Abstract

The rate of meiotic recombination is not a constant function of physical distance across chromosomes. This variation is manifested by recombination hot spots and cold spots, observed in all organisms ranging from bacteria to humans. It is generally believed that factors such as primary and secondary DNA sequence, as well as chromatin structure and associated proteins, influence the frequency of recombination within a specific region. Several such factors, for example repetitive sequences, gene promoters, or regions with the ability to adopt Z-DNA conformation, have been hypothesized to enhance recombination. However, apart from specific examples, no general trends of association between recombination rates and particular DNA sequence motifs have been reported. In this paper, we analyze the complete sequence data from human chromosome 22 and compare microsatellite repeat distributions with mitotic recombination patterns available from earlier genetic studies. We show significant correlation between long tandem GT repeats, which are known to form Z-DNA and interact with several components of the recombination machinery, and recombination hot spots on human chromosome 22.

The genetic map distance, based on recombination frequencies between genetic markers, was the earliest measure of distance between chromosomal elements. Early studies assumed that recombination events occur randomly along a DNA molecule and that the rate of recombination between markers should be proportional to their physical separation. However, with the availability of information about DNA sequence and physical maps, it became apparent that physical and genetic distances are not always connected by a simple linear relationship. Certain genes were found to be much closer together than was predicted from their genetic distance. Regions where recombination occurs significantly more frequently than expected are known as recombination hot spots. The existence of such hot spots was first shown in bacteriophage but has since been noted in bacteria, yeast, and mammals (Wahls 1998). In humans, the extensive sequencing efforts, accelerated recently by the Genome Sequencing Project, along with the construction of accurate radiation hybrid maps, have revealed the existence of numerous recombination hot spots.

Certain regions of increased recombination are associated with a particular physical location on a chromosome. For example, subtelomeric chromosomal bands undergo recombination at an elevated rate, whereas centromeric bands show a decreased frequency of recombination (Wintle et al. 1998). In addition, there exist sex-specific differences. In humans the frequency of recombination is generally higher in females than in males, but this sex-dependence varies between telomeric and centromeric locations (Li et al. 1998).

However, although some of the variation in recombination rates can be explained by position specificity, many true hot spots are small regions of elevated recombination frequency surrounded by areas with ordinary recombination rates. For example, studies of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in mice revealed the existence of a hot spot of only 1000 bp, which may account for up to 2% of recombinants on the entire chromosome (Kobori et al. 1986; Wahls 1998). It is believed that such hot spots must be caused by specific DNA sequence patterns and their interaction with the molecular recombination machinery.

Much of our knowledge of recombination specificity comes from work in bacteria, yeast, and cell culture. In those systems, the interaction of DNA and recombination proteins can be more easily dissected, and the predictions tested. Several recombinogenic DNA sequences have been proposed or identified. Work in the bacterium Escherichia coli led to the identification of the χ sequence (Smith et al. 1981) and the junction resolution sequence (Shah et al. 1994), which respectively serve to initiate and terminate the recombination process. In yeast, regions of enhanced recombination are frequently associated with double-strand chromosomal breaks, which are believed to be necessary for initiation of recombination (Pittman and Schiementi 1998). Although double-strand breaks often occur within gene promoters and susceptible regions can be identified by using a DNase hypersensitivity assay, no characteristic DNA sequence pattern has been associated with such regions. In higher organisms, studies in mice and humans indicate that repetitive tandem sequences may be responsible for recombination hot spots (Murray et al. 1999). One such type of repeat, a minisatellite repeat, has been observed within a hyperrecombinant region within the MHC locus (Wahls et al. 1990b). Subsequently, in human tissue culture a similar repeat has been shown to enhance recombination between plasmid vectors by more than tenfold. Another type of recombinogenic repeat, a dinucleotide (GT)n microsatellite, is the subject of this study and is discussed below.

Several copies of long (GT)n microsatellites are present within the hypervariable MHC locus (Hellman et al. 1988). Furthermore, a (GT)30 repeat, when subcloned into a yeast chromosome, enhances the frequency of meiotic recombination and gene conversion events in adjacent regions (Treco and Arnheim 1986). Finally, in human tissue cultures, the (GT)30 repeat also enhances recombination between plasmid vectors (Wahls et al. 1990a).

More information about the role of GT repeats in enhancing recombination is provided by biochemical in vitro experiments. Studies of the recombinase proteins RecA, Rad51, and hsRad51 (the evolutionarily conserved recombination proteins in bacteria, yeast, and human, respectively) revealed preferential binding of the enzymes to GT-rich sequences (Tracy et al. 1997; Biet et al. 1999). Moreover, branch migration, the process that extends the recombinant DNA molecule, is believed to be impeded by GT dinucleotide repeats, possibly leading to the resolution of the recombinant junction in the proximity of the repeat (Dutreix 1997). Finally, (GT)n repetitive sequences are known for their ability to form a left-handed helix structure (Z-DNA), which may alter the interaction between chromatids following a synapsis event (Wahls et al. 1990a).

Although several pieces of evidence implicate factors such as GT repeats in increasing recombination rates, their effect has been shown only in isolated cases. Moreover, the results from in vitro and single-cell model system studies do not always correspond to real-life situations. An ideal experiment would directly test for the presence of GT repeats in recombination hot spots, as well as their absence in recombination cold spots, across a long DNA segment. The completion of sequencing of human chromosome 22 (Dunham et al. 1999), combined with the already available genetic maps (Dausset et al. 1990; Dib et al. 1996; Broman et al. 1998), provides the first opportunity to analyze the results of such an experiment. In this paper, we present the analysis of recombination patterns across chromosome 22 and their correlation with GT repeat density.

RESULTS

We identified the physical positions along the chromosome 22 sequence for 59 markers from the Marshfield genetic map (see Methods section). We then scanned the chromosome 22 sequence for the presence of microsatellite (di-, tri-, and tetranucleotide) repeats. We used a critical alignment score of 50 (see Methods section) as a cutoff for reporting repeats. This corresponds to lengths of 12.5, 8.3, and 6.3 perfect repeat units for di-, tri-, and tetranucleotides, respectively. A certain number of mismatches and deletions were allowed for longer repeats (see the Methods section for the criteria used).

We used linear regression analysis to detect correlation between the relative frequency of recombination within a chromosomal region and the number of microsatellite repeats within that region. The resulting variables of interest, the recombination intensity (defined as the genetic distance in cM divided by the physical distance in Mb, for each intermarker interval) and microsatellite repeat density (defined as the total number of microsatellite repeats within an intermarker interval divided by the length of the interval in Mb), are shown in Table 1 (GT microsatellites only). The complete results of the regression analysis are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

GT Repeat Density Versus Recombination Intensity

| Intermarker intervala | Sex-averaged | Female-specific | Male-specific | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT repeat density (repcats/Mb) | recombination intensity (cM/Mb) | GT repeat density (repeats/Mb) | recombination intensity (cM/Mb) | GT repeat density (repeats/Mb) | recombination intensity (cM/Mb) | |

| D22S427 | 443 | 1.95 | 443 | 2.24 | 443 | 1.43 |

| D22S446 | 418 | 1.98 | 418 | 3.58 | 418 | 0.44 |

| D22S1174 | 655 | 1.32 | 655 | 1.98 | 680 | 0.59 |

| D22S1164 | 936 | 2.80 | 936 | 5.60 | – | – |

| D22S429 | 1224 | 4.51 | 1224 | 1.89 | 1224 | 7.09 |

| D22S1154 | 1524 | 3.31 | 1524 | 1.26 | 1524 | 6.54 |

| D22S1167 | 752 | 4.21 | 752 | 3.39 | 807 | 3.35 |

| D22S1144 | 1050 | 3.71 | 564 | 0.26 | – | – |

| D22S1163 | 547 | 0.13 | – | – | 547 | 0.26 |

| D22S275 | 723 | 4.31 | 723 | 4.39 | 723 | 4.23 |

| D22S273 | 562 | 1.15 | 568 | 0.76 | 562 | 0.75 |

| D22S1172 | 530 | 0.58 | – | – | 530 | 1.16 |

| D22S1158 | 627 | 1.37 | – | – | 627 | 3.18 |

| D22S1147 | 717 | 0.55 | – | – | 717 | 3.14 |

| D22S1152 | 553 | 2.23 | 553 | 2.64 | 553 | 0.63 |

| D22S424 | 1828 | 3.76 | 1828 | 4.52 | 735 | 0.25 |

| D22S278 | 1763 | 6.96 | 1763 | 14.1 | – | – |

| D22S1173 | 442 | 7.00 | 442 | 14.2 | – | – |

| D22S283 | 1348 | 8.09 | 1348 | 16.5 | – | – |

| D22S692 | 1909 | 3.39 | 1909 | 6.94 | – | – |

| D22S1045 | 400 | 1.79 | 400 | 3.68 | – | – |

| D22S1156 | 340 | 2.13 | 340 | 4.43 | – | – |

| D22S272 | 675 | 0.46 | 675 | 0.96 | – | – |

| D22S423 | 338 | 0.48 | 338 | 0.97 | – | – |

| D22S1157 | 627 | 0.40 | 627 | 0.83 | – | – |

| D22S1171 | 1250 | 3.36 | 1250 | 3.38 | 1250 | 3.07 |

| D22S1159 | 2032 | 3.50 | 2032 | 1.74 | 1754 | 4.48 |

| D22S1153 | 131 | 5.13 | 432 | 0.88 | – | – |

| D22S928 | 338 | 1.63 | – | – | 472 | 1.55 |

| D22S1149 | 480 | 0.80 | 480 | 0.99 | – | – |

| D22S1170 | 1655 | 6.45 | 1655 | 2.01 | 1655 | 11.2 |

| D22S922 | 2870 | 8.58 | 2870 | 8.58 | 2870 | 13.1 |

| D22S1169 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

The interval is defined between the marker in each row and the following marker. For example, the data in the first row refers to the D22S427–D22S446 interval. For the sex-specific data, some intervals contain no recombination data (no recombinants detected). The values in those cells have been averaged with adjacent intervals. For example, D22S273–D22S1152 is considered a single interval in the female-specific columns.

Table 2.

Correlations between Recombination Intensity and Microsatellite Density

| Microsatellite type | R2 | F1,30 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combineda | 0.23 | 8.80 | 0.0058 |

| Tetranucleotide | 0.08 | 2.66 | 0.11 |

| Trinucelotide | 0.06 | 1.76 | 0.19 |

| Dinucleotide (all) | 0.17 | 6.25 | 0.018 |

| Dinucleotide (non-GT) | 0.006 | 0.19 | 0.67 |

| Dinucleotide (GT only) | 0.36 | 17.01 | 0.00027 |

| Dinucleotide (GT, female) | 0.11 | 3.17b | 0.08 |

| Dinucleotide (GT, male) | 0.79 | 62.80b | 4 × 10−7 |

This is the combined density of di-, tri-, and tetranucleotides in repeat units per million base pairs.

Partitioning the data into male- and female-specific recombination results in loss of some data points. The reported F statistic values are F1,25 for female and F1,17 for male.

We detected a statistically significant positive relationship between recombination intensity and the total repeat density (all microsatellites combined). To determine whether the correlation is attributable to all microsatellites or only to a particular microsatellite type, we next subdivided the repeat density into three categories (i.e., di-, tri-, and tetranucleotide density) and repeated the regression analysis for each of the above variables. Table 2 shows that the contribution of trinucleotides and tetranucleotides is relatively minor and not statistically significant (P = 0.19 and P = 0.11, respectively). The only significant individual contribution is that of dinucleotide repeats (P = 0.018).

To test our initial hypothesis, that is that (GT)n microsatellites are associated with recombination, we further subdivided the dinucleotide microsatellites into GT and non-GT (i.e., GC, AT, and AG combined) types. The results of regression analyses using those two variables show a substantial contribution of GT repeats (P = 0.0003) and no contribution of other dinucleotides (P = 0.67).

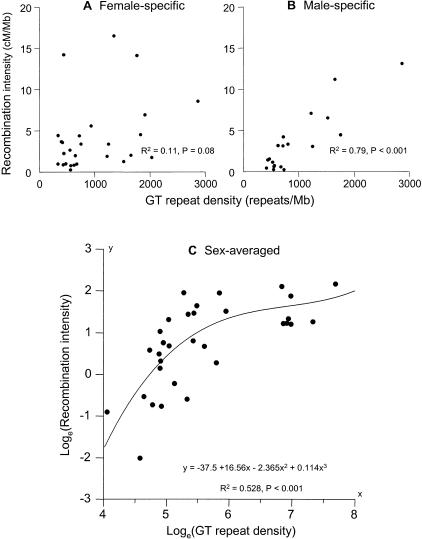

It is known that the patterns of meiotic recombination differ between males and females. Having shown the association between the sex-averaged recombination intensity and GT microsatellite density, we set out to determine whether the relationship is true for both sexes or is attributable to the association in one of the sexes but not the other. We used the male- and female-specific recombination intensities as dependent variables and performed the regression on GT repeat density (Fig. 1A,B). The analysis shows a strong positive relationship for male-specific recombination (R2 = 0.79, F1,17 = 62.8, P = 4 × 10−7) and a much weaker, borderline-significant relationship for the female-specific recombination (R2 = 0.11, F1,25 = 3.2, P = 0.08). The results suggest that the association is mostly male-specific, but this conclusion should be treated with caution, because partitioning the data between males and females results in a reduced number of meaningful intermarker intervals where recombinants have been detected and hence reduces the power of the analysis to detect association (see Methods section).

Figure 1.

Positive relationship between recombination intensity and GT repeat density. (A and B) Scatter-plots for females and males, respectively. The relationship is much more pronounced in males than in females and may in fact be mostly caused by the male-specific effect. (C) Sex-averaged results. The best fit for curvilinear regression was obtained by log-transforming the data and including second- and third-order polynomial terms. The line represents the regression curve given by the equation shown, where y = loge(recombination intensity) and x = loge(GT repeat density). The relationship is highly significant (R2 = 0.528, P = 8.7 × 10−5). The relationship is characterized by an initial rapid increase of recombination intensity with GT density, followed by a decline in the rate of increase. The recombination intensity possibly tends toward an asymptotic value for high repeat density levels. Note that the slight increase in the curve at high GT repeat density is most likely an artifact of limiting the regression to the first three terms.

Finally, we proceeded to characterize the mathematical relationship between recombination intensity and GT repeat density. For this part, we again used the sex-averaged recombination densities to extract the most information out of the data. We found that the association is improved when we use a higher cutoff value for reporting GT repeats (i.e., 22.5 repeat units as opposed to 12.5 units used initially). This suggests that it may be the longer repeats that contribute to the relationship, whereas the short repeats constitute simply background noise. We then determined that the best relationship is obtained when we log-transform the sex-averaged data in Table 1 and include second- and third-degree polynomials as independent variables in the regression (R2 = 0.528, F3,28 = 10.454, P = 8.7 × 10−5). The results are plotted in Figure 1C. The shape of the curve suggests that recombination intensity initially increases quickly with the density of repeats, but then tails off and might tend to an asymptotic value for high repeat density values. The value of R2 = 0.53 implies that 47% of variation in the rates of recombination (on the log scale) cannot be attributed to GT repeat density and suggests the existence of other recombinogenic factors.

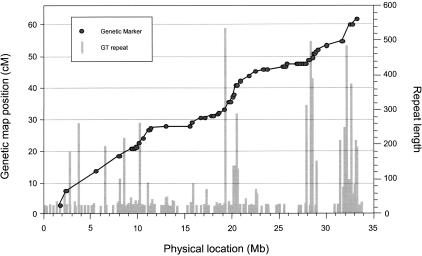

Figure 2 is a graphical representation of the statistical relationship described above. The physical distance from the centromeric end (in nucleotides) is plotted against the genetic map position for each marker. Recombination hot spots (as reported earlier by Dunham et al. 1999) correspond to regions with an elevated ratio of genetic to physical distance and are represented by an increased slope on the graph. Areas with relatively low recombination intensity (genetic/physical distance ratio) are represented by a lower than average gradient. We do not consider the subtelomeric region as a true recombination hot spot, because subtelomeres are generally characterized by increased recombination rates compared with the rest of the chromosome. (Hence, the most telomeric marker, D22S420, was excluded from the analysis above). We then plotted the number of repeats against the position of each repetitive sequence on chromosome 22 and overlaid the plot on that of genetic versus physical position of each marker. It can be seen that areas with high density of GT repeats and containing long GT repeats generally correspond to areas with increased recombination rates. Conversely, areas with relatively few GT repeats correspond to average or reduced recombination rates.

Figure 2.

Association of microsatellite GT repeats with recombination hot spots. The physical location and size of each GT repeat are superimposed on the plot of genetic map location (sex-averaged) against physical location for 59 markers on human chromosome 22. The height of each vertical bar represents repeat length. The slope of the line indicates relative recombination intensity within each intermarker region. Note that the locations of long GT repeats, as well as high concentrations of GT repeats, correspond to regions with elevated recombination rates. Conversely, regions with relatively few repeats have moderate or low recombination rates.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show an association between the GT microsatellite distribution and recombination frequency on human chromosome 22. Such association in itself cannot serve as a proof of causation, and it is possible that the observed relationship is entirely or partially attributable to unknown chromosomal factors that are correlated with GT repeats, such as properties of isochores where GT microsatellites may be preferentially found. Such regions may be particularly susceptible to double-stranded breaks or constitute extended tracts of open chromatin (Wahls 1998) responsible for the extended hot domains observed on chromosome 22. However, it is likely that the hot domains are composed of several localized hot spots, caused by local DNA sequence features such as tandem repeats. Several sources of experimental evidence implicate the involvement of GT microsatellites at various stages of the recombination process and suggest that tandem repeats may in fact be responsible for creating recombination hot spots.

Current models of recombination assume that the process is initiated by a double-strand chromosome break (Pittman and Schiementi 1998). Following the synapsis, branch migration extends the recombinant molecule until both recombinant junctions are resolved. Depending on the manner of resolution of the Holliday junctions, the released molecules may be true recombinants, or they may be nonrecombinant and contain a region of heteroduplex DNA.

Some recombinogenic factors may act early in initiating the process. These factors would most likely be chromosomal regions susceptible to double-strand breaks and enzymes associated with producing the breaks. In yeast, double-strand break sites are not uniformly distributed (Wahls 1998) and are likely to be responsible for the existence of some recombination hot spots.

Late-acting factors are probably involved in blocking branch migration or influencing the resolution of the Holliday junction. A chromosomal region that prevents further branch migration will be a hot spot for recombination, but only if the junction can be properly resolved in its vicinity. Thus, an interaction of at least two factors may be responsible for the existence of hot spots associated with the termination of the recombination process.

GT microsatellite repeats may be involved in the early stages of recombination. They have been shown to preferentially bind to the hsRad51 protein (Tracy et al. 1997). If the amounts of hsRad51 were limited during mitotic recombination, double-stranded breaks generated in the vicinity of GT repeats would be more likely to bind the available protein and be able to initiate recombination. Alternatively, in a model proposed by Wahls et al. (1990a), the presence of left-handed Z-DNA motif formed by long GT repeats may increase the length and hence stability of the paranemic joint formed during synapsis between two DNA molecules. Such stable synaptic joints would lead to increased frequency of crossing over in the proximity of Z-DNA regions.

Other experimental data suggests that GT repeats may be involved in termination of recombination. Biet et al. (1999) showed that GT microsatellites effectively block branch migration in vitro. If the same were true during mitotic recombination, such regions could result in recombination hot spots. This effect, however, would only be detectable by genetic cross-over events, if branch migration could proceed over extended distances of the order of megabases of DNA. Although the distance of branch migration is not known, we do not find this scenario very likely.

The recombinogenic potential of GT repeats in experimental systems is known to be influenced by neighboring genomic regions. Although Wahls et al. (1990a) found that GT repeats enhance recombination in tissue culture, Wahls and Moore (1990) showed that the binding of a viral antigen to a neighboring DNA sequence eliminates the recombinogenic effect. In addition, Sargent et al. (1996) found no influence of a similar GT microsatellite on recombination in hamster cell tissue culture. Hence, it is expected that factors such as neighboring sequence patterns and protein binding sites will modify the recombinogenic potential of GT repeats in the chromosomal context.

It is also likely that a hot spot may be located at some distance from the recombinogenic sequence. Wahls et al. (1990a) found that for recombination between small plasmid substrates, a hot spot occurs at up to 1.3 kb from the GT microsatellite. In a later review, Wahls (1998) suggests “tens of thousands of base pairs” as the distance over which the effect may extend, but the true limits of action of recombinogenic sequences are unknown and may be wider.

All of the above factors: several distinct underlying mechanisms of recombination enhancement, interaction between mechanisms, modifying factors, and possible action at a distance, make identification of recombinogenic factors more complicated. The results of our study support the role of GT repeats in promoting recombination but also suggest that other factors exist. The plot of recombination intensity against GT repeat density has a moderate coefficient of correlation (R2 = 0.53), suggesting that a large portion of the variation in recombination rates cannot be explained by GT repeat density alone and is probably attributable to other causes. The results also provide evidence that the association between recombination and GT repeats is stronger in males than in females and may in fact entirely be because of the male-specific effect. However, as explained in the Results section, the latter conclusion should be treated with some caution.

The increasing availability of contiguous sequence information will provide new opportunities for confirming the generality of predictions based on isolated observations. Our study of chromosome 22 shows that at least one putative recombinogenic sequence, a GT microsatellite repeat, may have a general effect in the context of the entire chromosome. As more of the human chromosomes, as well as the genomes of other organisms, are sequenced, it will be interesting to find out whether the effect is also genome-wide and true across genomes. It will also be interesting to investigate general effects of other putative recombinogenic sequences, such as minisatellite repeats, inverted repeats, and gene promoter regions. Our understanding of recombinogenic DNA motifs should have important applications in fields such as design of molecular vector systems and gene therapy.

METHODS

We used the sex-averaged and sex-specific genetic marker maps of chromosome 22 provided by the Marshfield Center for Medical Genetics (http://www.marshmed.org/genetics) with the exception of marker D22S922, the location of which is misrepresented in the Marshfield map and was corrected according to the original Centre d'Étude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) family data (http://www.cephb.fr/cephdb). Chromosome 22 DNA sequence (Dunham et al. 1999) was downloaded from the Sanger Center web site (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/HGP/Chr22). The locations of 59 markers along the chromosome 22 DNA sequence were determined by using BLAST to identify positive-strand PCR primer matches.

Microsatellite repeats were identified with the help of the Tandem Repeat Finder (Benson 1999). The program uses a criterion based on the alignment score (Karlin and Altschul 1990) to detect repeats of arbitrary length and degree of imperfect duplication. We used two cutoff criteria. In the preliminary analysis, to show association between GT repeats and recombination we used a cutoff score of 50, which allows detection of all perfect dinucleotide repeats of length 12.5 units, trinucleotide repeats of 8.3 units, and tetranucleotide repeats of ≥ 6.3 repeated units. Longer repeats are allowed a certain percentage of mismatches and deletions according to the (2, 7, 7) alignment criterion (+ 2 points for every match, − 7 points for each mismatch and deletion). In the analysis aimed at characterizing the relationship between recombination and GT repeat density, we found that a more stringent cutoff criterion of 90 (i.e., only detecting perfect GT repeats of length ≥ 22.5) improved the statistical significance of the association. The higher cutoff choice was partly motivated by the fact that GT repeats of 30 units are known to enhance recombination (Treco and Arnheim 1986). Setting the cutoff at a slightly lower level allows the detection of slightly imperfect repeats of similar length while rejecting considerably shorter repeats, which do not form unusual structures such as Z-DNA and are unlikely to influence recombination.

The regression analysis was performed by considering only regions where recombinants have been detected and which contained microsatellite repeats. That is, intermarker segments with no recombinants were averaged with the adjacent centromeric segments. This was necessary, because in the absence of such averaging, small segments containing no information cluster at the origin whereas larger segments tend to cluster around the mean coordinates of (recombination intensity, repeat density), leading to a bimodal distribution and a false-positive regression. The regression based on averaging is more conservative, but both types of analysis lead to a significant result (data for the nonaveraged analysis not shown). The most telomeric marker, D22S420, was excluded from the analysis because of the position-specific enhancement of recombination rates in the subtelomeric regions. The presented regression analysis ignores the presence of some gaps in the published DNA sequence. However, an analysis in which we have excluded the regions containing gaps is still highly significant (P < 0.001).

It should be noted that in human populations the lengths of nucleotide repeats at each given chromosomal position are not constant among individuals. Such polymorphisms may introduce a bias when only one sequenced individual is used to test for a general correlation between recombination intensity and repeat density. However, microsatellite sizes (at a given chromosomal location) are roughly normally distributed about their mean value (see http://www.cephb.fr/cephdb). The standard deviation of the distribution is usually considerably smaller than the mean repeat length, with extreme alleles being very rare. Assuming that each individual microsatellite evolves independently, and given that each intermarker interval contains many microsatellites (true for this data set), the average microsatellite density within each interval for the individual whose DNA was sequenced should constitute a valid estimate of mean microsatellite density within the same interval for an entire population.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wentian Li for help and ideas regarding DNA sequence analysis, and two anonymous reviewers for suggestions on improving the paper. This work was supported by grant HG00008 from the National Human Genome Research Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL majewski@complex.rockefeller.edu; FAX (212) 327-7996.

REFERENCES

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biet E, Sun J-S, Dutreix M. Conserved sequence preference in DNA binding among recombination proteins: An effect of ssDNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:596–600. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Murray JC, Sheffield VC, White RL, Weber JL. Comprehensive human genetic maps: Individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:861–869. doi: 10.1086/302011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dausset J, Cann H, Cohen D, Lathrop M, Lalouel JM, White R. Centre d'étude du polymorphisme humain (CEPH): Collaborative genetic mapping of the human genome. Genomics. 1990;6:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90491-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dib C, Faure S, Fizames C, Samson D, Drouot N, Vignal A, Millasseau P, Marc S, Hazan J, Seboun E, et al. A comprehensive genetic map of the human genome based on 5264 microsatellites. Nature. 1996;380:152–154. doi: 10.1038/380152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham I, Shimizu N, Roe BA, Chissoe S, Hunt AR, Collins JE, Bruskiewich R, Beare DM, Clamp M, Smink LJ, et al. The DNA sequence of human chromosome 22. Nature. 1999;402:489–495. doi: 10.1038/990031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutreix M. (GT)n repetitive tracts affect several stages of RecA-promoted recombination. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:105–113. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman L, Steen M, Sundvall M, Pettersson U. A rapidly evolving region in the immunoglobulin heavy chain loci of rat and mouse: Postulated role of (dC-dA)n.(dG-dT)n sequences. Gene. 1988;68:93–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin S, Altschul SF. Methods for assessing the statistical significance of molecular sequence features by using general scoring schemes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1990;87:2264–2268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori JA, Strauss E, Minard K, Hood L. Molecular analysis of the hotspot of recombination in the murine major histocompatibility complex. Science. 1986;234:173–179. doi: 10.1126/science.3018929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Fann CS, Ott J. Low-order polynomial trends of female-to-male map distance ratios along human chromosomes. Hum Hered. 1998;48:266–270. doi: 10.1159/000022814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Buard J, Neil DL, Yeremian E, Tamaki K, Hollies C, Jeffreys A. Comparative sequence analysis of human minisatellites showing meiotic repeat instabillity. Genome Res. 1999;9:130–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman DL, Schiementi JC. Recombination in the mammalian germ line. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1998;37:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent RG, Mrrihew RV, Nairn R, Adair G, Meuth M, Wilson JH. The influence of a (GT)29 microsatellite sequence on homologous recombination in the hamster adenine phosphoribosyltransferase gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:746–753. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.4.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah R, Bennett RJ, West SC. Genetic recombination in E. coli: RuvC protein cleaves Holliday junctions at resolution hotspots in vitro. Cell. 1994;79:853–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GR, Kunes SM, Schultz DW, Taylor A, Triman KL. Structure of chi hotspots of generalized recombination. Cell. 1981;24:429–436. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy RB, Baumohl JK, Kowalczykowski SC. The preference for GT-rich DNA by the yeast Rad51 protein defines a set of universal pairing sequences. Genes & Dev. 1997;24:3423–3431. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treco D, Arnheim N. The evolutionarily conserved repetitive sequence d(TG.AC) promotes reciprocal exchange and generates unusual recombinant tetrads during yeast meiosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3934–3947. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahls WP, Moore PD. Homologous recombination enhancement conferred by the Z-DNA motif d(TG)30 is abrogated by simian virus 40 T antigen binding to adjacent DNA sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:794–800. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahls WP, Wallace LJ, Moore PD. The Z-DNA motif d(TG)30 promotes reception of information during gene conversion events while stimulating homologous recombination in human cells in culture. Mol Cell Biol. 1990a;10:785–793. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Hypervariable minisatellite DNA is a hotspot for homologous recombination in human cells. Cell. 1990b;60:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90719-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahls WP. Meiotic recombination hotspots: Shaping the genome and insights into hypervariable minisatellite DNA change. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1998;37:37–75. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60171-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintle RF, Nygaard TG, Herbrick JA, Kvaloy K, Cox DW. Genetic polymorphism and recombination in the subtelomeric region of chromosome 14q. Genomics. 1998;40:409–414. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]