Abstract

Evidence for somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes has been observed in all of the species in which immunoglobulins have been found. Previous studies have suggested that codon usage in immunoglobulin variable (V) region genes is such that the sequence-specificity of somatic hypermutation results in greater mutability in complementarity-determining regions of the gene than in the framework regions. We have developed a new resampling-based methodology to explore genetic plasticity in individual V genes and in V gene families in a statistically meaningful way. We determine what factors contribute to this mutability difference and characterize the strength of selection for this effect. We find that although the codon usage in immunoglobulin V genes renders them distinct among translationally equivalent sequences with random codon usage, they are nevertheless not optimal in this regard. We find that the mutability patterns in a number of species are similar to those we find for human sequences. Interestingly, sheep sequences show extremely strong mutability differences, consistent with the role of somatic hypermutation in the diversification of primary antibody repertoire in these animals. Human TCR Vβ sequences resemble immunoglobulin in mutability pattern, suggesting one of several alternatives, that hypermutation is functionally operating in TCR, that it was once operating in TCR or in the common precursor of TCR and immunoglobulin, or that the hypermutation mechanism has evolved to exploit the codon usage in immunoglobulin (and fortuitously, TCR) rather than vice-versa. Our findings provide support to the hypothesis that somatic hypermutation appeared very early in the phylogeny of immune systems, that it is, to a large extent, shared between species, and that it makes an essential contribution to the generation of the antibody repertoire.

Affinity maturation is a distinctive feature of immune responses in endothermic species such as mice and humans. During a period of 2-3 weeks after immunization, the affinity of antibodies that are raised in response to the immunogen (the molecules in the inoculum that trigger the immune response) increases by 1–3 orders of magnitude. This is due to a miniature evolutionary process involving the cells (B cells) that secrete antibody molecules. The process takes place in the specialized microenvironment of the germinal centers (Jacob et al. 1991), in which B cells replicate at considerable rates (Hanna 1964; Zhang et al. 1988; Liu et al. 1991). Mutations are introduced in the variable regions of B-cell receptors (also known as antibodies, or immunoglobulins) engaged in the response, at a rate 105–106 times higher than background DNA mutation (Weigert et al. 1970; Bernard et al. 1978), therefore this mutational process is called somatic hypermutation. The affinity of B-cell receptors for immunogen constitutes the basis on which the cells are selected and recruited for the memory compartment. Memory B cells generally carry high-affinity receptors, in contrast to the B cells involved in the early stages of the immune response whose receptors were unmutated (Berek et al. 1991; Jacob and Kelsoe 1992; Nossal 1992). The nature of somatic hypermutation is not known, but there is a wealth of knowledge about its sequence specificity (Lebecque and Gearhart 1990; Rogozin and Kolchanov 1992; Betz et al. 1993; Smith et al. 1996; Dörner et al. 1998; Milstein et al. 1998). Certain nucleotide motifs have been shown to be preferentially mutated, and are thus called hot spots. In most systems in which somatic hypermutation of B-cell receptors has been described (Wilson et al. 1992; Betz et al. 1993; Hinds-Frey et al. 1993; Van der Stoep et al. 1993; Reynaud et al. 1995), the sequence specificity seems to follow similar patterns.

The genes encoding the light and heavy chains of the antibody molecule, as well as the α and β chains of the T-cell receptor (TCR), are assembled through a somatic rearrangement process from a number of gene fragments (Tonegawa 1983). These fragments are V (variable), D (diversity, only present in immunoglobulin heavy chains and TCR β chains), J (junctional), and C (constant). A number of nonidentical copies for each type of fragment are present in the genome, constituting what are called libraries of functionally identical gene fragments. A given B cell bears only one type of antibody (heavy and light chain) on its surface, but different B cells may have different receptors. During the folding process of the antibody heavy and light chains, regions that are not contiguous in the primary structure, come in close proximity to form the binding site. These regions are called complementarity-determining regions (CDR), and they alternate, in the primary structure of the protein, with framework regions (FR). As opposed to CDR, which participate in the immunogen binding, FR are essential for the correct folding of the antibody.

The diversity of CDR translates into a diversity of binding sites, and is therefore an essential ingredient in the ability of the immune system to respond to a wide variety of pathogens. Tanaka and Nei (1989) presented evidence for diversity-enhancing selection operating on the CDR. Although we believe that germ-line diversity is very important, it is also limited, and it seems plausible that the survival ability of the organism grows only slowly as a function of the size of its primary antibody repertoire (Oprea and Forrest 1999). In this study, we argue that CDR are not only diverse, but they are also readily diversifiable under somatic hypermutation, a property that will be referred to as plasticity. In contrast, framework regions are not only more conserved in evolution, but are also less likely to undergo somatic hypermutation.

That CDR are inherently more susceptible to (somatic) mutations has been suggested by various authors (Motoyama et al. 1991; Varade et al. 1993), and later supported by statistical evidence (Wagner et al. 1995; Kepler 1997; Dörner et al. 1998; Cowell et al. 1999). In this study, we develop a novel resampling-based methodology and use it to analyze several aspects of this genetic plasticity. We show that individual V gene fragments evolved codon bias that enhances their plasticity under somatic hypermutation, and also, that the strength of this effect varies between different V gene families. On the basis of the plasticity patterns that we find, we argue that the mechanism of somatic hypermutation is likely to be shared between a large number of species, and we discuss the possibility of TCR hypermutation (Zheng et al. 1994; Cheynier et al. 1998).

RESULTS

Statistical Analysis on the Level of Individual Sequences

One of the factors limiting previous analyses of mutability differences in immunoglobulin sequences is the small number of effectively independent sites for making the appropriate comparisons. There are just a handful of codons in the CDR of any given immunoglobulin V gene, and the effect in which we are interested may be subtle enough that this limit on the sample size sharply reduces the power of any tests based on individual sequences. Furthermore, related sequences are not independent, so one is limited in the ways one can use information from such collections of related sequences (Kepler 1997). Our approach is quite different. To understand the mutability pattern of a given V-gene sequence we compare it with those of a large population of artificial sequences constructed by resampling of the original sequence according to various resampling schemes (see Methods). In this way, we are able to make statistically meaningful statements about individual sequences.

For each V region sequence, we calculate the following quantities: the average replacement mutability per FR nucleotide (μF), the average replacement mutability per CDR nucleotide (μC), and the CDR/FR mutability ratio (μC/μF). Each of the resampled, artificial sets preserves one particular structural feature of the actual gene (for details see the Methods section). The information regarding one gene sequence is graphically represented as follows. Each artificial variant of the sequence is characterized by two numbers, its predicted mean FR and CDR mutabilities. After collecting measurements over many artificial variants, we construct a histogram of the counts on these two numbers and display it as a contour plot in the plane of CDR versus FR mutabilities. By plotting these histograms for different artificial datasets along with the CDR and FR mean mutabilities for the actual sequence, we can see how these artificial sets relate to each other as well as where, within the range of variability for each artificial set, the actual sequence falls. Using this approach, we attempt a more detailed understanding of the selection pressures that operate individual genes.

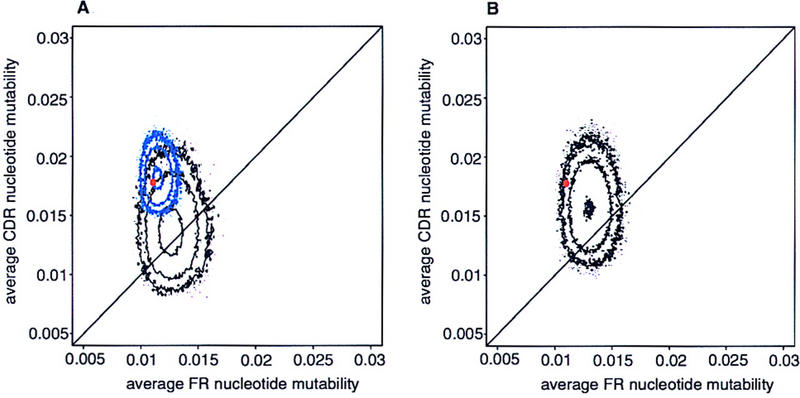

For the purpose of illustration, we take the human heavy chain gene VH6-1, the sole member of the 6th VH family. We find that the average replacement mutability of a CDR nucleotide in VH6-1 is 1.6 times higher than the average replacement mutability of a FR nucleotide, consistent with the findings of Insel and Varade (1998). In addition, we provide information about the structural features underlying the CDR/FR mutability difference of this gene. Figure 1 shows several things; first the nucleotide composition alone could not be responsible for the difference (the black contour plot lies on the diagonal of identical CDR/FR mutability). Furthermore, the position of the observed VH6-1 (red dot) lies above and to the left of the contour of artificial sequences with the same CDR and FR nucleotide composition. This indicates that nearest-neighbor interactions both decrease the FR mutability and enhance the CDR mutability relative to the the bulk of artificial sequences with identical nucleotide composition.

Figure 1.

Contour plot of the predicted average FR vs. CDR mutability of VH6-1 variants: (A) 105 sequences identical nucleotide composition (black), 105 sequences with similar codon composition (blue); (B) 105 sequences with identical amino acid translation (black). The contour levels are drawn at 1, 10, and 100 sequences. The actual gene is shown in red.

To determine what features of these interactions are most responsible for this effect, we turn to artificial sequences that preserve the codon composition of the actual sequence, but do not preserve the context of the codons. That is to say, all the codons of the actual sequence appear in the artificial sequence, although in a different order. What we find is that the contour plot of these artificial sequences (Fig. 1A, blue) is strongly displaced up and/or to the left of the diagonal line on which FR and CDR mutabilities are equal; CDR mutability is increased and/or FR mutability is decreased. Furthermore, the real sequence falls quite close to the center of the distribution, indicating that the inter-codon interactions are not playing a significant role in the plasticity of this gene (Table 1). In other words, the highly degenerate third codon position does not seem to be chosen for its influence on its 3′ neighbor (first position in the next codon).

Table 1.

Quantiles of Individual Real VHSequences Within Each of the Three Variant Sets Generated by Resampling

| Gene | Nucleotide permutations | Codon permutations | Translationally equivalent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μF | μC | μC/μF | μF | μC | μC/μF | μF | μC | μC/μF | |

| Human VH1 genes | |||||||||

| IGHV1–18 | 0.783 | 0.976 | 0.914 | 0.396 | 0.074 | 0.134 | 0.154 | 0.536 | 0.729 |

| IGHV1–2 | 0.725 | 0.776 | 0.662 | 0.582 | 0.168 | 0.17 | 0.093 | 0.107 | 0.331 |

| IGHV1–24 | 0.617 | 0.225 | 0.207 | 0.236 | 0.11 | 0.184 | 0.0745 | 0.6 | 0.797 |

| IGHV1–3 | 0.861 | 0.92 | 0.783 | 0.639 | 0.078 | 0.077 | 0.287 | 0.478 | 0.598 |

| IGHV1–45 | 0.896 | 0.84 | 0.66 | 0.735 | 0.241 | 0.177 | 0.351 | 0.118 | 0.175 |

| IGHV1–46 | 0.805 | 0.969 | 0.898 | 0.134 | 0.359 | 0.566 | 0.191 | 0.709 | 0.824 |

| IGHV1–58 | 0.815 | 0.779 | 0.637 | 0.474 | 0.477 | 0.485 | 0.221 | 0.552 | 0.65 |

| IGHV1–69 | 0.878 | 0.885 | 0.731 | 0.49 | 0.561 | 0.563 | 0.19 | 0.787 | 0.863 |

| IGHV1–8 | 0.837 | 0.47 | 0.313 | 0.257 | 0.07 | 0.142 | 0.154 | 0.137 | 0.292 |

| IGHV1–f | 0.931 | 0.8 | 0.547 | 0.66 | 0.187 | 0.163 | 0.344 | 0.529 | 0.61 |

| Human VH2 genes | |||||||||

| IGHV2–26 | 0.549 | 0.177 | 0.193 | 0.445 | 0.04 | 0.082 | 0.034 | 0.783 | 0.943 |

| IGHV2–5 | 0.463 | 0.484 | 0.508 | 0.548 | 0.317 | 0.311 | 0.014 | 0.742 | 0.94 |

| IGHV2–70 | 0.426 | 0.571 | 0.599 | 0.365 | 0.243 | 0.343 | 0.007 | 0.907 | 0.991 |

| Human VH3 genes | |||||||||

| IGHV3–11 | 0.74 | 0.95 | 0.872 | 0.564 | 0.762 | 0.717 | 0.055 | 0.922 | 0.977 |

| IGHV3–13 | 0.829 | 0.866 | 0.725 | 0.906 | 0.477 | 0.284 | 0.42 | 0.776 | 0.79 |

| IGHV3–15 | 0.592 | 0.554 | 0.498 | 0.415 | 0.192 | 0.238 | 0.24 | 0.61 | 0.708 |

| IGHV3–16 | 0.159 | 0.216 | 0.397 | 0.472 | 0.286 | 0.307 | 0.019 | 0.579 | 0.826 |

| IGHV3–19 | 0.227 | 0.221 | 0.364 | 0.507 | 0.294 | 0.308 | 0.061 | 0.564 | 0.76 |

| IGHV3–20 | 0.178 | 0.363 | 0.555 | 0.516 | 0.07 | 0.081 | 0.018 | 0.6 | 0.895 |

| IGHV3–21 | 0.481 | 0.995 | 0.987 | 0.504 | 0.787 | 0.752 | 0.03 | 0.991 | 0.999 |

| IGHV3–23 | 0.815 | 0.953 | 0.858 | 0.721 | 0.322 | 0.256 | 0.126 | 0.941 | 0.971 |

| IGHV3–30.3 | 0.766 | 0.849 | 0.687 | 0.678 | 0.438 | 0.371 | 0.088 | 0.956 | 0.987 |

| IGHV3–30 | 0.679 | 0.752 | 0.634 | 0.608 | 0.576 | 0.515 | 0.097 | 0.938 | 0.975 |

| IGHV3–33 | 0.594 | 0.862 | 0.789 | 0.606 | 0.542 | 0.488 | 0.026 | 0.916 | 0.984 |

| IGHV3–35 | 0.254 | 0.211 | 0.342 | 0.367 | 0.279 | 0.345 | 0.037 | 0.571 | 0.799 |

| IGHV3–38 | 0.523 | 0.819 | 0.785 | 0.37 | 0.224 | 0.294 | 0.039 | 0.856 | 0.954 |

| IGHV3–43 | 0.388 | 0.731 | 0.753 | 0.467 | 0.367 | 0.393 | 0.058 | 0.867 | 0.961 |

| IGHV3–47 | 0.614 | 0.981 | 0.952 | 0.434 | 0.715 | 0.727 | 0.131 | 0.986 | 0.994 |

| IGHV3–48 | 0.76 | 0.995 | 0.966 | 0.663 | 0.924 | 0.864 | 0.136 | 0.995 | 0.997 |

| IGHV3–49 | 0.627 | 0.888 | 0.815 | 0.678 | 0.096 | 0.09 | 0.204 | 0.767 | 0.854 |

| IGHV3–53 | 0.495 | 0.983 | 0.97 | 0.341 | 0.527 | 0.605 | 0.022 | 0.878 | 0.975 |

| IGHV3–64 | 0.77 | 0.955 | 0.872 | 0.734 | 0.447 | 0.356 | 0.177 | 0.955 | 0.971 |

| IGHV3–66 | 0.629 | 0.978 | 0.944 | 0.395 | 0.479 | 0.533 | 0.059 | 0.899 | 0.967 |

| IGHV3–7 | 0.741 | 0.759 | 0.603 | 0.737 | 0.516 | 0.411 | 0.071 | 0.89 | 0.962 |

| IGHV3–72 | 0.197 | 0.966 | 0.977 | 0.269 | 0.686 | 0.77 | 0.038 | 0.893 | 0.979 |

| IGHV3–73 | 0.504 | 0.967 | 0.943 | 0.656 | 0.53 | 0.456 | 0.022 | 0.863 | 0.969 |

| IGHV3–74 | 0.555 | 0.957 | 0.92 | 0.657 | 0.635 | 0.552 | 0.063 | 0.971 | 0.992 |

| IGHV3–9 | 0.306 | 0.813 | 0.848 | 0.639 | 0.258 | 0.226 | 0.036 | 0.966 | 0.994 |

| IGHV3–d | 0.574 | 0.742 | 0.692 | 0.383 | 0.226 | 0.291 | 0.124 | 0.82 | 0.909 |

| Human VH4 genes | |||||||||

| IGHV4–28 | 0.415 | 0.936 | 0.923 | 0.293 | 0.357 | 0.489 | 0.001 | 0.59 | 0.933 |

| IGHV4–301 | 0.625 | 0.964 | 0.923 | 0.35 | 0.005 | 0.049 | 0.031 | 0.472 | 0.779 |

| IGHV4–302 | 0.545 | 0.79 | 0.751 | 0.228 | 0.034 | 0.121 | 0.019 | 0.493 | 0.775 |

| IGHV4–304 | 0.477 | 0.971 | 0.952 | 0.254 | 0.009 | 0.095 | 0.01 | 0.63 | 0.912 |

| IGHV4–31 | 0.64 | 0.962 | 0.918 | 0.336 | 0.006 | 0.05 | 0.041 | 0.466 | 0.76 |

| IGHV4–34 | 0.359 | 0.837 | 0.851 | 0.146 | 0.224 | 0.427 | 0.006 | 0.686 | 0.931 |

| IGHV4–39 | 0.424 | 0.993 | 0.984 | 0.312 | 0.459 | 0.577 | 0.006 | 0.806 | 0.976 |

| IGHV4–4 | 0.245 | 0.985 | 0.986 | 0.294 | 0.7 | 0.767 | 0.001 | 0.644 | 0.961 |

| IGHV4–59 | 0.308 | 0.977 | 0.975 | 0.236 | 0.22 | 0.406 | 0.003 | 0.543 | 0.907 |

| IGHV4–61 | 0.31 | 0.992 | 0.99 | 0.227 | 0.125 | 0.327 | 0.003 | 0.76 | 0.972 |

| IGHV4–b | 0.31 | 0.987 | 0.985 | 0.127 | 0.192 | 0.461 | 0.004 | 0.685 | 0.953 |

| IGHV5–51 | 0.791 | 0.996 | 0.977 | 0.599 | 0.934 | 0.903 | 0.065 | 0.917 | 0.975 |

| IGHV5–a | 0.888 | 0.997 | 0.967 | 0.596 | 0.938 | 0.901 | 0.21 | 0.975 | 0.981 |

| Human VH6 gene | |||||||||

| IGHV6–1 | 0.041 | 0.966 | 0.994 | 0.214 | 0.356 | 0.573 | 0.008 | 0.855 | 0.987 |

| Human VH7 genes | |||||||||

| IGHV7–41 | 0.453 | 0.886 | 0.869 | 0.24 | 0.131 | 0.264 | 0.012 | 0.193 | 0.601 |

| IGHV7–81 | 0.893 | 0.515 | 0.319 | 0.522 | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.26 | 0.015 | 0.043 |

The encoding of some amino acids is doubly or even singly degenerate, whereas others are three-, four-, or sixfold degenerate. The latter are naturally less susceptible to replacement mutations than the former. It is conceivable that the amino acid sequence of CDR is enriched in amino acids that are more susceptible to replacement mutations purely by virtue of their degeneracy (Chang and Casali 1994). To test this hypothesis, we generated artificial sequences that have the same amino acid translation as the actual sequence, but use different codons to encode these amino acids. Figure 1B (black contour) shows that if codon usage were random, CDR would, on average, be somewhat more mutable than FR, but the real sequence is significantly different from these artificial variants (Table 1). This indicates that, although detectable, the effect of amino acid usage is considerably enhanced by the specific codon usage of the actual gene.

In humans, there are seven families of heavy chain V-region sequences (Max 1998) with different apparent functionality, V-gene usage varies with the specific immunogen, and perhaps with other characteristics of the infection as well. Therefore, it may be of some interest to compare the plasticity of VH families. Table 1 shows there is considerable variation in plasticity between VH families. For each actual gene, we determined the quantile of the indicated statistic (μF, μC, μCrtificial sequence sets. Relative to the translationally equivalent var/μF) within each group of resampled aiants, the mutability ratio is high for all VH families except VH1 and VH7. VH5 has an especially high CDR mutability, whereas VH2, VH4, and VH6 have low FR mutability. In VH3 genes, we observe both low FR mutability as well as high CDR mutability.

Analysis of V-Gene Alignments

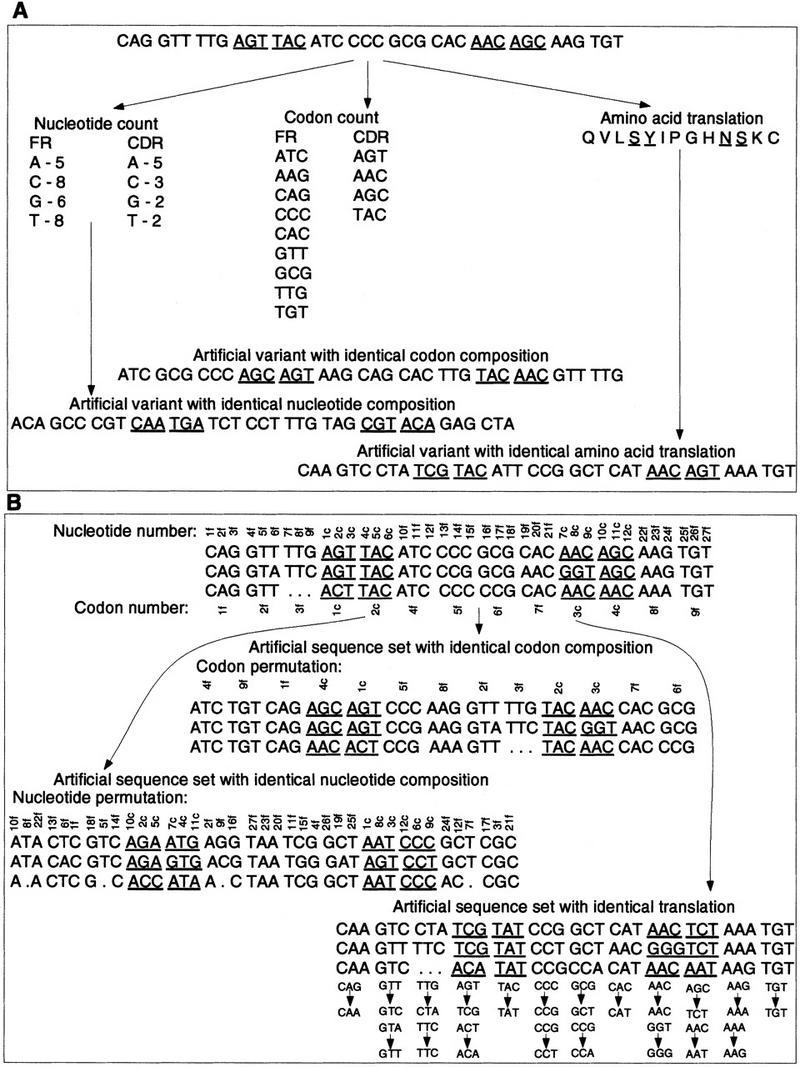

Because immunoglobulin V genes are related through common ancestry, we expect that their mutabilities will be correlated. Therefore, we adapted the foregoing tests for use on sequence alignments rather than on individual genes, obviating the problem of correlations (see Methods and Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Sketch of the algorithm for generating artificial variants of (A) individual gene sequences. The nucleotides in FR and CDR are pooled separately. An artificial sequence is then constructed by sampling, without replacement from the pool of FR and CDR, respectively. Similarly, FR and CDR codons are separately pooled. To construct the FRs and CDRs of an artificial variant, FR and CDR codons are sampled, without replacement, from the respective pools of codons. Finally, the gene sequence is translated into the amino acid sequence. Then, for each amino acid position, one of the possible synonymous codons is chosen, with uniform probability for the artificial variant. (B) A family of gene sequences. The nucleotide positions in the alignment are numbered separately for FRs and CDRs. A permutation of these indices is generated and used to construct a complete artificial set of sequences. Then, the codon sites in the alignment are numbered, the indices permuted, and the permutation used to construct variant sequence sets with identical codon composition. Finally, the sequences are aligned and translated. At each amino acid position in the alignment, a new set of permutations over each of the synonymous codons is generated. The alignment is then traversed, and an artificial set of sequences is constructed by replacing the codon that appears in the real gene at that position with the one corresponding to it in the permutation.

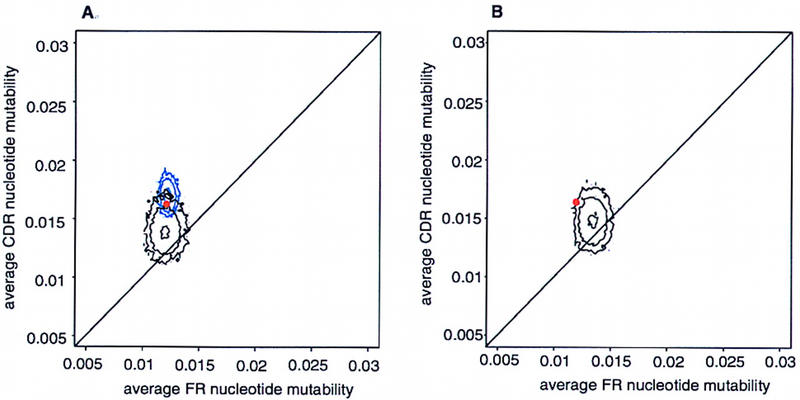

Contour plots of the replacement mutability per FR and CDR nucleotide averaged over positions within each gene and over genes within the alignments for the three types of artificial variants of the human VH sequence set as shown in Figure 3. We find a small effect of nucleotide composition (Padlan 1997), as well as of amino acid composition on the CDR/FR mutability difference. What we have been able to show in this study is that, by far, the most important single factor in differential mutability is the different codon usage of the two types of regions. We infer this from both the placement of the artificial sequence sets in the plane of CDR–FR set average mutability, and from the position of the actual VH genes relative to the artificial sequence sets. These results can again be partially summarized by the quantiles of the real gene set within each of its resampled variants (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Contour plot of the average FR vs. CDR mutability over sets of artificial variants of human VH sequences. We constructed (A) 104 sets with identical nucleotide composition (black), 104 sets with identical codon composition (blue), and (B) 104 sets with identical amino acid translation (black). The contour levels are drawn at 1, 10, and 100 sequences. The actual sequence set is shown in red.

Table 2.

Quantiles of Complete Human VH Alignment Within Each of the Three Variant Sets Generated by Resampling

| Nucleotide permutations | Codon permutations | Translationally equivalent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μF | μC | μF/μF | μF | μC | μC/μF | μF | μC | μC/μF |

| 0.623 | 0.9925 | 0.961 | 0.425 | 0.161 | 0.244 | 0.006 | 0.957 | 0.998 |

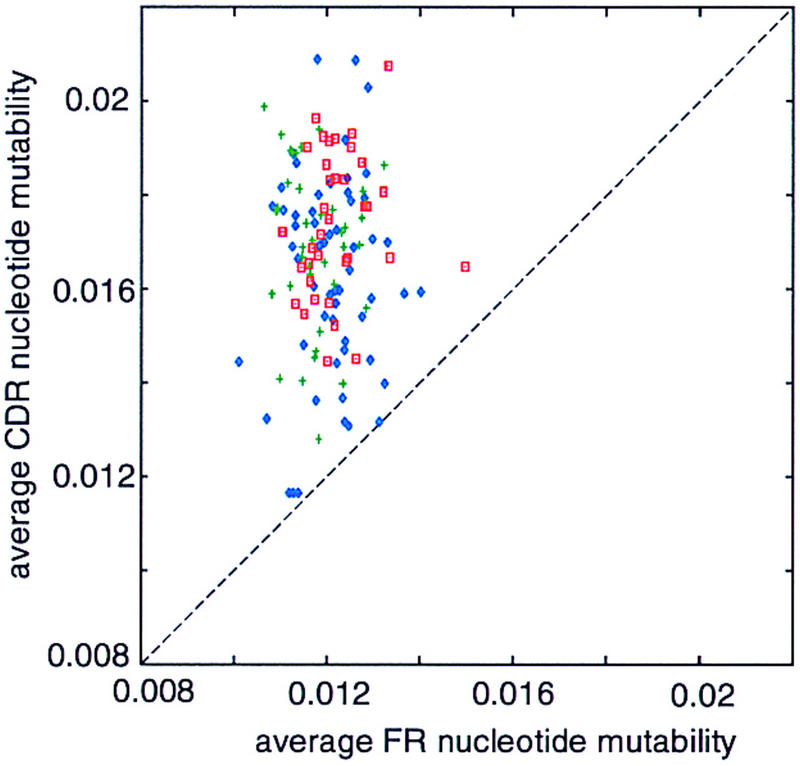

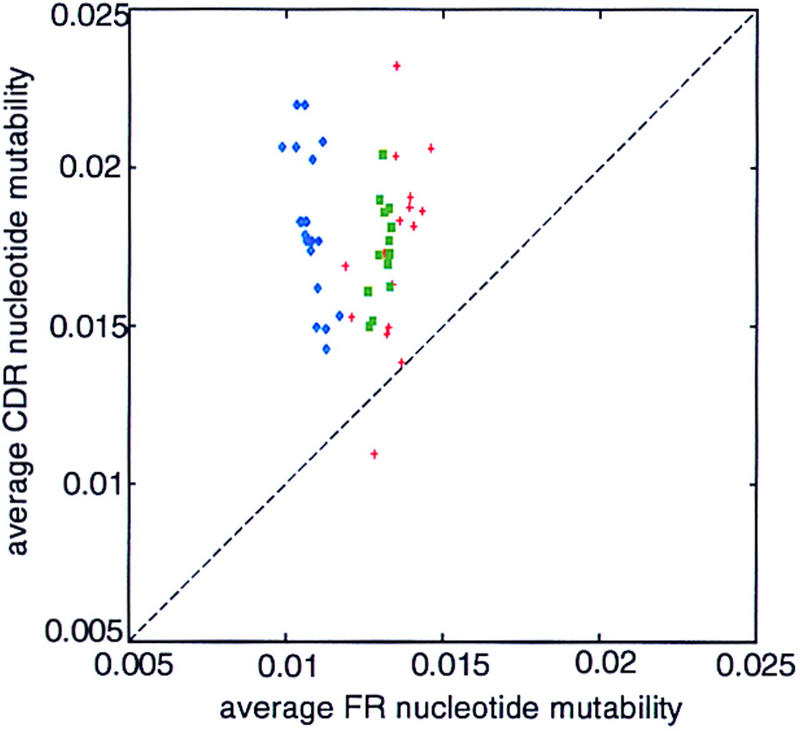

We examined the human Vκ and Vλ gene segments in a similar manner. We find that all of these sequences have higher replacement mutability of CDR nucleotides than of FR nucleotides (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of the predicted average mutability per FR vs. CDR nucleotide for the set of 56 human VH (blue), 39 Vλ (green), and 37 Vκ (red) sequences.

Are Human V Region Genes Locally Optimized for Somatic Hypermutation?

Having shown that selection for plasticity under somatic hypermutation is evident in individual V genes, we may ask whether these sequences appear to be locally optimal with respect to this property. That is, are these gene segments better than the sequences obtained by replacing a small number of nucleotides while preserving the translation?

To address this question, we use artificial sequences that differ from the real sequence by a small number of silent mutations. Among the 2-mutation neighbors, the proportion of sequences with higher CDR/FR mutability ratio than the actual sequence varies between 38 and 52 percent. Among 10-mutation neighbors, this proportion varies more widely (25% to 65%). By the time we reach 50-mutation neighbors, the V gene family-specific patterns that we discussed above (see also Table 1) begin to emerge. We conclude that although local codon bias clearly enhances the CDR/FR mutability ratio in human VH genes, this differential codon bias is far from fully optimal for plasticity under somatic hypermutation.

Phylogenetic Analysis of V-Gene Plasticity

We analyzed two other complete germ-line sequence sets, sheep (Ovis aries) Vλ and rainbow trout (Oncorhyncus mykiss) VH, a (possibly incomplete) germ-line set of VH sequences from horned shark (Heterodontus franciscii), and a set of cDNA VH sequence of African clawed toad (Xenopus laevis). We find that CDR mutability is higher than FR mutability in these sequences, similar to human sequences (Fig. 5). Moreover, we also find codon usage consistent with low FR and high CDR mutability (Table 3). This suggests not only that these genes, too, have enhanced plasticity, but that the microsequence specificity is sufficiently well conserved that such patterns are evident even though the mutability model was inferred from murine data (see Methods). The average CDR/FR mutability ratio of the actual sequence set is always very high relative to translationally equivalent variant sets, and in one case, of the sheep Vλ, none of the variant sequence sets had as high a ratio as the actual set. A detailed analysis of individual Vλ genes of sheep is presented in Table 4. Both FR and CDR codon bias contribute to the high mutability ratio in a seemingly complementary manner. The CDR codon bias is more extreme in the species in which the FR codon bias is relatively low (rainbow trout) or absent (African toad).

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of the predicted average replacement mutability of CDR vs. FR nucleotides for: sheep Vλ (blue), horned shark VH (green), rainbow trout VH (red).

Table 3.

Quantiles of FR and CDR Mutability and CDR/FR Mutability Ratio of the Real Sequence Sets Compared to Translationally Equivalent Variants in Various Species

| Species | Serine included | Serine excluded | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μF | μC | μC/μF | μF | μC | μC/μF | |

| Human VH | 0.006 | 0.957 | 0.998 | 0.002 | 0.57 | 0.744 |

| Sheep Vλ | 0.001 | 0.976 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.14 | 0.687 |

| Rainbow trout VH | 0.1 | 0.983 | 0.994 | 0.007 | 0.325 | 0.805 |

| Horned Shark VH | 0.047 | 0.675 | 0.974 | 0.022 | 0.787 | 0.983 |

| African toad VH | 0.423 | 0.991 | 0.985 | 0.499 | 0.561 | 0.546 |

Table 4.

Quantiles of Individual Sheep Vλ Sequences

| Gene | Translationally equivalent variants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| μF | μC | μC/μF | |

| SHPIGJVB | 0.003 | 0.911 | 0.992 |

| AF040900 | 0.002 | 0.987 | 1 |

| AF040901 | 0.01 | 0.999 | 1 |

| AF040902 | 0.004 | 0.976 | 0.998 |

| AF040904 | 0.031 | 0.427 | 0.685 |

| AF040905 | 0.005 | 0.999 | 1 |

| AF040907 | 0.002 | 0.975 | 0.999 |

| AF040908 | 0.003 | 0.87 | 0.982 |

| AF040909 | 0.015 | 0.673 | 0.919 |

| AF040911 | 0.007 | 0.913 | 0.988 |

| AF040913 | 0.006 | 0.804 | 0.96 |

| AF040914 | 0.022 | 0.995 | 1 |

| AF040915 | 0.008 | 0.978 | 0.998 |

| AF040916 | 0.019 | 0.673 | 0.909 |

| AF040917 | 0.001 | 0.91 | 0.991 |

| AF040918 | 0.001 | 0.976 | 0.999 |

| AF040919 | 0.01 | 0.672 | 0.932 |

| AF040920 | 0.014 | 0.674 | 0.921 |

| AF040921 | 0.006 | 0.288 | 0.745 |

| AF040922 | 0.013 | 0.701 | 0.914 |

| AF040923 | 0.001 | 0.975 | 0.999 |

| AF040924 | 0.003 | 0.975 | 0.998 |

We performed a similar test on a number of isolated sequences ranging from the new antigen receptor (Greenberg et al. 1995) of the nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) and short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica), to the heavy chain dimers of the camel (Camelus dromedarius). High CDR relative to FR mutability is a general characteristic in almost all of the sequences that we analyzed (data not shown).

Relation Between Serine Codon Usage and Mutability

To determine the role that serine codon segregation plays in the mutability of the two regions of the V genes, we repeated the above analyses, disregarding the nucleotides that encode serine in the calculation of mutability. In human VH, sheep Vλ, and rainbow trout VH, we find that codon bias at amino acids other than serine induces very low FR mutability. The CDR/FR mutability ratio remains high in the real sequence sets, even though for most of these sets, the CDR mutability becomes indistinguishable from that of translationally equivalent variants. The mutability of horned shark VH is almost unaffected by serines, whereas the CDR/FR mutability difference of African toad sequences seems to be due entirely to the presence of the highly mutable serine codons in the CDR. These results are summarized in Table 3.

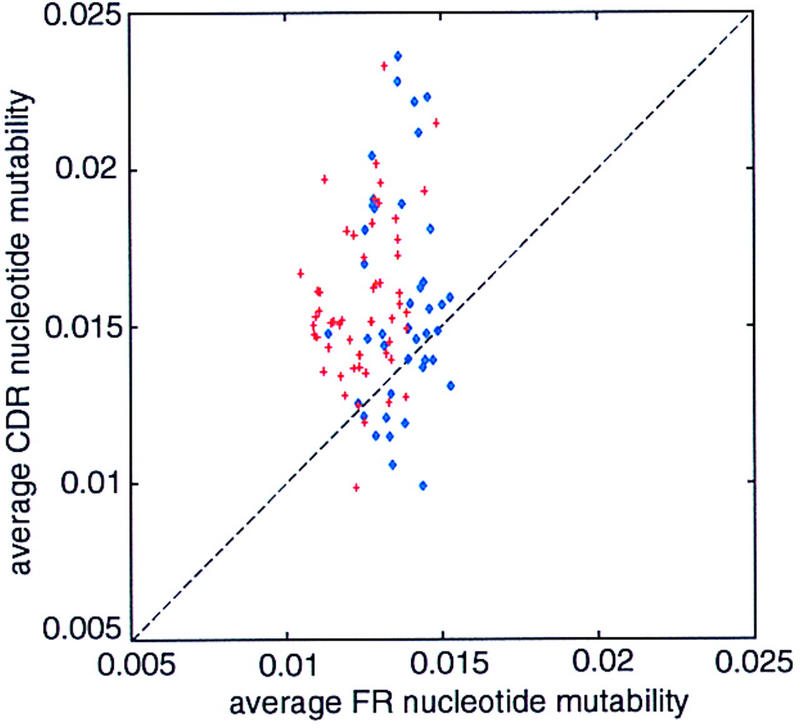

Higher Predicted Replacement Mutability of TCR CDR Than of TCR FR

Because the trace of somatic hypermutation is so apparent in immunoglobulin genes by use of our analytical methods, we attempted a similar analysis of TCR sequences, hoping to shed more light on the still-controversial issue of TCR hypermutation. Figure 6 shows the scatter plot of the average FR–CDR nucleotide mutability of TCRα (blue) and TCRβ (red) V region genes. For most of TCRβ sequences, we predict higher replacement mutability of their CDR nucleotides than of their FR nucleotides. For TCRα this difference is not as clear, many sequences having lower mutability in the CDR than in the FR. We find very strong evidence for plasticity enhancement in TCRβ, but not in TCRα (Table 5).

Figure 6.

Scatter plot of the predicted FR vs. CDR nucleotide mutability values for the set of human TCRα (blue) and TCRβ (red) sequences.

Table 5.

Quantiles of Germ-Line TCR Gene Alignments with Respect to their Translationally Equivalent Variants

| Sequence set | μF | μC | μC/μF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCRα | 0.352 | 0.394 | 0.444 | |

| TCRβ | 0.01 | 0.958 | 0.989 |

DISCUSSION

It is usually quite difficult to construct a complete account of the evolutionary process in molecular detail, because the mapping from genotype to phenotype is generally too complex to determine fully. A remarkable feature of the system studied here, the evolution of immunoglobulin variable region genes under the pressures caused by somatic hypermutation, is that the phenotypic trait of plasticity under somatic hypermutation can be mapped to the genotype very satisfactorily. This is so because the trait is a property of the DNA sequences themselves, and not of their products.

There remain, of course, those traits of the immunoglobulins that are expressed in the protein molecules themselves. Ironically, perhaps, the map from genotype to protein phenotype in immunoglobulins is even more complex than usual due to the extensive somatic modification that is required for expression. Thus, plasticity under somatic hypermutation—the ability to put mutations in CDR, in which they have a higher chance of enhancing function and away from FR, in which they have a higher chance of disrupting function—although potentially having only subtle effects, may, by virtue of its directness, be a primary force in the formation of the germ-line V-gene repertoire.

We have undertaken a detailed study of V-gene plasticity at the level both of individual genes and of gene families.

What Determines the CDR/FR Mutability Difference in Human VH Genes?

Consistent with the results of Padlan (1997), we found that the difference in nucleotide composition accounts, to some extent, for the difference in mutability. There are, however, important local interactions, codon bias makes FR significantly less mutable than their translationally equivalent variants, the converse being true for the CDR. The high mutability in CDR is due largely to local bias in the use of serine codons. Once this segregation is taken into account, CDR are not unusual relative to their translationally equivalent variants sampled without codon bias. This is not to say that AGY serine codons are entirely responsible for the high CDR mutability. Highly mutable amino acids (i.e., amino acids with low degeneracy in their encoding, as well as amino acids for which all codons have relatively high mutability) maintain a high CDR mutability independently of the serine codons.

Serine is a peculiar amino acid in the following sense. For all other amino acids, the synonymous codons are mutually accessible via single-point mutations. In contrast, serine is encoded by two mutually isolated codon sets, AGY and TCN. The largest differences in mutability among synonymous codons are those between these two disjoint serine codon sets. Thus, the preferential use of the mutable AGY codons in CDR and of the less mutable TCN codons in FR, and the resulting high CDR/FR mutability ratios, are difficult to interpret. Is the observed segregation due to selection for plasticity under somatic hypermutation, or are the two different types of serine codons frozen accidents and the apparent mutability differences merely artifactual? The results that we obtained on horned shark VH are very interesting to us from this perspective. The shark is phylogenetically the oldest species that we have in our data set. In fact, the vertebrate immune system arose with jawed vertebrates, that is, with sharks or their immediate ancestors (Du Pasquier and Flajnik 1998). We found that in this species, the CDR and FR mutabilities are almost unaffected by serines. In other words, the mutability pattern that we are studying already exists in the oldest known immunoglobulin genes, and is not due to the segregation of more mutable serine codons in the CDR.

Human VH families differ in their mutability pattern, but in the absence of greater understanding of the functional role of these genes, we are not able to interpret these results.

Is the Somatic Hypermutation Mechanism Shared Between Mammals and Poikilothermic Vertebrates?

The mechanism responsible for somatic hypermutation in mammals may differ from that of poikilothermic vertebrates such as nurse shark (Hinds-Frey et al. 1993) and African toad (Wilson et al. 1992; Hsu 1998). This issue has not yet been resolved, but our results may be relevant here. We detected differential codon bias associated with high CDR and low FR mutability in these poikilothermic species. For us to see these patterns with our methods, not only must these species be subject to selection for V-gene plasticity as are humans and mice (the patterns have to be there) but the microsequence specificity of the somatic hypermutation mechanism must be similar to those found in mouse (the source of our estimates for the mutation model). This is what we found, with the possible exception of the African toad sequences (with the caveat that these were cDNA rather than germ-line sequences and might already contain somatic mutations). These results argue for the ubiquity of at least some components of the somatic hypermutation mechanism. If the mechanism of somatic hypermutation shares biochemical features with the mechanisms underlying general meiotic mutation, as seems to be the case (M. Oprea and T.B. Kepler, in prep.), this conservation is not surprising.

Although a general mutability pattern did emerge, we also found considerable variability between species. In sheep, somatic hypermutation is used in the diversification of the primary repertoire (Reynaud et al. 1995), presumably without stringent antigen selection. Therefore, these receptors are screened for functionality only after several mutations have been introduced. Under these circumstances, it would seem that the advantage conferred by differential CDR–FR mutability might be much higher in these animals. Interestingly, we found that these genes have very high plasticity. The FR mutability is invariably lower than that of the translationally equivalent variants-regularly in the lowest percentile, and the mutability ratio is extremely high; in four cases, none of the 10,000 synthetic sequences had ratios as high as that observed in the real sequence.

Do TCR Genes Hypermutate?

Although somatic hypermutation has been studied for many years in immunoglobulin V genes, only recently has it been found that TCRs also experience hypermutation (Zheng et al. 1994; Cheynier et al. 1998). The characteristics of T-cell hypermutation are remarkably like those in B cells, only germinal center T cells already recruited into the immune response are mutated. TCR mutations are found in the CDR and particularly in microsequences that are described as hotspots of B-cell receptor hypermutation. Yet, the functional significance of T-cell hypermutation has not been determined, and this part of the story remains controversial. Kepler and Bartl (1998), looking for the presence of mutable motifs in TCR CDR, concluded that some of the TCR chains resemble immunoglobulins in their mutability pattern, but could not provide definitive evidence that TCR sequences are selected for plasticity.

Our analysis of TCR sequences indicates no significant mutability difference between CDR and FR in TCRα. TCRβ, on the other hand, have a mutability pattern similar to those in immunoglobulins. It may be possible that hypermutation does play a functional role in the development of the TCRβ repertoire and is reflected in these genes' differential codon usage. Experimental support for this hypothesis has been provided recently (Cheynier et al. 1998). Alternatively, somatic hypermutation might have been active very early in ontogeny, acting on the ancestral receptor from which both immunoglobulin and TCR evolved. Perhaps somatic mutation was preserved in B cells, but was lost in T cells; the residual codon bias once shared with immunoglobulin carries the trace of the ancient hypermutation mechanism. Although the mutability pattern of immunoglobulins in diverse species also argues for an early origin of somatic mutation, the preservation of a relic local codon bias over long stretches of time in the absence of continued pressure to maintain it strikes us as unlikely. Therefore, we view our results as strong, although indirect, evidence that TCR hypermutation does carry functional significance.

CONCLUSION

It is clear that the hypermutation mechanism (whatever it turns out to be) has coevolved with its substrates. Both the sequence specificity of the mutator and the differential codon usage have likely adapted to each other. Our results are consistent with the mutator having adapted to the codon usage in the primordial antigen receptor with subsequent conservation of both the sequence specificity of the mutator and the codon usage in the V genes. In particular, the suboptimality of V genes in their local sequence neighborhoods and the lack of intercodon interactions (permuting codons within CDR and FR regions does not affect the differential mutability, see Table 1) are most easily accommodated by this perspective.

METHODS

Sequence Data

The sets of human immunoglobulin [H (56 sequences), κ (37 sequences), and λ (39 sequences)] and TCR [α (41 sequences) and β (54 sequences)] V-gene sequences were isolated from IMGT, the international ImMunoGeneTics database (http://imgt.cnusc.fr:8104, Curator: Marie-Paule Lefranc, Montpellier, France lefranc@ligm.igh.cnrs.fr). In cases in which multiple alleles were given for a certain locus, only the first one in the database was considered. As we are only interested in the properties of the germ-line genes, our analysis is restricted to FR1, FR2, FR3, and CDR1, CDR2 fragments. CDR3 is not entirely germ-line encoded, and also receives contribution from multiple gene fragments, therefore it was not included in our analysis. Sheep Vλ(22 sequences) and rainbow trout VH (16) sequences (listed in the IMGT database) were also extracted from GenBank. FR/CDR assignment for these genes was also extracted from IMGT database.

The set of horned shark VH sequences (15) was extracted from GenBank, accession numbers Z11777, Z11778, and Z11780-Z11792, and the set of African toad VH sequences (14) was compiled from the Kabat database, accession numbers KADBID004348, KADBID004350–51, KADBID004353, KADBID004356–57, KADBID004359–61, KADBID004365–66, KADBID004371, KADBID004376, and KADBID004386. Note that this latter set contained cDNA sequences rather than germ-line sequences. The DNA sequences were translated into corresponding amino acid sequences, which were aligned to human VH, by the ClustalW algorithm available on-line from http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw. We used the default parameters for this alignment. The FR/CDR assignment was then inferred from the alignment of protein sequences.

The two known germ-line nurse shark antigen receptor genes were compiled from Roux et al. (1998), with the given FR/CDR assignment, as these sequences have a low degree of homology with the other sequences that we used. The set of VH camel cDNA sequences that form heavy chain dimers was extracted from the Kabat database, accession numbers KADBID022284–KADBID022292 and KADBID022294–KADBID0222300. Three opossum cDNA sequences were generously provided by Dr. Robert Miller, Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. These sequences were translated, aligned to human VH as described above, and the alignment was used to infer the FR/CDR assignments.

Mutability Calculation

Parameters for a mutability model in which the mutability of a nucleotide is a function of its identity and the two flanking nucleotides were inferred as in Kepler (1997). These were used to calculate a predicted average mutability per nucleotide in FR and CDR, respectively. Because selection for FR and CDR functionality operates on the level of the protein sequence, we analyzed the replacement mutability. This quantity expresses the propensity of a nucleotide to undergo a mutation that changes the amino acid sequence of the protein. To calculate it, we need not only the mutability of the nucleotide, but also the probability that it mutates into each of the other three nucleotides. These values were taken from Cowell (1999). The algorithm for calculating of replacement mutability of a given nucleotide in the sequence is the following: (1) From the empirical mutability vector, we retrieve the mutability of the nucleotide, given its identity and the identity of its two neighboring nucleotides; (2) from the empirical transition matrix given in Cowell (1999), we retrieve the probability of each of the three possible substitutions of the nucleotide; (3) each substitution of the original nucleotide by another has a probability 0 or 1 to lead to an amino acid replacement; (4) the predicted replacement mutability at a given nucleotide is given by the product of the mutability of the nucleotide found in the actual sequence at that position, and the sum, over all three possible substitutions, of the product of the probability of the specific substitution and the probability that the given nucleotide substitution leads to an amino acid replacement.

The predicted average replacement mutability of a nucleotide in the sequence is calculated by taking the average over all sites in the sequence of the replacement mutability per site. We determine separately the mutability of FR and CDR sites.

Resampled Sequence Sets

To analyze the structural features that contribute to the mutability of an individual sequence, we constructed a number of artificial variants of this sequence. Each set of variants preserves a certain structural property of the real sequence as follows: nucleotide composition, codon composition, and amino acid translation. Figure 2A illustrates the algorithm for constructing these sets of artificial variants. The size of each set was 105 sequences. Once a set of artificial variants of a real sequence was constructed, we calculated, for each of the artificial sequences, the following quantities: average FR nucleotide mutability, μF; average CDR nucleotide mutability, μC; CDR/FR mutability ratio, μC/μF. The quantile of the real sequence is the proportion of artificial variant sequences with given statistic (μF, μC, μC/μF) less than or equal to that of the real sequence.

The artificial variant sets that we constructed so far for individual sequences cannot be used to test hypotheses about the whole gene locus. The reason is that the V-gene sequences are related through a close genealogical relationship; the data from different starting sequences is thus correlated. We can, nonetheless, design an adaptation of the algorithm presented above for constructing sequence variants, such that correlations in sequence composition among the genes in the set are preserved. The key idea is to work with positions in an alignment of sequences, rather than with positions in individual sequences. The new strategy is illustrated in Figure 2B. For the detailed study of human VH-gene locus, we generated 104 artificial replicates of this sequence set, and for the study of codon bias related to somatic hypermutation in different species, 103 replicates of each sequence set were constructed.

Acknowledgments

M.O. would like to thank Eleen Goldberg, Robert Miller, and Erik van Nimwegen for stimulating discussions. T.B.K. would like to thank Lindsay G. Cowell.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL kepler@stat.ncsu.edu; FAX (919) 515-1909.

REFERENCES

- Berek C, Berger A, Apel M. Maturation of the immune response in the germinal centers. Cell. 1991;67:1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90289-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard O, Hozumi N, Tonegawa S. Sequences of mouse immunoglobulin light chain gene before and after somatic changes. Cell. 1978;15:1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A, Rada C, Pannell R, Milstein C, Neuberger M. Passenger transgenes reveal intrinsic specificity of the antibody hypermutation mechanism: Clustering, polarity and specific hot spots. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:2385–2388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Casali P. The CDR1 sequences of a major proportion of human germline Ig vh sequences are inherently susceptible to amino acid replacement. Immunol Today. 1994;15:367–373. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90175-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheynier R, Henrichwark S, Wain-Hobson S. Somatic hypermutation of the T cell receptor V beta gene in microdissected splenic white pulps from HIV-1-positive patients. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1604–1610. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1604::AID-IMMU1604>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell L, Kim H, Humaljoki T, Berek C, Kepler T. Enhanced evolvability in immunoglobulin V genes under somatic hypermutation. J Mol Evol. 1999;49:23–26. doi: 10.1007/pl00006530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörner T, Brezinschek H, Forster S, Brezinschek R, Farner N, Lipsky P. Delineation of selective influences shaping the mutated expressed human Ig heavy chain repertoire. J Immunol. 1998;160:2831–2841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Pasquier L, Flajnik M. Origin and evolution of the vertebrate immune system. In: Paul W, editor. Fundamental immunology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1998. pp. 605–650. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg A, Avila D, Hughes M, Hughes A, McKinney E, Flajnik M. A new antigen receptor gene family that undergoes rearrangement and extensive somatic diversification in sharks. Nature. 1995;374:168–173. doi: 10.1038/374168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna M. An autoradiographic study of thegerminal center in spleen white pulp during early intervals of the immune response. Lab Invest. 1964;13:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds-Frey K, Nishikata H, Litman R, Litman G. Somatic variation preceeds extensive diversification of germline sequences and combinatorial joining in the evolution of immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity. J Exp Med. 1993;178:815–824. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu E. Mutation, selection, and memory in b lymphocytes of exothermic vertebrates. Immunol Rev. 1998;162:25–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel R, Varade W. Characteristics of somatic hypermutation of human immunoglobulin genes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;229:33–44. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71984-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob J, Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the primary immune response to (4-hydroxy-3-nitropheny) acetyl. II. A common clonal origin for periarteriolar lymphoid sheath-associated foci and germinal centers. J Exp Med. 1992;176:679–687. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.3.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob J, Kelsoe G, Rajewsk K, Weiss U. Intraclonal generation of antibody mutants in germinal centers. Nature. 1991;354:389–392. doi: 10.1038/354389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler T. Codon bias and plasticity in immunoglobulins. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:637–643. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler T, Bartl S. Plasticity under somatic mutation in antigen receptors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;229:149–162. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71984-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebecque S, Gearhart P. Boundaries of somatic mutation in rearranged immunoglobulin genes: 5′ boundary is near the promoter, and 3′ boundary is approximately 1 kb from V(D)J gene. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1717–1727. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Zhang J, Lane PJL, Chan EY-T, MacLennan ICM. Sites of specific B cell activation in primary and secondary responses to T cell-dependent and T cell-independent antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2951–2962. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max E. Immunoglobulin: Molecular Genetics. In: Paul W, editor. Fundamental immunology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1998. pp. 111–182. [Google Scholar]

- Milstein C, Neuberger M, Staden R. Both DNA strands of antibody genes are hypermutation targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:8791–8794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyama N, Okada H, Azuma T. Somatic mutation in constant regions of mouse λ1 light chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:7933–7937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.7933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nossal G. The molecular and cellular basis of affinity maturation in the antibody response. Cell. 1992;68:1–2. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90198-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprea M, Forrest S. Proceedings of the 1999 Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference. 1999. How the immune system generates diversity: Pathogen space coverage with random and evolved antibody libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Padlan E. Does base composition help predispose the complementarity-determining regions of antibodies to hypermutation? Mol Immunol. 1997;34:765–770. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(97)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud C, Garcia C, Weill J. Hypermutation generating the sheep immunoglobulin repertoire is an antigen-independent process. Cell. 1995;80:115–125. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90456-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogozin I, Kolchanov N. Somatic hypermutagenesis in immunoglobulin genes. II. Influence of neighboring base sequences on mutagenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1171:11–18. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90134-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux K, Greenberg AS, Greene L, Strelets L, Avila D, McKinney E, Flajnik M. Structural analysis of the nurse shark (new) antigen receptor (NAR): Molecular convergence of NAR and unusual mammalian immunoglobulins. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:11804–11809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Creadon G, Jena P, Portanova J, Kotzin B, Wysocki L. Di- and trinucleotice target preferences in somatic mutagenesis in normal and autoreactive B cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:2642–2652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Nei M. Positive Darwinian selection observed at the variable region genes of immunoglobulins. Mol Biol Evol. 1989;6:447–459. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 1983;302:575–581. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Stoep N, Van der Linden J, Logtenberg T. Molecular evolution of the human immunoglobulin E response: High incidence of shared mutations and clonal relatedness among VH5 transcripts from three unrelated patients with atopic dermatitis. J Exp Med. 1993;177:99–107. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varade W, Marin E, Kittelberger A, Insel R. Use of the most JH-proximal human Ig H chain V region gene, VH6, in the expressed immune repertoire. J Immunol. 1993;150:4985–4995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Milstern C, Neuberger M. Codon bias targets mutation. Nature. 1995;376:732. doi: 10.1038/376732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigert M, Cesari I, Yonkovitch S, Cohn M. Variability in the light chain sequences of mouse antibody. Nature. 1970;228:1045–1047. doi: 10.1038/2281045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M, Hsu E, Marcuz A, Courtet L, Du Pasquier L, Steinberg C. What limits affinity maturation of antibodies in Xenopus—the rate of somatic mutation or the ability to select mutants? EMBO J. 1992;11:4337–4347. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, MacLennan I, Liu Y-J, Lane P. Is rapid proliferation in B centroblasts linked to somatic mutation in memory B-cell clones? Immunol Lett. 1988;18:297–299. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(88)90178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, Xue W, Kelsoe G. Locus-specific somatic hypermutation in germinal centre T cells. Nature. 1994;372:556–559. doi: 10.1038/372556a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]