There is anecdotal evidence that general practitioners are being flooded with guidelines. We set out to quantify this by conducting a survey of all guidelines retained in general practices in the Cambridge and Huntingdon Health Authority.

Methods and results

FP visited 22 urban and rural general practices, a sample of the 65 practices in the authority, and asked them to produce copies of all guidelines retained for use. Guidelines were defined as any written material used by a doctor or nurse in primary care to assist decision making in relation to health care,1 excluding medical textbooks and electronic databases.

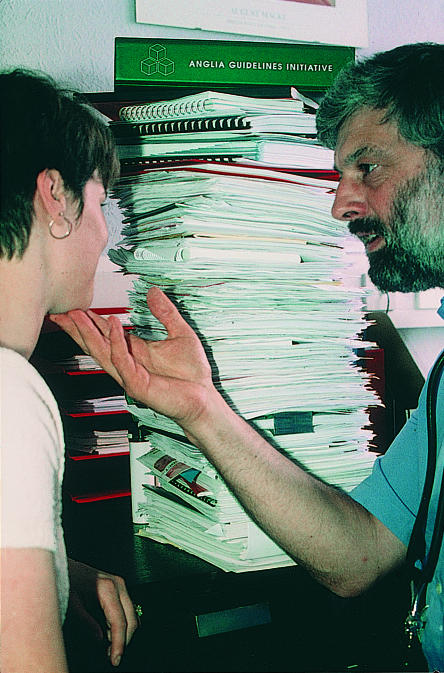

We found 855 different guidelines—a pile 68 cm high weighing 28 kg (see fig). There were 243 single page and 195 two page guidelines. There were, however, 160 guidelines that were more than 10 pages long, including 25 presented as booklets or large folders. About 60% of the guidelines had been produced locally, of which 50% had been produced by local trusts and 30% by general practitioners. The remaining 40% were produced nationally. The pharmaceutical industry and the local health authority produced only 31 (4%) and 32 (4%) of the guidelines respectively.

We found that 38% of all the guidelines collected were undated. The dated guidelines suggest an exponential rise in guideline production since 1989: eight guidelines were published in 1990, compared with 73 in 1995 and 138 in 1996. We identified 57 guidelines produced in the first third of 1997 alone.

Guidelines on clinical or disease management accounted for 75% of the total. Half of the remaining guidelines related to referral pathways. Guidelines produced in general practice were almost exclusively clinical, whereas nearly half of those produced by trusts described referral pathways.

Comment

General practitioners manage 90% of presenting problems without referral elsewhere,2 and they require information to help manage difficult or complex decisions. The mass of paper we collected represents a large amount of information, but it is in an unmanageable form that does little to aid decision making. Information must not be hidden in a load of paper but should be readily accessible and easy to use.

Furthermore, our survey suggests that this unmanageable mass of paper is growing at an ever increasing rate. This exponential rise could be explained by efficient culling of older guidelines, but we consider this to be unlikely. An incidence survey to complement our prevalence survey would clarify this.

Guidelines have been shown to change clinical practice and improve patient outcome.3 This achievement, however, relies on various factors including the scientific validity of the guidelines and a dissemination strategy that promotes compliance.4 The issue of accrediting or “kite marking” guidelines for general practice for relevance, validity (evidence base), and usefulness is essential but potentially inefficient. It could be made much easier by requiring that guidelines state explicitly the evidence base from which they were drawn and their author, sponsor, date of production, and date for review. This would leave users free to draw their own conclusions.

The issue of making information easily accessible and usable at the point of clinical contact indicates an electronic medium. This medium is well suited to being searched, updated, and copied. We are currently exploring this option locally.5 Any electronic method of dissemination will require careful management and will in itself only be a further tool to aid decision making.

Figure.

Pile of 855 guidelines in general practices in the Cambridge and Huntingdon Health Authority

Editorial by Muir Gray

Footnotes

Funding: Cambridge and Huntingdon Health Authority.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Guidelines for clinical practice. From development to use. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fry J. General practice: the facts. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimshaw J, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317–1322. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92244-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Effective Health Care. Implementing clinical practice guidelines: can guidelines be used to improve clinical practice? Leeds: Nuffield Institute for Health, University of Leeds; College for Health Economics and the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; Research Unit, Royal College of Physicians; 1994. (Bulletin No 8.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.WAX home page. Medical Informatics Unit, University of Cambridge. URL: http://www.medinfo.cam.ac.uk/wax.