ABSTRACT

Background:

Longitudinal quality of life (QoL) was compared for patients with esophageal cancer receiving definitive chemoradiotherapy (CRT) with conventional-dose (CD) vs. high-dose (HD) radiotherapy as used in the RTOG phase III 94–05 trial (Intergroup 0123).

Methods:

Between June 12, 1995, and July 1, 1999, 236 patients with cT1–4NxM0 esophageal cancer were randomized to CD CRT (50.4 Gy and concurrent 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin) vs. HD CRT (64.8 Gy and the same chemotherapy). QoL was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, Head & Neck (version 2) at baseline, after CRT, at 8 months from the start of CRT, and at 1 year.

Results:

Of 218 eligible patients, 166 participated in pretreatment QoL assessments (82 HD, 84 CD). Patients with ≥10% weight loss and Karnofsky Performance Status 60–80 were less likely to participate (P = .02 and P = .002, respectively). Pretreatment characteristics for participating patients were similar in both arms. At CRT completion, 96 patients completed QoL (46 HD, 50 CD) assessment. Total mean QoL was significantly lower in the HD arm (P = .02) and remained lower at 8 and 12 months after the start of CRT, but these values did not reach statistical significance. Change in mean QoL from baseline to each of the three subsequent assessment time points did not differ significantly between the two treatment arms.

Conclusions:

For patients treated with definitive CRT for esophageal cancer, radiation dose escalation to 64.8 Gy does not significantly improve QoL. These results provide additional evidence that radiotherapy to 50.4 Gy should remain the standard of care.

The optimal management of patients with esophageal cancer remains controversial.1 Current treatment modalities include surgical resection, radiotherapy (RT), chemotherapy, and some combination thereof.2–9 Despite therapeutic and technical innovations over the past decade, the overall prognosis for these patients remains poor because of the high incidence of local recurrence and metastatic disease.3–9 In light of this unfortunate reality, treatment choices in this setting especially should be made with an eye toward improving or maintaining the patients' quality of life (QoL). Quality-of-life end points might also be useful in the assessment of novel or intensified therapies and treatment comparisons and could provide guidance to physicians in making future clinical decisions and trial design.10,11

Health-related QoL is a multidimensional construct, best assessed prospectively from the patient's point of view. Core QoL domains include—at a minimum—disease- and treatment-related symptoms and physical, social, and psychological functioning.12 Longitudinal QoL investigation is essential. A baseline QoL assessment establishes whether treatment groups differ in pretreatment QoL and, thus, can be compared to posttreatment QoL indices for each group. Quality-of-life assessment is also performed at the completion of treatment to study the acute adverse effects of therapy, and weeks to months later to evaluate late effects and how they affect the patient.

A review of English-language medical and nursing literature generated over the past decade reveals few prospective longitudinal investigations of QoL in esophageal cancer that used a validated multidimensional QoL instrument and/or an esophageal-specific assessment scale. Most of these investigations focused on palliative end points, such as relief of dysphagia, or were performed in the context of metastatic disease.13–15 Moreover, few prospective studies have examined longitudinal QoL in patients with esophageal cancer undergoing potentially curative treatment,16–25 and only four prospective assessments of QoL in patients receiving combined-modality therapy have been reported recently.22–25

Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 94–05 was an Intergroup phase III trial designed to investigate radiation dose escalation to 64.8 Gy with concurrent standard 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with esophageal cancer. The control group in this study received a modified version of the chemoradiotherapy (CRT) regimen from RTOG 85–01, using CD radiation to 50.4 Gy.26 Preliminary survival results demonstrated no significant difference in median survival or 2-year survival between the high-dose (HD) and conventional dose (CD) arms.27 This study included prospective QoL evaluation as a secondary end point using validated multidimensional constructs.

The purpose of this report is to document the longitudinal QoL outcome of patients with esophageal cancer receiving definitive CRT with CD RT to 50.4 Gy as compared with HD RT to 64.8 Gy using a validated cancer-specific QoL instrument: the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT), Head and Neck (version 2), as amended by 15 supplemental esophageal-specific items.28–30

METHODS

Patient Population

Member institutions of RTOG (94–05), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG R9405), and the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG 94–40–51) entered patients into this trial. RTOG served as the coordinating group and was responsible for data collection and analysis. The study opened in June 1995 with a goal to accrue 298 patients. The study was closed after an interim analysis reviewed by the Data Monitoring Committee in July 1999 revealed that the chance of the HD arm showing a significant survival advantage compared with the CD arm was ≤2.5%. A total of 236 patients were accrued.

Eligibility Criteria and Pretreatment Evaluation

Patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM clinical classification T1–4N0–1M0 primary squamous cell or adenocarcinoma of the cervical, mid-, or distal esophagus were eligible for enrollment.31 Other eligibility criteria have been previously reported and included Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) ≥60%, chest/abdominal computed tomography scan revealing no evidence of metastatic disease, and adequate nutritional intake.27 Eligibility was also limited to patients whose tumor did not extend to within 2 cm of the gastroesophageal junction. Patients with multiple tumors of the esophagus, metastatic disease, or prior esophageal chemotherapy, RT, or surgical resection were ineligible. Patients with cervical primaries with positive supraclavicular lymph nodes (defined as N1) were eligible; however, patients with noncervical primaries with positive supraclavicular lymph nodes (defined as M1) were ineligible. Pretreatment clinical evaluation has been previously reported.27 This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Treatment Protocols

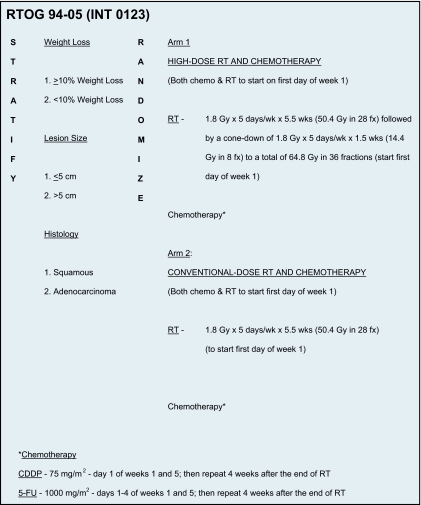

All patients received four cycles of 5-FU and cisplatin chemotherapy plus concurrent radiotherapy as shown in Figure 1. Radiotherapy began on day 1, with the beginning of cycle 1 of chemotherapy. Four weeks after the completion of RT, patients were to receive two additional cycles (days 1 and 29) of chemotherapy. Details of the RT protocol have been previously described.27 The initial target volume prescription dose was 50.4 Gy delivered in 28 1.8-Gy daily fractions Monday through Friday. The superior and inferior borders of the radiation field were 5 cm beyond the primary tumor. The lateral, anterior, and posterior borders of the field were ≥2 cm beyond the borders of the primary tumor. The primary tumor and regional lymph nodes were included. Patients assigned to the HD arm received a cone-down field of 14.4 Gy to the primary tumor, with a 2 cm margin to a total dose of 64.8 Gy delivered in 36 1.8-Gy daily fractions.

Figure 1.

Treatment schema for RTOG 94–05. Abbreviations: 5-FU = 5-fluorouracil; CDDP = cisplatin; Fx = fraction; Wk = week.

Patients were examined weekly throughout all phases of the treatment program and prior to each chemotherapy cycle to assess adverse events. The National Cancer Institute's Cooperative Group Common Toxicity Criteria were used to measure acute chemotherapy toxicity. Acute and late RT toxicity was scored according to the RTOG morbidity scoring criteria.

Quality of Life Assessment

This study included prospective QoL evaluation as a secondary end point. QoL assessments used the FACT Head & Neck (HN), version 2, as amended by 15 supplemental esophageal-specific questions.30 The FACT-HN measure had been chosen, as no validated QoL instrument specific for esophageal cancer existed at the time of this trial's inception. FACT-HN is a validated multidimensional self-report questionnaire that quantitatively assesses how the patient feels with respect to five subscales, as follows: physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being, as well as their relationship with the physician.28,29 The head and neck subscale has eight site-specific questions. RTOG added 15 additional questions adapted from the FACT lung and bladder modules (version 2) specifically for patients with esophageal cancer. These additional esophageal-specific items have not been previously validated.

QoL assessments were administered at baseline, at completion of CRT, and then at 8 months and at 1 year from the start of CRT.

Statistical Methods

This study was not prospectively powered for QoL end points because QoL participation was not mandated. To assess selection bias in participation, the chi-square test was used to compare pretreatment characteristics between participants and nonparticipants.

The responses to the FACT-HN questionnaire were scored using standard, previously described scoring methods.30 For scores related to total QoL and functioning domains, higher scores indicated better functioning. Multiple imputation methods for longitudinal data, as described by Fairclough, were used to impute missing QoL scores beyond baseline.32 Specifically, the multiple imputation procedure in SAS/STAT® software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) with the regression method was used. This method imputes missing values within a case using previously observed and imputed data. Imputations were performed separately within treatment arms, and significant baseline explanatory variables were used in the imputation process.

Change in QoL from baseline to each of the three subsequent assessment time points (completion of CRT and at 8 and 12 months from the start of CRT) was calculated for each treatment arm and compared using the t test for independent samples. Additionally, the total QoL scores were compared between the treatment arms at each assessment time point, using the t test for independent samples. Cox regression models were used to determine associations between QoL and efficacy (overall survival, locoregional failure, and distant failure).

Fifteen additional esophageal-specific items were addressed and tested at baseline and at all follow-up time points. Internal consistency (reliability) of the original FACT H&N (version 2) subscale with the new esophageal-specific questions was measured using Cronbach's alpha.33

Randomization

The randomization schema described by Zelen34 was used to achieve balance in the treatment assignments among the institutions, with three stratification variables: weight loss (<10% vs. ≥10%), tumor size (≤5 cm vs. >5 cm), and histologic cell type (adenocarcinoma vs. squamous). Patients were randomly assigned either to the 64.8 Gy or 50.4 Gy arms.

RESULTS

Pretreatment Characteristics

A total of 236 patients with clinical stage T1–4N0–1M0 squamous cell or adenocarcinoma of the esophagus were randomized to receive definitive CRT consisting of four monthly cycles of 5-FU and cisplatin with concurrent 50.4 Gy RT vs. the same chemotherapy schedule but with concurrent 64.8 Gy RT. Of the 218 eligible and analyzable patients, 52 patients did not participate in QoL assessment; the principal reason was due to institutional error (Table 1). Baseline QoL questionnaires were not accepted after the initiation of protocol therapy.

Table 1.

Reasons for nonparticipation in baseline QoL

| Reasons | 64.8 Gy (n) | 50.4 Gy (n) |

|---|---|---|

| QoL form incomplete | 6 | 4 |

| QoL after start of treatment | 6 | 4 |

| Patient refused | 3 | 1 |

| Institution error | 6 | 8 |

| Did not speak English | 2 | 1 |

| Other | 2 | 4 |

| Unknown | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 27 | 25 |

Abbreviation: QoL = quality of life.

Table 2 provides the distribution of pretreatment characteristics by participation in QoL. Patients with ≥10% loss of pretreatment total body weight (P = .02), and patients with lower pretreatment KPS (70%–80%, P = .002), were significantly less likely to participate in QoL analysis. Pretreatment characteristics of the 166 patients with baseline QoL assessments are shown in Table 3. The arms were well balanced for weight loss, gender, race, age, KPS, primary tumor size, histology, clinical T-stage, and clinical N-stage.

Table 2.

Pretreatment characteristics by QoL completion

| Pretreatment characteristic | QoL (n=166) | No QoL (n=52) | χ2 test P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 120 (72%) | 34 (65%) | .34 |

| Female | 46 (28%) | 18 (35%) | ||

| Race | White | 113 (68%) | 31 (60%) | White vs. non-white |

| Hispanic | 4 (2%) | 3 (8%) | .26 | |

| Black | 48 (29%) | 17 (33%) | ||

| Asian/Pacific | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| Weight loss | >10% | 62 (37%) | 29 (56%) | .02* |

| <10% | 104 (63%) | 23 (44%) | ||

| Age | Median | 64 | 63 | .16 |

| Range | 43–81 | 37–78 | ||

| KPS | 60–80 | 65 (39%) | 33 (63%) | .002* |

| 90–100 | 101 (61%) | 19 (37%) | ||

| Lesion size | <5 cm | 79 (48%) | 25 (48%) | .95 |

| >5 cm | 87 (52%) | 27 (52%) | ||

| Histology | Squamous | 138 (83%) | 47 (90%) | .20 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 28 (17%) | 5 (10%) | ||

P values significant at the.05 level.

Abbreviations: KPS = Karnofsky performance status; QoL = quality of life.

Table 3.

Pretreatment patient and tumor characteristics by treatment arm

| Pretreatment characteristic | 64.8 Gy (n=82) | 50.4 Gy (n=84) | χ2 test P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 56 (68%) | 64 (76%) | .26 |

| Female | 26 (32%) | 20 (24%) | ||

| Race | White | 60 (73%) | 53 (63%) | White vs. non-white |

| Hispanic | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | .16 | |

| Black | 20 (24%) | 28 (33%) | ||

| Asian/Pacific | 0 | 1 (1%) | ||

| Weight loss | >10% | 30 (37%) | 32 (38%) | .84 |

| <10% | 52 (63%) | 52 (62%) | ||

| Age | Median | 65 | 64 | .34 |

| Range | 44–80 | 43–81 | ||

| KPS | 60–80 | 30 (37%) | 35 (42%) | .50 |

| 90–100 | 52 (63%) | 49 (58%) | ||

| Lesion size | <5 cm | 38 (46%) | 41 (49%) | .75 |

| >5 cm | 44 (54%) | 43 (51%) | ||

| Histology | Squamous | 69 (84%) | 69 (82%) | .73 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 13 (16%) | 15 (18%) | ||

Abbreviation: KPS = Karnofsky performance status.

Quality of Life Compliance

QoL compliance rates were measured as a percentage of all eligible patients completing QoL forms. One hundred sixty-six patients completed QoL forms at baseline. Patterns of QoL compliance at treatment completion and at 8 and 12 months for these patients are shown in Table 4. The main reason for noncompliance was missing QoL assessment forms. The other documented reasons for noncompliance included institutional error (delinquent or incomplete data), patient refusal or patient illness, and patient not seen for scheduled follow-up. Thirty-four patients (20%) completed questionnaires at all four time points. Thirty-nine patients (23%) completed assessment forms at two of the three time points after baseline; 45 patients (27%) completed an assessment form at only one time point after baseline, and 51 patients (30%) only provided baseline information.

Table 4.

Pattern of QoL compliance

| Baseline | Treatment completion | 8 months | 12 months | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | X | X | X | 34 | 20 |

| X | X | X | 21 | 12 | |

| X | X | X | 11 | 7 | |

| X | X | X | 7 | 4 | |

| X | X | 30 | 18 | ||

| X | X | 11 | 7 | ||

| X | X | 4 | 2 | ||

| X | 51 | 30 |

Abbreviation: QoL = quality of life.

Radiation Dose and QoL

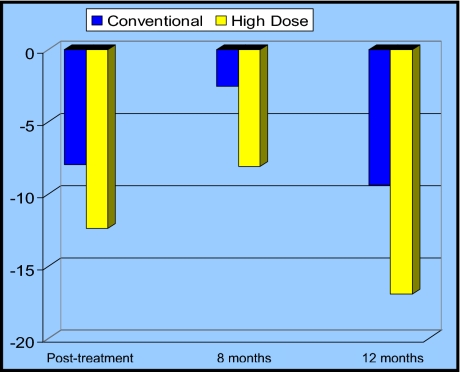

At the completion of CRT, the mean change from baseline in total QoL score was decreased in both arms (Figure 2, Table 5). Of note, this mean change was not significantly decreased in the HD arm as compared to the CD arm (P = .13). There was also no significant difference between the treatment arms with respect to mean change in total QoL from baseline to 8 months, or baseline to 12 months following the start of CRT (P = .17 and P = .24, respectively).

Figure 2.

Mean change in total quality of life (QoL) scores by treatment arm. The y-axis represents the mean change in total QoL scores from baseline. Conventional dose (CD) represents the 50.4 Gy arm; high dose (HD) represents the 64.8 Gy arm. At the completion of CRT (posttreatment) and at the two subsequent time points, the mean change in total QoL scores was not significantly different between the two treatment arms.

Table 5.

Mean change* in total QoL from baseline by treatment arm

| Time point | 64.8 Gy (n=82) | 50.4 Gy (n=84) |

|---|---|---|

| Posttreatment | ||

| Mean | −12.39 | −7.95 |

| SE | 2.9035 | 2.6372 |

| P value | .13 | |

| 8 months | ||

| Mean | −8.10 | −2.57 |

| SE | 4.1793 | 3.8742 |

| P value | .17 | |

| 12 months | ||

| Mean | −16.90 | −2.0 |

| SE | 9.5874 | 4.3149 |

| P value | .24 | |

A negative change indicates a decline in QoL.

Abbreviations: QoL = quality of life; SE = standard error.

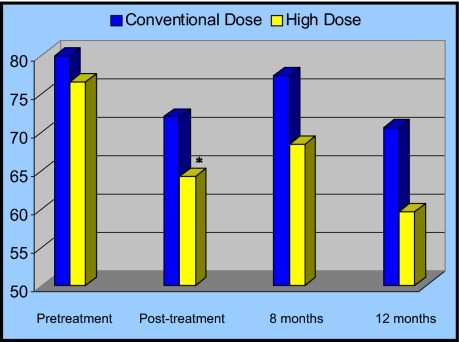

Figure 3 and Table 6 show mean total QoL scores by treatment arm at each assessment time point. Total QoL scores were similar in each arm prior to treatment. The HD arm had significantly lower total QoL at the end of CRT, as compared to the standard dose arm (P = .02), and a trend toward this same result was seen at 8 months from the start of CRT (P = .07). Total QoL was also lower for the HD arm at 12 months from the start of CRT, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = .16).

Figure 3.

Mean total quality of life (QoL) scores by treatment arm. The y-axis represents mean total QoL scores. Conventional dose (CD) represents the 50.4 Gy arm; high dose (HD) represents the 64.8 Gy arm. At the completion of CRT (posttreatment), total QoL was significantly worse in the HD arm as compared to the CD arm (*P = .02). These significant differences were resolved by 8 months following treatment. *P values significant at the .05 level.

Table 6.

Total QoL by treatment arm

| Time point | 64.8 Gy (n=82) | 50.4 Gy (n=84) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||

| Mean | 76.48 | 79.86 |

| SE | 2.9835 | 1.9886 |

| P value | .17 | |

| Posttreatment | ||

| Mean | 64.09 | 71.91 |

| SE | 2.8702 | 2.471336 |

| P value | .02 | |

| 8 months | ||

| Mean | 68.3828 | 77.30 |

| SE | 4.3376 | 4.0113 |

| P value | .07 | |

| 12 months | ||

| Mean | 59.58 | 70.49 |

| SE | 9.7298 | 4.6308 |

| P value | .16 | |

Abbreviations: QoL = quality of life; SE = standard error.

Intercorrelation Between FACT H&N and Additional Esophageal-Specific Questions

Fifteen additional esophageal-specific items were addressed (Table 7) and tested at baseline and at all follow-up time points. Internal consistency (reliability) of the original FACT H&N (version 2) subscale with the new esophageal-specific questions was an alpha of 0.66.

Table 7.

Fifteen additional esophageal-specific test questions

| Additional Concerns During the Past 7 Days: |

|---|

| I have been bothered by hair loss |

| I have been short of breath |

| I can swallow liquids |

| I have a good appetite |

| I have diarrhea |

| I am bothered by a change in weight |

| I am bothered by eating in public |

| I eat a wide variety of foods |

| I am able to eat by mouth |

| I have difficulty hearing |

| I am bothered by the way I feel when I eat |

| I have pain or discomfort related to my cancer |

| I have been coughing |

| A need to eat frequently bothers me |

| I tend to eat alone |

Answers are presented in a five-point Likert format with responses from 0 (not at all) to 4.

Conventional Outcomes and QoL

The median follow-up was 16.4 months (range 13.0–19.4 months). No significant difference was seen in median survival (12.9 months 95% confidence interval [CI], 10.5–19.3 months vs. 18.1 months 95% CI, 15.0–23.1 months) or 2-year survival (30% vs. 39%) between the HD and CD arms.27 This inferior survival rate was initially attributed to the increased number of treatment-related deaths in the HD arm: 11 deaths vs. 2 in the CD arm. Of these 11 treatment-related deaths, 7 occurred in patients who had received ≤50.4 Gy. A separate survival analysis including only patients who received their assigned dose of radiation, though biased, still revealed no survival advantage with the 64.8 Gy arm.27 Similarly, there were no significant differences in the rates of locoregional (51% vs. 55%) and distant failure (9% vs. 15%) in the HD vs. the CD arm.

In terms of QoL, scores on the physical, social, emotional, and functional FACT subscales and mean total QoL were not significantly associated with overall survival or local failure for either treatment arm.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, oncology has increasingly accepted that the goals of cancer therapy should incorporate concerns not only regarding efficacy of tumor control but also patients' QoL throughout the disease and management course. This study, to our knowledge, is the first prospective longitudinal QoL study evaluating randomized CRT strategies for localized esophageal cancer using validated QoL and symptom-specific instruments. Our findings show that total mean QoL declined after CRT, most significantly in the dose-escalated arm. Total mean QoL remained lower in the 64.8 Gy arm at 8 and 12 months after the start of CRT, but these values did not reach statistical significance when compared to the 50.4 Gy arm.

Prospective QoL changes have been reported after esophagectomy.16–21 Blazeby et al assessed long-term QoL in 92 consecutive patients with esophageal carcinoma undergoing potentially curative resection.19 The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) core QoL instrument (QLQ-C30) and the dysphagia scale from the EORTC esophageal-specific module (QLQ-OES24) were administered before treatment and at regular intervals until death or for 3 years. Six weeks after esophagectomy, patients reported worse QoL scores than before treatment. In patients who survived at least 2 years, QoL scores were restored to preoperative levels within approximately 9 months.

Only four other reports have been made of prospective QoL evaluations incorporating the recommended minimal core domains or treatment-specific tools for patients with esophageal cancer undergoing therapy with CRT with or without surgical resection.22–25 Blazeby et al investigated longitudinal QoL changes using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OES18 instruments in 103 consecutive patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgical resection.22 Patients reported deterioration in most aspects of QoL during preoperative treatment, which returned to baseline levels before surgical resection in those who did not have disease progression. Six weeks after esophagectomy, patients reported a significant decline in physical, role, and social function; these scores recovered to preoperative levels within 6 months. Two other smaller series reported similar findings.23,24

Longitudinal QoL was also assessed as part of a phase III trial (FFCD 9102) in patients receiving CRT with or without surgery for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.25 The Spitzer QoL index was administered at baseline and at subsequent follow-up for 2 years. The mean QoL score decreased following therapy in both treatment arms, more so in the surgery arm. However, longitudinal QoL was restored to baseline values in survivors by 2 years.

Similar to these other reports, our data show a recovery in mean total QoL scores at 8 months following definitive CRT. However, we again notice a decline in mean total QoL scores at 12 months posttreatment, most notably in the HD arm. Although total QoL scores did not correlate with local control or survival in our study, one could postulate that such scores may be associated with late effects, such as esophageal strictures, in patients who remain disease free. As such, we are in the process of collecting these data. It is also important to note that QoL compliance at 12 months was only 48%.

Missing data are a challenge that affects many QoL studies.35–37 This issue is of particular importance to randomized phase III trials concerning QoL end points. If patients who are experiencing treatment toxicity or progressive disease do not complete the questionnaires, analyses based only on data collected could lead to biased conclusions.36 In this study, as well as other RTOG studies, baseline QoL was not mandated as part of the pretreatment evaluation. RTOG believes that this allows patients who want to participate in a clinical trial, but who do not want to participate in the QOL portion, to still have access to the trial and its potential benefits. As such, the baseline rate of completion to this study was 81% of the total number of accrued patients, with nonwhite patients and those with higher pretreatment weight loss and lower pretreatment KPS significantly less likely to participate. We did take measures to minimize bias for missing data, because missing values were assigned using a multiple imputation method. As both weight loss and KPS were associated with QoL participation, these two variables, along with survival time, were used as covariates in the imputation regression model to determine our results.

Although this attrition in questionnaire completion is common to QoL research, QoL investigations must use strategies to enhance compliance and thereby minimize missing data. All QoL questionnaires should be monitored for completeness. Patients who are unable to come in for scheduled visits should be contacted for alternative follow-up. At RTOG annual meetings, lectures with investigators and roundtables with data managers are routinely performed to stress this important issue. Moreover, RTOG is evaluating novel methods, such as web-based patient-reported assessments, to ensure collection of QoL data in future trials.

At the time of RTOG 94–05 conception, a QoL esophageal-specific module was not yet developed to use in conjunction with the FACT-G for QoL assessment. Therefore, it was decided to employ the FACT-HN, version 2, which did contain important questions regarding dysphagia, and to add 15 additional esophageal-cancer–specific test questions (Table 7). The internal consistency of the original FACT-HN subscale with the new esophageal-specific items used in this randomized comparison had a Cronbach's alpha of only 0.66. As such, our esophageal-specific score findings should be interpreted with caution and were not reported in the results.

Similarly, another limitation in this study, in addition to missing data, was the potential lack of sensitivity of the FACT-HN tool. Perhaps a validated QoL instrument tailored to this patient population would have yielded more robust data. Since the completion of this trial, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy for Esophageal Cancer (FACT-E) questionnaire has been developed. The FACT-E self-reporting scale is composed of the validated FACT-G core with a FACT-E subscale (commonly referred to as the Esophageal Cancer Subscale or ECS), which includes 17 additional items specific for symptoms and problems related to esophageal cancer, such as eating, appetite, swallowing, pain, talking/communicating, mouth dryness, breathing difficulty, coughing, and weight loss.

The FACT-E 44-item questionnaire has recently undergone psychometric testing in adult patients with esophageal cancer38 showing good construct validity when compared with the EORTC QLQ-30 and its specific esophageal module. FACT-E scores correlated well with several important clinical factors and were found to be responsive to change in patients treated with esophagectomy alone and in those treated with CRT. In the subset of patients treated with neoadjuvant CRT, a significant improvement was reported in the ECS, the swallowing subscale (Swallowing Index Subscale Score), and the eating subscale (Eating Index Subscale Score) at 6–8 weeks following CRT.

It is clear that the current challenge in clinical oncology research is to incorporate patient-reported QoL end points using validated cancer-specific instruments into prospective randomized trials with clear hypotheses that can ultimately lead to clinically meaningful interventions. These investigations will be critical in identifying novel therapies that can enhance both the quantity and quality of our cancer patients' lives. As such, RTOG strives to incorporate QoL and/or patient-reported outcome hypotheses in all phase III treatment trials. In RTOG's current phase III esophageal cancer study—RTOG 0436 “A Phase-III Trial Evaluating the Addition of Cetuximab to Paclitaxel, Cisplatin, and Radiation for Patients With Esophageal Cancer Who Are Treated Without Surgery”—we are prospectively examining statistically powered QoL secondary end points to complement the traditional outcome end point of overall survival. Using the FACT-E instrument, we will determine if the addition of cetuximab to standard 50.4 Gy CRT for locally advanced esophageal cancer will significantly improve specific symptom subscales (the ECS score, the Swallowing Index Subscale Score, as well as the Eating Index Subscale Score) at 6–8 weeks following CRT completion.

In conclusion, our results show that longitudinal mean total QoL after definitive CRT for esophageal cancer was significantly worse posttreatment in patients treated with HD (64.8 Gy) radiotherapy compared to patients who received CD (50.4 Gy) radiotherapy, with mean total QoL scores continuing to be poorer at 8 and 12 months after the initiation of CRT in the HD arm. Therefore, for patients treated with definitive CRT for esophageal cancer, radiation dose escalation to 64.8 Gy does not improve survival or patient reported QoL. These results lend further weight to our previous conclusion that radiotherapy to 50.4 Gy should remain the standard of care in patients treated with definitive CRT for esophageal cancer.

Footnotes

Supported by RTOG U10 CA21661, CCOP U10 CA37422, and Stat U10 CA32115 grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). This manuscript's contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI.

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or guardians who participated in this study.

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Iyer R, Wilkinson N, Demmy T, et al. : Controversies in the multimodality management of locally advanced esophageal cancer: evidence-based review of surgery alone and combined-modality therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 11:665–673, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coia LR, Minsky BD, John MJ, et al. : Patterns of care study design tree and management guidelines for esophageal cancer. American College of Radiology. Radiat Med 16:321–327, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reed CE: Surgical management of esophageal carcinoma. Oncologist 4:95–105, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cooper JS, Guo MD, Herskovic A, et al. : Chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced esophageal cancer: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomized trial (RTOG 85–01). Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Jama 281:1623–1627, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walsh TN, Noonan N, Hollywood D, et al. : A comparison of multimodality therapy and surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 335:462–467, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bosset JF, Gignoux M, Triboulet JP, et al. : Chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone in squamous-cell carcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 337:161–167, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Urba SG, Orringer MB, Turrisi A, et al. : Randomized trial of preoperative chemoradiation versus surgery alone in patients with locoregional esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 19:305–313, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stahl M, Stuschke M, Lehmann N, et al. : Chemoradiation with and without surgery in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol 23:2310–2317, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tepper JE, Krasna M, Niedzwiecki D, et al. : Phase III trial of trimodality therapy with cisplatin, fluorouracil, radiotherapy, and surgery compared with surgery alone for esophageal cancer: CALGB 9781. J Clin Oncol 26:1086–1092, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aaronson NK, Meyerowitz BE, Bard M, et al. : Quality of life research in oncology: past achievements and future priorities. Cancer 67:839–843, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moinpour CM, Feigl P, Metch B, et al. : Quality of life endpoints in cancer clinical trials: review and recommendations. J Natl Cancer Inst 81:485–495, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aaronson NK: Methodological issues in assessing the quality of life of cancer patients. Cancer 67:844–850, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ilson DH, Saltz L, Enzinger P, et al. : Phase II trial of weekly irinotecan plus cisplatin in advanced esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol 17:3270–3275, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ross P, Nicolson D, Cunningham J, et al. : Prospective randomized trial comparing mitomycin, cisplatin and protracted venous-infusion fluorouracil (PVI 5-FU) with epirubicin, cisplatin, and PVI 5-FU in advanced esophagogastric cancer. J Clin Oncol 20:1996–2004, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Conroy T, Etienne PL, Adenis A, et al. : Vinorelbine and cisplatin in metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus: response, toxicity, quality of life and survival. Ann Oncol 13:721–729, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brooks J, Kesler KA, Johnson CS, et al. : Prospective Analysis of quality of life after surgical resection for esophageal cancer: preliminary results. J Surg Oncol 81:185–194, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knippenberg FCE, Out JJ, Tilanus HW, et al. : Quality of life in patients with resected oesophageal cancer. Soc Sci Med 35:139–145, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. O'Hanlon DM, Harkin M, Karat D, et al. : Quality-of-life assessment in patients undergoing treatment for oesophageal carcinoma. Br J Surg 82:1682–1685, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blazeby JM, Farndon JR, Donovan J, et al. : A prospective longitudinal study examining the quality of life of patients with esophageal carcinoma. Cancer 88:1781–1787, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gradauskas P, Rubikas R, Saferis V: Changes in quality of life after esophageal resections for carcinoma. Medicina 42:187–194, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Boer AGEM, van Lanschot JJB, van Sandick JW, et al. : Quality of life after transhiatal compared with extended transthoracic resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol 20:4202–4208, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blazeby JM, Sanford E, Falk SJ, et al. : Health-related quality of life during neoadjuvant treatment and surgery for localized esophageal cancer. Cancer 103:1791–1799, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gillham CM, Aherne N, Rowley S, et al. : Quality of life and survival in patients treated with radical chemoradiation alone for oesophageal cancer. Clin Oncol 20:227–233, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Safieddine N, Xu W, Quadri SM, et al. : Health-related quality of life in esophageal cancer: effect of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgical resection. J Thorac and Cardiovasc Surg 137:36–42, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bonnetain F, Bouche O, Michel P, et al. : A comparative longitudinal quality of life study using the Spitzer quality of life index in a randomized multicenter phase III trial (FFCD 9102): chemoradiation followed by surgery compared with chemoradiation alone in locally advanced squamous resectable thoracic esophageal cancer. Ann Oncol 17:827–834, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Herskovic A, Martz LK, Al-Sarraf M, et al. : Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 326:1593–1598, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Minsky BD, Pajak TF, Ginsberg RJ, et al. : INT 0123 (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 94–05) Phase III Trial of Combined Modality Therapy for Esophageal Cancer: High-Dose Versus Standard-Dose Radiation Therapy. J Clin Oncol 20:1167–1174, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. List MA, D'Antonio LL, Cella DF, et al. : The Performance Status Scale for head and neck cancer patients and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Head and Neck (FACT-H&N) scale: a study of utility and validity. Cancer 77:2294–2301, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. D'Antonio LL, Zimmerman GJ, Cella DF, et al. : Quality of life and functional status measures in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122:482–487, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cella DF: Manual for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) Scales version 2, April 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 31. American Joint Committee on Cancer: Esophagus, in Beahrs OH, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, et al. (eds): Handbook for Staging of Cancer (4th ed). Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott, pp 75–79, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fairclough DL: Design and Analysis of Quality of Life Studies in Clinical Trials New York, Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cronbach LJ: Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16:297–334, 1951 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zelen M: The randomization and stratification of patients to clinical trials. J Chronic Dis 27:365–375, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Curran D, Molenberghs G, Fayers P, et al. : Aspects of incomplete quality of life in randomised trials: II Missing form. Stat in Med 17:697–709, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fayers P, Curran D, Machin D: Incomplete quality of life data in randomized trials: missing items. Stat in Med 17:679–696, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. IGEO: The Italian Group for the Evaluation of Outcomes in Oncology (IGEO): patient compliance with quality of life questionnaires. Tumori 85:92–99, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Darling G, Eton DT, Sulmann J, et al. : Validation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Esophageal Cancer Subscale (FACT-E). Cancer 107:854–863, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]