Abstract

Due to growing work-family demands, supervisors need to effectively exhibit family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). Drawing on social support theory and using data from two samples of lower wage workers, the authors develop and validate a measure of FSSB, defined as behaviors exhibited by supervisors that are supportive of families. FSSB is conceptualized as a multidimensional superordinate construct with four subordinate dimensions: emotional support, instrumental support, role modeling behaviors, and creative work-family management. Results from multilevel confirmatory factor analyses and multilevel regression analyses provide evidence of construct, criterion-related, and incremental validity. The authors found FSSB to be significantly related to work-family conflict, work-family positive spillover, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions over and above measures of general supervisor support.

Keywords: work and family, supervisor support, measurement development

Extensive changes have occurred over the past 30 to 40 years in employee and family roles, as well as in the relationship between work and family domains. Evidence of these changes includes the increasing percentage of families supported by dual incomes, increases in workers with multiple family-care responsibilities, growing numbers of single parents in the workforce, and greater gender integration into organizations (Kossek & Lambert, 2005; Neal & Hammer, 2007). Although these labor market shifts have been coupled with a corresponding trend toward greater organizational adoption of formal family supportive policies (e.g., Glass & Fujimoto, 1995; Goodstein, 1994; Ingram & Simons, 1995; Kelly, 2006; Kelly & Dobbin, 1999; Milliken, Martins, & Morgan, 1998; Osterman, 1995), researchers suggest that the existence of such policies is a necessary but insufficient condition to alleviate employees' rising work and family demands and needs for greater flexibility (T. D. Allen, 2001; Kossek & Distelberg, 2009). Most workplaces that offer supports related to work hours, scheduling, and flexibility base these on the informal discretion of supervisors who directly influence employees' workload and work-related stressors (Beehr, Farmer, Glazer, Gudanowski, & Nair, 2003). Given the key role of supervisors in interpreting and enacting formal organizational policy and informal practice, the study of supervisor support for work and family is critical to understanding how to effectively implement work and family policies in employing organizations (Hopkins, 2005).

Drawing on the general social support literature (Cohen & Wills, 1985), work-family research has identified social support from supervisors as an important resource that can reduce the negative effects of work and family stressors (e.g., O'Driscoll et al., 2003; Thomas & Ganster, 1995). Social support is an interpersonal transaction that may include emotional expression of concern, instrumental assistance, or information (House, 1981). Supervisor support, a source of social support, is related to lower levels of employee work-family conflict (e.g., Frone, Yardley, & Markel, 1997; Frye & Breaugh, 2004; Lapierre & Allen, 2006; Thomas & Ganster, 1995; Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999). Moreover, high levels of supervisor support can benefit employees as a resource and have been related to higher levels of work-family positive spillover (Thompson & Prottas, 2005). In addition, supervisor support has been shown to enhance employee job attitudes such as job satisfaction (Thomas & Ganster, 1995; Thompson & Prottas, 2005) and is negatively related to turnover intentions (Thompson et al., 1999; Thompson & Prottas, 2005).

Most prior research on supervisor support and work-family outcomes has been based on general measures of emotional support, as opposed to the identification of specific supervisor behaviors that are supportive of the family role, as demonstrated in a recent meta-analysis (Kossek, Pichler, Hammer, & Bodner, 2007). Furthermore, this meta-analysis demonstrated that measures of supervisor support for the family role tend to have stronger relationships with work-family conflict outcomes than measures that are not specific to the family role (i.e., general measures of supervisor support), consistent with what Ajzen (1988) calls the “principal of compatibility” (p. 92). It is important to note that although specific measures may be better predictive of specific outcomes, they are potentially not as effective at predicting more general outcomes. Given that our measure is focused on supervisor support for the family role, theoretically, this tradeoff is acceptable.

In addition, based on our review of the literature, we conclude that there is a lack of measures of behavioral supervisor support in general. An exception is a recent measure of supervisor supportive and unsupportive behaviors developed by Rooney and Gottlieb (2007). Given that this measure is not specific to support for the family role, we still see a need to provide management with prescriptive information about what supervisors should actually do to be more supportive of workers with work-family demands. In addition, more research is needed to develop measures that enable researchers to assess supervisor support for family, distinctive from work-family culture and climate, as some exiting measures of supervisor support are contaminated with more general measures of culture. Such work will enable scholars to better assess whether supervisor support is an antecedent to a supportive work-family culture or climate, a subfacet of culture or climate, or an outcome of a supportive culture.

Therefore, we suggest that there are both research and practical reasons to develop a measure that identifies the behaviors that supervisors should engage in to help employees better manage work and family. Building on the work of several relevant conceptual studies, the goal of this study was to address these gaps and develop a valid, empirically based measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). Conceptually, FSSB is defined as those behaviors exhibited by supervisors that are supportive of families and consists of the following four dimensions—emotional support, instrumental support, role modeling behaviors, and creative work-family management (i.e., managerial-initiated actions to restructure work to facilitate employee effectiveness on and off the job)—based on the work of Hammer, Kossek, Zimmerman, and Daniels (2007).

We draw on Hammer et al.'s (2007) conceptualization of FSSB and develop a measure that reflects the multidimensional nature of the construct. We also rely on the meta-analysis conducted by Kossek et al. (2007) on the relationship between workplace support and work-family conflict, which showed work-family specific measures of supervisor support to have the most robust relationships to work-family conflict measures. In the following sections, we review the research on supervisor support and provide a rationale for the construct of FSSB. Then, in two studies, we develop a measure to assess FSSB and provide evidence of construct, criterion-related, and incremental validity. In particular, we relate the measure to the outcomes of work-family conflict, work-family positive spillover, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions, outcomes that have been shown to be related to emotional supervisor support in prior research.

The Construct of Supervisor Support

Supervisor support is one source of social support from work and is also referred to as a form of informal organizational support (e.g., Hammer et al., 2007). As suggested by Hammer et al., there is a lack of conceptual clarity in the measurement of informal organizational support, as measures include overall perceived organizational support (POS; Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoades, 2002), organizational work-family culture, overall supervisor support, and work-family specific supervisory support. At times, these measures are contaminated with items that cut across these different types of informal support. For example, one measure of work-family organizational culture also includes some items related to supervisor support (cf. Thompson et al., 1999).

The family supportive supervisor has been defined as one who empathizes with an employee's desire to seek balance between work and family responsibilities (Thomas & Ganster, 1995). Furthermore, informal supervisor support for work and family may be more important to employees' overall well-being than the provision of formal workplace policies and supports for family such as alternative work schedule policies and dependent care supports (e.g., T. D. Allen, 2001; Behson, 2005; Kossek & Nichol, 1992). Organizational scholars have demonstrated that employees who have supportive supervisors experience less work-family conflict (Anderson, Coffey, & Byerly, 2002; Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1997; Goff, Mount, & Jamison, 1990; Lapierre & Allen, 2006; Thompson & Prottas, 2005), have reduced work distress (Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1997), have less absenteeism (Goff et al., 1990), have reduced intentions to quit (Thompson et al., 1999), and have increased job satisfaction (Thomas & Ganster, 1995; Thompson & Prottas, 2005).

Defining the Multidimensional Construct of FSSB

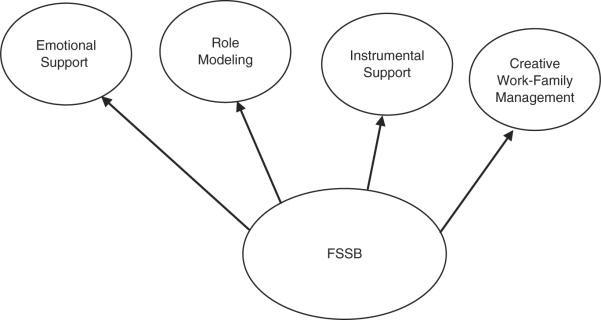

Recent work on the conceptual development of FSSB identified the four dimensions of emotional support, role modeling behaviors, instrumental support, and creative work-family management as being arranged hierarchically under the broader dimension of family supportive supervision (Hammer et al., 2007). Thus, we envision the multidimensional construct of FSSB as being a superordinate construct indicated by four subordinate constructs arranged hierarchically (Edwards, 2001; see Figure 1). As Edwards suggests, multidimensional constructs are superordinate when “relationships flow from the construct to its dimensions” (p. 145), and the multidimensional construct is not conceived of separately from the specific dimensions. We see this frequently in the personality literature such as the five-factor model of personality (Edwards, 2001). Similarly, the structure of overall and facet job satisfaction is another example of a superordinate construct with subordinate dimensions. In the following sections, we further delineate these four subordinate constructs of the broader superordinate FSSB construct.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical Model Representing the Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB) Construct

Emotional support generally is focused on perceptions that one is being cared for, that one's feelings are being considered, and that individuals feel comfortable communicating with the source of support when needed. Emotional supervisor support includes talking to workers and being aware of their family and personal life commitments. Supervisor emotional support involves the extent to which supervisors make employees feel comfortable discussing family-related issues, express concern for the way that work responsibilities affect family, and demonstrate respect, understanding, sympathy, and sensitivity in regard to family responsibilities. Other terms that have been used in the work-family literature to describe this domain are sensitivity (Hopkins, 2005; Warren & Johnson, 1995) and interactional support (Winfield & Rushing, 2005).

Role modeling behaviors refers to supervisors demonstrating how to integrate work and family through modeling behaviors on the job. In the context of family supportive supervision, role modeling can be defined as the extent to which supervisors provide examples of strategies and behaviors that employees believe will lead to desirable work-life outcomes. Social learning theory states that the vast majority of human learning occurs through the observation of others rather than through direct experience (Bandura, 1977). Furthermore, the literature suggests that cultural change will occur only when supervisors and other organizational leaders reinforce work-life values through what they say and do (Regan, 1994). Kirby and Krone (2002) suggest that for work-life policies to be adopted, they must become part of the organizational discourse through writing or oral communications, as well as role modeling.

The mentoring literature is also useful in illustrating how family supportive role modeling can benefit employees. For example, mentoring employees by sharing ideas or advice about strategies that have helped them or others they know successfully manage their work and family demands can be very beneficial. Greenhaus and Singh (2007) provide several examples of work-family mentoring behaviors, which supervisors could incorporate to better support their employees (e.g., discussing the consequences of different career paths, protecting the protégé from negative career consequences, or role modeling tolerance and decision making consistent with one's own work-life values).

Instrumental support is reactive and pertains to supervisor support as he or she responds to an individual employee's work and family needs in the form of day-to-day management transactions. These may include reacting to scheduling requests for flexibility, needs to interpret policies and practices, and managing routine work schedules to ensure that employees' job tasks get done. It is the extent to which supervisors provide day-to-day resources or services to assist employees in their efforts to successfully manage their dual responsibilities in work and family roles. This support is generally supervisors' routine reactions to manage day-to-day employee scheduling conflicts.

A fourth subordinate construct of FSSB is proactive, creative work-family management. Unlike instrumental support, which is more individually oriented, reactive, and typically initiated in response to an employee's request, creative work-family management is proactive, more strategic, and innovative. It is defined as managerial-initiated actions to restructure work to facilitate employee effectiveness on and off the job. These behaviors can involve major changes in the time, place, and way that work is done that simultaneously balances sensitivity to employees' work-family responsibilities with company, customer, and coworker needs.

Some examples of creative work-family management include being able to think about work-family demands in terms of the total work group in order to provide structural group interventions such as cross-training within and between work departments. This can be defined as the willingness and ability to challenge organizational assumptions that then result in the redesign of work to enhance organizational outcomes, while also facilitating employees' efforts to integrate work and family responsibilities (Hammer et al., 2007).

This conceptualization of creative work-family management is based on a small but growing literature illustrating the processes and benefits of dual agenda organizational change (Bailyn, 2003; Bailyn, Fletcher, & Kolb, 1997; Bailyn & Harrington, 2004; Kolb, Merrill-Sands, & Burke, 1999; Rapoport, Bailyn, Fletcher, & Pruitt, 2002; Rayman et al., 1999). Dual agenda refers to the notion that work can be designed to jointly support effectiveness at work and also effectiveness at home. Such behaviors require big-picture thinking that considers the implementation of support for family in the context of existing policies and practices. Creative work-family management, in its essence, refers to “win-win” actions where the supervisor initiates new ways to restructure work that are sensitive to both employee and company needs.

Existing Measures of Supervisor Support

Given our review of the four critical subordinate dimensions of FSSB that we argue should be part of any measure of supervisor support for family, we argue here that existing measures are clearly deficient, as most contain only the dimension of supervisor emotional support and only one measure also includes instrumental support (see Table 1). We know of no scales that include the dimensions of role modeling behaviors or creative work-family management. We see these dimensions as critical to the multidimensional construct of FSSB, as they involve managers proactively embracing work-family issues at both the personal role level as well as the managerial role level.

Table 1.

Cross-Tabulation of Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB) by Measurement Instruments

| FSSB Scale Dimension |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Supportive Supervisor Measure | Emotional Support | Role Modeling | Instrumental Support | Creative Work-Family Management |

| Clark, 2001 | x | |||

| Fernandez, 1986 | x | |||

| Galinsky, Hughes, & Shinn, 1986 | x | |||

| Kossek & Nichol, 1992 | x | |||

| Shinn, Wong, Simko, & Ortiz-Torres, 1989 | x | x | ||

| Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999 | x | |||

| Hammer et al. (this article) | x | x | x | x |

In reviewing existing measures of supervisor support, it is important to clarify that although general measures of emotional supervisor support exist (e.g., Caplan, Cobb, French, Harrison, & Pinneau, 1975; House, 1981; Yoon & Lim, 1999), we are focusing here on measures of supervisor support for family. Hammer et al. (2007) identified five existing measures of supervisor support for family (Clark, 2001; Fernandez, 1986; Galinsky, Hughes, & Shinn, 1986; Kossek & Nichol, 1992; Shinn, Wong, Simko, & Ortiz-Torres, 1989). In addition, the managerial support dimension of the Thompson et al. (1999) measure of work-family culture has been used as a measure of family supportive supervision and is an example of how the operationalization of the two constructs (work-family culture and family supportive supervision) have been confounded with one another. All but one of these scales is a unidimensional measure of emotional supervisor support. The Shinn et al. (1989) measure is an exception and appears to have items that mostly assess the instrumental dimension of supervisor support, however, there is at least one emotional support item in the scale, as well. To our knowledge, this is the only measure of family supportive supervisory behaviors in the literature and has been used by several work-family scholars (i.e., T. D. Allen, 2001; Frye & Breaugh, 2004; Thomas & Ganster, 1995). In addition, none of these measures appear to be systematically developed or validated using confirmatory factor analytic methods, including the Shinn et al. (1989) measure.

Criterion deficiency and contamination

We argue that these prior measures of family supportive supervision suffer from both criterion deficiency and criterion contamination. Specifically, prior measures of supervisor support do not capture all of the critical dimensions of family supportive supervision and, thus, are deficient. In addition, at least one of the measures of supervisor support for family is contaminated with items that measure work-family culture (e.g., Thompson et al., 1999). Thus, even if confirmatory factor analyses were conducted on prior measures, we argue that the measures are deficient as they do not contain all relevant dimensions of supervisor support for family, and at least one measure is contaminated with items that assess another construct, suggesting that the utility of any factor analyses on these measures would be limited. Therefore, we argue that there is a clear need for a measure that accurately depicts the full content domain of FSSB and that this measure would have both practical and theoretical value.

Summary

In summary, we propose that FSSB is a superordinate construct made up of the subordinate constructs of emotional support, role modeling behaviors, instrumental support, and creative work-family management, similar to the structure of personality or job satisfaction (Edwards, 2001). We ultimately expect that, overall, FSSB will be negatively related to both work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict. We also expect that FSSB will be positively related to job satisfaction and negatively related to turnover intentions. In addition, we expect that FSSB will significantly predict these noted outcomes over and above existing measures of supervisor support, thus demonstrating incremental validity of our new measure. This research involves two studies: one to develop the measure of FSSB and the other to validate the measure.

Study 1: FSSB Subordinate Construct Development

Focus Group/Item Development

Using a sample from a grocery store chain in the Northeastern United States, we conducted four focus groups with employees and supervisors separately, and four individual interviews with district managers, to identify critical supervisory behaviors that were representative of being family supportive. Based on this information, items for the FSSB measure were developed deductively from theory as articulated in the above sections and inductively from qualitative interviews. We conducted a content analysis of the data using an open-coding approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) to identify, categorize, and describe phenomena found in the focus group and individual interview transcripts. Survey items were generated and grouped into the appropriate supervisor supportive subordinate construct (i.e., emotional, instrumental, role modeling, or creative work-family management). A total of 28 items was identified by the team to represent the four dimensions of FSSB identified through our inductive (qualitative data) and deductive (literature and theory review) processes. The items were then reviewed by subject matter experts from the human resources department of a university in the Pacific Northwest, and several of the items were reworded for clarity based on their feedback. These items were assessed using a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Sample and Procedure

A Web survey was distributed to all classified staff (N = 585) (i.e., administrative positions, facilities and planning, public safety, health services, and research and accounting departments) at a university in the Pacific Northwest. A total of 148 people responded to the survey for a response rate of 27%. Although this response rate is less than what would have been desired, this is consistent with the mean response rate found in a meta-analysis of Web-based survey response rates, which was 34.6% with a standard deviation of 15.7% (Cook, Heath, & Thompson, 2000). For the analyses, we selected a subset (N = 123) of the sample that had family responsibilities (e.g., lived with a partner, had children, or cared for an aging parent). Survey completion was voluntary and anonymous, and the study was described to participants as research designed to examine their views on work and family issues. Participants were offered the opportunity to enter a drawing for one $100 gift certificate for a local department store.

Analyses and Results

We followed a two-stage process in the psychometric evaluation of the 28 items. In the first step, we employed conventional item analysis techniques to identify poorly performing items (M. J. Allen & Yen, 2002; Waltz, Strickland, & Lenz, 1991). In the second step, we performed exploratory factor analyses on the items in each subordinate dimension retained after the item analysis.

Multiple criteria were used in the item analysis to evaluate the psychometric properties of the 28 items. Frequencies, standard deviations, interitem correlations, item-total correlations, alpha if item deleted, item discriminations, and item difficulties were computed. As described by M. J. Allen and Yen (2002), item difficulties for Likert-type scales can be computed as the percentage of respondents endorsing the item (e.g., indicating that they agree or strongly agree). Item discriminations were computed by calculating the difference in item difficulty between participants scoring in the upper 33% on the dimension and those scoring in the lower 33% (M. J. Allen & Yen, 2002). Items were considered good if (a) less than 10% of respondents marked “not applicable,” (b) items showed strong to moderate correlations with the other items within their subordinate dimension and lower correlations with the items in other subordinate dimensions, (c) item total correlations with dimension were above .60, (d) Cronbach's alpha did not decrease more than .03 points and remained above .70, (e) item difficulties were between .30 and .70, and (f) item discriminations were above .30 (M. J. Allen & Yen, 2002; Waltz et al., 1991). The 28-item measure was refined based on the above analyses and resulted in a total of 18 items with the following subordinate dimensions: emotional support (5 items, alpha = .92), role modeling behaviors (3 items, alpha = .97), instrumental support (4 items, alpha = .88), and creative work-family management (6 items, alpha = .92).

It is unfortunate that this sample was not large enough to conduct a confirmatory or exploratory factor analysis on all 18 items of the superordinate FSSB measure with confidence. With 18 items and 4 correlated subordinate constructs, there are 18 factor loadings, 18 error variances, and 6 factor correlations for a total of 42 model parameters (we fixed the 4 factor variances to unity for model identification). Thus, the ratio of participants to model parameters is 123/42 = 2.93. This ratio was too small for confirmatory analyses and we chose to conduct confirmatory factor analyses based on our larger sample in Study 2. Instead, we conducted a separate exploratory factor analysis on each dimension using principle axis factoring. For each exploratory factor analysis, we evaluated the item dimensionality using Scree plots, item quality using item communalities and factor loadings, and model adequacy using the percentage of total variance explained. The initial solutions for all four of the dimensions (emotional support, role modeling behaviors, instrumental support, and creative work-life management) produced Scree plots suggesting the extraction of one factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1. The items for all four subordinate dimensions had adequate communalities: greater than .62 for the factor of emotional support, .83 for role modeling behaviors, .50 for instrumental support, and .46 for work-family creative management with the factors explaining total variance of 71.09%, 91.39%, 65.89%, and 67.96%, respectively. The factor loadings for each subdimension were also sufficiently large: greater than .79 for the factor of emotional support, .91 for role modeling behaviors, .70 for instrumental support, and .67 for work-family creative management. Cronbach's alpha was above .88 for all dimensions. This 18-item measure was used in the larger Study 2 described below.

Study 2: FSSB Superordinate Construct Validation

The purposes of Study 2 were threefold. First, we sought to evaluate the psychometric properties of the multidimensional, multilevel FSSB scale using a second-order factor analysis. Second, we sought to provide construct validity evidence for FSSB by relating the scores to scores from measures of similar constructs (convergent validity) and to scores on important outcome variables in the work-family literature (criterion-oriented validity). Third, given that there are existing measures of similar constructs, we sought to explore whether FSSB scale scores have additional predictive utility for these outcomes over and above these existing measures (incremental validity).

Sample and Procedure

Data were collected in 12 stores of a grocery store chain in the Midwestern United States as part of a larger study of work and family. Each store had at least 1 store manager and from 1 to 9 additional supervisors/department heads. The number of employees per store varied, ranging from 30 to 90. A total of 360 employees and 79 supervisors agreed to participate in the study on company time and each received a $25 gift card from the researchers. Surveys were administered individually in a face-to-face interview and the researchers helped interpret the survey questions when needed. The employees and supervisors completed almost identical survey instruments. The larger interview was made up of 196 survey-type questions and lasted between 35 and 50 minutes on average. This process led to virtually no missing data. Data were typically collected in managers' offices or in break rooms of the stores to give each participant as much privacy as possible.

Of the total 360 employees who participated in the survey, 27% or 97 were men and 73% or 262 were women. Approximately 92% were White with a mean age of 38 years. In terms of relationship demographics, 55% reported being married or living as married, 41% had children living at home, 16% were providing care for another adult, and 9% were providing care for a child and an adult.

Measures

Family supportive supervisor behaviors

This 18-item multidimensional scale included the items identified as useful in Study 1, representing each of four dimensions (emotional support, instrumental support, role modeling behaviors, and creative work-family management). Items were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (see Table 2 for final validated scale).

Table 2.

Factor Loadings and Error Variances for a Multilevel Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model for the Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB) From Study 2

| Factor | Item/Factor | Loading (SE) | Error Variance (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional support | 1. My supervisor is willing to listen to my problems in juggling work and nonwork life. | 1.00 | .30 (.04) |

| 2. My supervisor takes the time to learn about my personal needs. | 1.02 (.06) | .39 (.05) | |

| 3. My supervisor makes me feel comfortable talking to him or her about my conflicts between work and nonwork. | 1.16 (.06) | .25 (.04) | |

| 4. My supervisor and I can talk effectively to solve conflicts between work and nonwork issues. | 1.14 (.06) | .18 (.03) | |

| Instrumental support | 5. I can depend on my supervisor to help me with scheduling conflicts if I need it. | 1.00 | .53 (.05) |

| 6. I can rely on my supervisor to make sure my work responsibilities are handled when I have unanticipated nonwork demands. | .88 (.11) | .55 (.05) | |

| 7. My supervisor works effectively with workers to creatively solve conflicts between work and nonwork. | 1.30 (.14) | .22 (.04) | |

| Role model | 8. My supervisor is a good role model for work and nonwork balance. | 1.00 | .27 (.04) |

| 9. My supervisor demonstrates effective behaviors in how to juggle work and nonwork balance. | .93 (.04) | .22 (.03) | |

| 10. My supervisor demonstrates how a person can jointly be successful on and off the job. | .77 (.06) | .29 (.04) | |

| Creative work-family management | 11. My supervisor thinks about how the work in my department can be organized to jointly benefit employees and the company. | 1.00 | .30 (.03) |

| 12. My supervisor asks for suggestions to make it easier for employees to balance work and nonwork demands. | 1.04 (.07) | .50 (.05) | |

| 13. My supervisor is creative in reallocating job duties to help my department work better as a team. | 1.16 (.07) | .41 (.05) | |

| 14. My supervisor is able to manage the department as a whole team to enable everyone's needs to be met. | 1.11 (.07) | .34 (.04) | |

| Second-order factor | emotional support | 1.00 | .18 (.03) |

| instrumental support | .99 (.10) | .01 (.02) | |

| role modeling behaviors | 1.18 (.08) | .15 (.03) | |

| creative work-family management | 1.08 (.08) | .07 (.02) |

Supervisor support and supervisor support behaviors

The construct of general supervisor support was measured with a three-item scale (Yoon & Lim, 1999). A sample item is, “My supervisor is willing to listen to my job-related problems.” Reliability for this scale was estimated at .82. Supervisor support behaviors were assessed with a nine-item scale (Shinn et al., 1989). A sample item is, “Switched schedules (hours, overtime hours, vacation) to accommodate my family responsibilities.” Reliability for this scale was estimated at .73. Items were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Work-family conflict

The construct of work-family conflict was measured in two directions (work-to-family and family-to-work) with a total of 10 items (Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, 1996). A sample item is, “The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life.” Reliability for work-to-family conflict was estimated at .87, and at .85 for family-to-work conflict. Items were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Work-family positive spillover

Affective work-family positive spillover was assessed in both directions (work-to-family and family-to-work) with eight items (Hanson, Hammer, & Colton, 2006). A sample item is, “Being in a positive mood at work helps me to be in a positive mood at home.” Reliability of the work-to-family positive spillover scale was .86 and for the family-to-work direction, .92. Items were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Job satisfaction and turnover intentions

Job satisfaction was measured with a five-item scale (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). A sample item is, “Generally speaking, I am very satisfied with this job.” Reliability for this scale was estimated to be .80. Employee intentions to quit their job were measured with a two-item scale (Boroff & Lewin, 1997). A sample item is, “I am seriously considering quitting this company for an alternate employer.” Reliability for this scale was .87.

Analyses

Given the hierarchical data structure (i.e., employees nested within supervisors), all reported statistical analyses employed multilevel models unless otherwise noted. In the assessment of the FSSB factor structure, a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (MLCFA) was conducted with Mplus 4.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2006) using estimation methods that account for item non-response and nonnormality. Because our focus was only the latent structure of associate responses to FSSB items, a saturated latent covariance structure was specified at the supervisor level of the data structure. Given the complexity of MLCFA, we first conducted several suggested preliminary analyses (Grilli & Rampichini, 2007; Heck & Thomas, 2000) to assess whether a multilevel approach was needed and to identify measurement structure problems. For brevity, we only report the important findings from these preliminary analyses. Reliability estimates for the FSSB scores were computed based on the within-supervisor covariance matrix provided by Mplus using the standard formula for computing Cronbach's coefficient alpha based on the number of items and the item variances and covariances (e.g., McDonald, 1999, Eq. 6.28).

Analyses pertaining to evidence of construct, criterion-oriented, and incremental validity were also conducted using Mplus. Convergent validity evidence was based on within-supervisor correlations between scores on the FSSB and scores on the measures of general supervisor support and supervisor supportive behaviors. Criterion-oriented validity evidence was based on multilevel regression analyses predicting important work-family outcomes (i.e., work-family conflict, positive spillover, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions) from FSSB scores. Incremental validity evidence was based on multilevel regression analyses similar to the preceding but also including as predictors the measures of general supervisor support and supervisor supportive behavior, thus controlling for their effects on these outcomes.

Results

Table 3 provides descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and reliability estimates for the variables in this study. For the assessment of statistical significance in the analyses that follow, α = .05 was used as the criterion.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations Among Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB) Overall, Dimensions, and Outcome Variables

| Control Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hours work/week | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Number of children | 0.10 | ||||||||||||||

| FSSB | |||||||||||||||

| 3. FSSB overall scale | − 0.13 | −0.02 | |||||||||||||

| 4. Emotional support | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.86 | ||||||||||||

| 5. Instrumental support | − 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.85 | 0.64 | |||||||||||

| 6. Role modeling | −0.10 | −0.04 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.64 | ||||||||||

| 7. Creative work-family management | − 0.16 | −0.03 | 0.91 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.72 | |||||||||

| General supervisor support | |||||||||||||||

| 8. Supervisor support | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.64 | ||||||||

| 9. Support behaviors | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.56 | |||||||

| Outcome variables | |||||||||||||||

| 10. Work-family conflict | 0.13 | 0.10 | − 0.23 | − 0.17 | − 0.20 | − 0.16 | − 0.24 | − 0.14 | − 0.13 | ||||||

| 11. Family-work conflict | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.38 | |||||

| 12. Work-family positive spillover | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.04 | ||||

| 13. Family-work positive spillover | −0.11 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.53 | |||

| 14. Job satisfaction | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.17 | − 0.37 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.20 | ||

| 15. Turnover intentions | −0.05 | −0.09 | − 0.24 | − 0.20 | − 0.24 | − 0.21 | − 0.21 | − 0.22 | −0.12 | 0.32 | 0.10 | −0.04 | −0.06 | − 0.56 | |

| M 31.71 | 0.74 | 3.51 | 3.48 | 3.67 | 3.46 | 3.49 | 3.90 | 3.29 | 2.59 | 1.90 | 3.88 | 3.90 | 3.49 | 2.35 | |

| SD 8.55 | 1.08 | 0.71 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.88 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 1.11 | |

| Alpha | .94 | .90 | .74 | .86 | .86 | .82 | .73 | .87 | .85 | .80 | .87 |

Note: All FSSB dimensions range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more supportive behaviors. Work-family conflict, positive spillover, job satisfaction, and turnover intention scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater amounts of each construct. Ns range from 358 to 360. All correlations greater than .12 in absolute value are significant at the alpha = .05 level.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

Preliminary analyses to the MLCFA were based on (a) exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses ignoring the data nesting structure to identify potential problems in the measurement structure and (b) univariate multilevel model analyses for the 18 FSSB items to assess whether the magnitude of associate response dependency on their supervisors necessitated a multilevel approach. The results of the preliminary factor analyses suggested that four items did not correlate well with the other items within their FSSB dimensions and the factors representing those dimensions. Inspection of these four item stems suggested a lack of conceptual clarity in these items. Therefore, the analyses that follow involve only the remaining 14 of the 18 FSSB items (see Table 2). No other problems were detected. The results of the preliminary univariate multilevel analyses indicated that most of the remaining 14 items exhibited significant variance in item responses across supervisors with intraclass correlations (ICCs) ranging from .01 to .13 (Mdn = .10). These results suggest that this dependency should not be ignored even though some items exhibited small ICCs.

The MLCFA specified a second-order factor model where the four first-order factors loaded onto a single second-order factor to test whether the associations among the four dimensions are explained by a single second-order factor. Items were specified to load only onto their respective FSSB dimension factor and all error variances were specified as uncorrelated. This second-order confirmatory factor analysis model fit the data well, χ2(178, N = 360) = 294.92, p < .001, comparative fit index = .97, root mean square error of approximation = .04, standardized root mean square residual = .05. Table 2 provides the factor loadings and error variance (along with their standard errors) estimated from this model. All factor loadings for the first-order and second-order factors were statistically significant as were all of the error variances except for the instrumental support first-order factor, which was positive but nonsignificant (p = .71). The standardized factor loadings for the second-order factor were strong, ranging from .82 for the emotional support factor to .99 for the instrumental support factor. Thus, the second-order multilevel factor structure fit the data well, which supports the use of a single total scale score to represent the four FSSB subordinate dimensions.

FSSB Reliability

The reliability estimate for the total FSSB score was .94, exceeding levels deemed acceptable for use in research (cf. Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Reliability estimates were .90, .73, .86, and .86 for the emotional support, instrumental support, role modeling behaviors, and creative work-family management scales, respectively.

FSSB Validity

Convergent validity

To provide evidence of convergent validity, scale scores for the overall FSSB measure were correlated with scores on Yoon and Lim's (1999) measure of general supervisor support and the Shinn et al. (1989) measure of supervisor support behaviors. As displayed in Table 3, FSSB scores correlated positively and significantly with these two measures (i.e., r = .74 and r = .68, respectively). The magnitudes of these correlations suggest a strong conceptual overlap in these construct subdimensions and, therefore, provide evidence of convergent validity.

Criterion-related validity

To provide evidence of criterion-related validity, FSSB scores were used as predictors of six important work-family and job outcomes (i.e., work-family conflict, family-work conflict, work-family positive spillover, family-work positive spillover, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions). In these multilevel regression models, the number of hours worked and the number of children living at home were included as control variables, given their potential effect on these outcomes. FSSB was significantly and negatively related to work-family conflict [β = −.31, 95% CI(−.44, −.19)] and turnover intentions [β = −.46, 95% CI(−.62, −.30)] and positively related to work-family positive spillover [β = .10, 95% CI(.01, .19)], family-work positive spillover [β = .19, 95% CI(.10, .28)], and job satisfaction [β = .42, 95% CI(.33, .51)], but FSSB was not significantly related to family-work conflict [β = −.01, 95% CI(−.10, .07)]. Thus, FSSB scores have significant criterion validity with respect to three of these four important outcomes.

Incremental validity

It is important to assess whether FSSB scores have significant incremental validity in the prediction of work-family and job outcomes over and above existing measures of supervisor support. Toward this aim, FSSB scores were used as predictors of work-family conflict, family-work conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions using multilevel random intercepts-only regression models for the associate level data nested within supervisors. In these multilevel regression models, scores from measures of general supervisor support (Yoon & Lim, 1999) and supervisor support behaviors (Shinn et al., 1989) were used as control variables in addition to the number of hours worked and the number of children. Controlling for these variables, FSSB scores were significantly and negatively related to work-family conflict [β = −.37, 95% CI(−.60, −.15)] and turnover intentions [β = −.45, 95% CI(−.72, −.18)], significantly and positively related to job satisfaction [β = .44, 95% CI(.29, .59)], but not significantly related to family-work conflict [β = −.01, 95% CI(−.10, .07)], work-family positive spillover [β = .10, 95% CI(.01, .19)], and family-work positive spillover [β = .19, 95% CI(.10, .28)]. Thus, FSSB scores have significant incremental validity in the prediction of work-family conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions when controlling for scores on the two existing measures of supervisor support, hours worked, and number of children living at home.

Discussion

Building on the work of Hammer et al. (2007) and Kossek et al. (2007), we developed and validated the multidimensional construct of FSSB. We conceptualized FSSB as hierarchically structured with four subordinate dimensions (Edwards, 2001). These extend traditional emotional support and instrumental support dimensions typically found in general supervisor support measures and introduce role modeling behaviors and creative work-family management dimensions. We partialled out unique variance due to supervisors in employee reports of FSSB by conducting MLCFAs and provided construct, criterion-related, and incremental validity evidence. FSSB demonstrated incremental validity over and above general measures of supervisor support not only in predicting work-family related outcomes but also in predicting more general outcomes such as job satisfaction and turnover intentions.

Our FSSB measure contributes to research and practice in the following ways. First, we show that FSSB is a distinct construct from general supervisor support. Supervisors can be supportive of employees doing their job and not necessarily supportive of family. FSSB assesses employee perceptions of supervisors' behavioral support for integrating work and family. Further research on how supervisor support links to work-family conflict and other job outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction, turnover) should include both general supervisor support measures and FSSB, as they are distinct constructs with differential prediction.

Second, our study fills an important practice gap by helping managers clarify what behaviors are seen as family supportive, thereby reducing ambiguity about how to implement family support. Effective policies and practices that address work-family issues and the changing needs and demographics of the work force are still relatively new in organizations. Managers and employers need tangible examples of how they can change supervision and cultures to meet the changing needs of the workforce. Our measure helps begin this path toward changing organizations in terms of specific supervisor behaviors that provide more family supportive interactions with employees. Training and leadership development could incorporate the FSSB in measurement and feedback. Furthermore, our measure can be used in managerial practices and the development of interventions for organizational change. Change efforts can be designed that build on increasing supervisors' understanding of how family support relates to general support. Behaviors and incentives can be put into place to increase supervisor motivation to show these behaviors. Many workplaces have not been as successful as they would like in increasing supervisor support for family (Kossek, 2006).

Third, our measure attempts to specifically focus on supervisor support independent of organizational level work-family climate and culture. Some prior measures have confounded these two concepts (cf. Thompson et al., 1999). Our measure will help studies to better assess support for family at the direct supervisor level and be able to differentiate this support from more general organizational level work-family culture. Researchers will now be better able to understand whether supervisor support for family is an antecedent, outcome, or subcomponent of work-family culture.

Finally, our measure, by focusing on supervisors, allows researchers to be able to validate the importance of supervisor support as a unique construct beyond the adoption of formal policies, in relation or organizational level culture. Adoption of policies is a necessary but insufficient condition to reduce work-family conflict. It is not the policy alone that matters on paper, but it is the way managers manage the borders of the policies in the departments that matters most in ensuring employee well-being. Formal work-family supports and policies are not always available or feasible (Kelly et al., 2008); thus, there is a need to develop informal supports such as supervisor support for family. We can use our measure to better bridge understanding of formal and informal practices in organizations.

Further Research

Future studies are needed that replicate our multidimensional, multilevel FSSB measure in a variety of contexts across occupations and cultures. Helping solve an hourly worker's work-family conflicts, such as working excessive overtime, is very different from a supervisor alleviating those of a professional teleworker who has problems managing child care in the home. Further research needs to cross-validate the measure using different occupational samples within the United States. Likewise, cross-validation is needed using different national samples, given the differing values that cultures may place on the role of culture and hierarchy in solving work-family conflicts. Further research should also examine a broader array of outcomes of FSSB (e.g., worker health and well-being) and predictors that help us understand what supervisory characteristics and behaviors are related to higher levels of employee-reported FSSB. Furthermore, given that our second-order FSSB factor was strongly correlated with the first-order factor of instrumental support, we may not be able to distinguish these two empirically. Thus, we suggest that further research continue to work on identifying other subordinate dimensions of FSSB that may help to alleviate this problem. Finally, further research should focus on the development and evaluation of organizational interventions and training programs that are based on the FSSB subordinate constructs of emotional support, instrumental support, role modeling behaviors, and creative work-life management.

Understanding how to increase these supervisory behaviors in organizations will help close the gap between existing rhetoric on employer support for work and family and the fact that many employees of all backgrounds and generations are experiencing more tensions between work and family life (Kossek & Distelberg, 2009).

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by the Work, Family and Health Network, which is funded by a cooperative agreement through the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant Nos. U01HD051217, U01HD051218, U01HD051256, U01HD051276), National Institute on Aging (Grant No. U01AG027669), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Grant No. U010H008788). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of these institutes and offices. Special acknowledgment goes to Extramural Staff Science Collaborator Rosalind Berkowitz King, PhD (NICHD), and Lynne Casper, PhD (now of the University of Southern California), for design of the original Workplace, Family, Health and Well-Being Network Initiative. Persons interested in learning more about the network should go to http://www.kpchr.org/workplacenetwork/.

References

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Dorsey Press; Chicago: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Allen MJ, Yen WM. Introduction to measurement theory. Waveland Press; Prospect Heights, IL: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Allen TD. Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2001;58:414–435. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SE, Coffey BS, Byerly RT. Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: Links to work-family conflict and job-related outcomes. Journal of Management. 2002;28(6):787–810. [Google Scholar]

- Bailyn L. Academic careers and gender equity: Lessons learned from MIT. Gender, Work & Organization. 2003;10(2):137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bailyn L, Fletcher JK, Kolb D. Unexpected connections: Considering employees' personal lives can revitalize your business. Sloan Management Review. 1997;38(4):11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bailyn L, Harrington M. Redesigning work for work-family integration. Community, Work & Family. 2004;7(2):197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Beehr TA, Farmer SJ, Glazer S, Gudanowski DM, Nair VN. The enigma of social support and occupational stress: Source congruence and gender role effects. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2003;8:220–231. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.8.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behson SJ. The relative contribution of formal and informal organizational work-family support. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2005;66(3):487–500. [Google Scholar]

- Boroff K, Lewin D. Loyalty, voice, and intent to exit a union: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 1997;51:50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan RD, Cobb S, French JR, Harrison RV, Pinneau SR. Job demands and worker health. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Clark SC. Work cultures and work/family balance. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2001;58:348–365. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook C, Heath F, Thompson RL. A meta-analysis of response rates in Web- or Internet-based surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2000;60(6):821–836. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JR. Multidimensional constructs in organizational behavior research: An integrative analytical framework. Organizational Research Methods. 2001;4:144–192. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R, Stinglhamber F, Vandenberghe C, Sucharski IL, Rhoades L. Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87(3):565–573. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez JP. Child care and corporate productivity: Resolving family/work conflicts. Lexington Books; Lexington, MA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper LM. Relation of work-family conflict to health outcomes: A four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 1997;70:325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Frone MR, Yardley JK, Markel KS. Developing and testing an integrative model of the work-family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1997;50:145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Frye N, Breaugh JA. Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and satisfaction: A test of a conceptual model. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2004;19(2):197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky E, Hughes D, Shinn MB. The corporate work and family life study. Bank Street College of Education; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Glass J, Fujimoto T. Employer characteristics and the provision of family responsive policies. Work and Occupations. 1995;22:380–411. [Google Scholar]

- Goff SJ, Mount MK, Jamison RL. Employer supported childcare, work/family conflict and absenteeism: A field study. Personnel Psychology. 1990;43:793–809. [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein JD. Institutional pressures and strategic responsiveness: Employer involvement in work-family issues. Academy of Management Journal. 1994;37(2):350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus JH, Singh R. Mentoring and the work-family interface. In: Ragins BR, Kram KE, editors. Handbook of mentoring at work. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2007. pp. 519–544. [Google Scholar]

- Grilli L, Rampichini C. Multilevel factor models for ordinal variables. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Work redesign. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Zimmerman K, Daniels R. Clarifying the construct of family supportive supervisory behaviors: A multilevel perspective. Research in Occupational Stress and Well-Being. 2007;6:171–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GC, Hammer LB, Colton CL. Development and validation of a multidimensional scale of perceived work-family positive spillover. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11(3):249–265. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck RH, Thomas SL. Multilevel factor analysis. In: Heck RH, Thomas SL, editors. An introduction to multilevel modeling. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 112–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins K. Supervisor support and work-life integration: A social identity perspective. In: Kossek EE, editor. Work and life integration: Organizational, cultural, and individual perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 445–467. [Google Scholar]

- House JS. Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram P, Simons T. Institutional and resource dependence determinants of responsiveness to work-family issues. Academy of Management Journal. 1995;38(5):1466–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL. Work-family policies: The United States in international perspective. In: Pitt-Catsouphes M, Kossek EE, Sweet S, editors. The work and family handbook: Multi-disciplinary perspectives and approaches. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 99–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Dobbin F. Civil rights law at work: Sex discrimination and the rise of maternity leave policies. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;105:455–492. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly E, Kossek E, Hammer L, Durham M, Bray J, Chermack K, et al. Getting there from here: Research on the effects of work-family initiatives on work-family conflict and business outcomes. The Academy of Management Annals. 2008;2(1):305–349. doi: 10.1080/19416520802211610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby EL, Krone KJ. “The policy exists but you can't really use it”: Communication and the structuration of work-family policies. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2002;30(1):50–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb DM, Merrill-Sands D, Burke R. Waiting for outcomes: Anchoring a dual agenda for change to cultural assumptions. Women in Management Review. 1999;14(5):194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE. Work and family in America: Growing tensions between employment policy and a changing workforce. In: Lawler E, O'Toole J, editors. America at work: Choices and challenges. Palgrave Macmillan; New York: 2006. pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek E, Distelberg B. Work and family employment policy for a transformed work force: Curren trends and themes. In: Crouter A, Booth A, editors. Work-life policies. Urban Institute Press; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Lambert S. Work-family scholarship: Voice and context. In: Kossek EE, Lambert S, editors. Work and life integration: Organizational, cultural and individual perspectives. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Nichol V. The effects of on-site child care on employee attitudes and performance. Personnel Psychology. 1992;45:485–509. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek E, Pichler S, Hammer L, Bodner T. Contextualizing workplace supports for family: An integrative meta-analysis of direct and moderating linkages to work-family conflict. National Meetings of the Society of Industrial & Organizational Psychology; New York. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre LM, Allen TD. Work-supportive family, family-supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: Implications for work-family conflict and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11(2):169–181. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R. Test theory: A unified approach. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Milliken FJ, Martins LL, Morgan H. Explaining organizational responsiveness to work-family issues: The role of human resource executives as issue interpreters. Academy of Management Journal. 1998;41(5):580–592. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. MPlus (Version 4.2) Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2006. Computer software. [Google Scholar]

- Neal MB, Hammer LB. Working couples caring for children and aging parents: Effects on work and well-being. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1996;81(4):400–410. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J, Bernstein I. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll MP, Poelmans S, Spector PE, Kalliath T, Allen TD, Cooper CL, et al. Family-responsive interventions, perceived organizational and supervisor support, work-family conflict, and psychological strain. International Journal of Stress Management. 2003;210(4):326–344. [Google Scholar]

- Osterman P. Work-family programs and the employment relationship. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1995;40:681–700. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport R, Bailyn L, Fletcher JK, Pruitt BH. Beyond work-family balance: Advancing gender equity and workplace performance. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rayman PM, Bailyn L, Dickert J, Carré F, Harvey MA, Krim R, et al. Designing organizational solutions to integrate work and life. Women in Management Review. 1999;14:164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Regan M. Beware the work/family culture shock. Personnel Journal. 1994;73(1):35. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney JA, Gottlieb BH. Development and initial validation of a measure of supportive and unsupportive managerial behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2007;7:186–203. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Wong NW, Simko PA, Ortiz-Torres B. Promoting well-being of working parents: Coping, social support, and flexible schedules. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17:31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LT, Ganster DC. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1995;80(1):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CA, Beauvais LL, Lyness KS. When work-family benefits are not enough: The influence of work-family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1999;54:392–415. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CA, Prottas D. Relationships among organizational family support, job autonomy, perceived control, and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2005;11(1):100–118. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz CF, Strickland OL, Lenz ER. Measurement in nursing and health research. Springer; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Warren J, Johnson P. The impact of workplace support on work-family role strain. Family Relations. 1995;44:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Winfield I, Rushing B. Bridging the border between work and family: The effects of supervisor-employee similarity. Sociological Inquiry. 2005;75(1):55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J, Lim J. Organizational support in the workplace: The case of Korean hospital employees. Human Relations. 1999;82:923–945. [Google Scholar]