Abstract

Proteins which bind methylated lysines (“readers” of the histone code) are important components in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression and can also modulate other proteins that contain methyl-lysine such as p53 and Rb. Recognition of methyl-lysine marks by MBT domains leads to compaction of chromatin and a repressed transcriptional state. Antagonists of MBT domains would serve as probes to interrogate the functional role of these proteins and initiate the chemical biology of methyl-lysine readers as a target class. Small molecule MBT antagonists were designed based on the structure of histone peptide-MBT complexes and their interaction with MBT domains determined using a chemiluminescent assay and ITC. The ligands discovered antagonize native histone peptide binding, exhibiting 5-fold stronger binding affinity to L3MBTL1 than its preferred histone peptide. The first co-crystal structure of a small molecule bound to L3MBTL1 was determined and provides new insights into binding requirements for further ligand design.

Introduction

Epigenetic mechanisms are the basis for heritable changes in the utilization of the genome in different cell-types that are not dependent upon changes in the DNA code.1 Epigenetic regulation during development and differentiation permits the specialization of function between cells and enables transient environmental factors to result in a lasting change in cellular and organism behavior.2 Knowledge of the mechanisms and pathways which define the epigenome holds great promise for our understanding of many domains of biology including cancer, cell-fate and pluripotency.3

The substrate for epigenetic control is chromatin – the complex of DNA, RNA and histone proteins that efficiently package the genome in an appropriately accessible form within each cell. The building block of chromatin structure is the nucleosome: an octamer of histone proteins – associated dimers of H3 and H4 capped with dimers of H2A and H2B – around which 147 base pairs of DNA are wound. The amino-terminal tails of histone proteins are unstructured and protrude from the nucleosomes where they are subject to more than 100 posttranslational modifications.4 These modifications are referred to as the histone code and include histone lysine and arginine methylation; lysine acetylation, DNA cytosine methylation and histone sumoylation, ubiquitination, ADP-ribosylation and phosphorylation. These covalent modifications often serve to create docking sites for proteins that directly or indirectly modulate RNA polymerase activity. Among these, the methylation of lysine residues plays a central role through its influence on the activation and repression of gene expression. The enzymatic components of lysine methylation have been targeted for chemical probe and drug discovery and are well documented5 and a recent report has highlighted antagonists of readers of acetyl-lysine.6 However, experimental reports of small molecule inhibitors of methyl-lysine binding proteins, readers of the histone code, are limited.7,8

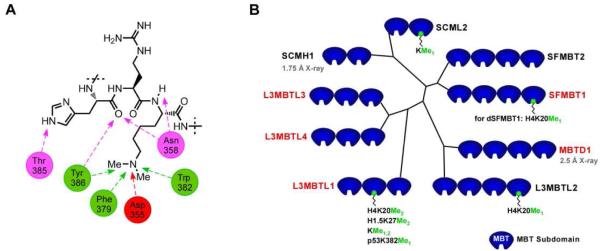

Malignant Brain Tumor (MBT) domains belong to an extended family of methyl-lysine binding proteins which is referred to as the ‘Royal family’, made up of Tudor, Agenet, chromo, PWWP, the WD40 repeat protein and the plant homeodomain (PHD). Current estimates of the number of methyl-lysine binding modules in the human proteome is >170 and there is no doubt that this estimate will grow over time.9 A recent review of the available high-resolution crystal structures of these domains summarizes the key recognition features as an electron-rich aromatic cage binding the methyl-lysine cation with additional charge neutralization and H-bonding to up to two acidic functionalities, depending upon the methylation state of the binder (Figure 1A).10 The ability of this rather subtle chemical modification, which results in no change in charge of the modified residue, to selectively mediate protein-protein interactions that profoundly regulate gene expression is rather remarkable.

Figure 1.

A) Histone peptide showing the methylated lysine and presumed interactions with L3MBTL1 based on the H4K20Me2-L3MBTL1 co-crystal structure. B) Phylogenetic tree of human proteins containing MBT domains; other protein subdomains are omitted for clarity. Protein names in red signifies an assay described in the paper.

MBT domains selectively recognize lower methylation states (KMe1, KMe2) of histone lysine residues and their binding leads to compaction of chromatin and overall repression of gene expression.11 The crystal structures of multiple MBT domains have been solved and reveal few specific interactions beyond the methylated lysine of the histone peptides co-crystallized in these studies12 suggesting that in contrast to PHD fingers, chromo and tudor domains, very little sequence specificity can be anticipated. The lack of sequence specificity for L3MBTL1 is also evident in binding affinities of dye tagged peptides containing mono or dimethyl-lysine determined using fluorescence polarization (FP) assays.12a, 13 For our research aimed at discovery of small molecule MBT ligands, we selected a representative subset of proteins from the MBT family. We chose L3MBTL1, a member of the MBT family having a tandem repeat of three MBT domains, as our primary target based on the availability of structural and biological data.13-14 L3MBTL1 is known to act as a “chromatin lock”14a to repress expression of E2F regulated genes such as the growth related and oncogenic c-myc gene. Recently, L3MBTL1 has also been shown to bind to the tumor suppressor p53 via methylation dependent recognition of lysine 382 and indeed, it has been suggested that repression of c-myc may also be mediated via binding to lysine-methylated retinoblastoma (Rb) protein15 which is methylated by SMYD2.16 Furthermore, depletion of L3MBTL1 has been linked to both DNA breaks, the DNA replication machinery and ultimately genomic instability.17 Therefore, L3MBTL1 appears to be directly implicated in the stability of DNA and the reader functions as both a reader of repressive lysine methylation marks on histones and the methylation status of key regulatory proteins to integrate chromatin availability with the activity and location of these proteins. From a structural biology perspective it is noteworthy that only the second MBT domain of L3MBTL1 has been shown to bind methyl-lysine and the function of the remaining MBT domains is not understood, though it has been suggested that they play a role in recognition of multiple nucleosomes or residues other than methyl-lysine.15 In addition, L3MBTL1 has been shown to be involved in the erythroid differentiation of human hematopoietic progenitor cells.18

To make up our initial methyl-lysine target-class panel we selected homologues of L3MBTL1: L3MBTL319 and L3MBTL420 and to cover the other branches of the phylogenetic tree, SFMBT121 and MBTD1 (Figure 1B).22 To gauge selectivity versus other methyl-lysine binding domains, the PHD finger PHF13 which has been shown to bind di- and trimethylated lysine23 and the chromo domain CBX7 were chosen.24 While this panel of methyl-lysine binding domains only scratches the surface of this large target-class, inclusion of both closely related MBT domains and more distant and structurally diverse binders provides an initial basis to assess both the selectivity of ligands and the tractability of binders for ligand discovery. Several previous publications report modest binding constants (Kd’s in the micromolar range) of various peptides to L3MBTL1 and we anticipated challenges in both assay development and the discovery of potent ligands.

To circumvent this affinity problem, we developed a high-throughput assay suitable for discovery of weak antagonists of peptide binding using an Amplified Luminescent Proximity Homogeneous Assay (AlphaScreen) technology.25 This bead-based chemiluminescent platform is suited for low-affinity interactions as binding is artificially enhanced due to the avidity of the multiple binding sites on each bead. During this research and a subsequent high throughput screen of a 100,000 member diversity library, we were unable to identify tractable hits that retained activity in isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments and we were therefore motivated to focus our efforts on the ligand and structure-based hit discovery effort described here. We have also applied virtual screening to ligand discovery for L3MBTL1 and those results were recently published.7

Results and Discussion

Peptidomimetics

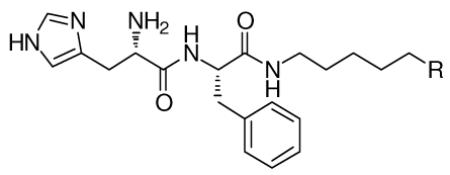

For our initial exploration of antagonists of MBT domains we chose to maintain a peptide-like structure modeled on the published co-crystal structure of H4K20Me2 bound to L3MBTL1.12b Based on the weak binding and lack of specific interactions with native sequences, our design only included two amino-acids: a histidine residue intended to make an interaction with threonine 385 on the protein surface (Figure 1), and for ease of purification a phenylalanine residue in place of arginine. The key methylated lysine residue was replaced with a variety of simple diamines (Table 1) as no interactions with more carboxy terminal portions of H4K20Me1 were anticipated.

Table 1.

Effect of the amine (R) on binding to L3MBTL1 determined by ITC.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | L3MBTL1 Kd (μM)a |

| 1 |

|

No interaction observed |

| 2 |

|

>100 |

| 3 |

|

>100 |

| 4 |

|

No interaction observed |

| 5 |

|

78 ± 9 |

| 6 |

|

37 ± 1 |

Kd values are the average of two independent trials, ± the standard deviation.

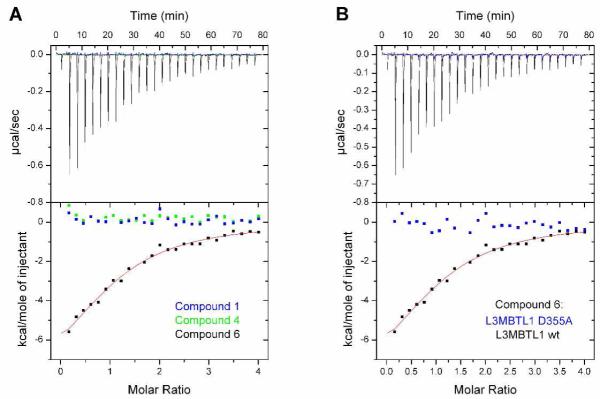

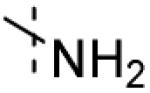

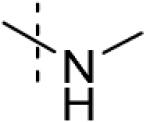

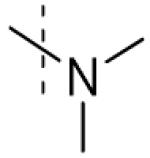

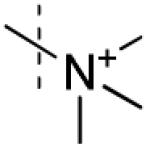

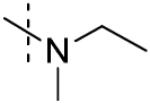

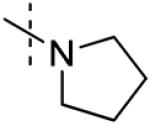

In the AlphaScreen assay both methylethylamine 5 and pyrrolidine 6 (Table 1) had better binding affinities to MBT domains compared to the mono and dimethyl-lysine modifications, however some interference with the assay signal was also noted for these compounds in the previously described counterscreen.25a This interference was also observed with a subset of small-molecule scaffolds. The binding of select antagonists identified in the homogeneous chemiluminescent assay were therefore confirmed using ITC.26 ITC offers a direct and complete characterization of the thermodynamic properties and stoichiometry involved in a bimolecular equilibrium interaction,27 in which the ligand (small molecule) is titrated into the receptor (protein). The obvious disadvantage of ITC is the use of large amounts of protein. Consistent with a specific interaction with the methyl-lysine binding site of L3MBTL1, ITC confirmed the expected effect of lysine methylation state on binding in our antagonists: unmethylated amines and quaternary ammonium species (1 and 4) did not bind while mono- and dimethylated amines 2 and 3 bound weakly (Kd > 100 μM). Pyrrolidine analog 6 showed significantly higher binding affinity relative to the mono- and dimethylated amines. The ITC data also confirmed the 1:1 stoichiometry of binding between all of the peptidomimetics and the MBT domain. To further confirm that the binding of the peptidomimetics occurred at the anticipated site in MBT domain 2 of L3MBTL1, we expressed the D355A mutant of L3MBTL1 in which the critical aspartic acid residue in this binding pocket is replaced by an alanine thereby eliminating the ability to form a salt bridge to the methylated lysine or lysine mimetic.12b, 14a Indeed, no binding was observed between compound 6 and D355A L3MBTL1 by ITC (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

A) Effect of methylation state on binding of 1, 4 and 6 to L3MBTL1. B) ITC binding curves for pyrrolidinyl analog 6 with both wt L3MBTL1 and D355A mutant of L3MBTL1.

Small-Molecule Ligands of MBT Domains

To further explore MBT ligand requirements and based on the seeming lack of influence of neighboring residues in a peptide context, we extended our studies toward nonpeptidic small molecules. We were particularly interested in whether pyrrolidine mimics of the methyl-lysine side chain could provide affinity in the context of simple aromatic anchors with good predicted cell permeability that could easily be modified using standard chemical methods. Such scaffolds could also improve the ligand efficiency significantly.28

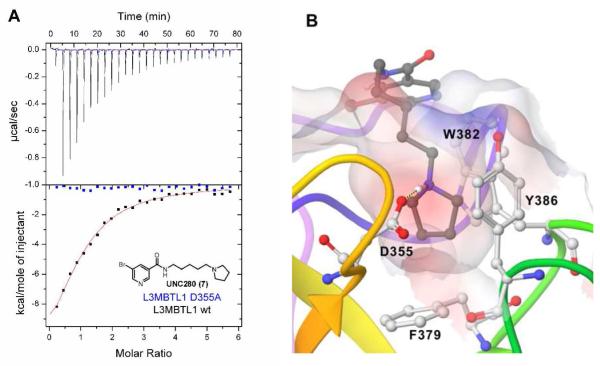

Indeed, simple aromatic anchors with pyrrolidinyl side-chains (7 (UNC280), Figure 3A) interacted with MBT domains in the AlphaScreen without interference in the counterscreen (Table 3).25a Binding was confirmed using ITC for both L3MBTL1 (Table 4) and L3MBTL3 (data not shown). In the context of work with small molecules it was found that the presence of DMSO in ITC experiments abolished all binding and ITC experiments were therefore performed using aqueous buffer for dissolution. The nicotinic acid-based pyrrolidine, 7 binds with a Kd of 26 μM to L3MBTL1 and represents a significant improvement in ligand efficiency28 compared to the native H4K20Me1 9-mer peptide (residues 17-25, Kd = 24 ± 1 μM). The calculated ligand efficiencies for both the 9-mer peptide12b and the small molecule ligand 7 using the pKd data available from ITC assays indicate a 4-fold increase in binding efficiency. For context, we also tested mono- and dimethyl-lysine via ITC and both exhibit binding constants exceeding 250 μM against L3MBTL1.

Figure 3.

A) ITC binding curve of nicotinamide (7) to both wt L3MBTL1 and D355A mutant. B) Docking of 7 to L3MBTL1, illustrating the solvent exposure of aromatic anchor.

Table 3.

Full AlphaScreen IC50-panel for nicotinamides 7 and 14 against 5 MBT domains, one PHD finger and one Chromo domain.

| Compound | L3MBTL1 IC50 (μM)a |

L3MBTL3 IC50 (μM) |

L3MBTL4 IC50 (μM) |

SFMBT IC50 (μM) |

MBTD1 IC50 (μM) |

PHF13 IC50 (μM) |

CBX7 IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

46 ± 20 | 28 ± 4 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | 48 ± 4 | Inactive |

|

6 ± 0.5 | 35 ± 3 | 69 ± 34 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

IC50 values are the average of at least two independent trials, ± the standard deviation.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic binding parameters of nicotinamides 7 and 14 to L3MBTL1 using ITC.

| Compound | Kd μM | ΔH kcal/mol | TΔS kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

26 ± 0.7 | −15 ± 0.4 | −9 ± 0.4 |

|

5 ± 1 | −13 ± 0.6 | −6 ± 0.5 |

Values are the average of at least two independent trials ± the standard deviation.

Our recently reported virtual screen6 of L3MBTL1 also selected a pyrrolidine containing sulfonamide of similar potency to 7 and further optimization was based on both arylsulfonamide and nicotinic acid scaffolds.

In hopes of developing SAR for these scaffolds and enhancing potency, greater than 350 compounds were synthesized and tested in the AlphaScreen format. For example, Suzuki couplings to replace the aryl bromide of 7 with aromatic groups and various aromatic anchors were tested in order to potentially discover a favorable interaction outside the methyl-lysine binding pocket. Unfortunately, the resulting structure-activity relationships (SAR) were flat and demonstrated that for larger substituents any additional enthalpy (ΔH) gain was negated by increasing entropic penalties resulting in diminished overall binding affinity (data not shown).

The most promising results emerged from our study of the effect of the aliphatic sidechain and the nature of the amine. This was anticipated as the most important contributions to binding arise from the insertion of lysine mimetics into the binding cavity and interactions with the aromatic pocket and the acidic residue D355. In the sulfonamide series, β-oxygenated amines either within the aliphatic side chain (8) or the amine (morpholine 9) did not show any activity consistent with the importance of a very basic amine for effective binding to MBT domains (Table 2).

Table 2.

SAR studies of the basicity of the amine and the size of the pyrrolidine.

| Compound | 3MBTL1 Kd (μM)b |

|

|---|---|---|

| 8 |

|

No Binding a |

| 9 |

|

No Binding a |

| 10 |

|

25 ± 8 |

| 11 |

|

>100 |

| 12 |

|

No Binding

Interaction |

| 13 |

|

51 ± 9 |

No binding by AlphaScreen.

Kd values are obtained from single experiments, standard deviations result from least square curve fitting.

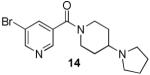

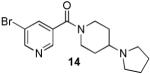

Analogues with methylation of the 2- and 3-position of the pyrrolidine (11 and 12) weaken the binding affinity significantly whereas a 3-methyl group abolishes all binding. However, fluorination at the 3-position of the pyrrolidine is permitted (2-fold weaker). Further study of the aliphatic linker did not reveal any effect of the length of the chain, however, most restricted, bulky or aromatic linkers failed to bind to the selected MBT domains. An exception was 14 (UNC669) which exhibited a promising 6 μM binding affinity in the chemiluminescent assay.

The results of profiling conformationally less constrained 7 and more constrained 14 versus our panel of methyl-lysine binding domains are summarized in Table 3. Whereas 7 shows weak binding in the AlphaScreen against L3MBTL1, L3MBTL3 and PHF13, 14 is 5-fold selective for L3MBTL1 over L3MBTL3, 10-fold selective over L3MBTL4 and does not interact with the other domains.

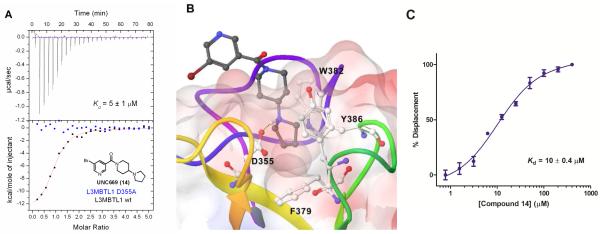

Based on promising results in the chemiluminescent assay, 14 was selected for ITC experiments and strong binding to L3MBTL1 of 5 ± 1 μM was confirmed (Table 4). Compared to the native peptide H4K20Me1, this is a 5-fold increase in binding affinity and an almost 5-fold increase in ligand efficiency.28 Analogous to 7, 14 demonstrated no binding to the D355A mutant of L3MBTL1 (Figure 4A). Together with the ITC-based one-site binding in the wild-type protein, these results suggest that 14 only interacts with L3MBTL1 in the intended binding pocket in the second MBT subdomain of the protein. Finally, to demonstrate histone peptide antagonism with 14, we utilized an FP assay12a, 13, 29 employing the same H3K9Me1 peptide that was utilized in our AlphaScreen assay. Indeed, nicotinamide 14 competes with the FAM-labeled peptide effectively with a of 10 ± 0.4 μM consistent with both the AlphaScreen and ITC results (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

A) ITC binding curve of 14 to wt L3MBTL1 overlayed with the titration using the D355A mutant of L3MBTL1. B) Co-crystal structure of 14 with L3MBTL1. C) Binding curve for 14 in a FP displacement assay with FAM-H3K9Me1.

To further characterize the binding interaction of our most potent ligand with L3MBTL1 and provide a firm structural basis for future directions in probe optimization, a co-crystal structure of L3MBTL1 (residues 200-522 comprising the three MBT repeat) in complex with nicotinamide 14 was obtained at 2.55 Å resolution. Consistent with our mutagenesis studies, structural analysis confirmed the binding of 14 in the methyl-lysine recognition site located in the second MBT module of the protein (Figure 4B). The structure further highlights a binding mode in which the conformationally rigid aliphatic side chain of the ligand inserts into the hydrophobic cage which contains the essential residue D355. The pyrrolidinyl ring adopts an orientation which results in a 2.6 Å separation between the amine and D355, providing a rich mixture of hydrogen bonding, salt bridge and hydrophobic interactions (from ring carbons). Furthermore, the proximity of the amine to key aromatic residues Y386, W382 and F379 in the hydrophobic cage results in additional π-cation interactions. While the ligand lacks other polar interactions with the protein, including a mostly solvent-exposed bromo-nicotinamide anchor, good shape complementarity with the binding pocket gained through the presence of a bulky side chain contributes additional van der Waals interactions towards ligand binding. Of note is the coplanarity of the piperidine moiety and W382. Comparison with the H4K20Me2 structure (Supporting Information) shows that although the orientation of the amine is similar to 14, the less bulky lysine side chain and presence of other non-productive residues results in reduced potency and ligand efficiency for the peptide.

Conclusion

By using a ligand- and structure-based design approach we were able to significantly improve the potency of initial MBT domain hits and determine the first small molecule methyl-lysine binding domain co-crystal structure. While the AlphaScreen technology was useful as a high-throughput assay for discovery and profiling of low affinity hits, ITC was required to develop SAR, confirm and fully characterize small molecule binders of these proteins. Starting with the identification of increased affinities of pyrroldinyl scaffolds, we discovered the conformationally rigid analogue 14 as a low μM binder of L3MBTL1, exhibiting 5-fold greater affinity than the cognate peptide H4K20Me1 and a significantly improved ligand efficiency. Furthermore, 14 is 6-fold selective for L3MBTL1 over its close homolog L3MBTL3 and 10-fold selective over L3MBTL4. Our studies indicate that MBT domains can accommodate larger amines than just mono- and dimethylamines such as pyrrolidines, but that the size of the binding pocket does not allow for methyl substituted pyrrolidine. Further analysis of the co-crystal structure of 14 with L3MBTL1 will provide new directions for further chemistry to improve potency and selectivity. The small molecule binders of MBT domains described are expected to be cell-penetrant and future efforts will also be directed toward functional and cell-based studies to progress toward a high quality chemical probe of these readers of the histone code.30

METHODS

Synthesis

Detailed synthetic procedures and characterizations are described in Supporting Information.

Protein Purification

L3MBTL1 was expressed and purified as described.25a Briefly, cell pellets from a 2 L culture expressing His-tagged L3MBTL1 were lysed with BugBuster protein extraction reagent (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ) containing 20 mM imidazole. The cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation and loaded onto a 5 mL HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated with binding and wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.2, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole) using an ÄKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) at 1 mL/min. His-tagged L3MBTL1 was eluted using a linear gradient of elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.2, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole) over 20 column volumes. Fractions containing L3MBTL1 were confirmed by SDS-PAGE, pooled and loaded at 2 ml/min onto a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 preparative grade size exclusion column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) using an ÄKTA FPLC. A constant flow of 2 ml/min size exclusion buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.02% Tween 20) was used to elute L3MBTL1. Fractions containing L3MBTL1 were identified by SDS-PAGE, pooled and subjected to simultaneous concentration and buffer exchange using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter unit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and storage buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM DTT). Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay and protein purity was determined to by >95% by Coomassie.

The D355A mutant of L3MBTL1 was obtained from the SGC in Toronto and expressed and purified analogously to the wt L3MBTL1.

ITC Experiments

For the ITC measurements, L3MBTL1 was extensively dialyzed into ITC buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 25 mM NaCl and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Subsequently, the concentration was established using the Edelhoch method.31 The ITC experiments were performed at 25 °C, using an AutoITC200 microcalorimeter (GE MicroCal Inc., USA). Experiments were performed by injecting 1.5 μl of 1 mM solution of the compounds into a 200 μL sample cell containing 50 μM L3MBTL1. A total of 26 injections were performed with a spacing of 180 seconds and a reference power of 8 μcal/s. Compounds were dissolved in ITC buffer at 10 mM and diluted to 1 mM. A control experiment for each compound was also performed and the heat of dilution was measured by titrating each compound into buffer alone. The heat of dilution generated by the compounds was subtracted, and the binding isotherms were plotted and analyzed using Origin Software (MicroCal Inc., USA). The ITC measurements were fit to a one-site binding model. The ITC experiments using the D355A mutant of L3MBTL1 were performed analogously to the above mentioned procedure.

Fluorescence polarization displacement assay

A histone peptide consisting of residues 1-15 of the H3 histone tail containing an N-terminal fluorescein, a 6-aminohexanoic acid linker, and monomethyl lysine at position 9 (FAM-H3K9Me1)12a, 13 was used as the fluorescent probe to bind L3MBTL1 in the FP displacement assay (FAM-AHA-ARTKQTARK(Me)STGGKA-CO2H). Binding assays were carried out in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.), 25 mM NaCl, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol in black 384-well microplates (Corning, non-binding surface) with a final volume of 30 μL per well. To each well, 20 μL of a 150 nM stock solution of H3 FAM-K9Me was added to give a final concentration of 100 nM, followed by 5 μL of a 120 μM stock solution of L3MBTL1 to give a final protein concentration of 20 μM. Serial dilutions were prepared of inhibitor UNC669 (14) and added (5 μL) to give a final concentration range of 0-400 μM. Plates were incubated for 20 min at room temperature prior to analysis. FP measurements (mP) were made on an AcQuest (LJL BioSystems) plate reader at room temperature, with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and the emission collected at 530 nm. The G factor was determined to be 0.92 from a standard solution of fluorescein and corrected for by the instrument software. All measurements were made in triplicate with 10 readings collected in each measurement.

Crystallization, data collection and structure determination

Purified protein was obtained using methods established previously for the three-MBT repeat (3MBT) domain of human L3MBTL1 (residues 200-522).12b Crystallization was performed using a protein sample concentrated to 10 mg/mL and pre-incubated with 1 mM compound 14 (UNC669). Initial screening was carried out by sitting drop vapor diffusion at room temperature using an in-house sparse-matrix crystallization screen, yielding needles which appeared after four days in a condition containing 25% PEG 3350, 0.1 M ammonium sulfate, and 0.1 M Bis-Tris buffer pH 5.5. The crystals belong to the trigonal space group P32 with unit cell dimensions of a = b = 106.3 Å, and c = 90.1 Å, containing three molecules in the asymmetric unit. A single crystal was cryoprotected by soaking in well solution with 18% glycerol (v/v) for 60 s before flash freezing in liquid nitrogen.

Diffraction data were collected at 100 °K using synchrotron radiation at the Canadian Macromolecular Crystallography Facility (CMCF) on beamline 08ID-1 at the Canadian Light Source (Saskatoon, SK, Canada). Intensities were integrated and scaled using HKL2000.32 The structure of 3MBT/UNC669 complex was solved by the molecular replacement method as implemented by MOLREP in the CCP4 program suite33 using the structure of human 3MBT domain in complex with 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) (PDB 2RJC) as a search model. Following alternate cycles of restrained refinement and manual model rebuilding using COOT,34 the improved model revealed clear electron density allowing unambiguous placement of the bound ligand 14 (UNC669) in the methyl-lysine binding site of two of three protein chains. The inhibitor was not modeled in the third chain (chain C) owing to poorly defined electron density. All refinement steps were performed using REFMAC35 in the CCP4 program suite. The final model comprising three molecules of 3MBT domain, two molecules of UNC669, and solvent molecules including glycerol and sulfate molecules refined to an Rwork of 19.1% and Rfree of 24.2%. Data collection and structure refinement statistics are summarized in the Supporting Information (SI, Table 1). Structure figures were prepared using PyMOL.36 Atomic coordinates and structure factors for 3MBT/UNC669 complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 3P8H.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by NIH grant number RC1GM090732 and the Ontario Research Fund and the Structural Genomics Consortium, a registered charity (Number 1097737) that receives funds from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute, GlaxoSmithKline, Karolinska Institute, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Ontario Innovation Trust, the Ontario Ministry for Research and Innovation, Merck & Co. Inc., the Novartis Research Foundation, the Swedish Agency for Innovation Systems, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, and the Wellcome Trust. Post-doctoral fellowships for JMH and TJW from the Carolina Partnership are gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Shiamalee Perumal (GE) for helpful discussions concerning ITC, Dr. Keduo Qian and Professor K. H. Lee for HRMS support, Dr. Krzysztof Krajewski and Professor Brian Strahl for support with peptide synthesis, Farrell MacKenzie for supply of D355A L3MBTL1 construct, Dr. Chuanbing Bian for expression and purification of PHF13, Mani Ravichandran for expression and purification of FLAG-CBX7, Dr. Hui Ouyang for expression and purification of L3MBTL1 (MBT repeat containing residues 200-522) for crystallization, and Dr. Wolfram Tempel for assistance with data collection.

a Abbreviations

- Rb

retinoblastoma protein

- MBT

malignant brain tumor

- L3MBTL1

lethal(3) malignant brain tumor protein 1

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- H4

histone 4

- PWWP

proline-tryptophan-tryptophan-proline

- PHD

plant homeodomain

- KMe1

monomethyl-lysine

- H4K20Me1

histone H4 lysine 20 monomethyl

- E2F

E2 transcription factor

- SMYD2

SET and MYND domain-containing protein 2

- SFMBT1

SCM-related gene containing four MBT domains

- MBTD1

MBT domain containing 1

- PHF13

PHD finger protein 13

- CBX7

chromobox 7

- FAM

carboxyfluorescein

- FP

fluorescence polarization

Footnotes

The coordinates and structure factors of the co-crystal structure of the L3MBTL1-14 complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org, PDB code 3P8H).

Supporting Information Available: ITC binding curves, co-crystal structure refinements and experimental procedures including spectra for all final compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev. 2009;23(7):781–783. doi: 10.1101/gad.1787609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. The mammalian epigenome. Cell. 2007;128(4):669–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nirmalanandhan VS, Sittampalam GS. Stem cells in drug discovery, tissue engineering, and regenerative medicine: emerging opportunities and challenges. J. Biomol. Screen. 2009;14(7):755–768. doi: 10.1177/1087057109336591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelato KA, Fischle W. Role of histone modifications in defining chromatin structure and function. Biol. Chem. 2008;389(4):353–363. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5 (a).Liu F, Chen X, Allali-Hassani A, Quinn AM, Wasney GA, Dong A, Barsyte D, Kozieradzki I, Senisterra G, Chau I, Siarheyeva A, Kireev DB, Jadhav A, Herold JM, Frye SV, Arrowsmith CH, Brown PJ, Simeonov A, Vedadi M, Jin J. Discovery of a 2,4-diamino-7-aminoalkoxyquinazoline as a potent and selective inhibitor of histone lysine methyltransferase G9a. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52(24):7950–7953. doi: 10.1021/jm901543m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Copeland RA, Solomon ME, Richon VM. Protein methyltransferases as a target class for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8(9):724–732. doi: 10.1038/nrd2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu F, Chen X, Allali-Hassani A, Quinn AM, Wigle TJ, Wasney GA, Dong A, Senisterra G, Chau I, Siarheyeva A, Norris JL, Kireev DB, Jadhav A, Herold JM, Janzen WP, Arrowsmith CH, Frye SV, Brown PJ, Simeonov A, Vedadi M, Jin J. Protein lysine methyltransferase G9a inhibitors: design, synthesis, and structure activity relationships of 2,4-diamino-7-aminoalkoxy-quinazolines. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53(15):5844–5857. doi: 10.1021/jm100478y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, Morse EM, Keates T, Hickman TT, Felletar I, Philpott M, Munro S, McKeown MR, Wang Y, Christie AL, West N, Cameron MJ, Schwartz B, Heightman TD, La Thangue N, French CA, Wiest O, Kung AL, Knapp S, Bradner JE. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468:1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kireev D, Wigle TJ, Norris-Drouin J, Herold JM, Janzen WP, Frye SV. Identification of non-peptide malignant brain tumor (MBT) repeat antagonists by virtual screening of commercially available compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53(21):7625–7631. doi: 10.1021/jm1007374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8 (a).Campagna-Slater V, Arrowsmith AG, Zhao Y, Schapira M. Pharmacophore Screening of the Protein Data Bank for Specific Binding Site Chemistry. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010;22:358–367. doi: 10.1021/ci900427b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Campagna-Slater V, Schapira M. Finding Inspiration in the Protein Data Bank to Chemically Antagonize Readers of the Histone Code. Mol. Inf. 2010;29:322–331. doi: 10.1002/minf.201000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) Database. 2010.

- 10.Adams-Cioaba MA, Min J. Structure and function of histone methylation binding proteins. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009;87(1):93–105. doi: 10.1139/O08-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonasio R, Lecona E, Reinberg D. MBT domain proteins in development and disease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;21(2):221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12 (a).Li H, Fischle W, Wang W, Duncan EM, Liang L, Murakami-Ishibe S, Allis CD, Patel DJ. Structural basis for lower lysine methylation state-specific readout by MBT repeats of L3MBTL1 and an engineered PHD finger. Mol. Cell. 2007;28(4):677–691. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Min J, Allali-Hassani A, Nady N, Qi C, Ouyang H, Liu Y, MacKenzie F, Vedadi M, Arrowsmith CH. L3MBTL1 recognition of mono- and dimethylated histones. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14(12):1229–1230. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalakonda N, Fischle W, Boccuni P, Gurvich N, Hoya-Arias R, Zhao X, Miyata Y, Macgrogan D, Zhang J, Sims JK, Rice JC, Nimer SD. Histone H4 lysine 20 monomethylation promotes transcriptional repression by L3MBTL1. Oncogene. 2008;27(31):4293–4304. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14 (a).Trojer P, Li G, Sims RJ, 3rd, Vaquero A, Kalakonda N, Boccuni P, Lee D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Nimer SD, Wang YH, Reinberg D. L3MBTL1, a histone-methylation-dependent chromatin lock. Cell. 2007;129(5):915–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boccuni P, MacGrogan D, Scandura JM, Nimer SD. The Human L(3)MBT Polycomb Group Protein Is a Transcriptional Repressor and Interacts Physically and Functionally with TEL (ETV6) J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(17):15412–15420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Koga H, Matsui S, Hirota T, Takebayashi S, Okumura K, Saya H. A human homolog of Drosophila lethal(3)malignant brain tumor (l(3)mbt) protein associates with condensed mitotic chromosomes. Oncogene. 1999;18(26):3799–3809. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West LE, Roy S, Lachmi-Weiner K, Hayashi R, Shi X, Appella E, Kutateladze TG, Gozani O. The MBT repeats of L3MBTL1 link SET8-mediated p53 methylation at lysine 382 to target gene repression. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(48):37725–37732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saddic LA, West LE, Aslanian A, Yates JR, 3rd, Rubin SM, Gozani O, Sage J. Methylation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor by SMYD2. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(48):37733–37740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurvich N, Perna F, Farina A, Voza F, Menendez S, Hurwitz J, Nimer SD. L3MBTL1 polycomb protein, a candidate tumor suppressor in del(20q12) myeloid disorders, is essential for genome stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107(52):22552–22557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017092108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perna F, Gurvich N, Hoya-Arias R, Abdel-Wahab O, Levine RL, Asai T, Voza F, Menendez S, Wang L, Liu F, Zhao X, Nimer SD. Depletion of L3MBTL1 promotes the erythroid differentiation of human hematopoietic progenitor cells: possible role in 20q- polycythemia vera. Blood. 2010;116:2812–2821. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Northcott PA, Nakahara Y, Wu X, Feuk L, Ellison DW, Croul S, Mack S, Kongkham PN, Peacock J, Dubuc A, Ra Y-S, Zilberberg K, McLeod J, Scherer SW, Rao J. Sunil, Eberhart CG, Grajkowska W, Gillespie Y, Lach B, Grundy R, Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, Van Meter T, Carlotti CG, Boop F, Bigner D, Gilbertson RJ, Rutka JT, Taylor MD. Multiple recurrent genetic events converge on control of histone lysine methylation in medulloblastoma. Nat. Genet. 2009;41(4):465–472. doi: 10.1038/ng.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Addou-Klouche L, Adelaide J, Finetti P, Cervera N, Ferrari A, Bekhouche I, Sircoulomb F, Sotiriou C, Viens P, Moulessehoul S, Bertucci F, Birnbaum D, Chaffanet M. Loss, mutation and deregulation of L3MBTL4 in breast cancers. Mol. Cancer. 2010;9(1):213–226. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21 (a).Grimm C, Matos R, Ly-Hartig N, Steuerwald U, Lindner D, Rybin V, Muller J, Muller CW. Molecular recognition of histone lysine methylation by the Polycomb group repressor dSfmbt. EMBO J. 2009;28(13):1965–77. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu S, Trievel RC, Rice JC. Human SFMBT is a transcriptional repressor protein that selectively binds the N-terminal tail of histone H3. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(17):3289–3296. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eryilmaz J, Pan P, Amaya MF, Allali-Hassani A, Dong A, Adams-Cioaba MA, Mackenzie F, Vedadi M, Min J. Structural studies of a four-MBT repeat protein MBTD1. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiedler M, Sanchez-Barrena MJ, Nekrasov M, Mieszczanek J, Rybin V, Muller J, Evans P, Bienz M. Decoding of methylated histone H3 tail by the Pygo-BCL9 Wnt signaling complex. Mol. Cell. 2008;30(4):507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yap KL, Li S, Munoz-Cabello AM, Raguz S, Zeng L, Mujtaba S, Gil J, Walsh MJ, Zhou MM. Molecular interplay of the noncoding RNA ANRIL and methylated histone H3 lysine 27 by polycomb CBX7 in transcriptional silencing of INK4a. Mol. Cell. 2010;38(5):662–674. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25 (a).Wigle TJ, Herold JM, Senisterra GA, Vedadi M, Kireev DB, Arrowsmith CH, Frye SV, Janzen WP. Screening for Inhibitors of Low-Affinity Epigenetic Peptide-Protein Interactions: An AlphaScreenTM-Based Assay for Antagonists of Methyl-Lysine Binding Proteins. J. Biomol. Screen. 2010;15(1):62–71. doi: 10.1177/1087057109352902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Quinn AM, Bedford MT, Espejo A, Spannhoff A, Austin CP, Oppermann U, Simeonov A. A homogeneous method for investigation of methylation-dependent protein-protein interactions in epigenetics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(2):e11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts JF, Lin LN. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal. Biochem. 1989;179(1):131–137. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladbury JE, Chowdhry BZ. Sensing the heat: the application of isothermal titration calorimetry to thermodynamic studies of biomolecular interactions. Chem. Biol. 1996;3(10):791–801. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds CH, Tounge BA, Bembenek SD. Ligand Binding Efficiency: Trends, Physical Basis, and Implications. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51(8):2432–2438. doi: 10.1021/jm701255b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vedadi M, Arrowsmith CH, Allali-Hassani A, Senisterra G, Wasney GA. Biophysical characterization of recombinant proteins: a key to higher structural genomics success. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;172(1):107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frye SV. The art of the chemical probe. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6(3):159–161. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4(11):2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-Ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific LLC; San Carlos, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.