Abstract

Computational analysis of sequences of proteins involved in translation initiation in eukaryotes reveals a number of specific domains that are not represented in bacteria or archaea. Most of these eukaryote-specific domains are known or predicted to possess an α-helical structure, which suggests that such domains are easier to invent in the course of evolution than are domains of other structural classes. A previously undetected, conserved region predicted to form an α-helical domain is delineated in the initiation factor eIF4G, in Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay 2 protein (NMD2/UPF2), in the nuclear cap-binding CBP80, and in other, poorly characterized proteins, which is named the NIC (NMD2, eIF4G, CBP80) domain. Biochemical and mutagenesis data on NIC-containing proteins indicate that this predicted domain is one of the central adapters in the regulation of mRNA processing, translation, and degradation. It is demonstrated that, in the course of eukaryotic evolution, initiation factor eIF4G, of which NIC is the core, conserved portion, has accreted several additional, distinct predicted domains such as MI (MA-3 and eIF4G ) and W2, which probably was accompanied by acquisition of new regulatory interactions.

Initiation of translation is a multistep process that includes the formation of a ternary complex of initiator tRNAfMet, GTP, and a GTPase initiation factor. This is followed by the association of this complex with the ribosome and mRNA, which is accompanied by GTP hydrolysis. The principal stages of initiation are the same in all cells (Dever 1999). In spite of this general functional similarity, however, there is little direct correspondence between the translation initiation factors in archaea/eukaryotes and in bacteria. Archaea and eukaryotes share several homologous components of their initiation complex that have no counterparts in bacteria, and in some cases, when homologs are present, they participate in related but distinct functions (Makarova et al. 1999).

The intricate molecular mechanisms of translation initiation in eukaryotes and the proteins involved in this process have been studied in considerable detail (Table 1). The aspect that is understood best is the GTPase cycle, which involves the trimeric GTPase eIF2, its GDP/GTP exchange factor—the multisubunit factor eIF2B, and the GTPase-activating protein eIF5 (Dever 1999). GTP hydrolysis is required for the recognition of the start codon, which also involves eIF1 (Sui1) and eIF1A (Pestova et al. 1998). The cap that is present at the 5′-end of most eukaryotic mRNAs is recognized by eIF4E, which, in turn, binds to the large eIF4G protein, which then recruits the helicase eIF4A. This RNA helicase unwinds the secondary structure around the cap and allows scanning for the start codon (Dever 1999; Pestova and Hellen 1999). The giant, multi-subunit complex eIF3 interacts with GTPase-activating proteins eIF5 and eIF1 (Asano et al. 1998; Asano et al. 1999) and also with the eIF4 complex (Lamphear et al. 1995). These interactions of eIF3, respectively, are believed to recruit the Met-tRNA and mRNA to the ribosome. In the cap-independent translation initiation that is typical of picornaviruses, eIF4G directly binds the internal initiation sites and recruits the ribosome (Dever 1999; Pestova and Hellen 1999). Although a number of details in these processes are well understood, certain key questions remain unanswered, such as the principal sequence and structural determinants of specific protein–protein and protein–RNA interactions. These include the interactions between different initiation factors, for example, eIF3 and eIF4G, and their interactions with mRNA.

Table 1.

Phyletic Distribution and Conserved Domains in Components of the Eukaryotic Translation Initiation System

| Protein/GI numbera | Phyletic distributionb | Domain organizationc | Structural class of conserved domain | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eIF1 (SUI1) 4240113 | EAB [Bacteria = Ec, Hi, Ssp] | Sui1 domain | α + β | Probably horizontally transferred into bacteria |

| eIF1A (eIF4C) 626955 | EAB | OB-fold domain | β | Bacterial IF1 ortholog |

| IF2 (eIF5B) 1723187 | EAB | Multidomain GTPase | α + β | Ortholog of bacterial IF2, appears to be necessary for joining of the 2 ribosomal subunits in both eukaryotes and bacteria |

| eIF2α 124203 | EA | S1 RNA-binding domain | β | |

| eIF2β 4503505 | EA | Zinc ribbon | β | A similar Zn-ribbon found in eIF5 |

| eIF2γ 3790165 | EA(B) | GTPase (Zn-ribbon insertion) | α + β | The most similar bacterial homologs are elongation factors SelB/EF-TU |

| eIF2Bα 2494303 eIF2Bβ 2661031 eIF2Bδ 417036 | EAB [Bacteria = Ssp, Bs, Tma, Rhoru] | α-helical DEF domain for the eIF2 GTPase | α | Probably horizontally transferred into bacteria |

| eIF2Bγ 2506383 | E(AB) | Nucleotidyltransferase + I-patch repeats | α + β | Several bacteria encode homologous proteins that are unlikely to function in translation |

| eIF2Bɛ 2408098 | E(AB) | Nucleotidyltransferase + I-patch repeats + W2 | α + β and α | Several bacteria encode homologous proteins that are unlikely to function in translation |

| eIF2C 3253159 | EAB [Bacteria = Aae] | Argonaute homolog | α + β | Apparent horizontal transfer from archaea to Aquifex. Expansion of this family in C. elegans |

| eIF3-p39 (TIF34p) 6323795 | E | WD40-β-propeller | β | Probable mRNA-binding subunit |

| eIF3-p40 2351380 | E(AB) | JAB/PAD domain | α + β | Related to/part of the signalosome complex |

| eIF3-p44 (TIF35p) 6320637 | E | C-terminal RRM | α + β | |

| eIF3-p47 2055431 | E(AB) | JAB/PAD domain | α + β | Related to/part of the signalosome complex. Missing in S. cerevisiae |

| eIF3-p48 2351382 | E | PINT domain | α | Related to/part of the signalosome complex. Missing in S. cerevisiae |

| eIF3-p66 2351378 | E | ? | ? | Related to/part of the signalosome complex. Missing in S. cerevisiae |

| eIF3-p110 (NIP1) 1718197 | E | PINT domain | α | Related to/part of the signalosome complex |

| eIF3-p116 (PRT1p) 3123230 | E | RRM + β-propeller | α + β and β | Probable mRNA-binding subunit |

| eIF3-p150 | E | ? | α | |

| eIF3-p162 (TIF32p) 2580607 | E | ? | α | |

| eIF4A 6322912 | E(AB) | Superfamily II helicase | α + β | |

| eIF4B 464817 | E | Two RRM domains | α + β | |

| eIF4E 1352435 | E | Unique α/β fold | α + β | 25 kD subunit of eIF4F |

| eIF4G 3941724 | E | NIC domain NIC + MI NIC + MI + W2 | α | Other domains added to the NIC domain in certain eukaryotic lineages. 150kD subunit of eIF4F |

| eIF4H 2914759 | E | RRM | α + β | Closely related to eIF2B, appears to be vertebrate-specfic |

| eIF5 1708419 | E | Zn ribbon + W2 | β and α | The Zn-ribbon is closely related to the ribbon in eIF2 β subunit. A related ribbon is seen in Archaea as a stand-alone protein |

| eIF5A (eIF4D) 124229 | EAB | OB fold protein | β | The bacterial ortholog is EF-P. Eukaryotic eIF5A contains a lysine to hypusine modification that is necessary for function. |

| eIF6 6325273 | EA | Duplication of a unique domain | ? |

For each factor, a Gene Identification (GI) number of a representative eukaryotic sequence is given to ensure unambiguous identification in databases

E—eukaryotes, A—archaea, B—bacteria. In cases when bacteria and/or archaea encoded homologs of the respective eukaryotic factor that do not seem to be true orthologs, B and/or A is indicated in parentheses. When the distribution of the orthologs of the respective eukaryotic factor in bacteria is sporadic, the species encoding it are indicated in square brackets. Species abbreviations: Aae—Aquifex aeolicus, BS—Bacillus subtilis, Ec—Escherichia coli, Hi—Haemophilus influenzae, Rhoru—Rhospirillum rubrum, Ssp—Synechocystis sp, Tma—Thermotoga maritima.

A question mark indicates absence of distinct, recognizable domains.

One approach to improving our understanding of the properties of these molecules is the computational dissection of different translation components into (predicted) conserved domains and the mapping of the functions to them. The development of sensitive profile search methods and robust means of statistical evaluation of search results have made this approach effective (Altschul et al. 1997; Aravind and Koonin 1999a). The recent computational analyses of the translation system have resulted in the identification of several distinct, conserved nucleic-acid-binding domains in ribosomal proteins, eIF1, rRNA/tRNA-modifying enzymes, and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, as well as conserved enzymatic and interaction domains in eIF3, eIF2Bε, and eIF2Bγ (Koonin 1995; Aravind and Ponting 1998; Aravind and Koonin 1999b; Makarova et al. 1999; Wolf et al. 1999). Some of these predictions have been experimentally confirmed, supporting the utility of the computational approach in understanding the functions and evolution of the conserved components of the translation machinery (Asano et al. 1999; Korber et al. 1999).

Here we present an analysis of the conserved domains and phyletic distribution of all known eukaryotic translation initiation factors. As part of this analysis, we predict a conserved α-helical domain in eIF4G that is also present in a number of other proteins such as Nonsense-mediated decay protein 2, the nuclear cap-binding complex 80-kD subunit, and nucampholin. We propose that a common domain had been recruited early in eukaryotic evolution for the regulation of translation initiation, mRNA degradation, and splicing. We also observe that eIF4G has undergone domain accretion in the course of eukaryotic evolution, with the core domain being combined with other domains in plants and animals. We show that almost all eukaryote-specific components of the translation initiation complex belong to protein families whose phyletic distribution is limited to eukaryotes, and most of them are known or predicted to possess an α-helical structure. Thus it appears that one of the major innovations at the onset of the evolution of eukaryotes involved the derivation of several new components of the translation initiation machinery.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Phyletic Distribution and Conserved Domains of Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factors

We sought to investigate the origins of eukaryote-specific components of the translation initiation system by analyzing their phyletic distribution and detecting all the conserved (predicted) globular domains present in them. Table 1 shows the currently recognized components of the eukaryotic translation initiation system, their phyletic distribution, and the detectable conserved domains. The most prominent general feature of this distribution is that several of the components are shared between eukarya and archaea, but very few have counterparts in bacteria. However, three initiation factors, namely, IF2, eIF1A, and eIF5a, are universal and appear to have retained at least part of their respective functions from the common ancestor of all life forms. IF2 is a multidomain GTPase involved in the delivery of the initiator Met-tRNAfMet to the ribosome and the joining of the two ribosomal subunits in the bacterial translation initiation process (Laalami et al. 1991, 1996). In archaea and eukaryotes, it was believed to function similarly to the bacterial IF2, in delivering the Met-tRNAMet to the ribosome (Choi et al. 1998; Lee et al. 1999). Recently, however, it has been shown that eukaryotic IF2 is identical to eIF5B and mediates joining of the large and small ribosomal subunits rather than recruiting Met-tRNAMet (Pestova et al. 2000). The bacterial ortholog of eIF1A is the initiation factor IF1; these factors contain a characteristic, conserved nucleic-acid-binding oligomer-binding (OB)-fold domain that is likely to be involved in initiator codon recognition in all translation systems (Sette et al. 1997; Battiste et al. 2000). eIF5A and its bacterial ortholog EF-P also are OB-fold proteins (Kim et al. 1998; Peat et al. 1998) that might function similarly in all three domains of life in the formation of the first peptide bond (Aoki et al. 1997). In the case of eIF1 and eIF2Bα/β/δ, which are conserved in archaea and eukaryotes, orthologs are sporadically represented in subsets of bacteria, with a distinct relationship to the archaeal counterparts (Table 1). Horizontal transfer of the respective genes from archaea to bacteria seems to be a plausible scenario for their evolution, but it is not clear whether or not the bacterial orthologs of these archaeal/eukaryotic factors retain the same function in translation.

A significant number of translation initiation factors are shared by archaea and eukaryotes, to the exclusion of bacteria (Table 1). These include the GTPase eIF2 and the exchange factors involved in the GTPase cycle as well as less studied proteins such as eIF2C and eIF6. These factors are likely to represent the core initiation system that was present in the common ancestor of archaea and eukaryotes. A protein related to the zinc-ribbon domain of eIF5 and eIF2β is highly conserved in archaea, but its function in translation, if any, is unclear (Makarova et al. 1999). The remaining components appear to be specific to eukaryotes and include the large complexes eIF3 and eIF4 (Table 1). The recognizable conserved domains found in several of these proteins are typically found only in eukaryotes. In eIF4, which is predominantly involved in recognizing the eukaryote-specific cap structure in mRNAs, the only ancient conserved domain is the superfamily II RNA helicase domain of eIF4A. This helicase has archaeal and bacterial homologs, but none of these appear to be true orthologs, even if some of them might play analogous roles in translation initiation. Structure determination has shown that eIF4E, which is directly involved in cap-binding, possesses a novel α/β fold that has no homologs, detectable by sequence or structural comparison, outside the eukaryotes (Marcotrigiano et al. 1997; Matsuo et al. 1997).

The eIF3 complex contains several characteristic eukaryotic domains such as RRM, WD40, and related β-propeller domains, PINT, and JAB/PAD domains (Aravind and Ponting 1998; Hofmann and Bucher 1998) (Table 1). Some of these domains have been detected in one or more bacterial species (Table 1), but in the majority of cases, the provenance of the respective genes could be attributed to horizontal transfer from the eukaryotes (Ponting et al. 1999). We sought to expand this list of conserved domains detected in eukaryote-specific initiation factors in order to obtain additional information on their functions and evolution. One of the principal targets of this analysis was eIF4G, a large protein that is involved in multiple interactions with eIF4A, eIF4E, and possibly eIF3, as well as mRNA, and is required for both cap-dependent and cap-independent initiation (Dever 1999; Pestova and Hellen 1999). A short peptide enriched in aromatic and hydrophobic residues has been shown to be responsible for the interaction of eIF4G with eIF4E (Marcotrigiano et al. 1999), but the nature of other conserved domains in this protein has so far remained obscure.

NIC—A Common Domain in eIF4G and Other Cap-associated Proteins

A sequence comparison of eIF4G and related proteins, such as DAP-5/NAT1/p97 and PAIP1, from different eukaryotes reveals a conserved central region that is predicted to adopt a predominantly α-helical structure (Levy-Strumpf et al. 1997; Craig et al. 1998). To identify the approximate limits of the globular domain contained in this region, the sequences were filtered for low complexity using the SEG program (parameters: window = 45; initiation complexity = 3.4, extension complexity = 3.75). It has been shown that regions of high complexity roughly correspond to globular domains (Wootton and Federhen 1996). The sequence of the predicted globular domain was used as a query in an iterative PSI-BLAST search, which resulted in the detection of similar sequences, with statistically significant e-values (typically, E < 0.001), in the Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay 2 protein (NMD2/UPF2), the nuclear cap-binding protein 80-kD subunit (CBP80), and other, less studied proteins such as nucampholin encoded by the let-858 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans, YelA from Dictyostelium discoideum, and SGD1p from yeast. This set of proteins was consistently retrieved form the NR database using other queries such as CBP80 and NMD2. In addition, searches started with the conserved sequence from CBP80 helped in detecting divergent versions of this domain in the yeast protein GCR3 and its ortholog from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Given the presence of this region of similarity in a large set of diverse proteins, we predict that it defines a new conserved domain and accordingly named it NIC after NMD2, eIF4G, CBP80.

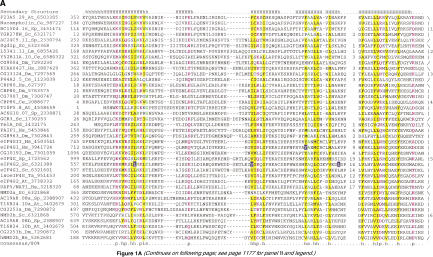

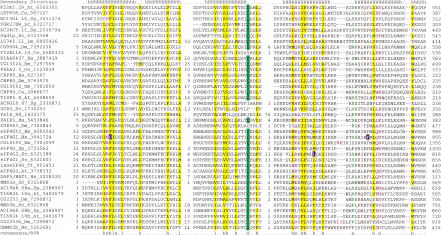

NIC is a large region that consists of approximately 240 amino acid residues (Fig. 1A). The boundaries of the predicted domain were determined with considerable precision using NMD2, which contains a tandem duplication of NIC region, and CBP80, in which NIC occurs at the extreme N-terminus. Secondary structure predictions indicate that the NIC domain assumes an all α-helical fold that contains inserts rich in charged residues and is predicted to be exposed (Fig. 1A). The conservation pattern of the predicted NIC domain is centered around hydrophobic and polar residues that are likely to be important in maintaining the α-helices. A notable feature is a conserved glycine that is present in the carboxyl-terminal region of the domain and could determine a crucial turn in the three-dimensional structure (Figure 1A). This conservation pattern, together with the predicted helical structure of the NIC domain, suggests that it could participate in protein–protein interactions or nucleic-acid-binding. A match to the RRM signature has been reported in the region of the eIF4G protein (Goyer et al. 1993) where we predict the NIC domain; we were unable to find statistical support for the presence of an RRM domain and consider it highly improbable, given that the NIC domain is predicted to possess an all α-fold, whereas the RRM contains a prominent β-sheet.

Figure 1.

(A) (See pages 1175 and 1176.) Multiple sequence alignment of the predicted NIC domain. (B) Multiple sequence alignment of the predicted MI domain. The proteins are designated by their name, followed by the species abbreviation and GenBank gene identifier. The numbers on either side of the alignment represent the position of the first and last residue of the respective domain in each protein. A consensus secondary structure predicted using the PSIPRED and PHD programs is shown above the alignment. The coloring is based on the 80% consensus in part A and the 85% consensus in part B: h—hydrophobic residues / l—aliphatic residues shaded yellow (YFWLIVMA), c—charged residues colored magenta, p—polar residues colored purple (STQNEDRKH), s—small residues colored green (SAGTVPNHD), t—tiny residues shaded green (GAS), and b—big residues shaded gray (KREQWFYLMI). The point mutations in the human eIF4G1 and yeast eIF4G2 that affect translation are high-lighted in blue in the NIC domain alignment. In the case of the NIC domain alignment 6 distinct families are delineated by brackets to the right of the alignment panel 1. These families are (1) Nucampholin-like, (2) SGD1p-like, (3) KIAA0427-like, (4) CBP80-like, (5) eIF4G-like, and (6) NMD2-like. The species abbreviations are: At— Arabidopsis thaliana, Ce— Caenorhabditis elegans, Dm— Drosophila melanogaster, Mm— Mus musculus, Hs— Homo sapiens, Sc— Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Sp— Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Ta— Triticum aestivum, Pf—Plasmodium falciparum, and Lm—Leishmania major.

All the characterized proteins containing the predicted NIC domain function either in translation or in mRNA metabolism. CBP80 (Izaurralde et al. 1994) and eIF4G (Dever 1999; Morino et al. 2000) are associated with the 5′-cap of mRNA in the nucleus and in the course of translation, respectively. Neither of these proteins, however, directly binds cap—a function that is mediated by CBP20 in the nuclear cap-binding complex (Izaurralde et al. 1994; Fortes et al. 1999) and by eIF4E in the cytoplasmic translation complex (Quiocho et al. 2000). NMD2/UPF2 is involved in the degradation of mRNAs when translation initiation is inhibited or when they contain premature nonsense codons (Cui et al. 1995). Nucampholin and related NIC-domain proteins have not been functionally characterized; however, these proteins contain highly charged serine-arginine-rich segments at their extreme carboxyl termini (Fig. 2), which are typical of several RNA-binding proteins (Blencowe et al. 1999), suggesting a role in RNA metabolism similar to that of other NIC-containing proteins.

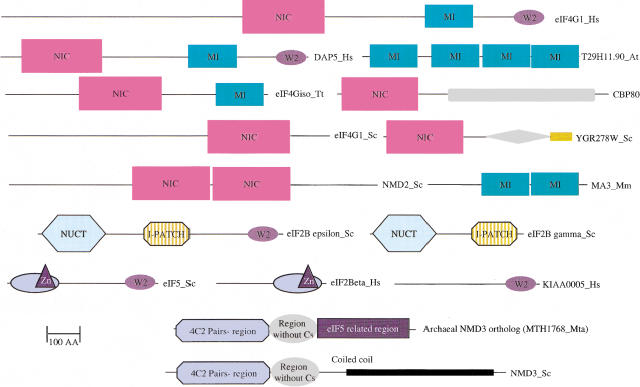

Figure 2.

Domain organization of selected eukaryotic translation initiation factors and their homologs. The individual domains are drawn approximately to scale and are labeled by the acronyms that are indicated in the text. Zn in eIF2β and eIF5 indicates a zinc-ribbon. The additional unlabeled regions in CBP80 and YGR278w represent predicted globular domains that are not found in other proteins. The orange bar at the carboxyl terminus of YGR278w shows the RS repeat segment that is also found in several proteins participating in RNA metabolism. I-patch is an isoleucine-rich hexapeptide repeat domain, and NUCT is a nucleotidyl transferase domain of the sugar-nucleotide diphosphate-transferase family (Koonin 1999).

Evidence from different deletion and mutagenesis analysis of eIF4G points to the functional importance of the predicted NIC domain. These studies on yeast (Dominguez et al. 1999; Neff and Sachs 1999) and human eIF4G (Imataka and Sonenberg 1997; Morino et al. 2000) and circumstantial evidence for the plant counterpart (Kim et al. 1999) suggest that a fragment of eIF4G that entirely encompasses the NIC region is necessary for the interaction with the helicase eIF4A. Point mutations in the predicted NIC domain of yeast eIF4G2 (Neff and Sachs 1999) and human eIF4G1 (Morino et al. 2000) disrupt the interaction with eIF4A. Similarly, PAIP1, a vertebrate protein whose only region of similarity with eIF4G is centered around the predicted NIC domain, binds eIF4A and helps in linking the 5′–end of mRNA with the 3′-polyA tail (Craig et al. 1998). Furthermore, in the case of the vertebrate eIF4G, there is evidence that the region containing the NIC domain is also necessary for eIF3-binding (Lamphear et al. 1995; Morino et al. 2000). A fragment of eIF4G1 that encompasses only the eIF4E-binding site and the predicted NIC domain can drive cap-dependent translation along with eIF4E (Morino et al. 2000). When fused to a heterologous RNA-binding domain, the NIC-containing fragment of eIF4G circumvents the need for the cap or eIF4E in translation and promotes translation initiation from the binding site of the RNA-binding domain (De Gregorio et al. 1999). These observations suggest a protein–protein-interaction-dependent adapter role for the NIC domain.

Mutations in the highly conserved Y776 and F862 and the moderately conserved F938 in the human eIF4G1 (highlighted in blue in Fig. 1A) abrogate eIF4A binding and translation initiation (Morino et al. 2000). Similarly, several temperature-sensitive mutations in the yeast eIF4G2 that are suppressed by the overexpression of eIF4A also map to well-conserved hydrophobic residues (Fig. 2) (Neff and Sachs 1999). The conservation of these residues in most of the diverse predicted NIC domains (Fig. 1A) suggests a common structural basis for their protein–protein interactions, not only in translation initiation but also in other contexts. Additionally, the region of eIF4G encompassing the predicted NIC domain has been reported to bind RNA in the case of plant eIF4G, but the contribution of the NIC domain to this activity is unclear because deletions N-terminal of the predicted NIC domain result in loss of RNA binding (Kim et al. 1999). Based on all these observations and the predicted structural features of the NIC domain, we conclude that it is likely to be the primary adapter domain of eIF4G involved in multiple, specific protein–protein interactions within the initiation complex.

This interpretation has interesting implications for the function of the NMD2/UPF2 protein, which has been shown to interact physically with another protein in the RNA degradation pathway, UPF1 (an RNA helicase), via a region located carboxyl-terminally of the two predicted NIC domains (He et al. 1997). In contrast, the region containing the predicted NIC domains inhibits the NMD2–UPF1 interaction, but in part mediates the interaction of NMD2 with UPF3, another protein in the degradation pathway (He et al. 1997). This suggests a regulatory function for the NIC domain, mediated by specific protein–protein interactions. Mutations in the eIF3 subunit PRT1(p116) result in mRNA degradation via the NMD pathway (Barnes 1998). Together with the presence of predicted NIC domains in both eIF4G and NMD2, this suggests that NMD2 could interact with the translation initiation complex similarly to eIF4G and sense the state of translation of a message prior to its degradation. In this context, it is notable that NMD3, another component of the NMD pathway that is highly conserved in archaea and eukarya, also plays an essential role in translation at the stage of 60S subunit assembly (Belk et al. 1999; Ho and Johnson 1999). The archaeal orthologs of NMD3 contain an additional carboxyl-terminal region that is homologous to eIF5A (Fig. 2), which suggests the possibility of functional cooperation between eIF5A and NMD3 in eukaryotes. More generally, these findings indicate that the NMD system of mRNA degradation might have evolved as an extension of the ancestral translation initiation system.

The presence of predicted NIC domains in the nuclear cap-binding protein CBP80 is of particular interest because it suggests a common evolutionary origin for the nuclear and cytoplasmic cap-binding complexes. Early in eukaryotic evolution, an ancestral protein containing the NIC domain could have served as an adapter in both the nuclear and the cytoplasmic contexts, with subsequent divergence and evolution of distinct binding specificities. The predicted NIC domain in CBP80 is likely to function as an adapter in the interactions of the splicing complex with the cap, as supported by genetic evidence (Izaurralde et al. 1994; Fortes et al. 1999). The other family of NIC-domain proteins that is conserved throughout the eukaryotic crown group is typified by the products of the C. elegans let-858 gene. Mutations in this gene that encodes the nuclear protein nucampholin are lethal, with a phenotype typical of treatments that completely block gene expression (Kelly et al. 1997). Together with the presence of SR-repeats, this indicates that, similarly to CBP80, nucampholin could also function as an adapter affecting nuclear pre-mRNA processing or transport. The single predicted NIC domains found in yeast SGD1p, human DAP-5/NAT-1/p97, and YelA from Dictyostelium are likely to perform a regulatory function. DAP-5/NAT-1/p97 has been shown to suppress both cap-dependent and cap-independent translation and is activated during apoptosis by caspase cleavage, which results in a fragment that contains the NIC domain (Imataka et al. 1997; Levy-Strumpf et al. 1997; Yamanaka et al. 1997; Henis-Korenblit et al. 2000). This protein seems to function by preventing the normal interactions of eIF4A/eIF3 in initiation by forming nonfunctional complexes with either of these initiation factors (Henis-Korenblit et al. 2000). Similarly, YelA appears to repress sporulation in Dictyostelium, which could be enacted through selective inhibition of translation of genes whose products normally promote sporulation (Osherov et al. 1997). Some of the functionally uncharacterized proteins containing predicted NIC domains, for example, yeast Sgd1p and its orthologs, are also conserved in all crown group eukaryotes as well as in the early branching eukaryote Leishmania major (Fig. 1A). These proteins might define additional, so far undetected, conserved regulatory pathways affecting mRNA stability, pre-mRNA processing, or translation.

Other Eukaryote-specific Domains and Prediction of New Translation Regulators

In addition to the predicted NIC domain, there are several other conserved domains present in eukaryotic translation factors and in certain other proteins that potentially could function in translation initiation or mRNA metabolism. In an earlier study, we have described proteins conserved throughout eukarya that contain the SUI1 (eIF1) domain and are predicted to play a role in translation (Aravind and Koonin 1999b). Another conserved region is located to the carboxyl terminus of the predicted NIC domain in plant and animal eIF4G and DAP-5/NAT1/p97, but not in PAIP1 or yeast eIF4G (Figs. 1B, 2). This region, predicted to form an α-helical domain (Fig. 1B), was also found in two copies in the animal protein MA-3 (Pdcd4) that is induced during programmed cell death and inhibits neoplastic transformation (Shibahara et al. 1995; Cmarik et al. 1999). In this protein, the predicted domain shared with eIF4G is the only recognizable conserved feature (Fig. 2). Accordingly, we named this predicted domain MI after MA-3 and eIF4G. Experimental evidence suggests that in eIF4G the MI domain could form a second eIF4A-binding site (Imataka and Sonenberg 1997). A group of uncharacterized plant proteins contain four tandem-repeated predicted MI domains (Figs. 1B, 2). These multi-MI domain proteins could act as translation regulators analogous to DAP-5/NAT1/p97, by blocking the interaction of eIF4G with the rest of the translation initiation complex. A protein containing a single predicted MI domain was found in Plasmodium falciparum, suggesting an ancient origin for this predicted domain in eukaryotes, followed by its loss in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae lineage (Fig. 1B). This correlates with the loss of several subunits of the eIF3 complex in S. cerevisiae (Table 1) and indicates that the MI domain may have a role in mediating and regulating some of the interactions of eIF4G with eIF3.

The extreme carboxyl termini of the animal eIF4G and DAP-5/NAT1/p97 contain a small but notably conserved domain shared with the eIF2Bε subunit and eIF5 (Koonin 1995). This domain contains two conserved tryptophans (hence named W2) and participates in the interaction of the eIF2Bε subunit and eIF5 with the eIF2β subunit (Asano et al. 1999) as well as in the interaction of animal eIF4G with the protein kinase MNK1 (Morino et al. 2000). Iterative database searches with the W2 domain detected a protein containing this domain as the only identifiable feature that is conserved in plants and animals (KIAA0005 [Human, GI: 286001]; CG2922 [Drosophila, GI: 7296717], T23K8.13 [Plant, GI: 4646206[, Fig. 2). This protein is predicted to act as a potential translation regulator that could modulate interactions of eIF2Bε, eIF5, and eIF4G with other proteins such as eIF2β and MNK1. Two distinct pairs of initiation factors, namely eIF2β/eIF5 and eIF2Bγ/eIF2Bε, differ from each other by the presence or absence of the W2 domain (Fig. 2). This observation supports the mobility of the W2 domain early in eukaryotic evolution, probably under selection driven by the emergence of additional functions in eIF2β and other regulatory interactions such as those with the MNK1 kinase.

Evolution of the Eukaryotic Translation Initiation System

Eukaryotes possess several unique components of the translation initiation system (Table 1). Preliminary searches in eukaryotes that have branched prior to the radiation of the crown group (e.g., Plasmodium falciparum; G. Subramanian, E.V. Koonin, and L. Aravind, unpub.) show that several of these proteins should have been present already in their common ancestor. Some of these proteins/domains clearly have been recruited from families that were present in the common ancestor of eukaryotes and archaea. These include the RNA helicase eIF4A, the nucleotidyltransferase and I-patch domains of eIF2Bγ/ε, and the GTPase subunit (γ) of eIF2. The case of eIF2C is less clear because this poorly characterized translation factor (Zou et al. 1998) is highly conserved in several, but not all, eukaryotes. We have detected divergent homologs of this protein in a number of archaea (L. Aravind and E.V. Koonin, unpub.), which suggests its emergence in the common ancestor of the archaeal–eukaryotic lineage, but whether or not this protein is involved in translation in archaea remains unclear.

The eIF3 and eIF4 complexes are clearly of eukaryotic provenance. Both these complexes contain α-helical domains that are unique to eukaryotes and participate in multiple adapter functions. A significant part of the eIF3 complex is composed of proteins containing JAB/PAD and PINT domains. These proteins or their paralogs are subunits of other large eukaryotic protein complexes, namely, the signalosome and the proteasome regulatory (lid-specific) complex (Aravind and Ponting 1998; Hofmann and Bucher 1998; Wei and Deng 1999). It seems likely that this complex had evolved as a general mediator of protein–protein interactions and had been recruited to function in different contexts by duplication and addition of new specific subunits. JAB appears to be an ancient domain that probably functions as an enzyme in prokaryotes (Ponting et al. 1999; L. Aravind, unpub.), whereas its inactive versions had been recruited for protein–protein interactions and regulatory functions in eukaryotes. The other major component of these complexes, the PINT domain, can be confidently detected only in eukaryotes and appears to have an entirely α-helical structure (Aravind and Ponting 1998). In the eIF4 complex, the principal adapter domain appears to be the helical NIC domain, which is also seen in other protein complexes such as the nuclear cap-binding complex and the RNA-degradation-associated NMD complex. The predicted MI and W2 domains that are found in different eukaryotic initiation factors also appear to possess α-helical structure and probably emerged early in the evolution of eukaryotes.

The remaining detectable domains of the eIF subunits are RRM and the WD40-type β-propeller, which are prevalent in eukaryotes. The folds found in these proteins are, however, ancient and predate the radiation of the three main divisions of life. Several other initiation factors such as eIF4E, eIF3-p150 and p163 (TIF32p) have homologs only in eukaryotes and contain no detectable domains shared with any other proteins. Of these, eIF4E surprisingly has a novel α/β fold that so far has not been seen in other proteins, whereas the rest are predicted to have a high α-helix content (Table 1).

This distribution of sequence similarity and structural features suggests that eukaryotes have recruited domains for translation initiation factors from new protein families that arose through rapid sequence evolution of preexisting folds and underwent an expansion early in the evolution of eukaryotes (Table 2). The predominance of α-helical domains with no apparent equivalents in the other main divisions of life suggests that such domains are easier to invent than those of the α/β and all-β classes—eIF4E seems to be the only new α/β fold involved in translation (Table 2). Once invented, new domains get fixed in sequence space if they are recruited for critical functions such as translation or transcription. In cases like the PINT and NIC domains, however, there is clear evidence for participation in diverse complexes, which suggests that these domains emerged as general protein–protein interaction adapters and have diversified into specific niches after subsequent duplications.

Table 2.

Number of Known or Predicted Domains of Different Structural Classes in Translation Factors in the Tree Primary Divisions of Life

| Phyletic distributiona | Protein structural class | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| all α-helix | all β-sheetb | α + β | |

| Eukarya + Archaea + Bacteria | — | 2 | 1 |

| Eukarya + Archaea | 1 | 2/2 ancient folds | 3/1 ancient fold |

| Eukarya | 9 | 2/2 ancient folds | 9/8 ancient folds |

Instances of likely horizontal transfer (Table 1) were not considered.

The cases where a lineage-specific initiation factor contains a domain belonging to an ancient fold are shown by “/”.

A number of unique domain fusion events can be seen in the eukaryotic translation initiation factors, but in archaea only one such case, the fusion of a paralog of eIF5A with NMD3 (Figure 2), is observed. eIF4G, in particular, has undergone domain accretion in the course of the origin of multicellular eukaryotes (Figure 2). The yeast versions contain only one detectable conserved module, the predicted NIC domain. In contrast, the animal and plant proteins additionally contain the MI domain located carboxyl-terminally of the NIC domain, with only the animal proteins having a further addition of the carboxyl-terminal W2 domain. This suggests that eIF4G has acquired new regulatory functions in multicellular eukaryotes through the binding specificities conferred by the accretion of additional domains. Modification of this key adapter in the course of evolution therefore appears to be one of the flexible points that allows new inputs to be received by the otherwise rigidly conserved translation initiation system.

Thus the eukaryotic translation initiation system contains a number of specific (predicted) domains that are absent in archaea and bacteria and that seem to serve as focal points for new regulatory interactions. On the basis of the detection of these conserved domains and their arrangement in proteins, we predict new regulators of translation or RNA metabolism. Experimental investigation of specific functions of the predicted domains discussed here should further our understanding of the regulation of translation initiation, a critical step in eukaryotic gene expression.

METHODS

Protein Sequence Analysis

The initial characterization of the phyletic distribution of each protein, delineation of likely orthologous relationships, and detection of other homologs were based on a single-pass gapped BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997) search of the nonredundant (NR) protein sequence database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NIH, Bethesda). Further, in-depth analysis was performed using iterative PSI-BLAST searches with profile inclusion cut-off of E (expectation) = 0.01 and several different starting queries extracted from the results of the first-pass search (Altschul et al. 1997). Significance of the matches was assessed in terms of the E-value obtained on first detection of the given sequence over the 0.01 threshold in the process of iterative searches. In addition, to eliminate false-positives that may emerge owing to compositional bias of a particular query, it was checked whether, in the iterative searches, different queries from a domain family consistently retrieved approximately the same set of proteins from the database. Multiple alignments of protein sequences were constructed by parsing pairwise alignments generated by PSI-BLAST and realigning them using the CLUSTALW program (Thompson et al. 1994), followed by manual refinement. Protein secondary structure prediction was performed using the PHD (Rost and Sander 1993) and PSIPRED (Jones 1999) programs.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL aravind@ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; FAX (301) 480-9241.

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki H, Adams SL, Turner MA, Ganoza MC. Molecular characterization of the prokaryotic efp gene product involved in a peptidyltransferase reaction. Biochimie. 1997;79:7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)87619-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Koonin EV. Gleaning non-trivial structural, functional and evolutionary information about proteins by iterative database searches. J Mol Biol. 1999a;287:1023–1040. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Novel predicted RNA-binding domains associated with the translation machinery. J Mol Evol. 1999b;48:291–302. doi: 10.1007/pl00006472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Ponting CP. Homologues of 26S proteasome subunits are regulators of transcription and translation. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1250–1254. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano K, Krishnamoorthy T, Phan L, Pavitt GD, Hinnebusch AG. Conserved bipartite motifs in yeast eIF5 and eIF2Bε, GTPase-activating and GDP-GTP exchange factors in translation initiation, mediate binding to their common substrate eIF2. EMBO J. 1999;18:1673–1688. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano K, Phan L, Anderson J, Hinnebusch AG. Complex formation by all five homologues of mammalian translation initiation factor 3 subunits from yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18573–18585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA. Upf1 and Upf2 proteins mediate normal yeast mRNA degradation when translation initiation is limited. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2433–2441. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.10.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battiste JL, Pestova TV, Hellen CU, Wagner G. The eIF1A solution structure reveals a large RNA-binding surface important for scanning function. Mol Cell. 2000;5:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80407-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belk JP, He F, Jacobson A. Overexpression of truncated Nmd3p inhibits protein synthesis in yeast. RNA. 1999;5:1055–1070. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe BJ, Bowman JA, McCracken S, Rosonina E. SR-Related proteins and the processing of messenger RNA precursors. Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;77:277–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SK, Lee JH, Zoll WL, Merrick WC, Dever TE. Promotion of Met-tRNAiMet binding to ribosomes by yIF2, a bacterial IF2 homolog in yeast. Science. 1998;280:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cmarik JL, Min H, Hegamyer G, Zhan S, Kulesz-Martin M, Yoshinaga H, Matsuhashi S, Colburn NH. Differentially expressed protein Pdcd4 inhibits tumor promoter-induced neoplastic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:14037–14042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AW, Haghighat A, Yu AT, Sonenberg N. Interaction of polyadenylate-binding protein with the eIF4G homologue PAIP enhances translation. Nature. 1998;392:520–523. doi: 10.1038/33198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Hagan KW, Zhang S, Peltz SW. Identification and characterization of genes that are required for the accelerated degradation of mRNAs containing a premature translational termination codon. Genes Dev. 1995;9:423–436. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gregorio E, Preiss T, Hentze MW. Translation driven by an eIF4G core domain in vivo. EMBO J. 1999;18:4865–4874. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever TE. Translation initiation: Adept at adapting. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:398–403. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez D, Altmann M, Benz J, Baumann U, Trachsel H. Interaction of translation initiation factor eIF4G with eIF4A in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26720–26726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortes P, Kufel J, Fornerod M, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Lafontaine D, Tollervey D, Mattaj IW. Genetic and physical interactions involving the yeast nuclear cap-binding complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6543–6553. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer C, Altmann M, Lee HS, Blanc A, Deshmukh M, Woolford JL, Jr, Trachsel H, Sonenberg N. TIF4631 and TIF4632: Two yeast genes encoding the high-molecular-weight subunits of the cap-binding protein complex (eukaryotic initiation factor 4F) contain an RNA recognition motif-like sequence and carry out an essential function. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4860–4874. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Brown AH, Jacobson A. Upf1p, Nmd2p, and Upf3p are interacting components of the yeast nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1580–1594. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henis-Korenblit S, Strumpf NL, Goldstaub D, Kimchi A. A novel form of DAP5 protein accumulates in apoptotic cells as a result of caspase cleavage and internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:496–506. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.496-506.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J. H. and Johnson, A.W. 1999. NMD3 encodes an essential cytoplasmic protein required for stable 60S ribosomal subunits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 19: 2389–2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hofmann K, Bucher P. The PCI domain: A common theme in three multiprotein complexes. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:204–205. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imataka H, Olsen HS, Sonenberg N. A new translational regulator with homology to eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G. EMBO J. 1997;16:817–825. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imataka H, Sonenberg N. Human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) possesses two separate and independent binding sites for eIF4A. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6940–6947. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde E, Lewis J, McGuigan C, Jankowska M, Darzynkiewicz E, Mattaj IW. A nuclear cap binding protein complex involved in pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 1994;78:657–668. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WG, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Fire A. Distinct requirements for somatic and germline expression of a generally expressed Caernorhabditis elegans gene. Genetics. 1997;146:227–238. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CY, Takahashi K, Nguyen TB, Roberts JK, Webster C. Identification of a nucleic acid binding domain in eukaryotic initiation factor eIFiso4G from wheat. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10603–10608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KK, Hung LW, Yokota H, Kim R, Kim SH. Crystal structures of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A from Methanococcus jannaschii at 1.8 Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10419–10424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV. Multidomain organization of eukaryotic guanine nucleotide exchange translation initiation factor eIF-2B subunits revealed by analysis of conserved sequence motifs. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1608–1617. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber P, Zander T, Herschlag D, Bardwell JC. A new heat shock protein that binds nucleic acids. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:249–256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laalami S, Grentzmann G, Bremaud L, Cenatiempo Y. Messenger RNA translation in prokaryotes: GTPase centers associated with translational factors. Biochimie. 1996;78:577–589. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(96)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laalami S, Sacerdot C, Vachon G, Mortensen K, SperlingPetersen HU, Cenatiempo Y, Grunberg-Manago M. Structural and functional domains of E. coli initiation factor IF2. Biochimie. 1991;73:1557–1566. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamphear BJ, Kirchweger R, Skern T, Rhoads RE. Mapping of functional domains in eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) with picornaviral proteases. Implications for cap-dependent and cap-independent translational initiation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21975–21983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Choi SK, Roll-Mecak A, Burley SK, Dever TE. Universal conservation in translation initiation revealed by human and archaeal homologs of bacterial translation initiation factor IF2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4342–4347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Strumpf N, Deiss LP, Berissi H, Kimchi A. DAP-5, a novel homolog of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G isolated as a putative modulator of gamma interferon-induced programmed cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1615–1625. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Aravind L, Galperin MY, Grishin NV, Tatusov RL, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Comparative genomics of the Archaea (Euryarchaeota): Evolution of conserved protein families, the stable core, and the variable shell. Genome Res. 1999;9:608–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotrigiano J, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Burley SK. Cocrystal structure of the messenger RNA 5′ cap-binding protein (eIF4E) bound to 7-methyl-GDP. Cell. 1997;89:951–961. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Cap-dependent translation initiation in eukaryotes is regulated by a molecular mimic of eIF4G. Mol Cell. 1999;3:707–716. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo H, Li H, McGuire AM, Fletcher CM, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Wagner G. Structure of translation factor eIF4E bound to m7GDP and interaction with 4E-binding protein. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:717–724. doi: 10.1038/nsb0997-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morino S, Imataka H, Svitkin YV, Pestova TV, Sonenberg N. Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding site and the middle one-third of eIF4GI constitute the core domain for cap-dependent translation, and the C-terminal one-third functions as a modulatory region. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:468–477. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.468-477.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff CL, Sachs AB. Eukaryotic translation initiation factors 4G and 4A from Saccharomyces cerevisiae interact physically and functionally. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5557–5564. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osherov N, Wang N, Loomis WF. Precocious sporulation and developmental lethality in yelA null mutants of Dictyostelium. Dev Genet. 1997;20:307–319. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1997)20:4<307::AID-DVG2>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peat TS, Newman J, Waldo GS, Berendzen J, Terwilliger TC. Structure of translation initiation factor 5A from Pyrobaculum aerophilum at 1.75 Å resolution. Structure. 1998;6:1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova TV, Borukhov SI, Hellen CU. Eukaryotic ribosomes require initiation factors 1 and 1A to locate initiation codons. Nature. 1998;394:854–859. doi: 10.1038/29703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova TV, Hellen CU. Ribosome recruitment and scanning: What's new? Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:85–87. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova TV, Lomakin IB, Lee JH, Choi SK, Dever TE, Hellen CU. The joining of ribosomal subunits in eukaryotes requires eIF5B. Nature. 2000;403:332–335. doi: 10.1038/35002118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponting CP, Aravind L, Schultz J, Bork P, Koonin EV. Eukaryotic signalling domain homologues in archaea and bacteria. Ancient ancestry and horizontal gene transfer. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:729–745. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiocho FA, Hu G, Gershon PD. Structural basis of mRNA cap recognition by proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:78–86. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B, Sander C. Prediction of protein secondary structure at better than 70% accuracy. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:584–599. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sette M, van Tilborg P, Spurio R, Kaptein R, Paci M, Gualerzi CO, Boelens R. The structure of the translational initiation factor IF1 from E. coli contains an oligomer-binding motif. EMBO J. 1997;16:1436–1443. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibahara K, Asano M, Ishida Y, Aoki T, Koike T, Honjo T. Isolation of a novel mouse gene MA-3 that is induced upon programmed cell death. Gene. 1995;166:297–301. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei N, Deng XW. Making sense of the COP9 signalosome. A regulatory protein complex conserved from Arabidopsis to human. Trends Genet. 1999;15:98–103. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01670-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf YI, Aravind L, Grishin NV, Koonin EV. Evolution of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases—analysis of unique domain architectures and phylogenetic trees reveals a complex history of horizontal gene transfer events. Genome Res. 1999;9:689–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton JC, Federhen S. Analysis of compositionally biased regions in sequence databases. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:554–571. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka S, Poksay KS, Arnold KS, Innerarity TL. A novel translational repressor mRNA is edited extensively in livers containing tumors caused by the transgene expression of the apoB mRNA-editing enzyme. Genes Dev. 1997;11:321–333. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou C, Zhang Z, Wu S, Osterman JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a rabbit eIF2C protein. Gene. 1998;211:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]