Abstract

Maternal defense (offspring protection) is a critical and highly conserved component of maternal care in mammalian systems that involves dramatic shifts in a female’s behavioral response to social cues. Numerous changes occur in neuronal signaling and connectivity in the postpartum female, including decreases in norepinephrine (NE) signaling in subregions of the CNS. In this study using a strain of mice selected for maternal defense, we examined whether possible changes in NE signaling in the lateral septum (LS) could facilitate expression of maternal aggression. In separate studies that utilized a repeated measures design, mice were tested for maternal defense following intra-LS injections of either the β adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol (10 μg or 30 μg) or vehicle (Experiment 1), the β-adrenergic receptor antagonist propranolol (2 μg) or vehicle (Experiment 2), or the β1 receptor antagonist, atenolol (Experiment 3). Mice were also evaluated for light-dark performance and pup retrieval. 30 μg of the agonist isoproterenol significantly decreased number of attacks and time aggressive relative to vehicle without affecting pup retrieval or light/dark box performance. In contrast, the antagonist propranolol significantly increased maternal aggression (lowered latency to attack and increased total attack time) without altering light/dark box test. The β1 specific antagonist, atenolol, significantly decreased latency to attack (1 μg v. vehicle) without altering other measures. Although the findings were identified in a unique strain of mice that may or may not apply to other strains, the results of these studies support the hypothesis that changes in NE signaling in LS during the postpartum period contribute to the expression of offspring protection.

Keywords: adrenergic, isoproterenol, maternal aggression, norepinephrine, propranolol

Introduction

In many mammalian species, parturition and lactation are accompanied by a variety of behavioral changes in the maternal female that help to facilitate the survival of offspring. Postpartum females exhibit shifts in response to stressors and social cues (Gammie et al., 2008; Lightman, 1992; Liu et al., 2001; Neumann et al., 1998; Toufexis et al., 1998; Toufexis and Walker, 1996) that include the emergence of aggression toward intruders as a means for protecting vulnerable offspring (Lonstein and Gammie, 2002). During lactation, changes occur in release of neuromodulators (e.g., oxytocin, corticotropin-releasing factor, GABA) (Bosch et al., 2004; Qureshi et al., 1987; Walker et al., 2001) and links exist between these signaling molecules and maternal defense expression (Bosch et al., 2005; Gammie et al., 2004; Lee and Gammie, 2007). Norepinephrine (NE) also shows differing release in the postpartum period (Toufexis et al., 1999; Toufexis et al., 1998; Toufexis and Walker, 1996), but little has been done to explore the possibility that changes in NE signaling may contribute to maternal defense.

NE is linked to male aggression (Haden and Scarpa, 2007; Haller and Kruk, 2003; Haller et al., 1998) and in some cases, there is a positive relationship between noradrenergic activity and aggression (fighting/biting), including after exposure to a stressor (Haden and Scarpa, 2007). However, NE depletion or antagonism also promotes aggression as acute peripheral application of propranolol, a β-adrenergic antagonist, increases shock-induced aggression (Matray-Devoti and Wagner, 1993) and sub-chronic administration of this drug increases aggression in a neutral arena (Gao and Cutler, 1992) in male mice. Further, chronic treatment with propranolol can counteract aggression deficits induced by chronic stress (Zebrowska-Lupina et al., 1997) in male rats.

In females, secretion of NE in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus is reduced during lactation and contributes to altered stress reactivity (Toufexis et al., 1999; Toufexis et al., 1998; Toufexis and Walker, 1996). An older study employing the neurotoxin, 6-hydroxydopamine, that would globally decrease both NE and dopamine, found an elevation of maternal aggression (Sorenson and Gordon, 1975). Although it is not possible to parse the effects of dopamine from NE in that study, the finding is consistent with the framework that decreases in NE support offspring protection. Collectively, the data suggest that alterations in NE signaling in particular brain regions could be mechanism for promoting maternal defense.

Lateral septum (LS) is a brain region in which NE could regulate maternal defense. LS has neuronal connections to a number of other brain regions implicated in maternal defense (e.g., bed nucleus of stria terminalis, PVN, central amygdala, lateral hypothalamus, and periaqueductal gray) (Gammie and Lonstein, 2006; Sheehan et al., 2004) and it receives NE input from distant sites including both the locus coeruleus (LC) and medulla (regions where the NE system originates) (Lindvall and Stenevi, 1978). LS is populated by both α and β adrenergic receptor types (Bondi et al., 2007; Carette et al., 2001; Liu and Alreja, 1998; Rainbow et al., 1984) and our lab and others have shown LS to play a role in regulating offspring protection (D’Anna and Gammie, 2009; Flannelly et al., 1986; Lee and Gammie, 2009).

In this study, we investigated the possibility that NE signaling in LS affects maternal aggression in lactating female mice. We focus here on the β receptors because in preliminary studies a clear role for the α receptor was not found (S.C. Gammie, unpublished observations). We performed three experiments to test the possibility that a reduction in NE signaling acting on the β receptors in LS mediates maternal aggression in mice. In the first study, females received LS injections of the general β receptor agonist, isoproterenol, and were also tested for maternal aggression, using a resident intruder model. In the second study, females received microinjections to the LS of either vehicle or the general β receptor antagonist (−) propranolol and were tested for maternal aggression. Pup retrieval was also performed to examine effects on a different active motor behavior and light/dark box test was performed to examine general effects of treatment on anxiety-like behaviors. In the third study, females received microinjections of the β1 specific receptor antagonist, atenolol, and were similarly tested. We hypothesized that if a reduction in NE signaling in LS facilitates maternal aggression, then activating these receptors via isoproterenol would decrease maternal aggression and antagonizing β adrenergic receptors via propranolol or atenolol would increase maternal aggression. This study was designed to provide new insights into the role of NE acting in LS plays in the expression of maternal aggression.

Method

Mice

Female mice selected for high maternal aggression (Gammie et al., 2006) and male outbred hsd: ICR (Harlan, Madison, WI) mice were used in this study. The rationale for using selected mice is that they provide a reliable baseline of aggression that allows for testing of modulators that may either increase or decrease aggression. Mice were housed in polypropylene cages with access to tap water and breeder chow (for females) and regular chow (for males) ad libitum. Females were paired with a breeder male and after 10 days, the male was removed from the cage. On postpartum day (PPD) 3, litters were culled to eleven pups. Outbred, sexually naive male mice were grouped housed and were used as intruders. Intruder males were never used more than once per day and were used for no more than 3 tests each. Cages were changed weekly prior to parturition after which they were unchanged for the remainder of the experiment. All animals were housed on a 14:10 light/dark cycle with lights on at 06:00 CST. All procedures followed the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Wisconsin.

Cannulation Surgeries

On PPD 3, under isoflurane anesthesia and using a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tunjunga, CA), a midline incision across the top of the skull was made. Prior to the cut, the hair above the skull was shaved and the skin cleaned and treated with alcohol and Betadine (Purdue Frederick, Stamford, CT). Sedation from anesthesia was determined by a lack of movement in response to a foot and tail pinch. Based on chemoarchitecture and connections, LS has been divided into rostral, and caudal regions (Risold and Swanson, 1997). The Paxinos mouse brain atlas divides LS into dorsal, ventral, and intermediate (LSi) regions (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001), which is based on local anatomy. For the purposes of this study we targeted LS that included LSd, LSi and LSv; see Figs. 1A, 3A, and 5A for locations of hits to LS. Each injection was within 0.24 mm of the shown section. To perform LS unilateral injections, a small hole was drilled + 0.2 mm posterior and + 0.5 mm lateral to Bregma. In the hole, a 26 gauge stainless-steel indwelling cannula (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) was implanted to −2.5 mm below the skull surface. In some cases, the cannula did not hit LS and misses were analyzed separately. Two small screws were drilled into the skull lateral and anterior to the guide cannula. Each cannula was secured to the skull using dental cement (Plastics One). A dummy cannula was inserted to maintain patency until injections were made using a 33 gauge stainless-steel injector attached to PE-50 tubing (Becton Dickenson, Sparks, MD) fitted to a 10 μL Hamilton syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV). On PPD 3 and 4, a cannula was briefly put into the guide to prepare the tissue for later injections on test days. This approach was used to ensure more consistent conditions of tissue across test days. Before and after surgery, all animals received s.c. injections of ketoprofen (1 mg/kg) to minimize any discomfort.

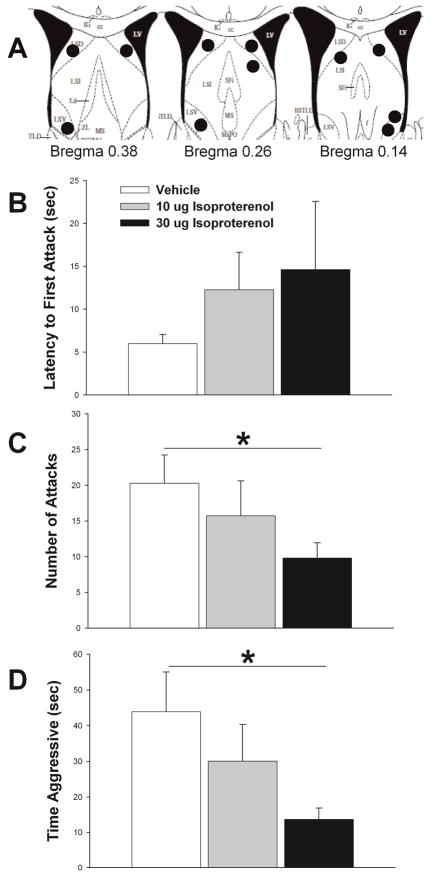

Figure 1.

Effects of β adrenergic receptor agonist, isoproterenol, on maternal defense. A) Schematic representation of cannula hits (black circles) to LS (see Methods for further details). B) Isoproterenol non-significantly increases latency to first attack, but significantly impairs both number of attacks (C) and total time aggressive (D) (see Results for further statistical details). Vehicle treatment results shown in white bars, 10 μg isoproterenol shown in gray bars, and 30 μg of isoproterenol shown in black bars. N = 11, repeated measures testing. Bars indicate mean + SE. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05 between groups. Diagrams in A are adapted from The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (2nd. ed), Paxinos and Franklin, 2001 (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001).

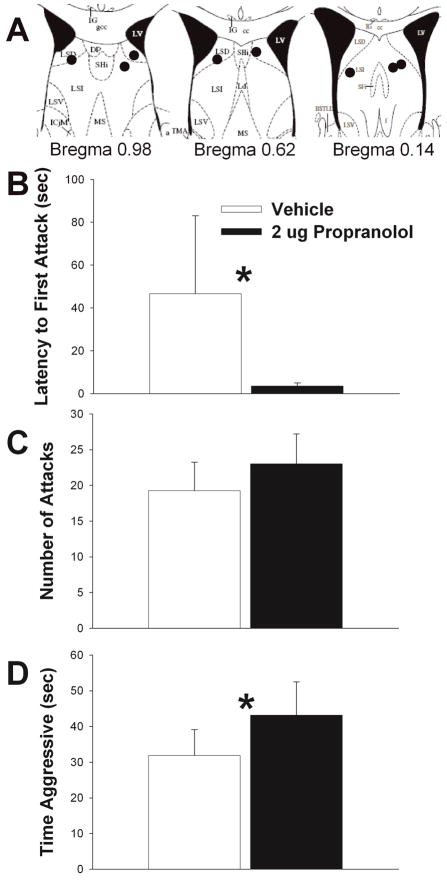

Figure 3.

Effects of β adrenergic receptor antagonist, propranolol, on maternal defense. A) Schematic representation of cannula hits (black circles) to LS (see Methods for further details). B) 2 μg propranolol significantly reduced latency to first attack relative to vehicle. C) Propanolol elevated number of attacks relative to vehicle, but differences were not significant. D) Propranolol significantly elevated total time aggressive relative to vehicle. Vehicle treatment results shown in white bars and 2 μg propranolol shown in black bars. N = 8, repeated measures testing. Bars indicate mean + SE. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05 between groups. Diagrams in A are adapted from Paxinos and Franklin, 2001 (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001).

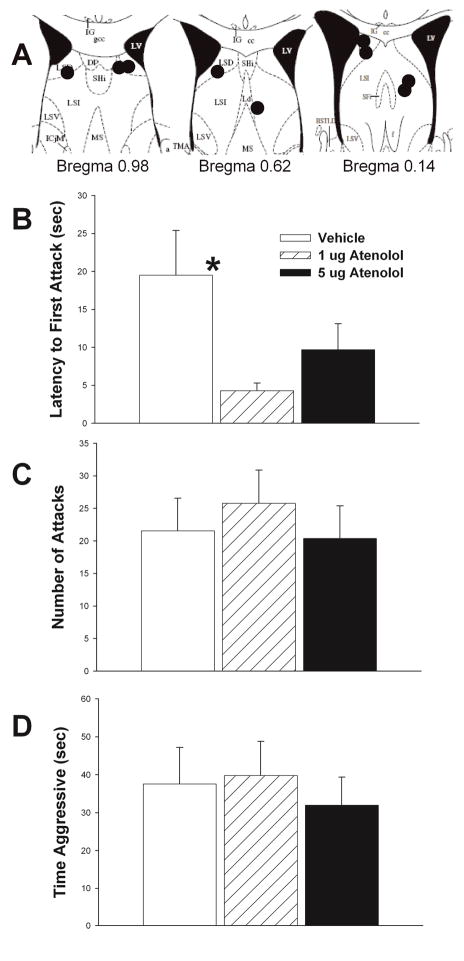

Figure 5.

Effects of β1 adrenergic receptor antagonist, atenolol, on maternal defense. A) Schematic representation of cannula hits (black circles) to LS (see Methods for further details). B) 1 μg atenolol significantly decreases latency to first attack relative to vehicle. No significant effects of either dose of atenolol relative to vehicle were found for either number of attacks (C) or total time aggressive (D) (see Results for further statistical details). Vehicle treatment results shown in white bars, 1 μg atenolol shown in hatched bars, and 5 μg of atenolol shown in black bars. N = 9, repeated measures testing. Bars indicate mean + SE. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05 between groups. Diagrams in A are adapted from Paxinos and Franklin, 2001(Paxinos and Franklin, 2001).

Pharmacological Treatment and Site-Directed Injections

Separate groups were used for evaluating (±) isoproterenol (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO), (−) propranolol (Sigma), and atenolol (Sigma). In the first experiment vehicle (saline), 10 μg, and 30 μg of isoproterenol was used. (±) Isoproterenol is a general β-adrenoceptor agonist and effectively agonizes both β1 and β2 receptor types. In the second experiment, vehicle (saline) and 2 μg of (−) propranolol, was used. (−) Propranolol is an active β-adrenoceptor blocking enantiamer that blocks both β1 and β2 receptors. In the third experiment, vehicle (saline), 1 μg, and 5μg of atenolol, were used. Atenolol is a specific β1 receptor antagonist. For all studies, a within subject repeated measures design was used. As such, each animal received vehicle and a given drug treatment. Order of injections was always counterbalanced. This approach was used because if there were any effect of multiple injections or multiple behavioral testing, then those effects would be equally distributed across treatments. Final N’s are provided below. Doses for the following were based on previous literature: propranolol (Gulia et al., 2002), isoproterenol (Zhang et al., 2001), and atenolol (Qu et al., 2008). Single injections were delivered each day for 2–3 consecutive days to animals under light isoflurane anesthesia. For the atenolol and isoproterenol studies, injections commenced on PPD 6. For the propranolol study, the onset of injections began between PPD 6 and PPD 10. In three cases of hits to LS, propranolol was injected following atenolol injections (with a one day washout period). The rationale for this approach is that previous studies have shown it is possible to accurately obtain different drug information from the same animal and this reduces the overall number of animals needed for a given study (Nephew and Bridges, 2008; Nephew et al., 2010). Light anesthesia was used because in earlier studies it was found that acute stress from handling and injection can reduce aggression and recent work has shown that mice exhibit reliable aggression despite brief exposure to isoflurane (D’Anna and Gammie, 2006, 2009; Gammie et al., 2004). Although it is possible there was some mild lingering effect of anesthesia on behavior or that the anesthesia triggered a stress response, this would apply to all doses and treatments. Unilateral injections (0.4 μL volume) were used because our prior work had shown these to be sufficient to alter maternal aggression (D’Anna and Gammie, 2009; Lee and Gammie, 2009). Also, unilateral injections produce less damage to tissue than bilateral injections. Based on previous studies and histological analysis of our brain sections following injection of Chicago sky blue dye (see below), it was expected that with each site-specific injection, that the fluid would diffuse ~ 200 μm from the injector tip and that there would be trend for some fluid to flow up the cannula (Lee and Gammie, 2009; Lohman et al., 2005; Nicholson, 1985). Infusions were verified by following movement of an air bubble in the tubing and the cannula remained in place for 120 seconds following each injection. 20 minutes after injection, a female was exposed to a 5-minute aggression test, a 5-minute light-dark box test, and a 2 min pup retrieval test.

Behavioral Testing

All behavioral testing occurred between 1400 and 1600 hours and testing commenced as early as PPD 6, but not later than PPD 11. In previous studies, we have found that maternal aggression and other maternal behaviors are expressed consistently across this time period (D’Anna and Gammie, 2006; D’Anna et al., 2005; Gammie et al., 2008). Each test session was video recorded. Each trial was subsequently analyzed to quantify maternal behaviors and anxiety-like behaviors by several individuals blind to testing conditions. Total behavioral testing lasted for 12 min. To maintain consistency among scorers, all scorers had to pass a calibration test just prior to scoring. Further, to ensure that any lingering rater bias was equally spread across each treatment, the same scorer always evaluated each mouse.

Maternal Defense Testing

Twenty minutes following injection, females were moved into the testing room, and the pups were separated from the dam. A male intruder was placed into the female’s cage for 5 minutes. Intruder mice from the same cage were used equally to test different treatments. Most interactions involved wrestling and chasing. Further, previous research has demonstrated that even when biting occurs in mice, it is superficial and remains confined to the fur (Litvin et al., 2007). For our procedures, if any mouse exhibited any sign of wounding, then the mouse would be immediately removed and treated. For this study, during the testing no wounding was observed. In three cases males initiated aggression towards the females and were quickly replaced by non-aggressive males. Removal of pups from the home cage of a dam before an aggression test does not diminish the expression of maternal aggression in mice (Svare et al., 1981). For quantification of maternal aggression, the following features were measured: latency to first attack, number of attacks, and total duration of attacks (Gammie and Nelson, 1999).

Light-Dark Box Testing and Pup Retrieval

After the intruder male was removed, the female was exposed to a light-dark box test for 5 minutes. The apparatus consisted of a large box (30 × 24.5 × 25.5 cm) with a black plastic box in one half with an opening to connect the dark compartment (~9.3 lux) to the light compartment (~250 lux). At the beginning of the test, the female was placed directly in front of the opening to the dark box. For quantification of light–dark box test the following features were measured: latency to enter the dark compartment, number of transitions between light and dark compartments, and total duration spent in the light and dark compartments (Bourin and Hascoet, 2003).

Immediately after the light-dark box test, the female was placed back into her home cage and her pups were scattered evenly around the cage. Each trial lasted two minutes. Pup retrieval was quantified by measuring the latency to retrieve the first and fourth pup.

Nissl Staining for Cannulae Placement

Following the last behavioral test and prior to brain collection, a 0.4 μL volume of 0.01% Chicago sky blue in saline was injected into the brain to verify cannula placement. Mice were anesthetized, decapitated and their brains were removed from the skull. Brains were postfixed overnight in 6% acrolein in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and stored in 30% sucrose in PBS for 2 days. Brains were frozen on a platform and cut into 40μm thick section using a sliding microtome (Leica, Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany) and stored in cryoprotectant solution at −20 °C until processing for Nissl staining with Thionin. Brain sections were mounted, stained with Thionin, cover slipped, and images of the section were projected from an Axioskop Zeiss light microscope through an Axiocam Zeiss high-resolution digital camera attached to the microscope and interfaced with a computer.

Statistical Analysis

All behavioral testing variables were analyzed using a one-way repeated measures (RM) analysis of variance (ANOVA) or a paired t-test of treatment versus control. In the cases where data were not normally distributed, natural log transformations were attempted. If transformations did not rectify normality violations, a non-parametric Friedman RM ANOVA on Ranks test was performed. For atenolol studies that hit LS, a small number of events were inadvertently not recorded and thus paired t-tests were used between each treatment (as opposed to repeated measures ANOVA) so that additional data would not be lost during analysis. In the case of latency to first attack, if an animal was not aggressive, a time of 300 seconds (the maximum time of the test) was assigned. Animals that showed 0 seconds of aggression for the control dose in the isoproterenol study were eliminated from analysis because the purpose of this study was to determine if this drug reduced aggression. Analyses were not run on latency to enter the dark portion of the light-dark apparatus for animals in the propranolol or atenolol studies because almost all animals at all doses tested had a latency of less than one second; thus data were non-normal and any p-values would have been equal to or just below 1.0. Additionally, due to camera malfunctions, pup retrieval data was not available for the propranolol study. The following indicate sites of cannula placement for the three studies. For the isoproterenol study, hits to LS, n = 11 (see Fig. 1A); misses, n = 9 (4 in ventricle, 1 in caudate putamen, 2 in ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and 2 in hippocampus). For the propranolol study, hits to LS, n = 8 (see Fig. 3A); misses, n = 10 (5 in ventricle, 1 in hippocampus, 1 in caudate putamen, 2 in medial preoptic nucleus, and 1 in triangular septal nucleus). For the atenolol study, hits to LS, n = 9 (see Fig. 5A); misses, n = 20 (5 in ventricle, 5 in caudate putamen, 3 in medial preoptic nucleus, 2 in bed nucleus of stria terminalis, 2 in triangular septal nucleus, 2 in thalamus, and 1 in cortex). For misses to caudate putamen and ventricles (N = 5 each), effects of treatment were analyzed for these locations. Further, all misses were combined and an additional analysis was performed. All statistics were run using PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

Effects of Isoproterenol on Maternal Defense and Pup Retrieval

There was no significant effect of isoproterenol treatment on latency to first attack (p = 0.227) (Fig. 1B). There was a main effect of treatment on total number of attacks (F 2,20 = 3.950, p = 0.036). Pairwise posthoc analysis revealed that 30 μg treatment significantly reduced number of attacks compared to vehicle (t = 2.571, df = 10, p = 0.028) (Fig. 1C). Additionally, there was a significant effect of treatment on the total amount of time females spent attacking intruder males (F2,20 = 5.330, p = 0.014) (Fig. 1D). 30 μg of isoproterenol significantly reduced time spent being aggressive compared to vehicle (t = −3.027, df = 10, p = 0.013). (Figure 3C). There was no significant difference in attack number between the 10 μg treatment and any of the other treatments. However, there was a trend for the 30 μg treatment to reduce total attack time relative to 10 μg (p = 0.061). There was no effect of treatment on aggressive behavior when the cannula did not hit LS (latency to attack, p = 0.323; number of attacks, p = 0.315; and total attack time, p = 0.154).

Intra-LS injections of isoproterenol did not affect the latency to retrieve either the first (p = 0.223) or the fourth pup (p = 0.189). There was no effect of treatment for latency to retrieve first (p = 0.779) or fourth (p = 0.549) pup in animals in which the LS was missed.

Effects of Isoproterenol on Light/Dark Box Performance

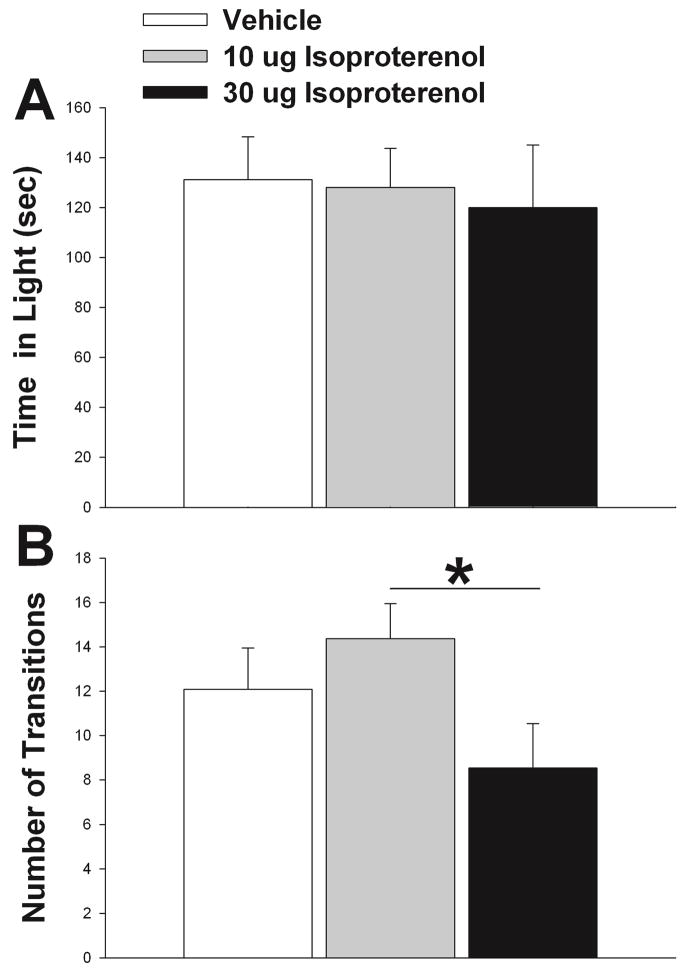

There was no significant effect of isoproterenol treatment on latency to enter the dark compartment of the light-dark box (p = 0.277) or total time spent in the open portion of the apparatus (p = 0.900) (Fig. 2A). However, there was a significant treatment effect on the number of transitions between the light and dark portions of the apparatus (F2,20 = 3.632, p = 0.045) (Fig. 2B). Posthoc analysis revealed that animals treated with 30 μg of isoproterenol made significantly fewer transitions than when they were treated with 10 μg (t = 2.698, p = 0.022). There was no effect of treatment on any behavior measured for the light-dark test when the cannula did not hit LS (latency to enter dark, p = 0.497; number of transitions, p = 0.340; and total time in light, p = 0.625).

Figure 2.

Effect of isoproterenol on light/dark box performance. (A) Isoproterenol did not alter time spent in the light portion of the box. (B) Number of transitions were higher in 10 μg isoproterenol relative to 30 μg, but no differences were found relative to control. Vehicle results shown in white bars and isoproterenol treatment shown in gray and black bars. N = 11, repeated measures testing. Bars indicate mean + SE. Asterisks indicate p < 0.05 between groups.

Effects of Propranolol on Maternal Defense

2 μg propranolol significantly decreased the latency to first attack relative to vehicle (t = 2.716, df = 7, p = 0.030) (Fig. 3B). There was no effect of propranolol treatment on the number of attacks relative to control (t = −1.287, df = 7, p = 0.239), although propranolol was associated with the higher number of attacks (Fig. 3C). Propranolol significantly increased the time a female spent attacking a male intruder (t = −2.664, df = 7, p = 0.032) (Fig. 3D). There was no effect of treatment on aggressive behavior when the cannula did not hit LS (time to first attack, p = 0.938; Total number of attacks, p = 0.238; and total time attacking, p = 0.226).

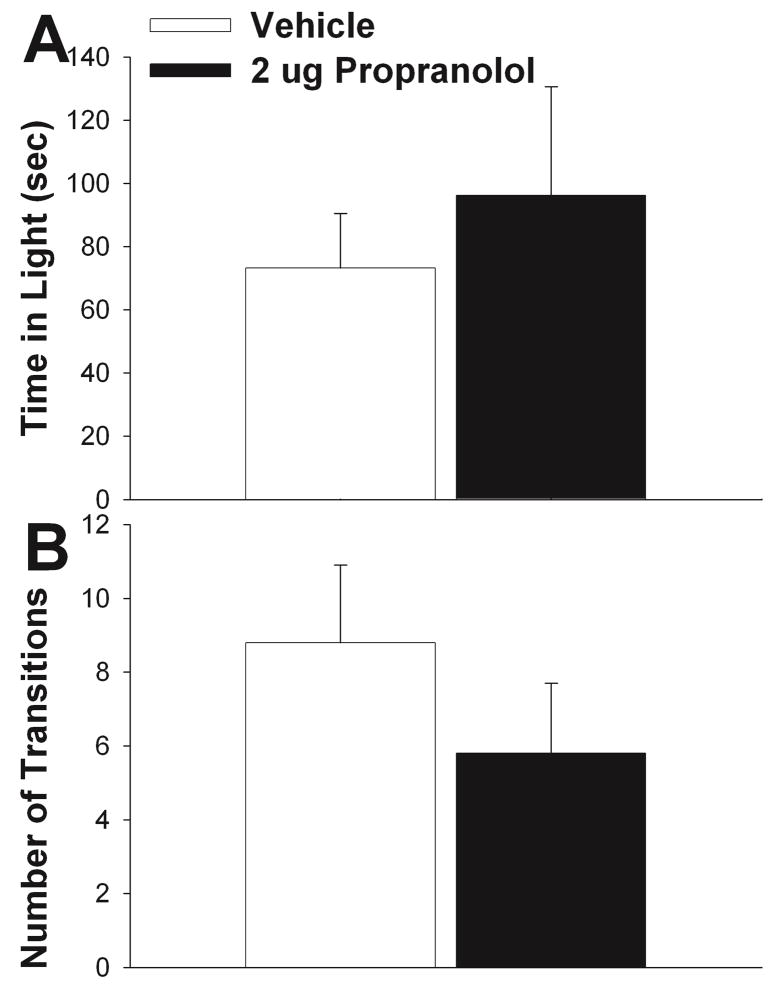

Effects of Propranolol on Light/Dark Box Performance

There was no significant effect of treatment on total time spent in the open portion of the apparatus (t = −0.697, df = 7, p = 0.509) (Fig. 4A) or the number of transitions between the light and dark portions of the apparatus (t = 1.845, df = 7, p = 0.108) (Fig. 4B). There was no effect of treatment on any behavior measured for the light-dark test when the cannula did not hit LS (time in open, p = 0.417; and number of transitions, p = 0.430).

Figure 4.

Effect of propranolol on light/dark box performance. Propranolol did not alter time spent in the light portion of the box (A) or number of transitions relative to control (B). Vehicle results shown in white bars and propranolol treatment shown in black bars. N = 8, repeated measures testing. Bars indicate mean + SE.

Effects of Atenolol on Maternal Defense

1 μg atenolol significantly reduced latency to first attack relative to vehicle (t = 2.89, df = 8, p = 0.020) (Fig. 5B). Although 5μg atenolol latency was shorter than for vehicle, significant differences were not found (t = 1.43, df = 6, p = 0.205) (Fig. 5B). Number of attacks and time aggressive by 1 μg atenolol relative to vehicle did not differ (t = −0.83, df = 8, p = 0.430, attack number) (t = −0.32, df = 6, p = 0.758, attack time) (Figs. 5C–D). Similarly, no effect of 5 μg atenolol relative to vehicle was found for number of attacks (p = 0.371) or time aggressive (p = 0.367, Signed Rank Test) (Figs. 5C–D). There was no effect of treatment on aggressive behavior when the cannula did not hit LS (latency to attack, RM ANOVA on ranks, p = 0.607; number of attacks, RM ANOVA on ranks p = 0.056; and total attack time, RM ANOVA on ranks p = 0.057). Caudate putamen and ventricle misses (N = 5 each) were analyzed separately and in each case treatment was not significant for latency to first attack (p = 0.445; p = 0.678 respectively), number of attacks (p = 0.158; p = 0.763 respectively), or total attack time (p = 0.196; p = 0.506 respectively)

Intra-LS injections of atenolol did not affect the latency to retrieve either the first (p = 0.644; vehicle versus 1 μg atenolol) (p = 0.398; vehicle versus 5 μg atenolol) or the fourth pup (p = 0.496; vehicle versus 1 μg atenolol) (p = 0.099; vehicle versus 5 μg atenolol). There was no effect of treatment for latency to retrieve first (p = 0.635; vehicle versus 1 μg atenolol) (p = 0.307; vehicle versus 5 μg atenolol) or the fourth pup (p = 0.372; vehicle versus 1 μg atenolol) (p = 0.697; vehicle versus 5 μg atenolol) in cases where LS was missed. Ventricle misses were also analyzed separately and in each case treatment was not significant for latency to retrieve first (p = 0.317, vehicle versus 1 μg; p = 0.083, vehicle versus 5 μg) or fourth pup (p = 0.360, vehicle versus 1 μg; p = 0.337, vehicle versus 5 μg). There were too many missing data points to analyze caudate putamen separately. None of the animals in which the caudate putamen was hit retrieved pups with in the 2-minute duration of the test. Data from these animals, therefore, could not be analyzed separately.

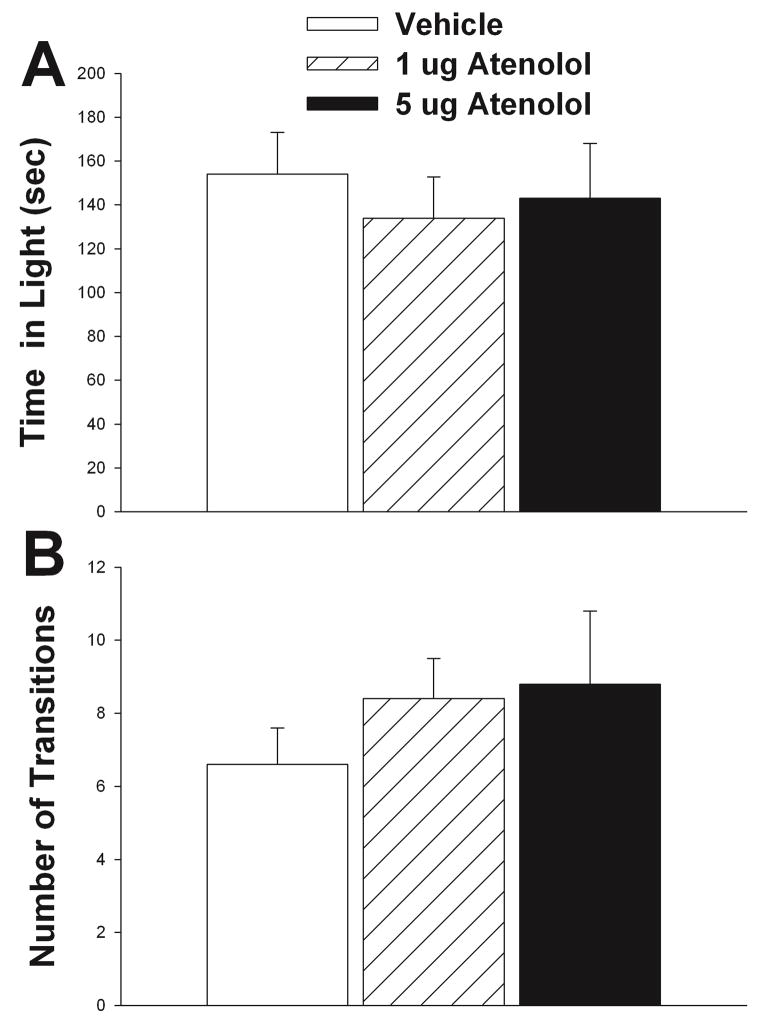

Effects of Atenolol on Light/Dark Box Performance

Neither 1 μg atenolol (t = 1.63, df = 8, p = 0.141) nor 5 μg atenolol (t = 0.42, df = 6, p = 0.686) had a significant effect on the total time spent in the light box relative to vehicle (Fig. 6A). Relative to vehicle, there was no significant effect of either 1 μg atenolol (t = 0.81, df = 8, p = 0.438) or 5 μg atenolol (t = −0.44, df = 6, p = 0.673) on the number of transitions between the light and dark portions of the apparatus (Fig. 6B). There was no effect of treatment on any behavior measured for the light-dark test when the cannula did not hit LS (number of transitions, p = 0.876; and total time in light, p = 0.071). Caudate putamen and ventricle misses were analyzed separately and treatment was not significant for number of transitions (p = 0.548; p = 0.627 respectively). Although treatment had no effect on total time spent in light (p = 0.946) for caudate putamen hits, there was a significant effect on ventricle hits (F2,8 = 6.41, p = 0.022). None of the pairwise comparisons were significant (vehicle versus 1μg p = 0.071; vehicle versus 5 μg p = 0.061), however in both cases it appears that there may be a trend for atenolol to reduce the amount of time individuals spent in the light.

Figure 6.

Effect of atenolol on light/dark box performance. Atenolol did not alter time spent in the light portion of the box or (A) or number of transitions (B). Vehicle treatment results shown in white bars, 1 μg atenolol shown in hatched bars, and 5μg of atenolol shown in black bars. N = 9, repeated measures testing. Bars indicate mean + SE.

Discussion

Maternal aggression is a critical and highly conserved component of maternal care in mammalian systems that involves dramatic shifts in a female’s behavioral response to certain social cues. For example, female mice are typically docile throughout most of their life history, but become aggressive toward intruders when lactating (Gammie, 2005; Gammie and Lonstein, 2006). The purpose of the current work was to investigate the possibility that changes in NE signaling in the LS is a mechanism that facilitates this increase in aggression during lactation.

To test the hypothesis that reduced NE signaling in LS facilitates maternal aggression, we performed two experiments using site directed injections to the LS. In our first experiment, we asked whether enhancing NE signaling (via β adrenergic receptors) in LS would decrease maternal aggression. Using the β adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol, we hypothesized that agonizing β receptors would suppress aggression and this is what we found. 30 μg of isoproterenol significantly decreased the total number of attacks initiated by the females (Fig. 1C) and significantly decreased total time females spent being aggressive (Fig. 1D) relative to vehicle. Although not significant, isoproterenol treatment also increased latency to attack relative to control. Importantly, these effects were only found in animals where the cannula hit LS. The lack of effect of treatment pup on pup retrieval, an active motor behavior, suggests that isoproterenol did not impair aggression via non-specific mechanisms. One shortcoming of this study is that we did not evaluate other maternal behaviors and we cannot exclude the possibility that alterations of NE signaling would have affected some other maternal measures. Together, these findings suggest that elevated NE acting on β adrenergic receptors is a mechanism for suppressing maternal defense, but the actions on additional maternal behaviors are not known.

In the second and third experiments we injected the non-specific β-adrenergic receptor antagonist, propranolol, and the specific β1 receptor antagonist, atenolol, and predicted that injections of these drugs would increase maternal aggression. Our results support this hypothesis as intra-LS injections of propranolol, which blocks the action of NE, significantly decreased the latency to attack an intruder (Fig. 3B) and significantly increased total time spent aggressive (Fig. 3D). The 1 μg dose of atenolol in LS significantly decreased latency to attack. Again, the effects of the antagonists were only observed in animals in which the cannula hit LS. Together, these results suggest reductions in NE signaling acting on the β adrenergic receptors is a mechanism by which maternal defense can emerge. However, these results do not preclude the possibility that NE acting at other regions also influences maternal defense.

For neither the agonist nor the antagonist that altered aggression, was the effect on light/dark box behavior profound. Behavior in the light-dark apparatus was not affected by isoproterenol treatment, except in the number of transitions made between the dark and light sections of the light-dark box. Here 30 μg of isoproterenol reduced the number of transitions made relative to 10 μg treatment, but not relative to control (Fig. 2B). Neither propranolol nor atenolol altered performance in the light-dark box apparatus (Figs. 4A–B). There was a trend for atenolol in the ventricles to decrease time in light, but levels did not reach significance in posthoc tests. Acute peripheral injection of propranolol increases transitions in the light-dark test (Gao and Cutler, 1992), but our lack of effect here is likely due to differing site of action or level of treatment. The results from agonist and antagonist indicate that maternal defense and anxiety-like behaviors are not necessarily linked in LS under these test conditions. The general lack of effect of treatment on light-dark performance for both agonist and antagonist supports the idea that effects on aggression did not occur via non-specific mechanisms. However, monitoring of general activity following the different treatments would be needed to rule out other non-specific locomotor effects.

Propranolol acts as a both a β1 and β2 antagonist, but it also can affect other signaling pathways (i.e., serotonin receptor antagonist) (Audi et al., 1990; Maura et al., 1987; Middlemiss, 1984). Although we cannot exclude a non-adrenergic receptor effect of propranolol, this is less likely given that the β1 specific antagonist, atenolol (1 μg) significantly decreased latency to attack. Additional measures of aggression were not found to be altered, but this is not necessarily surprising given that inhibition of β1 alone would not be expected to act as effectively as when both receptor are inhibited. The atenolol finding provides additional support for the pharmacological results derived from using propranolol because this drug does not affect the serotonergic system. Further studies will continue to investigate the relative importance of β1 versus β2 receptors in the mediation of maternal aggression. Although chronic propranolol treatment increases β-adrenergic receptor number in the cerebral cortex (Hegstrand and Eichelman, 1983), in this study we only used a single propranolol treatment, so increases in aggression would not be expected to result from propranolol-induced changes in β adrenoreceptor numbers.

The location of the injections within LS differs to some extent between the studies (e.g., the hits in the propranolol study are more rostral than that in the isoproterenol study) and we cannot be sure whether effects of either treatment would be equal across LS regions. Future studies are needed to determine if the different anatomical regions of LS respond similarly to treatment and whether certain regions are more critical in regulating the change in aggressive behaviors that occur in lactating females. It is also important to consider that some researchers hypothesize that pharmacological manipulations that are aimed at particular noradrenergic sites may have general neuronal effects across the central nervous system, due to the modulation of mainly non-synaptic communication (Haller et al., 1998). This hypothesis suggests that it is these general effects that mediate the behavioral responses to β-adrenergic manipulation. In all experiments, however, only in individuals in which the LS was injected were behavioral changes observed. Neither propranolol, isoproterenol, nor atenolol affected behavior when it was injected in to other brain regions (although there was a trend for atenolol in some cases), suggesting that the effects observed are specific to the LS. However, because the misses were spread across multiple regions, there are limitations in concluding that only LS can mediate the actions. Additional injections to adjacent regions can further clarify how a region is linked to an action.

An important unanswered question is what are the downstream pathways by which NE acts in LS to regulate maternal defense. LS projects to a number of brain regions that have been implicated in maternal aggression, including central amygdala and periaqueductal gray (Bosch et al., 2005; Lee and Gammie, 2010; Lonstein et al., 1998; Risold and Swanson, 1997; Sheehan et al., 2004). Thus, LS could simply act by modulating an underlying aggression circuitry. However, LS could also modulate defense by modulating sympathetic nervous system output. For example, chemical stimulation of LS alters arterial pressure (Gelsema and Calaresu, 1987). Further, LS projects directly and indirectly (via medial preoptic nucleus) to paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the indirect connection to PVN has been linked to sympathetic regulation via tract tracing studies (Westerhaus and Loewy, 1999). PVN is strongly linked to sympathetic modulation (Pyner, 2009) and centrally released NE is part of this pathway (Zhang and Felder, 2008). Vasopressin from PVN can modulate sympathetic output via central actions (Kc et al., 2010), but vasopressin is also released to the periphery from PVN via the pituitary and this peripheral release of vasopressin can also regulate cardiovascular tone (Nephew et al., 2005a; Nephew et al., 2005b). Vasopressin has recently been linked to maternal aggression (Nephew and Bridges, 2008; Nephew et al., 2010) and it is possible that our alterations of NE action in LS is regulating maternal aggression via changes in outputs from PVN that include vasopressin signaling. Additional studies need to address which are the critical pathways by which LS regulates offspring protection.

In this study, we used mice previously selected for high maternal defense. Our rationale was that these mice provide a reliable baseline to examine increases or decreases in aggression. Also, males show normal aggression and these females only exhibit reliable aggression during the postpartum period, indicating they do not represent merely a strain with heightened aggression. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that results derived from this strain do not necessarily apply to other mouse strains. Thus, evaluation of the findings in other strains will be important in progressing this line of research.

The results of these three experiments indicate a role of NE signaling in LS in the expression of maternal aggression in lactating females. These data support the hypothesis that reductions in NE signaling in LS region may be instrumental to the development of heightened aggression in lactating females. However, these data do not support the idea that reductions in anxiety or the fear response also occur as a result of altered NE signaling on β adrenergic receptors in this brain region, at least not in the tests employed here. Overall, these data, give further insight into the understanding of how the maternal defense circuitry works. Such work may aid in providing information about the neurological and emotional changes, including mental health disorders, which occur during the postpartum period.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dan Kula, Tyler Wied, Kristen Labs, Alexandra Ostromecki, and Dan Latus for their assistance in running and scoring behavioral trials. We would also like to thank Sharon A. Stevenson for her technical support. This research was funded by a NIH grant R01 MH085642 to S.C.G. and a Department of Zoology Guyer Postdoctoral Fellowship to M.L.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/bne

References

- Audi EA, Deoliveira RMW, Deoliveira CE, Graeff FG. Stereoselectivity of the anxiolytic effect of propranolol microinjected into the dorsal midbrain central gray. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 1990;23(10):985–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi CO, Barrera G, Lapiz MD, Bedard T, Mahan A, Morilak DA. Noradrenergic facilitation of shock-probe defensive burying in lateral septum of rats, and modulation by chronic treatment with desipramine. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2007;31(2):482–495. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch OJ, Kromer SA, Brunton PJ, Neumann ID. Release of oxytocin in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, but not central amygdala or lateral septum in lactating residents and virgin intruders during maternal defence. Neuroscience. 2004;124(2):439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch OJ, Meddle SL, Beiderbeck DI, Douglas AJ, Neumann ID. Brain oxytocin correlates with maternal aggression: link to anxiety. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:6807–6815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1342-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourin M, Hascoet M. The mouse light/dark box test. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;463(1–3):55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette B, Poulain P, Beauvillain JC. Noradrenaline modulates GABA-mediated synaptic transmission in neurones of the mediolateral part of the guinea pig lateral septum via local circuits. Neuroscience Research. 2001;39(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna KD, Gammie SC. Hypocretin-1 dose-dependently modulates maternal behaviour in mice. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2006;18:553–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna KD, Gammie SC. Activation of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2 in lateral septum negatively regulates maternal defense. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009 doi: 10.1037/a0014987. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna KD, Stevenson SA, Gammie SC. Urocortin 1 and 3 impair maternal defense behavior in mice. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119:161–171. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.4.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannelly KJ, Kemble ED, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. Effects of septal-forebrain lesions on maternal aggression and maternal care. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1986;45(1):17–30. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(86)80002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammie SC. Current models and future directions for understanding the neural circuitries of maternal behaviors in rodents. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2005;4:119–135. doi: 10.1177/1534582305281086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammie SC, Garland T, Stevenson SA. Artificial selection for increased maternal defense behavior in mice. Behavior Genetics. 2006;36:713–722. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9071-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammie SC, Lonstein JS. Maternal Aggression. In: Nelson RJ, editor. Biology of Aggression. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gammie SC, Negron A, Newman SM, Rhodes JS. Corticotropin-releasing factor inhibits maternal aggression in mice. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118:805–814. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.4.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammie SC, Nelson RJ. Maternal aggression is reduced in neuronal nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:8027–8035. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-08027.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammie SC, Seasholtz AF, Stevenson SA. Deletion of corticotropin-releasing factor binding protein selectively impairs maternal, but not intermale aggression. Neuroscience. 2008;157(3):502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Cutler MG. Effects of acute and subchronic administration of propranolol on the social behaviour of mice; an ethopharmacological study. Neuropharmacology. 1992;31(8):749–756. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(92)90036-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelsema AJ, Calaresu FR. Chemical microstimulation of the septal area lowers arterial-pressure in the rat. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;252(4):R760–R767. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.4.R760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulia KK, Kumar VM, Mallick HN. Role of the lateral septal noradrenergic system in the elaboration of male sexual behavior in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;72(4):817–823. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00771-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haden SC, Scarpa A. The noradrenergic system and its involvement in aggressive behaviors. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2007;12(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Kruk MR. Neuroendocrine stress response and aggression. In: Mattson MP, editor. Neurobiology of Aggression. Totawa: Humana Press; 2003. pp. 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Makara GB, Kruk MR. Catecholaminergic involvement in the control of aggression: hormones, the peripheral sympathetic, and central noradrenergic systems. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1998;22(1):85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegstrand LR, Eichelman B. Increased shock-induced fighting with super-sensitive beta-adrenergic receptors. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1983;19(2):313–320. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kc P, Balan KV, Tjoe SS, Martin RJ, LaManna JC, Haxhiu MA, et al. Increased vasopressin transmission from the paraventricular nucleus to the rostral medulla augments cardiorespiratory outflow in chronic intermittent hypoxia-conditioned rats. Journal of Physiology-London. 2010;588(4):725–740. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.184580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Gammie SC. GABA enhancement of maternal defense in mice: Possible neural correlates. Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior. 2007;86:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Gammie SC. GABA(A) receptor signaling in the lateral septum regulates maternal aggression in mice. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;123(6):1169–1177. doi: 10.1037/a0017535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Gammie SC. GABA(A) receptor signaling in caudal periaqueductal gray regulates maternal aggression and maternal care in mice. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;213(2):230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightman SL. Alterations in hypothalamic-pituitary responsiveness during lactation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1992;652:340–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb34365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Stenevi U. Dopamine and noradrenaline neurons projecting to the septal area in the rat. Cell and Tissue Research. 1978;190(3):383–407. doi: 10.1007/BF00219554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvin Y, Blanchard DC, Pentkowski NS, Blanchard RJ. A pinch or a lesion: A reconceptualization of biting consequences in mice. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33(6):545–551. doi: 10.1002/ab.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Alreja M. Norepinephrine inhibits neurons of the intermediate subnucleus of the lateral septum via alpha2-adrenoceptors. Brain Research. 1998;806(1):36–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Curtis JT, Wang Z. Vasopressin in the lateral septum regulates pair bond formation in male prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;115(4):910–919. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman RJ, Liu LG, Morris M, O’Brien TJ. Validation of a method for localised microinjection of drugs into thalamic subregions in rats for epilepsy pharmacological studies. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2005;146(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonstein JS, Gammie SC. Sensory, hormonal, and neural control of maternal aggression in laboratory rodents. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2002;26:869–888. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonstein JS, Simmons DA, Stern JM. Functions of the caudal periaqueductal gray in lactating rats: kyphosis, lordosis, maternal aggression, and fearfulness. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1998;112(6):1502–1518. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.6.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matray-Devoti J, Wagner GC. Propranolol-induced increases in target-biting attack. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1993;46(4):923–925. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90223-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maura G, Ulivi M, Raiteri M. (−)-Propranolol and (+/−)-cyanopindolol are mixed agonists antagonists at serotonin autoreceptors in the hippocampus of the rat-brain. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26(7A):713–717. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlemiss DN. Stereoselective blockade at [H-3]5-Ht binding-sites and at the 5-Ht autoreceptor by propranolol. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1984;101(3–4):289–293. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nephew BC, Aaron RS, Romero LM. Effects of arginine vasotocin (AVT) on the behavioral, cardiovascular, and corticosterone responses of starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) to crowding. Hormones and Behavior. 2005a;47(3):280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nephew BC, Bridges RS. Central actions of arginine vasopressin and a V1a receptor antagonist on maternal aggression, maternal behavior, and grooming in lactating rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior. 2008;91(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nephew BC, Byrnes EM, Bridges RS. Vasopressin mediates enhanced offspring protection in multiparous rats. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(1):102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nephew BC, Reed LM, Romero LM. A potential cardiovascular mechanism for the behavioral effects of central and peripheral arginine vasotocin. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2005b;144(2):156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann ID, Johnstone HA, Hatzinger M, Liebsch G, Shipston M, Russell JA, et al. Attenuated neuroendocrine responses to emotional and physical stressors in pregnant rats involve adenohypophysial changes. Journal of Physiology. 1998;508(Pt 1):289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.289br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson C. Diffusion from an injected volume of a substance in brain-tissue with arbitrary volume fraction and tortuosity. Brain Research. 1985;333(2):325–329. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91586-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pyner S. Neurochemistry of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: Implications for cardiovascular regulation. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2009;38(3):197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu LL, Guo NN, Li BM. beta 1-and beta 2-Adrenoceptors in basolateral nucleus of amygdala and their roles in consolidation of fear memory in rats. Hippocampus. 2008;18(11):1131–1139. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi GA, Hansen S, Sodersten P. Offspring control of cerebrospinal fluid GABA concentrations in lactating rats. Neuroscience Letters. 1987;75(1):85–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainbow TC, Parsons B, Wolfe BB. Quantitative autoradiography of beta 1- and beta 2-adrenergic receptors in rat brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81(5):1585–1589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risold PY, Swanson LW. Connections of the rat lateral septal complex. Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 1997;24(2–3):115–195. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan TP, Chambers RA, Russell DS. Regulation of affect by the lateral septum: implications for neuropsychiatry. Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 2004;46(1):71–117. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson CA, Gordon M. Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine on shock-elicited aggression, emotionality and maternal behavior in female rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1975;3(3):331–335. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(75)90039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svare B, Betteridge C, Katz D, Samuels O. Some situational and experiential determinants of maternal aggression in mice. Physiology & Behavior. 1981;26(2):253–258. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toufexis DJ, Rochford J, Walker CD. Lactation-induced reduction in rats’ acoustic startle is associated with changes in noradrenergic neurotransmission. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1999;113(1):176–184. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toufexis DJ, Thrivikraman KV, Plotsky PM, Morilak DA, Huang N, Walker CD. Reduced noradrenergic tone to the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus contributes to the stress hyporesponsiveness of lactation. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 1998;10(6):417–427. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toufexis DJ, Walker CD. Noradrenergic facilitation of the adrenocorticotropin response to stress is absent during lactation in the rat. Brain Research. 1996;737(1–2):71–77. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker CD, Tilders FJ, Burlet A. Increased colocalization of corticotropin-releasing factor and arginine vasopressin in paraventricular neurones of the hypothalamus in lactating rats: evidence from immunotargeted lesions and immunohistochemistry. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2001;13(1):74–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhaus MJ, Loewy AD. Sympathetic-related neurons in the preoptic region of the rat identified by viral transneuronal labeling. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1999;414(3):361–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowska-Lupina I, Ossowska G, Lupina T, Klenk-Majewska B. Prolonged treatment with beta-adrenoceptor antagonists counteracts the aggression deficit induced by chronic stress. Polish Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;49(5):283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HT, Frith SA, Wilkins J, O’Donnell JM. Comparison of the effects of isoproterenol administered into the hippocampus, frontal cortex, or amygdala on behavior of rats maintained by differential reinforcement of low response rate. Psychopharmacology. 2001;159(1):89–97. doi: 10.1007/s002130100889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZH, Felder RB. Hypothalamic corticotrophin-releasing factor and norepinephrine mediate sympathetic and cardiovascular responses to acute intracarotid injection of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in the rat. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2008;20(8):978–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]