Abstract

Apicomplexan protozoan parasites have complex life cycles that involve phases of asexual and sexual reproduction. Some genera have intermediate insect hosts, for example, Plasmodium spp. (the cause of malaria), but related genera such as Eimeria spp. (causative agents of coccidiosis in poultry) have a direct life cycle occurring in only a single host. Mechanisms that regulate the life cycles of apicomplexan parasites are unknown, but the intracellular growth of avian Eimeria spp. is easily shortened by serial selection for the first parasites to complete the transition from asexual to sexual reproduction (to yield so-called precocious lines). To investigate the genetic basis of such an abbreviated life cycle, we have used the species E. tenella and analyzed the inheritance of 443 polymorphic DNA markers in 22 recombinant cloned progeny derived from a cross between parents that had selectable phenotypes of precocious development or resistance to an anticoccidial drug. The markers were placed in 16 linkage groups (which defined 12 chromosomes) and a further 57 unlinked groups. Two linkage groups showed an association (P = .0105) with the traits of precocious development or drug-resistance and were mapped to chromosome 2 (ca 1.2 Mbp) and chromosome 1 (ca 1.0 Mbp), respectively. The map provides a framework for further studies on the identification of genetic loci implicated in the regulation of the life cycle of an important protozoan parasite and a representative of a major taxonomic group.

[A table with the segregation data is available as an online supplement at http://www.genome.org.]

Eimeria spp. are obligate, intracellular protozoan parasites, placed within the phylum Apicomplexa and closely related to Plasmodium spp. (the causative agents of malaria) and the zoonotic parasites Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidium spp. E. tenella develops within epithelial cells that line the intestinal tract of domestic fowl and probably infects most of the 30 billion chickens reared annually for meat worldwide. Clinical disease (caecal coccidiosis) is diagnosed often.

In common with other apicomplexan parasites, E. tenella is characterized by an endogenous developmental life cycle that comprises sequential phases of asexual reproduction followed by a terminal phase of sexual reproduction in which gametes fuse to produce a transient diploid nucleus (a zygote) that gives rise to haploid sporozoites. (For E. tenella, eight sporozoites are contained within a cystic transmission form—the oocyst.) Each fertilization event may involve gametes from the same parental population (self-fertilization) or gametes from genetically different populations (cross-fertilization). The sexual phase of the life cycle thus provides an experimental opportunity to establish a genetic linkage map as a prelude to the positional cloning of genetic loci responsible for phenotypic traits of interest.

The life cycles of Eimeria spp., unlike those of some other apicomplexan parasites, are direct and involve only a single host. Each new generation of oocysts is discharged in the feces and these can be collected easily at specific times throughout the patent period of ∼6 d. Serial selection for the first oocysts to appear during the patent period has consistently resulted in the appearance of novel lines characterized by life cycles significantly faster than those of their parents (e.g., Jeffers 1975; McDonald and Ballingall 1983; Shirley and Bellatti 1988). In these so-called precocious lines, the terminal asexual stages are deleted or substantially depleted and the gametes are formed from asexual stages that, in wild-type strains, would differentiate into one or two further serial asexual generations. The trait for more rapid completion of the life cycle has been shown to be genetically stable and inheritable (Jeffers 1976; Sutton et al. 1986).

Because the progression of asexual stages into further rounds of asexual development or the initiation of gametogony are mutually exclusive events, precocious lines of Eimeria spp. provide a unique introduction to studies of the regulation of the apicomplexan life cycle. In this paper we describe genetic linkage analyses of the genome of E. tenella and the inheritance of polymorphic DNA markers into 22 cloned populations. These clones are derived from a genetic cross between two parents defined by the complementary and selectable phenotypes of precocious development and resistance to an anticoccidial drug (arprinocid; Merck Research Laboratories). We chose, as one parent for the genetic cross, a precocious line of E. tenella that completes its life cycle ∼18 h faster than its parent and is characterized by reduced asexual multiplication before gametogony (Jeffers 1975).

RESULTS

In a three-step process we first recovered oocysts from a genetic cross; second, derived recombinant progeny that survived subsequent passage in the presence of the two selection pressures (resistance to arprinocid to a level of 150 ppm and early completion of the life cycle with recovery of oocysts at 117 h postinfection); and third, established 22 cloned lines from infections with single sporocysts (Shirley and Harvey 1996a,b).

All clones were characterized by mature second-generation asexual stages (90–96 h after infection) of the smaller size typical of those of the parent precocious WisF125 line (data not shown).

Identification of Polymorphic Markers

As expected, each clone possessed a combination of DNA markers that defined the parent strains and none was found to have inherited all of the markers from one parent only. Information of the segregation data, primers used, and markers derived are available at http://www.iah.bbsrc.ac.uk/eimeria.

The amplified-fragment-length polymorphism (AFLP) technique was used to derive the greatest number of polymorphic markers, and different combinations of selective primers were used with varying degrees of success. Sixty-four E + 2/M + 3 combinations of primers that comprised 8 E + 2 and 8 M + 3 primers (GIBCO BRL) identified between 0 and 2 polymorphic fragments per gel, whereas the E + 1 and M + 2 primer combinations yielded up to 10 polymorphic fragments per gel. In total >8600 detectable fragments were amplified by AFLP, of which 379 were polymorphic (ca 4.4%).

Polymorphic markers derived by random amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR (RAPD PCR) were also identified, and some were mapped by hybridization to chromosomes separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), thus facilitating the assignment of most large linkage groups to individual chromosomes (see below).

Some large restriction fragments revealed after digestion of chromosomal DNA with BglI, EcoRI, NotI, SfiI, or SmaI and separated by PFGE were also polymorphic and mapped. For example, a 400-kb polymorphic fragment comprising tandem repeats of a 5S ribosomal DNA gene unit (coded etc1 and part of linkage group 10) hybridized to chromosome 10, and an SfiI fragment of about 410 kb (coded etc8 and part of linkage group 12) mapped to chromosome 12.

With only two exceptions, each radiolabelled probe revealed a single allele. Most notably, a chromosome 1-specific probe derived by RAPD-PCR hybridized to two SfiI polymorphic fragments (markers coded etc11 and etc12) that segregated independently in the progeny of the cross and defined linkage groups 1 and 2. Good separation of the four smallest (1–4) and the four largest (11–14) chromosomes was achieved by PFGE (Shirley 1994), and the inheritance of whole chromosomes characterized by clear-size polymorphisms (chromosomes 3, 4, and 11) was also used alone or in conjunction with hybridization studies to assign some linkage groups with their chromosomes.

Linkage Analyses

The complete genetic map should comprise ∼14 linkage groups, consistent with the estimated number of haploid chromosomes in the molecular karyotype, as revealed by PFGE and intensity of staining with ethidium bromide (Shirley 1994). However, because chromosomes 5 and 6 and chromosomes 7 and 8 run close to each other and complete separation is not achieved consistently, two linkage groups that hybridized to these bands were assigned to chromosome 5 or 6 and to chromosome 7 or 8 in the absence of a definitive identification (see Discussion).

Taking a minimum LOD score of 3.0 (probability of linkage is 1000:1), 70.1% of the 443 markers were assigned to 16 linkage groups that defined 12 chromosomes numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6, 7 or 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14. A further 57 linkage groups each comprising 1–11 markers were unassigned (data not shown). A minimum LOD score of 1.5 resulted in only a small increase in the assignment of markers to specific chromosomes (73% of markers to the 16 linkage groups).

The common chromosomal origin of linkage groups 1 and 2 (with chromosome 1) and linkage groups 3 and 4 (with chromosome 2), which is not evident from consideration of LOD scores alone, was established by restriction-fragment-length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses by using chromosome-specific probes, or by using Southern blotting and hybridization of probes representative of the linkage groups on to molecular karyotypes, or by using both. For most groups of markers, no assignment to a chromosome was attempted and the biggest of the 57 unlinked groups (1 and 2) are therefore candidates to define the two remaining “missing” chromosomes (5 or 6, and 7 or 8).

Three linkage groups were characterized by a disproportionate number of markers (Table 1) such that groups 4 (chromosome 2), 11 (chromosome 11), and 15 (chromosome 13) comprised ∼13%, 25%, and 15%, respectively, of all polymorphic fragments scored.

Table 1.

Recombination Within, and Frequency of Markers Identified from, Chromosomes in the Wis Strain of Eimeria tenella

| Chromosome no. | Linkage groups | Approximate size (megabase pairs of DNA) | No. crossovers in 22 progeny | Percentage of markers identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 2 | 1.05 | 12 | 1.4 |

| 2 | 3, 4 | 1.20 | 13 | 13.2 |

| 3 | 5 | 2.0 | 17 | 2.9 |

| 4 | 6 | 2.2 | 3 | 0.5 |

| 5 or 6 | 7 | 3/3.5 | 7 | 2.0 |

| 7 or 8 | 8 | 3.5 | 0 | 1.6 |

| 9 | 9 | 4.5 | 6 | 1.6 |

| 10 | 10 | 4.5 | 10 | 1.6 |

| 11 | 11 | 5 | 33 | 25.0 |

| 12 | 12, 13, 14 | 5.5 | 19 | 2.0 |

| 13 | 15 | >6 | 15 | 15.1 |

| 14 | 16 | >6 | 4 | 2.9 |

| Unlinked groups | 1–57 | 30.6 |

All polymorphic markers were inherited from the parent lines in a ratio not significantly different from the expected 1:1, except for those in linkage groups 2 (chromosome 1) and 4 (chromosome 2) that showed a bias toward the Wey drug-resistant line and WisF125 precocious line, respectively (P = .0105).

DISCUSSION

A characteristic feature of protozoa belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa is a life cycle comprising an expansive phase of asexual reproduction that is followed by the appearance of gametes in the same (e.g., Eimeria spp. and Cryptosporidium) or different host (e.g., Plasmodium, Sarcocystis, Toxoplasma). At a point in the endogenous life cycle that remains to be determined, each parasite commits first, to sexual reproduction and second, to differentiation into morphologically distinct gametocytes, commonly referred to as male and female. The molecular basis of these processes is not known, but because they can occur in clonal populations derived from single haploid asexual forms (e.g., Walliker et al. 1975; Shirley and Millard 1976), an absence of sex chromosomes is implied. Few data are available on the molecular events relating to gametogenesis, although with P. falciparum Vaidya et al. (1995) and Guinet and Wellems (1997) mapped a defect in male gamete production to an 800-kb fragment of chromosome 12; Day et al. (1993) mapped a complete loss of gametocytogenesis to a 0.3-Mb subtelomeric deletion of chromosome 9; and Alano et al. (1995) reported that subclones (with a full-length chromosome 9) of a gametocyte-producing clone (3D7) had lost the ability to produce gametocytes. Similarly, some mutant lines of Toxoplasma also fail to progress to gametogony (Buxton and Innes 1995).

The intact, but abbreviated, life cycle of precocious lines of Eimeria spp. provides an opportunity for the positional cloning of genetic loci that regulate the asexual life cycle and its transition to the sexual phase. The WisF125 precocious line was selected within 10 passages of selection, and the trait was genetically stable when the progeny of a single parasite were subjected subsequently to 25 serial passages without selection (Jeffers 1975). Almost nothing is known about the genetics of the precocious trait (detail of frequency with which it arises, etc.), but the process appears to be stepwise and the general biology of different precocious lines has been reviewed by Shirley and Jeffers (1990) and Shirley and Long (1990).

The second selectable marker chosen for this study was resistance to the anticoccidial drug arprinocid. This drug is metabolized in the chicken and excreted primarily as arprinocid-1-N-oxide ( Wang et al. 1979a; Wang and Simashkevich 1980). The mode of action of either of these two compounds is unclear, although it has been suggested that their mechanism may involve cytochrome P-450-mediated microsomal metabolism leading to the destruction of the endoplasmic reticulum and to cell death (Wang et al. 1979b; Wang et al. 1981).

Previous genetic mapping studies done with Plasmodium chabaudi (e.g., Carlton et al. 1998) or P. falciparum (e.g., Walker-Jonah et al. 1992; Su et al. 1999) examined clonal populations derived from the progeny of a cross in the absence of further selection for recombinant parasites; thus individual haploid clones were characterized by parental or nonparental phenotypes. However, in this work with E. tenella we further selected recombinant parasites characterized by both precocious development and drug-resistance to eliminate the unnecessary cloning and propagation of parasites with a parental phenotype. Our derivation of 25 amplified clones (three were subsequently lost) is by far the largest effort of this type with Eimeria spp. yet reported and represents an uppermost number that can reasonably be maintained in the laboratory at any one time. One consequence of the expedient to eliminate all parasites not characterized by both phenotypes is that our analyses did not include recombinant parasites that were partially precocious and/or partially resistant to arprinocid—expected to be present if full expression of each trait were dependent on more than one genetic locus.

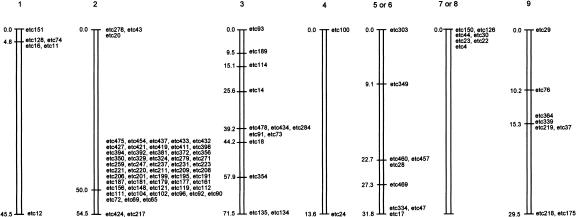

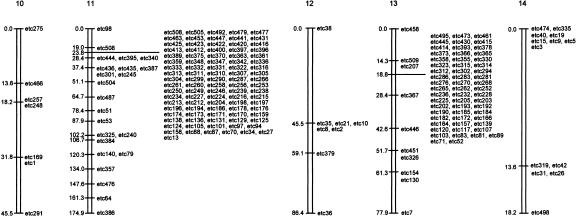

Four hundred forty-three polymorphic DNA markers were identified by several approaches and defined anonymous or known reiterated sequences such as the 5S and 18S ribosomal gene complexes (Shirley 1994). Some large well-separated polymorphic restriction fragments of chromosomal DNA were also identified after PFGE and staining with ethidium bromide (e.g., Bgl1 fragments between 100 kb and 150 kb in size and coded etc3, 4, and 5 and an SfiI fragment coded etc8 of about 400 kb). RAPD-PCR yielded several markers that proved useful for determination of the chromosomal origin of some of the linkage groups that was not apparent from consideration of LOD scores alone (including those that associated with the phenotypes of interest; see the following discussion). AFLP fingerprinting proved to be the most informative mapping strategy. Two primers with a total of five selective bases were used initially and typically yielded about 20–30 radiolabelled fragments (between about 50 bp and 400 bp in size) on each gel, with 0–2 being polymorphic. However, with a total of three selective bases, up to 150 fragments were resolved per gel, of which up to 12 were polymorphic. The smaller number of selective bases is clearly more appropriate for AFLP studies on species of Eimeria that are characterized by genomes of about 50 Mbp in size (Shirley 1994). The loci mapped cover ∼653 cM; linkage maps are shown in Figure 1. The number of crossovers in each chromosome (Table 1) is probably an underestimate because one-third of all markers remain to be assimilated within the linkage map. Eimeria tenella appears to be more similar to P. falciparum, which has a high meiotic crossover activity (Su et al. 1999), than to T. gondii, for which up to only 3 of the 11 chromosomes showed internal recombination in most clones and, moreover, no intrachromosomal crossovers were observed at all in three of 19 recombinant clones (Sibley et al. 1992).

Figure 1.

Genetic linkage maps of chromosomes constructed from inheritance of polymorphic loci. Map distances are given in centiMorgans and the depiction of chromosomes does not take into account differences in their sizes. Chromosomes are numbered in order of increasing size.

Approximately equal numbers of markers derived from the two parents in most linkage groups, although significant segregation disparities (P = .0105) were found in linkage group 4 (chromosome 2) and linkage group 2 (chromosome 1). Up to 17 of the 22 clones in linkage groups 4 and 2 inherited alleles from the precocious or drug-resistant parent, respectively, and these data allow a preliminary assignment of loci for precocious development to chromosome 2 and arprinocid resistance to chromosome 1. Markers most closely linked to the phenotypic traits were etc11, etc16, etc74, and etc128 (linkage group 2) and the 54 markers defined by etc65, etc69, etc72, and etc90 (linkage group 4).

Notwithstanding the relatively large numbers of unlinked groups still to be assigned to specific chromosomes, a high proportion (ca 53%) of all markers defined linkage groups 4 (chromosome 2), 11 (chromosome 11), and 15 (chromosome 13) (Table 1). Furthermore, the greater majority of markers within these three groups were inherited identically. Reasons for this dichotomy of marker inheritance are not known, but selection for only recombinant parasites within the progeny of the cross may account for the presence of the disproportionately large number of polymorphic markers found within linkage group 4. The similar overrepresentation of linkage groups 11 and 15 could reflect differences in the distribution of the restriction sites for the two enzymes used for AFLP analyses, or differences in DNA methylation patterns, or both.

The organization of chromosome 2 in E. tenella is now being examined and, although the positions of the crossovers in chromosome 2 are not known, two of the noninformative markers within linkage group 3 (etc43 and etc20) are NotI fragments that define >320 kb of the chromosome. A new, independent, panel of chromosome 2-specific markers is now being used to further define the remaining 900-kb fragment of the 1.2 Mbp chromosome.

METHODS

Animals, Parasites, and the Genetic Cross

Parasites were maintained by passage in 3–7-wk-old Light Sussex chickens, from the Institute for Animal Health (formerly HPRS) flock, kept free from extraneous coccidial infection. Details of the parasites used and the making of the genetic cross have been described by Shirley and Harvey (1996a). In brief, parasites used were (1) a precocious line, coded WisF125, derived from the Wisconsin laboratory strain (Jeffers 1975) and characterized by the phenotypes of early completion of the life cycle (resulting in oocyst production by 108 h after infection), smaller second-generation schizonts, and sensitivity to the anticoccidial drug arprinocid; and (2) a line selected from the Weybridge (Wey) laboratory strain and characterized by normal development (oocyst production ∼130 h after infection) and resistance to 150 ppm arprinocid.

A cross of E. tenella was made by infecting unmedicated chickens with both the Wey arprinocid-resistant strain and WisF125 (the latter being given 24 h later), and the new oocysts were collected 168 h after inoculation with the Wey arprinocid-resistant strain. Progeny of the cross were passaged in chickens medicated with 150 ppm arprinocid and oocysts were collected at 117 h after infection to obtain adequate numbers of recombinant parasites. Twenty-two cloned lines were established from infections with single sporocysts of the recombinant parasites (Shirley and Harvey 1996b). To aid construction of the linkage groups, we used the notations “A” and “P” to define the origins of the polymorphic markers from the parent Wey arprinocid-resistant line or the Wis F125 precocious line, respectively.

DNA Fingerprinting Analyses

DNA loci showing polymorphisms between the two parent populations and the 22 cloned lines deriving from the cross were identified by using three approaches.

Southern Hybridization of RFLPs

Approximately 20-μL pieces of agarose blocks of chromosomal DNA (∼30 μg/mL) prepared from purified sporozoites (Shirley et al. 1990; Shirley 1994), were digested overnight with 30 units of a restriction endonuclease (GIBCO BRL), as described by Corcoran et al. (1986) and Shirley (1994) by using conditions and 50–100 μL of the buffers recommended by the supplier.

DNA fragments were separated by size by using conventional electrophoresis or by PFGE in which 200-ml gels and 0.5 × TBE buffer were used in combination with (1) 1.2% agarose, 160 volts (v), with pulse times of 20–50 s for 48 h plus 1–5 s for 15 h; or (2) 1.0% agarose, 180 v, with a pulse time of 5–18 s for 24 h. DNA was blotted on to Hybond N (Amersham) and probes were radiolabelled with 32P by using Prime-It II Random Priming Kit (Stratagene) and hybridized to filters for 16–48 h at 65°C (Shirley 1994), except for the inclusion of prehybridization and hybridization buffers described by Church and Gilbert (1984). Filters were washed three times at 65°C in 1 × SSC before exposure to x-ray film at −70°C against intensifying screens. DNA was stripped from some filters by incubation for several hours in water at an initial temperature of 80°C.

DNA probes included repetitive sequences derived from BbvI-restricted chromosomal DNA and cloned into the vector pUC13 (Shirley 1994). 5s rRNA and 18s rRNA gene probes were kindly provided by Mrs. Janene Bumstead and Dr. Fiona Tomley, respectively. Chromosome 1- and 2-specific probes were derived by RAPD-PCR of individual chromosomes (see following). Large, well-separated DNA fragments (200 –500 kb) were revealed by PFGE following digestion of chromosomal DNA with BglI, EcoRI, NotI, SfiI, or SmaI. Cosmids from a library of E. tenella (H) DNA were kindly provided by Drs. Bastiaan Hoogendoorn and Fiona Tomley.

Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA by PCR (RAPD-PCR)

More than 80, 10 mer oligonucleotides containing 70%–80% G + C bases (Genosys and GIBCO BRL) were used individually for RAPD-PCR to identify fragments polymorphic for the Wey and WisF125 parental lines. Informative oligonucleotides were then used to screen the 22 cloned progeny. Conditions of PCR were as described by Shirley and Bumstead (1994) except that 2 μL of molten chromosomal DNA blocks (ca 50 ng DNA) were used. PCR products were separated by size by electrophoresis through 2% agarose gels (GIBCO BRL).

DNA from isolated chromosomes 1 and 2 was also used as a template for RAPD-PCR reactions (see following) and 5-μl aliquots of molten chromosomal DNA were used with random combinations of two 10 mer oligonucleotides. Some of the amplified fragments were separated by size by electrophoresis in low-melt agarose, excised, and used to probe both Southern blots of separated chromosomes and restriction digests of chromosomal DNA to confirm their chromosomal specificity and to identify polymorphisms between the Wey and WisF125 parent lines, respectively.

AFLPs

AFLP analyses were performed as published previously (Meksem et al. 1995; Vos et al. 1995). In brief, DNA for the analyses was extracted from blocks of chromosomal DNA by using standard phenol:chloroform and ethanol precipitation methods (Sambrook et al. 1989) and ∼200 ng was used for each digestion with EcoRI and MseI. The fragments produced were then ligated to EcoRI and MseI adaptors.

The first round of amplification by PCR was performed by using a primer pair based on the sequences of the EcoRI (33P-labelled as described by GIBCO BRL) and MseI adaptors, the latter containing one additional selective nucleotide at the 3′ end (viz. MseI + C).

The second round of amplification by PCR was performed by using combinations of two new primers derived from the sequence of the EcoRI and MseI primers that were (1) supplied with the commercial kit or (2) prepared by ourselves (supplied by MWG-Biotech).

For (1), two additional selective bases were present in each primer (coded E-AA; E-AC; E-AG; E-AT; E-TA; E-TC; E-TG; E-TT and M-CAA; M-CAC; M-CAG; M-CAT; M-CTA; M-CTC; M-CTG or M-CTT, respectively), and for (2) one selective base was included (coded E-A; E-C; E-G; E-T; and M-CA; M-CC; M-CG; M-CT; M-CT; M-CC; M-CG or M-CT, respectively). 33P-labelled amplified fragments were analysed by electrophoresis through a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel to derive the fingerprint.

Coding of Polymorphic Markers

For reference purposes a code, “etcX”, was assigned to each polymorphic marker identified by the three approaches, where “etc” is derived from “e. tenella, compton” and X is a number specific to the marker. (A small number of markers that were assigned a code initially were removed subsequently after further inspection and not replaced.)

Separation of Chromosomes by PFGE

Different conditions were required to separate the E. tenella chromosomes. Chromosomes 1 and 2 (the two smallest) in blocks of chromosomal DNA blocks were separated optimally from the rest by PFGE in 0.75% low-melt agarose (FMC, Sea Plaque) for 66 h at 140 v with a pulse time of 200 sec. Chromosomes 1, 2, 3, and 4 were also resolved by PFGE in a combination of 0.8% chromosomal grade agarose (BioRad) and 0.2% FMC, ME grade agarose at 120 v for 48 h with a pulse time of 270 sec followed by 70 v for 24 h with a pulse time of 1000 sec. Larger chromosomes were separated as described by Shirley (1994). The gels were blotted and probed as described earlier. Examination of the inheritance of some entire chromosomes that were defined by size polymorphisms was also possible following PFGE.

Analyses of Inheritance Data and Construction of Linkage Maps

Inheritance data for each polymorphic marker were analysed by Map Manager QT software (Manly and Cudmore, 1997; Manly, 1998). The dataset was designated as a “Backcross”, and a logarithm (base 10) of an odds ratio (a LOD score) of +3 or greater was used as statistical significant evidence of linkage. In addition, a chi-squared test for goodness of fit against a 1:1 ratio of inheritance was determined for the segregation and independent assortment of each marker.

Histological Analyses of Parasites Developing In Vivo

The endogenous development of each E. tenella clone derived from the cross was examined at 90–96 h postinfection by microscopy of caecal tissue that had been fixed in formal saline and stained with haemotoxylin and eosin.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL shirley@bbsrc.ac.uk; FAX 44-1635-577263.

Article and publication are at www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr149200.

REFERENCES

- Alano P, Roca L, Smith D, Read D, Carter R, Day K. Plasmodium falciparum: Parasites defective in early stages of gametocytogenesis. Exp Parasitol. 1995;81:227–235. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton D, Innes EA. A commercial vaccine for ovine toxoplasmosis. Parasitology. 1995;110:S11–16. doi: 10.1017/s003118200000144x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton J, Mackinnon M, Walliker D. A chloroquine resistance locus in the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;93:57–72. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran LM, Forsyth KP, Bianco AE, Brown GV, Kemp DJ. Chromosome size polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum can involve deletions and are frequent in natural parasite populations. Cell. 1986;44:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day KP, Karamalis F, Thompson J, Barnes DA, Peterson C, Brown H, Brown GV, Kemp DJ. Genes necessary for expression of a virulence determinant and for transmission of Plasmodium falciparum are located on a 0.3-megabase region of chromosome 9. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:8292–8296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinet F, Wellems TE. Physical mapping of a defect in Plasmodium falciparum male gametocytogenesis to an 800 Kb segment of chromosome 12. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;90:343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers TK. Attenuation of Eimeria tenella through selection for precociousness. J Parasitol. 1975;61:1083–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers TK. Genetic recombination of precociousness and anticoccidial drug resistance in Eimeria tenella. Z für Parasitenk. 1976;50:251–255. doi: 10.1007/BF02462970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly, K.F. 1998. User's Manual for Map Manager Classic and Map Manager QT. http://mcbio.med.buffalo.edu/MMM/MMM.html

- Manly KF, Cudmore RH., Jr . Abstracts of the 11th International Mouse Genome Conference, St. Petersburg, FL. 1997. Map Manager QT, Software for mapping quantitative trait loci. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald V, Ballingall S. Further investigation of the pathogenicity, immunogenicity and stability of precocious Eimeria acervulina. Parasitology. 1983;86:361–369. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000050551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meksem K, Leister D, Peleman J, Zabeau M, Salamini F, Gebhardt C. A high-resolution map of the vicinity of the R1 locus on chromosome V of potato based on RFLP and AFLP markers. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;249:74–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00290238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook JF, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW. The genome of Eimeria tenella: Further studies on its molecular organisation. Parasitol Res. 1994;80:366–373. doi: 10.1007/BF00932373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW, Bellatti MA. Live attenuated coccidiosis vaccine: Selection of a second precocious line of Eimeria maxima. Res Vet Sci. 1988;44:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW, Bumstead N. Intra-specific variation within Eimeria tenella detected by the random amplification of polymorphic DNA. Parasitol Res. 1994;80:346–351. doi: 10.1007/BF02351878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW, Harvey DA. Eimeria tenella: Genetic recombination of markers for precocious development and arprinocid resistance. Appl Parasitol. 1996a;37:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW, Harvey DA. Eimeria tenella: Infection with a single sporocyst gives a clonal population. Parasitology. 1996b;112:523–528. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000066099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW, Jeffers TK. Genetics of coccidia and genetic manipulations. In: Long PL, editor. Coccidiosis in man and domestic animals. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW, Long PL. Control of coccidiosis in chickens immunization with live vaccines. In: Long PL, editor. Coccidiosis in man and domestic animals. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW, Millard BJ. Some observations on the sexual differentiation of Eimeria tenella using single sporozoite infections in chicken embryos. Parasitology. 1976;73:337–341. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000047016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW, Kemp DJ, Pallister J, Prowse SJ. A molecular karyotype of Eimeria tenella as revealed by contour-clamped homogeneous electric field gel electrophoresis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;38:169–173. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90020-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley LD, LeBlanc AJ, Pfefferkorn ER, Boothroyd JC. Generation of a restriction fragment length polymorphism linkage map for toxoplasma gondii. Genetics. 1992;132:1003–1015. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.4.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Ferdig MT, Huang Y, Huynh CQ, Liu A, You J, Wootton JC, Wellems TE. A genetic map and recombination parameters of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1999;286:1351–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton CA, Shirley MW, McDonald V. Genetic recombination of markers for precocious development, arprinocid resistance, and isoenzymes of glucose phosphate isomerase in Eimeria acervulina. J Parasitol. 1986;72:965–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya AB, Muratova O, Guinet F, Keister D, Wellems TE, Kaslow DC. A genetic locus on Plasmodium falciparum chromosome 12 linked to a defect in mosquito-infectivity and male gametogenesis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;69:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00199-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, Reijans M, van de Lee T, Hornes M, Frijters A, Pot J, Peleman J, Kuiper M, Zabeau M. AFLP: A new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Jonah A, Dolan SA, Gwadz RW, Panton LJ, Wellems TE. An RFLP map of the Plasmodium falciparum genome, recombination rates and favored linkage groups in a genetic cross. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;51:313–320. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90081-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walliker D, Carter R, Sanderson A. Genetic studies on Plasmodium chabaudi: Recombination between enzyme markers. Parasitology. 1975;70:19–24. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000048824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Simashkevich PM. A comparative study of the biological activities of arprinocid and arprinocid-1-N-oxide. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1980;1:335–345. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(80)90051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Simashkevich PM, Stotish RL. Mode of anticoccidial action of arprinocid. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979a;28:2241–2248. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90685-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Tolman RL, Simashkevich PM, Stotish RL. Arprinocid, an inhibitor of hypoxanthine-guanine transport. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979b;28:2249–2260. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Simashkevich PM, Fan SS. The mechanism of anticoccidial action of arprinocid-1-N-oxide. J Parasitol. 1981;67:137–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]