Abstract

A capillary electrophoresis competitive immunoassay was developed for simultaneous quantitation of insulin, glucagon, and islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) secretion from islets of Langerhans. Separation buffers and conditions were optimized for resolution of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled glucagon and IAPP immunoassay reagents, which were excited with the 488 nm line of an Ar+ laser and detected at 520 nm with a photomultiplier tube (PMT). Cy5-labeled insulin immunoassay reagents were excited by a 635 nm laser diode module and detected at 700 nm with a separate PMT. Optimum resolution was achieved with a 20 mM carbonate separation buffer at pH 9.0 using a 20 cm effective separation length with an electric field of 500 V/cm. Limits of detection for insulin, glucagon, and IAPP were 2, 3, and 3 nM, respectively. This method was used to monitor simultaneous secretion of these peptides from as few as 14 islets after incubation in 4, 11, and 20 mM glucose for 6 hours. For insulin and IAPP, a statistically significant increase in secretion levels was observed, while glucagon levels were significantly reduced in the 4 and 11 mM glucose conditions. To further demonstrate the utility of the assay, the Ca2+-dependent secretion of these peptides was demonstrated which agreed with published reports. The ability to examine the secretion of multiple peptides may allow for determination of regulation of secretory processes within islets of Langerhans.

Keywords: capillary electrophoresis, immunoassay, multi-analyte, islet of Langerhans

1. Introduction

Glucose homeostasis is a complex process that if unregulated, leads to various metabolic diseases including type 2 diabetes mellitus. A key step in glucose regulation is the release of hormones from islets of Langerhans located in the pancreas. Islets of Langerhans are composed of multiple cell types with each cell type releasing one or more peptides that play a role in glucose regulation. For example, during fasting, α-cells release glucagon to promote hepatic production of glucose from glycogen, thereby maintaining a supply of glucose [1, 2]. Upon an increase in postprandial glucose levels, β-cells release insulin, which in turn, stimulates glucose uptake in peripheral tissues, catabolic inhibition of fatty acid synthesis, inhibition of gluconeogenesis in the liver, and inhibition of glucagon secretion from α-cells [3]. Other peptides are also released from pancreatic β-cells, including the 37-amino acid islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), whose physiological role is still unclear although it has been shown to slow gastric emptying [4]. Interest in IAPP has risen as IAPP can result in insoluble fibrils that form amyloid plaques within diabetic islets. While these fibrils were initially thought to induce β-cell apoptosis [5], newer evidence suggests cell death is due to IAPP oligomers, a form of IAPP somewhere between monomeric and fibril [6–8]. The mechanisms regulating the formation of IAPP oligomers are unknown.

Overall blood glucose is regulated through the release of these numerous peptides, as well as others not mentioned above. Since these peptides are involved in multiple autocrine and paracrine interactions within the islet that influence their own, and each others, secretion, it would be ideal to have a method that could simultaneously monitor secretion of these peptides. This method would aid in understanding the complex intra- and inter-islet relationships that regulate their release.

Common methods for monitoring secretory biomolecules are capillary electrophoresis (CE) immunoassays [9–14]. It is possible to multiplex CE immunoassays for simultaneous detection of multiple analytes since the antibodies confer the specificity necessary to identify each particular analyte [15–18]. Typically in these multi-analyte immunoassays, the signals from the analytes in a single run are similar, which allows for a single detection channel to be used, if the separation resolution is sufficient for quantitation of the peaks. However, due to insulin being released at ~100-fold higher levels than other peptides, more complicated 2-dimensional separations have been required to measure insulin simultaneously with other peptides [19]. Previously, we developed a capillary electrophoresis immunoassay for the simultaneous detection of insulin and glucagon using a single separation dimension [20]. Separate detection channels for insulin and glucagon reagents were required due to the higher levels of insulin present as compared to glucagon.

In this report, we describe a simultaneous capillary electrophoresis competitive immunoassay to monitor insulin, glucagon, and IAPP secreted from islets of Langerhans. Due to the large amounts of insulin present, detection of the insulin immunoassay reagents was made with a Cy5 fluorophore using a 635 nm laser. Glucagon and IAPP have similar concentrations and their immunoassay reagents were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and excited with a 488 nm laser. Separation of these reagents was optimized to allow simultaneous quantitation, and the secreted amounts of each of these analytes were monitored from as few as 14 islets. The ability to investigate intra- and inter-islet signaling mechanisms was demonstrated by examining the Ca2+-dependent secretion of these peptides.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Porcine glucagon (G3157) and monoclonal antibody (Ab) to glucagon from mouse ascites fluid (clone K79bB10, Kd = 1.6 nM), bovine insulin, Tween-20, phosphate buffered saline (PBS), sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, and sodium phosphate monobasic were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). A monoclonal Ab to human insulin C-terminal (E86211M, Kd = 1 nM) was obtained from Meridian Life Science, Inc (Saco, ME). Mouse IAPP and a rabbit anti-rat IAPP antiserum IgG fraction (T-4145) were from Bachem Americas, Inc (Torrance, CA). FITC-IAPP (IAPP*) and FITC-glucagon (Glu*) were custom-synthesized by CHI Scientific, Inc (Maynard, MA) using the mouse and porcine amino acid sequences, respectively. Cy5 monofunctional N-hydroxysuccinimide ester was obtained from GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences (Piscataway, NJ). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were from EMD Chemicals (San Diego, CA). All islet isolation materials were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich unless otherwise stated. All solutions were prepared using ultrapure deionized water (NANOpure® Diamond™ deionization system, Barnstead International, Dubuque, IA).

2.2 Cy5 labeling and purification of Cy5-labeled insulin

Insulin from bovine pancreas was labeled with Cy5 according to manufacturer instructions. Briefly, insulin was dissolved at 1 mg/mL in bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.3. 1 mL of this solution was added to the Cy5 dye vial and mixed thoroughly for 1 min. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark with mixing every 10 min. Cy5-labeled insulin (Ins*) was separated from unconjugated dye using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare BioSciences). Ins* was eluted with PBS and 500 mL fractions were collected, and the concentration of each fraction determined by UV–Vis absorbance using the molar extinction coefficient of insulin [21] (ε = 6000 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm) and Cy5 (ε = 250000 M−1 cm−1 at 650 nm). Due to the multiple labeling sites present on insulin, the three most concentrated fractions were purified by HPLC. A Waters Symmetry300 C4 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) was used with an isocratic mobile phase consisting of 30% acetonitrile/70% water with 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid. All peaks separated and detected by HPLC were collected and tested for their reactivity to the insulin Ab by CE. The most reactive fraction was kept and quantified using UV-Vis absorbance.

2.3 Capillary electrophoresis

CE was performed with a P/ACE MDQ CE instrument (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) mounted with a dual-wavelength LIF detector. A 3 mW argon-ion laser (Beckman) and a 25 mW Radius 635 laser diode module (Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) were used as excitation sources (488 and 635 nm, respectively). After excitation of the analytes through the capillary detection window, the emission wavelengths were split by a half-silvered mirror at a 50:50 ratio and directed through either a 520 ± 20 nm bandpass or a 663 nm longpass filter prior to detection by separate photomultiplier tubes (PMTs). Data were acquired at 16 Hz and analyzed using 32Karat software (Beckman Coulter). Separations were performed in a 50μm i.d. × 360 μm o.d., 30 cm (20 cm effective length) fused-silica capillary (Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ) maintained at 20°C. At the beginning of each day, the capillary was rinsed with 1 M NaOH for 5 min, and deionized water for 2 min at 60 psi. The capillary was then conditioned with the run buffer for 5 min at 60 psi. Between analyses, the capillary was rinsed with 1 M NaOH and run buffer for 1 min at 60 psi. Samples were injected by applying 0.5 psi for 10 sec. Separation was performed at 15 kV with a 1 min voltage ramp time.

2.4 Sample preparation

Immunoassay reagents were prepared in 20 mM NaH2PO4, 1mM EDTA pH 7.4, with 1 mg/mL BSA, and 0.1% w/v Tween 20 (sample buffer). Peptide standards were dissolved in either RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or balanced salt solution (125 mM NaCl, 5.9 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2.4 mM CaCl2, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 with 1 mg/mL BSA) as stated in the text. Final samples contained a mixture of Ins*, Glu*, IAPP*, anti-insulin antibody (AbIns), anti-glucagon antibody (AbGlu) and anti-IAPP antibody (AbIAPP) at concentrations given in the text. Calibration curves were obtained using 100 nM Ins*, 10 nM Glu*, 10 nM IAPP*, 50 nM AbIns, 40 nM AbGlu, 300 nM AbIAPP, 0–500 nM unlabeled insulin (Ins), 0–50 nM unlabeled glucagon (Glu), and 0–50 nM IAPP, in 10 μL. In each of these standards, 3 μL of the 10 μL reaction mixture was either RPMI 1640 media or balanced salt solution and the other 7 μL was sample buffer. The mixtures of antigens and antibodies were incubated for 10 min in the dark at room temperature before analysis.

2.5 Islet of Langerhans isolation and culture

Islets of Langerhans were collected from male mice as previously described [22, 23]. After isolation, islets were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 media containing 10% FBS and 11 mM glucose. Islets were used within 5 days after isolation.

2.6 Static incubation of islets of Langerhans

For measurement of insulin, IAPP, and glucagon secretion, 14 islets were washed and placed in 10μL of RPMI 1640 containing 4, 11, or 20 mM glucose and held in an incubator at 37 °C, 5% CO2. In the Ca2+-dependent study, 15 islets were incubated in 10 μL in a calcium-deprived balanced salt solution containing 4 or 20 mM glucose and in an equivalent media containing 2.4 mM Ca2+. After 6 hours, 3μL of the supernatant was removed and diluted with 10μL of sample buffer that contained the appropriate amounts of reagents to produce the same concentrations of AbIns, AbGlu, AbIAPP, Ins*, Glu*, and IAPP* that were used in the calibration curves. Each of these incubations was repeated 4 times.

2.7 Data analysis

Peak heights of the bound (B) and free (F) labeled reagents were found using the 32 Karat software supplied with the CE instrument. Peak resolution was determined by fitting Gaussian curves and finding the peak widths from these idealized curves since baseline resolution was not achieved. All calibration data are shown as the mean ± 1 standard deviation of the B/F ratio (n = 3). A weighted four parameter logistic model was fit to each set of calibration data and all fits had adjusted r2 > 0.99. Limits of detection were determined by the concentration of unlabeled antigen that would produce a B/F ratio equal to the B/F of the blank runs minus three times the standard deviation of the blank [13]. For the biological results, the concentrations of each antigen were quantified using the four parameter logistic curve, converted to mass, and normalized to the time and number of islets present in the incubation media. These results are presented as the standard error of the mean from four experiments. Statistical significance was tested with a 2-tailed Student’s t-test and results were deemed significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

To obtain a complete picture of islet of Langerhans physiology, it is desirable to monitor the release of multiple peptides simultaneously. Previously, we developed a capillary electrophoresis competitive immunoassay for insulin and glucagon and used it to measure the amount of these peptides within islets of Langerhans [20]. A two-color detection scheme was used to separate the signals from each analyte, since insulin levels are approximately ~100-fold higher than glucagon. We have now extended this assay to include the peptide IAPP, which is co-released with insulin from pancreatic β-cells, albeit at similar levels as glucagon [24, 25].

The first change made from our previous report [20] of the insulin and glucagon assay was to label glucagon and IAPP with FITC and insulin with Cy5. With this change, the longer wavelength dye was used for the detection of the higher concentration analyte and reduced the spectral crosstalk between the detection channels. At the concentration of the analytes we used, there was no detectable crosstalk between the detection channels and therefore, no correction was used throughout the data analysis. Since glucagon and IAPP have similar secretory levels, the use of a new detection wavelength was not necessary. The inclusion of the IAPP assay to our previous dual analyte assay necessitated finding the optimum separation conditions for IAPP* and its antibody, followed by inclusion of insulin and glucagon immunoassay reagents and re-optimization of the separation parameters to find conditions that would separate all immunoaffinity reagents.

3.1 Development of IAPP immunoassay

A polyclonal antibody to rodent IAPP was used, as monoclonal antibodies were not available from a commercial source. As will be described in section 3.2 below, the working concentration of AbIAPP was found by varying the concentration of AbIAPP which produced a detectable AbIAPP:IAPP* complex peak while still maintaining a sensitive assay.

Initially, separation of the free IAPP* and bound AbIAPP:IAPP* was attempted with the buffer used in the previous report (20 mM borate, pH 9.3), but was unsuccessful. After attempting a variety of other buffers with limited success, the conditions that allowed the highest resolution of bound AbIAPP:IAPP* and free IAPP* in the shortest time was a 20 mM bicarbonate buffer at pH 10 with a 10 cm separation length.

3.2 Incorporation of IAPP immunoassay with insulin and glucagon assays

After optimization of the IAPP separation conditions, AbGlu and Glu* were included to determine if the two immunoassays in the FITC detection channel could be resolved. Although the pH 10 bicarbonate buffer was ideal for resolution of the IAPP immunoassay components alone, this buffer did not adequately resolve the AbIAPP:IAPP* and AbGlu:Glu* peaks. Acceptable resolution between the two complex peaks was achieved by lowering the pH from 10 to 9.0, and increasing the separation distance from 10 to 20 cm (Figure 1). However, due to the relatively long separation length, significant dissociation of the AbGlu:Glu* peak occurred during the separation such that the B/F ratio of the glucagon assay was ≪1 without addition of unlabeled Glu. Having such a low initial point in the calibration curve reduced the sensitivity and dynamic range of the glucagon immunoassay to a point where it was not useful. Although the increased separation length likely reduced the AbIAPP:IAPP* and AbIns:Ins* peaks as well, the problem was particularly severe for the glucagon assay.

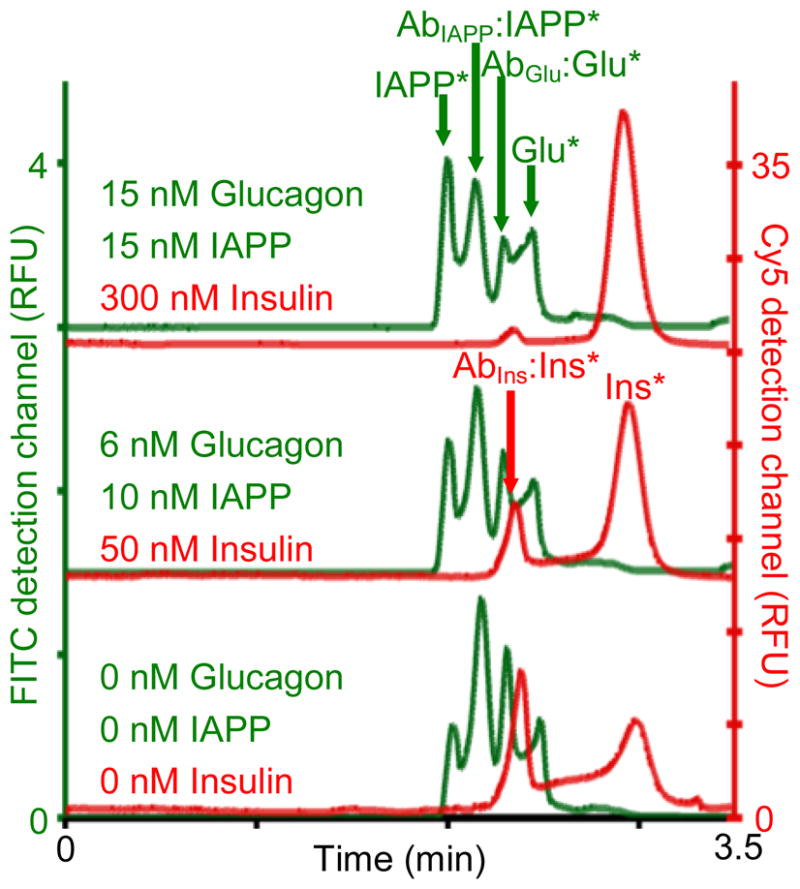

Figure 1. Simultaneous electropherograms of IAPP, glucagon, and insulin.

IAPP and glucagon (green traces) were detected in FITC detection channel (left y-axis) and insulin (red traces) was detected in Cy 5 detection channel (right y-axis). Each sample had 100 nM Ins*, 10 nM Glu*, 10 nM IAPP*, 50 nM AbIns, 40 nM AbGlu, 300 nM AbIAPP and the amount of unlabeled IAPP, Glu, and Ins as indicated in the figure. Injection was performed by applying 0.5 psi for 10 sec followed by separation at 15 kV with a 1 min voltage ramp time. The electropherograms were offset for clarity.

One solution to prevent dissociation of the bound AbGlu:Glu* peak was to increase the amount of the immunoassay reagents injected into the capillary by increasing the injection volume [26], but this led to lower resolution for all peaks. We also attempted to lower the separation temperature, but this also failed to maintain a suitable complex peak. A solution to the problem was found by increasing the amount of AbGlu used in the binding assay. The ratio of AbGlu:Glu* was raised to 4:1 (mole:mole), which provided a B/F ~ 2 with no Glu added. Due to the presence of an unknown concentration of high affinity antibodies in the antiserum, the AbIAPP:IAPP* ratio (30:1 mole:mole) was optimized experimentally. Very little change in the B/F ratio of insulin was observed over a number of separation conditions. The major disadvantages to increasing the ratio of antibody:labeled antigen are lower sensitivities and smaller dynamic ranges of the assays; however, as it will be shown below, the assays were able to detect secretion of the analytes from a small number of islets.

Shown in Figure 1 are separations of three immunoassay standards at the indicated concentration of unlabeled reagents. The bound AbIns:Ins* peak and free Ins* peaks were well separated in the Cy5 detection channel (red traces corresponding to the right y-axis) for all concentrations tested. In the FITC channel (left y-axis), the resolution of the bound AbIAPP:IAPP* and free IAPP* peaks was 0.95 ± 0.02 over all concentrations of IAPP tested, while the resolution for the glucagon immunoassay peaks was 0.74 ± 0.03 for all concentrations of glucagon tested. It is possible that bivalent complexes of the AbGlu are present between the Glu* and AbGlu:Glu* peaks shown in Figure 1; however, although baseline resolution of the glucagon peaks was not achieved, quantitation of both glucagon and IAPP was not hindered. Since the detector gain was optimized for each detection channel independently, it is important to note that the insulin reagents would obscure the glucagon and IAPP reagents if a single detection channel were used.

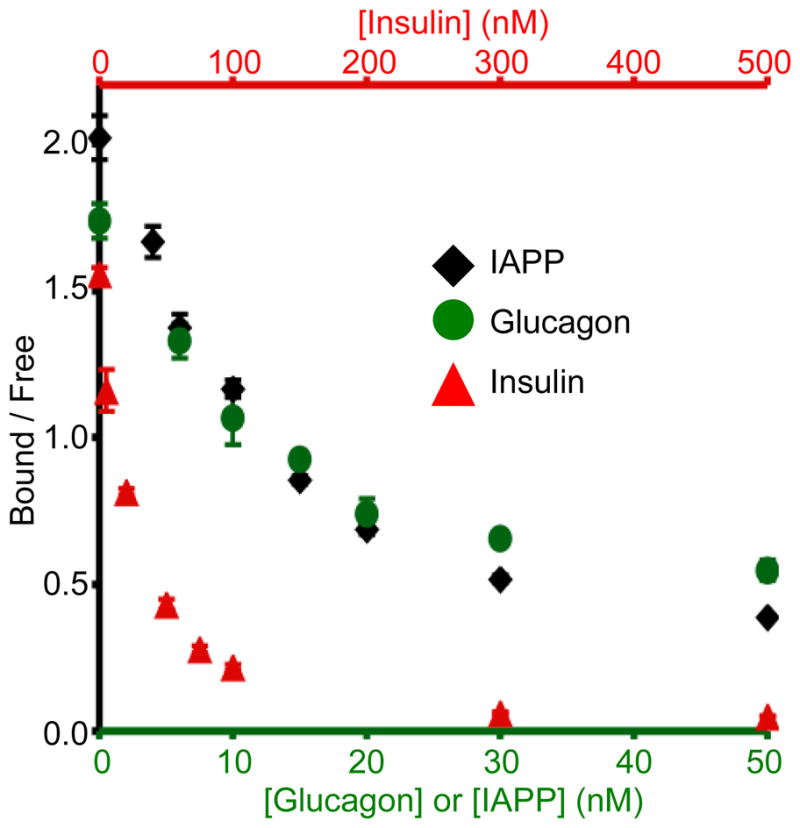

After optimizing the separation of the immunoassay reagents, simultaneous calibration curves over the concentration range expected to be observed in the secretion assays were made. Figure 2 shows the calibration curves obtained for each analyte during simultaneous runs. Concentrations of IAPP and glucagon tested are shown on the bottom x-axis and the insulin concentrations on the top x-axis. Weighted four parameter logistic fits to the curves were performed and used to determine limits of detection of the three analytes as described in Section 2.7. The limits of detection for insulin, glucagon, and IAPP were 2, 3, and 3 nM, respectively. As described above, the limits of detection of the glucagon and IAPP assays may have been increased by the large amount of antibodies used. Nevertheless, these detection limits allowed us to utilize this assay for simultaneous measurement of the secretion of these three analytes.

Figure 2. Calibration curves of IAPP, glucagon, and insulin competitive immunoassays.

Concentrations of immunoassay reagents are given in the text and the amounts of unlabeled IAPP, glucagon, and insulin were varied as shown on the x-axes (glucagon and IAPP on bottom x-axis and insulin on top x-axis). Peak heights of bound and free IAPP* (black diamond), Glu* (green circle), and Ins* (red triangle) were quantified from electropherograms like those shown in Figure 1 and the B/F ratio shown on the y-axis. Average values are plotted (n = 3) with error bars corresponding to +/− 1 standard deviation.

3.3 Measurement of insulin, glucagon, and IAPP secretion from islets of Langerhans

Development of assays aimed at monitoring simultaneous secretion of multiple peptides is important, as the numerous processes controlling the release of these peptides are still unknown. Glucagon is released under low glucose concentrations to initiate hepatic breakdown of glycogen to glucose. Upon increases in extracellular glucose, insulin secretion is initiated and glucagon levels fall, both processes helping to lower blood glucose levels. IAPP, which is co-secreted with insulin, increases with increasing glucose concentrations. Although these general trends are well known, the intracellular mechanisms controlling the release are still under investigation and will likely benefit from having an assay available that can measure the three analytes simultaneously.

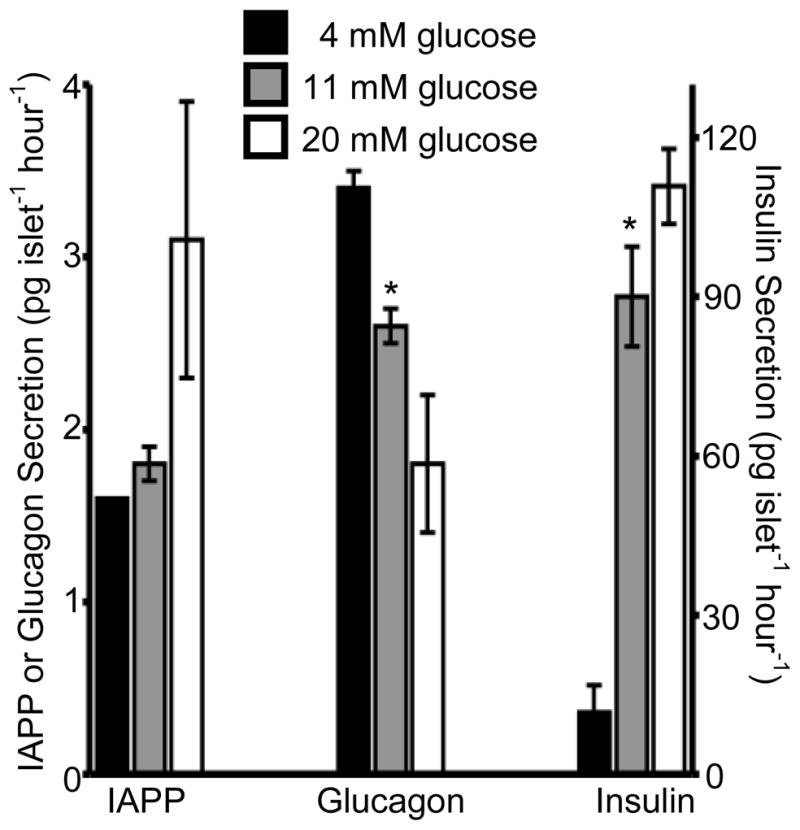

Batches of islets were incubated for 6 hours in 4, 11, and 20 mM glucose prior to measurement of their secreted peptides. As shown in Figure 3, insulin and IAPP secretion increased, and glucagon decreased, as the glucose concentration in the incubation medium increased. These results were in accordance with the well-known trends described above. Insulin levels were 11.6 ± 5.2, 90.0 ± 9.4, and 110.8 ± 7.1 pg islet−1 hour−1 at 4, 11 and 20 mM glucose, respectively. Glucagon values were 3.4 ± 0.1, 2.6 ± 0.1, and 1.8 ± 0.4 pg islet−1 hour−1 at the same glucose values. IAPP secretory levels at 4 mM glucose were below the LOD in 3 samples and 1.6 pg islet−1 hour−1 in one sample. IAPP secretion increased to 1.8 ± 0.1 and 3.1 ± 0.8 pg islet−1 hour−1 at 11 and 20 mM glucose, respectively. The difference in the secretory levels was statistically significant to varying degrees as shown in Figure 3. These measured values are within ranges that have been reported in the literature using more conventional techniques [24, 25, 27, 28]. Incubation times longer than 6 hours led to islet death, which produced an increase in the values of all peptides measured due to cell lysis.

Figure 3. IAPP, glucagon, and insulin secretion in response to varying glucose levels.

Batches of 14 islets were incubated in 4 (black bars), 11 (grey bars), and 20 (white bars) mM glucose and the levels of IAPP, glucagon, and insulin secretion were measured after 6 hours of incubation. Average values are plotted (n = 4) with error bars corresponding to +/− 1 standard error of the mean. IAPP and glucagon values are shown on the left y-axis and insulin values are shown on the right y-axis.. * = p < 0.05.

3.4 Ca2+-dependence of peptide secretion

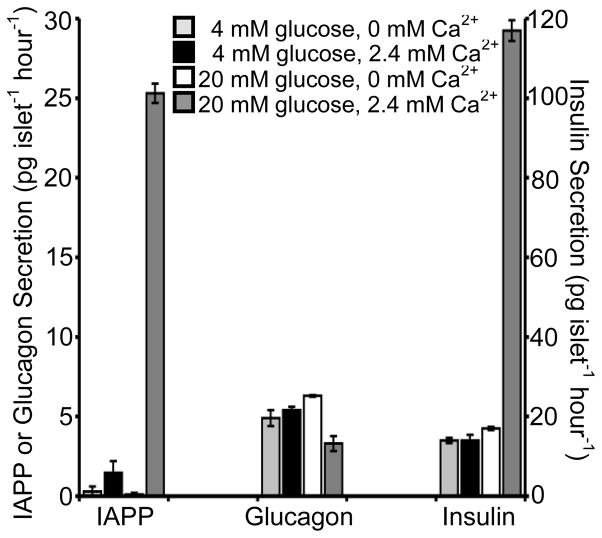

3.4.1 Insulin

It is well known that glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells is dependent on the presence of extracellular Ca2+ [29]. After incubating islets in the presence and absence of Ca2+ in low and high glucose conditions, peptide secretion was measured. As expected, at 20 mM glucose, insulin release was high at 116.9 ± 2.6 pg islet−1 hour−1 in the presence of 2.4 mM Ca2+, but diminished by 86% (p < 0.01) to 16.5 ± 0.2 pg islet−1 hour−1 in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Figure 4). When the experiments were performed at a non-stimulatory glucose level (4 mM), insulin secretion values were similar in the absence (14.0 ± 0.7 pg islet−1 hour−1) and presence (14.1 ± 1.4 pg islet−1 hour−1) of Ca2+ (p > 0.05). The results obtained for insulin matched published results for Ca2+-dependent insulin release [30].

Figure 4. Ca2+-dependence of IAPP, glucagon, and insulin secretion.

Insulin, IAPP, and glucagon secretion was measured from 15 islets in 4 mM glucose with 0 mM extracellular Ca2+ (light grey bars), 4 mM glucose with 2.4 mM extracellular Ca2+ (black bars), 20 mM glucose with 0 mM extracellular Ca2+ (white bars), and 20 mM glucose with 2.4 mM extracellular Ca2+ (dark grey bars). Average values of four replicate experiments are given with the error bars corresponding to +/− 1 standard error of the mean. IAPP and glucagon values are shown on the left y-axis and insulin values are shown on the right y-axis.

3.4.2 IAPP

In adult rat islets, IAPP secretion is regulated through a Ca2+-dependent process [31, 32]. As seen in Figure 4, we also observed Ca2+-dependent IAPP secretion. In the presence of Ca2+, IAPP secretion increased from 1.5 ± 0.7 pg islet−1 hour−1 at 4 mM glucose to 25.3 ± 0.6 pg islet−1 hour−1 in 20 mM glucose (p < 0.01). However, in the absence of Ca2+, IAPP release was measured in only one replicate of islets (out of 4 total replicates) at 4 mM glucose with a value of 1.2 pg islet−1 hour−1, but undetectable at 20 mM glucose. The secretion of IAPP therefore appears to be Ca2+-dependent in mice as well as in rats.

3.4.3 Glucagon

In contrast to insulin and IAPP, the signaling pathways regulating glucagon release from α-cells are less clear. It has been observed that α-cells are electrically active [33] and contain electrically active Ca2+ channels [34]. Several reports have indicated that entry of extracellular Ca2+ is required for glucagon release, whereas others have reported that glucagon can be released in the absence of Ca2+ [35 – 37]. Adding to the confusion is the inhibition of glucagon release from as yet unknown islet-derived factors, including insulin [38] or Zn2+ [39]. Further complicating these studies is that these islet-derived factors have their own Ca2+-dependency. Ideally, simultaneous measurement of multiple peptides from islets will aid in clarifying this process.

As shown in Figure 4, in the presence of Ca2+, glucagon secretion was higher at 5.4 ± 0.2 pg islet−1 hour−1 in 4 mM glucose compared to 3.3 ± 0.5 pg islet−1 hour−1 at 20 mM glucose (p < 0.01), similar to the trend found in Section 3.3. In the absence of Ca2+, glucagon secretion was 4.9 ± 0.5 pg islet−1 hour−1 at 4 mM glucose, but the levels increased ~30% in 20 mM glucose to 6.3 ± 0.1 pg islet−1 hour−1 (p < 0.05). While we initially expected that removal of Ca2+ would block secretion of glucagon, perhaps the dramatic decline in insulin and IAPP levels, both known to inhibit glucagon secretion [28], may contribute to its increased release in this extreme condition. Or glucagon may be released through a non-exocytotic process in the absence of Ca2+ [36] which would result in increased levels detected in this condition.

4. Conclusion

Development of a simultaneous immunoassay for peptide secretion from islets of Langerhans will aid in delineating the multiple mechanisms involved in glucose regulation. The 3-analyte immunoassay described here was expanded from our initial report for a simultaneous assay for insulin and glucagon by including an assay for IAPP in the FITC detection channel. While inclusion of more analytes makes the optimization of separation conditions more difficult, the ability to measure IAPP simultaneously with glucagon and insulin compensate for this difficulty. With this assay, measurement of secretion was possible from as few as 14 islets. To further demonstrate the applicability of the assay for biological measurements, the Ca2+-dependent nature of insulin, IAPP, and glucagon secretion was also measured. Improvements to the assay will focus on increasing the sensitivity of the glucagon and IAPP assays, by either reducing complex dissociation or through higher affinity binding agents. In the future, measurement of other peptides could be performed in either the Cy5 or FITC channel, or more detection channels could be added.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (R01 DK080714). The authors would like to thank Ashley Sidebottom and Joseph Duren for initial testing of binding conditions for IAPP to its antibody.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gromada J, Franklin I, Wollheim CB. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:84. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson RP. Diabetes. 2010;59:2735. doi: 10.2337/db10-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Nature. 2001;414:799. doi: 10.1038/414799a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnelo U, Permert J, Larsson J, Reidelberger RD, Arnelo C, Adrian TE. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4081. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenzo A, Razzaboni B, Weir GC, Yankner BA. Nature. 1994;368:756. doi: 10.1038/368756a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritzel RA, Meier JJ, Lin CY, Veldhuis JD, Butler PC. Diabetes. 2007;56:65. doi: 10.2337/db06-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haataja L, Gurlo T, Huang CJ, Butler PC. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:303. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brender JR, Lee EL, Cavitt MA, Gafni A, Steel DG, Ramamoorthy A. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6424. doi: 10.1021/ja710484d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schultz NM, Kennedy RT. Anal Chem. 1993;65:3161. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tao L, Aspinwall CA, Kennedy RT. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:403. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heegaard NHH, Kennedy RT. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3122. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991001)20:15/16<3122::AID-ELPS3122>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu CM, Tung KH, Chang TH, Chien CC, Yen MH. J Chromatogr B. 2003;791:315. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(03)00249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roper MG, Shackman JG, Dahlgren GM, Kennedy RT. Anal Chem. 2003;75:4711. doi: 10.1021/ac0346813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moser AC, Hage DS. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:3279. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen FTA, Evangelista RA. Clin Chem. 1994;40:1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caslavska J, Allemann D, Thormann W. J Chromatogr A. 1999;838:197. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy BM, He X, Dandy D, Henry CS. Anal Chem. 2008;80:444. doi: 10.1021/ac7019046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang W, Yu M, Sun X, Woolley AT. Lab Chip. 2010;10:2527. doi: 10.1039/c005288d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.German I, Roper MG, Kalra SP, Rhinehart E, Kennedy RT. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:3659. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200109)22:17<3659::AID-ELPS3659>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillo C, Roper MG. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:410. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larson JL, Miranker AD. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:221. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Roper MG. Anal Chem. 2009;81:1162. doi: 10.1021/ac802579z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao L, Zhang X, Grimley A, Lomasney A, Roper MG. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;398:1985. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4168-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlsson E, Stridsberg M, Sandler S. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56:1339. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasa R, Gomis R, Casamitjana R, Novials A. Pancreas. 2001;22:307. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lomasney AR, Guillo C, Sidebottom AM, Roper MG. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;394:313. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2622-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlsson E, Stridsberg M, Sandler S. Regul Pept. 1996;63:39. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(96)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Åkesson B, Panagiotidis G, Westermark P, Lundquist I. Regul Pept. 2003;111:55. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satin LS. Endocrine. 2000;13:251. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:13:3:251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henquin JC. Diabetes. 2000;49:1751. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verchere CB, D’Alessio DA, Prigeon RL, Hull RL, Kahn SE. Diabetes. 2000;49:1477. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marzban L, Trigo-Gonzalez G, Verchere CB. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2154. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braun M, Rorsman P. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1827. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1823-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanno T, Göpel SO, Rorsman P, Wakui M. Neurosci Res. 2002;42:79. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leclercq-Meyer V, Marchand J, Malaisse WJ. Diabetologia. 1976;12:531. doi: 10.1007/BF01219520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carpentier JL, Malaisse-Lagae F, Müller WA, Orci L. J Clin Invest. 1977;60:1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI108870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leclercq-Meyer V, Marchand J, Malaisse WJ. Am J Physiol. 1979;236:E98. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.236.2.E98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravier MA, Rutter GA. Diabetes. 2005;54:1789. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slucca M, Harmon JS, Oseid EA, Bryan J, Robertson RP. Diabetes. 2010;59:128. doi: 10.2337/db09-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]