosomes by combinatorial multi-fluor FISH. Nat Genet. 1996;12:368–375. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speleman F, Van Roy N, De Vos E, Hilliker C, Suijkerbuijk RF, Leroy JG. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of a familial pericentric inversion of chromosome 12. Clin Genet. 1993;44:156–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1993.tb03869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanke HJ, Wiegant J, Van Gijlswijk RPM, Bezrookove V, Pattenier H, Heetebrij RJ, Talman EG, Raap AK, Vrolijk J. New strategy for multi-colour fluorescence in situ hybridisation. COBRA: COmbined Binary RAtio labelling. Eur J Hum Genet. 1999;7:2–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegant J, Wiesmeijer CC, Hoovers JMN, Schuuring E, d'Azzo A, Vrolijk J, Tanke HJ, Raap AK. Multiple and sensitive fluorescence in situ hybridization with rhodamine-, fluorescein-, and coumarin-labeled DNA's. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1993;63:73–76. doi: 10.1159/000133507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]