Abstract

The biosynthetic pathways to a number of natural products have been reconstituted in vitro using purified enzymes. Many of these molecules have also been synthesized by organic chemists. Here we compare the strategies used by nature and by chemists to reveal the underlying logic and success of each total synthetic approach for some exemplary molecules with diverse biosynthetic origins.

Keywords: Biocatalysis, Biosynthesis, In vitro reconstitution, Natural products, Total synthesis

1 Introduction

Synthetic chemists have long undertaken the challenge of generating natural products de novo [1]. From a synthetic point of view, natural products are of particular interest because of their complex molecular frameworks, which are often equipped with numerous stereocenters and highly reactive functional groups. Their structures raise interesting problems of regio- and stereoselectivity to be solved during their chemical preparation. The field of total synthesis has thus been a driving force in the development of novel synthetic reactions and strategies to solve these issues [1]. Synthetic routes to natural products are often characterized by their convergent approaches: numerous intermediate scaffolds can be en route to a single product. Examples of convergent approaches are syntheses of staurosporinone (1), which are discussed in this review, where over ten different synthetic routes converge to a single product [2–14].

Biosynthetic mechanisms to one molecule rarely show such a diversity of approaches; rather, multiple products can often be traced back to a core set of precursors. The complexity in biosynthetic routes derives instead from the ability of nature to develop divergent pathways from this core set of simple building blocks to give distinct molecules. These building blocks include amino acids, sugars, lipids, nucleotides, and other compounds, such as acetate, propionate, and malonate, shunted from primary metabolism, which are converted to an astonishing diversity of structures [15]. Clear examples are seen, for instance, in monoterpene biosynthesis, where a single precursor molecule is converted to a huge variety of known monoterpenes in different organisms, including (−)-(4S)-limonene, 3-carene, α-thujene, (−)-endo-fenchol, (−)-β-pinene, and 1,8-cineole [16].

Recently, some research groups have embarked on the total biosynthesis of secondary metabolites [17]. Like traditional total synthesis, where the goal is to construct a desired target molecule from easily available precursors, total biosynthesis endeavors to take simple, biologically relevant starting materials and convert them into a natural product. The difference from a chemical synthetic approach is that all reactions are carried out with purified enzymes, generally those derived from a single, microbially-derived biosynthetic operon. Beyond demonstration of a biologically based synthesis, such work is often carried out as part of studies attempting to elucidate biosynthetic logic and enzyme mechanisms, to produce new derivatives by testing enzyme substrate specificities, or to circumvent a challenging, possibly low-yielding, organic synthesis.

This review will compare the strategies taken by synthetic chemists to produce natural products with the strategies utilized by nature. What types of molecular scaffolds are made in each case in the process of assembling a natural product? Rarely will the paths be identical, but are there features that reveal a more universal logic in the construction of these molecules? Or, by contrast, are there fundamental distinctions between organic synthesis and biosynthesis? To answer these questions we have chosen – from a biosynthetic point of view – a diverse selection of secondary metabolites, ranging from relatively simple terpenes and shikimate-derived compounds to structurally more complex polyketide synthase (PKS) and nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) products. While these molecules indeed represent a diversity of chemical structures and biological roles, they also have much in common: they are relatively small, they are derived from discrete biosynthetic gene clusters, and they are accessible and of interest to synthetic chemists. Our comparison between biosynthetic/chemo-enzymatic and classical synthetic strategies in the preparation of these natural products will allow us to discuss the utility and current limitations of an intersection between total synthesis and “total” biosynthesis.

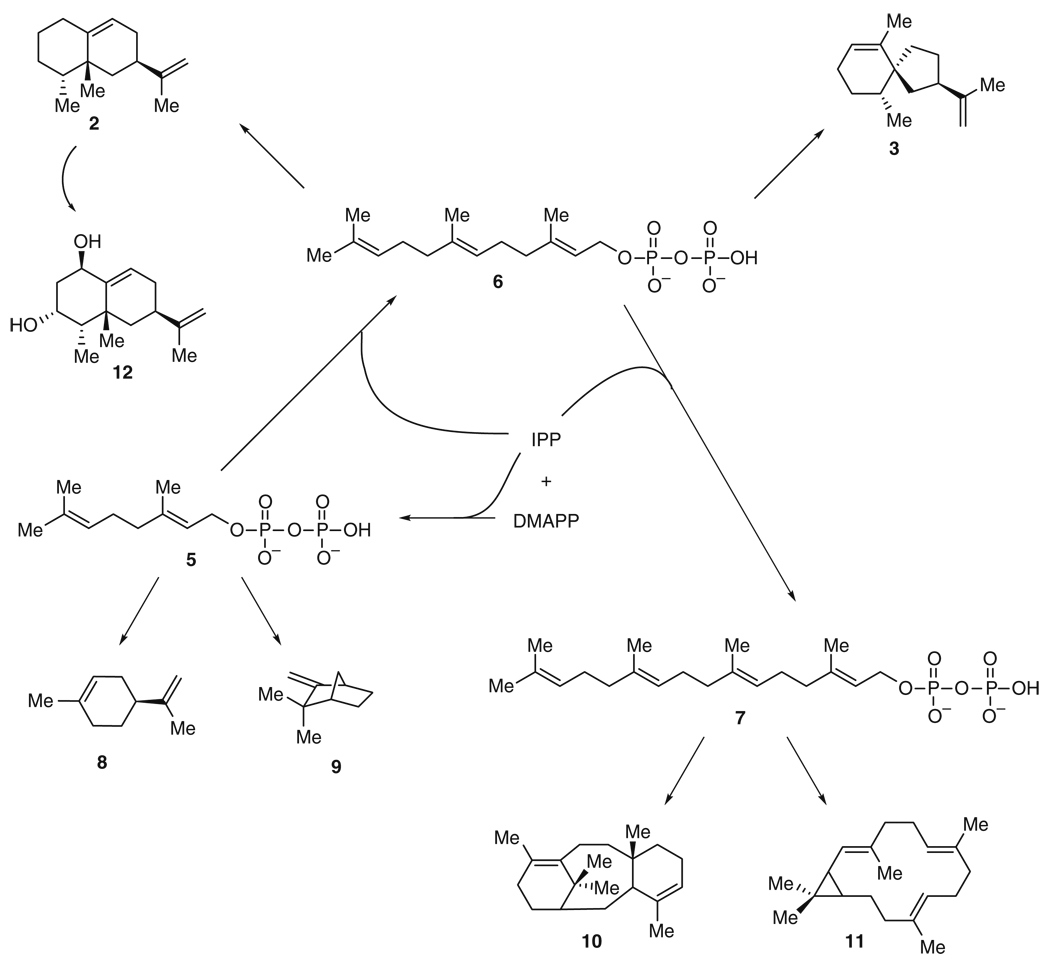

2 Sesquiterpenes: (+)-5-Epi-Aristolochene and (−)-Premnaspirodiene

Both (+)-5-epi-aristolochene (2) and (−)-premnaspirodiene (3) (Fig. 1) are representative of key intermediates in the biosynthesis of terpenes. Nature has used a divergent strategy to make a complex array of terpenes, which serve diverse roles in chemical biology, acting as volatiles, flavors, defense molecules, steroids, and vitamins, and include pharmaceutically relevant compounds such as the antimalarial drug artemisinin (4) (see Fig. 38) and the anticancer drug taxol [18]. All terpenes are derived from the condensation of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) to give a core set of precursors including geranyl diphosphate (5), farnesyl diphosphate (6), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (7) (Fig. 2). These molecules are converted, respectively, to monoterpenes (C10) such as (−)-limonene (8) and (−)-camphene (9), sesquiterpenes (C15) like 2 and 3, and diterpenes (C20), e.g., taxadiene (10) and casbene (11), through transformations that include electrophilic attacks, hydride, methyl, and methylene shifts, water quenching of carbocations, and proton abstractions [16]. These resulting intermediates are then further modified by enzymes such as cytochrome P450s, which catalyze reactions including stereospecific hydroxylations. For instance, capsidiol (12), an antifungal phytoalexin, derives from 2 [19] as a result of such additional modifications [20].

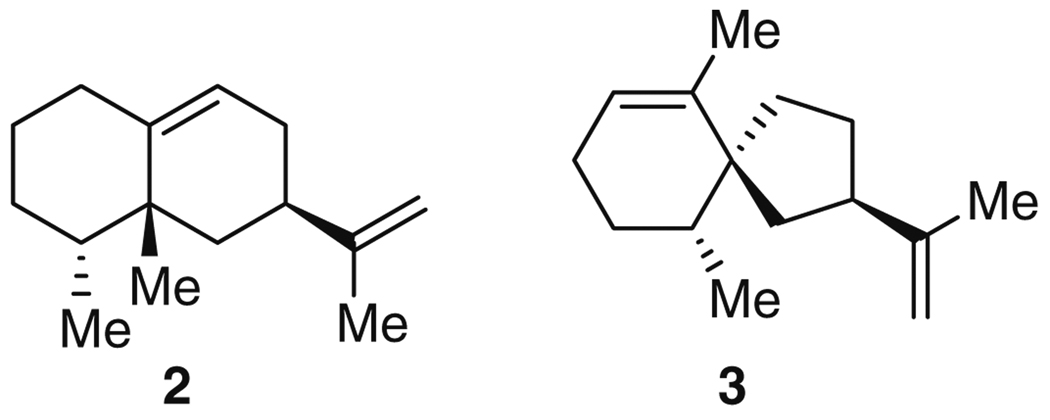

Fig. 1.

Molecular structures of (+)-5-epi-aristolochene (2) and (−)-premnaspirodiene (3)

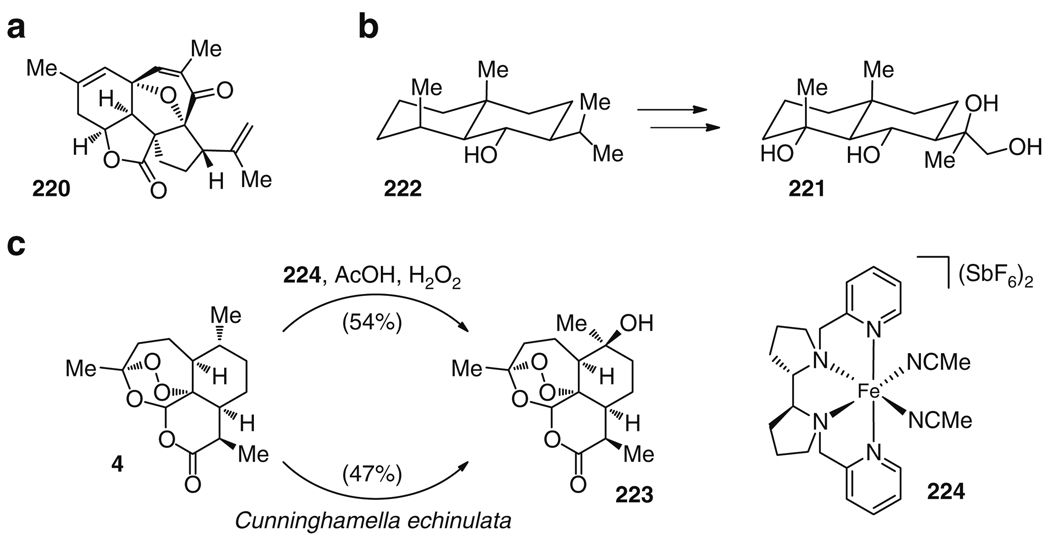

Fig. 38.

Examples of molecules prepared following new concepts in total synthesis: (a) intricarene (220) generated by protective group-free synthesis and (b) late-stage site-selective C–H oxidations to generate eudesmane-type terpenes like 222 or (c) to prepare the hydroxylated artemisinin derivative 223

Fig. 2.

Biosynthetic route to terpenes. Geranyl diphosphate (5); farnesyl diphosphate (6); geranylgeranyl diphosphate (7); (−)-limonene (8); (−)-camphene (9); taxadiene (10); casbene (11); capsidiol (12). IPP = isopentenyl diphosphate, DMAPP = dimethylallyl diphosphate

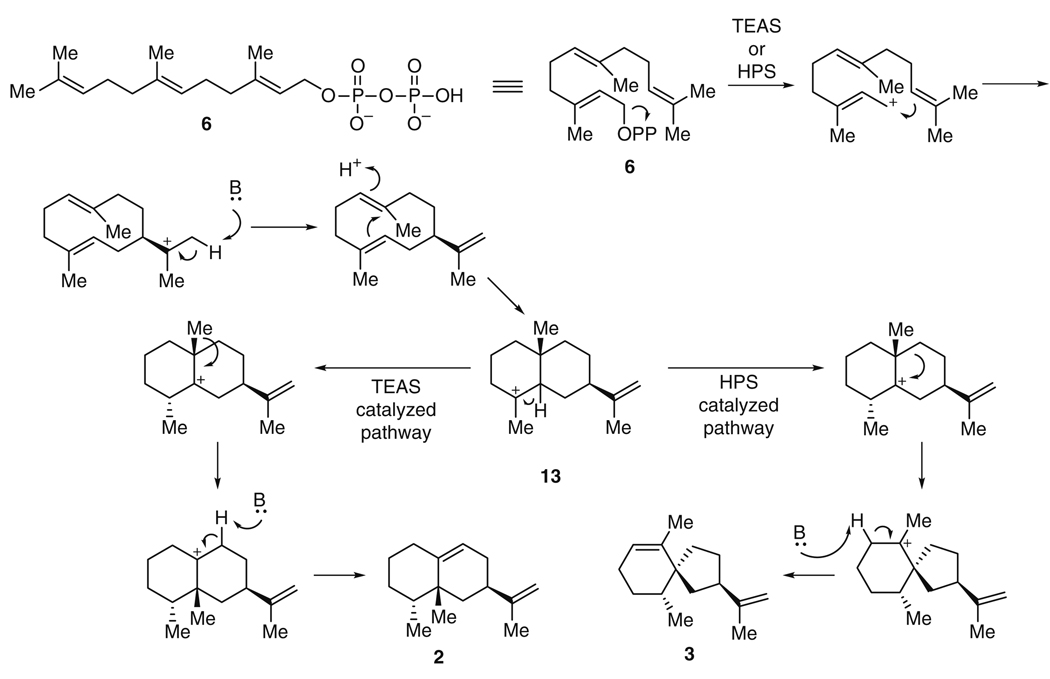

The formation of the sesquiterpene (+)-5-epi-aristolochene (2) represents, from a biosynthetic point of view, the transformation requiring the fewest steps among those discussed in this review. A single enzyme, tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (TEAS), converts the biosynthetic precursor, farnesyl diphosphate (6), to 2 with a kcat/KM of 0.3 µM−1 min−1 [21, 22]. Nonetheless, this single transformation itself is complex: TEAS catalyzes two ring closures, a hydride and a methyl migration, and a proton abstraction to form a double bond (Fig. 3). Interest in TEAS was dramatically increased when it was discovered that a highly related enzyme, henbane premnaspirodiene synthase (HPS), isolated from Hyoscyamus muticus, with 75% identity at the amino acid level to TEAS, was able to catalyze a completely different outcome with the same precursor [23]. Both HPS and TEAS are thought to have similar reaction mechanisms, through intermediate 13, where they diverge. While TEAS initiates a 1,2-methyl shift in 13 to give finally 2, HPS instead triggers a 1,2-shift of the cycloalkyl substituent to form 3. Overall, HPS catalyzes two ring closures, a methylene shift, and abstraction of a distinct proton to give (−)-premnaspirodiene (3), a spirovetivane with three stereocenters (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Proposed mechanisms for the formation of (+)-5-epi-aristolochene (2) and (−)-premnaspirodiene (3) from farnesyl-diphosphate (6) by the action of TEAS and HPS, respectively

How TEAS and HPS can give rise to such distinct terpene intermediates has been probed by crystallographic, biochemical, and site-directed mutagenesis approaches. The crystal structure of TEAS revealed the enzyme as a two-domain alpha-helical protein with a hydrophobic active site containing two Mg2+ ions for the coordination of the farnesyl diphosphate substrate 6. A complex of the protein with analogs of 6 enabled identification of amino acid side chains likely to modulate key reaction steps [24]. The authors proposed a mechanism for (+)-5-epi-aristolochene (2) formation [24] consistent with earlier studies [23]. This crystallographic study was the groundwork for comparative analysis with HPS. Although the structure of HPS itself has not been determined, molecular modeling of HPS, followed by docking with energy-minimized putative substrates and contact mapping, identified nine amino acids, among those that were distinct between the two enzymes, likely to be responsible for determining the catalytic outcome. The activity of HPS could be installed in TEAS by replacement of these nine amino acids from HPS into the TEAS protein. Conversely, the activity of TEAS could be introduced by substitution of the nine TEAS residues into the HPS background [25]. A systematic evaluation of 418 of the 512 possible mutant combinations in the TEAS protein background led to a consideration of the catalytic landscape of the terpene cyclase activity, and a realization that single amino acid mutations did not necessarily cause predictable changes in enzyme activity [26].

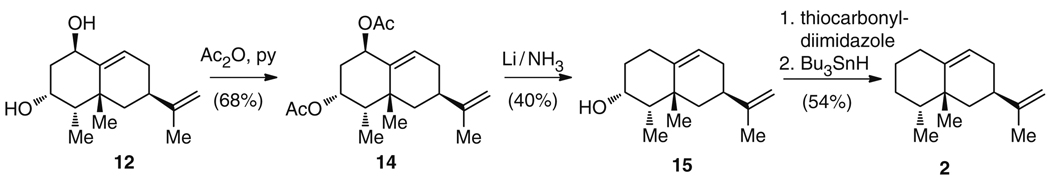

Unlike the biosynthetic route to 2 and 3, the synthetic approaches to these molecules are characterized, instead, by deconstruction of terpene natural products further along the biosynthetic pathway. Preparation of (+)-5-epi-aristolochene (2) has so far only been carried out using a semisynthetic strategy from the natural product 12 [27], which is available from pepper (Capsicum annum) fruits in high quantities [28]. The synthetic route started with O-acetylation of 12 to give 1,3-di-O-acetylcapsidiol 14, followed by reduction to furnish 1-deoxycapsidiol (15) in 27% yield (Fig. 4). Alcohol 15 was derivatized to deliver a thiocarbonylimidazole adduct, which was finally converted to 2 in 54% combined yield. The synthesis is notable in that it occurs in a reverse order to that seen naturally; capsidiol (12) is thought to be biosynthetically derived from (+)-5-epi-aristolochene (2) [19, 29], and, semisynthetically, 2 is derived from 12 [27].

Fig. 4.

Synthesis of (+)-5-epi-aristolochene (2) from the natural product capsidiol (12)

The semisynthesis of 3 utilized a ring contracting rearrangement reaction similar to the respective biosynthetic transformation (Fig. 5). The starting material santonin (16) [30], itself a natural product [31], was converted in a three step sequence into ester 17, which in turn was equipped with a TMS group and reduced to give alcohol 18 in 37% overall yield. Epoxidation of the remaining double bond using oxone furnished 19, the precursor of the rearrangement reaction, in 91% yield. In the following key synthetic step, the epoxide ring was opened using the Lewis acid BF3, leading to the semistable carbocation 20, which, after a 1,2-shift of the cycloalkyl residue to give 21, and elimination of the TMS group, furnished 64% of the spirovetivane 22. The preparation of 3 was concluded by mesylation of the primary alcohol, elimination of the mesylate leaving group to give 23, and final removal of the secondary alcohol in 27% overall yield. (−)-Premnaspirodiene (3) has also been synthesized as an intermediate en route to (−)-solavetivone from dihydrocarvone [32].

Fig. 5.

Synthetic route to (−)-premnaspirodiene (3)

Although there are a limited number of syntheses to (+)-5-epi-aristolochene (2) and (−)-premnaspirodiene (3), it is clear that the biosynthetic approach, involving a single enzyme whose specific amino acid side chains determine the catalytic outcome, is more simple than the synthetic routes. Nonetheless, the synthesis to 3 is an elegant demonstration of the capacity of organic synthesis to generate the spirovetivane structure in a biosynthetically inspired manner. While this chemical route nicely utilized a biomimetic rearrangement reaction, it is far more complex with 12 steps separating santonin (16) from 3 (Fig. 5).

3 Salicylate Containing Siderophores: Yersiniabactin and Pyochelin

Iron is an essential requirement for life; however, in aerobic environments the majority of it is present in its insoluble ferric (Fe3+) form. In order to sequester this metal from iron-limited habitats, some microorganisms synthesize siderophores, which are small molecules that have a high affinity for iron and other transition metals [33–35]. Siderophore production in Yersinia species was first proposed by Wake and coworkers, who observed that an iron-limited Yersinia pestis culture was able to promote the growth of another cocultured strain [36]. However, the side-rophore yersiniabactin (24) was not isolated until almost two decades later by Haag and colleagues, who detected a catechol functional group and reported the molecular mass of the iron chelator to be 482 Da [37]. Subsequently, the structure of 24 was elucidated and was shown to be comprised of two thiazoline rings, a thiazolidine ring, a malonyl unit, and a phenol moiety derived from salicylate [38]. Crystallization studies of 24 with Fe3+ revealed that it forms a hexadentate ligand with iron via the phenolate, the alcoholate on the malonate-derived moiety, the terminal carboxylate, and the three cyclized cysteine nitrogens (see Fig. 7a) [39].

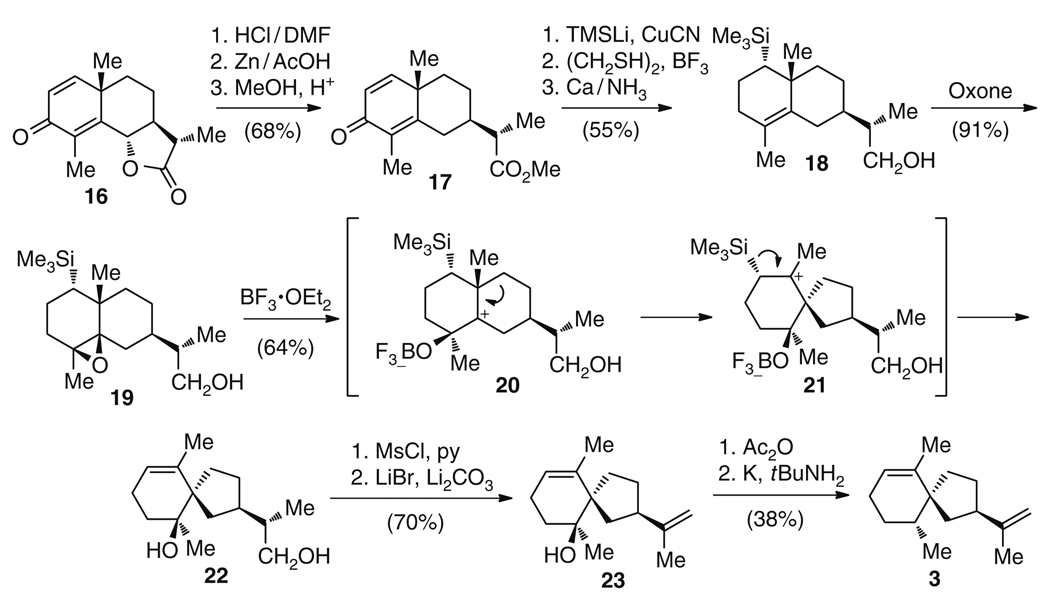

Fig. 7.

Biosynthesis of (a) 24 and (b) 25 from intermediate 33. One molecule of 24 can bind ferric iron while two molecules of 25 are required for Fe3+ chelation

Various bacteria, predominantly pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae, have been shown to biosynthesize 24, including Y. pestis, the causative agent for pneumonic and bubonic plague [40], the enteric pathogens Yersinia pseudotuberculosis [41] and Yersinia enterocolitica [42], as well as uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli [43, 44] and the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae [45]. Yersiniabactin (24) is secreted by cells in low-iron environments. The siderophore’s high affinity for Fe3+, with a stability constant of 4 × 1036 M−1 [46], allows it to sequester iron from lower affinity host heme-binding proteins, such as the transferrin glycoproteins which have stability constants of approximately 1020 M−1 [39]. As a result, 24 is a virulence factor essential for the pathogenicity of producing species [47–49]. Siderophore biosynthesis is, therefore, becoming an increasingly appealing therapeutic target in the development of novel antibiotics against infectious diseases, such as biosynthesis substrate mimics which inhibit compound production [50, 51].

Biosynthesis of 24 occurs via a nonribosomal peptide synthetase/polyketide synthase (NRPS/PKS) mechanism. The enzymatic machinery is encoded by the ybt gene cluster [52–54] which is located on a virulence conferring high-pathogenicity island (HPI), and which also includes the genes for regulation [55, 56], transport [57], and uptake [49, 58] of the siderophore and the ferric-siderophore complex. Although the HPI does not encode the necessary genes to be self-transmissible [59], it is still highly mobilizable, possibly via phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer [60] or by integration on a transmissible plasmid [61].

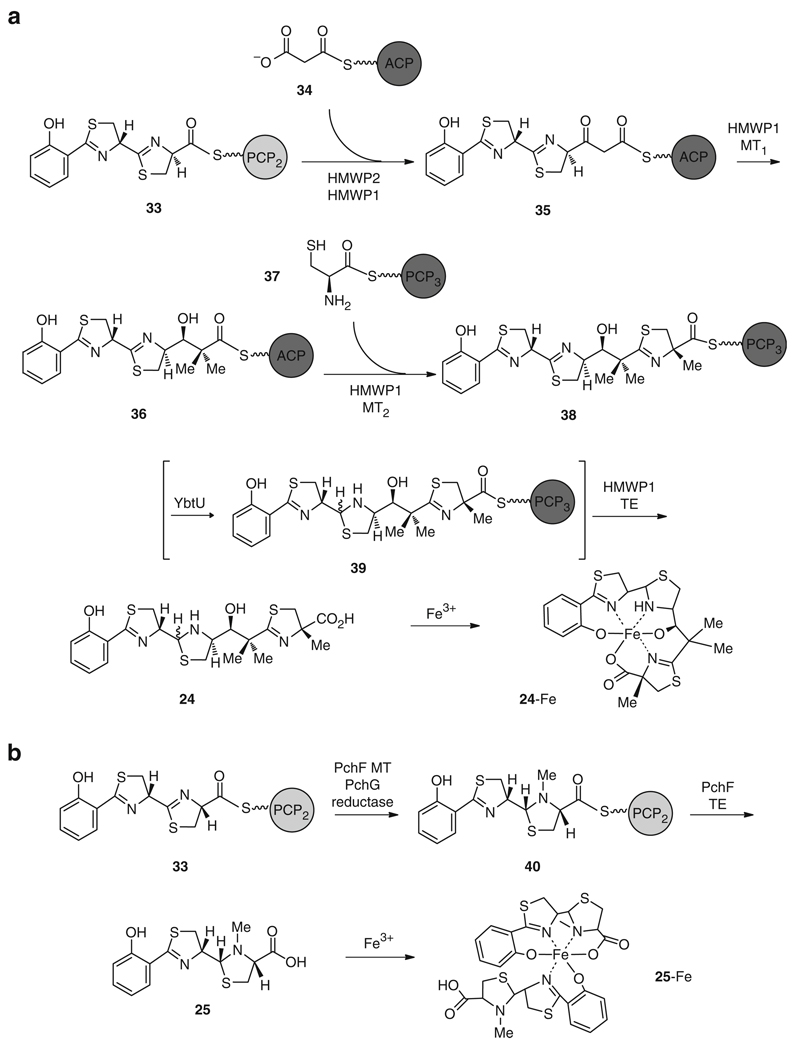

Assembly of 24 (Figs. 6 and 7a) proceeds in a linear, modular fashion across the NRPS/PKS interface [62]. First, the salicylate synthase YbtS converts chorismic acid (26) to salicylic acid (27) [63, 64], which is then activated as an adenylate by the salicyl-AMP ligase, YbtE. Salicyl-AMP is tethered as a thioester to the aryl carrier protein (ArCP) of the NRPS module, HMWP2, to give 28. HMWP2 catalyzes the activation of l-cysteine (29) as a PCP-bound acyl adenylate 30, which is subsequently epimerized [65], condensed with 28, and cyclized to a thiazoline ring to yield 31. A second l-cysteine molecule (29) is then activated as 32 and incorporated to the nascent peptide to yield the bisthiazoline intermediate 33. Transfer of intermediates across the NRPS and PKS interface is facilitated by aryl-, peptidyl-, and acyl- carrier proteins (ArCP, PCP1, PCP2, ACP, and PCP3) that are first activated into their holo forms by the addition of a phosphopantetheinyl arm, derived from coenzyme A (CoA), which is catalyzed by the phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) YbtD [66]. Following the incorporation of the two thiazoline rings, the substrate 33 is transferred from the terminal PCP2 of HMWP2 to the PKS/NRPS hybrid enzyme, HMWP1, for elongation with an ACP-bound malonate unit 34 to yield 35, which is subsequently double Cα-methylated and reduced to furnish 36. The methyl groups are derived from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and are attached by a methyltransferase domain within the HMWP1 PKS machinery. HMWP1 also catalyzes the activation of the third l-cysteine (29) which is bound to PCP3 as thioester 37 and is then incorporated, cyclized, and methylated to give 38. Conclusion of the pathway occurs by transfer of the substrate, from the final PCP3 domain to the terminal thioesterase (TE), for release of the mature yersiniabactin (24). The second thiazoline ring is reduced to thiazolidine 39 by the reductase, YbtU [62], presumably before release by the TE domain, although the timing of this reaction within 24 biosynthesis remains unknown. In addition to the four yersiniabactin (24) synthetase enzymes necessary for in vitro biosynthesis (YbtE, YbtU, HMWP1, and HMWP2), in vivo production also requires the type II thioesterase YbtT which is proposed to remove misprimed structures from the NRPS/PKS enzyme complex [67].

Fig. 6.

Four enzymes (one salicylate-AMP ligase YbtE/PchD, two NRPS and/or NRPS/PKS enzymes HMWP1/PchE and HMWP2/PchF, and one reductase YbtU/PchG) are required for the in vitro biosynthesis of (a) yersiniabactin (24) and (b) pyochelin (25). (c) The initial stages of 24 and 25 biosynthesis proceed via a similar mechanism from chorismic acid 26 to the salicylatebisthiazole intermediate 33

Siderophores produced via NRPS or NRPS/PKS mechanisms comprise the majority of currently reported one-pot in vitro reconstitutions, likely due to their elegantly simple and modular biosynthetic machinery, and also largely due to the efforts of the Walsh laboratory. Total biosynthesis of yersiniabactin (24) was carried out by this group with four substrates (salicylic acid (27), l-cysteine (29), SAM, and malonyl-CoA), three cofactors (NADPH, coenzyme A, and ATP) and five enzymes (YbtE, YbtU, HMWP2, HMWP1, and Sfp) [62]. The NRPS/PKS enzymes were phosphopantetheinylated in a single reaction by the PPTase Sfp from Bacillus subtilis. The 22 catalytic reactions resulting in the total biosynthesis of 24 proceeded with a relatively inefficient final turnover rate of 1.4 min−1, which is attributable to the poor transfer of the substrate from HMWP2 (33) to the PKS/NRPS hybrid enzyme HMWP1 (35) [62], as well as to the large number of enzyme reactions required for in vitro reconstitution.

Total in vitro biosynthesis of a structurally similar siderophore, pyochelin (25), was also previously carried out by the same laboratory [68]. Pyochelin (25), which is produced by the human lung pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia [69–71], possesses a phenol moiety followed by a thiazoline and thiazolidine ring [72], as in 24. However, 25 does not contain the dimethyl malonate or the final thiazoline ring and, instead, possesses an N-methylation on the thiazolidine ring that is not present in 24. Two molecules of 25 are required to bind Fe3+ [73, 74]. One molecule of 25 binds Fe3+ as a tetradentate ligand with the phenolate hydroxyl, the two nitrogens, and the terminal carboxylate. The other molecule can bind as a bidentate with either the hydroxyl and thiazoline nitrogen or the thiazolidine nitrogen and the carboxylate (Fig. 7b). Analogous to 24 reconstitution, the enzymes required for in vitro reconstitution of 25 included a salicyl AMP-ligase (PchD), two NRPS enzymes (PchE and PchF) for the incorporation and cyclization of two l-cysteines (29) to give 31 and 33 [65], and a reductase domain for conversion of the thiazoline ring to a thiazolidine ring (PchG) (Figs. 6 and 7b) [68, 75]. Subsequent SAM-mediated N-methylation of the thiazolidine ring, delivering 40, and final release of 25 from the NRPS machinery is carried out by the methyltransferase and thioesterase encoded within the NRPS enzyme PchF (Fig. 7b). The overall rate of turnover in 25 in vitro biosynthesis was approximately 2 min−1, which is consistent with the final efficiency of 24 reconstitution [62, 68]. However, the oxidized pyochelin-like intermediate in 24 biosynthesis (hydroxyphenyl-thiazolinyl-thiazolinyl-CO2H) was reportedly formed with the higher catalytic efficiency of 6 min−1, which indicates that the double module HMWP2 is more efficient at incorporating and cyclizing two cysteines than the two-enzyme counterpart (PchE and PchF) in the biosynthesis of 25. Further, it seems that the incorporation of a dimethyl malonate and a third cyclized cysteine into 24 does not significantly reduce the in vitro catalytic efficiency when compared to that of 25.

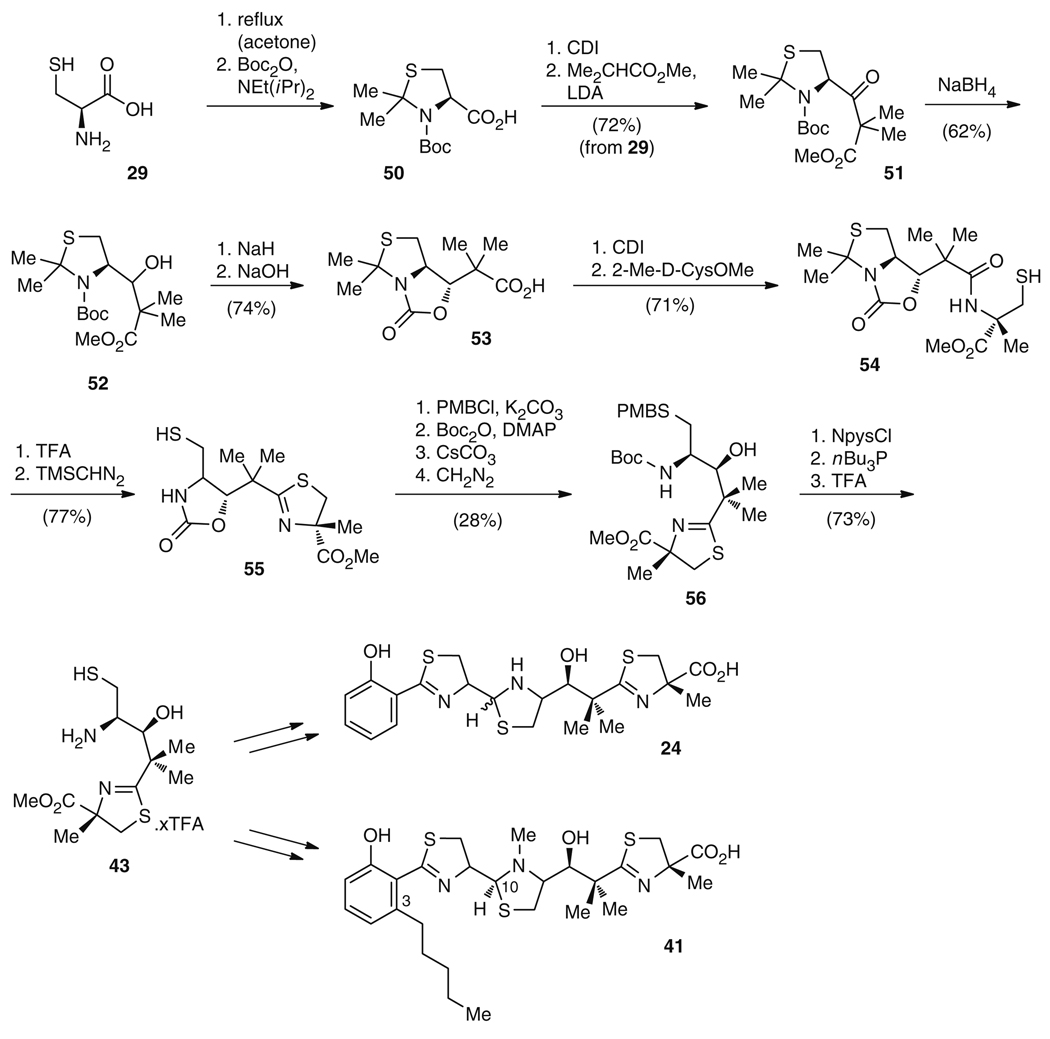

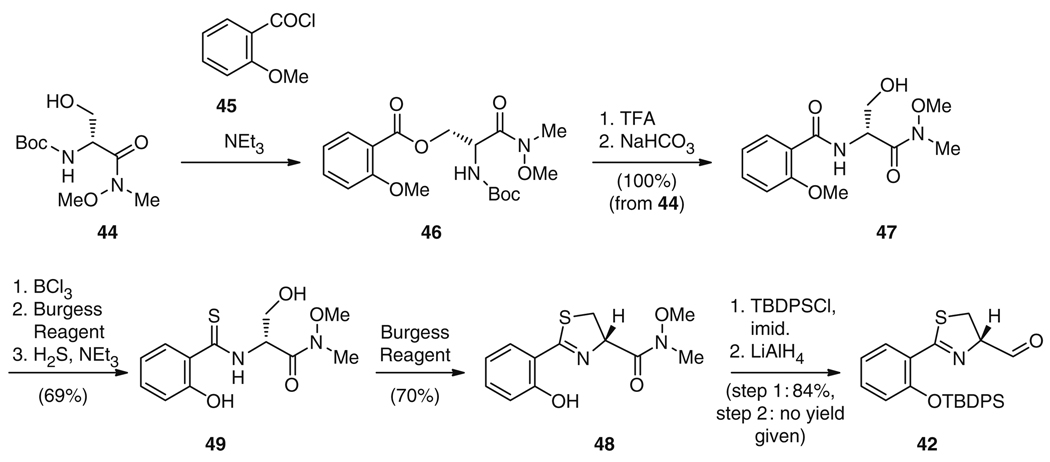

Only one strategy has been reported for the total chemical synthesis of 24 [76], which may be indicative of the complexity of this synthesis, as well as the relatively high fermentation yields (over 100 mg L−1) and ease of purification of 24 from Yersinia spp. culture [37, 38]. Ino and Murabayashi [76] adapted their synthesis strategy from their previous total synthesis of the antimycoplasma antibiotic micacocidin (41) (see Fig. 9) [77]. Structurally, 41 is identical to 24 except for the absolute configuration at position C10, an additional pentyl chain at C3 of the phenol group, and an N-methylation on the thiazolidine ring. Total synthesis of 24 proceeded via condensation of two molecular building blocks, the aldehyde 42 (Fig. 8) and intermediate 43 from 41 synthesis (Fig. 9). The aldehyde 42 was synthesized by condensation of the Weinreb amide 44 with methoxy benzoyl chloride 45 to yield ester 46 (Fig. 8). Subsequent N-deprotection and treatment with NaHCO3 resulted in intramolecular attack of the free amine at the ester to give the rearranged amide 47 in 100% yield from 44. Following O-demethylation of the phenolic methoxy residue, 48 was constructed by converting the amide first into a thioamide 49 and finally into a thiazoline in 48% yield using Burgess reagent. After protection of the phenol group, reduction of the Weinreb amide 48 yielded aldehyde 42 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9.

The thiazoline intermediate (43) from micacocidin (41) and yersiniabactin (24) synthesis derived from l-cysteine (29) [76, 77]

Fig. 8.

Chemical route to aldehyde 42, an intermediate in 24, 25, and 58 synthesis

The remainder of 24 was synthesized as for micacocidin (41) [77] (Fig. 9). The synthesis started with conversion of l-cysteine (29) to the thiazolidine carboxylate 50 using the strategy of Kemp and Carey [78]. Notably, l-cysteine (29) is also utilized in the biosynthesis of 24 and 25 despite epimerization to the d-form during thiazoline ring formation [65], which highlights a similarity between the synthetic and biosynthetic logic. Following elongation to a β-keto-carboxylic acid 51 and reduction of the keto group to give alcohol 52, 53 was formed by deprotonation of the secondary alcohol using NaH, leading to intramolecular carbamate formation, and subsequent hydrolysis of the methyl ester in 33% overall yield [77]. Condensation with 2-methyl-d-cysteine methyl ester delivered intermediate 54, which was transformed into 55 by cyclization of the thiazoline ring and removal of the acetonide (55% overall yield). Protection of the thiol and amino groups and cleavage of the oxazolidine ring afforded alcohol 56 in four steps and 28% yield. The synthesis was concluded by consecutive removal of the PMB and Boc protecting groups [76] to furnish 73% of 43 for subsequent condensation with 42 (Fig. 9). These units were linked by nucleophilic attack of the thiol and the amino group in 43 to the aldehyde function in 42 under basic conditions. Subsequent O-deprotection delivered ester 57 in 43% yield, which was saponified to yield the final compound, 24 (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Synthesis of 24 via condensation of aldehyde 42 with the micacocidin (41) synthesis intermediate 43

Interestingly, Ino and Murabayashi also synthesized the “truncated” yersiniabactin derivatives pyochelin I (25) and neopyochelin II (58) as a mixture during their analysis of the stereochemical preferences at the C9 and C10 chiral centers of 24. For 25 synthesis (Fig. 11a), instead of condensation with the micacocidin intermediate 43, aldehyde 42 was reacted with N-methyl-l-cysteine (59) and deprotected to yield a diastereomeric mixture of 25 and 60, which was treated with zinc chloride to afford 25 and 58 in a 5:1 mixture in 46% overall yield [76]. This shared synthetic route, although not entirely biomimetic, does highlight the analogous pathway of 24 and 25 biosynthesis. A simpler three-step synthesis of 25 by Cox and colleagues did follow a completely biomimetic strategy, apart from the N-methylation of cysteine prior to cyclization of the thiazolidine ring. Synthesis occurred via condensation of salicylnitrile 61 with l-cysteine (29) to afford carboxylic acid 62, followed by t-hexylborane reduction to give aldehyde 63 (Fig. 11b) [79]. Condensation of the aldehyde in 63 with N-methyl-l-cysteine (59) yielded the final compound 25 in 2% overall yield. Several groups have since optimized the synthetic access to aldehyde 63 in order to increase the overall yield to 25 [80–82].

Fig. 11.

Synthesis of 25 via (a) intermediate 42, also utilized in 24 and 58 synthesis and (b) a biomimetic strategy from salicylnitrile 61 and l-cysteine 29

The number of reactions required for total biosynthesis and chemical synthesis of yersiniabactin (24) is comparable, with 22 [62] and 30 [76, 77] reactions, respectively. However, two very different strategies are used by nature and by chemists in the production of this compound. The enzymatic pathway biosynthesizes the siderophore in a linear manner, while the chemical route convergently synthesizes two molecular halves and condenses them to the final product. The number of steps required for thiazolidine formation in the chemical synthesis of 24 by Ino and Murabayashi demonstrates the complexity of this approach over the elegant simplicity of the biosynthetic mechanism.

4 Dihydroxybenzoate Containing Siderophores: Enterobactin and Derivatives, Myxochelin A and Vibriobactin

The siderophore enterobactin (enterochelin) (64) is a cyclic lactone of three N-(2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)-l-serine moieties produced by E. coli under iron stress. Enterobactin (64) was first isolated from iron-limited cultures of Salmonella typhimurium [83], E. coli [84], and Aerobacter aerogenes [84]. Structural analysis has confirmed that 64 chelates iron as a hexadentate ligand via the two hydroxyl groups on each catechol moiety (see Fig. 13) [85]. Of all the siderophores characterized to date, 64 has been shown to have the highest affinity for ferric iron, with a stability constant of 1052 M−1 [86, 87], which is remarkable, considering the affinity of EDTA for iron is 27 orders of magnitude lower. In mammals, serum albumin [88] and siderocalin [89, 90] bind the hydrophobic 64 which impedes siderophore-mediated transfer of iron to bacteria. Consequently, bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella enterica have evolved various linear and cyclic C-glucosylated analogs of 64, known as salmochelins 67–70 (see Fig. 14) [91, 92], which are resistant to binding by these mammalian proteins [93–95]. A derivative of salmochelin, microcin E492 (71), has been isolated from Klebsiella pneumonia [96], and has been shown to be a pore-forming antibiotic that possesses an N-terminal, 84 amino acid peptide, which is attached to a linear C-glucosylated 64 derivative (72) [97–100]. The structural similarities of microcin E492 (71) with enterobactin (64) and salmochelins 67–70 may allow the uptake of this antibiotic into the inner membrane of other bacteria that possess siderophore-specific receptors, which could then effectively kill these bacterial competitors [93].

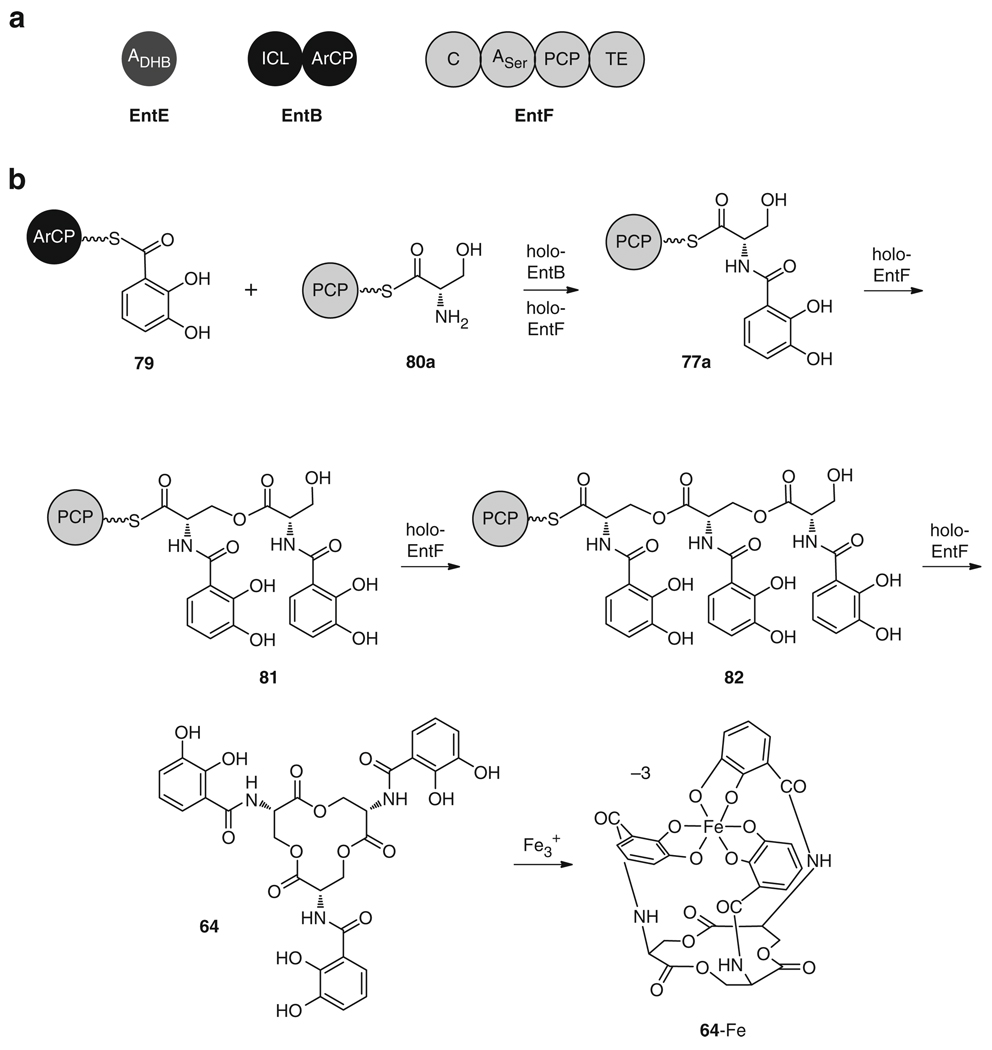

Fig. 13.

(a) Three enzymes (EntE, EntB and EntF) are required for the in vitro reconstitution of 64. (b) Biosynthesis of 64 by the stepwise condensation of three ArCP-bound DHB groups (79) and three PCP-bound l-serines (80a). Enterobactin (64) chelates ferric iron with high affinity via the six phenolate hydroxyl groups

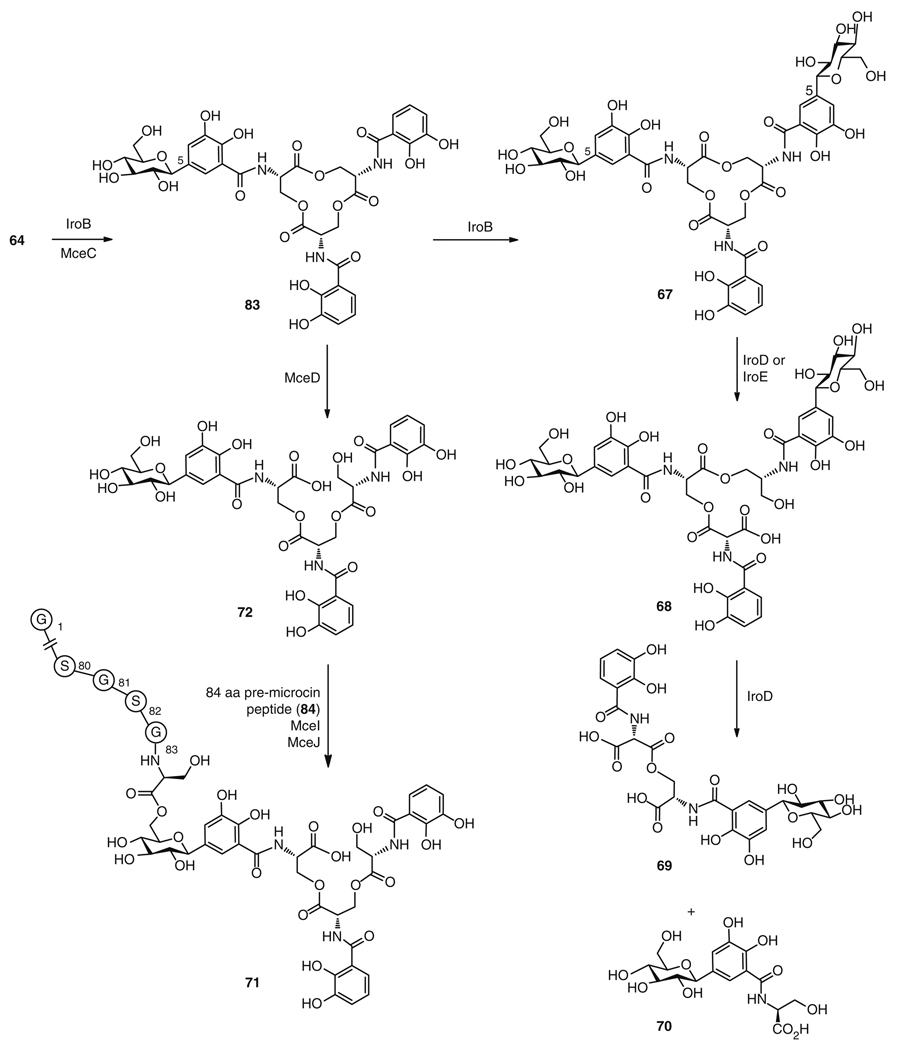

Fig. 14.

Biosynthesis of microcin E492 (71), salmochelin S4 (67), and salmochelin SX (70) from the enterobacin (64) precursor

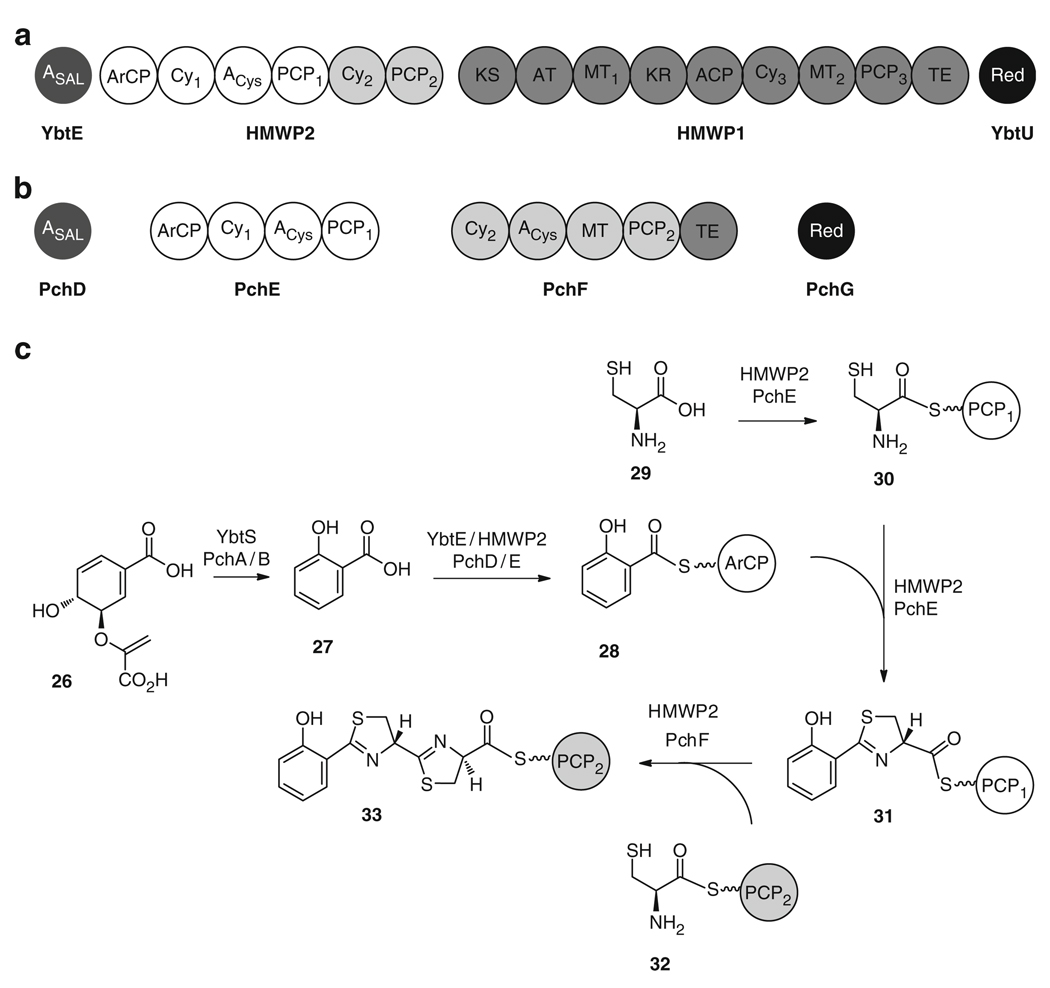

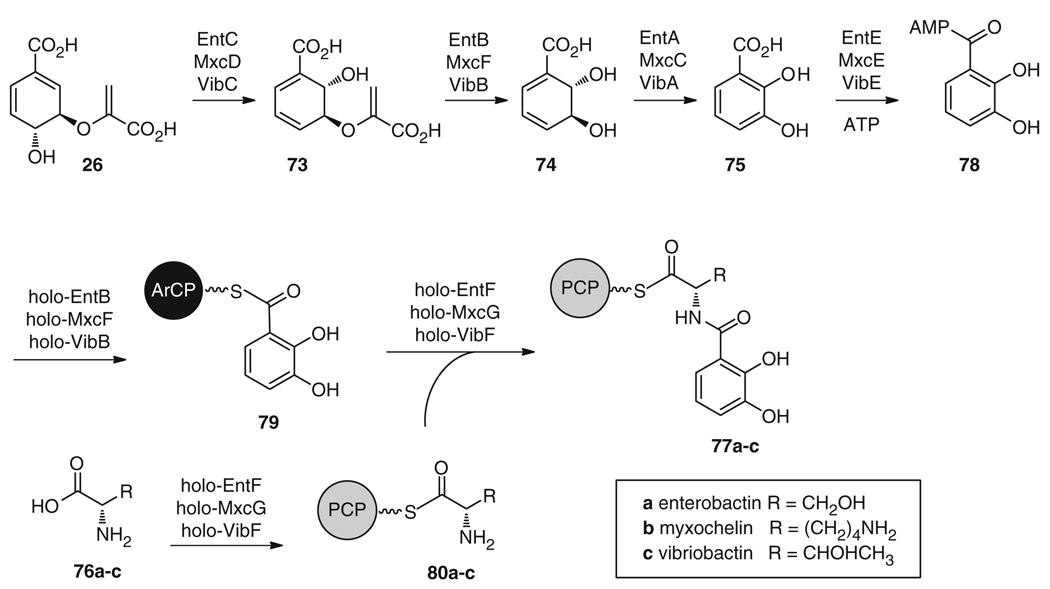

The initial stages of enterobactin (64) biosynthesis are common to many other 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) containing siderophores (Fig. 12), including myxochelin (65) and vibriobactin (66). First, chorismic acid (26) is converted to isochorismic acid (73) by the isochorismate synthase EntC [101–103], then to 2,3-dihydro-2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (74) by the N-terminus of the isochorismate lyase (ISL) EntB [104, 105], and finally to the substrate 75 by the dehydrogenase EntA [106]. Further assembly occurs via an NRPS mechanism (Fig. 12) with the stepwise condensation of DHB (75) and an amino acid 76a–c to form a DHB-amino acid monomer bound as a thioester to the PCP domain (77a–c). Specifically for enterobactin (64) biosynthesis (Figs. 12 and 13), three N-(2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl) serine units are synthesized in three iterative rounds by the NRPS enzymes, followed by cyclization of the three monomers into the final tricyclic lactone. The adenylation domain of EntE activates 75 as an acyl-adenylate 78, which is then loaded onto the C-terminus aryl carrier protein domain (ArCP) of EntB to give 79 [104], while the adenylation domain of EntF activates l-serine (76a) as l-serine-AMP. The condensation domain of EntF then catalyzes amide bond formation between each DHB-ArCP unit 79 and an l-serine-PCP molecule 80a to form 77a [107]. Subsequently, the terminal thioesterase of EntF catalyzes the stepwise ester bond formation between each of the three tethered N-(2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl)- l-serine moieties (77a, 81, 82) as they are biosynthesized, as well as the cyclization and release of the final 12-membered trilactone 64 [108] (Fig. 13).

Fig. 12.

The initial stages of 64, 65, and 66 biosynthesis proceed via the same mechanism, with the condensation of DHB (75) (from chorismic acid 26) with a PCP-tethered amino acid 80 (serine (a), lysine (b), or threonine (c), respectively)

Following this biosynthetic route to the core structure of 64, diverse tailoring steps can lead to glycosylated derivatives. In salmochelin S4 (67) biosynthesis (Fig. 14), 64 is glucosylated at the C5 position of two of the catechol groups by the C-glycosyltransferase, IroB [109] to give first 83 and then 67. A variety of salmochelin analogs then arise from linearization of 67 into the DHB-serine trimer salmochelin S2 (68) by the esterases IroD or IroE; or cleavage into the respective monoglucosylated dimer salmochelin S1 (69) or glucosylated monomer salmochelin SX (70) via IroD, during iron release [110, 111]. For the biosynthesis of microcin E492 (71), the IroB homolog, MceC, and the trilactone hydrolase, MceD, function to glucosylate and cleave the precursor 64 to a linear monoglucosyl derivative 72 [99, 100]. The enzymes MceI and MceJ then form a heterodimer to attach the glucose group of the linear trimer to the C-terminal serine of an 84-amino acid long, ribosomally synthesized, peptide chain (84), which is cleaved from a precursor peptide encoded by the gene mceA, to give 71 (Fig. 14) [17, 99, 112].

In the in vitro reconstitution of 64 biosynthesis, the enzymes EntB and EntF were first activated to their holo forms via the cognate EntD PPTase before final purification [107]. Total biosynthesis then proceeded via a one-pot reaction with the three enzymes (EntE, holo-EntB, and holo-EntF), two substrates (DHB (75) and l-serine (76a)), and ATP as a cofactor [107]. The final catalytic efficiency of 64 total reconstitution was extremely high at 121 min−1, which reflects the elegant simplicity of the biosynthetic strategy as well as the relatively small number of enzymes, substrates, and cofactors required for in vitro biosynthesis [107]. Incubation of 64 with the C-glycosyltransferase, IroB, in vitro resulted in sequential C5 glucosylation of the catechol groups, to form mono- (83), di- (67), and triglucosyl enterobactin derivatives [109]. In this way, salmochelin S4 (67) was reconstituted by IroB in vitro from the precursor 64 using the substrate UDP-glucose and the reducing agent TCEP. Although the majority of the microcin E492 (71) biosynthetic enzymes have been individually characterized, there are currently no reports on the total reconstitution of 71, most probably because this would require the integration of both ribosomal and nonribosomal peptide syntheses in vitro.

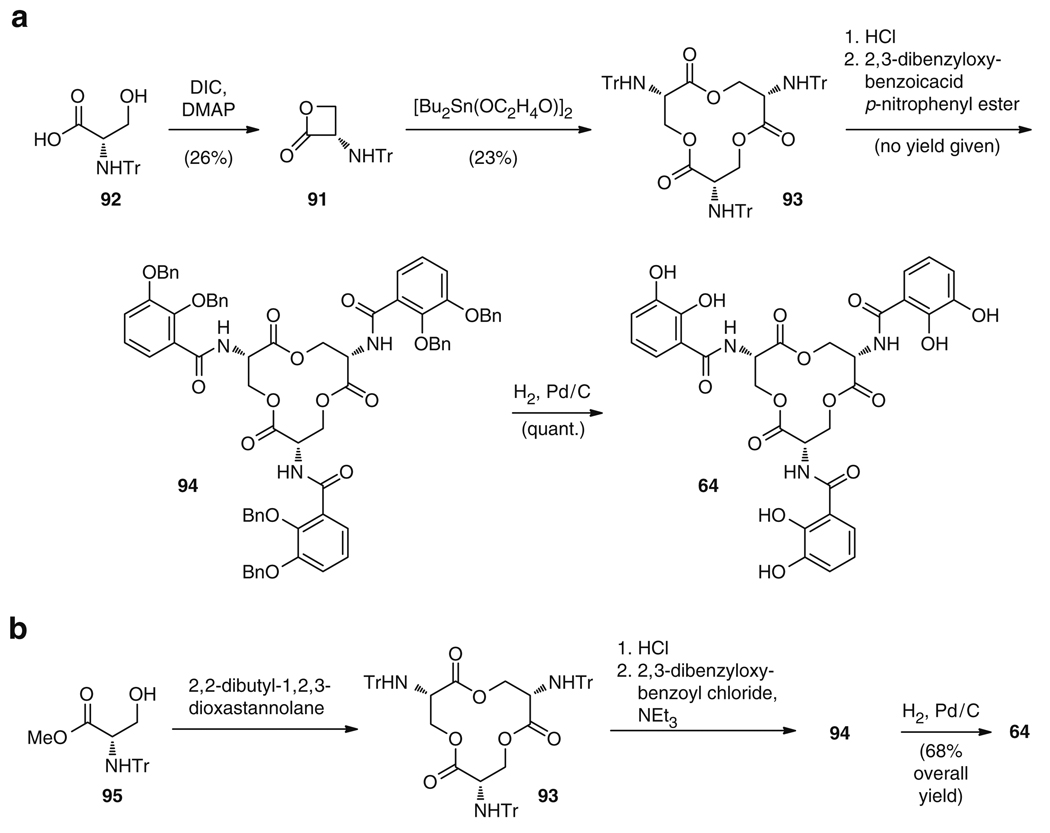

There have been seven total syntheses of 64, compared to the single synthesis of yersiniabactin (24). The greater focus on 64 synthesis may be due to its more potent activity, simpler synthetic strategy, and the comparably low yields that can be isolated from culture (0.6 mg L−1 from S. typhimurium [83], 15 mg L−1 from E. coli [84], and 22 mg L−1 from A. aerogenes [84]). Each of the syntheses of 64 follows one of two different strategies. The first two synthetic routes utilize the condensation of three serine derivatives followed by cyclization of the trilactone and subsequent addition of the DHB groups (75) [113, 114], which is in the opposite order to the biosynthetic mechanism. The synthesis described by Corey and Bhattacharyya (Fig. 15) [113] started with the generation of the p-bromophenacyl ester 85 from N-benzyloxycarbonyl-l-serine (86) in 98% yield. THP-protection of the alcohol function and removal of the acid protective group with Zn paved the way for generation of an activated thioester of 85, which was in situ condensed with one equivalent of 85 to give 87 in 69% overall yield. Renewed deprotection of the acid and coupling of an in situ generated thioester with another equivalent of 85 delivered the cysteine trimer 88, which upon deprotection of the alcohol and the acid function furnished compound 89 in 51% overall yield. Macrocyclization using the same thioester activation strategy as above gave the cyclic tripeptide 90 (40% yield), which was further transformed into the natural product 64 by hydrogenolytic cleavage of the Cbz groups and subsequent attachment of the 2,3-dihydroxybenzoyl moieties no yield given. The later synthesis by Rastetter [114] followed the same strategy but used different protection and deprotection methods. Both syntheses, however, resulted in low overall yields of approximately 1%. In a similar manner, Rogers utilized N,N′-dibenzyl-l-serine as the precursor for cyclization to the protected trilactone, which increased the yield of this step by five times over the previous two strategies [115].

Fig. 15.

The first chemical synthesis of 64, which involves the condensation of three serine derivatives (86) with subsequent cyclization and addition of DHB groups

The second synthesis approach, carried out by Shanzer and Libman, employed l-serine β-lactones 91, derived from N-trityl l-serine (92) in 26% yield (Fig. 16a). Stannoxane mediated cyclotrimerization directly gave 93 in 23% yield. Subsequent HCl-induced replacement of the trityl groups, and addition of the nitrophenyl esters of 2,3-bis(benzyloxy)benzoic acid to the free amines thus obtained, delivered 94 (no yield given), which was transformed quantitatively into the natural product 64 by final hydrogenolytic cleavage of the benzyl protective groups [116]. Although this route effectively reduced the number of steps required for the synthesis of 64, the overall yield was only increased to approximately 6% [116]. In order to enhance the total yield of this organotin strategy, the low efficiency steps, namely the conversion of 92 to 91 and then to the tricyclic lactone, were targeted for optimization. These processes were replaced by converting an N-Boc-l-serine precursor to the corresponding β-lactone and subsequently to the trilactone [117]. This increased the overall yield to approximately tenfold of the original Shanzer and Libman strategy. A variation on the organotin template based strategy was used in order to bypass the relatively low efficiency β-lactonization of the N-tritylserine substrate (92), which increased the overall yield to approximately 50% [118]. Using l-serine methyl ester as a starting material, an N-trityl-l-serine methyl ester (95) was generated and used to produce the tritylated trilactone 93. In an optimized strategy (Fig. 16b), 95 was reacted with 2,2-dibutyl-1,2,3-dioxastannolane as the template to afford 93, which was then converted to the hexabenzylenterobactin derivative 94 by deprotection and treatment with 2,3-dibenzyloxybenzoyl chloride [119]. Following this, the benzyl protective groups were cleaved by Pd-C catalyzed hydrogenolysis, which yielded 64 in a highly efficient overall yield of 64%. The synthetic approaches to 64 have, thus far, not utilized the elegant, biomimetic route involving the condensation of DHB (75) to l-serine (76a) and subsequent cyclization of three monomers to form 64. In fact, attempts at stepwise condensation of DHB-serine monomers have not been successful, due to undesired racemization of the monomers [120]. These unsuccessful attempts highlight an advantage of natural biosynthesis where the substrate specificity of enzymes can effectively dictate the biosynthetic route and simultaneously protect sensitive parts of the molecule, which suggests a fundamentally efficient logic to nature’s biosynthetic rationale.

Fig. 16.

Chemical syntheses of 64 via (a) the first and (b) the currently most efficient organotin template strategies

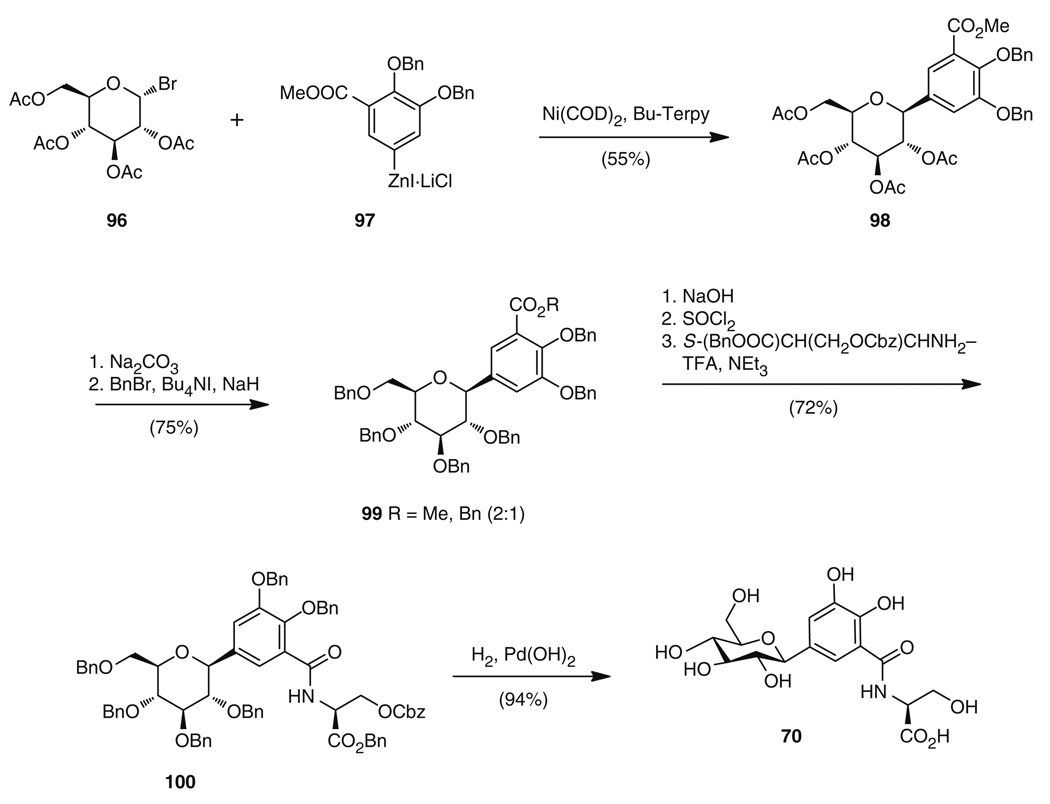

Recently, a total synthesis of salmochelin SX (70) has been reported which used cross-coupling of acetobromo-α-d-glucose 96 with arylzinc derivative 97 to furnish 98, followed by full deacylation and perbenzylation to give 99. Subsequent saponification of the methyl/benzyl ester, formation of the acid chloride, and addition of a protected l-serine unit yielded 100. Final deprotection formed the glucosyl-DHB-serine 70 in 28% overall yield (Fig. 17) [121]. This strategy involved the stepwise addition of the aryl moiety and serine (76a) to the sugar portion, which is in the opposite order to the biosynthetic rationale.

Fig. 17.

Total synthesis of salmochelin SX (70)

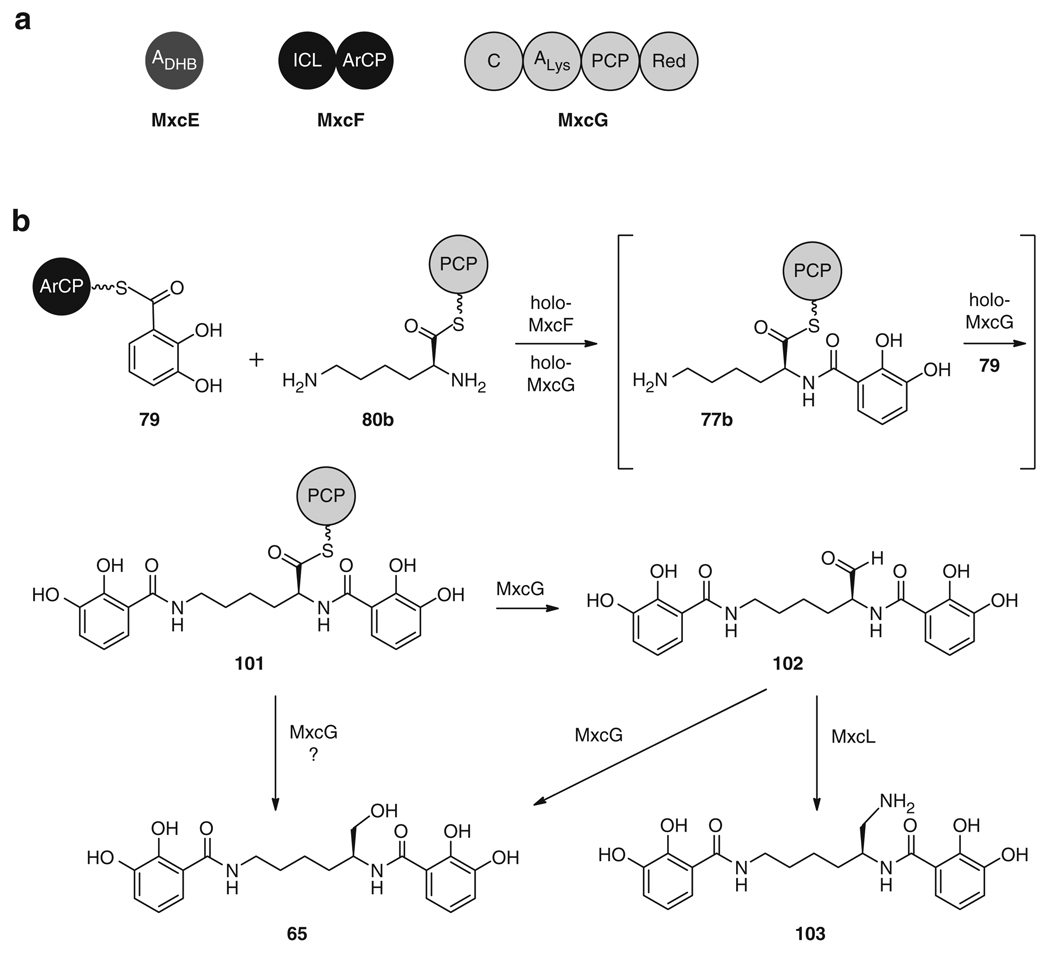

Another DHB-containing siderophore that has been reconstituted in vitro is myxochelin A (65). This siderophore, which is produced by Stigmatella aurantiaca [122] and Nonomuraea pusilla [123], is comprised of two DHB residues (75) attached to the amino groups of lysine (76b), and has also been shown to possess antitumor activity [123]. The initial stages of 65 biosynthesis parallel those of 64, with production of DHB (75) via the EntC, EntB, and EntA homologs, MxcD, MxcF, and MxcC (Fig. 12) [122]. In the same way, 75 is activated as DHB-AMP (78) by the EntE homolog MxcE and transferred to the ArCP domain of MxcF to form 79. The NRPS module MxcG then activates lysine (76b) as an acyl adenylate bound to the PCP as 80b and catalyzes the formation of amide bonds between this residue and two molecules of ArCP-bound DHB (79) (Fig. 18). This dual bisacylation activity, which could possibly occur sequentially via intermediate 77b or simultaneously to give 101 directly, has previously only been reported in vibriobactin (66) biosynthesis [124]. Further, the unique mechanism of release of the final compound 65 from the NRPS via the action of a terminal reductase domain, which converts PCP-bound thioester 101 into aldehyde 102 or, possibly, directly into myxochelin A (65) [122], is found in only a handful of known biosynthetic systems. Reductive transamination, catalyzed by MxcL, can also further convert 102 to the amine myxochelin B 103.

Fig. 18.

(a) Total in vitro biosynthesis of 65 requires three enzymes, MxcE, MxcF, and MxcG. (b) Biosynthesis of 65 and 103 from two ArCP-bound DHB units (79) and one PCP-bound lysine (80b)

Total biosynthesis of 65 was performed using the enzymes MxcE, holo-MxcF, and holo-MxcG with the substrates DHB (75) and lysine (76b), and the cofactors ATP and NADPH [125]. The apo-ArCP and -PCP domains of MxcF and MxcG were first activated by coexpression with the PPTase MtaA from myxothiazol biosynthesis [126]. Myxochelin A (65) was synthesized at a linear rate for the endurance of the assay (65 h), with over 800 nmol mL−1 of compound formed during that time [125].

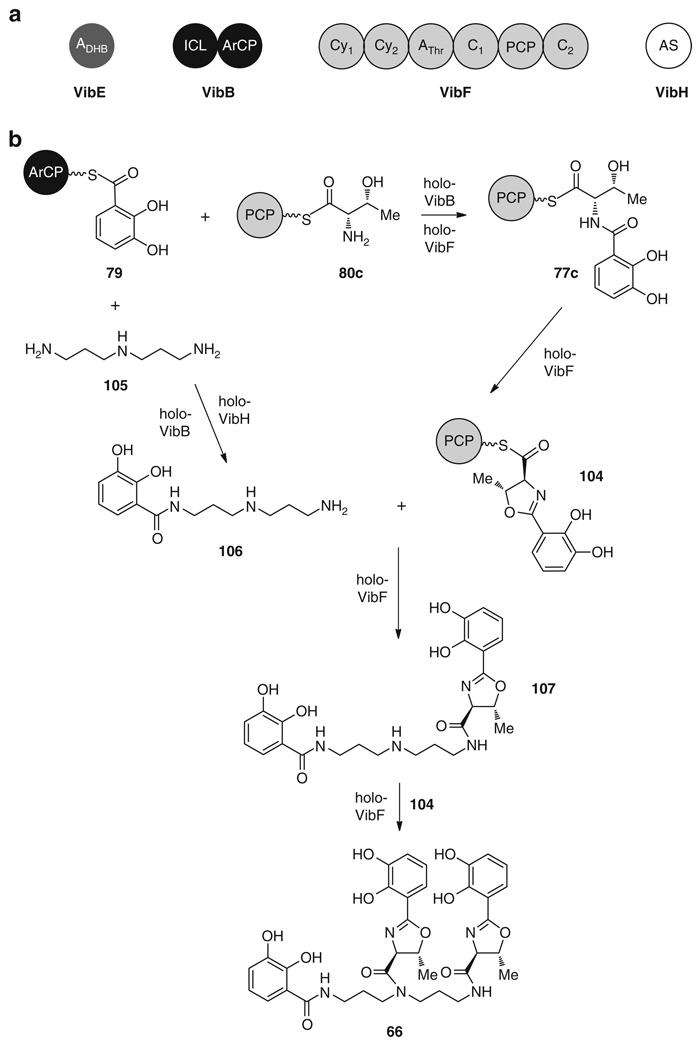

The cholera-causing pathogen Vibrio cholerae is able to produce the siderophore vibriobactin (66) [127] via an NRPS mechanism [128, 129] similar to that in 64 and 65 biosynthesis. Once again, DHB (75) is biosynthesized using the pathway specific enzymes VibC, VibB, and VibA (EntC/MxcD, EntB/MxcF, and EntA/MxcC homologs) (Fig. 12). After acylation of DHB (75) by VibE (EntE/MxcE homolog), the acyl adenylate (78) is loaded onto the ArCP of VibB (EntB/MxcF homolog) to give 79 for condensation with the VibF-activated and -tethered aminoacyl-threonine 80c. Following this, an amide bond is formed between these two building blocks yielding 77c, and the threonine portion is cyclized to the corresponding oxazoline 104 by VibF (Fig. 19) [124]. A final DHB unit (75) is also loaded onto VibB as 79 for condensation with the primary amine of norspermidine 105 via the amide synthase VibH, resulting in unbound, soluble DHB-norspermidine 106 [128]. Two DHB-oxazoline monomers, still tethered as thioesters on VibF as 104, are then sequentially transferred to the primary and secondary amines of the DHB-norspermidine molecule to yield 107 and 66, respectively [124].

Fig. 19.

(a) Total in vitro biosynthesis of 66 requires three enzymes, VibE, VibF, and VibH. (b) Biosynthesis of 66 from three ArCP-bound DHB units (79), two PCP-bound threonines (80c), and one norspermidine (105)

Reconstitution of the biosynthesis of 66 was carried out in a similar manner to the 64 and 65 total biosyntheses, using the enzymes VibB, VibH, VibE, VibF and Sfp, the substrates DHB (75), l-threonine (76c) and norspermidine (105), and the cofactors ATP and CoA [124]. Vibriobactin (66) was formed in vitro at a linear rate of 15 µM min−1 over 20 min with large scale total biosynthesis yielding 1.6 mg [124]. Interestingly, during the directed evolution of the VibB ArCP, the Walsh laboratory replaced EntB with mutant VibB enzymes in the in vitro biosynthesis of 64 in order to assay increased activity [130]. VibB and corresponding high activity mutants were able to complement EntB activity, albeit at a lower efficiency than the natural enzyme. However, this example demonstrates the effective strategy of nature to utilize one pathway in the production of several divergent compounds.

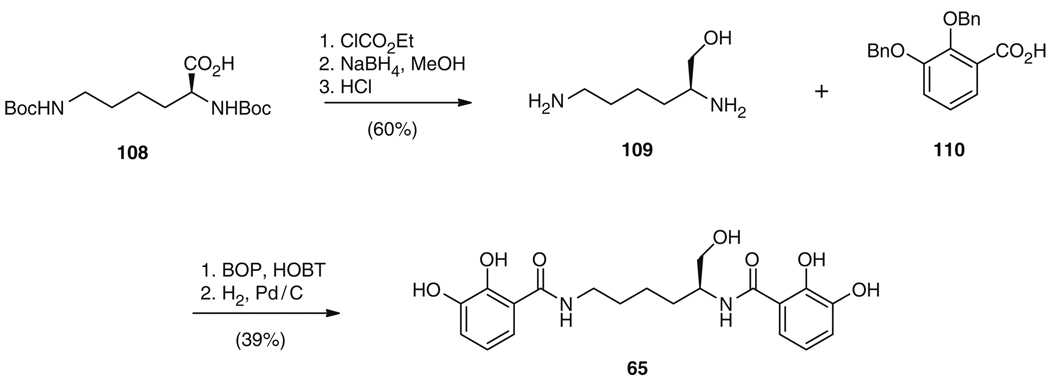

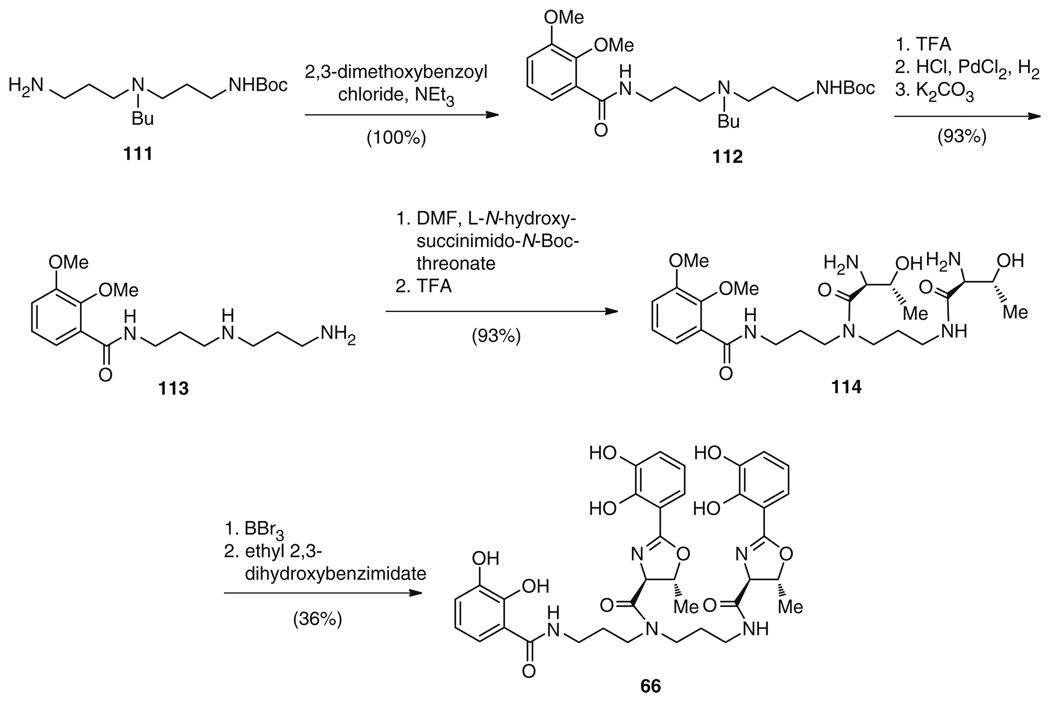

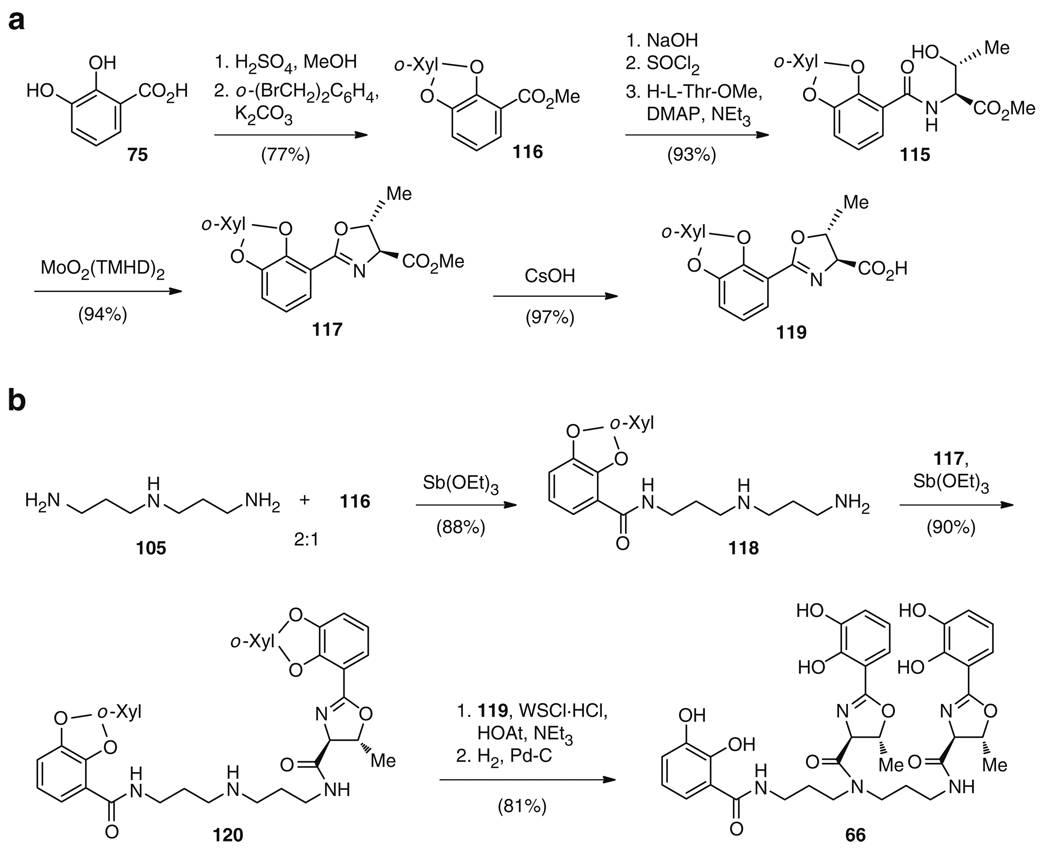

The total biosynthetic route to both 65 and 66 involves the condensation of one or two DHBs (75) with either lysine (76b), threonine (76c), or norspermidine (105), with further cyclization of the threonine residues to DHB-oxazolines and – in the case of 66 – condensation of the latter to the central backbone. Similarly, the synthetic strategy to 65 reflects this biosynthetic approach, with the reduction of a t-Boc-protected lysine 108 to the corresponding alcohol, removal of the protecting groups to give 109, and subsequent installation of benzylated 2,3-DHB 110 (Fig. 20) [123]. Following this, the benzyl groups were removed to afford the final compound 65 in 23% overall yield. In contrast, 66 was first synthesized using an entirely different strategy. Although Bergeron and colleagues [131] began biomimetically, with the condensation of a norspermidine derivative 111 and 2,3-dimethoxybenzoyl chloride to yield a trisubstituted norspermidine 112 (Fig. 21), the synthesis diverges from the biosynthetic strategy from this point onwards. Compound 112 was N-deprotected to the monoacylated norspermidine 113, which was then bisacylated with a thioester activated N-Boc-l-threonine derivative with subsequent removal of the Boc groups to give 114 (Fig. 21) [131]. After O-demethylation, the cyclization of the two l-threonine amides to oxazolines was carried out in ethyl 2,3-dihydroxybenzimidate, which also accomplished the addition of the two DHB moieties to give 66 in 31% overall yield. This strategy is in direct contrast to the biosynthetic route where dehydration and cyclization of the threonines is catalyzed after the condensation with DHB (75), but prior to the attachment of these residues to the norspermidine core. Using a more biomimetic rationale, Sakakura et al. reasoned that a higher yield to 66 could be achieved by an early construction of the DHB-oxazoline group (Fig. 22a) [132]. Thus, N-(o,m-dialkoxybenzoyl)-l-threonine (115), derived from DHB (75) in a five-step sequence via 116 in 72% yield, was cyclized to 2-(o,m-dialkoxyphenyl)oxazoline (117) in 94% yield using molybdenum catalysis. This catalyst effectively mimicked the activity of the cyclization domains (Cy) from 66 biosynthesis. The DHB-norspermidine derived molecule 118 was in turn synthesized from condensation of norspermidine (105) and 116 (Fig. 22b). Subsequently, the methyl ester 117 and the corresponding acid 119 were sequentially condensed to the primary and the secondary amines of 118 and 120, respectively, exactly as occurs in biosynthesis. Finally, the o-xylylene groups were removed by hydrogenolysis to yield 66 with an overall yield of 64% from 105 [132].

Fig. 20.

Total synthesis of 65 from t-Boc protected lysine (108)

Fig. 21.

Total synthesis of 66 via the original chemical synthesis route

Fig. 22.

Total synthesis of 66 via a biomimetic strategy

A comparison of siderophores that have been both totally biosynthesized and chemically synthesized reveals that the more structurally simple compounds (pyochelin, myxochelin) can be synthesized following a biomimetic route, whereas more complex molecules (yersiniabactin, enterobactin, vibriobactin) often tend to be synthesized via unique strategies. This trend highlights the specialized roles of in vitro biosynthesis and chemical synthesis in the production of highly functionalized natural products. However, the biomimetic approach to the structurally more complex 66 [132] demonstrates that an effective synthetic rationale can sometimes be ascertained from the biosynthetic mechanism.

5 Indole Alkaloids: Staurosporine Aglycone, K252c

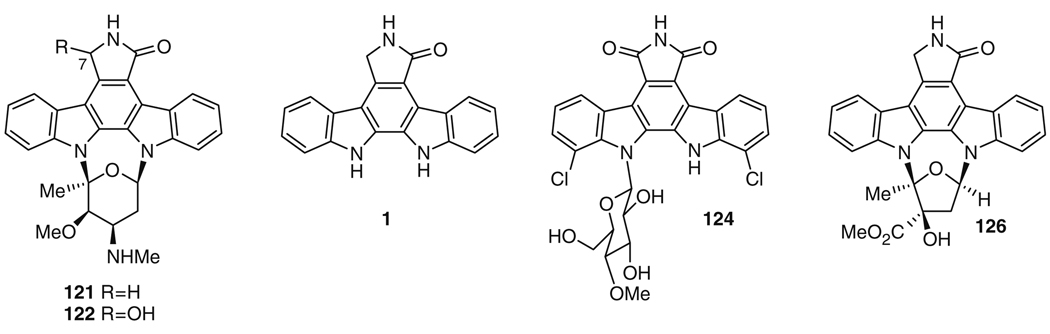

The potent protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine (121) was first isolated in 1977 from the actinomycete strain AM-2282 [133], which was later reclassified as Lentzea albida [134]. Staurosporine (121) has received immense attention as a potential chemotherapeutic, possessing nanomolar inhibitory activity against protein kinase C (PKC) [135]. Its inhibitory activity against multiple protein kinases in cells has prompted an investigation of related molecules with less potent, but more PKC-specific, activity [12, 136]. A related molecule, UCN-01 or 7-hydroxystaurosporine (122), differing from staurosporine (121) only in the presence of a hydroxyl at C7 (Fig. 23) [137], is in Phase II clinical trials against renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and lymphoma, as well as against small cell lung carcinoma, as a dual agent with topotecan [138], suggesting that molecules related to 121 are strong candidates for use as chemotherapeutics [139]. Staurosporine (121) has been pursued as a synthetic target, with the total synthesis reported by both the Danishefsky and Wood research groups [140–143].

Fig. 23.

Staurosporine (121) and related molecules

An understanding of the biosynthetic pathway to 121 has also been hotly pursued. With the elucidation of the putative biosynthetic gene cluster for staurosporine in 2002 [144], as well as those of closely related bisindoles [145–149], numerous groups have sought to determine the biosynthetic logic of staurosporine production, to understand mechanisms of intriguing biosynthetic enzymes, and to generate modified natural products using combinatorial biosynthesis [144, 150–159]. Most of the early steps in staurosporine biosynthesis are now well explored. However, the enzymes StaG and StaN, involved in the unique glycosylation chemistry – catalyzing the coupling of the staurosporine aglycone (1) at the two indole nitrogens to an l-ristosamine sugar – while well-explored in vivo [160, 161], have not yet been shown to be active in vitro, perhaps due to the poor quality of expression of enzymes from recombinant systems.

In its own right, K252c (1), the staurosporine aglycone, also known as staurosporinone, is a molecule of high interest. Like staurosporine (121), it was first isolated as a natural product, from a strain that produces a variety of related molecules [162]. It also possesses strong activity against protein kinases. Although no single, one-pot, total biosynthesis has been demonstrated for 1, each of the steps necessary for its production have been separately reported. Our discussion will, therefore, focus on K252c (1), given its synthesis both chemically and in vitro, using purified enzymes, and given its strong similarities to staurosporine (121), including structural, biosynthetic, and pharmaceutical features.

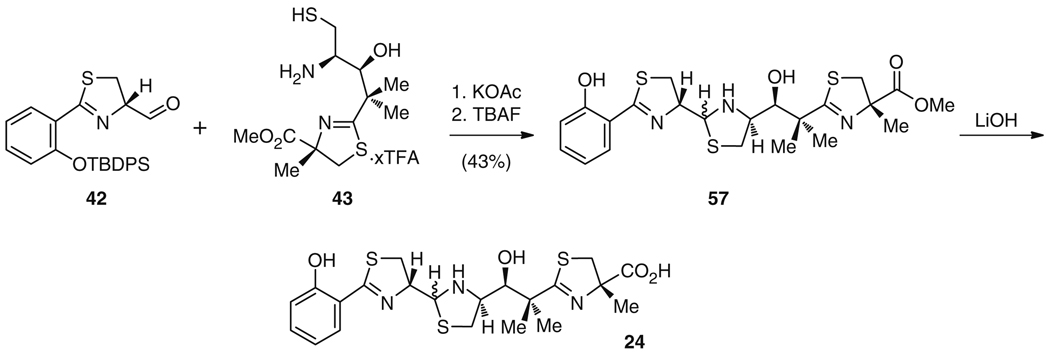

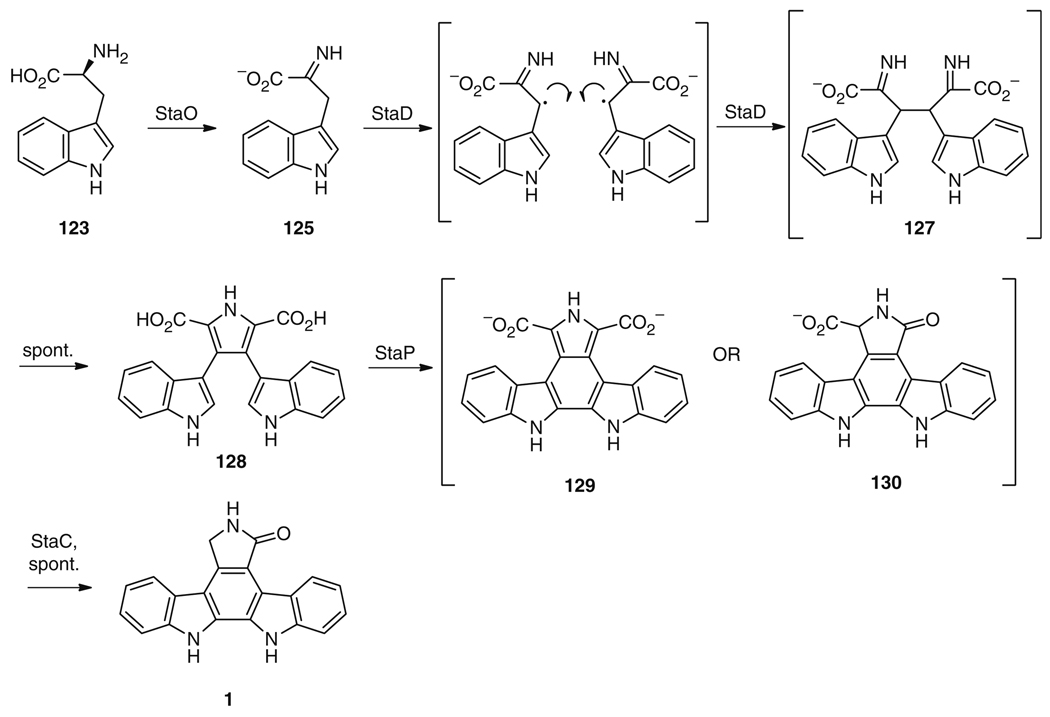

The biosynthesis of 1 follows a pattern seen for all bisindoles that have been biosynthetically investigated thus far [17, 163, 164]: two molecules of l-tryptophan (123) are oxidized and then dimerized to give an initial bisindole skeleton (Fig. 24). Historically, the biosynthesis of staurosporine (121) has been investigated in parallel with that of rebeccamycin (124), a related bisindole. Both molecules are thought to be biosynthesized through nearly identical routes to give the aglycone portions of the molecules, and the corresponding biosynthetic enzymes in each pathway are highly related. In the case of staurosporine (121), l-tryptophan (123) is first converted to indole-3-pyruvic acid imine (125) by the action of the flavindependent enzyme StaO. However, only RebO, the corresponding enzyme from the rebeccamycin (124) biosynthetic pathway, has been investigated in vitro [151, 152]. While RebO has a preference for 7-chloro-l-tryptophan (the rebeccamycin precursor) over l-tryptophan (123) (the staurosporine precursor) with a 57-fold greater kcat/Km for the chlorinated substrate [151], it is nonetheless capable of converting 123 and molecular oxygen to indole-3-pyruvic acid and hydrogen peroxide using flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as a cofactor with a kcat/Km of 7.9 min−1 mM−1 [151]. Improved conversion of 123 may be possible with the use of StaO itself, related homologs such as InkO from the K252a (126) biosynthetic pathway [145], active in a heterologous expression system [165], or alternate StaO homologs identified from genomic sequencing of other staurosporine producers [166].

Fig. 24.

Proposed biosynthetic route to 1 from l-tryptophan (123)

The next reaction in the biosynthetic pathway, the dimerization of two molecules of 125, is thought to occur through radical bond formation to give rise to 127 (Fig. 24). This unusual reaction – dimerization of two unreactive carbon centers – is catalyzed by an equally unusual enzyme, StaD, a heme-containing enzyme with ~1,100 amino acids [158], which has relatively few sequence relatives in sequence databases. Each of the currently known StaD sequence relatives are thought to play equivalent roles in related biosynthetic pathways [145–149, 155, 159], and all characterized homologs contain heme iron. Work on the related enzyme RebD (54% identity) has shown that the preferred substrate is indole-3-pyruvic acid imine (125) [152], a substrate preference that is likely to hold for StaD as well. Spontaneous chemistry is then thought to result in production of chromopyrrolic acid (128) [149, 152, 158].

The final set of biosynthetic reactions to 1 involves the four-electron oxidation of chromopyrrolic acid (128). This transformation can be carried out with 128, the cytochrome P450 enzyme StaP, flavodoxin NADP+ reductase, ferredoxin, NAD(P)H, and the putative flavin-dependent oxidoreductase StaC [153]. Crystal structures are currently available for StaP itself [157] and for RebC, the homolog of StaC from the rebeccamycin biosynthetic pathways [154]. These structural data coupled with chemical investigations [167] and modeling studies [156] suggest that StaP catalyzes the aryl-aryl coupling of 128 to give an intermediate that may be 129 or 130. StaC is then likely to stabilize one of the intermediates in its active site – both suggested intermediates would decompose in solution [167], and the homolog RebC in crystalline form “traps” a tautomer of 130 in its active site [154] – and to react with the intermediate to generate the staurosporine aglycone (1) (Fig. 24).

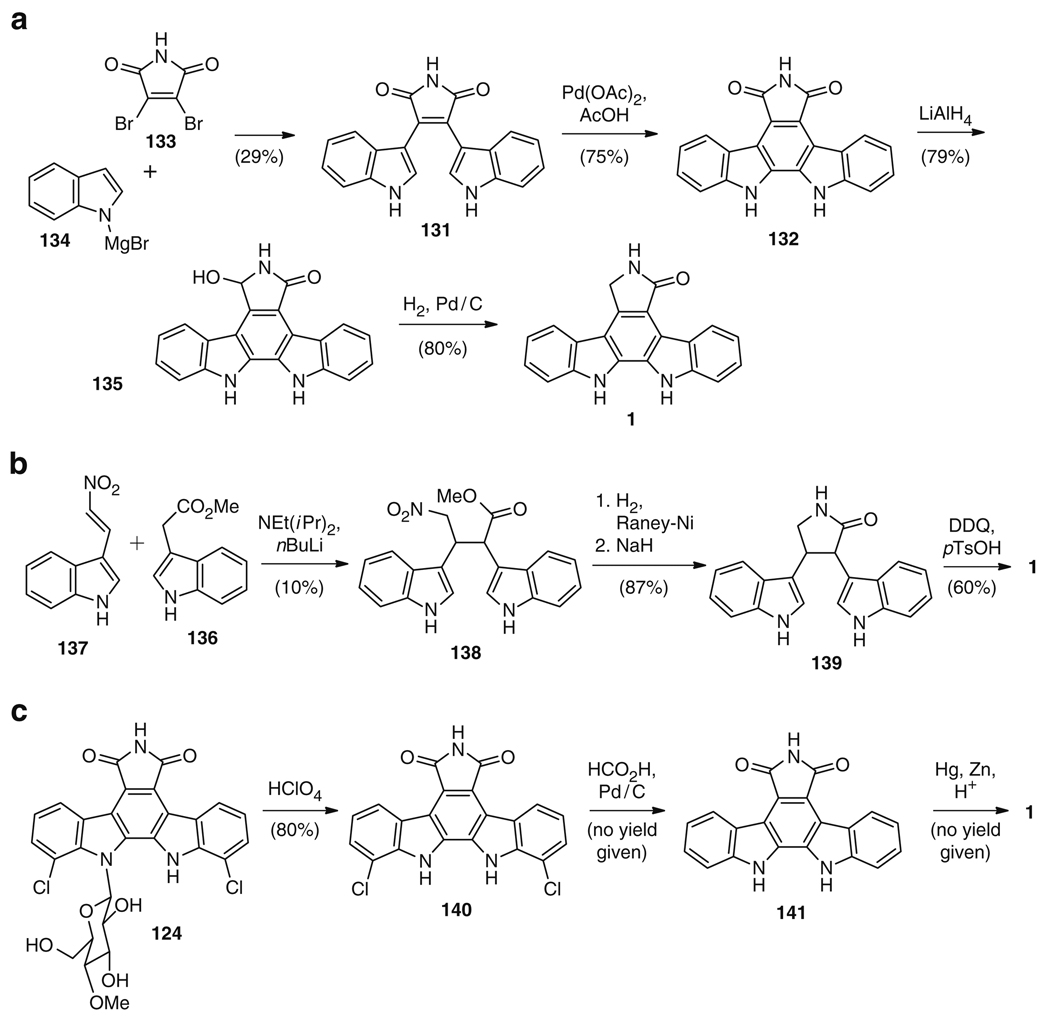

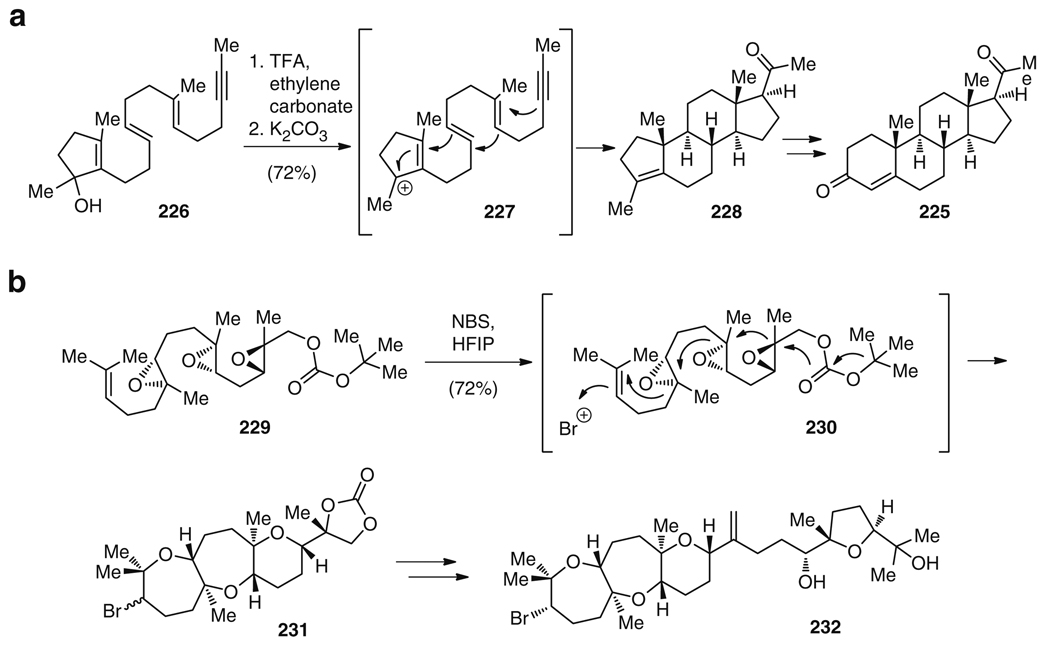

Synthetic routes to 1 are numerous and varied (Table 1). Of all synthetic routes, none use the same pathway seen biosynthetically: l-tryptophan (123) converted to indole-3-pyruvic acid imine (125), dimerized to chromopyrrolic acid (128), and oxidized to give the staurosporine aglycone (1). However, some of the synthetic routes are decidedly biomimetic. For instance, Pd-catalyzed coupling of arcyriarubin A (131) was used to generate arcyriaflavin A (132), followed by two-step reduction to give the staurosporine aglycone (1) via compound 135 (Fig. 25a) [7–9]. In Hill’s synthesis [7], treatment of dibromomaleimide (133) with indoylmagnesium bromide 134 directly delivered 29% of the coupling precursor 131. Compound 131 was cyclized using Pd(OAc)2 as the catalyst to give 132, which, upon two-step reduction, furnished 1 in 47% combined yield. Alternate routes to the 131 precursor have also been reported [8, 9]. While neither arcyriarubin A (131) nor arcyriaflavin A (132) are biosynthetic precursors to staurosporine (121) [153], both molecules share clear structural features with 128. Furthermore, the palladium-catalyzed aryl–aryl bond formation is analogous to the reaction catalyzed by StaP on chromopyrrolic acid (128). However, this synthetic strategy also involves over-oxidizing a precursor and then reducing the structure back to the staurosporine aglycone (1); by contrast, the biosynthetic strategy is a sequential set of oxidations, without any reductions, to give rise to 1.

Table 1.

Synthetic routes to the staurosporine aglycone (1)

| Citation(s) | Synthetic intermediate(s) | Key reaction(s) to give K252c | Yield from starting materials (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2] |  |

Condensation/photocyclization | 46 |

| [3] |  |

Intermolecular Michael addition | 5 |

| [4] |  |

Reductive cyclization | 37 |

| [5] |  |

Cycloaromatization | 25 |

| [6] |  |

Photocyclization | 25 |

| [7] |  |

Biaryl coupling | 14 |

| [10] |  |

Diels–Alder reaction/nitrene-mediated cyclization | 8 |

| [11] |  |

N-Deglycosylation/Clemmensen reduction | 80% to rebeccamycin aglycone; to stauroporinone not reported |

| [12] |  |

Zinc amalgam mediated cyclization | 13 |

| [13] |  |

Deoxygenation of nitro groups | 12 |

| [14] |  |

Oxidation/photocyclization | 10 |

Fig. 25.

A sample of synthetic routes (a–c) to the staurosporine aglycone (1) with biomimetic “features”

Another example of a partially biomimetic strategy is shown in Fig. 25b. Here the analogy is to the starting materials: two indole-containing molecules, 136 and 137, which were dimerized via formation of the same bond as seen in the reaction carried out by StaD on two molecules of indole-3-pyruvic acid imine (125). This bond – between the β-carbons of the l-tryptophan precursor (123) – once formed biosynthetically leads to 127, which spontaneously forms chromopyrrolic acid (128) in oxygen (Fig. 24). In the biosynthetic route, this reaction is between two unactivated carbons, which would seem to render it challenging, although low levels of 128 formation are seen between indole-3-acetic acid, l-tryptophan, and NH4+ without enzyme [158]. In the synthetic case, the reaction goes forward as a Michael addition of 137 to 136 to give 138 in 10% yield. Because of the wrong oxidation state of the nitrogen, direct cyclization of 138 – as seen in the spontaneous cyclization of 127 in the respective biosynthetic step – is not possible. Instead, reduction of the nitro function with Raney-Ni/H2 produced the free amine, which was cyclized using NaH to give 139. Final oxidative cyclization with DDQ gave the product 1 in 52% yield from 138 (Fig. 25b) [3]. Again, this synthesis has features that are biosynthetically reminiscent – first, the use of two indole containing precursors that will each provide either the “left” or the “right” side of the final product, as seen biosynthetically, and second, the closure of the upper (eventually pyrrole) ring prior to aryl–aryl coupling to give the central ring of the structure.

Finally, a “reverse” biomimetic strategy can be seen from using rebeccamycin (124), a natural product produced at approximately 700 mg L−1 of culture [11], as a starting material. As described above, the biosynthetic routes to both 124 and 121 are closely related, particularly between the aglycone portions of the molecules. The synthesis of K252c (1) from rebeccamycin (124) was accomplished by initial cleavage of the sugar from the core structure to give the rebeccamycin aglycone, dichloro arcyriaflavin A (140), in 80% yield. Pd/C-catalyzed dechlorination gave rise to rebeccamycin aglycone (141), which after Clemmensen reduction yielded 1 (Fig. 25c) [11].

Other synthetic strategies have nothing in common with the biosynthetic route. A particularly creative synthesis was presented by the research group of Moody, who aimed to use no protecting groups on the nitrogens [10]. All atoms of the staurosporine aglycone scaffold were incorporated from the beginning by condensation of 142, in turn derived from aldehyde 143 by formal reductive amination (58% yield), with 144 and oxalyl chloride to give 145 in 76% yield. Saponification of the ester 145 gave 146, which was transformed into 147 by lactone formation. Intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction of the benzylic double bond with the pyrone substructure in 147 accompanied by decarboxylation gave 148 in 26% yield from 145. Final cyclization to give the product 1 was achieved by treatment of 148 with triethyl phosphite (54% yield) (Fig. 26a) [10]. The only sense in which this strategy relates to a biosynthetic route is that all carbons and nitrogens present in the final structure are derived from an early coupling reaction.

Fig. 26.

A selection of synthetic routes (a–c) to the staurosporine aglycone (1) lacking biomimetic “features”

A synthetic route presented by Beccalli [4] builds up the indolo[2,3-a]carbazole portion of the molecule first. Formation of the left molecular half of 1 proceeded from indole 149 by N-protection to give 150, cleavage of the undesired carbonate group to furnish 151, and final O-triflation yielding 61% of 152. Pd-catalyzed coupling of 152 with tributyl stannate 153 delivered bisindole 154 in 89% yield. Ethoxide-mediated deprotection of both nitrogens to give 155 followed by photocyclization of the central ring led to 156, which was – in a single step – transformed into the desired product 1 by reduction of the cyano group using NaBH4/CoCl3 and in situ formation of the final pyrrolo ring system (Fig. 26b) [4].

Finally, the most recent, and highest-yielding strategy, is derived from a route literally perpendicular to the natural strategy: instead of dimerization using l-tryptophans (123), the bisindole portion and the pyrrole portion were fused. Specifically, 157 and 158 were coupled through a Lewis-acid catalyzed electrophilic substitution reaction to give 159. Photocyclization then resulted in generation of 1 in only two steps and 46% overall yield (Fig. 26c) [2].

The rich number of synthetic strategies to the staurosporine aglycone – which is rare among other natural products – demonstrates the fallacy of concluding strongly, for a given molecule, whether the best synthetic route is likely to be biomimetic. For the staurosporine aglycone (1), while some synthetic routes have features that are biochemically “reminiscent,” others have nothing to do with the natural route. The probable impossibility of making a completely biomimetic route in this case, though, suggests that biosynthesis and total synthesis occupy two unique niches, which might intersect but are unlikely to replace one another.

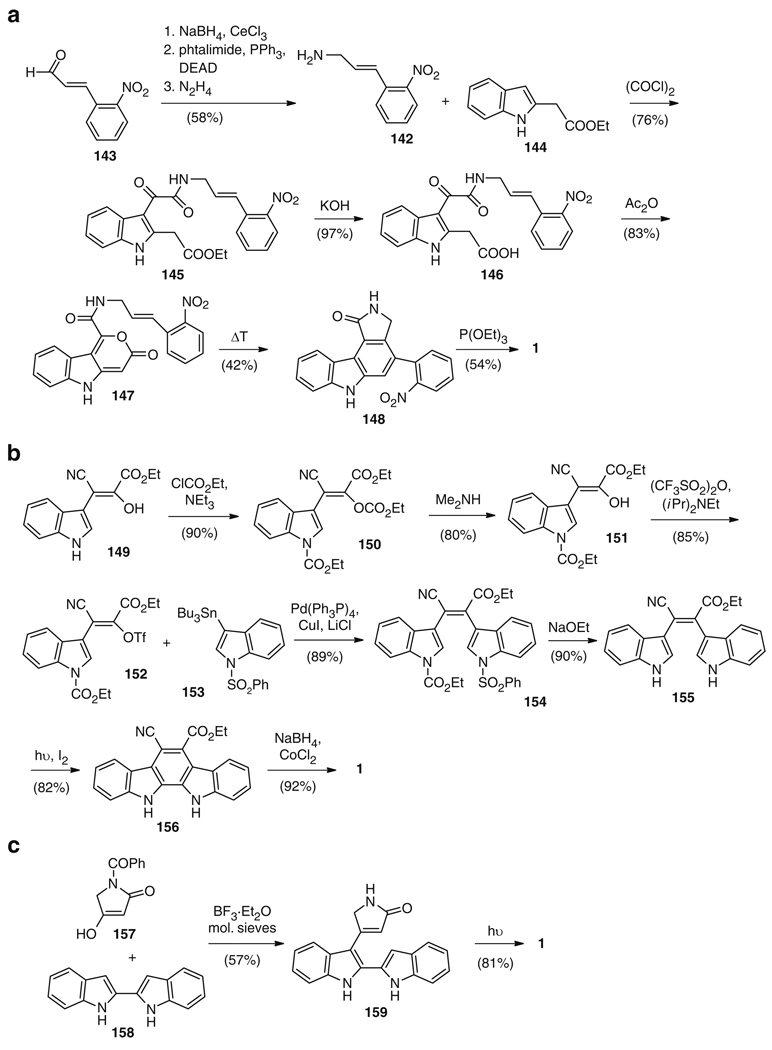

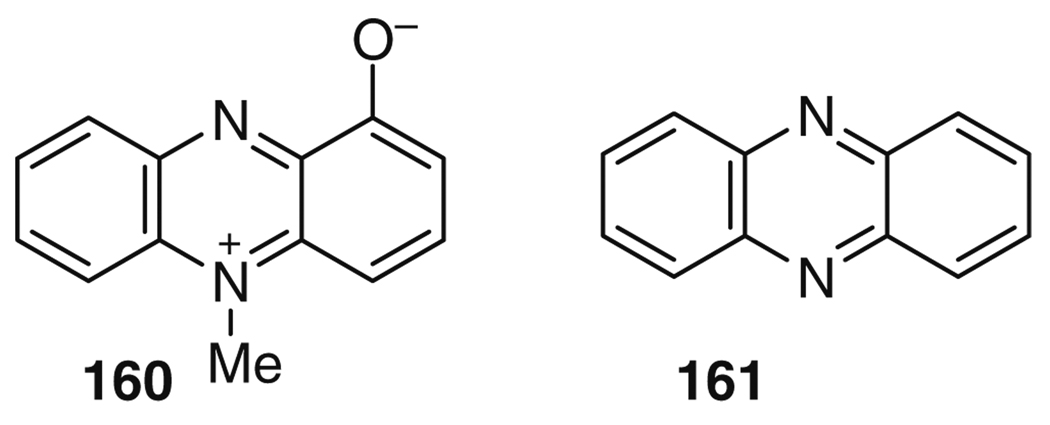

6 Phenazines: Pyocyanin

Pyocyanin (160) is a blue-colored phenazine (161) molecule produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Fig. 27). The pigment was first observed as a blue pus in the wounds of infected patients; by 1859, the pigment was isolated as a chloroform extraction of a wound dressing, and the correct structure was identified in 1938 [168]. Although pyocyanin (160) has antibiotic properties [169], its main importance to human health is as a critical virulence factor excreted by P. aeruginosa during lung infections [170] and, in particular, in lung disease in cystic fibrosis patients. Pyocyanin (160) is thought to exhibit its effects through generation of reactive oxygen species, which target, among others, the vacuolar ATPase [171], and lead to the induction of neutrophil apoptosis [172], inhibition of uptake of apoptotic cells by macrophages [173], and other effects [174]. Interestingly, the function of pyocyanin (160) in the producing bacterium is now under active investigation, and the postulated roles include intracellular redox balance in the absence of other electron acceptors [175], promoting mineral reduction [176], functioning as a terminal signaling molecule in the quorum sensing network [177], and controlling colony biofilm physiology [178].

Fig. 27.

Pyocyanin (160) is a phenazine (161) natural product

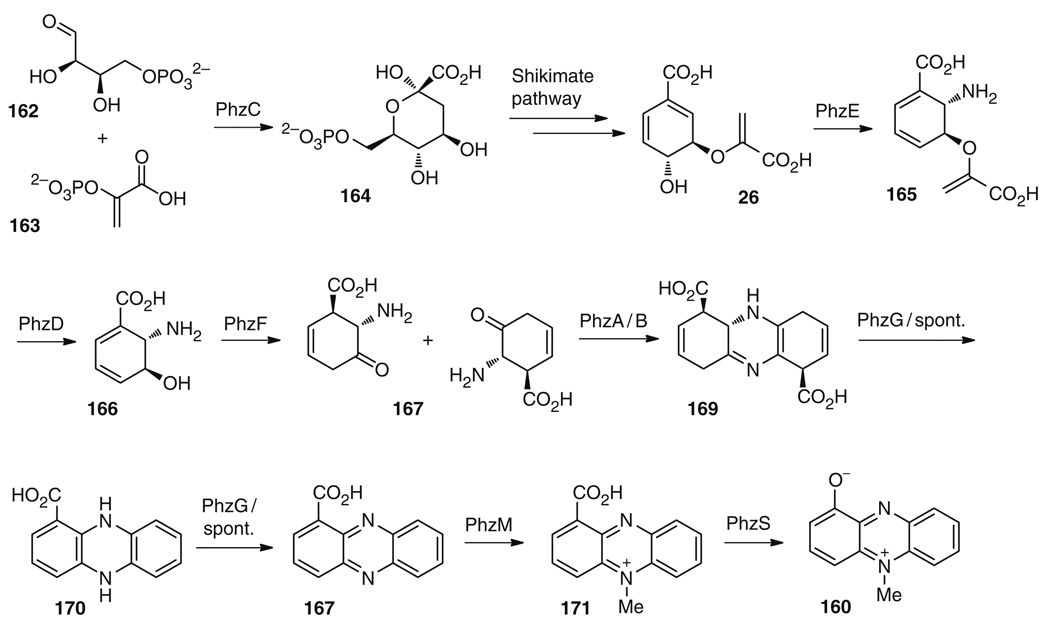

The biosynthetic route to pyocyanin (160) has been studied for decades. As in the case of K252c (1), described above, no single, one-pot, total biosynthesis has been reported for 160; however, each of the biosynthetic enzymes required for its production has been characterized in vitro. All known phenazine natural products which share a core phenazine structure are thought to derive from a largely conserved biosynthetic pathway, with the possible exception of the phenazine from Methanosarcina mazei Gö1 [168, 179], whose genome lacks the “usual” phenazine biosynthetic gene cluster. Early isotopic labeling studies established that pyocyanin (160) is derived from the shikimic acid pathway [180], and more recent work has resulted in the sequencing of the biosynthetic gene clusters for phenazines in a variety of bacterial species [181–186].

Pyocyanin (160) is derived from the shikimate pathway, and one protein, PhzC, is equivalent to enzymes that catalyze the first step in this pathway, converting erythrose 4-phosphate (162) and phosphoenolpyruvic acid (163) to 3-deoxy-darabinoheptulosonate 7-phosphate (164) (Fig. 28). The equivalent enzyme in the shikimate pathway is thought to be feedback regulated, and PhzC is likely to shunt intermediates toward the shikimate pathway in preparation for pyocyanin (160) biosynthesis when the shikimate enzyme is inactive [181]. Subsequent enzymes in the shikimate pathway, which construct chorismic acid (26), are thought to be constitutively active [187], and there are no “replacement” enzymes for them in the pyocyanin biosynthetic route.

Fig. 28.

Overall biosynthetic route to pyocyanin (160)

Chorismic acid (26), thus, represents the first “divergence” point of pyocyanin from other biosynthetic pathways. The first authentic pyocyanin biosynthetic enzyme is PhzE, which has sequence similarity to anthranilate synthases, which generate anthranilate from chorismate. PhzE is thought to catalyze the conversion of chorismic acid (26) to amine 165. Compound 165 is in turn a substrate for PhzD, an isochorismatase that catalyzes the hydrolysis of the vinyl ether to 166 and pyruvate [188, 189].

Incubation of PhzF, PhzA, PhzB, and PhzG converts 166 to phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (167). The specific roles of each enzyme are still not fully elucidated; however, a series of impressive studies, which include crystal structures of each enzyme, have begun to reveal the chemistry involved in the conversion [190–193]. While the highest rates of conversion are achieved with all four enzymes, interestingly, PhzF alone is able to generate, at low levels, the desired product 167. The mystery of why PhzF can generate 167 on its own was resolved when it was realized that PhzF catalyzed the formation of the ketone 168, a molecule that can, in turn, undergo spontaneous dimerization, decarboxylation, and oxidation to give low levels of 167 [190, 192]. When PhzA/B are present, however, the reactions are dramatically accelerated. PhzA/B, which are highly related enzymes (80% identity), form a heterodimer and accelerate the head-to-tail dimerization of two molecules of 168, giving rise to a tricyclic intermediate thought to be dicarboxylic acid 169. This molecule is also likely to be oxygen-sensitive, and can spontaneously decarboxylate to give 170 [193]. Finally, PhzG, which has structural similarity to other known flavin-dependent oxidases, is thought to catalyze the oxidation of a tricyclic intermediate such as 170 to 167 through unknown mechanisms [191]. Regrettably, however, its activity with any proposed intermediates still remains to be established, and the possibility that some of the chemistry is spontaneous still remains.

The final conversions of 167 to 160 are catalyzed by PhzM and PhzS, two enzymes that are likely to interact, at least transiently, during catalysis. PhzM is related structurally to SAM-dependent methyltransferases, and it is thought to catalyze N-methylation of 167 to give N-methyl-phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (171) [194]. PhzS, a structural relative of flavin-dependent hydroxylases, is thought to catalyze the decarboxylation and oxidation of 171 [195]. However, while activity for the two-enzyme reaction has been verified in vitro, experimental proof for either single reaction is not yet available. PhzM is inactive by itself with 167 and only reacts when PhzS is also present [194]. The reaction of PhzS alone has been similarly challenging to determine; the putative substrate 171 is unstable and therefore has not yet been tested [195]. The currently available evidence suggests that PhzM and PhzS form at least a transient complex during catalysis, and that the intermediate 171, generated by PhzM from 167, is shuttled to PhzS, where flavindependent decarboxylation and oxidation reactions occur to give rise to the final product 160.

Overall, the biosynthesis of 160 is characterized by the dimerization of 168 to give the central structure of the molecule. This head-to-tail dimerization strategy is efficient, using the same substrate twice, and is a sensible route, given the existence of the shikimate pathway, which provides, in turn, a precursor to 168. An analogous dimerization route can be seen for the biosynthesis of K252c (1), described in Sect. 5, where two molecules of indole-3-pyruvic acid imine (125), derived in turn from l-tryptophan (123), are dimerized to give an intermediate that leads to chromopyrrolic acid (128). In both cases, the monomer precursors, either 168 or 125, serve as both nucleophiles and electrophiles, and are activated to react by the presence of the appropriate enzymes.

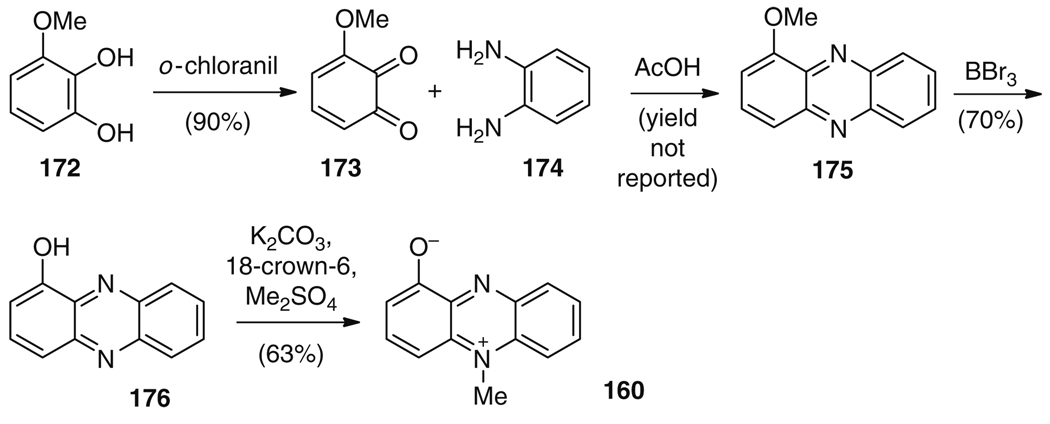

Interestingly, the synthetic route to 160 utilized a similar strategy of condensing the two outer rings of the desired product to give the central heterocycle. The synthesis commenced with diol 172, which was oxidized to furnish 3-methoxy-1,2-benzoquinone (173) in 90% yield. Condensation of electrophile 173 with 174 delivered phenazine 175, which was O-deprotected to give 176 and selectively N-methylated to furnish the natural product 160 (Fig. 29) [196, 197]. As in the biosynthetic route, this synthetic strategy utilizes a key coupling reaction of 173 and 174 to give 175. Here, however, the nucleophilic nitrogens are all located in one molecule 174 whereas the electrophilic carbonyl oxygens are contained entirely in a separate compound 173 [194, 195]. In the case of pyocyanin (160), the synthesis forms the desired product from simple starting materials in a very concise way. The comparison of the biosynthesis and synthesis of 160 thus evidences a striking example for a natural product which can more effectively be prepared by chemists than by nature.

Fig. 29.

Synthetic route to pyocyanin (160)

7 Enterocin- and Wailupemycin-Type Polyketides

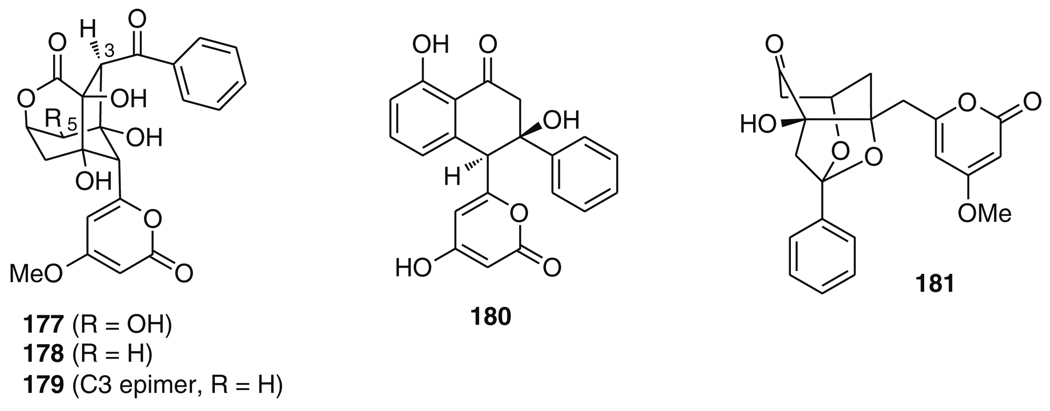

Another chemically and biosynthetically intriguing suite of secondary metabolites is produced by “Streptomyces maritimus.” The main product is the structurally complex enterocin (177) (Fig. 30) [198], which has also been isolated from terrestrial Streptomyces [199–201] and from an ascidian [202]. S. maritimus also produces simple analogs of 177, differing only in the oxygenation pattern as in 5-deoxyenterocin (178), or in the absolute configuration as in 3-epi-5-deoxyenterocin (179). In addition, the organism biosynthesizes the wailupemycins. The molecular structures of these compounds range from relatively simple α-pyrones like wailupemycin D (180) to the complex tricyclic acetal wailupemycin B (181). The unusual molecular architectures of enterocin (177) and wailupemycin B (181), and the bacteriostatic properties of these metabolites against E. coli and species within the genera Corynebacterium, Proteus, Sarcina, and Staphylococcus [198, 199], have triggered investigations of their biosynthesis at the genetic and biochemical level, as well as total synthetic efforts.

Fig. 30.

Selection of enterocin- and wailupemycin-type natural products produced by S. maritimus

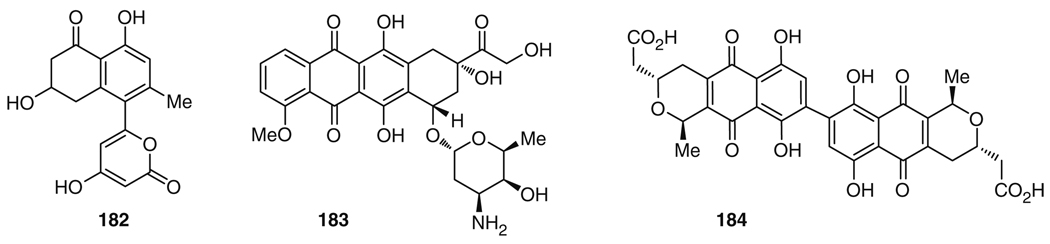

The α-pyrone moiety observed in 177 and in the wailupemycins constitutes a typical structural motif of compounds produced by genetically engineered iterative type II polyketide synthase (PKS) systems, such as in mutacin (182) (Fig. 31) [203]. These PKSs usually catalyze the formation of (poly)cyclic aromatic natural products such as doxorubicin (183) and actinorhodin (184) [204, 205]. The enzymes involved in the formation of aromatic PKS metabolites are related to type II fatty acid synthases. At least three elements are necessary to render such PKS systems functional: two β-ketosynthase subunits, KSα and KSβ, and an acyl carrier protein (ACP). In typical type II PKS systems, these genes are accompanied by cyclases and aromatases which funnel the nascent highly reactive poly-acetate precursor into the desired aromatic PKS products. The latter can be further functionalized by tailoring enzymes which can, for example, catalyze oxidation, alkylation, and glycosylation reactions. The apparent structural similarity of some known iterative type II PKS shunt products with the observed α-pyrones of S. maritimus suggested using a type II PKS based genetic probe to identify the enterocin biosynthesis cluster. These investigations led to the discovery of the enterocin biosynthetic machinery enc consisting of 20 putative open reading frames (ORFs) in a contiguous 21.3-kb region of the cosmid [206, 207].

Fig. 31.

Structures of mutacin (182), doxorubicin (183), and actinorhodin (184)

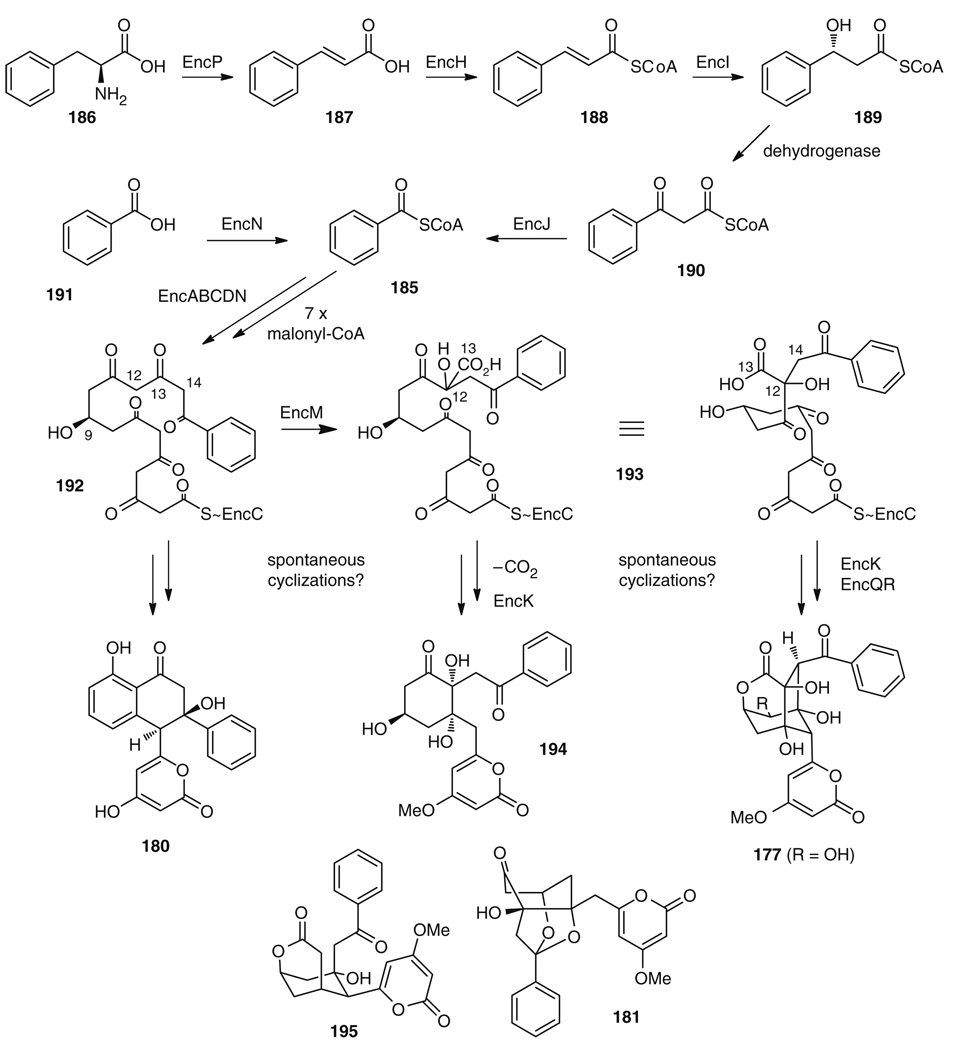

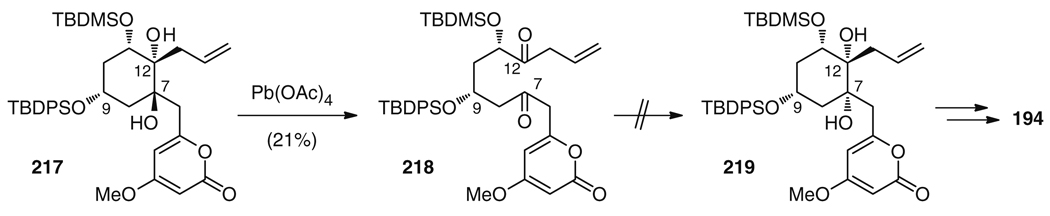

The enc cluster contains four genes (encH, encI, encJ, encP) involved in the biosynthesis of the unusual benzoyl-CoA (185) starter from phenylalanine (186) via a plant-like β-oxidation mechanism (Fig. 32) [208–210]. This pathway is initiated by the unique phenylalanine ammonia-lyase EncP [211], which catalyzes the generation of cinnamic acid (187) from 186. The cinnamate-CoA ligase EncH then forms 188, which is oxidized by action of the cinnamoyl-CoA hydratase EncI to give 3-hydroxy-3-phenylpropionyl CoA (189). The required dehydrogenase for the following oxidation of 189 to diketone 190 is missing in the enc cluster and is thus thought to be entirely supplied from primary metabolism. Subsequently, the keto thiolase EncJ catalyzes the last step to the starter unit 185. The benzoate-CoA ligase EncN additionally facilitates the use of exogenic benzoic acid (191) in the pathway. The enc minimal PKS, EncABC, which catalyzes the iterative assembly of the polyketide chain, comprises the typical KSα (EncA) and KSβ (EncB) ketosynthase subunits and an ACP (EncC). The latter is primed with 185 in a type II NRPS-like fashion by EncN [212]. Loading of the malonyl-CoA extender units is presumably catalyzed by the malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase, EncL, but can be complemented by enzymes from primary metabolism. In addition, the production of wailupemycins or enterocins requires the presence of the ketoreductase (KR) EncD, which catalyzes regioselective reduction (possibly of the still growing polyketide chain) [213] to furnish 192, the central biosynthetic precursor of the enc pathway (Fig. 32). Spontaneous cyclization of 192 gives rise to wailupemycin D (180). In contrast to all other type II PKS gene sets, the enc cluster does not harbor any cyclases or aromatases, but a flavin-dependent oxygenase EncM. This enzyme putatively catalyzes α-oxidation at C12 of 192 and Favorskii-type rearrangement to give 193 [214]. Cyclization of 193, followed by selective O-methylation of the α-pyrone system, by the methyltransferase EncK, opens the pathway to wailupemycins A (194) and, with additional loss of CO2, to 181 and wailupemycin C (195). On the other hand, spontaneous cyclization and ester formation, followed by EncK mediated O-methylation and oxygenation at C5 by EncQR furnishes 177.

Fig. 32.

Biosynthetic pathway leading to enterocins and wailupemycins

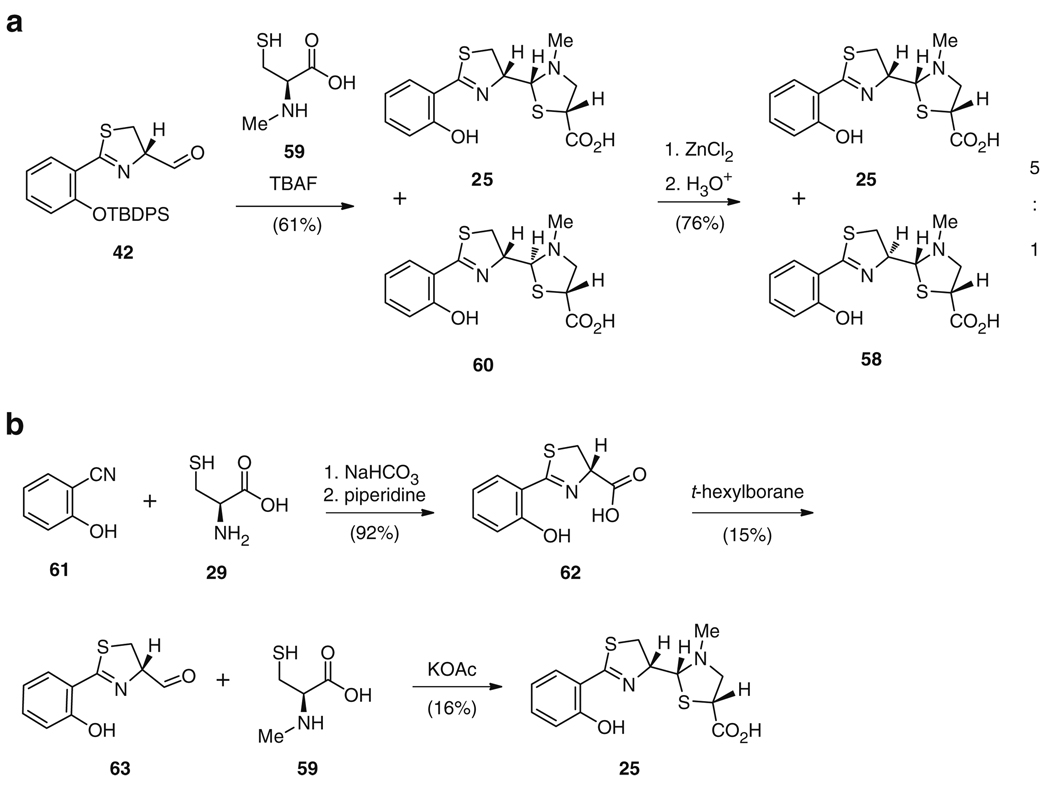

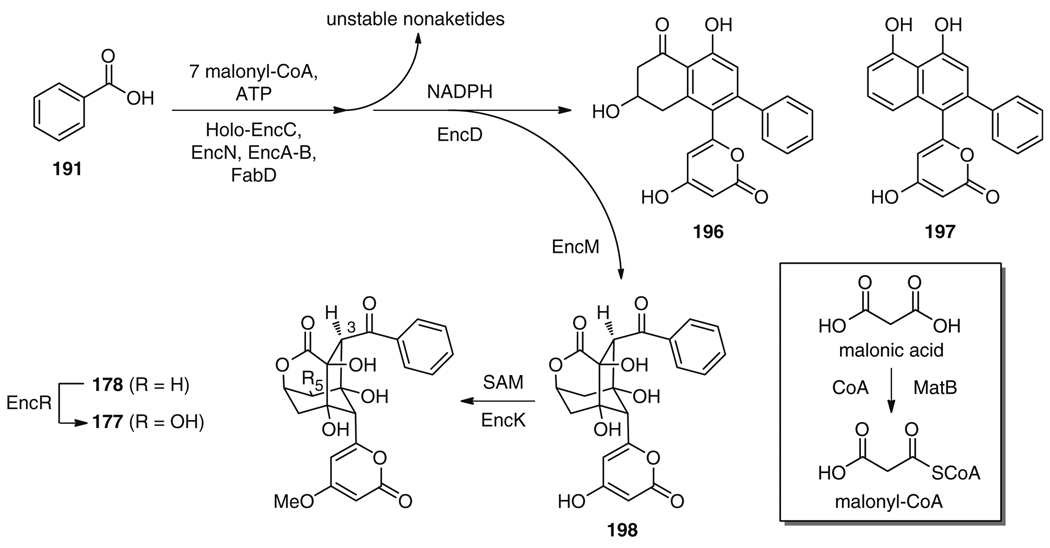

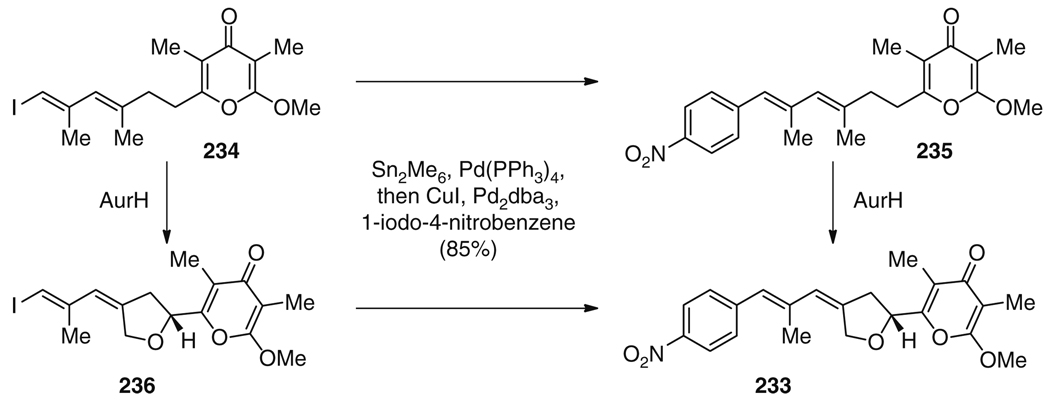

The exact order of biosynthetic transformations was firmly established by the enzymatic total biosynthesis of enterocin (177) [215]. Incubation of an EncA–EncB heterodimer, holo-EncC, and a malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase from Streptomyces glaucescens (SgFabD) [216] with malonyl-CoA yielded several highly unstable nonaketides of unknown structure (Fig. 33). The formation of wailupemycin-type compounds was achieved by addition of the ketoreductase EncD together with its cofactor NADPH. With this set of enzymes the natural products wailupemycins F (196) and G (197) [217] were produced as the main products. Addition of the “favorskiiase” EncM to the enzymatic mixture allowed for the production of desmethyl-5-deoxyenterocin (198), along with 196 and 197. EncM, thus, not only catalyzes the oxidative rearrangement, but also initiates two subsequent aldol reactions and heterocycle formations [214], which leads to the generation of a remarkable six chiral centers with perfect regio- and stereocontrol starting from a highly reactive, linear and achiral precursor. Production of 5-deoxyenterocin (178) was achieved by adding the methyltransferase EncK and SAM to the above enzyme mixture. Final oxidation at C5 succeeded using the P450 hydroxylase EncR, ferredoxin, ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase, and catalase. High turnover rates for this hydroxylation to 177, however, were only achieved after an extractive workup of 178 and renewed reaction setup. This can be attributed to the inhibitory effect of SAM on cytochrome P450 enzymes [218]. Adding CoA and the Rhizobium leguminosarum malonyl-CoA synthase MatB [219] directly to the above enzyme mixture allowed for the substitution of up to 90% malonyl-CoA by malonic acid without lowering chemical yields (Fig. 33).

Fig. 33.

One-pot total in vitro biosynthesis of enterocin (180) and wailupemycin F (199) and G (200)

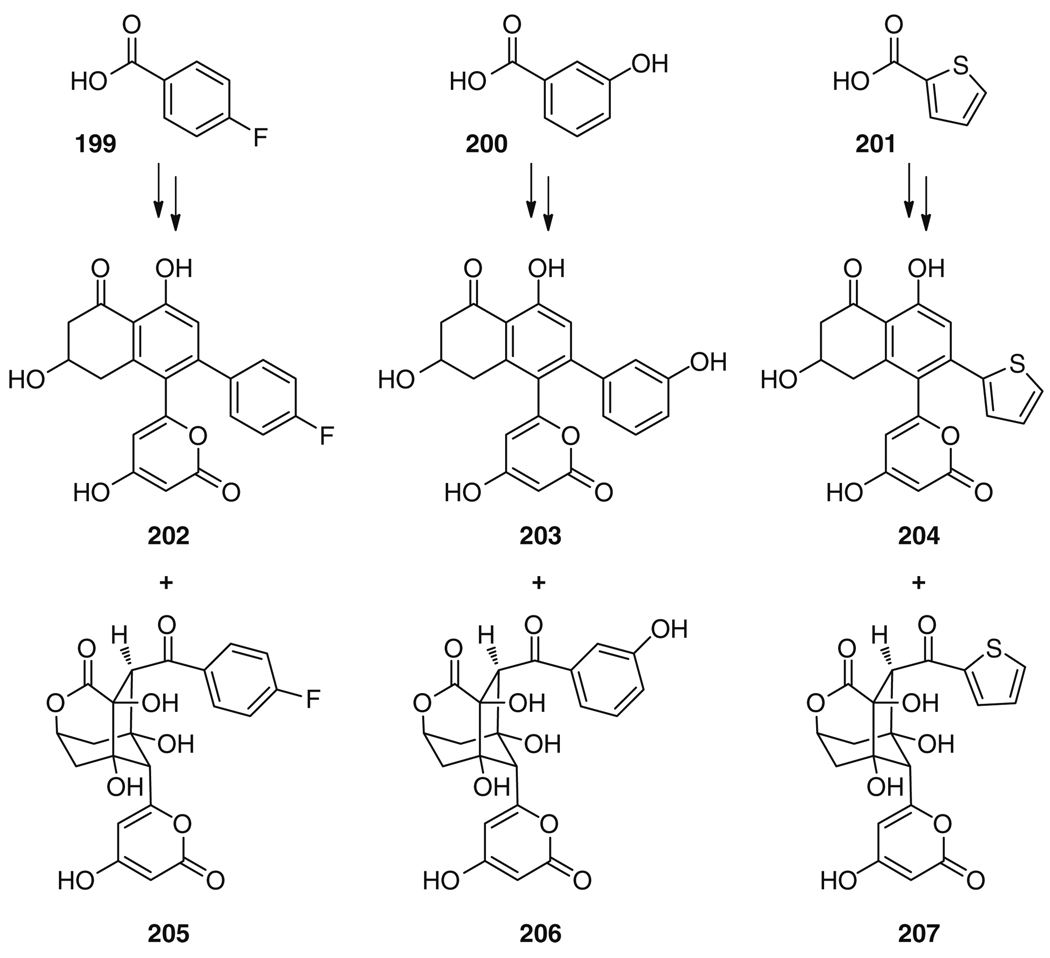

Using this chemo-biosynthetic toolbox consisting of EncA/B, EncC, EncD, EncK, EncM, EncN, EncR, SgFabD, and MatB in combination with the respective cofactors, as well as benzoic and malonic acid as carbon sources, the in vitro total synthesis of enterocin (177) was accomplished in a remarkable 25% overall yield. The construction of ten C–C bonds, five C–O bonds, and seven chiral centers to give the highly complex tricyclic structural framework of 177 was achieved using seven equivalents malonyl-CoA and two equivalents NADPH per 191, SAM, and ATP [215]. The utility of this total biosynthesis was recently further expanded by using a series of halogen and hydroxyl-substituted benzoic acid derivatives, such as 199 and 200, as well as heterocyclic aromatic precursors like 201, as unnatural starter units to produce novel wailupemycin and enterocin derivatives, such as 202–204 and 205–207, respectively (Fig. 34) [220]. This purely enzymatic approach to generate molecular diversity eliminates unpredictable factors that are usually associated with more classical in vivo mutasynthetic experiments, such as precursor uptake, toxicity, transport, and metabolism. Consequently, this in vitro biosynthesis method resulted in the successful preparation of many more structural variants of wailupemycins and enterocins than previous related in vivo work [221].

Fig. 34.

Selection of novel wailupemycin 202–204 and enterocin analogs 205–207 generated by in vitro biosynthesis using unnatural starter units 199–201

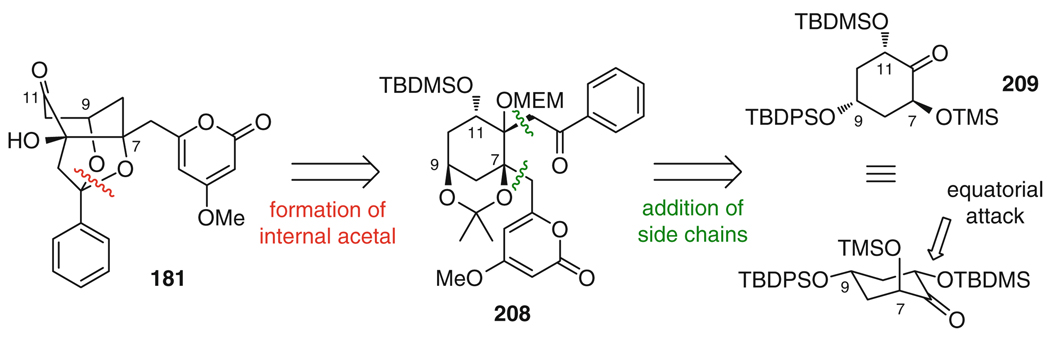

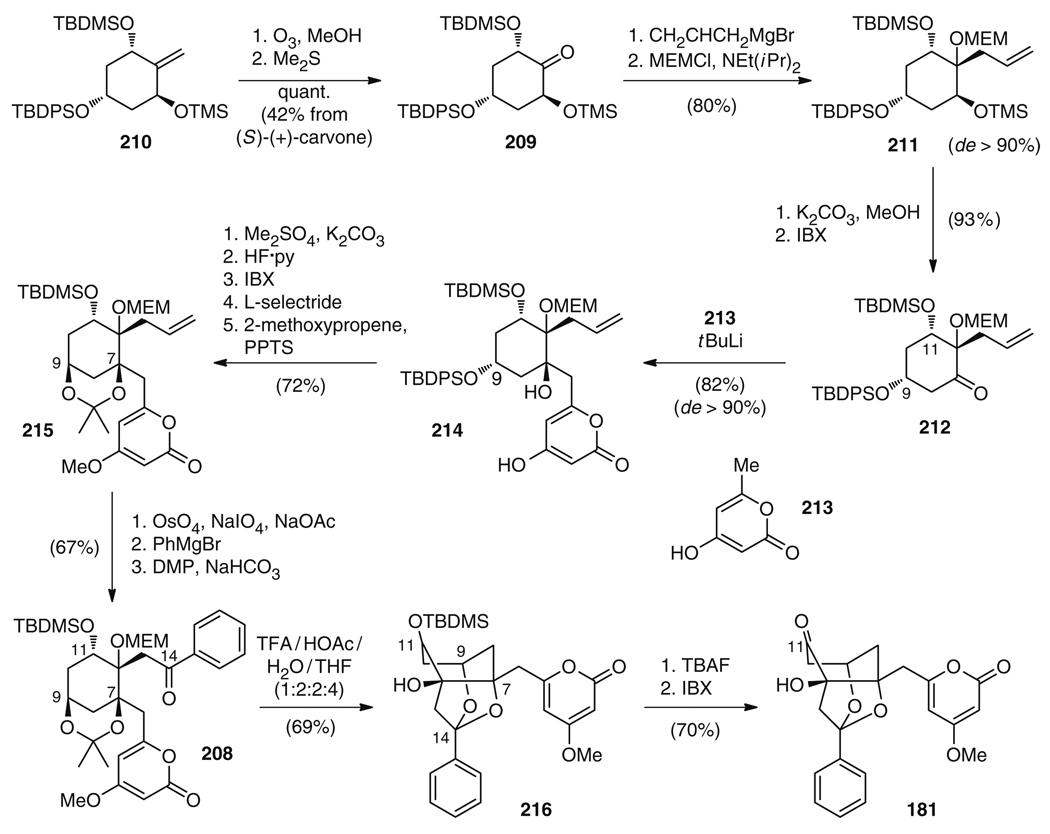

The first and so far only total synthesis of a member of the wailupemycin family, wailupemycin B (181), was reported by the Bach group [222, 223]. In their retrosynthetic considerations, they aimed for an initial stereoselective generation of the central cyclohexane ring system which would allow for the flexible attachment of the peripheral substituents at a late stage. This strategy would facilitate the preparation of structural analogs of wailupemycin B for use in investigations of structure–activity relationships (SARs). A key precursor of this synthetic strategy was cyclohexane 208, which is accessible from ketone 209 (Fig. 35). It is interesting to note that in order for the envisioned nucleophilic attack at C12 to proceed from the desired side when installing the C12 side chain, the configuration at C9 of 209 had to be inverted as compared to the natural product. The reason is that bulky groups at C9 and C11 adopt equatorial positions, thus locking 209 into a chair conformation, which is predominantly attacked from the face delivering the correct diastereomer.

Fig. 35.

Retrosynthetic analysis of wailupemycin B (181) by the Bach group