Abstract

Fumarate hydratase catalyzes the stereospecific hydration across the olefinic double bond in fumarate leading to L-malate. The enzyme is expressed in mitochondrial and cytosolic compartments, and participates in the Krebs cycle in mitochondria, as well as in regulation of cytosolic fumarate levels. Fumarate hydratase deficiency is an autosomal recessive trait presenting as metabolic disorder with severe encephalopathy, seizures and poor neurological outcome. Heterozygous mutations are associated with a predisposition to cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas and to renal cancer. The crystal structure of human fumarate hydratase shows that mutations can be grouped into two distinct classes either affecting structural integrity of the core enzyme architecture, or are localized around the enzyme active site.

An interactive version of this manuscript (which may contain additional mutations appended after acceptance of this manuscript) may be found on the SSIEM website at: http://www.ssiem.org/resources/structures/FH.

Introduction

Fumarate hydratase (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase are two integral enzyme components of the Krebs cycle, and besides their essential role in the TCA cycle, can act as tumour suppressors (King et al. 2006). The FH gene codes for fumarate hydratase (or fumarase; EC 4.2.1.2), which catalyzes the stereospecific, reversible hydratation of fumarate to L-malate. The FH gene localized at 1q42.1 codes for differentially processed, but sequence-wise identical cytosolic and mitochondrial forms. Whereas the mitochondrial enzyme is part of the TCA cycle, the cytosolic form is thought to utilize fumarate derived from different sources. Deficiency in FH activity causes an impaired energy production by interrupting the flow of metabolites through the Krebs cycle. Accumulation of fumarate is thought to competitively inhibit 2-oxo-glutarate dependent dioxygenases that regulate hypoxia inducible factor (HIF), thus activating oncogenic hypoxia pathways (Ratcliffe, 2007).

Due to their essential role in energy production, enzyme deficiencies result in early onset of severe encephalopathy (Kerrigan et al. 2000). Accordingly, autosomal recessive fumarate hydratase deficiency (FHD) caused by mutations in the FH gene results in fumaric aciduria, and common clinical features observed are hypotonia, failure to thrive, severe psychomotor retardation, seizures, facial dysmorphism and brain malformations. Interestingly, whereas homozygous FH mutations predispose to fumaric aciduria, several heterozygous FH mutations are known to be involved in the autosomal dominant syndrome of multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomata (MCUL1) (Tomlinson et al. 2002). Affected individuals develop benign smooth muscle tumours of the skin, and females develop fibroids of the uterus. When co-existing with an aggressive form of renal cell carcinoma (papillary renal type II cancer or renal collecting duct cancer) it is also known as hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer (HLRCC) syndrome. In MCUL1/HLRCC germline mutations in FH are detected in the majority of the screened cases. To date, 107 variants have been described, of which 93 are thought to be pathogenic (Bayley et al. 2008). The most common types are missense mutations (57%), followed by frameshift and nonsense mutations (27%), as well as diverse deletions, insertions and duplications.

Here we present the crystal structure of human fumarase at 1.95 Å resolution and summarize structure-activity correlation between observed mutations and clinical phenotypes.

Materials and methods

Expression, purification & crystallization

DNA fragment encoding the fumerase domain of human FH (aa 44-510; GenBank entry 19743875) was subcloned into pNIC28-Bsa4 vector incorporating an N-terminal His6-tag. The plasmid was transformed into BL21(DE3)-pRARE, cultured in Terrific Broth at 37°C, and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG overnight at 18°C. Cells were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM K-phosphate pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP), centrifuged to remove cell debris, and the supernatant was purified by Nickel affinity (HisTrap Crude FF) and size exclusion (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex S200) chromatography. Purified protein was concentrated to 12.6 mg/ml and stored in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5% (w/v) glycerol and 0.5 mM TCEP at -80°C. Crystals were grown by vapour diffusion at 20°C in sitting drops mixing 150 nl protein and 150 nl reservoir solution containing 20% (w/v) PEG 3350, 0.2 M sodium acetate, 10% (w/v) ethylene glycol and 100 mM Bis-Tris propane pH 7.5. Crystals were cryo-protected in mother liquor containing 25% (w/v) glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Data collection & structure determination

Diffraction data to maximum resolution of 1.95 Å were collected on beamline X10A at the Swiss Light Source, and processed using the CCP4 Program suite (CCP4, 1994). FH crystallized in the trigonal space group P3221 (a = 180.5 Å, b = 180.5 Å, c = 114.6 Å, α = 90o, β = 90o, γ = 120o) with four molecules in the asymmetric unit. The structure of FH was solved by molecular replacement with PHASER (McCoy et al. 2005), using the yeast fumerase structure as search model (PDB code 1YFM). Initial automated model building was performed with ARP/wARP (Perrakis et al. 1999). This is followed by cycles of iterative manual model building using COOT (Emsley & Cowtan 2004) and restrained refinement using REFMAC5 with TLS parameters (Murshudov et al. 1997). The final structure was deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) under accession code 3E04 (Table 1).

Table 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

|---|---|

| Space group | P3221 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 188.5, 188.5, 114.6 |

| γ | 120o |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.000 |

| Resolution (Å)* | 25.0 – 1.95 (2.06 – 1.95) |

| Rmerge (%)* | 0.141 (0.732) |

| I/σI* | 9.7 (2.0) |

| Completeness (%)* | 99.3 (96.8) |

| Redundancy* | 6.2 (5.0) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 41.27 – 1.90 |

| No. reflections | 168629 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 19.7/24.4 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 13160 |

| Ligand/ion | 12 |

| Water | 655 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Main-chain | 24.88 |

| Side-chain and water | 25.91 |

| RMS deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.201 |

| PDB code | 3E04 (doi:10.2210/pdb3e04/pdb) |

* Numbers in parentheses represent data in the highest resolution shell.

Results and discussion

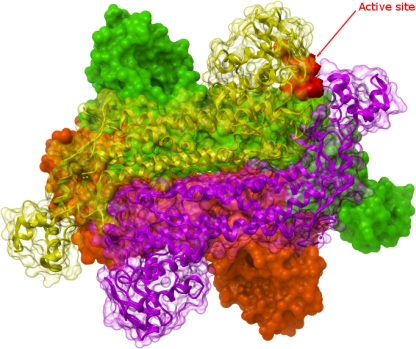

Fumarases are divided into two distinct groups. Class I fumarases are iron-dependent iron-sulfur cluster containing, dimeric enzymes, whereas the class II enzymes, including human and other eukaryotic fumarases, are homotetrameric enzymes with a molecular mass of about 200 kDa. Class II fumarases are evolutionarily highly conserved enzymes, e.g. the pairwise identity between E. coli and human fumarase is about 60%. Every monomer exhibits a typical tridomain structure, with a central domain involved in subunit interaction, thus forming a typical bundle comprised of 20 α-helices (Fig. 1A). Previous crystallographic analyses have revealed two distinct sites (A and B) in E. coli fumarase that can bind carboxylic acids. Site A is formed from three different monomer chains and likely to be the catalytic site, whereas site B is thought to allosterically regulate activity (Rose and Weaver 2004).

Fig. 1.

Ribbon/surface diagram of human fumarate hydratase illustrating the tetrameric assembly of class II fumarases. Molecular surface representation is used to convey the overall shape of each monomer as well as the tetrameric assembly. Each monomer has been coloured distinctively, to facilitate visualization. Two monomers are represented using semi-transparent surfaces, to highlight the fold (represented as ribbons). One of the active sites is highlighted in red, showing contribution of three distinct subunits. The figures were generated using the program ICM (www.molsoft.com)

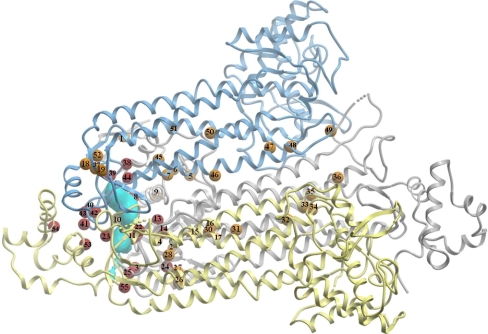

A previous study correlated 27 distinct missense mutations to the E. coli fumarase structure (Alam 2005b), since then the list of mutations has doubled. To this end, 55 missense mutations in the human fumarase gene are now described. Here we correlate this updated list of mutations to fumarase deficiency, MCUL1 and HLRCC syndrome (Table 2) by using the human fumarase structure. Although not all of these novel mutations have been biochemically characterized, previous results suggest that FH activity is related to HLRCC (Alam 2005a), although other environmental or genetic factors likely play a role in the etiology of the disease. The clustering of mutational “hotspots” suggests enzyme activity relationships to phenotypic appearances. Figure 2 illustrates the clustering of FH mutations observed in FHD, MCUL1 and HLRCC. The large majority of mutations are located at evolutionarily highly conserved positions (Table 2) indicating that these mutations likely affect stability and/or activity of the enzyme. Two major clusters of mutations are observed; one is likely to affect structural integrity of the enzyme by interrupting inter or intrasubunit interactions (indicated in yellow in Fig. 2), whereas the other mutations are located around the active site and likely directly affect activity.

Table 2.

Mutations observed in the human fumarase gene and association to disease. Abbreviations: CL: cutaneous leiomyoma; FHD: fumarate hydratase deficiency; HLRCC: hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer; LCT: Leydig cell tumors; MCUL: multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomata; OMC: ovarian mucinous cystadenoma; RCC: renal cell carcinoma; STS: soft tissue sarcoma; UL: uterine leiomyomas; ULMS: uterine leiomyosarcoma

| # | Mutation site | Mutated residue | Protein change | DNA change | Exon | Conservation | Localization | Reference | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arg51 | Glu | R51E | c.152 G > A | 2 | Conserved | Surface | (Kiuru et al. 2002) | STS |

| 2 | Arg101 | Pro | R101P | c.302 G > C | 3 | Semi-conserved | Surface | (Chan et al. 2005), (Heinritz et al. 2008) | HLRCC |

| 3 | Asn107 | Thr | N107T | c.320A > C | 3 | Conserved | Active site | (Tomlinson et al. 2002), (Alam et al. 2005a), (Carvajal-Carmona et al. 2006) | MCUL, LCT |

| 4 | Ala117 | Pro | A117P | c.349 G > C | 3 | Semi-conserved | Near active site | (Tomlinson et al. 2002) | MCUL |

| 5 | Leu132 | Ser | L132S | c.395 T > C | 4 | Semi-conserved | Surface | (Wei et al. 2006) | HLRCC, reduced FH activity |

| 6 | His135 | Arg | H135R | c.404A > G | 4 | Semi-conserved | Surface | (Chuang et al. 2005) | MCUL |

| 7 | Gln142 | Lys | Q142K | c.424 C > A | 4 | Conserved | Near active site | (Badeloe et al. 2006) | MCUL |

| 8 | Ser158 | Ile | S158I | c.473 G > T | 4 | Semi-conserved | Near active site | (Martinez-Mir et al. 2003) | MCUL |

| 9 | Arg160 | Gly | R160G | c.478A > G | 4 | Conserved | Surface | (Wei et al. 2006) | MUCL, reduced FH activity |

| 10 | Pro174 | Arg | P174R | c.521 C > G | 4 | Not conserved | Surface | (Alam et al. 2005b), (Zeng et al. 2006), (Pollard et al. 2005) | FHD |

| 11 | His180 | Arg | H180R | c.539A > G | 4 | Semi-conserved | Active site | (Tomlinson et al. 2002), (Alam et al. 2005b) | MUCL |

| 12 | Gln185 | Arg | Q185R | c.554A > G | 4 | Conserved | Active site | (Tomlinson et al. 2002) | MCUL |

| 13 | Ser187 | Leu | S187L | c.560C > T | 5 | Conserved | Active site | (Toro et al. 2003) | MCUL |

| 14 | Asn188 | Ser | N188S | c.563A > G | 5 | Conserved | Active site | (Toro et al. 2003) | MCUL |

| 15 | Pro192 | Leu | P192L | c.575A > G | 5 | Conserved | In core helice | (Chuang et al. 2005) | MCUL |

| 16 | Met195 | Thr | M195T | c.584 T > C | 5 | Conserved | In core helice | (Toro et al. 2003) | MCUL |

| 17 | His196 | Arg | H196R | c.587A > G | 5 | Conserved | In core helice | (Kiuru et al. 2002), (Lehtonen et al. 2004) | RCC, ULMS |

| 18 | Ile229 | Thr | I229T | c.686 T > C | 5 | Not conserved | Surface | (Alam et al. 2005b) | MCUL |

| 19 | Lys230 | Arg | K230R | c.689A > G | 5 | Conserved | Subunit stabilization | (Tomlinson et al. 2002), (Coughlin et al. 1998), (Manning et al. 2000) | FHD |

| 20 | Arg233 | Cys | R233C | c.697 C > T | 5 | Conserved | Active site | (Rustin et al. 1997), (Chuang et al. 2005), (Wei et al. 2006) | FHD, HLRCC, MCUL |

| 21 | Arg233 | His | R233H | c.698 G > A | 5 | Conserved | Active site | (Tomlinson et al. 2002), (Alam et al. 2005b), (Wei et al. 2006), (Chuang et al. 2005), (Toro et al. 2003) | HLRCC, MCUL |

| 22 | Arg233 | Leu | R233L | c.698 G > T | 5 | Conserved | Active site | (Chuang et al. 2005), (Toro et al. 2003) | MCUL |

| 23 | Ala239 | Thr | A239T | c.715 G > A | 5 | Conserved | Near active site | (Lehtonen et al. 2004) | UL |

| 24 | Ala274 | Thr | A274T | c.820 G > A | 6 | Not conserved | Active site | (Ylisaukko-oja et al. 2006) | OMC |

| 25 | Gly282 | Val | G282V | c.845 G > T | 6 | Conserved | Active site | (Tomlinson et al. 2002), (Alam et al. 2005b) | MCUL |

| 26 | Ala308 | Thr | A308T | c.922 G > A | 7 | Conserved | Surface | (Coughlin et al. 1998) | FHD |

| 27 | Asn310 | Tyr | N310Y | c.928A > T | 7 | Conserved | Surface | (Alam et al. 2005b) | MCUL |

| 28 | Phe312 | Cys | F312C | c.935 T > G | 7 | Conserved | Surface | (Coughlin et al. 1998) | FHD |

| 29 | His318 | Tyr | H318Y | c.952 C > T | 7 | Semi-conserved | In core helice | (Toro et al. 2003), (Martinez-Mir et al. 2003) | HLRCC |

| 30 | His318 | Leu | H318L | c.953A > T | 7 | Semi-conserved | In core helice | (Deschauer et al. 2006) | FHD |

| 31 | Val322 | Asp | V322D | c.964 T > A | 7 | Conserved | In core helice (interaction with 1 other monomer) | (Toro et al. 2003) | MCUL |

| 32 | Thr330 | Pro | T330P | c.988A > C | 7 | Semi-conserved | In core helice (interaction with 1 other monomer) | (Chuang et al. 2005) | MCUL |

| 33 | Cys333 | Tyr | C333Y | c.998 G > A | 7 | Semi-conserved | In core helice (interaction with 1 other monomer) | MCUL | |

| 34 | Ser334 | Arg | S334R | c.1002 T > G | 7 | Conserved | In core helice (interaction with 1 other monomer) | (Badeloe et al. 2006) | CL |

| 35 | Leu335 | Pro | L335P | c.1004 T > C | 7 | Conserved | In core helice | (Toro et al. 2003) | MCUL |

| 36 | Asn340 | Lys | N340K | c.1020 T > A | 7 | Semi-conserved | In core helice | (Toro et al. 2003), (Wei et al. 2006) | MCUL |

| 37 | Glu355 | Lys | E355K | c.1063 G > A | 7 | Conserved | Subunit stabilization | (Alam et al. 2005b) | MCUL |

| 38 | Asn361 | Lys | N361K | c.1083 T > A | 7 | Conserved | Active site | (Alam et al. 2005b) | HLRCC-CDC |

| 39 | Glu362 | Gln | E362Q | c.1084 G > C | 7 | Conserved | Active site | (Bourgeron et al. 1994) | FHD |

| 40 | Ser365 | Gly | S365G | c.1093 G > A | 7 | Conserved | Active site | (Toro et al. 2003), (Wei et al. 2006) | MCUL |

| 41 | Ser366 | Asn | S366N | c.1097 G > A | 7 | Conserved | Active site (but out) | (Toro et al. 2003), (Alam et al. 2005b) | MCUL |

| 42 | Met368 | Thr | M368T | c.1103 T > C | 7 | Conserved | Active site | (Badeloe et al. 2006) | MCUL |

| 43 | Pro369 | Ser | P369S | c.1105 C > T | 7 | Conserved | Active site (but out) | (Maradin et al. 2006) | FHD |

| 44 | Asn373 | Ser | N373S | c.1118A > G | 8 | Conserved | Active site | (Lehtonen et al. 2004) | HLRCC/clear cell RCC |

| 45 | Gln376 | Pro | Q376P | c.1127A > C | 8 | Conserved | In core helice (interaction with 1 other monomer) | (Zeman et al. 2000), (Remes et al. 2004), (Phillips et al. 2006) | FHD |

| 46 | Ala385 | Asp | A385D | c.1154 C > A | 8 | Not conserved | In core helice (interaction with 2 other monomers) | (Wei et al. 2006) | MCUL |

| 47 | Val394 | Leu | V394L | c.1180 G > C | 8 | Not conserved | In core helice | (Martinez-Mir et al. 2003) | MCUL |

| 48 | Gly397 | Arg | G397R | c.1189 G > A | 8 | Semi- conserved | In core helice | (Alam et al. 2005b) | MCUL |

| 49 | His402 | Cys | H402C | c.1207 C > T | 8 | Conserved | In core helice turn (interaction with 2 other monomers) | (Phillips et al. 2006) | FHD |

| 50 | Ser419 | Pro | S419P | c.1255 T > C | 9 | Conserved | In core helice | (Wei et al. 2006) | HLRCC |

| 51 | Asp425 | Val | D425V | c.1274A > T | 9 | Conserved | In core helice (interaction with 1 other monomer) | (Coughlin et al. 1998) | FHD |

| 52 | Gln439 | Pro | Q439P | c.1316A > C | 9 | Not conserved | Surface | (Wei et al. 2006) | HLRCC |

| 53 | Met454 | Ile | M454I | c.1362 G > A | 9 | Conserved | Subunit interaction | (Carvajal-Carmona et al. 2006) | LCT |

| 54 | Tyr465 | Cys | Y465C | c.1394A > G | 10 | Semi- conserved | Surface | (Toro et al. 2003) | MCUL |

| 55 | Leu507 | Pro | L507P | c.1520 T > C | 10 | Semi- conserved | Surface near opening active site | (Alam et al. 2005b) | MCUL |

Fig. 2.

Clustering of human fumarase missense mutations observed in FHD, MCUL1 and HLRCC. The active site is highlighted in cyan. Positions of amino acid mutations are indicated as small spheres and numbered according to Table 2. The positions around the active site are indicated in red, mutations affecting inter- or intrasubunit interactions are indicated in dark yellow. For clarity, one monomeric subunit is omitted

Acknowledgments

Help in data collection at SLS (Swiss Light Source, Villigen, CH) by Frank von Delft, Annette Roos and Panagis Filippakopoulos is gratefully acknowledged. The Structural Genomics Consortium is a registered charity (Number 1097737) funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomic institute, GlaxoSmithKline, Karolinska Institutet, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Innovation, Merck and Co., Inc., the Novartis Research Foundation, the Swedish Agency for Innovation Systems, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research and the Wellcome Trust. The study was supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Unit.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- FH

Fumarate hydratase

- FHD

Fumarate hydratase deficiency

- MCUL1

Multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomata

- HLRC

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer syndrome

Footnotes

References to electronic databases:

OMIM: 606812 150800, 605839, 136850; EC 4.2.1.2; Gene symbol: FH; GenBank: 19743875; URL to the interactive version of the article: http://www.ssiem.org/resources/structures/FH/; PDB code: 3E04

Competing interest: None declared.

References

- Alam NA, Olpin S, Leigh IM. Fumaratehydratase mutations and predisposition to cutaneous leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas and renal cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam NA, Olpin S, Rowan A, Kelsell D, Leigh IM, Tomlinson IP, Weaver T. Missense mutations in fumaratehydratase in multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:437–443. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60574-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badeloe S, van Geel M, van Steensel MA, Bastida J, Ferrando J, Steijlen PM, Frank J, Poblete-Gutierrez P. Diffuse and segmental variants of cutaneous leiomyomatosis: novel mutations in the fumaratehydratase gene and review of the literature. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:735–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley JP, Launonen V, Tomlinson IP. The FH mutation database: an online database of fumaratehydratase mutations involved in the MCUL (HLRCC) tumor syndrome and congenital fumarase deficiency. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeron T, Chretien D, Poggi-Bach J, Doonan S, Rabier D, Letouze P, Munnich A, Rotig A, Landrieu P, Rustin P. Mutation of the fumarase gene in two siblings with progressive encephalopathy and fumarase deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2514–2518. doi: 10.1172/JCI117261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal-Carmona LG, Alam NA, Pollard PJ, Jones AM, Barclay E, Wortham N, Pignatelli M, Freeman A, Pomplun S, Ellis I, Poulsom R, El-Bahrawy MA, Berney DM, Tomlinson IP. Adult leydig cell tumors of the testis caused by germlinefumaratehydratase mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3071–3075. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCP4 The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan I, Wong T, Martinez-Mir A, Christiano AM, McGrath JA. Familial multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas associated with papillary renal cell cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:75–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang GS, Martinez-Mir A, Geyer A, Engler DE, Glaser B, Cserhalmi-Friedman PB, Gordon D, Horev L, Lukash B, Herman E, Cid MP, Brenner S, Landau M, Sprecher E, Garcia Muret MP, Christiano AM, Zlotogorski A. Germlinefumaratehydratase mutations and evidence for a founder mutation underlying multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin EM, Christensen E, Kunz PL, Krishnamoorthy KS, Walker V, Dennis NR, Chalmers RA, Elpeleg ON, Whelan D, Pollitt RJ, Ramesh V, Mandell R, Shih VE. Molecular analysis and prenatal diagnosis of human fumarase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;63:254–262. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1998.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschauer M, Gizatullina Z, Schulze A, Pritsch M, Knoppel C, Knape M, Zierz S, Gellerich FN. Molecular and biochemical investigations in fumarase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;88:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinritz W, Paasch U, Sticherling M, Wittekind C, Simon JC, Froster UG, Renner R. Evidence for a founder effect of the germlinefumaratehydratase gene mutation R58P causing hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) Ann Hum Genet. 2008;72:35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan JF, Aleck KA, Tarby TJ, Bird CR, Heidenreich RA. Fumaric aciduria: clinical and imaging features. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:583–588. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200005)47:5<583::AID-ANA5>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A, Selak MA, Gottlieb E. Succinate dehydrogenase and fumaratehydratase: linking mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:4675–4682. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuru M, Lehtonen R, Arola J, Salovaara R, Jarvinen H, Aittomaki K, Sjoberg J, Visakorpi T, Knuutila S, Isola J, Delahunt B, Herva R, Launonen V, Karhu A, Aaltonen LA. Few FH mutations in sporadic counterparts of tumor types observed in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer families. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4554–4557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen R, Kiuru M, Vanharanta S, Sjoberg J, Aaltonen LM, Aittomaki K, Arola J, Butzow R, Eng C, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Isola J, Jarvinen H, Koivisto P, Mecklin JP, Peltomaki P, Salovaara R, Wasenius VM, Karhu A, Launonen V, Nupponen NN, Aaltonen LA. Biallelic inactivation of fumaratehydratase (FH) occurs in nonsyndromic uterine leiomyomas but is rare in other tumors. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:17–22. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63091-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning NJ, Olpin SE, Pollitt RJ, Downing M, Heeley AF, Young ID. Fumaratehydratase deficiency: increased fumaric acid in amniotic fluid of two affected pregnancies. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2000;23:757–759. doi: 10.1023/A:1005667906032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maradin M, Fumic K, Hansikova H, Tesarova M, Wenchich L, Dorner S, Sarnavka V, Zeman J, Baric I. Fumaricaciduria: mild phenotype in a 8-year-old girl with novel mutations. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:683. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0321-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Mir A, Glaser B, Chuang GS, Horev L, Waldman A, Engler DE, Gordon D, Spelman LJ, Hatzibougias I, Green J, Christiano AM, Zlotogorski A. Germlinefumaratehydratase mutations in families with multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomata. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:741–744. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TM, Gibson JB, Ellison DA. Fumaratehydratase deficiency in monozygotic twins. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35:150–153. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard PJ, Briere JJ, Alam NA, Barwell J, Barclay E, Wortham NC, Hunt T, Mitchell M, Olpin S, Moat SJ, Hargreaves IP, Heales SJ, Chung YL, Griffiths JR, Dalgleish A, McGrath JA, Gleeson MJ, Hodgson SV, Poulsom R, Rustin P, Tomlinson IP. Accumulation of Krebs cycle intermediates and over-expression of HIF1alpha in tumours which result from germline FH and SDH mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2231–2239. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe PJ. Fumaratehydratase deficiency and cancer: activation of hypoxia signaling? Cancer Cell. 2007;11:303–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remes AM, Filppula SA, Rantala H, Leisti J, Ruokonen A, Sharma S, Juffer AH, Hiltunen JK. A novel mutation of the fumarase gene in a family with autosomal recessive fumarase deficiency. J Mol Med. 2004;82:550–554. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0563-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose IA, Weaver TM. The role of the allosteric B site in the fumarase reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3393–3397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307524101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustin P, Bourgeron T, Parfait B, Chretien D, Munnich A, Rotig A. Inborn errors of the Krebs cycle: a group of unusual mitochondrial diseases in human. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1361:185–197. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(97)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson IP, Alam NA, Rowan AJ, Barclay E, Jaeger EE, Kelsell D, Leigh I, Gorman P, Lamlum H, Rahman S, Roylance RR, Olpin S, Bevan S, Barker K, Hearle N, Houlston RS, Kiuru M, Lehtonen R, Karhu A, Vilkki S, Laiho P, Eklund C, Vierimaa O, Aittomaki K, Hietala M, Sistonen P, Paetau A, Salovaara R, Herva R, Launonen V, Aaltonen LA. Germline mutations in FH predispose to dominantly inherited uterine fibroids, skin leiomyomata and papillary renal cell cancer. Nat Genet. 2002;30:406–410. doi: 10.1038/ng849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, Warren MB, Glenn GM, Turner ML, Stewart L, Duray P, Tourre O, Sharma N, Choyke P, Stratton P, Merino M, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Schmidt LS, Zbar B. Mutations in the fumaratehydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:95–106. doi: 10.1086/376435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei MH, Toure O, Glenn GM, Pithukpakorn M, Neckers L, Stolle C, Choyke P, Grubb R, Middelton L, Turner ML, Walther MM, Merino MJ, Zbar B, Linehan WM, Toro JR. Novel mutations in FH and expansion of the spectrum of phenotypes expressed in families with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. J Med Genet. 2006;43:18–27. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylisaukko-oja SK, Cybulski C, Lehtonen R, Kiuru M, Matyjasik J, Szymanska A, Szymanska-Pasternak J, Dyrskjot L, Butzow R, Orntoft TF, Launonen V, Lubinski J, Aaltonen LA. Germlinefumaratehydratase mutations in patients with ovarian mucinous cystadenoma. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:880–883. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Krijt J, Stratilova L, Hansikova H, Wenchich L, Kmoch S, Chrastina P, Houstek J. Abnormalities in succinylpurines in fumarase deficiency: possible role in pathogenesis of CNS impairment. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2000;23:371–374. doi: 10.1023/A:1005639516342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng WQ, Gao H, Brueton L, Hutchin T, Gray G, Chakrapani A, Olpin S, Shih VE. Fumarase deficiency caused by homozygous P131R mutation and paternal partial isodisomy of chromosome 1. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1004–1009. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]