Abstract

Recent analyses suggest the decline in coronary heart disease mortality rates is slowing in younger age groups in countries such as the US and the UK. This work aimed to analyse recent trends in cardiovascular mortality rates in the Netherlands. Analysis was of annual all circulatory, ischaemic heart disease (IHD), and cerebrovascular disease mortality rates between 1980 and 2009 for the Netherlands. Data were stratified by sex and 10-year age group (age 35–85+). The annual rate of change and significant changes in the trend were identified using joinpoint Poisson regression. For almost all age and sex groups examined the rate of IHD and cerebrovascular disease mortality in the Netherlands has more than halved between 1980 and 2009. The decline in mortality from both IHD and cerebrovascular disease is continuing for all ages and sex groups, with anacceleration in the decline apparent from the late 1990s/early 2000s. The decline in age-specific all circulatory, coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease mortality rates continues for all age and sex groups in the Netherlands.

Keywords: Mortality rate, Netherlands, Trends, Cardiovascular disease, Coronary heart disease

The decline in age-standardised cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rates has continued since the 1960s in the developed world [1]. In the USA, rates declined from around 830/100,000 population in 1960 to around 380/100,000 population in 1997 [1]. There appeared to be a slowing of the decline in age-standardised cardiovascular and coronary heart disease mortality rates in the USA between 1990 and 1997. However, more recent publications suggest the decline in age-standardised coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality rates has continued since 1997 in countries such as the USA, UK and Australia, and has in fact accelerated in recent years [2, 3].

In the past 2 years there have been reports of a slowing of the decline in CHD mortality rates at younger ages in developed countries [2–4]. Detailed reports from the UK and USA, have both demonstrated that in those aged under 55 years, CHD mortality rates have stopped decreasing, and even increased, for the first time in over two decades.

To date there have been no analyses of trends in coronary heart disease mortality rates at younger ages in non-Anglo Saxon countries. Here we analysed trends in age-specific cardiovascular mortality rates, and its major subtypes—ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease—in the Netherlands between 1980 and 2009.

Methods

Data

National mortality rates were obtained for 10 year age groups from age 35 to 84 years between 1980 and 2009 for all circulatory disease (ICD-9 codes 390-459 & ICD-10 codes I00-I99), ischaemic heart disease (ICD-9 codes 410-414 & ICD-10 I20-I25) and cerebrovascular disease (ICD-9 codes 430-438 & ICD-10 codes I60-I69). Numbers of deaths and population counts (source: CBS Statline) were used to calculate annual mortality rates.

A joinpoint Poisson regression provided the estimated annual percentage change and detected points in time at which significant changes in the trends occurred (Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 3.4.2. October 2009; Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute). The joinpoint permutation test was used to select the most parsimonious model that best fitted the data. A maximum of three joinpoints was allowed for estimations. For each annual percentage change estimate, the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated [5].

A secondary analysis was also performed for comparison, using Poisson regression to analyse the annual rate of change within each 5 year period between 1980 and 2009.

Results

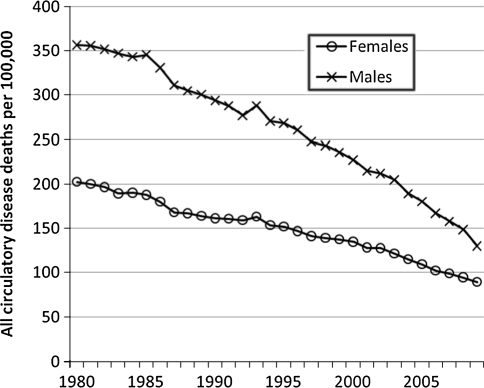

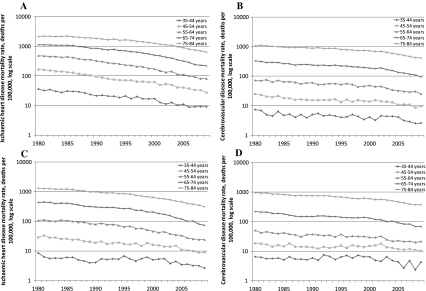

The age-standardised rate of all circulatory disease mortality has declined since 1980 in the Netherlands (Fig. 1), from 357 per 100,000 to 130 per 100,000 in 2009 for males and from 202 per 100,000 to 89 per 100,000 in 2009 for females. Large decreases in ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease mortality rates were observed for all age groups between 1980 and 2009 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Age-standardised all circulatory disease mortality rates (standardised to the World Health Organisation World Standard). Crosses represent males and circles represent females

Fig. 2.

Observed mortality rates in the Netherlands between 1980 and 2009 for each 10 year age group between 35 and 85 years (per 100,000, log scale). a Ischaemic heart disease mortality, males, b Ischaemic heart disease mortality, females, c Cerebrovascular disease mortality, males, d Cerebrovascular disease mortality, females

All circulatory disease mortality rates declined between 1980 and 2009 for all age and sex groups, with the rate of decline accelerating over time in all groups (data not shown).

Joinpoint analysis of ischaemic heart disease mortality rates demonstrated similar trends (Table 1a). For males and females in all age groups, an acceleration in the mortality rate decline has been observed since the late 1990s/early 2000s. For some groups this represents a continually increasing improvement in the mortality rates since 1980 (males 35–44, 55–64, 65–74, and 75–85, and females 45–54, 55–64, 65–74 and 75–84). For males aged 45–54 and females aged 35–44 this acceleration follows a period of slowing of improvements in the mortality rate decline in the 1990s.

Table 1.

Annual change in rate of (A) ischaemic heart disease mortality, and (B) cerebrovascular disease mortality between 1980 and 2009

| Period I | Period II | Period III | Period IV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | Rate change | Years | Rate change | Years | Rate change | Years | Rate change | ||

| (A) | |||||||||

| Males | 35–44 | 1980–1998 | −4.0 (−4.3, −3.6) | 1998–2009 | −6.6 (−8.3, −4.0) | ||||

| 45–54 | 1980–1986 | −4.1 (−5.5, −2.7) | 1986–1993 | −7.4 (−8.9, −5.8) | 1993–2000 | −3.3 (−5.0, −1.5) | 2000–2009 | −7.7 (−8.9, −6.6) | |

| 55–64 | 1980–1985 | −1.8 (−3.2, −0.3) | 1985–1998 | −5.9 (−6.3, −5.4) | 1998–2009 | −8.1 (−8.8, −7.4) | |||

| 65–74 | 1980–1985 | −0.8 (−2.2, 0.7) | 1985–1999 | −4.4 (−4.8, −4.0) | 1999–2009 | −9.4 (−10.2, −8.7) | |||

| 75–84 | 1980–1985 | −0.4 (−1.7, 1.0) | 1985–1996 | −2.9 (−3.4, −2.4) | 1996–2003 | −5.2 (−6.3, −4.1) | 2003–2009 | −8.4 (−9.6, −7.1) | |

| Females | 35–44 | 1980–1989 | −4.9 (−8, −1.8) | 1989–1999 | 2.7 (−0.5, 6.1) | 1999–2009 | −7.4 (−10.1, −4.6) | ||

| 45–54 | 1980–2004 | −3.3 (−2.7, −2.9) | 2004–2009 | −9.2 (−14.5, −3.6) | |||||

| 55–64 | 1980–1984 | 0.1 (−3.4, 3.7) | 1984–1996 | −3.9 (−4.7, −3.2) | 1996–2009 | −7.9 (−8.7, −7.1) | |||

| 65–74 | 1980–2000 | −3.7 (−4.0, −3.4) | 2000–2009 | −11.1 (−12.6, −9.7) | |||||

| 75–84 | 1980–1985 | −1.8 (−3.2, 0.5) | 1985–1996 | −3.5 (−4.0, −3.0) | 1996–2003 | −5.7 (−6.8, −4.5) | 2003–2009 | −8.5 (−9.9, −7.0) | |

| (B) | |||||||||

| Males | 35–44 | 1980–1982 | −17.6 (−41.1, 15.4) | 1982–2005 | −1.2 (−2.1, −0.3) | 2005–2009 | −12.3 (−23.8, 0.9) | ||

| 45–54 | 1980–1987 | −5.7 (−7.9, −3.3) | 1987–2002 | −0.9 (−1.7, 0) | 2002–2009 | −6.4 (−8.8, −3.8) | |||

| 55–64 | 1980–2001 | −2.3 (−2.7, −1.8) | 2001–2009 | −6.9 (−8.9, −4.9) | |||||

| 65–74 | 1980–1987 | −4.0 (−4.7, −3.3) | 1987–1994 | −1.0 (−2.0, 0) | 1994–2002 | −2.9 (−3.7, −2.1) | 2002–2009 | 8.5 (−9.4, −7.6) | |

| 75–84 | 1980–2002 | −2.0 (−2.2, −1.9) | 2002–2009 | −7.6 (−8.7, −6.4) | |||||

| Females | 35–44 | 1980–1999 | 0.8 (−0.6, 2.2) | 1999–2009 | −6.1 (−9.7, −2.2) | ||||

| 45–54 | 1980–1991 | −2.8 (−4.2, −1.3) | 1991–2002 | 1.6 (0, 3.2) | 2002–2009 | −6.5 (−9.0, −3.8) | |||

| 55–64 | 1980–2001 | −2.1 (−2.6, −1.5) | 2001–2009 | 4.9 (−7.4, −2.3) | |||||

| 65–74 | 1980–1987 | −4.8 (−5.9, −3.6) | 1987–2000 | −1.3 (−1.9, −0.8) | 2000–2009 | −7.2 (−8.2, −6.1) | |||

| 75–84 | 1980–1987 | −3.2 (−4.2, −2.2) | 1987–1992 | −0.5 (−2.9, 1.9) | 1992–2003 | −3.0 (−3.6, −2.4) | 2003–2009 | −6.6 (−8.1, −5.2) | |

The annual change in rate in each period is significantly different from the preceding period, as determined by joinpoint analysis

Joinpoint analysis of cerebrovascular disease mortality rates demonstrated improvements in mortality rates in the most recent time period in all age and sex groups examined, following a slowing in the rate of decline in the late 1980s/early 1990s for males aged 45–54 and 65–74 and females aged 45–54, 65–74 and 75–84 (Table 1b).

Analyses were also performed of mortality rates within consecutive 5 year periods, and using 5-year age groups (data not shown). The conclusions were unchanged—with all analyses demonstrating a greater rate of mortality improvement in the most recent period analysed.

Discussion

This detailed analysis of cardiovascular mortality rates between 1980 and 2009 demonstrates that in the Netherlands all age and sex groups have experienced improvements in all circulatory disease, IHD and cerebrovascular mortality in recent times. There was no evidence of a slowing in the IHD mortality rate decline for those aged under 55 years.

Whilst the quality of the mortality data collection in countries such as the Netherlands is generally high, coding of death certificates has some problems, due primarily to the number of ill-defined cardiovascular codes. This can mean that comparisons between countries, and over time, may not be counting the same causes of death as different practitioners may assign the same cause of death to different codes. This is particularly important at older ages, but less likely at younger ages. An analysis of this phenomenon by the World Health Organisation suggested that miscoding was minimal in the Netherlands [6]. In addition, our analyses of all circulatory disease mortality demonstrated the same broad trends as those for IHD and cerebrovascular disease. Another potential cause of coding inaccuracies is the change from ICD-9 to ICD-10. However, an analysis of coding discontinuities demonstrated no significant discontinuities for this transition for the major circulatory disease sub-types in the Netherlands [7]. Whilst some of the apparent changes in trends may be due to artefact, this is unlikely to affect the general conclusion that for all age and sex groups, all circulatory disease, IHD and cerebrovascular disease mortality rates are continuing to decline in the Netherlands.

In almost all age and sex groups the rate of decline in IHD mortality accelerated in the late 1990s to early 2000s. This is consistent with what has been observed for age-standardised mortality rates in a number of other countries, including England, Wales and Scotland [3, 4] and the US [2]. However, in contrast to the Netherlands, in England, Wales, Scotland and the US the rate of decline in those aged under 55 years of age slowed in the most recent period.

In the US the deceleration commenced in 1989, with further deceleration observed in 2000 [2]. In England, Wales and Scotland the decelerations commenced slightly later, between 1994 and 2003 [3, 4]. Interestingly, in the current analysis Dutch males aged 45–54 years also experienced a deceleration in the IHD mortality rate decline from 1993, but this was then followed by improved mortality from 2000. Similarly, Dutch females aged 35–44 experienced an increase in the IHD mortality rate decline from 1989, but this was then followed by improved mortality from 1999.

It will be important to identify whether or not these observed differences in trends between the Netherlands and countries such as the US and UK represent a specific difference in the causes or treatment of circulatory disease. The observed acceleration in the circulatory disease mortality rate decline since the late 1990s may reflect broader changes in the healthcare system in the Netherlands, as since 2002 a general acceleration in all cause mortality, and in particular mortality due to symptoms and ill-defined conditions, has been observed [8, 9]. A recent analysis of these trends suggests that this is due to general improvements in health care services [9]. It will be important to explore whether improvement of primary and secondary prevention of CHD in countries such as the UK and US would lead to the continued improvements in CHD mortality in all adults observed in the Netherlands.

Alternatively, the current analysis may provide some support for the hypothesis that the observed flattening of the CHD mortality rate in those under age 55 in countries such as the US and UK reflects increased prevalence of obesity and diabetes [3, 10, 11]. The Netherlands has a markedly lower prevalence of adult obesity than countries such as the UK and US, has experienced lower absolute increases in obesity over the past decade [12–14] and consequently has a lower prevalence of diabetes in adults [15]. It will be important to continue to monitor trends in the Netherlands to see whether the mortality rate decline in younger adults continues.

In conclusion, all circulatory, IHD and cerebrovascular disease mortality rates are continuing to improve in the Netherlands in all age and sex groups. This is in contrast to trends in those aged under 55 years of age observed in an increasing number of countries. It will be critical to continue to monitor these trends in the Netherlands, and to elucidate the reason for their apparent divergence with countries such as the US and the UK.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Haider Mannan, Alison Beauchamp, Helen Walls, Rosanne Freak-Poli and Linton Harriss for constructive comments. This work was supported by VicHealth (AP), the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia (Health Services Research Grant 465130, CS), The University of Washington Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center funded by NIH NIDDK grant P30 DK-17047 (EB), and NETSPAR (WN).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Cooper R, Cutler J, Desvigne-Nickens P, Fortmann S, Friedman L, Havlik R, Hogelin G, Marler J, McGovern P, Morosco G, Mosca L, Pearson T, Stamler J, Stryer D, Thom T. Trends and disparities in coronary heart disease, stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases in the United States. Circulation. 2000;102:3137–3147. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the US from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(22):2128–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Flaherty M, Ford E, Allender S, Scarborough P, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease trends in England and Wales from 1984 to 2004: concealed levelling of mortality rates among young adults. Heart. 2008;94(2):178–181. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.118323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Flaherty M, Bishop J, Redpath A, McLaughlin T, Murphy D, Chalmers J, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in Scotland in relation to social inequalities: time trend study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2613. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::AID-SIM336>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lozano R, Murray CJL, Lopez AD, Satoh T. Miscoding and misclassification of ischaemic heart disease mortality. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen F, Kunst AE. ICD coding changes and discontinuities in trends in cause-specific mortality in six European countries, 1950–99. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(12):904–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garssen J. van der Meulen A. Overlijdensrisico’s naar herkomstgroep: daling en afnemende verschillen. Bevolkingstrends. 2007;55(4):56–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackenbach JP, Garssen J. Renewed progress in life expectancy: the case of the Netherlands. National Academy of Sciences, Washington In press.

- 10.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Giles WH, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(23):2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, Layden J, Carnes BA, Brody J, Hayflick L, Butler RN, Allison DB, Ludwig DS. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60(7):450–452. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000167407.83915.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gast GC, Frenken FJ, van Leest LA, Wendel-Vos GC, Bemelmans WJ. Intra-national variation in trends in overweight and leisure time physical activities in The Netherlands since 1980: stratification according to sex, age and urbanisation degree. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(3):515–520. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walls H, Wolfe R, Haby MM, Magliano DJ, De Courten M, Reid CM, McNeil JJ, Shaw J, Peeters A. Trends in Body Mass Index in Urban Australian Adults, 1980–2000. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(5):631–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. IIndicators of health risk factors: the AIHW view: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra 2003.

- 15.Dunstan DW, Zimmet PZ, Welborn TA, De Courten MP, Cameron AJ, Sicree RA, Dwyer T, Colagiuri S, Jolley D, Knuiman M, Atkins R, Shaw JE. The rising prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance: the Australian diabetes, obesity and lifestyle study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(5):829–834. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]