Abstract

Language and literacy skills established during early childhood are critical for later school success. Parental engagement with children has been linked to a number of adaptive characteristics in preschoolers including language and literacy development, and family-school collaboration is an important contributor to school readiness. This study reports the results of a randomized trial of a parent engagement intervention designed to facilitate school readiness among disadvantaged preschool children, with a particular focus on language and literacy development. Participants included 217 children, 211 parents, and 29 Head Start teachers in 21 schools. Statistically significant differences in favor of the treatment group were observed between treatment and control participants in the rate of change over 2 academic years on teacher reports of children’s language use (d = 1.11), reading (d = 1.25), and writing skills (d = .93). Significant intervention effects on children’s direct measures of expressive language were identified for a subgroup of cases where there were concerns about a child’s development upon entry into preschool. Additionally, other child and family moderators revealed specific variables that influenced the treatment’s effects.

Language is one of the most powerful symbolic systems through which children learn to understand and interpret their physical, social, and conceptual worlds (Harwood, Miller, & Irizarry, 1995; Owen, 2008). Language skills are important precursors for all aspects of development because of their close links to conceptual and social development (Samuelson & Smith, 2005) and to literacy skills and school success (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 2001). Children who begin school without essential language skills are significantly more likely to require remedial education and to drop out of school than their peers who begin school with a solid grasp of essential language skills (Dickinson & Tabors, 2001).

Unfortunately, there are many underserved and at-risk children who enter school with delayed language abilities. Children living in low income families are particularly vulnerable (Bornstein & Bradley, 2003; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000); they are at significant risk for dire developmental outcomes, including school failure, learning disabilities, behavior problems, developmental delay, and health impairments (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Wood, 2003). Their social interactions are often limited in linguistic complexity and quantity in ways that are highly predictive of poorer outcomes, compared to middle-class children (Hart & Risley, 1995). Other factors that make children linguistically vulnerable, and are often collinear with low-income status, include low levels of parental education (Raviv, Kessenich, & Morrison, 2004; Roberts, Bornstein, Slater, & Barrett, 1999), parental health problems (Essex, Klein, Miech, & Smider, 2001), and having a first language other than English, especially when compounded by low SES (Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005; National Task Force on Early Childhood Education for Hispanics, 2007). For young children with disabilities or developmental concerns, a lack of foundational experiences in early language and literacy has lasting deleterious effects on literacy skills (Catts, Fey, Tomblin, & Zhang, 2002). Even when low-income and linguistically-vulnerable children receive interventions that improve their academic performance over similar peers who do not receive specialized intervention, their performance on average still lags behind their middle-income peers (Administration for Children & Families, 2005). For these children, gaps between themselves and their more advantaged peers exist upon school entry and widen as they move through the educational experience.

Given the essential predictive nature of language and early literacy skills (e.g., attending to stories, alphabet knowledge, and print awareness) at school entry, it is imperative that effective interventions be identified to support language and literacy development in early childhood environments (Administration for Children & Families, 2005; Justice, Mashburn, Hamre, & Pianta, 2008; Landry, 2002; Whitehurst et al., 1994). The two most important developmental systems to influence young children are families and schools. Family is the primary system, and because it is generally a lifelong resource, it is the most important. Very few educational interventions have produced results with such consistently positive, significant, and stable effects over time, geographic context, developmental level, and subject areas as parent support and participation (Jeynes, 2003, 2005; Nye, Turner, & Schwartz, 2006).

A great deal of early language and social learning occurs in the context of interactive experiences within children’s families when parents are highly engaged, and where “parents” are defined as those significant individuals most involved with and responsible for children (Bowman, Donovan, & Burns, 2001). We conceptualize parent engagement as behaviors that connect with and support children or others in their environment in ways that are interactive, purposeful, and directed toward meaningful learning and affective outcomes. Parent engagement includes interactions and provision of experiences that nurture children and promote children’s autonomy and learning. Thus, we view parent engagement as a more general concept than traditional parent involvement, which is often more narrowly understood as school- or home-based activities that are supportive of school efforts and children’s performance in school. In this paper, we consider parent engagement as composed of three dimensions: (a) warmth, sensitivity, and responsiveness; (b) support for a child’s emerging autonomy and self-control; and (c) participation in learning and literacy. Hindman and Morrison (2010) and Morrison (2009) found support for such a three-dimensional model of parenting. Responding with affective warmth to a child’s cues, providing structure through control and discipline, and establishing home support for learning related significantly to children’s social and academic success in their studies. This evidence for a three-dimensional relational model provides support of our approach to parent engagement.

Parental warmth, sensitivity, and responsiveness, and support for a child’s autonomy and emerging self-control are highly predictive of children’s socioemotional and cognitive development (Chazan-Cohen et al., 2009; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2002; Roggman, Boyce, & Cook, 2009). Children whose parents interact with them using sensitive, responsive behaviors have been found to demonstrate social, emotional, communicative, and cognitive competence (Landry, Swank, Smith, Assel, & Gunnewig, 2006; Merlo, Bowman, & Barnett, 2007). Parental behaviors that support a child’s autonomy and curiosity also enhance development in positive ways in that social assertiveness, self-directedness, cognition, and communication with peers are enhanced when parents provide developmentally-sensitive support for their autonomous problem solving (Grolnik, Gurland, DeCourcey, & Jacob, 2002; Pomerantz, Moorman, & Litwack, 2007). Active and meaningful parental participation in language- and literacy-related activities have been reported as important in facilitating optimal school readiness and success (El Nokali, Bachman, & Votruba-Drzal, 2010; Espinosa, 2002; Pan, Rowe, Singer, & Snow, 2005; Wood, 2002). Parental efforts to enhance the learning and literacy environment at home through rich verbal exposure, joint book reading, and provision of print materials are positively related to preschool children’s emergent literacy skills (Sénéchal, 2006; Weigel, Martin, & Bennett, 2006).

School (including early childhood educational settings, such as Head Start and high-quality child care) is the second predominant developmental system, and it can establish a context for programs that attempt to provide equal access to educational opportunities for all children and their families. Our belief in both families and schools as the foundation for meaningful change is grounded in ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, l979). Ecological systems theory considers child development within the context of interacting systems (including the child, peers, adults, learning environments, community agencies, and policies) that influence and are influenced by one another (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Hobbs, l966). Specific to this study, the relationships that occur within primary settings (e.g., the microsystems of home and school), and relationships between primary systems and settings (i.e., the interface between family and school systems, or the mesosystem) influence child development and learning in significant ways.

Consistent with ecological systems theory, the educational experience for underserved learners can be bolstered through means that create connections among primary socializing systems, through the establishment and maintenance of family–school partnerships. In a cross-systems (i.e., family–school) partnership approach, families and school professionals cooperate, coordinate, and collaborate to enhance opportunities and success for children and adolescents in the social, emotional, behavioral, and academic domains (Christenson & Sheridan, 2001). Family–school partnership models focus on creating a constructive relationship to promote positive social–emotional, behavioral, and academic and developmental trajectories in children and youth, emphasizing the reciprocal influence and shared responsibility for educating and socializing children (Christenson & Sheridan, 2001). In partnership models, emphasis is placed on the co-construction of goals and priorities for children’s learning, mutual contributions around information-sharing and decision-making, sharing in the responsibility for child progress, and joint monitoring of goal attainment (Fantuzzo, Tighe, & Childs, 2000; Sheridan & Kratochwill, 2008). Such partnerships may be particularly important during the early childhood years (Raffaele & Knoff, 1999) when parents are developing a role construct (i.e., concepts and plans) for how they may or may not become an active participant in their children’s learning and development.

Despite consistent findings linking positive relationships and family–school partnerships to desirable developmental outcomes, research-based interventions that focus on partnering with families to determine goals, priorities, and culturally relevant practices in early childhood are sparse (Hoagwood, 2005). The Getting Ready intervention (Sheridan, Knoche, Edwards, Bovaird, & Kupzyk, 2010; Sheridan, Marvin, Knoche, & Edwards, 2008) was designed to provide an integrated, ecological approach to promoting children’s competency to function in school, that is, their school readiness within existing early childhood programs. It is responsive to calls encouraging “true partnership” models between families and professionals (Huang et al., 2005) through a research-based, family-centered collaborative structure. It represents a general model for professionals’ interactions with parents, as well as a structured process for delivering individualized services, as opposed to a packaged intervention delivered in a prescriptive manner with predetermined sessions and scripts. That is, the specific content emphasized for each child and family is individualized, and is not predetermined by intervention protocols. In the Getting Ready approach, professionals provide early intervention and education services for parents and children that focus on child development and learning outcomes by (a) guiding parents to engage in warm and responsive interactions, to support their children’s autonomy, and to participate in children’s learning and (b) supporting parents and teachers in collaborative partnership-based interactions to facilitate mutual responsibility for children’s targeted learning and development.

The Getting Ready intervention integrates two research-supported interventions (i.e., triadic consultation, McCollum & Yates, 1994, and collaborative/conjoint consultation, Sheridan & Kratochwill, 1992, 2008) in a unique, ecologically- and strengths-based relational approach (Sheridan et al., 2008). The precursors to Getting Ready—triadic and collaborative (conjoint) consultation—focus individually on essential parent–child and parent–teacher relationships, respectively. Triadic consultation is an intervention validated with infants and young children with developmental delays and disabilities. Its aim is to strengthen parental warmth and sensitivity as well as parental competence in supporting autonomy and learning, all within the context of everyday parent–child interactions (Girolametto, Verbey, & Tannock, 1994; Mahoney & MacDonald, 2007; McCollum, Gooler, Appl, & Yates, 2001). Collaborative (conjoint) consultation provides a guiding structure by which adults (i.e., parents, professionals, and consultants) join together to collectively support a child’s social, cognitive, linguistic, and behavioral development. It provides a process for linking systems of home and school to promote joint attention to a child’s needs, mutual goal setting, shared responsibility and decision making, and consistent approaches to support children’s unique learning needs.

Research on the Getting Ready intervention implementation found that relative to a control group of preschoolers receiving typical Head Start services, those participating in the treatment group showed significantly greater positive direct effects in the area of teacher-reported social-emotional functioning over time. Specifically, teachers reported increased attachment behaviors with adults (p < .01; d = 0.75) improved initiative (p < .05; d = 0.56); and reduced anxiety/withdrawal behaviors (p < .01; d = −0.74; Sheridan et al., 2010). Furthermore, teachers participating in the Getting Ready intervention have been found to interact with parents in ways intended to support and enhance parent child interactions around learning activities (Knoche, Sheridan, Edwards, & Osborn, 2010). Relative to control teachers, those in the Getting Ready treatment group demonstrated significantly greater effectiveness at initiating parental interest and engagement during home visits (p < .05; d = 0.61). They were observed significantly more often using strategies promoting parent–child interaction and parent teacher collaboration (p < .05; d = 0.53), establishing a parent–child relationship (p < .05; d = 0.58), brainstorming with parents (p < .05; d = 0.55), and affirming parents’ competence (p < .001; d = 0.97). Parents and children in the Getting Ready treatment group were observed to spend significantly more time interacting and engaging with one another during home visits (p < .01; d = 0.69; Knoche et al., 2010) than parents and children in the control group. In-depth reviews of home visit records and classroom newsletters provided strong evidence of treatment teachers’ generalization of collaborative planning and problem-solving with parents, relative to control teachers, with clear evidence of their efforts to strengthen home-school collaboration and form relationships with parents (Edwards, Hart, Rasmussen, Haw, & Sheridan, 2009). The most striking finding from home visit reports was the difference favoring the teachers in the Getting Ready treatment group in amount, depth, and detail of child-oriented goal-setting with families.

In many developmental studies, both family and child variables have been found to be responsible for influencing the effectiveness of an intervention. Low parental education, particularly the lack of a high school or equivalent degree, repeatedly has been found to be a risk factor in children’s language development (Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Pianta, & Howes, 2002), and children who live in households with just one adult are at greatest risk of displaying delays in overall development (National Council of Welfare, 2004). Parental mental and physical health status also has been considered a risk factor in longitudinal studies of children’s development (Sameroff, Seifer, Zax, & Barocas, 1987; Whitaker, Orzol, & Kahn, 2006), with maternal general health positively associated with positive scores on a brief measure of parenting (Waylen & Stewart-Brown, 2009). In addition to these designated familial characteristics, certain child characteristics are also likely to contribute to intervention effectiveness. Speaking a primary language other than English during the preschool years may put a child at risk for delays in English language and literacy development (Rinaldi & Paez, 2008). Concerns regarding early development as expressed by parents or teachers are often associated with delays in language and literacy later in life (Hammer, Farkas, & Maczuga, 2010). These family and child variables are considered important in potentially moderating the effects of the Getting Ready intervention on children’s language and literacy skills.

Purpose of Study

The purpose of the present study is to test the efficacy of the Getting Ready intervention on children’s readiness skills related to early language and literacy as assessed directly and via teacher report. Past research has already established the contribution of the Getting Ready intervention on social-emotional outcomes in young children above and beyond those found in Head Start programs (Sheridan et al., 2010). Our primary research question concerned whether the Getting Ready intervention is efficacious in supporting the language and literacy development of preschool children in Head Start settings, relative to children receiving Head Start without the additional parent engagement intervention. Two independent but complementary sources of information were collected by directly assessing the children’s expressive language skills in the Head Start setting and by seeking an independent rating of the children’s classroom language and literacy behaviors from the teachers who observed the children on a daily basis.

Two primary research questions were posed: (1) What is the effect of the Getting Ready intervention on children’s language and literacy behaviors? We hypothesized that children in the Getting Ready condition would demonstrate greater gains over time on both teacher-reported and direct assessments of language and literacy relative to the control group. (2) Do certain family variables (i.e., parental education, parental health, and number of adults in the home) or child variables (i.e., entering preschool not speaking English, per parental report, or presence of a developmental concern, per parent or teacher report) moderate the effects of the Getting Ready intervention on children’s language and literacy outcomes? We expected that certain family and child characteristics may influence the manner in which children responded to the Getting Ready intervention, such that family risk factors (e.g., education and health) and child risk factors (e.g., language and developmental concerns) would result in lower language and literacy outcomes. We expected that more adults in the home would amplify the effects of the intervention.

Method

Setting and Context

This study was one of eight conducted as part of the Interagency School Readiness Consortium1 to identify efficacious interventions promoting school readiness for young children at developmental risk. The study took place in 29 Head Start classrooms operated through a public school system in a Midwestern state over the course of 4 years. Classrooms were housed in 21 different elementary school buildings and were in session during the academic year, 5 days each week, for 4 hours each day. All classrooms were of high quality as evidenced by their NAEYC-accreditation and all utilized the High/Scope curriculum (Hohmann & Weikart, 2002), which was implemented to support and enhance children’s overall development including language and literacy skills. Classrooms were inclusive settings, averaging 18 to 20 children from 3 to 5 years of age. At least 10% of the children in classrooms were identified as having disabilities or developmental delays or challenges in English language learning. Each classroom had at least one full-time, state-certified lead teacher with specialization in early childhood education and one full-time paraprofessional with child development credentials or training.

Standard (i.e., business as usual) services to involve parents in programmatic activities included an average of four 60-minute home visits each academic year, parent teacher conferences twice each year, and monthly family socialization activities at the school and in the community. The Head Start agency was committed to family involvement, particularly around activities that strengthen language and literacy. Preschool teachers were expected to communicate with families through the scheduled programmatic activities, as well as informal contacts at drop-off and pick-up times, weekly classroom newsletters, and occasional informal notes or telephone calls.

Participants

The participants in the present study were children enrolled in Head Start, their parents, and their classroom teachers. Table 1 summarizes child and parent demographic information at the baseline assessments.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Child and Parent Participants by Group and Overall at Baseline

| Control n = 101 |

Children Treatment n = 116 |

All N = 217 |

Control n = 100 |

Parents Treatment n = 111 |

All N = 211 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | (in months) | (in years) | ||||

| Mean | 43.18 | 42.94 | 43.05 | 28.55 | 30.24 | 29.44 |

| Range | 36.5-52.6 | 35.9-51.8 | 35.9-52.6 | 19-51 | 19-62 | 19-62 |

| SD | 3.69 | 3.47 | 3.57 | 6.75 | 8.39 | 7.69 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 44.6% | 56.9% | 51.2% | 7.0% | 3.6% | 5.2% |

| Female | 55.4% | 43.1% | 48.8% | 93.0% | 96.4% | 94.8% |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White/Non-Hispanic | 29.0% | 34.2% | 31.8% | 44.0% | 49.1% | 46.7% |

| African American | 15.0% | 19.8% | 17.5% | 14.0% | 18.2% | 16.2% |

| Latino/Hispanic | 31.0% | 22.5% | 26.5% | 31.0% | 22.7% | 26.7% |

| American Indian | 4.0% | 1.8% | 2.8% | 3.0% | 3.6% | 3.3% |

| Asian American | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 2.0% | 0.9% | 1.4% |

| Other | 20.0% | 20.7% | 20.4% | 6.0% | 5.5% | 5.7% |

| Does not Speak English | 40.0% | 25.7% | 32.5% | |||

| Parent Concern about Development | 22.3% | 27.1% | 24.9% | |||

| Teacher Concern about Development | 9.6% | 10.4% | 10.0% | |||

| Identified Disability | 14.6% | 10.0% | 12.1% | |||

| Referred for MDT Evaluation | 13.3% | 8.5% | 10.7% | |||

| Parent Education Level | ||||||

| Less than High School (At Risk) | 26.0% | 27.3% | 26.7% | |||

| High School Diploma (Not At Risk) | 14.6% | 8.2% | 11.2% | |||

| GED (Not At Risk) | 9.4% | 8.2% | 8.7% | |||

| Some College/Training (Not At Risk) | 34.4% | 35.5% | 35.0% | |||

| Two-year College Degree (Not At Risk) | 8.3% | 9.1% | 8.7% | |||

| Four-year College Degree Or More (Not At Risk) | 7.3% | 11.8% | 9.7% | |||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single, Not With Partner | 40.0% | 56.8% | 48.8% | |||

| Number of Adults in the Home | ||||||

| Mean | 1.76 | 1.73 | 1.75 | |||

| SD | .70 | .74 | . 72 | |||

| Parent Work Status | ||||||

| Employed | 56.7% | 57.7% | 57.2% | |||

| Unemployed - In School | 20.0% | 15.4% | 17.5% | |||

| Unemployed | 23.3% | 26.9% | 25.3% | |||

| Parent Overall Health Status | ||||||

| Excellent | 14.1% | 24.3% | 19.5% | |||

| Very Good | 26.3% | 37.8% | 32.4% | |||

| Good | 42.4% | 27.0% | 34.3% | |||

| Fair | 13.1% | 7.2% | 10.0% | |||

| Poor | 4.0% | 3.6% | 3.8% | |||

Child participants

Two hundred seventeen children ranging in age from 35.94 to 52.63 months at baseline (mean age = 43.05 months; SD = 3.57) served as participants. Fifty-one percent of child participants were boys; 49% were girls. According to parent report, slightly under one-third of child participants were White/non-Hispanic, 27% were Hispanic/Latino, 18% were reported to be African American/Black, 3% were American Indian/Native Alaskan, and 21% reported their children’s racial background as “other.” The primary language spoken by 76% of children was English, and 19% spoke primarily Spanish. Arabic, or a combination of languages, was spoken in 5% of child participants’ households. Twelve percent of child participants had an identified disability and another 11% had been referred for multidisciplinary team (MDT) evaluations at the start of the study. Teachers reported developmental concerns for 10% of the children whereas parents reported concerns for 25% of the children. All children were enrolled in the study upon their entry into Head Start (age 3) with the intent that they would receive services from a teacher who was trained and supported in the Getting Ready intervention for their entire 2-year preschool experience.

On occasion, students changed classrooms within the Head Start agency. Specifically, 32.5% switched teachers at some point during Head Start. Of these, 93.6% remained in the same condition (treatment or control) and were retained in the study. Alternatively, 6.4% switched conditions and were therefore dropped from the study. Children who left the Head Start program altogether were no longer included in active data collection efforts for the study.

Parent participants

Two hundred eleven parents completed parent questionnaires; 95% were female with the majority (87.2%) identifying as mothers, 4.7% were fathers, 3.3% were grandmothers, and 4.6% were related to the child in another way (e.g., as a grandfather, stepmother, or foster mother). The mean age of parent participants was 29.44 years. Forty-seven percent identified themselves as White, non-Hispanic, 27% as Hispanic/Latino, 16% Black/African American, 3% as American Indian/Alaska Native, 1% Asian American, and 6% other. Forty-nine percent reported being single or not with a partner. Twenty-seven percent of parents had not received a high school diploma or GED.

Head Start teacher participants

Twenty-nine Head Start teachers participated in the study (i.e., 13 in the treatment group; 16 in the control group). Twenty-five completed the teacher demographics questionnaire. All teachers had at least a bachelor’s degree, and 12.5% held an advanced graduate degree. Teachers were required to hold a state teaching certificate in Early Childhood Education. All were female, and their mean age was 36.05 years (SD = 11). Ninety-one percent of the teachers reported to be White, and 9% reported to be Hispanic/Latino. Teachers had an average of 9.4 years experience working in early childhood settings (SD = 8.3 years). In general, teacher participants were involved in the study for 4 years.

Measurement of Study Variables

The Teacher Rating of Oral Language and Literacy (TROLL; Dickinson, McCabe, & Sprague, 2003) and the Preschool Language Scale – Fourth Edition (PLS-4; Zimmerman, Steiner, & Pond, 2002) were used to evaluate the effects of the intervention on children’s language and literacy skills. These measures were multi-source and multi-method, including both teacher-report and direct child assessment components.

The TROLL is a 25-item measure designed to objectively evaluate preschool children’s (ages 3 through 5 years) development of language and literacy skills across three constructs (i.e., Language Use, Reading, and Writing). Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale or rubric (1 = never, limited; 4 = often, proficient) and enable teachers to rate children’s language- and literacy-related skills and describe their literacy-related interests. Each of the ratings is based on clearly defined observable indicators of language- and literacy-related skills. Mean scores across items were used for each subscale.

Dickinson and colleagues (2003) reported Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .77 to .92 for TROLL subscales based on a sample of 534 preschool children. Cronbach’s alphas for our sample include Language Use (8 items, α = .91 for our sample; e.g., “Child communicates personal experiences in a clear and logical way”); Reading (11 items α = .84; e.g., “Child remembers the story line or characters in books that he or she heard before, either at home or in class”); and Writing (6 items, α = .76; e.g., “Child writes other names or real words”). The only validity evidence provided by the authors is confirmation that the constructs measured by the TROLL address the speaking and listening skills listed in the Head Start standards..

The Preschool Language Scale – Fourth Edition (PLS-4; Zimmerman et al., 2002) is a standardized instrument (producing norm-referenced scores with M = 100 and SD = 15) that has been widely used to assess children’s language development. The PLS-4 has two core language subscales, Auditory Comprehension and Expressive Communication. To ease the assessment burden on children, only the Expressive Communication subscale was used in this study. Similar to the TROLL Language Use scale, the Expressive Communication subscale measures how well children communicate with others (e.g., makes sounds and responds to their caregiver), but it does so via a direct child assessment (versus teacher report). Tasks assessing the children’s abilities to make sounds, name items and actions, and communicate expressively through storytelling are also included on this subscale. The PLS-4 standardization group included a representative sampling based on the 2000 census; 17% of the norming sample was Hispanic children. Psychometric evaluations indicate a reliability coefficient of α = .91 for the Expressive Communication subscale (Zimmerman et al., 2002). Validity evidence supporting use of the PLS-4 scores is substantial. For example, a study investigating the differential item functioning of the PLS-4 found no evidence of cultural bias between Hispanic and European American children from low-income families (Qi & Marley, 2009). Additional validity evidence is presented in the PLS-4 administration manual (Zimmerman et al., 2002).

Moderators

Moderators investigated in this study included both family variables and child variables, identified from family and teacher survey data. Family variables that were investigated as likely moderators of the effectiveness of the intervention were baseline reports of parent education risk (i.e., at risk due to lack of high school diploma or GED, or not at risk), parent health (one item rated on a 5-point scale, from excellent to poor), the number of adults in the home (rated on a continuous scale), and household income (as reported by parents). Child characteristics that were investigated were (a) indication (at baseline) that the child did not speak English upon entry into preschool based on parent response to the survey question: Does your child speak English? and (b) developmental concern as noted by parent or teacher report of identified disability, referral to MDT for evaluation, or reported concerns about child’s development.2 General concern for development was of interest to capture all children for whom developmental delays may be imminent. Because interventions are often put in place in Head Start classrooms to support children prior to identification for special services, this operationalization captures more children who would be showing concerns than MDT identification alone. All child moderators were coded with 0 when absent and 1 when present.

Procedures

Recruitment of participants and assignment to experimental conditions

In the Spring of an academic year, Head Start teachers were approached by members of the research team in a large staff meeting to introduce them to the project. The following Fall, prior to the beginning of the preschool year, meetings were held with small groups of teachers to inform them of the general goals and expectations of the project, answer procedural questions, and solicit informed consent. They were assured that participation was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time without negative employment repercussions. Signed, informed, voluntary consent was attained from teachers at this time.

In nine cases, two or more Head Start classrooms were housed in the same building. Therefore, random assignment was made (after consents were obtained) at the building level to avoid contamination across conditions. The research team, including the principal investigators and the project director, randomly generated assignments of building to conditions, resulting in teacher assignment to conditions. Once the randomization was complete, assignments were shared with school district administrative personnel.

Eligible parents in both the treatment and control groups received information on the project from their child’s Head Start teacher. Because the purpose of this study was to determine the effects of the intervention on readiness skills associated with language and literacy development over 2 years during the full course of children’s Head Start experience, only children who were 3 years of age and eligible for 2 academic years of Head Start program services upon program entry were invited to participate in the study. Parents of all children who met these criteria were invited to participate by their child’s teacher, typically in the fall semester of each academic year. Only families who could speak English, Spanish, or both were recruited for study participation to assure successful administration of assessments, surveys, and coding of data. Parents were assured that their participation was voluntary and that their agreement to participate or decision to withdraw in no way affected their Head Start program services. Parents were not made aware of their condition assignment. From the perspective of the parent, the requirements for participation in the treatment and control groups were identical.

Upon parents’ verbal consent to teachers, a member of the research team contacted each interested parent and gathered informed written consent. Ninety percent of parents invited by Head Start teachers agreed to participate in the study. There were no differences in levels of consent obtained for treatment versus control conditions. Family assignment to treatment or control condition was dependent on teacher and building assignment to condition; thus, all children and families within the same building were assigned to the same experimental condition, resulting in a hierarchically nested design. Children’s assignment to a classroom was made by district administration prior to teacher assignment to a condition. That is, class lists were generated in the summer preceding teacher assignment to control or treatment condition. Thus, assignment of children and families to intervention condition was not driven by any specific family or child need for services. No significant differences were identified at baseline between treatment and control participants on gender, ethnicity, parental education risk, child age or parent age, disability or developmental concerns, indicating demographic equivalency of the groups at baseline.

Data were collected on four assessment occasions over a 2-year period for all participants, representing their entire experience in Head Start during which time teachers in the treatment condition utilized the Getting Ready approach. Baseline data were collected at the point at which parents and children were first enrolled in Head Start and collected in the Fall and Spring for 2 consecutive academic years and for three cohorts of children and families. Parents completed (a) a questionnaire (including demographic child and family information) at each data collection point lasting 25 to 40 minutes and (b) a video-recorded parent–child observation session lasting 15 to 30 minutes, depending on the age of the child. Bilingual English–Spanish-speaking data collectors administered assessments with Spanish-speaking parents. Assessments were conducted at a location convenient for the family, including the children’s schools, other community locations (e.g., library study rooms), or the families’ homes. At each assessment occasion, families received a gift card to a local retailer.

Child assessments were conducted during the typical preschool classroom day at the school site. Research assistants were trained to administer the PLS-4, which was conducted in English with all children. For children from Spanish-speaking families, child assessments were conducted by bilingual assessors who greeted the child and conversed in Spanish prior to the assessment as a strategy to build rapport and put the children at ease.

At the time of each child assessment, Head Start teachers were provided with a questionnaire for each child. Teachers completed the questionnaires independently within 2 weeks of the family assessment. The teachers then either returned the questionnaires to the researchers via mail or returned them to a research assistant directly. Completion time for the teacher questionnaire was approximately 20 minutes per child, twice per year. Teachers were compensated for their time in the form of a monetary stipend.

Getting Ready intervention procedures

The primary context for teachers’ use of the Getting Ready strategies was a 60-minute home visit conducted, on average, 8.35 times over 2 years (SD = 3.78; range = 1–19). The Getting Ready intervention was structured to provide opportunities for professionals to support and enhance the quality of parent–child interactions and learning experiences in daily routines and to create a shared responsibility between parent and professional to influence children’s school readiness (Sheridan et al., 2008). With the goal of encouraging parental warmth and sensitivity, support of their child’s autonomy, and participation in their child’s learning, the Getting Ready approach provided a structure for teachers to (a) focus the parent’s attention on their child’s strengths, (b) share and discuss observations about their child, (c) discuss developmental expectations and goals, (d) provide developmental information, (e) make suggestions, and (f) brainstorm collaboratively with parents around issues related to their child’s social, cognitive, or language development and learning (for further detail, see Sheridan et al., 2008). Teachers were also encouraged to use these strategies during family socializations at school and during any opportunity available during interactions with parents at drop-off and pick up times and through notes and phone calls.

The format and structure of home visits is outlined in Table 2. Home visits were approximately one hour in duration and were conducted with at least one parent, the Head Start teacher, and the child. In cases where other adults or caregivers were present in the home, they were invited to participate. When a language other than English was spoken by the family, a district interpreter familiar to the family accompanied the teacher and provided translation. As part of their process of interacting with parents, teachers took opportunities to affirm the parents’ competence in supporting or advancing children’s abilities, ask parents for their reflections and ideas related to children’s recent learning needs and interests, and provide feedback and in vivo suggestions as appropriate to draw the parents’ attention to their own actions and resultant child behaviors or skills. Teachers also promoted parent–child interactions during home visits through modeling and engaging in mutual goal setting. A home–school plan was created jointly by teachers and parents to lay out next goals for their children, and specific practices were outlined for each adult partner to use in their respective settings to promote children’s progress towards the goals.

Table 2.

Structure of the Collaborative Getting Ready Home Visit

| Opening (Establishing the Partnership) |

Discuss events since last visit. Ask open ended questions about:

|

| Ask questions to help caregiver identify a priority for visit; supplement as needed based on previous plans/conversation |

Discuss and clarify the purpose of this visit

|

| Agree to roles each will play in the various activities |

| Main Agenda for the Visit (Observing and Supporting Parent-Child Interactions) |

Observe the caregiver-child dyad for the caregiver to:

|

Closing (Action Planning)

|

Professional development: Training and coaching

The primary purpose of professional development in the Getting Ready intervention was to support teachers’ competence and confidence in interactions with parents, so as to support parents’ own competence and confidence in their interactions with their children. Professional development was conducted via face-to-face training and coaching. Head Start teachers in the treatment group were initially introduced to the Getting Ready intervention through a 2-day training institute. The content of training was focused on helping teachers understand the Getting Ready model and strategies; their use of these strategies during home visits, socializations, and other interaction opportunities with families and children; and their ability to integrate important family-centered practices into instruction (see Sheridan et al., 2010). Head Start teachers in the treatment group were supported in the implementation of the Getting Ready intervention through formalized coaching with a project coach twice per month. The caseload per coach ranged from 10 to 13 teachers. One 60-minute coaching session each month was individualized and the other session took place in a 90-minute group format with three to five Head Start teachers. For further information on coaching within the Getting Ready study, see Brown, Knoche, Edwards, and Sheridan (2009) or Sheridan et al. (2010).

Control teachers also participated in training sessions to minimize awareness of group assignment and introduce an experimental control for attention provided to the treatment group. The content of training for control group participants was child-focused as compared to family- and child-focused in the treatment group. The child-focused content for the control group included child development topics, such as social-emotional development in young children. The focus for the control group included child-focused approaches the teacher could use to support social-emotional development. Alternatively, the training for the treatment group did not address teacher skills for working with children directly, but rather, it focused on how teachers could engage families to support positive development in their children across a range of developmental domains (e.g., cognitive, linguistic and social-emotional). Control teachers continued to receive agency supervision on their work with families and children, on average, monthly.

Fidelity of Intervention Implementation

The dosage of intervention, the adherence to the general strategies of the Getting Ready intervention, and the quality with which Head Start teachers promoted parent engagement were considered important indicators that the treatment was implemented as intended. To differentiate between treatment and control conditions, data on these indicators were collected across groups (Dane & Schneider, 1998). Dosage was defined as the number of home visits received by families over the 2-year period they were enrolled in Head Start and receiving the Getting Ready approach to services. Adherence and quality (Dane & Schneider, 1998) were coded objectively from digital video records of the teachers’ behaviors on randomly sampled home visits (Knoche et al., 2010) after they had been involved in Getting Ready activities for at least 4 months. When considered analytically, the product of adherence and quality was computed to create a variable accounting at once for both quality and quantity of strategy use. A full description of procedures used to assess and document intervention implementation fidelity is available in Knoche et al. (2010).

Study Design

Data were analyzed using a hierarchical linear modeling framework (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), which takes into account the clustered nature of the design. Because of limited variability in outcome variables at the level of the school, no school-level random effects were found for intercepts or slopes, resulting practically in a three-level model accounting for the teacher level of nesting within the HLM. The longitudinal analytic model is structured as time points within students, nested within teachers. In addition to the residual variance at level 1, variance components for student intercepts, student slopes, and teacher intercepts were estimated to account for nesting. Parental education, child language reported as other than English, and child gender were included as covariates. The combined analytic model is as follows:

| (1) |

where the parameter of interest, γ101, the group*time interaction, represents the difference in slopes between the intervention and control groups. Variance components are included to account for intercept variation at the child-level (r0ij), variation in slopes at the child-level (r1ij), and intercept variation at the teacher-level (u00j).

The HLM accounts for missing data through the use of full-information maximum likelihood (FIML; Enders, 2001). All analyses were carried out using the MIXED procedure in SAS version 9.2. Through the use of FIML in the HLM framework, all participants with at least one measurement occasion are retained in the data analysis in contrast to procedures such as listwise deletion where any participant with a missing observation would be effectively excluded from the analysis. FIML maximizes a sum of casewise likelihood functions where each case- or participant-specific likelihood function can be comprised of varying numbers of measurement occasions. Thus, individuals with missing data at later time points still contribute by providing information for the estimation of model parameters. No cases were excluded in the main effect models due to missing values on predictor variables. Complete data were available for the three covariates included in the analyses, as they are child- and parent-level variables (data that are collected at baseline and are invariant over time). No teacher-level covariates were included in the models. Over the course of the study a fair amount (32.5%) of children moved to new classrooms and teachers. The analysis took into account occasion-specific clustering of children and parents within teachers, making the analysis a cross-classified model at the teacher level.

In the initial set of analyses, four separate main-effect HLMs were performed, one for each outcome variable of interest (i.e., PLS-4 Expressive Communication and three TROLL construct subscales). To protect against inflation of Type I error, a procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR; Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) within this —family or group of four comparisons was implemented. The FDR is the proportion of rejected null hypotheses that are rejected erroneously (i.e., false discoveries).

Second, a set of exploratory analyses was also conducted to investigate potential moderators of the Getting Ready intervention. Tests of moderation of the time*group interaction were carried out by adding the moderator in question as a time*group*moderator effect, including the main effect of the moderator and each two-way interaction. The three-way interaction term assesses the extent to which the newly added independent variable moderates the time*group interaction. A significant positive interaction indicates the treatment effect is significantly higher at higher levels of the moderator variable. The model for testing moderation (using parent education as an example) is as follows:

| (2) |

where the parameter of interest, γ141, the moderator*group*time interaction, represents how the difference in slopes between the intervention and control groups varies as a function of the moderator. In this example, a significant parent education*group*time interaction would indicate that the effectiveness of the intervention is significantly different at different levels of parent education.

Results

Descriptive statistics across all outcome measures are presented in Table 3. Parameter estimates for the condition*time interaction effect, condition, time, and covariate main effects, as well as the standardized effect size3 for the interaction term are presented in Table 4. The parameter estimate for the time*group interaction can be interpreted as the difference in the per-month growth rate in scores between the control and treatment groups. In these analyses, time is coded as the number of months since randomization, or baseline. No significant differences were observed in TROLL scores at baseline between the two groups, as evidenced by the non-significant group differences in intercepts (i.e., the Group (T-C) variable in Table 4). The treatment group was found to have significantly higher PLS-4 Expressive Communication scores at baseline than the control group. The analytic model controls for the intercept and group differences in intercepts as it assesses slope differences between groups over time.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for PLS-4 Expressive Communication and TROLL Scales Over Time Across Treatment and Control Conditions

| Time 1 M (SD) |

Time 2 M (SD) |

Time 3 M (SD) |

Time 4 M (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLS-4 ECa | ||||

| Treatment | 101.33 (16.94) | 101.41 (15.27) | 100.75 (15.16) | 100.84 (15.53) |

| Control | 97.44 (17.52) | 95.27 (17.37) | 95.45 (18.52) | 96.65 (19.01) |

| TROLL Language Useb | ||||

| Treatment | 2.35 (0.64) | 2.82 (0.61) | 3.13 (0.54) | 3.39 (0.56) |

| Control | 2.47 (0.58) | 2.85 (0.61) | 3.02 (0.58) | 3.26 (0.63) |

| TROLL Readingb | ||||

| Treatment | 1.93 (0.41) | 2.39 (0.48) | 2.62 (0.49) | 3.0 (0.53) |

| Control | 1.99 (0.37) | 2.38 (0.39) | 2.46 (0.43) | 2.79 (0.43) |

| TROLL Writingb | ||||

| Treatment | 1.32 (0.4) | 1.9 (0.62) | 2.2 (0.68) | 2.73 (0.68) |

| Control | 1.38 (0.35) | 1.85 (0.55) | 2.07 (0.61) | 2.56 (0.62) |

Note.

Preschool Language Scale-4th ed., Expressive Communication scale. Standard scores with M = 100; SD = 15

Teacher Rating of Oral Language and Literacy. Raw scores on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, limited; 4 = often, proficient)

Table 4.

Group × Time Interaction and Main Effects of the Getting Ready Intervention

| Outcome | Estimate | SE | df | t value | p value | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLS-4 Expressive Communicationa | ||||||

| Intercept | 101.940 | 1.800 | 205.670 | 56.780 | <.001 | |

| Education Risk | −10.250 | 2.260 | 190.860 | −4.550 | <.001 | |

| Other Language | −10.790 | 2.180 | 196.590 | −4.950 | <.001 | |

| Child Gender | −0.060 | 0.093 | 325.915 | −0.644 | .520 | |

| Time | 0.099 | 0.077 | 115.844 | 1.276 | .205 | |

| Group (T-C)b | 5.020 | 2.190 | 187.780 | 2.290 | .020 | |

| Time (T-C)c | −0.098 | 0.106 | 116.697 | −0.925 | .357 | −0.64 |

| TROLLd Language Use | ||||||

| Intercept | 2.610 | 0.070 | 221.040 | 38.590 | <.001 | |

| Education Risk | −0.250 | 0.090 | 189.980 | −2.950 | <.001 | |

| Other Language | −0.200 | 0.080 | 195.630 | −2.460 | .010 | |

| Child Gender | 0.003 | 0.004 | 307.116 | 0.891 | .373 | |

| Time | 0.046 | 0.003 | 158.936 | 13.139 | <.001 | |

| Group (T-C) | −0.110 | 0.080 | 200.750 | −1.300 | .200 | |

| Time (T-C) | 0.014 | 0.005 | 147.599 | 2.967 | .004 | 1.11 |

| TROLL Reading | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.851 | 0.088 | 207.551 | 21.044 | <.001 | |

| Education Risk | 0.021 | 0.009 | 194.745 | 2.447 | .015 | |

| Other Language | −0.064 | 0.057 | 190.764 | −1.107 | .270 | |

| Child Gender | 0.004 | 0.003 | 319.313 | 1.067 | .287 | |

| Time | 0.045 | 0.003 | 145.158 | 14.323 | <.001 | |

| Group (T-C) | −0.065 | 0.053 | 197.168 | −1.219 | .224 | |

| Time (T-C) | 0.015 | 0.004 | 138.326 | 3.617 | .000 | 1.25 |

| TROLL Writing | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.420 | 0.050 | 293.730 | 28.140 | <.001 | |

| Parent Education | −0.140 | 0.070 | 283.690 | −2.120 | .030 | |

| Other Language | −0.070 | 0.070 | 277.160 | −1.040 | .300 | |

| Child Gender | 0.008 | 0.004 | 330.006 | 1.799 | .073 | |

| Time | 0.063 | 0.004 | 164.521 | 14.762 | <.001 | |

| Group (T-C) | −0.050 | 0.060 | 281.410 | −0.920 | .360 | |

| Time (T-C) | 0.017 | 0.006 | 154.481 | 3.023 | .003 | 0.93 |

Note.

Preschool Language Scale-4th ed., Expressive Communication scale. Standard scores with M = 100; SD = 15

Group (T-C) is the difference between treatment and control groups in intercepts

Time (T-C) is the difference between treatment and control groups in slope means (the time*group interaction coefficient)

Teacher Rating of Oral Language and Literacy. Raw scores on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, limited; 4 = often, proficient)

Attrition

This study was conducted over 2 academic years for enrolled families. Not all families were retained, however, throughout the entire study period. Fifty-four percent of families were retained through the fourth assessment occasion, which occurred approximately 18 months after the baseline assessment. Attrition from the study occurred when families left the Head Start program. The difference in attrition rates between the two experimental conditions (control = 47.5%, treatment = 44.8%) was not statistically significant, χ2(N = 217, df = 1) = 0.158, p = .691. Additional non-significant chi-square tests indicate that the participants who left the program, and thus the study, did not differ significantly from those that remained in the study on key demographic characteristics such as gender and primary language used at home.

The possible impact of attrition was assessed by comparing baseline TROLL and PLS-4 Expressive Communication scores between children who completed four measurement occasions across two academic years (labeled “completers”) and those who did not (labeled “non-completers”). Two-tailed t-tests (α = .05) indicate that non-completers were not significantly different from completers at baseline in any of the three TROLL subscales or the PLS-4 Expressive Communication measure4. These results suggest that missing data can be considered missing at random (MAR) and did not affect or bias the estimation of the effectiveness of the Getting Ready intervention on the outcomes of interest.

Direct Effects of the Getting Ready Intervention

Teacher ratings of children’s language and literacy

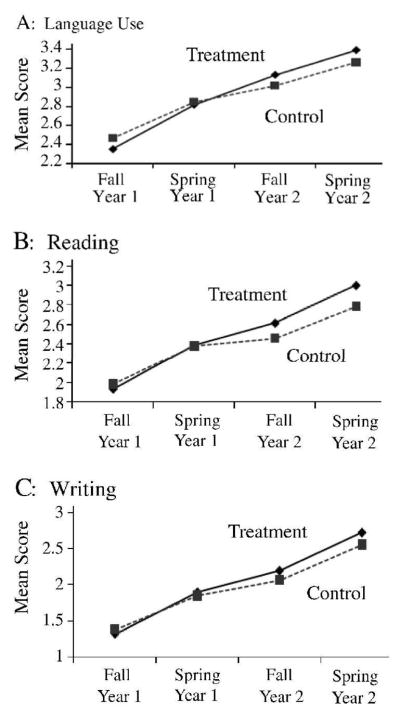

Changes in teacher ratings of children’s oral language use, reading, and writing as a function of the Getting Ready intervention were assessed with the TROLL. Ratings on the TROLL items ranged from 1 (never, limited) to 4 (often, proficient), and mean scores across items were used for each subscale, as opposed to sums of items scores, in order to account for missing item-level data.5 Results are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Change in scores for treatment and control groups over four assessment occasions for TROLL Language Use (Panel A), Reading (Panel B), and Writing (Panel C).

Significant differences were observed between treatment and control participants in the rate of change over time on teacher reports of language use, reading, and writing. Although the control group significantly improved on each subscale, the intervention group experienced more growth over time. Preschool children in the Getting Ready intervention demonstrated significantly enhanced gains in level of oral language use over time compared to controls as measured by the Language Use subscale of the TROLL, γ = 0.014, t(148) = 2.97, p = .004 d = 1.11. The parameter estimate for the time*group interaction indicates that the treatment group gained, on average, 0.014 points more per month than control children on the language use scale. Over the 18-month intervention period, the treatment group gained 0.252 points more, on average, than the control group. In percentile terms, d = 1.11 suggests that the growth in oral language for the average child in the treatment group exceeds 87% of control group participants.

The treatment group’s rate of change in TROLL Reading scores was found to be significantly different from that of the control group, γ = 0.015, t(138) = 3.62, p = .000, d = 1.25. An average child in the Getting Ready intervention outperformed 89% of participants in the control group after intervention, a net gain of 0.27 points more than the control group. Furthermore, the treatment group demonstrated significantly greater improvement over time on the TROLL Writing scale, γ = 0.017, t(155) = 3.03, p = .003, d = 0.93, outperforming approximately 82% of children in the control condition, a net gain of 0.306 points more than control group children.

Children’s measured expressive language

The analytic model revealed that growth in PLS-4 Expressive Communication scores was not found to differ significantly between the intervention and control groups.

Covariates and Type I error control

All main-effect analyses included child gender, parent education, and child primary language (reported as other than English) as covariates. Across all analyses, child gender was not found to be a significant covariate, whereas parent education and child primary language nearly always accounted for a significant amount of variation in outcome scores but did not affect the estimation of growth rates. In the final analytic models, the significance of the treatment effect for all three TROLL subscales and the PLS-4 Expressive Communication scores remained unaffected by the addition of child gender, parent education, and child primary language as control variables.

As previously indicated, the Type I error control was performed through the use of the Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) sequential Bonferroni-type procedure. Each of the three TROLL subscale p values fell below the incremental critical p values for FDR control, suggesting that the findings are interpretable and not due to chance. For the PLS-4 Expressive Communication scores, p values fell above the incremental critical p values for FDR control. As described in the following section on moderated intervention effects, the same method of covariate analysis was undertaken. Parent education and child’s primary language did relate significantly to the outcome of interest, but parameters were not affected.

Intraclass correlation coefficients

Most of the variability in outcomes is attributable to level 2 (child or parent). The intraclass correlation coefficient for PLS-4 Expressive Communication scores indicated that 80% of the variability in scores was attributable to the individual child. Correlation coefficients ranged from 0 to 63% for TROLL scores. Intraclass correlations were assessed at baseline with an unconditional means model. There was also a considerable amount of variability in outcomes at the teacher level (level 3). Although the proportion of variability in the PLS Expressive Communication scores attributable to teachers was near zero, the proportion of variability in TROLL scores attributable to teachers ranged from .13 (Language Use) to .41 (Writing). These results highlight the importance of accounting for dependence at the levels of both individual children and teachers, which was accomplished through the use of the HLM framework.

Moderated Effects of the Getting Ready Intervention

Possible moderators of the intervention effectiveness for both TROLL and PLS-4 were further examined. The two child variables—the presence of a developmental concern (per parent or teacher report) and entering Head Start not speaking English (per parent report)—moderated the effects of the intervention in distinctive ways. Specifically, when a developmental concern was evident upon entry into preschool, children in the treatment group consistently demonstrated significantly greater gains on all language and literacy outcomes relative to when no concerns were noted, and compared to children not receiving the Getting Ready intervention, PLS-4 Expressive Communication, γ = 0.859, t(136) = 2.05, p < .05; TROLL Language Use, γ = 0.033, t(108) = 2.03, p < .05; TROLL Reading, γ = 0.034, t(144) = 2.2, p < .05; and TROLL Writing, γ = 0.04, t(164) = 2.18, p < .05. Alternatively, when children were reported by their parent as not speaking English upon entry into preschool, they made greater improvements on the TROLL Language Use, γ = 0.048, t(139) = 2.73, p < .05, and TROLL Reading scales, γ = 0.034, t(149) = 2.13, p < .05, relative to children who reportedly spoke English and relative to controls. These outcomes suggest that the rate of growth was greater for the children who entered the intervention at greater disadvantage due to developmental concern or language spoken but not necessarily that their performance following treatment was greater than those who did not experience those same risk factors.

Family variables acted in unique ways, depending on the measure being used to document children’s growth. Parent education risk moderated the effectiveness on expressive language as measured with the PLS-4 Expressive Communication scale in that when parents had less than a high school education or GED, there was significantly less improvement in children’s expressive language as a function of the intervention, γ = −0.473, t(110) = −2.03, p < .05, relative to when the parents held at least a high school degree or GED and relative to the control group. Parent health moderated the intervention’s effect on TROLL Language Use scores such that when parents reported more health concerns, children made fewer improvements on the TROLL Language Use scale, γ = −0.012, t(134) = −2.75, p < .05. However, number of adults in the home moderated the effects of Getting Ready intervention on Language Use scores in a positive manner, γ = 0.015, t(157) = 2.26, p < .05; greater improvements on the Language Use scale were noted when more adults were residing in the home compared to fewer adults for children in the treatment group as compared to the control group (assessed on a continuous scale). Household income did not moderate the intervention’s effects.

Fidelity of Implementation and Dosage

Two metrics were used to consider fidelity as a moderator of the efficacy of the Getting Ready approach. First, dosage of intervention was defined as the number of home visits completed over 2 years of Head Start. Second, a joint index of adherence to strategy use and overall quality with which teachers promoted parent engagement was computed to account for the importance of both dimensions of fidelity simultaneously. There were significant differences between treatment and control groups in dosage, t(208) = 2.185; p < .05, with treatment group participants completing more home visits over 2 years, M = 8.35, SD = 3.78 for treatment and M = 7.23, SD = 3.6 for control. Likewise, significant differences between treatment and control groups were evident in the joint index of strategy use and overall quality, t(31) = 4.157, p < .001, with M = .157, SD = .06 for treatment and M = −.079, SD = .05 for control. Teachers did not change significantly over the course of the study in adherence/quality. Although both dosage and the joint index of quality and use of strategies were found to be significantly higher in the intervention group at baseline and throughout the study relative to the control group, neither was found to significantly moderate the effectiveness of the intervention.

Possible cohort differences in adherence/quality were assessed in a multilevel model, which accounted for some teachers being involved in multiple cohorts over the course of the study. No significant differences were found in adherence/quality as a function of cohort. Furthermore, although cohort accounted for intercept variance in two of the four outcome measures, cohort did not significantly moderate the effectiveness of the intervention.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the efficacy of a school readiness intervention (Getting Ready) on young children’s language and literacy skills as observed in the early childhood environment. Identifying effective strategies and programs to support children’s language and literacy is critically important given the strong link between a child’s early language and literacy skills and later school and reading success (National Early Literacy Panel, 2009; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005). Whereas efficacious classroom-based intervention models are increasingly available in the early childhood literature (e.g., Bierman et al., 2008; Pianta, Mashburn, Downer, Hamre, & Justice, 2008; Raver et al., 2008), relationships with and impacts on parents are rarely specified.

Among the well-researched models focusing on parent roles and specific developmental outcomes, structured curricula delivered by expert facilitators in a systematic, unidirectional, and prescribed fashion are the norm. For example, the Incredible Years program (Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2010) is a group-based parent training program wherein parents are taught, through a structured sequence of lessons, to manage children’s behaviors using effective parenting strategies. Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT; Hembree-Kigin & McNeil,1995) similarly focuses on teaching parents methods for interacting with their children as precursors to meaningful behavioral guidance and management. The Playing and Learning Strategies intervention (PALS; Landry, Smith, Swank, & Guttentag, 2008) is a systematic curricular approach aimed at developing affective bonds and responsive parenting behaviors. Hanen Centre’s It Takes Two to Talk program (Manolson, 1992) empowers parents to become children’s primary language facilitator through a series of group training and reflective video feedback sessions (Girolametto & Weitzman, 2006). Each of these expert programs is delivered to parents in efforts to change the way they interact with their children.

Relative to parent training models, less research has investigated consultative partnership approaches with families when children were enrolled in early childhood group settings, such as preschools. Getting Ready specifically targets the goals of supporting and strengthening parent engagement and home-school partnerships on behalf of preschool children’s development and school readiness. Thus, evaluating the efficacy of the Getting Ready intervention provides a way to examine whether school readiness can be enhanced through intervention focused on relationships between parents and children and relationships between parents and the children’s teachers. Because all children examined in this analysis were also participants in a high-quality, community-based program for preschool children at risk of school failure, the current study determined the value of meaningful parent engagement added by the Getting Ready intervention beyond the gains expected on the basis of child and parent participation in Head Start services. A related aim yet to be tested concerns whether the collaborative partnership formed via the Getting Ready approach serves to strengthen parents’ role constructs and practices beyond the Head Start years. Additional research will allow us to fully comprehend the unique benefits of early engagement on parents’ current and future behavior.

A multi-method approach was used to assess children’s outcomes, recognizing that teacher reports and direct assessments of children’s language may capture different and unique aspects of children’s development (Cabell, Justice, Zucker, & Kilday, 2009). Clear differences between treatment and control groups over time were observed on teacher-rated language and literacy outcomes in favor of the Getting Ready participants, relative to children in the control group. The addition of covariates (i.e., gender, parent education, and child primary language) did not undermine the significance of the treatment versus control differences on the three teacher-rated language and literacy outcomes. Noteworthy is the fact that both groups of children showed gains over time in their scores for language use, reading, and writing, as reported by their teachers. In fact, gains for children in the control group appeared generally consistent with those for treatment group children throughout the first year. Departures from the growth trajectory for the control group occurred during the summer months when Head Start programs were not in session. It is interesting to note that children in the Getting Ready condition continued to make gains during that time, which is possibly due to parents’ continued engagement in learning experiences even in the absence of a classroom program.

When children’s expressive language was directly assessed, relatively greater rates of improvement were seen for children for whom concerns were noted with development and for children whose parents had at least a high school diploma or GED. Rates of change on teacher reports of language use were most pronounced for children for whom there were expressed concerns about development, for children whose parents reported that their child did not speak English when they started preschool, and for children who resided with more than one adult in the home (versus only one). Less improvement was seen for children in the treatment group when parents reported problems with their own health. These findings are explored more fully below.

The early presence of concern about children’s development moderated virtually all of the outcomes of the Getting Ready intervention. When children entered preschool with pre-identified concerns (i.e., disability, referral for evaluation, or reports of concern), the effects of the intervention on all language and literacy outcomes were magnified, regardless of child gender, child primary language, or parent education. It is possible that the Getting Ready intervention may be particularly beneficial as an early intervention for children with developmental needs during the preschool period, a time when language development is most vulnerable. Efforts at reaching out to parents in the early stages of concern are not uncommon in early intervention programs (Weiss, Caspe, & Lopez, 2006), and the Getting Ready intervention provided a structure by which teachers could create and foster collaborative partnerships across home and school. That is not to say that such partnerships are unimportant for other children; rather, the existence of disabilities or developmental concerns may elucidate the benefits of positive collaboration between families and schools (Blue-Banning, Summers, Frankland, Nelson, & Beegle, 2004; Turnbull, Turnbull, Erwin, Sodak, & Shogren, 2010). The collaborative practices defining the Getting Ready intervention (e.g., providing structure for assessing children’s needs, setting goals, developing plans across settings, and monitoring progress) were likely useful for targeting the language and literacy needs of children with developmental delays.

Children’s primary language also moderated the effects of the Getting Ready intervention, in that children who did not speak English upon entering preschool (according to parents’ reports at baseline) experienced more gains on the teacher-rated oral language and reading scores than those who reportedly spoke English. This finding is encouraging and suggests that children who entered preschool reportedly not speaking English derived even greater benefits than others from the Getting Ready intervention. Alternatively, it is possible that the classroom preschool curriculum was even more effective with these children than it was with the children who entered preschool reportedly speaking English. The lack of substantiated evidence to document the degree of receptive and expressive English proficiency for the Spanish-speaking children as they began school prevents us from ascertaining the true role primary language played in influencing children’s response to the Getting Ready intervention.

Family factors, including parental education and health, also had implications on the effectiveness of the Getting Ready intervention, particularly around the oral language domain. Children in the treatment group experienced less growth in expressive language skills over the 2-year study when their parent reported achieving less than a high school diploma or GED. This finding is consistent with previous literature indicating that parental education is inversely correlated to children’s language and literacy development (Burchinal et al., 2002; Dollaghan et al., 1999). Additionally, parent health concerns reduced the effectiveness of the intervention on treatment group children’s use of expressive language. This finding is consistent with other research that has indicated with improved parent health, children’s outcomes also improve (Waylen & Stewart-Brown, 2009). Indicators of poor health and limited education are both markers of family risk that have repeatedly been shown to diminish outcomes for children (Gutman, Sameroff, & Cole, 2003). In contrast, the findings related to number of adults in the home suggest that having more rather than very few adults in the home may have served as a protective factor for children.

This study adds to the growing evidence base for the Getting Ready intervention on children’s school readiness skills. Previous studies have found positive results of the intervention in its ability to enhance children’s social–emotional skills relative to a control group (Sheridan et al., 2010). Others (e.g., Brown et al., 2009; Edwards et al., 2009; Knoche et al., 2010) have documented the changes produced in teachers’ beliefs and practices. The current study supports the effects of this same intervention in promoting teacher-reported language and literacy skill development, above and beyond what is being attained as a function of the Head Start preschool experience. Combined, these studies offer evidence of the utility of consultation models with parents to promote a wide range of developmental outcomes, relative to other models that focus solely on one developmental domain (e.g., communication or behavior) to the exclusion of others. The breadth and scope of developmental goals that can be achieved within the framework of the Getting Ready intervention appears to be among its strengths.

Several interpretations or explanations of the intervention’s effects on teacher-reported and direct assessments of children’s language and pre-literacy skills are possible. The first is that the intervention resulted in desired changes in teachers and parents; that is, that teachers receiving training and support from Getting Ready staff increased their capacity to interact with parents in ways that supported parent engagement and interaction with their children around language and literacy (Knoche et al., 2010), thereby increasing children’s language and literacy skills as observed in the classroom. The Getting Ready intervention may have provided a mechanism for teachers to transfer and reinforce the language and literacy focus of Head Start classrooms into home settings, which was not emphasized in home visits of control group teachers (Edwards et al., 2009).

Alternatively, other processes could be at work in the classrooms that account for the changes we found in the teachers’ ratings of language use, reading, and writing. For example, it is possible that even though children in both conditions received the same academic and socioemotional curriculum in their respective Head Start classrooms, variations in teacher background, teacher abilities, or both were confounded with treatment conditions. Statistical comparisons of treatment and control teachers found no significant differences on demographic characteristics6 or self-reported relationships with parents (Knoche et al., 2010), although we do not know if there were qualitative differences between groups. Due to random assignment, we expect any teacher differences that may be present at baseline would be due to chance.

Another possibility is that during the group and individual coaching sessions, teachers in the treatment condition may have shared strategies for supporting language and literacy development in the classroom, in addition to discussing methods of interacting with parents. In other words, teachers may have learned strategies in the training and coaching sessions that enhanced their classroom teaching, such as improvements in language and literacy instruction or in their ability to be good observers of children’s behavior in order to share information with families. Unfortunately, we do not have data on general classroom quality, or changes therein, that may be attributable to the intervention. However, Getting Ready project personnel served as coaches in all of the coaching sessions and provided extensive documentation of the content of discussions, and we would assert that any such discussions of curriculum were rare parts of the meetings. This assertion is partly corroborated by a qualitative study by Brown and colleagues (2009) who found that teachers in the treatment group felt strongly that the main benefit of their involvement was enhanced work with parents; teachers did not report improved or differentiated practices in the classroom or in their direct work with children.