Abstract

Objective: To examine the relation between different types of alcoholic drinks and upper digestive tract cancers (oropharyngeal and oesophageal).

Design: Population based study with baseline assessment of intake of beer, wine, and spirits, smoking habits, educational level, and 2-19 years’ follow up on risk of upper digestive tract cancer.

Setting: Denmark.

Subjects: 15 117 men and 13 063 women aged 20 to 98 years.

Main outcome measure: Number and time of identification of incident upper digestive tract cancer during follow up.

Results: During a mean follow up of 13.5 years, 156 subjects developed upper digestive tract cancer. Compared with non-drinkers (drinkers of <1 drink/week), subjects who drank 7-21 beers or spirits a week but no wine were at a risk of 3.0 (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 6.1), whereas those who had the same total alcohol intake but with wine as ⩾30% of their intake had a risk of 0.5 (0.2 to 1.4). Drinkers of >21 beers and spirits but no wine had a relative risk of 5.2 (2.7 to 10.2) compared with non-drinkers, whereas those who drank the same amount, but included wine in their alcohol intake, had a relative risk of 1.7 (0.6 to 4.4).

Conclusion: A moderate intake of wine probably does not increase the risk of upper digestive tract cancer, whereas a moderate intake of beer or spirits increases the risk considerably.

Key messages

Alcohol is a strong risk factor for oropharyngeal and oesophageal cancer

The carcinogenic effect of alcohol has been assumed to be independent of type of alcohol drunk

Resveratrol, a substance in grapes and wine, has been shown to inhibit the initiation, promotion, and progression of cancer

Wine drinkers may be at a lower risk of developing upper digestive tract cancer than drinkers who have a similar intake of beer or spirits

Introduction

Several epidemiological studies have found a strong association between alcohol intake and the cancers of the upper digestive tract: oropharyngeal and oesophageal cancers.1–3 We have shown that mortality from all causes depends on the type of alcohol ingested. The decreased mortality among wine drinkers was attributable to cardiovascular as well as to non-cardiovascular deaths.4 In Denmark, as in other Western countries, cancer is the most common non-cardiovascular cause of death.

The increased risk of cancers of the oropharynx and the oesophagus is attributed to the exposure of the surfaces of these organs to high concentrations of alcohol.5 Wine contains several components with possible anticarcinogenic effect—these may exert their action locally in parallel with the possible effect of ethanol.6 One of these compounds, resveratrol, has recently been shown in an experimental study to inhibit the initiation, promotion, and progression of tumours.7

We examined the effect of intake of beer, wine, and spirits on the incidence of upper digestive tract cancers in a population based series of prospective cohort studies.

Methods

Population

The Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Population Studies coordinates three comprehensive Danish programmes of prospective population studies: the Copenhagen city heart study, the Copenhagen male study, and the Copenhagen county centre of preventive medicine (formerly, the Glostrup population studies)—the latter including the MONICA project (an international study conducted under the auspices of the World Health Organisation to monitor trends in, and determinants of, mortality from cardiovascular disease). The Copenhagen city heart study and the Glostrup population studies were age stratified and randomly selected from defined areas in greater Copenhagen, and the subjects in the Copenhagen male study were from 14 large workplaces in Copenhagen. Mean participation rate was 80% (69-88%). All population studies included a health examination and a self administered questionnaire on various health related issues, including alcohol intake, smoking habits, and school education. The answers to the questionnaires were checked by the staff during the examination. Detailed descriptions of the studies have been published previously.8–10

Questionnaire

Subjects in the Copenhagen male study were asked about an average daily intake of beer, wine, and spirits on weekdays (Monday to Thursday) and at weekends (Friday to Sunday). Daily intakes were summed to give a weekly intake. Participants in the Glostrup population studies and the Copenhagen city heart study gave details of their average weekly intake of each type of alcoholic drink. One beer contains 12 g of alcohol, which can be considered to be the amount of alcohol in a standard alcoholic drink in Denmark. The subjects reported whether they were “never smokers,” former smokers, or current smokers. For the analysis, five groups were defined: never smokers; former smokers with >5 years’ smoking; former smokers with ⩽5 years’ smoking; smokers of 1-19 g tobacco/day; and smokers of ⩾20 g tobacco/day.

Follow up

Patients with cancer were identified by record linkage between the present populations and the cancer register at the Danish cancer registry.11 Vital status of the population sample was followed until 1 January 1994, by using the unique person identification number in the national, central person register. The observation time for each participant was the period from the date of the initial examination until 1 January 1994, until the date that upper digestive tract cancer was diagnosed, or until the date of death, emigration, or disappearance. The cancer was defined according to the 7th revision of the international classification of diseases as 140.0 to 149.0 (oral cavity and pharyngeal cancers) and 150.0 (oesophageal cancers).

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed by means of Cox regression models, with age as the time scale.12 A first series of models included sex and total alcohol intake (6 categories), and first order interactions between these variables. Smoking habits (5 levels) and educational level (3 levels) were added to this model. We constructed a second series of models including the same covariates as above but using intake of beer, wine, and spirits instead of alcohol intake. Introduction of a first order interaction term between beer and spirits, beer and wine, and spirits and wine implied no significant improvement of the fit of the model to the data. We thus concluded that there was no evidence of interaction between the three types of drinks on the risk of developing upper digestive tract cancer.

Subjects were stratified according to total alcohol intake per week: (a) <1 drink (non-drinkers), (b) 1-6 drinks, (c) 7-21 drinks, and (d) >21 drinks. Relative risks of upper digestive tract cancer according to percentage of wine in the total alcohol intake (no wine, 1-30% wine, or >30% wine) was estimated for these groups, including the same covariates as above. To avoid bias because of presence of upper digestive tract cancer at the time of measuring exposure, the above mentioned models were repeated after exclusion of the first two years of the follow up period. This resulted in no changes in the reported estimates.

Results

During a total of 347 425 person years we found 4987 cases of first identification of cancer; in 156 of these subjects (follow up 2-19 (mean 13.5) years) the cancer was located in the upper digestive tract (90 oropharyngeal and 66 oesophageal).

Alcohol intake and upper digestive tract cancer

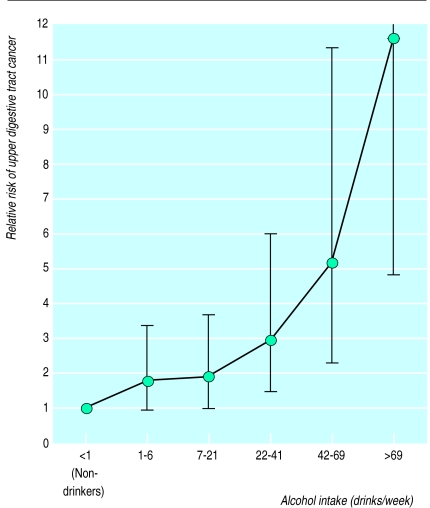

There was a strong dose-dependent increase in risk of upper digestive tract cancer with increased alcohol intake, when age, sex, smoking habits, and educational level were controlled for (fig 1). Compared with non-drinkers the risk of upper digestive tract cancer doubled among those drinking 7-21 drinks a week, whereas drinkers whose intake exceeded 69 drinks a week had a relative risk of 11.7 (95% confidence interval 4.9 to 27.8). Compared with non-smokers, smokers of 1-19 g tobacco/day had a relative risk of 5.0 (2.3 to 10.7) and smokers of ⩾20 g tobacco/day had a risk of 7.5 (3.4 to 16.9). No interaction was found between smoking and alcohol intake, but the number of cases of upper digestive tract cancer among non-smokers was quite low. Educational level was not associated with risk of upper digestive tract cancer (the relative risk was 1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) in the highest level compared with the lowest).

Figure 1.

Relative risk of upper digestive tract cancer for differing amounts of alcohol drunk. Vertical lines show 95% confidence limits after adjustment for age, sex, smoking habits and educational level (upper limit for >69 drinks a week is 27.9)

Beer, wine, and spirits, and upper digestive tract cancer

In a model including all three alcoholic drinks, intake of wine tended to reduce the risk of upper digestive tract cancer, whereas intake of beer and spirits significantly increased the risk (table 1). However, such a model has some disadvantages, even if the relation between one type of drink and upper digestive tract cancer is adjusted for intake of other types of drinks. The reference group comprises non-drinkers of one drink, but they may not be non-drinkers of the other drinks. Furthermore, mean total alcohol intake in the upper category (⩾7 drinks a week) differs with type of alcohol—for example, beer drinkers had a higher level of intake than spirits and wine drinkers. We therefore conducted an analysis of the effect of proportion of type of alcohol drunk, taking the total alcohol intake into account.

Table 1.

Relative risk (95% confidence interval) of upper digestive tract cancer, according to intake of beer, wine, and spirits, adjusted for age, sex, smoking habits, and educational level

| No of drinks/week | Beer | Wine | Spirits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1-6 | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.1) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.1) |

| ⩾7 | 2.9 (1.8 to 4.8) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.8) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) |

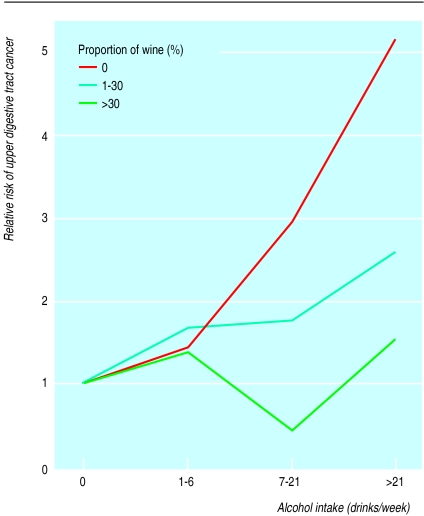

Subjects were categorised according to both the percentage of wine in their total alcohol intake and their total alcohol intake (table 2). The relative risk for these categories of drinking is shown in figure 2. The subjects who drank ⩾7 drinks a week and had a high relative intake of wine had a significantly lower risk. Among subjects drinking 7-21 drinks a week, those who drank only beer and spirits had a relative risk of 3.0 (1.5 to 6.1), whereas those who included >30% wine in their alcohol intake had a relative risk of 0.5 (0.2 to 1.4). Among subjects drinking >21 drinks a week, those who drank only beer and spirits had a relative risk of 5.2 (2.7 to 10.2), whereas those whose total alcohol intake comprised >30% wine had a relative risk of 1.7 (0.6 to 4.4). In concordance with this, a high proportion of beer or spirits of the total alcohol intake implied a higher risk of upper digestive tract cancer than did a low proportion (table 3).

Table 2.

Number of subjects (number of cases of oropharyngeal cancer; oesophageal cancer) and mean (SD) alcohol intake, according to total alcohol intake and percentage of wine in total intake

| Drinks per week |

% of wine in total alcohol intake

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0

|

1-30

|

>30

|

||||||

| No of subjects (no of cases) | Mean alcohol intake | No of subjects (no of cases) | Mean alcohol intake | No of subjects (no of cases) | Mean alcohol intake | |||

| 0 | 5468 (9;6) | 0 | ||||||

| 1-6 | 1527 (4;1) | 3.2 (1.7) | 1965 (7;6) | 3.8 (1.9) | 6062 (10;9) | 3.3 (1.6) | ||

| 7-21 | 1770 (10;9) | 12.0 (3.7) | 3148 (10;10) | 11.8 (3.6) | 3898 (6;0) | 12.5 (3.5) | ||

| >21 | 1498 (21;14) | 39.0 (22.6) | 1709 (8;9) | 36.8 (18.0) | 1135 (5;2) | 38.6 (15.0) | ||

Figure 2.

Relative risk for upper digestive tract cancer, according to proportion of wine in total alcohol intake and according to total alcohol intake. Relative risk is set at 1.0 among non-drinkers after adjustment for age, sex, smoking habits, and educational level

Table 3.

Relative risk of upper digestive tract cancer (95% confidence interval), according to total alcohol intake and percentage of beer and spirits in total intake

| % of total alcohol intake |

Alcohol intake (drinks/week)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-6 | 7-21 | >21 | |

| Beer: | |||

| 0 | 1.7 (0.8 to 3.5) | 1.2 (0.4 to 3.6) | 1.9 (0.2 to 14) |

| 1-30 | 1.9 (0.9 to 4.0) | 1.7 (0.5 to 6.0) | 3.0 (1.0 to 8.7) |

| >30 | 2.0 (0.6 to 6.2) | 2.1 (1.1 to 4.2) | 4.3 (2.2 to 8.4) |

| Spirits: | |||

| 0 | 1.5 (0.9 to 3.1) | 4.4 (1.6 to 12) | 3.0 (1.3 to 7.2) |

| 1-30 | 1.8 (0.7 to 4.7) | 2.8 (1.2 to 6.8) | 7.1 (2.8 to 18) |

| >30 | 2.5 (1.0 to 6.2) | 2.9 (0.8 to 7.5) | 10 (4.4 to 25) |

Reference group=non-drinkers (relative risk 1.0)

Discussion

These data confirm the well known association between total alcohol intake and risk of cancers of the upper digestive tract.1,3,13–15 Furthermore, the data show that the carcinogenic effect of alcohol may be restricted to beer and spirits and may not be present in wine.

Other studies

The association between type of alcoholic drink and upper digestive tract cancer has been addressed in several retrospective case-control studies with different results. A common feature of these studies was that the main type of alcohol drunk was also the type most strongly associated with risk of upper digestive tract cancer.16 This could be interpreted as all three types of drinks (beer, wine, and spirits) having an equally detrimental effect. Alternatively, this could be interpreted as a poor assessment of the intake of two of the three types of drinks, without proper adjustment for one type of alcoholic drink when estimating the effect of another. Moreover, in several studies there were few or no consumers of one or more of the different types of drinks.17 The findings of increased risk of upper digestive tract cancer with alcohol intake in countries predominantly drinking wine seems at first contradictory to our findings. On the other hand, beer and spirits are also drunk in these countries, thereby contributing to the increased odds ratios. Furthermore, the odds ratios for heavy drinkers versus non-drinkers found in these studies were only doubled, whereas risk of the same type of cancer from smoking was considerably higher.18 In our study, alcohol was a much stronger risk factor for upper digestive tract cancer than smoking, with a 12-fold increased risk among heavy drinkers compared with non-drinkers.

The conflicting results in the case-control studies may be the result of other methodological shortcomings, such as recall bias, insufficient adjustment for confounders,19 and selection bias.16 In case-control studies the information on alcohol is obtained from patients weeks, months, or years after the cancer is diagnosed or by interviewing the relatives after the patient’s death. The problem of recall bias of the alcohol intake is further reinforced by the long latency period between carcinogenesis and diagnosis. The present population study is based on prospective studies and so is not burdened by recall bias; the validity of the reported intake of beer, wine, and spirits seems high.20 Furthermore, the sensitivity of the questionnaire based information on average weekly alcohol intake is emphasised by the very high relative risk among heavy drinkers compared with non-drinkers (fig 1).

Confounders

Consumers of different alcoholic drinks may differ in other aspects of their lifestyle and thereby be at different risk of developing cancer. Heavy drinkers, for example, were more likely to be heavy smokers, and heavy smokers experienced a higher risk of upper digestive tract cancer than non-smokers (7.1 (95% confidence interval 3.2 to 15.0)). Thus in this study, smoking was a confounder that was carefully controlled for in all our analyses. Moreover, there was no interaction between effects of smoking and effects of total alcohol intake or type of alcohol drunk on risk of upper digestive tract cancer. Diet has been shown to be a risk factor for oesophageal cancer,21 but we have no data on dietary habits in the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Population Studies. On the other hand, dietary factors such as a high consumption of fruit and vegetables would have to be strongly associated with wine intake and with upper digestive tract cancer in the present population to be an effective confounder. To our knowledge, no clear relation between dietary factors and these variables has yet been found.

Anticarcinogenic properties of wine

Our findings on the relation between wine and upper digestive tract cancer are strongly supported by the recent experimental studies showing that resveratrol, one of several anticarcinogenic compounds in wine, inhibits the initiation, promotion, and progression of tumours.7,22

Acknowledgments

We thank M von Holstein, B Bredesen, and the staff of the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Studies for help; Adam Gottschau and Anders Munch Bjerg for statistical advice and data management; and the Copenhagen Centre for Prospective Population Studies—comprising the Copenhagen city heart study, the Copenhagen male study, and the Copenhagen county centre of preventive medicine (formerly, the Glostrup population studies)—for collecting all the original data.

Editorial by Sabroe

Footnotes

Funding: The study is supported by grants from the Danish National Board of Health and the Danish Medical Research Council. The Danish National Research Foundation established the Danish Epidemiology Science Centre.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Boffetta P, Garfinkel L. Alcohol drinking and mortality among men enrolled in an American cancer society prospective study. Epidemiology. 1990;1:342–348. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199009000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao Y-T, McLaughlin JK, Blot WJ, Ji BT, Benichou J, Dai Q, et al. Risk factors for esophageal cancer in Shanghai, China. 1. Role of cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:192–196. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato I, Nomura AMY, Stemmermann GN, Chyou P-H. Prospective study of the association of alcohol with cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract and other sites. Cancer Causes Control. 1992;3:145–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00051654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grønbæk M, Deis A, Sørensen TIA, Becker U, Schnohr P, Jensen G. Mortality associated with moderate intake of wine, beer, or spirits. BMJ. 1995;310:1165–1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6988.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieber CS. Medical and nutritional complications of alcoholism. New York: Plenum Medical; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winn DM. Diet and nutrition in the etiology of oral cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:S437–S445. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.2.437S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CW, et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science. 1997;275:218–220. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appleyard M, Hansen AT, Schnohr P, Jensen G, Nyboe J. The Copenhagen City Heart Study. A book of tables with data from the first examination (1976-78) and a five year follow-up (1981-83) Scand J Soc Med. 1989;170:1–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hein HO, Sørensen H, Suadicani P, Gyntelberg F. Alcohol consumption, Lewis phenotypes, and risk of ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1993;341:392–396. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92987-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heitmann B. The influence of fatness, weight change, slimming history and other lifestyle variables on diet reporting in Danish men and women aged 35-65 years. Int J Obesity. 1993;17:329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storm HH, Sprøgel P, Bang S, Møller Jensen O. Cancer incidence in Denmark 1986. Copenhagen: Danish Cancer Society; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen PK, Borgan Ø, Gill RD, Keiding N. Statistical models based on counting processes. New York: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macfarlane GJ, Macfarlane TV, Lowenfels AB. The influence of alcohol consumption on worldwide trends in mortality from upper aerodigestive tract cancers in men. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996;50:636–639. doi: 10.1136/jech.50.6.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen J, Sabroe S, Ipsen J. Effect of combined alcohol and tobacco exposure on risk of cancer of the hypopharynx. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1985;39:304–307. doi: 10.1136/jech.39.4.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merletti F, Boffetta P, Ciccone G, Mashberg A, Terracini B. Role of tobacco and alcoholic beverages in the etiology of cancer of the oral cavity/oropharynx in Torino, Italy. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4919–4924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabat GC, Wynder EL. Type of alcoholic beverage and oral cancer. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:190–194. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Winn DM, Austin DF, Greenberg RS, Pecston-Martin S, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3282–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tavani A, Negri E, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Risk factors for esophageal cancer in women in northern Italy. Cancer. 1993;72:2531–2536. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931101)72:9<2531::aid-cncr2820720903>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuyns AJ, Péquignot G, Abbatucci JS. Oesophageal cancer and alcohol consumption; importance of type of beverage. Int J Cancer. 1979;23:443–447. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910230402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grønbæk M, Heitmann B. Validity of self-reported intakes of wine, beer and spirits in population studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50:487–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decarli A, Liati P, Negri E, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Vitamin A and other dietary factors in the etiology of esophageal cancer. Nutr Cancer. 1987;10:29–37. doi: 10.1080/01635588709513938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uenobe F, Nakamura S, Miyazawa M. Antimutagenic effect of resveratrol against Trp-P-1. Mutat Res. 1997;373:197–200. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(96)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]