Abstract

The link between impaired maternal behavior (MB) and cocaine treatment could result from drug-induced decreases in maternal reactivity to offspring, prenatal drug exposure (PDE) in offspring that could alter their ability to elicit MB, or the interaction of both, which could subsequently impair MB of the 1st-generation dams. Following chronic or intermittent cocaine or saline treatment during gestation, rat dams rearing natural or cross-fostered litters were compared along with untreated dams for MB. Untreated 1st-generation females with differentially treated rearing dams and PDE were tested for MB with their natural litters. The authors report disruptions in MB in dams and their 1st-generation offspring, attributable to main and interaction effects of maternal treatment, litter PDE, and rearing experience.

Keywords: maternal behavior, intergenerational, rearing, prenatal, oxytocin

Pregnant women who use cocaine perpetrate child abuse and neglect more often than women who do not use cocaine during pregnancy (Hawley, Halle, Drasin, & Thomas, 1995; Tyler, Howard, Espinosa, & Doakes, 1997; Wasserman & Leventhal, 1993). Maternal cocaine abuse during pregnancy has also been strongly associated with deficits in maternal–infant bonding (Burns, Chethik, Burns, & Clark, 1991), and mothers with a history of substance abuse often exhibit poor mother–infant interactions (Bauman & Dougherty, 1983; Bays, 1990; Howard, Beck-with, Espinosa, & Tyler, 1995; Johnson & Rosen, 1990). Though studies with human participants are helpful in understanding the connection between cocaine use and maternal neglect, these experiments are correlational. There is a necessary lack of control over many important variables that could confound the results, such as socioeconomic issues, lack of family support, multidrug abuse, and poor general prenatal care (Chasnoff et al., 1998; Koren et al., 1998). Studies that use numerous controls have shown a strong correlation between reported history of child maltreatment and the perpetration of maltreatment and/or neglect in next-generation mothers (Egeland, Jacobvitz, & Papatola, 1987; Hunter, Kilstrom, Kraybill, & Loda, 1978).

In order to appropriately investigate and describe the characteristics of cocaine-induced disruption of maternal behavior and potential neglect, as well as possible intergenerational effects of such disruptions, a nonhuman cocaine abuse model offers several advantages. The laboratory rat is a particularly good model for the study of maternal behavior. Their offspring are born blind, unable to thermoregulate, defecate, urinate, or protect themselves from attack (Numan, 1994), thus needing considerable maternal care to survive (Stern, 1997). Behaviorally and neurologically, maternal behavior in the rat has also been relatively well characterized (Numan, 1994; Pedersen, Ascher, Monroe, & Prange, 1982; Pedersen, Caldwell, Walker, Ayers, & Mason, 1994) so that any insult to normal maternal behavior can be easily determined.

Maternal separation studies also support a rat intergenerational model of behavior showing that cross-fostering results in behavior of offspring similar to behavior of rearing dams, suggesting a nongenetic transmission of behavior (Francis, Diorio, Liu, & Meaney, 1999; Liu, Caldji, Sharma, Plotsky, & Meaney, 2000), which among other data led us to investigate the presence of intergenerational effects of cocaine use.

As far as the literature to date, there is general agreement that acute cocaine treatment in rat dams disrupts both early onset and established pup-directed maternal behavior, while increasing locomotor behavior and stereotypies (Johns, Nelson, et al., 1998; Johns, Noonan, Zimmerman, Li, & Pedersen, 1994; Kinsley et al., 1994; Zimmerberg & Gray, 1992). Significant disruptions in maternal behavior following chronic gestational cocaine treatment during pregnancy were reported for the onset or very early post-partum period, and these dams did not display the hyperactivity often seen in acutely treated dams (Heyser, Molina, & Spear, 1992; Johns, Noonan, et al., 1994; Kinsley et al., 1994; Peeke, Dark, Salamy, Salfi, & Shah, 1994; Vernotica, Lisciotto, Rosenblatt, & Morrell, 1996). No reports, to our knowledge, have been published on intermittent gestational and postpartum cocaine treatment or the intergeneration effects of such treatment on maternal behavior.

In previous studies, dams treated with cocaine gestationally were also found to exhibit differences in oxytocin system dynamics (Johns et al., 1995; Johns, Lubin, Walker, Meter, & Mason, 1997; Johns, Nelson, et al., 1998; Johns, Noonan, et al., 1994; Lubin, Elliott, Black, & Johns, 2003). Oxytocin is an important neuroendocrine system implicated in normal maternal behavior onset in rats (Fuchs, 1983; Pedersen et al., 1982; Pedersen, Caldwell, Johnson, Fort, & Prange, 1985; Pedersen et al., 1994) and therefore likely to be implicated when this behavior is disrupted (Pedersen et al., 1985; Van Leengoed, Kerker, & Swanson, 1987). One study looking at rodent maternal behavior suggested that differences in oxytocin levels in brain regions implicated in maternal behavior may be affected intergenerationally (Pedersen & Boccia, 2002). It is important to determine whether cocaine-induced disruptions in maternal behavior influence next-generation maternal behavior and whether those behavioral changes correlate with oxytocin system changes as they do in the parent dam.

The present study was designed to answer important questions about whether gestational and intermittent (pre- and postpartum) cocaine treatment differentially alter maternal behavior; how pre-natal exposure condition of litters’ and the dams’ drug treatment interact to influence maternal behavior, and whether altered maternal behavior onset and oxytocin system changes are apparent in first-generation females as a result of either their prenatal drug exposure condition or their rearing environment. We hypothesized that there would be altered onset of maternal behavior in chronically and intermittently cocaine treated mothers, primarily due to drug treatment, and that disruptions would diminish across the postpartum period as the role of oxytocin in these behaviors presumably decreased. It was hypothesized that following an injection of cocaine 30 min prior to testing on Postpartum Day (PPD) 15, the intermittently injected cocaine dams would show full disruption of maternal behaviors similarly to that reported in previous studies following acute cocaine treatment (Johns, Noonan, et al., 1994; Zimmerberg & Gray, 1992). With respect to prenatal exposure condition of litters, we predicted that cocaine treated dams rearing cocaine exposed pups would exhibit the strongest disruption of maternal behavior. We hypothesized that the onset of maternal behavior in first-generation dams (FGDs) would be altered primarily by prenatal cocaine exposure, with secondary effects resulting from the rearing dams’ treatment. FGDs reared by chronic and intermittent cocaine-treated dams were expected to exhibit more disruptions in maternal behavior than those reared by untreated dams.

If maternal behavior continued to be impaired by chronic cocaine treatment on PPD 15, we predicted there would be a diminished oxytocin response in the medial preoptic area (MPOA) on PPD 22, but that if behavioral differences were not apparent, we would see no differences between groups with respect to oxytocin levels. Finally, we hypothesized that oxytocin levels in FGDs that displayed significant disruptions in maternal behavior based on rearing by cocaine-treated dams or prenatal cocaine exposure would be decreased in a similar manner as that previously seen in cocaine treated dams following the onset of maternal behavior (Johns et al., 1997).

Method

Subjects

Following a 2-week habituation period, virgin female (200–240 g) Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River, Raleigh, NC) were placed with males on a breeding rack until a sperm plug was found, which was designated as Gestation Day (GD) 0. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of five treatment or control groups and singly housed and maintained on a reversed 12-hr light–dark cycle (lights off at 0900) for 7 days. They were then transferred to a room with a regular light cycle (lights on at 0700) for the remainder of the experiment, a procedure that generally results in the majority of dams delivering their litters during daylight hours (Mayer & Rosenblatt, 1998).

Treatment groups included chronic cocaine (CC), intermittent cocaine (IC), chronic saline (CS), intermittent saline (IS), and untreated (UN) dams. CC and CS dams received subcutaneous injections twice daily throughout gestation (GD 1–20), on alternating flanks, of 15 mg/kg cocaine HCL (dose calculated as the free base; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 0.9% normal saline (total volume 2 ml/kg), or normal saline (0.9%) respectively, at approximately 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. IC-treated dams received the same dose and volume of cocaine as the CC dams except their injections occurred on 2 consecutive days only, every 5 days during gestation (GD 2, 3, 8, 9, 14, 15, and 20) and on the same respective days during the postpartum period. IS-treated dams received normal saline (0.9%) on the same injection schedule as the IC dams. The intermittent schedule was modeled after a previous study examining behavioral effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on offspring (Johns et al., 1992). UN dams were weighed and handled daily but received no drug treatment. All treatment groups had free access to water and food (Rat Chow), except that the CS treated dams were pair fed to match CC dams in order to control for the anorexic effects of cocaine, as previously described (Johns, Noonan, et al., 1994). All procedures were conducted under federal and institutional animal care and use committee guidelines for humane treatment of laboratory subjects.

Cross-Fostering

On the day of parturition, pups were removed from each dam, weighed, counted, and their gender determined before being culled to a litter of 4 males and 4 females. Litters were culled 30 min before testing and either returned at time of testing to their natural mothers or fostered to dams from a different treatment or control group having delivered as closely as possible to the same time (usually within several hours). Dams and their litters were matched for delivery time and cross-fostering interval in all groups. The cross-fostering procedure resulted in the dam–offspring group combinations shown in Table 1. Group numbers varied somewhat because of the loss of some rats during testing and the necessity of breeding extra dams to deliver at specific times to allow fostering of specific groups. Cross-fostering allowed for independent assessment of the effects of pre-natal drug exposure of a rearing litter and the effects of maternal drug treatment (or the interaction of these conditions) on maternal behavior in original test dams on PPDs 1, 5, 10, and 15. We were also able to determine the effects of prenatal drug exposure, as well as the effects of treatment condition of the rearing mother, on the maternal behavior of first-generation offspring dams. In order to achieve sample sizes large enough within each of the 25 groups for assessment with parametric statistics, this study required 4 years to complete with hundreds of offspring born each spring. Each year, the same treatment and testing procedures were repeated in a new group of dams and their offspring, which, although a practical necessity, also introduced some variability resulting from year of testing. This variability induced by year of testing was randomly spread across groups and did not influence group differences differentially over the 4 years.

Table 1.

Experimental Groups Resulting from Cross-Fostering

| Litter prenatal exposure condition | Rearing dam treatment

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | IC | CS | IS | UN | |

| cc | CCcc (13/10) | ICcc (13/12) | CScc (14/11) | IScc (14/10) | UNcc (12/10) |

| ic | CCic (12/10) | ICic (15/12) | CSic (12/10) | ISic (14/11) | UNic (15/11) |

| cs | CCcs (15/10) | ICcs (14/11) | CScs (13/11) | IScs (13/10) | UNcs (13/10) |

| is | CCis (13/10) | ICis (13/10) | CSis (14/11) | ISis (16/14) | UNis (12/10) |

| un | CCun (11/11) | ICun (15/13) | CSun (16/10) | ISun (19/17) | Unun (28/23) |

Note. Capital letters indicate the original or parent dams’ treatment; lowercase letters indicate the prenatal exposure condition of first generation dams (FGDs). Group designations are as follows throughout tables chronic cocaine (CC), chronic saline (CS), intermittent cocaine (IC), intermittent saline (IS), or no treatment (UN). The total numbers of original dams (ODs) and first generation dams (FGDs) for each group are listed in parentheses. Group sizes varied as a result of extra breeding for testing purposes and loss of dams for various reasons during the study.

Original Dam Maternal Behavior Testing

The procedure for maternal behavior testing was previously described (Johns, Noonan, et al., 1994). Following delivery of their final pup, dams and their litters were brought in their home cage to an enclosed behavioral observation room, 400 × 460 cm, where dams were removed from their cage and weighed, and their pups removed. Dams were placed back in their home cages without pups, and the cages were placed in a 60.96 cm high × 40.64 cm wide × 50.80 cm deep dimly lit testing cubicle, designed to reduce environmental distractions, for a 30-min habituation period. During the habituation period, litter measurements were taken and litters were culled to 4 female and 4 male pups. Then, either her natural litter or a foster litter culled at the same time was placed in a warm (room temperature) plastic cage lined with paper towels on top of the dam’s testing cubicle. After habituation, nesting material (ten 2.54-cm strips of paper towel) was placed at the back of the cage and each dam’s culled litter (fostered or natural) was placed in the front of her cage. Videotaping with a Panasonic VHS (AG188U) recorder with low light sensitivity began as soon as the pups were placed in the cage and continued for 30 min on PPD 1. After testing, dams and their culled litters were returned to the colony room until the next testing session (PPD 5). On PPD 5, 10, and 15, the testing procedure for maternal behavior was the same, excepting that after PPD 1, each dam kept her litter assigned on PPD 1 throughout the entire study until weaning, and maternal behavior was only recorded for a 15-min period. We reduced the test time after PPD 1 because we found in pilot studies that group differences were still apparent with a 15-min test period, and that scoring all sessions for 30 min was very labor intensive and thus prohibitive. In addition, on PPD 15, IC and IS dams (only) were injected with cocaine (15 mg/kg) or saline, respectively, after weighing at the beginning of the 30-min habituation period, as PPD 15 was part of their intermittent injection schedule. Recorded sessions from PPD 1, 5, and 10 were later analyzed for frequency, duration, and latency of the following 11 behaviors: nest build (dam manipulates or moves the paper strips with her mouth or paws), touch–sniff pups (dam touches pups with her nose or front paws or sniffs them), retrieve 2 pups (dam has carried 2 pups from the front to the rear of the cage), self-groom (dam grooms herself with her tongue or paws), rest off–lie on (dam rests away from the pups or lies flat on top of them in a nonfeeding position), crouch (dam stands over the pups with back arched in the nursing position, legs stiff and straight, and head lowered), retrieve 6 pups (dam has carried 6 pups from the front to the rear of the cage), lick pup (dam licks a pup), retrieve 8 pups (dam has carried all 8 pups from the front to the rear of the cage), rear–sniff (dam rears on hind legs and sniffs the cage or air), and other (any behavior other than those designated).

On PPD 15, some new behaviors were added, some dropped, and others redefined to allow for the increased size and locomotor ability of pups. Changes included removal of the standard retrieval measures, and new designations including separate categories for rest off (dam lies away from pups) and lie on (dam lies flat on top of pups in a nonfeeding position); an expanded definition of nursing, renamed crouch–feed (dam crouches or she allows suckling while lying on her side or back); as well as several measures of pup grouping designated as pups together (first time in session that 8 pups are together in rear of cage) and group pups (dam picks up at least 1 pup and puts it with another pup). Nest build, touch–sniff pups, lick pup, rear–sniff, self-groom, and other were defined as they had been for previous test days. Behaviors on all sessions were mutually exclusive so that only one behavior could be recorded at a time, and crouching took precedence so that if dams were simultaneously crouching and licking or crouching and nesting, crouching would be the recorded behavior.

At the end of each maternal behavior test, dams and their culled litters were returned to the colony. Dams remained with their pups until weaning on PPD 21. On PPD 22, dams were killed by decapitation and their brains removed and dissected for an oxytocin radioimmunoassay (RIA) procedure.

FGDs

After weaning on PPD 21, offspring were housed in same-sex litters of 4 males and 4 females. One female from each litter was randomly selected at 60 days of age for breeding and testing for the onset of maternal behavior on PPD 1. Remaining pups from the litters were used for other behavioral tests at various ages (not reported here). Breeding conditions were the same as with the original treatment dams except that they received no drug treatment, were tested with their natural litters, were bred to different males, and were fed ad libitum. FGDs were assigned group designations based on their prenatal exposure condition and their rearing dams’ drug treatment (e.g., CCCS indicates that the dam that reared the FGD was CC treated but the dam she was born to was treated gestationally with CS; thus, she was prenatally exposed to saline). FGDs were weighed every 5 days to monitor weight gain throughout pregnancy.

First-Generation Maternal Behavior Testing

On the day of expected delivery, FGDs were monitored throughout the day until delivery of their final pup, at which time their natural litters were culled to four males and four females for maternal behavior testing. Testing procedures for FGDs were essentially the same as for the original parent dams on PPD 1, except there was no cross-fostering. At the end of the 30-min behavioral test, dams and their culled litter were returned to the colony until the following morning (PPD 2), when FGDs were killed by decapitation and their brains were removed and dissected for an oxytocin RIA procedure.

Brain Dissection

Following decapitation, the whole MPOA, hippocampus, amygdala, and ventral tegmental area (VTA) regions were dissected on ice, weighed, rapidly frozen, and stored at −80 °C for later RIA. RIA brain dissection procedures were previously described (Johns et al., 1997). Brains were coronally sectioned from the ventral side rostral to the optic chiasm (approximately A7100 μm, according to Konig & Klippel, 1963) and just caudal to the optic chiasm (approximately A5800 μm) to define the preoptic-anterior hypothalamic area. Vertical cuts inferior to the lines of lateral ventricles and a horizontal cut ventral to the anterior commissure were made to produce a block section of the MPOA. The brains were sectioned once again just caudal to the tuber cinereum (approximately A3800 μm) and slightly above the cerebellum and the amygdala was removed in this section, the VTA was dissected from the caudal section by making dorsoventral cuts medial to the optic tracts with a dorsal cut at the ventral extent of the central gray, and the whole hippocampus was then removed from the caudal remainder of the brain.

Oxytocin RIA

Brain region tissues were homogenized in cold buffer (19 mM monobasic sodium phosphate, 81 mM dibasic sodium phosphate, 0.05M NaCl, 0.1% BSA, 0.1% Triton 100, 0.1% sodium azide, pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 3,000 g for 30 min. Oxytocin immunoreactive content was assayed in the supernatant according to a protocol from Peninsula Labs (Belmont, CA). Samples and standards (1.0–128.0 pg) were incubated in duplicate for 16 to 24 hr at 4 °C with rabbit antioxytocin serum. They were then incubated for 16 to 24 hr at 4 °C with 125I-Oxytocin after which time normal rabbit serum and goat antirabbit IgG serum were added and incubated 90 min at room temperature. The 125I-Oxytocin bound to the antibody complex was separated from free by a 90-min centrifugation at 4 °C. The radioactivity in the pellet was measured using a LKB CliniGamma counter (PerkinElmer Wizard 1470-005), which calculates the picogram content of oxytocin in each sample from the standard curve. The intraassay coefficient of variance (CV) was 4.05%, and interassay CV was 8.95%. The sensitivity of the assay was approximately 0.5 pg/tube. Picograms of oxytocin per milligram of tissue were analyzed and compared for differences between groups using analyses of variance (ANOVAs) followed by post hoc Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) tests with significance set at p ≤ .05.

Behavioral Data Analyses

Videotaped sessions were scored by two independent observers blind to treatment condition with inter- and intrareliability set at 95% to 100% concurrence for frequency and latency and 80% or better for duration of behaviors displayed by the dam, using a computer program that calculated the frequency, duration, and latency of all relevant behaviors displayed by the dams. Behaviors not displayed by the dam were assigned a frequency and duration of 0 and the highest possible latency (1,800 s for a 30-min test, 900 s for a 15-min test).

Statistical Analyses

Two-factor (Drug Treatment × Litter Prenatal Exposure) between-groups ANOVAs were used for original dams and first-generation offspring (Prenatal Exposure Condition × Rearing Dam treatment) on PPD 1. Test durations for PPDs 5, 10, and 15 were only 15 min, so the data could not be directly compared to PPD 1. Repeated measures ANOVAs were used for original dams on PPDs 5 and 10 for between- and within-groups differences (Drug Treatment × Litter Prenatal Exposure). A two-factor between-groups ANOVA (as used for PPD 1) was also used for PPD 15 data, as the behavioral categories were different from those on previous test days. We found no systematic group differences based on year of testing. Tukey HSD tests were used for post hoc analyses, and statistical significance was set at less than or equal to the .05 level with relevant trends acknowledged in the Results or Discussion sections. The mean and standard error of the mean for measures of behaviors that were significantly different or of particular interest are presented in the tables as pup-directed maternal behavior (crouch, lick pups, nest build) or nonmaternal behaviors (rest off–lie on, other, rear–sniff, self-groom). Effects on maternal behavior of original dams as a result of drug treatment across PPDs, effects based on their rearing litter condition (litter prenatal exposure), and interaction effects (dam treatment by prenatal litter condition) are presented. Effects on FGD maternal behavior are presented based on prenatal exposure condition, rearing condition (treatment of rearing dam), and interaction effects (rearing condition by prenatal exposure condition). Oxytocin data for original dams and FGDs are presented last. Comparisons for the original dams are divided into subsets of relevant groups including chronically treated and untreated groups (CC, CS, UN), intermittently treated and untreated groups (IC, IS, UN), and finally differences between cocaine treated groups only (CC, IC) where relevant. When possible, references are made to tables for individual post hoc values with overall F values and general statements of results detailed in text.

Results

Original Dams: Gestational Variables

Gestational weight gain and litter variables for PPD 1 are presented in Table 2. There were significant effects of dam treatment on gestational weight gain, F(4, 354) = 20.95, p ≤ .01, and litter birth weight, F(4, 360) = 2.75, p ≤ .03. Lower birth weight litters in the CC, IC, and CS treated dams were probably the result of both cocaine treatment and slightly fewer pups (CC, CS) because there were no significant differences between groups in the average weight per pup.

Table 2.

Maternal Litter Data for Original Dam Treatment Groups

| Dam gestational treatment | Number of dams | Gestational weight gain (g) | Whole litter weight (g) | Number of pups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 67 | 134.8 ± 2.6UC | 86.3 ± 2.0u | 14.3 ± 0.4 |

| CS | 71 | 132.3 ± 2.5 U | 85.3 ± 1.9u | 13.5 ± 0.3 |

| UN | 81 | 157.7 ± 2.4 | 91.5 ± 1.8 | 14.5 ± 0.3 |

| IC | 70 | 147.4 ± 2.5 sU | 89.6 ± 1.9 | 14.4 ± 0.3 |

| IS | 77 | 154.4 ± 2.4 | 92.3 ± 1.8 | 14.6 ± 0.3 |

Note. Means with capitalized letters differ at p ≤ 0.01 while lowercase letters differ at p ≤ 0.05. Different letters indicate differences as follows: S(s) indicates groups significantly different from respective saline control, U(u) indicate groups significantly different from UN treated dams, and C(c) indicates significant difference between cocaine treated groups (CC and IC).

Original Dams: Dam Treatment Effects

PPD 1—Significant Behavioral Effects

There were significant effects of dam treatment on the duration of crouching, F(4, 331) = 4.24, p ≤ .01; nest building, F(4, 332) = 4.12, p ≤ .01; and self-grooming, F(4, 333) = 2.65, p ≤ .03; the frequency of nest building, F(4, 333) = 2.59, p ≤ .04; self-grooming, F(4, 333) = 3.51, p ≤ .01; rear–sniff, F(3, 333) = 2.71, p ≤ .03; and other, F(4, 333) = 2.57, p ≤ .04; and on the latency to begin nest building, F(4, 333) = 3.28, p ≤ .01. The mean and standard error of the mean are presented for relevant behaviors for all groups in Table 3.

Table 3.

Original Dams PPD 1 Maternal Behavior: Dam Treatment Effects

| Pup-directed maternal behaviors | Dam treatment

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CS | UN | IC | IS | ||

| Crouch | Frequency | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 0.6 |

| Duration (s) | 495.6 ± 66.6SU | 731.6 ± 64.4 | 822.0 ± 62.5 | 624.4 ± 63.9 u | 788.1 ± 61.3 | |

| Latency (s) | 839.3 ± 78.9 | 497.0 ± 76.4 | 362.2 ± 74.1 | 543.0 ± 75.2 | 513.1 ± 72.7 | |

| Lick pups | Frequency | 5.8 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.6 |

| Duration (s) | 76.1 ± 11.0 | 35.3 ± 10.6 | 57.0 ± 10.2 | 69.2 ± 10.5 | 50.1 ± 10.1 | |

| Latency (s) | 517.5 ± 91.6 | 597.3 ± 88.7 | 787.8 ± 85.1 | 631.2 ± 87.3 | 670.5 ± 84.4 | |

| Nest-build | Frequency | 11.9 ± 1.7 | 10.8 ± 1.7 | 9.2 ± 1.6 | 14.9 ± 1.7 su | 8.1 ± 1.6 |

| Duration (s) | 115.5 ± 15.4 u | 75.5 ± 14.9 | 68.2 ± 14.3 | 126.3 ± 14.7 su | 59.7 ± 14.2 | |

| Latency (s) | 316.7 ± 82.6 u | 443.9 ± 79.9 | 572.9 ± 76.7 | 511.3 ± 79.7 | 700.9 ± 76.0 | |

|

| ||||||

| Nonmaternal behaviors | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Self-groom | Frequency | 5.8 ± 0.4 Suc | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 |

| Duration (s) | 94.9 ± 9.0 Suc | 54.2 ± 9.2 | 62.3 ± 8.9 | 67.4 ± 9.1 | 70.4 ± 8.8 | |

| Latency (s) | 484.8 ± 59.0 | 574.7 ± 57.1 | 495.9 ± 54.8 | 447.8 ± 56.3 | 465.8 ± 54.4 | |

| Rear-sniff | Frequency | 14.5 ± 1.2 uc | 11.6 ± 1.2 | 10.6 ± 1.1 | 9.6 ± 1.2 | 10.2 ± 1.1 |

| Duration (s) | 59.1 ± 8.0 | 51.9 ± 7.8 | 56.6 ± 7.5 | 39.2 ± 7.6 | 42.3 ± 7.4 | |

| Latency (s) | 102.8 ± 36.9 | 124.2 ± 35.7 | 88.4 ± 34.3 | 126.8 ± 35.1 | 143.0 ± 34.0 | |

| Other | Frequency | 54.8 ± 2.3 su | 45.7 ± 2.7 | 43.5 ± 2.6 | 49.0 ± 2.3 | 45.8 ± 2.6 |

| Duration (s) | 536.0 ± 38.5 | 451.8 ± 37.2 | 450.3 ± 36.1 | 440.1 ± 36.7 | 442.8 ± 35.4 | |

| Latency (s) | 11.7 ± 3.5 | 5.8 ± 3.4 | 5.9 ± 3.2 | 11.5 ± 3.3 | 10.6 ± 3.2 | |

Note. Means with capitalized letters differ at p ≤ 0.01 while lowercase letters differ at p ≤ 0.05. Different letters indicate differences as follows: S(s) indicates groups significantly different from respective saline control, U(u) indicate groups significantly different from UN treated dams, and C(c) indicates significant difference from cocaine treated groups (CC and IC).

Chronically treated (CC, CS) and untreated dams (UN)

CC treated dams crouched less (frequency p < .06; duration p < .01) than both CS and UN treated dams and had a longer duration of (p ≤ .03) and shorter latency (p ≤ .02) to nest building than UN treated dams. CC treated dams also spent more time performing non-pup-directed behaviors (self-groom, other, rear–sniff) than CS and UN treated dams (p ≤ .01) and touched and retrieved pups later as well nonsignificant (ns).

Intermittently treated (IC, IS) and untreated dams (UN)

IC treated dams crouched for a shorter duration than UN dams (p ≤ .03) but built nests more frequently (p ≤ .01) and longer (p ≤ .03) than IS and UN treated dams.

Cocaine treated (IC vs. CC) dams

CC treated dams groomed themselves more often (p ≤ .05) and longer (p ≤ .04) and rear–sniffed more than IC treated dams (p ≤ .02).

PPD 5 and 10 Repeated Measures—Significant Between-Groups and Within-Group Effects

All mean and standard error of the mean values for categories having within- or between-groups differences for dam treatment on PPD 5 or 10 are displayed in Table 4 with significant post hoc values indicated. There were significant between-groups main effects of dam treatment on the frequency, F(4, 321) = 2.72, p ≤ .05, and latency, F(4, 321) = 3.11, p ≤ .05, of nest building, and on the duration, F(4, 321) = 2.77, p ≤ .01, and latency, F(4, 321) = 2.38, p ≤ .05, of self-grooming on PPD 5. There were also significant between-groups effects of dam treatment on the frequency, F(4, 321) = 2.72, p ≤ .05, of nest building and duration of self-grooming, F(4, 321) = 2.77, p ≤ .01, on PPD 10. IC and CS treated dams tended to nest build sooner and more frequently, whereas the IC treated dams spent more time grooming themselves (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Original Dam PPD 5 and 10 Maternal Behavior: Dam Treatment Repeated Measures

| Pup-directed maternal behaviors | Dam treatment | Frequency

|

Duration (s)

|

Latency (s)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPD

|

PPD

|

PPD

|

|||||

| 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Crouch | CC | 6.2 ± 0.7 W | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 177.0 ± 27.9 | 217.9 ± 30.4 | 403.3 ± 44.2 | 421.5 ± 46.6 |

| CS | 6.2 ± 0.7 W | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 169.3 ± 27.3 | 191.7 ± 29.8 | 402.7 ± 43.3 | 433.1 ± 45.6 | |

| UN | 6.4 ± 0.7 w | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 208.5 ± 27.3 | 256.7 ± 29.8 | 397.5 ± 43.3 | 441.6 ± 45.6 | |

| IC | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 6.0 ± 0.6 W | 181.2 ± 27.6 | 272.0 ± 30.1 | 405.2 ± 43.8 | 362.1 ± 46.1 | |

| IS | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 230.9 ± 26.8 | 237.0 ± 29.2 | 339.3 ± 45.4 | 377.6 ± 44.7 | |

| Lick pups | CC | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 7.7 ± 0.9 | 35.6 ± 6.1 | 93.1 ± 12.7 | 422.5 ± 44.8 | 254.7 ± 40.4 |

| CS | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 8.4 ± 0.9 | 27.7 ± 6.0 | 99.0 ± 12.4 | 503.1 ± 43.9 | 225.0 ± 39.5 | |

| UN | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 22.9 ± 6.0 | 91.5 ± 12.4 | 538.4 ± 43.9 | 315.4 ± 39.5 | |

| IC | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 20.8 ± 6.1 | 65.7 ± 12.6 | 527.7 ± 44.4 | 298.6 ± 40.0 | |

| IS | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 7.8 ± 0.9 | 21.6 ± 5.9 | 83.2 ± 12.2 | 466.0 ± 43.0 | 204.3 ± 38.7 | |

| Nest-build | CC | 11.2 ± 1.2 | 7.5 ± 1.0 | 49.9 ± 8.3 | 40.9 ± 7.6 | 271.4 ± 27.3 | 340.2 ± 36.4 |

| CS | 13.1 ± 1.2 u | 9.5 ± 1.0 u | 71.6 ± 8.1 | 40.5 ± 7.4 | 138.9 ± 27.0UC | 316.8 ± 35.6 | |

| UN | 9.9 ± 1.2 | 6.4 ± 1.0 | 49.7 ± 8.1 | 23.5 ± 7.4 | 235.7 ± 26.7 | 340.4 ± 35.6 | |

| IC | 12.7 ± 1.2 | 10.3 ± 1.0 sUc | 68.3 ± 8.2 | 40.4 ± 7.5 | 157.7 ± 27.0 Uc | 247.6 ± 36.0 | |

| IS | 11.3 ± 1.2 | 7.0 ± 1.0 | 50.0 ± 8.0 | 29.5 ± 7.2 | 211.9 ± 26.2 | 305.2 ± 34.9 | |

|

| |||||||

| Nonmaternal behaviors | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Self-groom | CC | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 45.6 ± 5.7 | 49.0 ± 6.4 | 279.8 ± 30.2 | 201.7 ± 23.7 |

| CS | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 38.0 ± 5.6 | 41.8 ± 6.3 | 331.2 ± 29.6 | 251.6 ± 23.2 | |

| UN | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 44.3 ± 5.6 | 37.4 ± 6.3 | 276.2 ± 29.6 | 192.8 ± 23.2 | |

| IC | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 46.7 ± 5.7 su | 66.9 ± 6.4SW | 288.4 ± 30.0 S | 198.7 ± 23.5 | |

| IS | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 27.9 ± 5.5 | 44.0 ± 6.2 w | 386.5 ± 29.0 | 208.9 ± 22.7 | |

| Rear-sniff | CC | 25.6 ± 1.6 | 23.6 ± 1.4 | 132.9 ± 12.0 | 137.6 ± 11.7 | 45.1 ± 6.8 | 23.7 ± 3.0 |

| CS | 25.1 ± 1.6 | 21.6 ± 1.4 | 146.8 ± 11.8 | 142.0 ± 11.5 | 37.7 ± 6.6 | 24.3 ± 2.9 | |

| UN | 24.9 ± 1.6 | 20.8 ± 1.4 | 156.3 ± 11.8 | 126.6 ± 11.5 | 40.3 ± 6.6 | 24.6 ± 2.9 | |

| IC | 24.1 ± 1.6 | 18.9 ± 1.4 | 130.8 ± 11.9 | 93.8 ± 11.6 | 34.4 ± 6.7 | 24.5 ± 3.0 | |

| IS | 24.8 ± 1.5 | 21.3 ± 1.4 | 153.1 ± 11.5 | 147.8 ± 11.2 | 29.3 ± 6.5 | 19.6 ± 2.9 | |

| Other | CC | 57.3 ± 2.4 | 53.2 ± 2.2 | 363.6 ± 18.5 | 285.3 ± 19.3 | 6.7 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 0.4 |

| CS | 56.2 ± 2.3 | 54.9 ± 2.2 | 374.4 ± 18.1 | 315.3 ± 18.9 | 3.0 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | |

| UN | 53.4 ± 2.3 | 49.8 ± 2.2 | 339.0 ± 18.1 | 285.6 ± 18.9 | 3.4 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | |

| IC | 58.4 ± 2.3 | 53.0 ± 2.2 | 382.2 ± 18.3 | 285.2 ± 19.0 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | |

| IS | 54.6 ± 2.3 | 49.4 ± 2.1 | 329.1 ± 17.7 | 301.2 ± 18.5 | 2.8 ± 1.6 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | |

Note. Means with capitalized letters differ at p ≤ 0.01 while lowercase letters differ at p ≤ 0.05. Different letters indicate differences as follows: S(s) indicates groups significantly different from respective saline control, U(u) indicate groups significantly different from UN treated dams, C(c) indicates significant difference from cocaine treated groups (CC and IC). W(w) indicates significant within group differences between days 5 and 10.

There was a significant within-group main effect of dam treatment between PPD 5 and 10 on crouch frequency, F(4, 321) = 4.77, p ≤ .01, and duration of self-groom, F(4, 321) = 2.77, p ≤ .05. Untreated and chronically treated groups crouched more often (but for shorter durations) on PPD 5 than 10, and although activity was generally constant, self-grooming was increased in intermittent groups on PPD 10 compared with 5.

PPD 15—Significant Behavioral Effects

As shown in Table 5, there were significant main effects of dam treatment on the duration, F(4, 326) = 6.64, p ≤ .01, of crouching–feeding; self-grooming, F(4, 326) = 13.49, p ≤ .01; and other, F(4, 326) = 11.00, p ≤ .01; the latency of crouching–feeding, F(4, 326) = 4.48, p ≤ .01; lick pups, F(4, 326) = 3.25, p ≤ .01; nest building, F(4, 326) = 6.74, p ≤ .01; and group pups, F(4, 326) = 7.42, p ≤ .01; and the frequency of nest building, F(4, 326) = 3.48, p ≤ .01; group pups, F(4, 326) = 5.60, p ≤ .01; rear–sniff, F(4, 326) = 6.22, p ≤ .01; and other, F(4, 326) = 5.47, p ≤ .01. Generally, all aspects of pup-directed and non-pup-directed behaviors were interrupted (increased activity, decreased maternal behavior) by IC treatment just prior to testing.

Table 5.

Original Dams PPD 15 Maternal Behavior: Dam Treatment Effects

| Pup-directed maternal behaviors | Dam treatment

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CS | UN | IC | IS | ||

| Crouch | Frequency | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.4 |

| Duration (s) | 352.5 ± 25.8 | 305.9 ± 25.4 | 324.3 ± 25.2 | 188.1 ± 25.2 SUC | 331.0 ± 24.2 | |

| Latency (s) | 368.4 ± 27.3 | 403.0 ± 27.0 | 389.9 ± 26.8 | 507.9 ± 26.7 SUC | 378.3 ± 25.6 | |

| Lick pups | Frequency | 10.1 ± 0.9 | 9.5 ± 0.9 | 9.2 ± 0.9 | 8.6 ± 0.9 | 10.1 ± 0.8 |

| Duration (s) | 88.0 ± 10.3 | 82.4 ± 10.2 | 105.5 ± 10.1 | 81.4 ± 10.1 | 85.8 ± 9.7 | |

| Latency (s) | 75.6 ± 23.4 | 93.4 ± 23.1 | 115.2 ± 22.9 | 177.1 ± 22.8 SUC | 81.9 ± 21.9 | |

| Nest-build | Frequency | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.6 SUc | 4.0 ± 0.6 |

| Duration (s) | 20.6 ± 4.7 | 21.1 ± 4.6 | 22.2 ± 4.6 | 6.7 ± 4.6 | 23.3 ± 4.4 | |

| Latency (s) | 474.6 ± 43.2 | 480.5 ± 42.6 | 416.3 ± 42.3 | 680.2 ± 42.2 SUC | 414.5 ± 40.5 | |

| Group-pups | Frequency | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.5 SUC | 3.8 ± 0.5 |

| Latency (s) | 334.1 ± 50.7 | 311.0 ± 50.0 | 289.6 ± 49.6 | 614.4 ± 49.5 SUC | 326.0 ± 47.5 | |

|

| ||||||

| Nonmaternal behaviors | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Self-groom | Frequency | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 10.8 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.5 |

| Duration (s) | 45.2 ± 6.6 | 47.7 ± 6.5 | 39.7 ± 6.5 | 97.7 ± 6.5 SUC | 48.0 ± 6.2 | |

| Latency (s) | 209.9 ± 20.6 | 201.7 ± 20.3 | 172.6 ± 20.2 | 98.6 ± 20.1 | 186.0 ± 19.3 | |

| Rear-sniff | Frequency | 21.0 ± 1.8 | 21.4 ± 1.8 | 21.0 ± 1.8 | 30.3 ± 1.8 SUC | 19.4 ± 1.7 |

| Duration (s) | 125.7 ± 11.8 | 141.7 ± 11.6 | 119.8 ± 11.5 | 140.1 ± 11.5 | 127.1 ± 11.0 | |

| Latency (s) | 11.7 ± 1.5 | 12.5 ± 1.5 | 10.3 ± 1.5 | 12.0 ± 1.5 | 12.5 ± 1.4 | |

| Other | Frequency | 42.5 ± 2.4 | 42.4 ± 2.3 | 43.5 ± 2.3 | 54.5 ± 2.3 SUC | 41.6 ± 2.2 |

| Duration (s) | 215.5 ± 15.8 | 232.3 ± 15.6 | 245.3 ± 15.5 | 339.4 ± 15.4 SUC | 219.44 ± 14.8 | |

| Latency (s) | 2.7 ± 6.0 | 16.3 ± 5.9 | 2.5 ± 4.9 | 2.8 ± 5.8 | 1.9 ± 5.6 | |

Note. Means with capitalized letters differ at p ≤ 0.01 while lowercase letters differ at p ≤ 0.05. Different letters indicate differences as follows: S(s) indicates groups significantly different from respective saline control, U(u) indicate groups significantly different from UN treated dams, C(c) indicates significant difference from cocaine treated groups (CC and IC).

Original Dams: Litter Prenatal Exposure Effects PPD 1

The prenatal exposure condition of the litter significantly affected the duration of nest building by all dams, F(4, 333) = 2.52, p ≤ . 04. Dams that reared pups prenatally exposed to CC and IC spent less and more time, respectively, nest building compared with dams that reared pups prenatally exposed to CS (p ≤ .02) and IS (p ≤ .05). Dams that reared CC exposed pups also had a shorter duration of nest building than dams rearing IC exposed pups (p ≤ .05). Table 6 indicates the mean and standard error of the mean for behaviors on PPD 1 of all dams based on the prenatal exposure of the litter they reared, regardless of their own drug treatment. There were also many strong trends that persisted over the entire testing period (PPD 1–15), indicating that mainly CC, and to a lesser degree IC exposed pups, received less overall maternal care (less or later crouching, licking, touching, more resting away from pups) than offspring from other prenatal exposure conditions.

Table 6.

Original Dams PPD 1 Maternal Behavior: Litter Prenatal Exposure Effects

| Pup-directed maternal behaviors | Litter prenatal exposure condition

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CS | IC | IS | UN | ||

| Crouch | Frequency | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 6.1 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.6 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 6.6 ± 0.6 |

| Duration (s) | 646.0 ± 65.3 | 589.0 ± 64.3 | 803.9 ± 64.6 | 707.6 ± 65.2 | 715.1 ± 59.2 | |

| Latency (s) | 472.5 ± 76.6 | 524.4 ± 77.3 | 492.6 ± 77.5 | 699.2 ± 75.7 | 566.0 ± 70.3 | |

| Lick pups | Frequency | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 5.1 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 0.6 |

| Duration (s) | 58.0 ± 10.8 | 65.1 ± 10.5 | 42.8 ± 10.7 | 61.1 ± 10.7 | 60.7 ± 9.8 | |

| Latency (s) | 682.2 ± 89.9 | 663.4 ± 87.9 | 637.5 ± 88.9 | 582.5 ± 88.8 | 638.8 ± 81.5 | |

| Touch/sniff pups | Frequency | 22.4 ± 1.3 | 23.9 ± 1.2 | 21.3 ± 1.3 | 21.3 ± 1.2 | 24.4 ± 1.2 |

| Duration (s) | 110.9 ± 9.7 | 136.8 ± 9.5 | 107.7 ± 9.6 | 109.5 ± 9.5 | 130.1 ± 8.8 | |

| Latency (s) | 32.9 ± 4.5 | 19.6 ± 7.3 | 39.3 ± 7.4 | 22.5 ± 7.3 | 31.1 ± 6.8 | |

| Nest-build | Frequency | 7.5 ± 1.7 | 12.7 ± 1.7 | 12.5 ± 1.7 | 10.2 ± 1.7 | 12.0 ± 1.6 |

| Duration (s) | 56.8 ± 15.2 s | 117.1 ± 14.8 | 105.5 ± 15.0 sc | 76.0 ± 15.0 | 89.8 ± 13.7 | |

| Latency (s) | 613.7 ± 81.0 | 434.5 ± 79.2 | 408.9 ± 80.1 | 532.2 ± 80.0 | 556.4 ± 73.5 | |

|

| ||||||

| Nonmaternal behaviors | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Rest off/lay on | Frequency | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.4 |

| Duration (s) | 256.8 ± 35.5 | 239.9 ± 34.7 | 180.9 ± 35 | 165.2 ± 35.5 | 240.1 ± 32.2 | |

| Latency (s) | 656.1 ± 86.3 | 999.4 ± 84.4 | 880.9 ± 85.4 | 805.6 ± 86.1 | 778.4 ± 78.3 | |

Note. Means with capitalized letters differ at p ≤ 0.01 while lowercase letters differ at p ≤ 0.05. Different letters indicate differences as follows: S(s) indicates groups significantly different from respective saline control, U(u) indicate groups significantly different from UN treated dams, C(c) indicates significant difference from cocaine treated groups (CC and IC).

Original Dams: Dam Treatment and Litter Prenatal Exposure Interactions—Significant Behavioral Effects

PPD 1

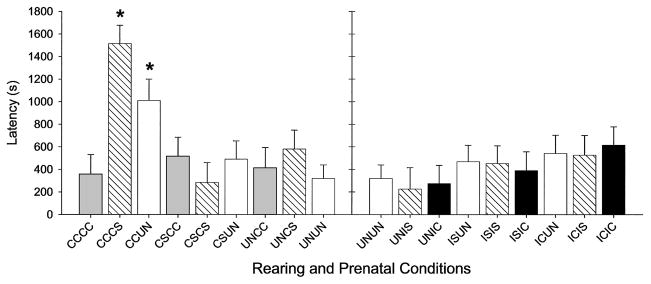

There was a significant interaction between dam treatment and litter exposure on the latency to crouch, F(16, 332) = 1.86, p ≤ .02. As shown in Figure 1, CC treated dams rearing CS or UN exposed pups crouched later than all other chronically treated dams rearing pups from any prenatal exposure group (p ≤ .05), and CCCS dams crouched later than all IC treated dams rearing pups from any prenatal exposure condition (p ≤ .05).

Figure 1.

Least squares means (LSM; ± SEM) of latency to crouch in original dams on Postpartum Day 1. Dam treatment and litter prenatal conditions are described on the x-axis, with the first two letters of each group representing the drug treatment condition and the second two letters of each group representing the prenatal exposure of the dams’ litter. Group designations are as follows: CC = chronic cocaine; CS = chronic saline; IC = intermittent cocaine; IS = intermittent saline; UN = no treatment. Asterisks indicate that dams treated with CC crouched over CS or UN exposed pups later in the session than any other group (p ≤ .05).

PPD 5 to 10

There was a significant interaction of dam treatment and prenatal litter exposure on within-group lick pup latency, F(16, 321) = 2.27, p ≤ .01. All groups licked later on PPD 5 than 10 except CCCS, UNCC, UNCS, ICIS, and UNIC treatment groups (p ≤ .05).

PPD 15

There were no significant interaction effects on pup-directed maternal behaviors on PPD 15. Differences between treatment groups on activity and non-pup-directed behaviors are reflective of dam treatment effects.

FGDs: Gestational Variables

There was a significant effect of rearing condition on gestational weight gain only, F(4, 261) = 3.162, p ≤ .02; see Table 7). IC reared dams gained the most weight over gestation.

Table 7.

FGD Maternal Gestation and Litter Data Based on Rearing Condition

| Dam rearing condition | Number of dams | Gestational weight gain (g) | Whole litter weight (g) | Number of pups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 48 | 141.1 ± 5.2 | 95.3 ± 2.6 | 14.5 ± 0.4 |

| CS | 57 | 134.5 ± 4.7 | 87.2 ± 2.4 | 13.5 ± 0.4 |

| UN | 67 | 145.5 ± 4.5 | 91.5 ± 2.3 | 14.0 ± 0.4 |

| IC | 57 | 157.7 ± 4.8 Sc | 93.9 ± 2.4 | 14.6 ± 0.4 |

| IS | 64 | 146.6 ± 4.5 | 93.4 ± 2.3 | 14.8 ± 0.4 |

Note. Uppercase S(s) indicates significant difference from chronic saline treated group at the P ≤ 0.01 level. Lowercase C(c) indicates significant difference from chronic cocaine group (CC) at the P ≤ 0.05 level.

FGDs: Rearing Dam Treatment Effects PPD 1—Significant Behavioral Effects

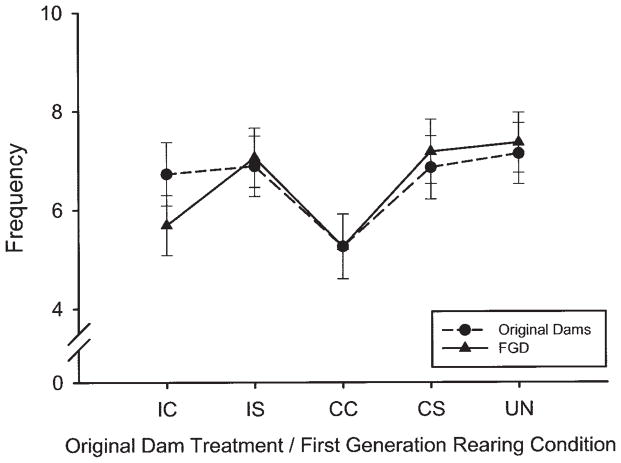

There was a significant main effect of rearing condition on the frequency of other behaviors, F(4, 262) = 2.72, p ≤ .03, as shown in Table 8. FGDs reared by CC treated dams performed other behaviors less frequently than CS reared dams (p ≤ .01) and had an almost significantly lower frequency of crouching, F(4, 260) = 2.32, p = .06, than UN or CS reared dams (see Figure 2 and Table 8).

Table 8.

First Generation Dams PPD 1 Maternal Behavior: Rearing Dam Treatment Effects and Prenatal Exposure Effects

| Pup-directed maternal behaviors | Rearing dam treatment

|

Prenatal exposure condition

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CS | UN | IC | IS | CC | CS | UN | IC | IS | ||

| Crouch | Frequency | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 0.6 | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.6 |

| Duration (s) | 835.1 ± 64.2 | 765.3 ± 63.4 | 764.3 ± 60.4 | 798.1 ± 60.9 | 797.2 ± 59.3 | 739.2 ± 64.0 | 853.0 ± 63.4 | 832.8 ± 55.7 | 726.4 ± 62.3 | 808.5 ± 62.1 | |

| Latency (s) | 594.2 ± 64.3 | 492.8 ± 63.5 | 487.0 ± 60.4 | 625.3 ± 60.4 | 428.2 ± 59.3 | 499.0 ± 63.6 | 442.5 ± 63.5 | 624.8 ± 55.8 | 537.2 ± 62.3 | 523.9 ± 62.2 | |

| Touch/sniff pups | Frequency | 22.4 ± 1.3 | 24.8 ± 1.3 | 23.4 ± 1.2 | 22.4 ± 1.3 | 22.1 ± 1.2 | 21.6 ± 1.3 | 21.8 ± 1.3 | 22.9 ± 1.2 | 24.6 ± 1.3 | 24.3 ± 1.3 |

| Duration (s) | 155.1 ± 11.0 | 156.5 ± 10.8 | 154.3 ± 10.3 | 149.0 ± 10.4 | 133.8 ± 10.2 | 138.0 ± 10.8 | 152.7 ± 10.9 | 141.1 ± 9.5 | 167.7 ± 10.7 | 149.1 ± 10.7 | |

| Latency (s) | 39.0 ± 11.6 | 19.4 ± 11.4 | 13.8 ± 10.9 | 47.4 ± 10.9 | 27.7 ± 10.7 | 21.9 ± 11.4 | 44.8 ± 11.5 | 35.5 ± 10.1 | 22.9 ± 11.3 | 22.3 ± 11.3 | |

| Retrieve 8 | Latency (s) | 160.7 ± 51.6 | 231.7 ± 50.5 | 222.8 ± 48.4 | 220.8 ± 48.5 | 215.6 ± 47.6 | 356.0 ± 50.5 SC | 172.9 ± 50.9 | 238.7 ± 44.7 | 137.3 ± 50.0 | 146.8 ± 49.9 |

| Lick pups | Frequency | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.6 |

| Duration (s) | 73.8 ± 14.9 | 77.9 ± 14.5 | 73.8 ± 13.9 | 92.4 ± 14.0 | 68.1 ± 13.7 | 79.8 ± 14.6 | 59.6 ± 14.7 | 82.6 ± 12.9 | 86.1 ± 14.4 | 77.9 ± 14.4 | |

| Latency (s) | 663.6 ± 90.9 | 613.1 ± 88.9 | 526.8 ± 85.2 | 720.9 ± 85.5 | 854.9 ± 83.9 | 666.8 ± 89.1 | 667.7 ± 89.8 | 753.6 ± 78.7 | 632.9 ± 88.2 | 658.3 ± 88.0 | |

| Nest-build | Frequency | 7.3 ± 1.4 | 10.9 ± 1.4 | 9.0 ± 1.3 | 6.9 ± 1.3 | 6.1 ± 1.3 | 7.3 ± 1.4 | 7.6 ± 1.4 | 9.2 ± 1.2 | 9.4 ± 1.4 | 6.7 ± 1.4 |

| Duration (s) | 94.5 ± 16.7 | 105.4 ± 16.3 | 96.8 ± 15.6 | 66.3 ± 15.7 | 75.0 ± 15.4 | 65.6 ± 16.3 | 80.5 ± 16.5 | 113.1 ± 14.4 | 95.4 ± 16.2 | 83.4 ± 16.1 | |

| Latency (s) | 613.1 ± 91.0 | 426.9 ± 89.0 | 407.2 ± 85.3 | 430.6 ± 84.0 | 574.6 ± 84.0 | 444.0 ± 89.2 | 403.4 ± 89.9 | 531.4 ± 78.8 | 499.4 ± 88.3 | 574.0 ± 88.0 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Nonmaternal behaviors | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Rest off/lay on | Frequency | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 |

| Duration (s) | 171.2 ± 29.6 | 108.5 ± 28.8 | 101.2 ± 27.7 | 215.2 ± 27.9 | 106.7 ± 27.4 | 215.4 ± 28.8 SUc | 84.0 ± 29.3 | 96.3 ± 25.6 | 133.7 ± 28.8 | 83.5 ± 28.7 | |

| Latency (s) | 1013.5 ± 100.6 | 964.4 ± 97.6 | 1218.2 ± 94.1 | 1017.8 ± 94.6 | 1188.8 ± 92.9 | 1036.8 ± 97.8 | 1098.6 ± 99.4 | 1031.1 ± 86.9 | 983.4 ± 97.6 | 1252.7 ± 97.3 | |

| Self-groom1 | Frequency | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 0.6 |

| Duration (s) | 71.7 ± 11.3 | 78.3 ± 11.0 | 98.5 ± 10.6 | 67.8 ± 10.6 | 86.0 ± 10.4 | 88.2 ± 11.0 | 77.2 ± 11.1 | 80.7 ± 9.8 | 73.2 ± 10.9 | 82.9 ± 10.9 | |

| Latency (s) | 524.9 ± 52.9 | 436.7 ± 51.7 | 464.7 ± 49.6 | 449.1 ± 49.8 | 440.3 ± 48.8 | 433.2 ± 51.8 | 461.0 ± 52.2 | 439.3 ± 45.8 | 560.6 ± 51.3 | 421.7 ± 51.2 | |

| Rear-sniff | Frequency | 8.4 ± 1.5 | 12.5 ± 1.4 | 11.4 ± 1.4 | 10.7 ± 1.4 | 10.8 ± 1.3 | 10.8 ± 1.4 | 9.9 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ± 1.3 | 10.3 ± 1.4 | 11.6 ± 1.4 |

| Duration (s) | 40.6 ± 9.8 | 59.6 ± 9.6 | 59.9 ± 9.2 | 50.8 ± 9.2 | 54.1 ± 9.0 | 54.2 ± 9.6 | 44.6 ± 9.7 | 62.6 ± 8.5 | 47.5 ± 9.5 | 56.1 ± 9.5 | |

| Latency (s) | 123.5 ± 34.1 | 59.8 ± 33.4 | 100.3 ± 32.0 | 182.0 ± 32.1 | 83.6 ± 31.5 | 58.0 ± 33.5 | 168.8 ± 33.7 | 114.0 ± 29.6 | 110.3 ± 33.1 | 98.2 ± 33.0 | |

| Other | Frequency | 35.9 ± 3.1 Su | 48.7 ± 3.0 | 45.3 ± 2.9 | 39.3 ± 2.9 | 41.6 ± 2.9 | 41.3 ± 3.1 | 41.6 ± 3.1 | 42.3 ± 2.7 | 41.9 ± 3.0 | 43.8 ± 3.0 |

| Duration (s) | 333.5 ± 40.1 | 415.1 ± 39.2 | 448.4 ± 37.6 | 416.0 ± 37.7 | 429.0 ± 37.0 | 413.1 ± 39.3 | 417.1 ± 39.6 | 418.9 ± 34.7 | 379.1 ± 38.9 | 413.8 ± 38.8 | |

| Latency (s) | 14.3 ± 4.1 | 2.9 ± 4.0 | 4.3 ± 3.8 | 7.3 ± 3.8 | 5.3 ± 7.7 | 3.6 ± 4.0 | 6.0 ± 4.0 | 14.3 ± 3.5 | 6.9 ± 3.9 | 3.3 ± 3.9 | |

Note. Means with capitalized subscripts differ at p ≤ 0.01 while lowercase subscripts differ at p ≤ 0.05. Different letters indicate differences as follows: S(s) indicates groups significantly different from respective saline control, C(c) indicates significant difference from cocaine groups, while U(u) indicate groups significantly different from UN-treated dams.

Figure 2.

Least squares means (± SEM) of the frequency of crouching for original and first-generation dams (FGDs) on Postpartum Day 1. Designations on the x-axis indicate drug treatment of original dams and, consequently, the rearing dams’ condition for FGDs. Treatment included chronic cocaine (CC), chronic saline (CS), intermittent cocaine (IC), intermittent saline (IS), or no treatment (UN) throughout gestation (Gestation Days 1–20). Solid lines with solid circles represent original dam frequency, whereas gray lines with open triangles represent FGDs. CC treated dams and FGDs reared by CC treated dams both crouch less frequently (p ≤ .06, ns) than UN treated dams and FGDs reared by UN dams.

FGDs: Prenatal Exposure Effects PPD 1—Significant Behavioral Effects

As shown in Table 8, there were significant effects of prenatal exposure on the latency to retrieve all 8 pups, F(4, 262) = 3.25, p ≤ .01, and the duration of rest away–lie on pups, F(4, 264) = 2.79, p ≤ .01. CC exposed dams took longer to retrieve all 8 pups than CS, IC (p ≤ .01, both), and UN (ns) exposed FGDs and spent more time resting away from pups or lying flat on top of pups than did CS, UN (p ≤ .01, both), or IC (p ≤ .04) exposed dams.

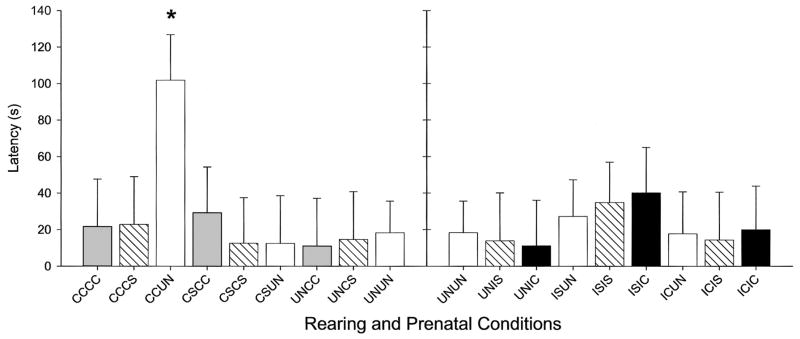

FGDs: Rearing Dam Treatment and Prenatal Exposure Interactions PPD 1—Significant Behavioral Effects

There was a significant interaction effect (see Figure 3) on the latency to touch–sniff pups, F(16, 262) = 1.86, p ≤ .02. FGDs with no prenatal drug exposure that were reared by CC treated dams (CCUN) touched pups later (p ≤ .05) than other dams reared by CS or UN treated dams with pups from other prenatal exposure conditions and than any other CC or IC reared dams from any relevant prenatal exposure condition (p ≤ .05).

Figure 3.

Least squares means (LSM; ± SEM) of latency to touch–sniff in first-generation dams (FGDs) on Postpartum Day 1. Rearing and prenatal conditions are described on the x-axis, with the first two letters of each group representing the rearing dam condition and the second two letters of each group representing the prenatal exposure condition of the FGDs. Group designations are as follows: CC = chronic cocaine; CS = chronic saline; IC = intermittent cocaine; IS = intermittent saline; UN = no treatment. The asterisk indicates that the CC reared dams, prenatally exposed to no drug treatment (CCUN), touched their natural untreated pups later in the session than any other group (p ≤ .05).

Original Dams: Oxytocin Levels PPD 22

There were no significant effects of dam treatment on oxytocin levels in the amygdala, MPOA, VTA, or hippocampus, nor were there significant effects of prenatal pup exposure condition on the oxytocin levels in amygdala, VTA, or hippocampus. Of interest, IC and CC treated dams had trends of less oxytocin in the MPOA (p ≤ .15) than UN treated dams, and all dams rearing UN pups had more oxytocin in the MPOA (p ≤ .16).

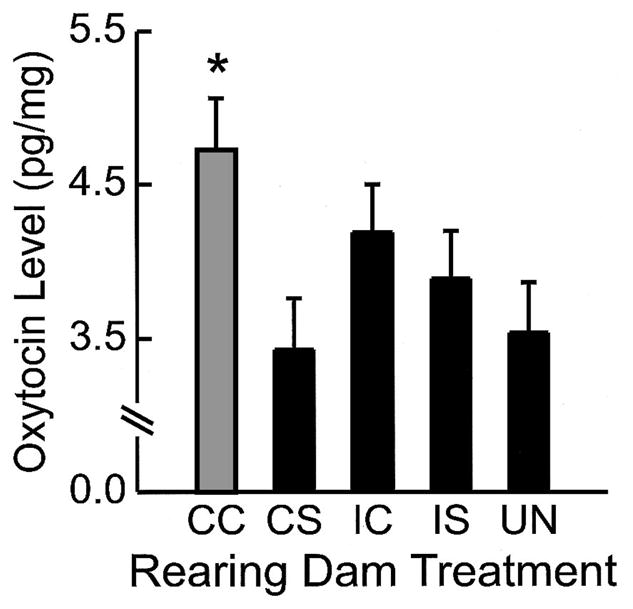

FGDs: Oxytocin Levels PPD 2

There were significantly higher oxytocin levels (pg/mg) in the MPOA of FGDs reared by CC treated mothers, F(4, 16) = 2.50, p ≤ .04, than offspring reared by UN and CS (p ≤ .01) treated dams (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Least squares means (± SEM) of oxytocin levels in the medial preoptic area in first-generation dams (FGDs) based on rearing condition on Postpartum Day 2. Rearing dam treatment of FGDs is indicated on the x-axis. The asterisk indicates that FGDs, regardless of their prenatal exposure condition, that were reared by CC treated dams had higher oxytocin levels in the MPOA than any FGDs reared by CS treated dams (p ≤ .01).

Discussion

The findings of this study support our first hypotheses, as CC and IC drug treatment both disrupted the onset of maternal behavior, with CC treatment having a stronger and even more widespread effect than we expected compared with IC treatment, which diminished over the postpartum period, except when IC dams had cocaine in their system at the time of testing (PPD 15). This was supported by the data as well, because the most robust effects on pup-directed behavior (other than IC on PPD 15) were on PPD 1, whereas later effects were restricted to primarily activity-associated behaviors. The disruptive effects of CC treatment on PPD 1, regardless of litter prenatal exposure, are similar to those previously reported with CC treated dams rearing only surrogate offspring (Johns, Noonan, et al., 1994). Delays in nest building, as we measured it, were also previously reported for CC treated dams (Johns, Noonan, et al., 1994) on PPD 1. In the present study, the opposite effect was found. Measurement of nest quality might have been more helpful in interpreting whether longer periods of nest building on PPD 1 were indicative of increased general activity or more applied maternal behavior. In addition to decreased crouching, which we consistently find in CC treated dams, there were also nonsignificant trends for them to touch pups later, to rest away from or lie flat on pups longer, and to lick pups later than other dams, indicating a general disruption of pup-directed behavior on PPD 1 with primarily trends continuing into PPD 5. The increase in activity of CC treated dams on PPD 1 in this study has not been previously reported, and they did not have cocaine in their system at testing.

The IC treated dams had fewer effects overall than expected, until the complete disruption of maternal behavior on PPD 15, similar to that shown when acutely treated rat dams have cocaine present in their system during testing. IC effects on maternal behavior on PPD 15 were greater than those seen following a single acute dose of cocaine, suggesting that continuous IC treatment across gestation and the postpartum period did increase the magnitude of impairment (Johns, Noonan, et al., 1994; Vernotica et al., 1996; Zimmerberg & Gray, 1992). IC treated dams also exhibited increased activity across the postpartum period unlike other dams.

In addition to the expected main effects of drug treatment on maternal behavior, there were effects and consistent trends across the postpartum period as a function of rearing litter prenatal exposure, though yearly variability likely precluded some effects from being statistically significant over the 4-year period. CC exposed pups were expected to produce the most significant litter effects, particularly when reared by cocaine treated dams, but of interest and importance, we found a pattern of differential treatment of pups prenatally exposed to cocaine by all dams regardless of their treatment condition. Consistent trends, some quite strong (p ≤ .06–.07) were found, indicating impaired or delayed nesting; less crouching, licking, touching of pups; and more time spent resting away or laying flat on pups. In our subjects, the behavior of laying flat on the pups did not appear to stimulate nursing, although others may disagree (Stern & Johnson, 1989).

Rat pups prenatally exposed to cocaine at different ages differ in their stress responsivity, response to tactile stimuli (Johns, Knapp, & Noonan, 1994), and ability to elicit play solicitations from an untreated conspecific (Johns & Noonan, 1995; Overstreet et al., 2000); have play deficits (Wood, Bannoura, & Johanson, 1994; Wood, Molina, Wagner, & Spear, 1995); and exhibit abnormal social–aggressive behavior when older (Johns, Knapp, & Noonan, 1994; Johns, Means, et al., 1994; Overstreet et al., 2000). These data, taken together, suggest that behavior and physical attributes of drug exposed offspring may make them more vulnerable to neglect or even abusive behavior. Preliminary data in humans suggest that premature babies or babies with low birth weight are physically unattractive and emit disturbing high-pitched, arrhythmic cries, leaving them more susceptible to abuse and neglect (Belsky, 1993; Brunk & Henggeler, 1984). We regard this issue of characteristics of offspring that may lead to poorer social outcomes as very important.

Similarly to what has been reported in CC treated dams rearing surrogate pups, in this study, CC treated dams rearing CS or UN exposed pups began crouching later than other dams (Johns, Noonan, et al., 1994; Johns, Means, et al., 1994; Johns, Noonan, et al., 1998; Kinsley et al., 1994; Vernotica et al., 1996). A previous study reported that maternal behavior (pup retrieval, nesting behavior, or time with pups) of CC treated dams did not differ between groups rearing their own biological offspring or fostered offspring when they were tested for established maternal behavior (Heyser et al., 1992). The main effects of drug treatment reported here, regardless of prenatal exposure of the litter, support these findings, although again, all dams were less attentive to the CC exposed offspring overall.

The CS and IS control groups were for the most part similar to UN dams, although there were, as expected, some behavioral differences, particularly in the CS dams. Behavioral differences between saline treated and UN dams probably result both from the pair feeding procedure used to control for food intake and/or the stress response of the mother to either injections or food restriction as previously suggested (Lubin, Meter, Walker, & Johns, 2001; Spear et al., 2002; Tonkiss, Shumsky, Shultz, Almeida, & Galler, 1995). These differences, although often not significant, suggest that changes in behavior probably result both from the environmental stress (food, injections, litter) and direct effects of cocaine.

We hypothesized that there would be intergenerational effects on maternal behavior in the next-generation dams, largely resulting from prenatal exposure to cocaine but also influenced by the treatment of dams who reared them. Our hypotheses were supported in that we did find both rearing and prenatal effects on the onset of maternal behavior, with more significant effects in the FGDs prenatally exposed to CC. It must be noted that IC reared FGDs were exposed to cocaine in their dam’s milk on the days IC dams were treated, and the biological or metabolic effects of postpartum cocaine exposure in these dams may have had their own effects.

Prenatal exposure effects of cocaine in FGDs were different from effects of rearing condition in several ways. Retrieval and time spent away from pups were altered in the CC exposed dams, and both IC and CC exposed dams had shorter (ns) durations of crouching, touched pups less, nest built less, and were more active than other FGDs. These effects are somewhat reminiscent of the CC treated dams in terms of activity and crouching, but to a much less extensive degree. Alternatively, rearing by CC treated dams disrupted frequency but not duration of crouching in FGDs, regardless of their prenatal exposure condition, and decreased general activity. They also exhibited trends to touch, crouch, and lick pups later and rest away from pups more than other FGDs from different rearing conditions. Figure 2 illustrates the striking similarity of crouch frequency between FGDs and their rearing dam regardless of prenatal exposure, except for IC reared dams, perhaps because of postpartum exposure to cocaine in the milk, which is an interesting possibility. Again, the effects of both prenatal and rearing condition in FGDs on crouching emphasize the consistent effects of cocaine on different aspects of nursing in both generations.

We thought that interactions in FGDs would be most evident in CCCC or CCIC dams; however, the CCUN dams touched their own natural pups later than CS or UN reared dams, suggesting a stronger rearing effect on this behavior than the prenatal exposure effect.

With regard to oxytocin system dynamics, we predicted that if IC or CC treatment in original parent dams resulted in long-term changes in maternal behavior over the postpartum period, oxytocin levels in the MPOA might still be compromised to a degree, given the strong relationship between oxytocin levels, maternal behavior, and social behavior. Although oxytocin is not thought to play an essential role in maintenance of maternal behavior, it could still impact pup-directed motivational behavior. As there were mainly diminishing trends in maternal behavior after PPD 5 in CC and IC treated dams (except IC dams on PPD 15), so there was a nonsignificant decrease in oxytocin in the MPOA as far out as PPD 22, one day following weaning. More interesting, perhaps, is the trend for all dams that reared UN exposed pups to have slightly more oxytocin in their MPOA on PPD 22. These findings leave open the question of a continuing, if less important, role of oxytocin in sustained maternal behavior, which may be affected by quality of maternal pup interactions.

Our finding of higher levels of oxytocin in the MPOA of CC and to a lesser extent IC reared next-generation dams was not predicted, as we expected that disrupted maternal behavior in these dams might be correlated with lower levels of oxytocin in this region as was previously seen in CC treated dams. In trying to reconcile these findings, we examined maternal separation studies (Boccia & Pedersen, 2001; Champagne, Diorio, Sharma, & Meaney, 2001; Francis et al., 1999; Rees & Fleming, 2001), particularly those that have found oxytocin system dynamics altered in offspring based on the licking and crouching behavior of their rearing dams (Pedersen & Boccia, 2002). While CC reared FGDs crouched less frequently, crouch duration, which is often measured in separation studies, was not altered in this group, and the specific subgroups with the CC reared FGDs that displayed longer crouch durations actually had higher oxytocin levels, which could be driving the overall differences. Likewise, licking, though not significantly altered in CC treated dams as it is in dams with cocaine in their system at the time of testing (PPD 15), has also been associated with higher levels of oxytocin. In the current study, licking was also increased in some of the IC reared subgroups that had higher oxytocin levels; thus, the IC and CC reared FGDs that had longer durations of licking and crouching, respectively, actually had higher levels of oxytocin, which is not inconsistent with the separation literature. It is possible that oxytocin system changes are closely tied to specific aspects of particular behaviors (duration, not frequency) and not others.

In addition, this and other recent studies lead us to speculate that we could be seeing an oxytocin rebound response in CC reared offspring associated with pup related stimuli. Although there are few significant effects on maternal behavior related to rearing by cocaine treated dams, it is possible that the oxytocin system in these dams, which may be compromised, is perhaps overcompensating in response to pups. Because reduced oxytocin receptor levels in CC reared FGDs would be predicted by the Pedersen model (Boccia & Pedersen, 2001), it will be interesting to see how our future findings fit with this model.

Any study involving the complex design of the present report necessarily has limitations. The potential problems of cross fostering (Francis et al., 1999) were hopefully offset in the present study by ensuring that dams received litters from every other dam, at least matching for fostering effects. It would also have been nice to avoid yearly variability by doing the study in a shorter time period, but that was practically impossible. Although the FGDs were only tested for onset of maternal behavior, had we continued to examine mother–pup interactions over the PP period we might have found additional interesting results—but again, the magnitude of the project was such that this could not be done as additional tests were done on other offspring.

Finally, several conclusions may be drawn from this study including the following: (a) that chronic cocaine treatment and intermittent cocaine treatment both alter primarily the onset of maternal behavior in rat dams (when cocaine is not in their system) and that chronic treatment generally has the more disruptive effect initially, diminishing across the postpartum period, but when cocaine is in the system, maternal behavior is, as expected, severely impaired regardless of litter prenatal exposure condition; (b) that there are intergenerational effects of cocaine on the onset of maternal behavior in FGDs attributable in some instances to prenatal exposure or to rearing condition and/or the interaction of these two factors, but all to a much lesser degree than that seen in their cocaine treated dams; (c) that generally, prenatal exposure to CC increases the chances that a litter will be treated differentially; and (d) that oxytocin is increased rather than decreased in the MPOA of CC reared FGDs, in an opposite manner as found in their CC treated dams.

The fact that despite the cocaine treatments, the drug treated dams performed in a manner that was somewhat adequate, if impaired, maternal behavior with diminishing effects highlights the robust nature of maternal behavior in rats. Yet, although the rearing effects were not particularly robust effects, they may likely impact other types of offspring behavior (other than maternal), particularly in combination with effects of prenatal exposure to cocaine at different developmental time points. Given the relatively milder effects in the rat dams compared with effects reported in the human population, these findings indicate that in humans, factors such as polydrug abuse and environment probably play a larger role in cocaine’s effects and that future animal studies focusing on the interaction of stress, environment, and relevant polydrug abuse models may be very informative. One important common finding in this and other intergenerational studies (cocaine, maternal separation) is that there is some transfer of behavior resulting from altered maternal care, which manifests itself in the next generation, suggesting a decreased flexibility in behavior, whether the result of the stress of separation or neglect induced by drugs, that impacts future generations. Given the potential impact of these findings, future studies in our lab will focus on questions of specific characteristics of offspring that may enhance neglect, polydrug models, and vulnerability of next-generation offspring to drug abuse.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant DA13362-01 and the NIH Federal Child Neglect Consortium. We want to acknowledge the assistance of Linda P. Spear as a consultant for this project. We also want to acknowledge all the premed, biology, and psychology honors students and summer students (especially Brandon Waters, Raeesa Mirza, and Trevor Rodrigues) from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and surrounding universities, whose cumulative efforts helped make the completion of this project possible.

Contributor Information

Josephine M. Johns, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Deborah L. Elliott, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Vivian E. Hofler, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Paul W. Joyner, College of Medicine, University of South Alabama

Matthew S. McMurray, Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Thomas M. Jarrett, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Amber M. Haslup, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Christopher L. Middleton, Human Brain Laboratory, Medical College of Georgia

Jay C. Elliott, Department of Neurosciences, Medical University of South Carolina at Charleston

Cheryl H. Walker, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

References

- Bauman PS, Dougherty FE. Drug-addicted mothers’ parenting and their children’s development. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1983;18:291–302. doi: 10.3109/10826088309039348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays J. Substance abuse and child abuse: Impact of addiction on the child. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 1990;37:881–904. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Etiology of child maltreatment: A developmental-ecological analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:413–434. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccia ML, Pedersen CA. Brief vs. long maternal separations in infancy: Contrasting relationships with adult maternal behavior and lactation levels of aggression and anxiety. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26:657–672. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk MA, Henggeler SW. Child influences on adult controls: An experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:1074–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Burns K, Chethik L, Burns WJ, Clark R. Dyadic disturbances in cocaine-abusing mothers and their infants. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1991;47:316–319. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199103)47:2<316::aid-jclp2270470220>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F, Diorio J, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Naturally occurring variations in maternal behavior in the rat are associated with differences in estrogen-inducible central oxytocin receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:12736–12741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221224598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasnoff IJ, Anson A, Hatcher R, Stenson H, Iaukea K, Randolph LA. Prenatal exposure to cocaine and other drugs: Outcome at four to six years. In: Harvey JA, Kosofsky BE, editors. Cocaine: Effects on the developing brain. Vol. 846. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences; 1998. pp. 314–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Jacobvitz D, Papatola K. Intergenerational continuity of abuse. In: Gelles R, Lancaster J, editors. Child abuse and neglect: Biosocial dimensions. Chicago: Aldine Publishing; 1987. pp. 255–276. [Google Scholar]

- Francis D, Diorio J, Liu D, Meaney MJ. Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behavior and stress responses in the rat. Science. 1999 November 5;286:1155–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs AR. The role of oxytocin in parturition. In: Martini L, James VHT, editors. Current topics in experimental endocrinology, Vol. 4: The endocrinology of pregnancy and parturition. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 231–265. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley TL, Halle TG, Drasin RE, Thomas NG. Children of addicted mothers: Effects of the “crack epidemic” on the caregiving environment and the development of preschoolers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65:364–379. doi: 10.1037/h0079693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyser CJ, Molina VA, Spear LP. A fostering study of the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure: I. Maternal behaviors. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1992;14:415–421. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(92)90052-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Beckwith L, Espinosa M, Tyler R. Development of infants born to cocaine-abusing women: Biologic/maternal influences. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1995;17:403–411. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(94)00077-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter RS, Kilstrom N, Kraybill EN, Loda F. Antecedents of child abuse and neglect in premature infants: A prospective study in a newborn intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 1978;61:629–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Faggin BM, Noonan LR, Li L, Zimmerman LI, Pedersen CA. Chronic cocaine treatment decreases oxytocin levels in the amygdala and increases maternal aggression in Sprague–Dawley rats [Abstract] Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1995;21:766.7. [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Knapp DJ, Noonan LR. Prenatal exposure to cocaine treatment alters ultrasonic vocalizations to air puffs in adult female rat offspring [Abstract] Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1994;20(250):21. [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Lubin DA, Walker CH, Meter KE, Mason GA. Chronic gestational cocaine treatment decreases oxytocin levels in the medial preoptic area, ventral tegmental area and hippocampus in Sprague–Dawley rats. Neuropeptides. 1997;31:439–443. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(97)90037-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Means MJ, Anderson DR, Bass EW, Means LW, McMillen BA. Prenatal exposure to cocaine: II. Effects on open field activity and cognitive behavior in Sprague–Dawley rats. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1992;14:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(92)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Means MJ, Bass EW, Means LW, Zimmerman LI, McMillen BA. Prenatal exposure to cocaine: Effects on aggression in Sprague–Dawley rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 1994;27:227–239. doi: 10.1002/dev.420270405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Nelson CJ, Meter KE, Lubin DA, Couch CD, Ayers A, et al. Dose-dependent effects of multiple acute cocaine injections on maternal behavior and aggression in Sprague–Dawley rats. Developmental Neuroscience. 1998;20:525–532. doi: 10.1159/000017353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Noonan LR. Prenatal cocaine exposure affects social behavior in Sprague–Dawley rats. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1995;17:569–576. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(95)00017-l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Noonan LR, Zimmerman LI, Li L, Pedersen CA. Effects of chronic and acute cocaine on the onset of maternal behavior and aggression in Sprague–Dawley rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1994;108:107–112. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns JM, Noonan LR, Zimmerman LI, McMillen BA, Means LW, Walker CH, et al. Chronic cocaine treatment alters social/aggressive behavior in Sprague–Dawley rat dams and their prenatally exposed offspring. In Harvey, J. A., & Kosofsky, B. E. (Eds.), Cocaine: Effects on the developing brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;846:399–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HL, Rosen TS. Mother–infant interaction in a multirisk population. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1990;60:281–288. doi: 10.1037/h0079181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsley CH, Turco D, Bauer A, Beverly M, Wellman J, Graham AL. Cocaine alters the onset and maintenance of maternal behavior in lactating rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1994;47:857–864. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig JFR, Klippel RA. The rat brain: A stereotaxic atlas of the forebrain and lower parts of the brain stem. New York: Krieger; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Koren G, Nulman I, Rovet J, Greenbaum R, Loebstein M, Einarson T. Long-term neurodevelopmental risks in children exposed in utero to cocaine. In: Harvey JA, Kosofsky BE, editors. Cocaine: Effects on the developing brain. Vol. 846. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences; 1998. pp. 306–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Caldji C, Sharma S, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Influence of neonatal rearing conditions on stress-induced adrenocorticotropin responses and norepinephrine release in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2000;12:5–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin DA, Elliott JC, Black MC, Johns JM. An oxytocin antagonist infused into the central nucleus of the amygdala increases maternal aggressive behavior. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;117:195–201. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin DA, Meter KE, Walker CH, Johns JM. Dose-related effects of chronic gestational cocaine treatment on maternal aggression in rats on Postpartum Days 2, 3, and 5. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychology. 2001;25:1403–1420. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer AD, Rosenblatt JS. A method for regulating the duration of pregnancy and the time of parturition in Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River CD strain) Developmental Psychobiology. 1998;32:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numan M. Maternal behavior. In: Knobil E, Neill JD, editors. The physiology of reproduction. 2. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 221–301. [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet DH, Moy SS, Lubin DA, Gause LR, Lieberman JA, Johns JM. Enduring effects of prenatal cocaine administration on emotional behavior in rats. Physiology and Behavior. 2000;70:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00245-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CA, Ascher JA, Monroe YL, Prange AJ. Oxytocin induces maternal behavior in virgin female rats. Science. 1982 May 7;216:648–650. doi: 10.1126/science.7071605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CA, Boccia ML. Oxytocin links mothering received, mothering bestowed and adult stress responses. Stress. 2002;5:259–267. doi: 10.1080/1025389021000037586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CA, Caldwell JD, Johnson MF, Fort SA, Prange AJ. Oxytocin antiserum delays onset of ovarian-steroid induced maternal behavior. Neuropeptides. 1985;6:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(85)90108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CA, Caldwell JD, Walker C, Ayers G, Mason GA. Oxytocin activates the postpartum onset of rat maternal behavior in the ventral tegmental and medial preoptic areas. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1994;108:1163–1171. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.6.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]