Abstract

Background

Little is known about the associations between depressive symptoms, social support and antihypertensive medication adherence in older adults.

Purpose

We evaluated the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between depressive symptoms, social support and antihypertensive medication adherence in a large cohort of older adults.

Methods

A cohort of 2,180 older adults with hypertension was administered questionnaires, which included the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale, the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Index, and the hypertension-specific Morisky Medication Adherence Scale at baseline and 1 year later.

Results

Overall, 14.1% of participants had low medication adherence, 13.0% had depressive symptoms, and 33.9% had low social support. After multivariable adjustment, the odds ratios that participants with depressive symptoms and low social support would have low medication adherence were 1.96 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43, 2.70) and 1.27 (95% CI 0.98, 1.65), respectively, at baseline and 1.87 (95% CI 1.32, 2.66) and 1.30 (95% CI 0.98, 1.72), respectively, at 1 year follow-up.

Conclusion

Depressive symptoms may be an important modifiable barrier to antihypertensive medication adherence in older adults

Keywords: Hypertension, Medication adherence, Depressive symptoms, Social support, Medication possession ratio, Older adults

Introduction

Despite progress in prevention, detection, and treatment, hypertension persists as a major public health challenge with only 37% of US adults with hypertension having controlled blood pressure [1–3]. Low adherence to prescribed medication is one of the major contributors to poor blood pressure control [4] and is associated with higher costs of medical care [5, 6]. A meta-analysis revealed that depressed patients were three times more likely than non-depressed patients to be non-adherent to medical treatment recommendations including medications, diet, and behavior changes [7]. This meta-analysis was limited to 20 studies of children and adults with symptomatic diseases (e.g., cancer, angina) and assessed a variety of medication treatment approaches. Although some studies have reported an association between depressive symptoms and antihypertensive medication adherence [8–11], less is known about how depression might affect adherence to prescription medications for hypertension in older adults, a population with high rates of chronic disease, depression, low social support and low medication adherence.

Inconsistent results have been reported regarding the relationship between low social support and low antihypertensive medication adherence, although there are more studies reporting a positive relationship [9, 12–14]. Low social support may be prevalent among older adults as a result of death and illness of friends and family members or social withdrawal and isolation resulting from depression; thus, low social support may be a common risk factor for low medication adherence in older adults.

The purpose of this analysis was to determine associations between depressive symptoms, social support, and antihypertensive medication adherence in older adults. To do so, we analyzed baseline and 1-year follow-up data from 2,180 community-dwelling participants 65 years of age and older enrolled in the Cohort Study of Medication Adherence among Older Adults (CoSMO) [15].

Methods

Study Population and Timeline

The study design, recruitment flowchart, and baseline characteristics have been previously described [15]. In brief, adults, 65 years and older with treatment for essential hypertension, were randomly selected from the roster of a large managed care organization in southeastern Louisiana. Recruitment was conducted from August 21, 2006 to September 30, 2007, and 2,194 participants were enrolled. Those who refused to participate (n=2,217) compared with participants were more likely to be male (50.4% versus 41.5%, p<0.001), white (84.5% versus 68.8%, p<0.001), and older (76.3 years versus 74.5 years, p<0.001). For the current analysis, 14 participants who reported their race to be other than white or black were excluded leaving 2,180 adults for analysis. The mean age of study participants (n= 2,180) at baseline was 75.0±5.6 years, 30.7% were black, 58.5% were women, 62.8% had hypertension duration >10 years, and 83.6% filled two or more classes of antihypertensive medications in the last year [15]. The 1-year follow-up survey was conducted from September 4, 2007 to December 6, 2008 with a 93% recapture rate (n= 2,003). Forty-two (1.9%) participants died prior to the follow-up survey. The non-responders to the follow-up survey (n=149) compared to responders were more likely to be black (40.3% versus 29.9%, p=0.04) and less likely to have graduated high school (71.0% versus 80.0%; p=0.01). All participants provided verbal informed consent [15, 16], and CoSMO was approved by the Ochsner Clinic Foundation’s Institutional Review Board and the privacy board of the managed care organization.

Study Measures

Both the baseline and 1-year follow-up surveys were administered by telephone using trained interviewers. Of relevance to the current analyses, the surveys included assessment of socio-demographic factors, medication adherence, depressive symptoms, and social support. In addition, information regarding comorbid conditions and pharmacy fills for antidepressant and antihypertensive medications was obtained from the administrative databases of the managed care organization.

Socio-demographic and Clinical Factors

Age, gender, race, marital status, education, and duration of hypertension were obtained through self-report. Comorbid conditions were extracted from the administrative database of the managed care organization and used to generate the Charlson comorbidity index [17, 18]. The most common comorbid conditions identified were diabetes (43.2%), cerebrovascular disease (24.3%), chronic pulmonary disease (18.9%), peripheral vascular disease (16.7%), and congestive heart failure (16.7%). The number of antihypertensive medication classes filled in the year prior to the baseline survey was obtained from the pharmacy databases of the managed care organization.

Medication Adherence

Self-reported antihypertensive medication adherence was ascertained using the eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8). This measure was designed to facilitate the identification of barriers to and behaviors associated with adherence to chronic medications and has been determined to be reliable (α=0.83) and significantly associated with blood pressure control (p<0.05) in individuals with hypertension (i.e., low adherence levels were associated with lower rates of blood pressure control) [12]. Also, it has been shown to have high concordance with antihypertensive medication pharmacy fill rates [19]. Scores on the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale can range from zero to eight; with scores of <6, 6 to <8, and 8 reflecting low, medium and high adherence, respectively [12]. Provided at least 75% of the scale was completed, missing items were generated using the CoSMO sample median score for the item prior to calculating the adherence score; 99.2% of participants completed all 8 items of the scale in the baseline survey with the remaining 0.8% completing at least 75% of the items. At follow-up, 98.2% completed all eight items with all but three of the remaining participants completing at least 75% of the items. In order to focus the current analyses on identifying individuals with low medication adherence, we grouped the scale scores into two categories: low (scores<6) and medium or high adherence (scores≥6).

For the sensitivity analyses using an objective measure of antihypertensive medication adherence, pharmacy fill data were extracted from administrative databases for the year prior to completion of the baseline survey. These data include a listing of all antihypertensive prescriptions, date filled, drug class, and number of pills dispensed. Using pharmacy fill data, the medication possession ratio, the sum of the days’ supply obtained between the first pharmacy fill and the last fill with the supply obtained in the last fill excluded divided by the total number of days in this time period was calculated [15, 19]. The medication possession ratio for each antihypertensive medication class was averaged across all classes to assign a single medication possession ratio to each participant. Using a published cut-point, non-persistent medication adherence using pharmacy fill data was defined as a medication possession ratio <0.8 [19–23]. There were 2,087 participants who had at least three pharmacy fills and were included in the analyses of pharmacy fill data at baseline.

Depressive symptoms were determined with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. The scale has been shown to be a reliable measure for assessing the number, types, and duration of depressive symptoms [24–26]. A depressive symptom score was calculated using published guidelines [25], provided that at least 75% of the scale’s items were completed. Overall, 95% of participants completed all 20 items and 99.9% of participants completed at least 75% of items at baseline; at follow-up, 93.7% completed all 20 items, 99.1% completed 75% with less than 1% excluded. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale scores can range from 0 to 60 with a score ≥16 defining the presence of depressive symptoms [24]. Using this cut point, participants were categorized as having depressive symptoms (yes versus no) to increase the clinical relevance of the findings.

Social support was ascertained using the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey. Using a previously published algorithm [27, 28], a calibrated score for social support was generated provided at least 50% of the items were completed; 92.7% of participants completed all 19 items and 100% completed at least 50% of the items. The scale scores were transformed to a 0–100 scale with a higher score indicating a higher level of social support; validity and reliability of the scale have been demonstrated [27, 28]. Because there are no established cut points for Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale, we used the scale score distribution from the current study population to categorize participants into tertiles: low (score <75), medium (score 75 to <96) and high (score 96 to 100) social support. We combined participants in the medium and high tertiles of social support and compared this group to their counterparts in the low tertile to enhance clinical relevance of the findings.

Antidepressant medication use was determined using the pharmacy database of the managed care organization. The antidepressant medication classes included tricylics, dibenzoxapine tricyclics, tetracyclics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and monamine oxidate inhibitors. Participants having filled at least one prescription for antidepressant medication within 60 days of the baseline survey date were recorded as using antidepressant medication.

Statistical Analysis

Primary Analyses

We assessed the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between depressive symptoms, social support, and medication adherence using the self-reported scale. Socio-demographic characteristics were calculated for participants with and without depressive symptoms and with and without low social support at baseline. The significance of differences across groupings was determined using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. The interaction of social support and depressive symptoms on low antihypertensive medication adherence was not significant (p=0.34). Hence, main effects for social support and depressive symptoms were examined. Separate, binary logistic regression models with forced entry were used to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) of low antihypertensive medication adherence associated with depressive symptoms and low social support at baseline. Initially, models included adjustment for age, gender, race, education, marital status and comorbidity. Subsequent models adjusted for the other factor (i.e., depressive symptoms were adjusted for low social support and vice-versa). Because we identified a significant association between depressive symptoms and low medication adherence after multivariable adjustment, we evaluated the consistency of the association among demographic subgroups. The statistical significance across subgroups (i.e., interactions) was also assessed. This analysis was repeated with 1-year follow-up data and the results were similar; data from the baseline year are provided in the results. Finally, the association of depressive symptoms with low antihypertensive medication adherence was determined separately for participants using and not using antidepressant medication.

Next, we examined the longitudinal relationship between depressive symptoms, low social support, and antihypertensive medication adherence in two ways. First, we assessed the relationships between depressive symptoms and low social support at baseline with the prevalence of low medication adherence after 1 year of follow-up. Second, we evaluated the relationship between new onset depressive symptoms and new onset low social support with new onset low medication adherence in the follow-up year to assess the consistency of the findings. For the latter analyses, we restricted the sample to participants with medium or high antihypertensive medication adherence and no depressive symptoms at baseline (n=1,479) in one analysis and medium or high antihypertensive medication adherence and medium to high social support at baseline (n=1,077) in a separate analysis. For the longitudinal and incidence analyses, we used binary logistic regression models adjusted for age, gender, race, education, marital status and comorbidity. Subsequent models adjusted for the other factor (i.e., depressive symptoms was adjusted for low social support and vice-versa)

Sensitivity Analyses

The cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses were repeated using the antihypertensive pharmacy fill rates (i.e., medication possession ratio) as the measure of medication adherence to determine if the results using an objective measure of adherence were consistent with the primary results. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (Cary, NC).

Results

Participant Characteristics

At baseline, 14.1% of participants reported low adherence to antihypertensive medications, 13.0% reported depressive symptoms, and 33.9% reported low social support. A higher percentage of those with, versus without, depressive symptoms were women, black, not married, had less than a high school education, two or more comorbid conditions and were taking a higher number of antihypertensive medication classes (Table 1). Women, blacks, unmarried participants, those with less than a high school education, and with less than two comorbid conditions were more likely to have low social support. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was significantly higher in participants with low versus medium or high social support (22.1% versus 8.4%, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by the presence of depressive symptoms and low social support

| Depressive symptoms

|

Low social support

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=1,895) | Yes (n=284) | p value | No (n=1,442) | Yes (n=738) | p value | |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 75.1 (5.6) | 74.9 (5.4) | 0.602 | 75.1 (5.6) | 74.9 (5.4) | 0.396 |

| Women,% | 57.3 | 66.2 | 0.005 | 56.3 | 62.7 | 0.004 |

| Black,% | 29.9 | 36.3 | 0.030 | 28.4 | 35.4 | <0.001 |

| Not currently married,% | 42.0 | 51.8 | 0.002 | 37.3 | 54.9 | <0.001 |

| Less than a high school graduate,% | 18.9 | 32.5 | <0.001 | 19.2 | 23.6 | 0.017 |

| Comorbid index score≥2,% | 48.0 | 60.1 | <0.001 | 51.1 | 46.6 | 0.047 |

| Hypertension duration≥10 years,% | 62.6 | 65.8 | 0.296 | 63.6 | 62.0 | 0.458 |

| Number of antihypertensive medication classes, mean number (SD) | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.2) | <0.001 | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.2) | 0.121 |

Depressive symptoms were defined as a score ≥16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale

Low social support was defined as a score <75 on the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support index

SD Standard deviation

Primary Analyses

Low Antihypertensive Medication Adherence using Self-Report

Baseline Analyses

At baseline, the prevalence of low antihypertensive medication adherence was 23.6% and 12.7% for those with and without depressive symptoms, respectively (Table 2). Depressive symptoms remained associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence after adjustment for socio-demographics and comorbidity, and after further adjustment for social support. The prevalence of low antihypertensive medication adherence was 17.2% for those with low social support and 12.5% for those with medium to high social support. Low social support remained associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence after adjustment for socio-demographics and comorbidity; however, after further adjustment for depressive symptoms, the association was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Prevalence and odds ratios of low antihypertensive medication adherence by depressive symptoms and level of social support

| No depressive symptoms (n=1,895) | Depressive symptoms (n=284) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) adherence score | 7.28 (1.03) | 6.85 (1.32) | <0.01 |

| Low adherencea | |||

| Prevalence,% | 12.7 | 23.6 | <0.01 |

| Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 2.09 (1.53, 2.86) | <0.01 |

| Adjustedc OR (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.96 (1.43, 2.70) | <0.01 |

| Medium to high social support (n=1,442) | Low social support (n=738) | p value | |

| Mean (SD) adherence score | 7.28 (1.03) | 7.11 (1.17) | <0.01 |

| Low adherencea | |||

| Prevalence,% | 12.5 | 17.2 | 0.01 |

| Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.41 (1.10, 1.82) | <0.01 |

| Adjustedd OR (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.27 (0.98, 1.65) | 0.07 |

Mean adherence score was assessed with the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 item

Depressive symptoms were defined as a score ≥16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale

Low social support was defined as a score <75 on the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support index

OR Odds ratio, CI Confidence interval, SD Standard deviation

Low antihypertensive medication adherence was defined as a Morisky Medication Adherence Scale score <6

Adjusted for age, gender, race, education, marital status and Charlson comorbidity score

Adjusted for age, gender, race, education marital status, Charlson comorbidity score and social support

Adjusted for age, gender, race, education marital status, Charlson comorbidity score and depression

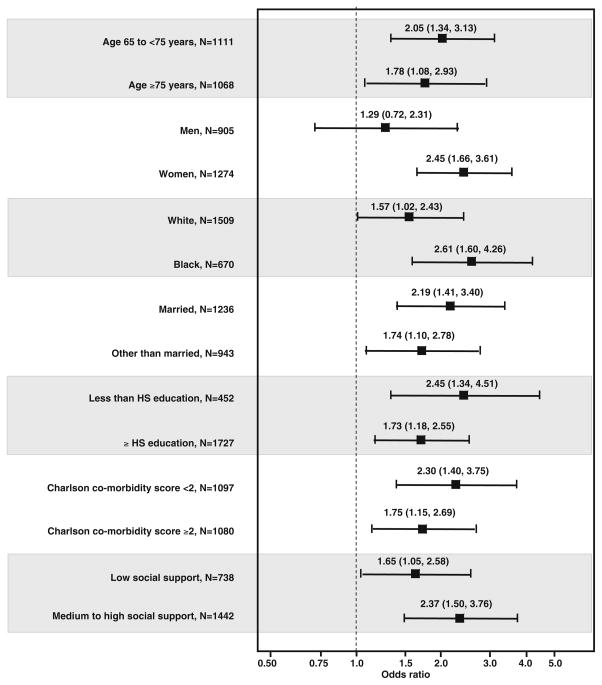

Within each sub-group except men, depressive symptoms were associated with a significantly higher odds ratio of low antihypertensive medication adherence (Fig. 1). There were no significant interactions between the presence of depressive symptoms and demographics (including gender), comorbidity, and social support strata on low antihypertensive medication adherence (p>0.05 for each comparison).

Fig. 1.

Adjusted odds ratios of low antihypertensive medication adherence associated with the presence of depressive symptoms by demographics, Charlson comorbidity scores, and level of social support. Odds ratios were calculated using models that included age, gender, race, education, marital status, Charlson comorbidity score and social support; HS high school; p values for interactions across subgroups were not significant. Square represents odds ratio, line represents 95% confidence interval

In the CoSMO population, 10.6% (n=231/2,180) of participants were using antidepressant medications at baseline; 28.5% (66/231) of those using antidepressant medications had depressive symptoms compared to 11.2% (218/1,949) of those not using antidepressant medications. After multivariable adjustment, low antihypertensive medication adherence was associated with depressive symptoms among individuals taking and not taking antidepressant medications (Table 3). No interaction was present between antidepressant medication use and depressive symptoms with low antihypertensive medication adherence (p interaction=0.84).

Table 3.

Prevalence and odds ratios of low antihypertensive medication adherence associated with depressive symptoms among participants taking and not taking antidepressant medication

| No use of antidepressant medication

|

Use of antidepressant medicationa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No depressive symptoms (n=1,730) | Depressive symptoms present (n=218) | p value | No depressive symptoms (n=165) | Depressive symptoms present (n=66) | p value | |

| Mean (SD) adherence score | 7.28 (1.03) | 6.87 (1.33) | <0.01 | 7.24 (0.97) | 6.80 (1.30) | 0.02 |

| Low adherenceb | ||||||

| Prevalence,% | 12.4 | 22.0 | <0.01 | 15.8 | 28.8 | 0.03 |

| Adjustedc OR(95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.97 (1.37, 2.83) | <0.01 | 1 (reference) | 2.15 (1.06, 4.35) | 0.03 |

Mean adherence score was assessed with the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 item

Depressive symptoms were defined as a score ≥16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale

Using antidepressant medication—Participant filled at least one antidepressant medication within 60 days prior to the survey

Low antihypertensive medication adherence—Morisky Medication Adherence Scale score <6

Adjusted for age, gender, race, education, marital status and Charlson comorbidity score

OR Odds ratio, CI Confidence interval, SD Standard Deviation

Longitudinal Analysis

Using the entire sample, the odds ratios that participants with depressive symptoms and low social support at baseline would have low antihypertensive medication adherence at 1-year follow-up were 1.87 (95% CI 1.32, 2.66) times and 1.30 (95% CI 0.98, 1.72), respectively (Table 4). Among participants with medium or high antihypertensive medication adherence and no depressive symptoms at baseline, 7.2% had low antihypertensive medication adherence at the 1-year follow-up survey. Among participants with medium or high antihypertensive medication adherence and in the medium or high tertile of social support at baseline, 7.3% had low antihypertensive medication adherence at 1-year follow-up. After multivariable adjustment, the odds ratio that participants with new onset depressive symptoms at the 1-year follow-up would have incident low antihypertensive medication adherence at the 1-year follow-up was 2.07 (95% CI 1.11, 3.84). In contrast, new onset low social support was not associated with incident low antihypertensive medication adherence (OR=0.91; 95% CI 0.50, 1.66).

Table 4.

Prevalence and odds ratios of low antihypertensive medication adherence at one year follow-up by depressive symptoms and level of social support at baseline

| No depressive symptoms (n=1,710) | Depressive symptoms (n=242) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) adherence score | 7.30(1.01) | 6.84(1.32) | <0.01 |

| Low adherencea | |||

| Prevalence,% | 12.2 | 22.3 | <0.01 |

| Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 2.00 (1.42, 2.82) | <0.01 |

| Adjustedc OR (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.87(1.32, 2.66) | <0.01 |

| Medium to high social support (n=1,308) | Low social support (n=645) | p value | |

| Mean (SD) adherence score | 7.32 (0.99) | 7.11 (1.20) | <0.01 |

| Low adherencea | |||

| Prevalence,% | 11.9 | 16.4 | <0.01 |

| Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.43 (1.09, 1.87) | 0.01 |

| Adjustedc OR (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.30 (0.98, 1.72) | 0.07 |

Mean adherence score was assessed with the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 item

Depressive symptoms were defined as a score ≥16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale

Low social support was defined as a score <75 on the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support index

Participants not prescribed antihypertensive medication in follow-up (n=35) and who did not answer at least 75% of the MMAS (n=3) questions in the follow-up survey were excluded from the analysis.

OR Odds ratio, CI Confidence interval, SD Standard deviation

Low antihypertensive medication adherence was defined as a Morisky Medication Adherence Scale score <6

Adjusted for age, gender, race, education, marital status and Charlson comorbidity score

Adjusted for age, gender, race, education marital status, Charlson comorbidity score and social support

Adjusted for age, gender, race, education marital status, Charlson comorbidity score and depression

Sensitivity Analysis

Low Antihypertensive Medication Adherence using Pharmacy Fill

Baseline Analyses

The prevalence of non-persistent medication possession ratio was 26.7% at baseline. Nonpersistent medication possession ratio was present for 36.5% and 25.3% of participants with and without depressive symptoms, respectively (p<0.01). After multivariable adjustment, the OR for non-persistent medication possession ratio associated with depressive symptoms was 1.53 (95% CI 1.15, 2.03). Additionally, the multivariable adjusted OR for non-persistent medication possession ratio associated with depressive symptoms was 1.60 (95% CI 1.17, 2.19) and 1.62 (95% 0.83, 3.16) for individuals not taking and taking antidepressant medications, respectively. The prevalence of nonpersistent medication possession ratio was 29.9% for those with low social support and 25.1% for those with medium to high social support. After multivariable adjustment, low social support was not associated with non-persistent medication possession ratio (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.91, 1.39, p=0.27).

Longitudinal Analyses

Overall, 23.6% of participants had a non-persistent medication possession ratio at 1-year follow-up. The odds ratio that participants with depressive symptoms at baseline would have non-persistent medication possession ratio at 1-year follow-up was 1.62 (95% CI 1.19, 2.19). The odds ratio that participants with low social support at baseline would have non-persistent medication possession ratio at 1-year follow-up was 1.03 (95% CI 0.82, 1.30).

Discussion

Previous reports indicate many patients with chronic diseases do not adhere to prescribed medications [6] and that a variety of factors may influence medication adherence [15, 29]. Despite the research conducted to date, few data are available on the associations between depressive symptoms, low social support, and low antihypertensive medication adherence in older patients. The current study explored these associations in a large cohort at baseline and 1 year later. We identified a strong association between the presence of depressive symptoms and low antihypertensive medication adherence in cross-sectional, longitudinal, and sensitivity analyses in community-dwelling adults 65 years of age and older. These associations were consistent when using self-report and pharmacy fill measures of adherence. In subgroup analyses, the association between depressive symptoms and low medication adherence was present in women but not in men; however, the interaction was not statistically significant. In >contrast, the association between low social support and low antihypertensive medication adherence was small after adjustment for the presence of depressive symptoms and not confirmed in the longitudinal analysis nor in the sensitivity analysis using the pharmacy fill as the measure of adherence. The consistency of our findings across the spectrum of cross-sectional, longitudinal, and sensitivity analyses provides support that the results are real and likely not due to chance.

Depression is common in patients with hypertension and is associated with adverse health outcomes, poor quality of life and overuse of healthcare resources. [30–33]. Prior reports have demonstrated that depressive symptoms are associated with poor blood pressure control and with the development of complications of hypertension [34]. Investigators have reported cross-sectional associations of depressive symptoms with low antihypertensive medication adherence [9, 35, 36]. More recently, a longitudinal association of depressive symptoms with self-reported low antihypertensive medication adherence, which was mediated by self-efficacy, was identified in a sample of 167 predominantly younger black women with hypertension, Medicaid insurance and enrolled in a clinical trial [37]. In addition to having a substantially larger sample size, the current study extends these prior findings in several important ways. Clinical trials often are limited to select populations and the present cohort study included a diverse population of older adults with hypertension. Also, data were available on two measures of medication adherence (self-report and pharmacy fill), and results were consistent. Furthermore, the association between depressive symptoms and low medication adherence were supported in cross-sectional, longitudinal and sensitivity analyses.

Given the strong association of depressive symptoms with low antihypertensive medication adherence, clinicians should consider screening for depression in patients, in particular women, identified as having low antihypertensive medication adherence or at risk for low adherence. Attention to and treatment of depression in patients with hypertension may be helpful in improving adherence rates and health care outcomes. In a pilot randomized controlled trial of middle aged and older adults (ages 50–80 years), integrating depression and hypertension treatment in primary care practice resulted in a significant reduction of depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale mean scores: 9.9 intervention group versus 19.3 usual care group; p<0.01), improved blood pressure control (mean systolic blood pressure 127.3 mmHg intervention group versus 141.3 control group; p<0.01), and increased rates of medication adherence of both antihypertensive (78.1% intervention group versus 31.3% usual care p<0.01) as well as antidepressant (71.9% intervention group versus 31.3% usual care; p<0.01) medication [38]. Although benefits of co-management of hypertension and depression were evident in this previous trial, health care providers are well aware of the challenges of delayed onset of efficacy of antidepressants and the high proportion of depressed patients being poor or non-responders to antidepressant medication [39]. To this point, 28.5% of CoSMO participants using antidepressant medication had depressive symptoms. Our study highlights the importance of assessment and ongoing management of depressive symptoms after initiating antidepressant therapy: participants with depressive symptoms, despite using anti-depressant medications, had the highest odds of low antihypertensive medication adherence. Consideration should be given to using psychosocial interventions in combination with medical therapy to improve adherence for patients with chronic diseases [40–42]. The practicing physician and other health care providers should be cognizant of the effects of antidepressant medications on blood pressure [43, 44] and extra care should be taken when treating depression in hypertensive older patients to minimize the side effects on blood pressure of antidepressant medication [34].

In several prior studies, social support has been associated with higher levels of antihypertensive medication adherence [10, 13, 14] and in others it has not [9]. In the current study, the association between social support and self-reported antihypertensive medication adherence was attenuated and not significant after adjustment for depressive symptoms in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. It may be that depressive symptoms mediate the relationship between low social support and low medication adherence. Low social support may lead to an increase in depressive symptoms which negatively impact medication adherence. While social support may be an important factor in maintaining antihypertensive medication adherence, this association was much weaker than that for depressive symptoms in the current study and warrants further study.

Study Limitations and Strengths

Our study focused on the presence of depressive symptoms using a validated tool; yet, a formal diagnosis of depression and duration of depression were not ascertained. Nevertheless, the association between depressive symptoms and low antihypertensive medication adherence even in participants using antidepressant medication reveals that depressive symptoms have a negative effect on antihypertensive medication adherence. The primary medication adherence measure in the current study was self-report, which may have led to the over-estimation of adherence due to social desirability and recall biases. However, our prior work has revealed high concordance between the MMAS-8 and antihypertensive pharmacy fill data [19] and the present findings were consistent when the analyses were repeated using pharmacy fill as the measure of medication adherence. It is noteworthy that there is no gold standard for measuring medication adherence and each method (e.g., self-report, pharmacy fill) has limitations [6, 8, 45]. Finally, the current study was limited to English-speaking adults 65 years of age and older with health insurance in one region of the US.

Despite these limitations, the inclusion of a large sample of community-dwelling older adults, longitudinal design, broad data collection, access to administrative data, and high follow-up capture rate are strengths of this study. The study population is diverse with respect to socio-demographics and the presence of risk factors. Pharmacy fill data were available to objectively assess use of antihypertensive medication adherence for sensitivity analyses. The restriction of our sample to older adults in a managed care setting minimizes the confounding effects of health insurance, access to medical care, and employment status in older adults.

Conclusions

The presence of depressive symptoms is associated with low antihypertensive medication adherence in older adults. It is important for physicians and other healthcare providers to consider depressive symptoms as a modifiable factor when low antihypertensive medication adherence is identified.

Acknowledgments

Source of Support The project described was supported by Grant Number R01 AG022536 from the National Institute on Aging (Dr. Krousel-Wood, principal investigator). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the CoSMO Advisory Panel members including Jiang He MD, PhD (Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, LA), Richard Re MD (Ochsner Clinic Foundation, New Orleans, LA), and Paul K Whelton MD (Loyola University Medical Center, Chicago, IL).

Footnotes

Dr. Krousel-Wood, principal investigator, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure None.

Contributor Information

Marie Krousel-Wood, Email: mawood@ochsner.org, Center for Health Research, Ochsner Clinic Foundation, 1514 Jefferson Highway, New Orleans, LA 70121, USA. Department of Epidemiology, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Tareq Islam, Department of Epidemiology, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

Paul Muntner, Department of Epidemiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

Elizabeth Holt, Center for Health Research, Ochsner Clinic Foundation, 1514 Jefferson Highway, New Orleans, LA 70121, USA

Cara Joyce, Department of Biostatistics, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

Donald E. Morisky, Department of Community Health Sciences, UCLA School of Public Health, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Larry S. Webber, Department of Biostatistics, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

Edward D. Frohlich, Department of Cardiology-Hypertension Section, Ochsner Clinic Foundation, New Orleans, LA, USA

References

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong KL, Cheung BM, Man YB, Lau CP, Lam KS. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2007;49:69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252676.46043.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnier M, Santschi V, Favrat B, et al. Monitoring compliance in resistant hypertension: Important step in patient management. J Hypertens. 2003;21:S37–S42. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200305002-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43:521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: A quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: A meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002;40:794–811. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris AB, Li J, Kroenke K, Bruner-England TE, Young JM, Murray MD. Factors associated with drug adherence and blood pressure control in patients with hypertension. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:483–492. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang PS, Bohn RL, Knight E, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J. Noncompliance with antihypertensive medications: The impact of depressive symptoms and psychosocial factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:504–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.00406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maguire LK, Hughes CM, McElnay JC. Exploring the impact of depressive symptoms and medication beliefs on medication adherence in hypertension—a primary care study. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang PS, Avorn J, Brookhart MA, et al. Effects of non-cardiovascular comorbidities on antihypertensive use in elderly hypertensives. Hypertension. 2005;46:273–279. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000172753.96583.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood MA, Ward H. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23:207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Strauman TJ, Robins C, Sherwood A. Social support and coronary heart disease: Epidemiologic evidence and implications for treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:869–878. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188393.73571.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Islam T, Morisky DE, Webber LS. Barriers to and determinants of medication adherence in hypertension management: Perspective of the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults (CoSMO) Med Clin N Am. 2009;93:753–769. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Jannu A, Hyre A, Breault J. Does waiver of written informed consent from the Institutional Review Board affect response rate in a low risk research study? J Invest Med. 2006;54:174–179. doi: 10.2310/6650.2006.05031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidiity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM Administrative Databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krousel-Wood MA, Islam T, Webber LS, Morisky DE, Muntner P. New medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in hypertensive seniors. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopjar B, Sales AEB, Pineros SL, Sun H, Yu-Fang L, Hedeen AN. Adherence with statin therapy in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in Veterans Administration male population. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1106–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizzo JA, Simons WR. Variations in compliance among hypertensive patients by drug class: Implications for health care costs. Clin Ther. 1997;19:1446–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sikka R, Xia F, Aubert RE. Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:449–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson E, Beck C, Richard H, Eisenberg MJ, Pilote L. Drug prescriptions after acute myocardial infarction: Dosage, compliance, and persistence. Am Heart J. 2003;145:438–444. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight RG, Williams S, McGee R, Olaman S. Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behav Res Therapy. 1997;35:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts RE, Vernon SW, Rhoades HM. Effects of language and ethnic status on reliability and validity of the CES-D with psychiatric patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177:581–592. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198910000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE. Short-Form General Health Survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26:724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krousel-Wood M, Thomas S, Muntner P, et al. Medication adherence: A key factor in achieving blood pressure control and good clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:357–362. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000126978.03828.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogner HR, Cary MS, Bruce ML, et al. The role of medical comorbidity in outcome of major depression in primary care: The PROSPECT study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:861–868. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Bruce ML. Diabetes, depression, and death: A randomized controlled trial of a depression treatment program for older adults based in primary care (PROSPECT) Diabetes Care. 2007;30:3005–3010. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: Impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278–3285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, Romanelli J, Richter DP, Bush DE. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1818–1823. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scalco AZ, Scalco MZ, Azul JB, Lotufo NF. Hypertension and depression. Clinics. 2005;60:241–250. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322005000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim MT, Han HR, Hill MN, Rose L, Roary M. Depression, substance use, adherence behaviors, and blood pressure in urban hypertensive black men. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:24–31. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoenthaler A, Ogedegbe G, Allegrante JP. Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and medication adherence among hypertensive African Americans. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36:127–137. doi: 10.1177/1090198107309459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogner HR, de Vries HF. Integration of depression and hypertension treatment: A pilot, randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:295–301. doi: 10.1370/afm.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henkel V, Seemuller F, Obermeier M, et al. Does early improvement triggered by antidepressants predict response/remission?—Analysis of data from a naturalistic study on a large sample of inpatients with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2008;115:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delamater AM. Improving patient adherence. Clinical Diabetes. 2006;24:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kahana S, Drotar D, Frazier T. Meta-analysis of psychological interventions to promote adherence to treatment in pediatric chronic health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:590–611. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lebowitz BD. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1996;4:S3–S6. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amsterdam JD, Garcia-Espana F, Fawcett J, et al. Blood pressure changes during short-term fluoxetine treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:9–14. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199902000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scalco MZ, de Almeida OP, Hachul DT, Castel S, Serro-Azul J, Wajngarten M. Comparison of risk of orthostatic hypotension in elderly depressed hypertensive women treated with nortriptyline and thiazides versus elderly depressed normotensive women treated with nortriptyline. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:1156–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00717-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawkshead J, Krousel-Wood MA. Techniques of measuring medication adherence in hypertensive patients in outpatient settings: Advantages and limitations. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2007;15:109–118. [Google Scholar]