Summary

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are critical components of the antimicrobial repertoire of macrophages, yet the mechanisms by which ROS damage bacteria in the phagosome are unclear. The NADH-dependent phagocytic oxidase produces superoxide, which dismutes to form H2O2. The Barras and Méresse labs use a GFP fusion to an OxyR regulated gene to show that phagocyte-derived H2O2 is gaining access to the Salmonella cytoplasm. However, they have also shown previously that Salmonella has redundant systems to detoxify this H2O2. Although Salmonella propagate in a unique vacuole, their data suggest that ROS are not diminished in this modified phagosome. These recent results are put into the context of our overall understanding of potential oxidative bacterial damage occurring in macrophages.

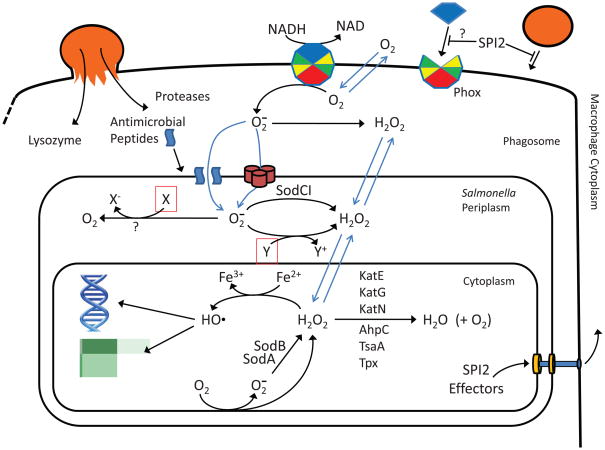

Macrophages engulf and kill bacteria. Although the overall role of macrophages has been known for over 100 years, we understand surprisingly little of the actual mechanisms by which bacteria are destroyed. The cell biology of phagolysosomal formation is fairly well understood. Macrophages recognize and engulf bacteria into phagosomes, which subsequently acidify. These phagosomes mature into phagolysosomes upon vesicle-mediated delivery of various antimicrobial effectors, which include proteases, antimicrobial peptides, and lysozyme (Garin et al., 2001)(Figure 1). The phagolysosome is also a nutrient-limiting environment. Reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species are produced in this compartment. The multi-subunit NADPH-dependent phagocytic oxidase (Phox or NOX2) is assembled on the phagolysosome membrane and pumps electrons into the compartment to reduce oxygen to superoxide anion (O2−). The inducible nitric oxide synthase uses arginine and oxygen as substrates to produce nitric oxide (Fang, 2004).

Figure 1. Reactive oxygen species in the Salmonella containing vacuole.

The phagocytic oxidase (Phox) produces O2− which enters the periplasm through porins or perhaps crosses the outer membrane that is partially permeabilized by antimicrobial peptides. This superoxide potentially kills or inhibits cells by reducing or oxidizing unknown targets. SodCI protects the cell by dismuting superoxide to hydrogen peroxide, which can freely diffuse across membranes into the cytoplasm. This species can cause the same damage as endogenously produced peroxide, all via Fenton chemistry. However, Salmonella produces six catalases or peroxidases that are capable of keeping the peroxide levels below 5 μM. The SCV is created by the action of SPI2 effector proteins injected into the macrophage cytoplasm that block vesicular trafficking and lessen the delivery of antimicrobial compounds. The assembly of Phox on the phagosomal membrane might also be decreased, but not to an extent that has phenotypic consequences. The shown chemical reactions are not necessarily balanced.

Most bacteria are rapidly killed and degraded in the phagolysosome, making it difficult to dissect the mechanism of death. But a few bacteria have evolved to survive in macrophages. Salmonella use a type III secretion system to affect vesicular trafficking and maturation of the phagolysosome (Holden, 2002). It is presumed that the bacteria within this modified “Salmonella containing vacuole” (SCV) are subjected to a less intense antimicrobial response. However, the phagocytic arsenal still has a role in Salmonella pathogenesis and the bacteria must also be resistant to these antimicrobial factors. This balance between survival and killing makes Salmonella a powerful model to understand the mechanisms of action of the phagocytic effectors.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are critical weapons in the phagocyte arsenal. In theory, O2− and nitric oxide can combine to form highly reactive peroxynitrite (ONOO−). But the roles of Phox and iNOS are both temporally (Vazquez-Torres et al., 2000a) and genetically (Craig and Slauch, 2009) separable during Salmonella infection, suggesting that ONOO− is irrelevant when combating this pathogen. Studies by Aussel et al. (2011), reported in this volume, provide important information regarding Salmonella resistance to the ROS produced by Phox, and suggest that Salmonella relies less on blocking ROS formation than on scavenging.

How do ROS damage the bacterial cell?

Our current understanding of potential mechanisms of ROS damage comes primarily from studies in E. coli that have, importantly, focused on cytoplasmic ROS/damage. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are produced inadvertently in the cytoplasm primarily when oxygen collides with various redox enzymes that have solvent-exposed flavins (Imlay, 2009). Superoxide can undergo spontaneous dismutation in a pH- and concentration-dependent reaction to yield H2O2 and O2; the same reaction is catalyzed by superoxide dismutases. Both O2− and H2O2 can damage a variety of biomolecules (Anjem et al., 2009;Imlay, 2009). These species can oxidize solvent exposed 4Fe-4S clusters. They can also damage other enzymes, most likely via a Fenton reaction with iron that is bound as a non-redox cofactor. These types of damage result in metabolic defects, including auxotrophy for aromatic, branched-chain, and sulfur-containing amino acids. Damage to iron-sulfur clusters releases iron, which can undergo a Fenton reaction with H2O2 to yield hydroxyl radical, which damages any biological molecule, including DNA, in a diffusion limited manner. Fenton chemistry can also result in carbonylation of proteins. Hydrogen peroxide can directly react with cysteine residues, depending on the local environment of the sulfhydryl group. Superoxide cannot damage membranes in bacteria, as lipid peroxidation requires polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Are these cytoplasmic injuries relevant to what is happening in the phagosome?

The answer is apparently no. Phagocytes are estimated to produce relatively high amounts of O2−, on the order of 0.5 mM/sec (Imlay, 2009). Taking into account the rate of spontaneous dismutation and approximate volume of the phagosome, this is estimated to yield 50 μM O2− at pH 7.4 or 2 μM at pH 4.5, the approximate pH of the acidified phagosome. Because the resulting H2O2 can diffuse across membranes, including out of the phagosome, the steady state concentration of the H2O2 would be approximately 1–4 μM. The H2O2 that diffuses into the bacterial cytoplasm could potentially cause damage. Indeed, dogma is that the phagocytic ROS kill bacteria by damaging DNA. But Salmonella produces three catalases and three hydroperoxide reductases, all cytoplasmic, that can scavenge H2O2. Hebrard et al. showed that Salmonella strains lacking catalases alone, or two of three peroxidases alone, remained fully virulent, whereas the mutant missing five enzymes was attenuated (Hebrard et al., 2009). More recently, a third peroxidase was identified that also contributes to H2O2 scavenging (Horst et al., 2010). These important results show that Salmonella is more than capable of handling the H2O2 that results from the oxidative burst. In E. coli, aromatic amino acid auxotrophy and DNA damage are observed at ~0.5 μM cytoplasmic H2O2. It is known that Salmonella mutants that are incapable of synthesizing aromatic amino acids are significantly attenuate. Thus we can infer that this pathway is intact and that the cytoplasmic H2O2 concentration is below 0.5 μM in the scavenging-competent bacteria.

In this volume, Aussel et al. (2011) further characterize Salmonella resistance to the oxidative burst by constructing a reporter strain containing an ahpC promoter-Gfp fusion. The ahpC gene encodes a peroxidase under the control of OxyR, which activates a series of genes in direct response to H2O2. They show that this fusion is induced when Salmonella are growing in macrophages and that induction is dependent on Phox. These data prove that H2O2 is gaining access to the bacterial cytoplasm at a concentration sufficient to induce OxyR, ≤ 100 nM (Imlay, 2009). Given the fact that the peroxide is being actively scavenged, this is consistent with the estimates for O2− and H2O2 production given above. Knocking out four of the six scavenging enzymes results in increased expression of the ahpC fusion, but this strain remains virulent. Moreover, although the OxyR regulon is induced in the SCV, it is not required; oxyR mutants are fully virulent (Taylor et al., 1998), consistent with the redundant protection provided by the various detoxifying enzymes. Thus, there does not appear to be substantial damage to cytoplasmic contents in Salmonella caused by phagocyte generated H2O2.

What of superoxide?

It is clear that phagocytic O2− damages bacteria in the phagosome and that the periplasmic superoxide dismutase SodCI protects Salmonella specifically against this exogenous O2− (Craig and Slauch, 2009, and references therein). Mutations in sodCI attenuate Salmonella, yet loss of periplasmic SOD confers no phenotype when Salmonella are grown in vitro or when the bacteria are infecting Phox−/− mice. Moreover, charged O2− cannot cross membranes and the role of SodCI is genetically separable from enzymes involved in protecting the cytoplasm from superoxide-mediated damage, including cytoplasmic superoxide dismutases. Thus, the primary targets of phagocytic O2− must be extracytoplasmic.

This extracytoplasmic damage is the result of O2− per se and not some downstream ROS. Spontaneous or enzymatic dismutation of O2−, in theory, yields the same amount of H2O2. SodCI simply lowers the steady state concentration of O2− in the periplasm. Aussel et al. (2011) used their ahpC-GFP fusion strain to monitor the amount of H2O2 that enters the cytoplasm of wild type Salmonella versus a mutant lacking periplasmic SOD. Surprisingly, they found that the H2O2 concentration was higher in the wild type cell. Simplistically, this suggests that in the SOD mutant, O2− is substantially consumed by some reaction that does not result the production of H2O2. SodCI normally prevents this latter reaction by driving the O2− to H2O2. Since both spontaneous dismutation and substrate oxidation convert O2− into H2O2, this result suggests that O2− is acting as a reductant in the periplasm. This is somewhat surprising since targets with the required redox potential are expected to be very limited. Further study will be required to resolve this conundrum and identify the most vulnerable target(s) of O2−. But this superoxide-mediated extracytoplasmic damage is at least as critical as the potential cytoplasmic damage caused by H2O2 and there is no reason to think that this is unique to Salmonella. Thus, identifying the targets of exogenous O2− is key to understanding the overall mechanism of oxidative damage in phagocytes.

Is Salmonella special in its ability to handle the oxidative burst?

Salmonella injects a series of proteins into the macrophage cytoplasm via the SPI2 type III secretion system leading to alterations in vesicular trafficking and the establishment of the SCV (Holden, 2002). Two groups have provided data suggesting that the assembly of Phox on the SCV membrane is also inhibited by SPI2 effectors (Gallois et al., 2001;Vazquez-Torres et al., 2000b). Clearly this proposed exclusion of Phox is not 100%, or there would be no role for SodCI. But, does this inhibition significantly lower the amount of O2− created in the SCV? Aussel et al. (2011) show that mutants defective in SPI2 secretion are equally attenuated in congenic wild type and Phox−/− mice, although both wild type and mutant bacteria propagate more readily in the Phox−/− host. These results suggest that SPI2 has a role that is functionally unrelated to the delivery or assembly of Phox. Both results could be correct, in that alterations in vesicular trafficking could decrease the delivery of Phox, but any decrease in phagosomal ROS formation may be too moderate to affect bacterial survival. These new results will certainly generate further study, but they do emphasize the power of competition assays in sorting out complicated host-pathogen interactions (Craig and Slauch, 2009).

Mice and humans defective in Phox are clearly more susceptible to Salmonella. Aussel et al., for example, recovered >1 log more Salmonella from the spleens of Phox−/− mice than from those of wild type mice. Does this mean that the oxidative burst is indeed killing a large fraction of the wild type Salmonella? This is not clear. There is ample evidence that O2− and downstream ROS not only directly damage bacteria, but also are critical for signaling and activation of other antimicrobial effectors (Gwinn and Vallyathan, 2006;Forman and Torres, 2002). In other words, additional attenuation in the wild type mouse does not prove that this is the result of direct damage by phagocytic O2−.

Does superoxide act alone?

Antimicrobial peptides in the SCV can partially disrupt the outer membrane of Salmonella and allow access of phagocytic proteases to periplasmic proteins (Kim et al., 2010). Importantly, this is occurring in Salmonella cells that survive this assault and go on to kill the animal. Indeed, data suggest that SodCI is both tethered within the periplasm and protease resistant, allowing it to detoxify O2− in the face of this combined attack. Additional in vivo evidence of synergism between phagocytic effectors is surprisingly limited. Rosenberger et al. showed that the addition of protease inhibitors to macrophages in culture also blocked proteolytic processing and activation of antimicrobial peptides (Rosenberger et al., 2004). But one can imagine more intimate synergy at the level of damage. Perhaps antimicrobial peptides are required to facilitate O2− access to a periplasmic target. Alternatively, superoxide-mediated damage could make the cell susceptible to some other antimicrobial effector.

What’s next?

These recent studies have emphasized the differences in our understanding of endogenous versus exogenous ROS-mediated damage. In effect, they have told us what is NOT damaged by phagocytic ROS; we still have not identified the pertinent targets of the phagocytic oxidative burst. The problem is complicated by our inability to produce O2− in the laboratory at concentrations that approach, even perhaps within an order of magnitude, those apparently produced in the phagosome (Craig and Slauch, 2009). The good news is that the sophisticated molecular and genetic tools available in Salmonella should enable us to address these questions.

Acknowledgments

I thank Jim Imlay for helpful discussions and comments. This work was supported by AI080705 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Anjem A, Varghese S, Imlay JA. Manganese import is a key element of the OxyR response to hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:844–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aussel L, Zhao W, Hébrard M, Guilhon AA, Viala J, Henri S, Chasson L, Gorvel JP, Barras F, Méresse S. Salmonella detoxifying enzymes are sufficient to cope with the host oxidative burst. Mol Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07611.x. MMI-2010-10662.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig M, Slauch JM. Phagocytic superoxide specifically damages an extracytoplasmic target to inhibit or kill Salmonella. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang FC. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: concepts and controversies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:820–832. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman HJ, Torres M. Reactive oxygen species and cell signaling: respiratory burst in macrophage signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:S4–S8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2206007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallois A, Klein JR, Allen LA, Jones BD, Nauseef WM. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-encoded type III secretion system mediates exclusion of NADPH oxidase assembly from the phagosomal membrane. J Immunol. 2001;166:5741–5748. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garin J, Diez R, Kieffer S, Dermine JF, Duclos S, Gagnon E, et al. The phagosome proteome: insight into phagosome functions. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:165–180. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn MR, Vallyathan V. Respiratory burst: role in signal transduction in alveolar macrophages. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2006;9:27–39. doi: 10.1080/15287390500196081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebrard M, Viala JP, Meresse S, Barras F, Aussel L. Redundant hydrogen peroxide scavengers contribute to Salmonella virulence and oxidative stress resistance. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4605–4614. doi: 10.1128/JB.00144-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden DW. Trafficking of the Salmonella vacuole in macrophages. Traffic. 2002;3:161–169. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst SA, Jaeger T, Denkel LA, Rouf SF, Rhen M, Bange FC. Thiol peroxidase protects Salmonella enterica from hydrogen peroxide stress in vitro and facilitates intracellular growth. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2929–2932. doi: 10.1128/JB.01652-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay JA. Oxidative stress. In: Böck A, Curtis R3, Kaper J, Karp PD, Neidhardt FC, Nystrom T, et al., editors. EcoSal-Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Richards SM, Gunn JS, Slauch JM. Protecting from antimicrobial effectors in the phagosome allows SodCII to contribute to virulence in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2140–2149. doi: 10.1128/JB.00016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger CM, Gallo RL, Finlay BB. Interplay between antibacterial effectors: a macrophage antimicrobial peptide impairs intracellular Salmonella replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2422–2427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304455101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PD, Inchley CJ, Gallagher MP. The Salmonella typhimurium AhpC polypeptide is not essential for virulence in BALB/c mice but is recognized as an antigen during infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3208–3217. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3208-3217.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Mastroeni P, Ischiropoulos H, Fang FC. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. I. Effects on microbial killing by activated peritoneal macrophages in vitro. J Exp Med. 2000a;192:227–236. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Torres A, Xu Y, Jones-Carson J, Holden DW, Lucia SM, Dinauer MC, et al. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent evasion of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Science. 2000b;287:1655–1658. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]