Abstract

Summary

Background and objectives:

The association between pretransplant body composition and posttransplant outcomes in renal transplant recipients is unclear. It was hypothesized that in hemodialysis patients higher muscle mass (represented by higher pretransplant serum creatinine level) and larger body size (represented by higher pretransplant body mass index [BMI]) are associated with better posttransplant outcomes.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements:

Linking 5-year patient data of a large dialysis organization (DaVita) to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, 10,090 hemodialysis patients were identified who underwent kidney transplantation from July 2001 to June 2007. Cox regression hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of death and/or graft failure were estimated.

Results:

Patients were 49 ± 13 years old and included 49% women, 45% diabetics, and 27% African Americans. In Cox models adjusted for case-mix, nutrition-inflammation complex, and transplant-related covariates, the 3-month-averaged postdialysis weight-based pretransplant BMI of 20 to <22 and < 20 kg/m2, compared with 22 to <25 kg/m2, showed a nonsignificant trend toward higher combined posttransplant mortality or graft failure, and even weaker associations existed for BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. Compared with pretransplant 3-month- averaged serum creatinine of 8 to <10 mg/dl, there was 2.2-fold higher risk of combined death or graft failure with serum creatinine <4 mg/dl, whereas creatinine ≥14 mg/dl exhibited 22% better graft and patient survival.

Conclusions:

Pretransplant obesity does not appear to be associated with poor posttransplant outcomes. Larger pretransplant muscle mass, reflected by higher pretransplant serum creatinine level, is associated with greater posttransplant graft and patient survival.

Introduction

An obesity paradox has been consistently observed in dialysis patients, but conflicting data have been published about the association of pretransplant body size and weight with posttransplant graft and patient survival in renal transplant recipients. Early studies had reported poorer kidney transplant outcomes in obese dialysis patients (1–4), mainly because of cardiovascular (5) and infectious complications such as surgical wound infections (6). However, more recent studies have reported that weight change before transplantation did not correlate with graft loss and death after kidney transplantation (7), although obese recipients develop diabetes mellitus or surgical complications more frequently (6,8–11). Many transplant centers exclude or suspend obese patients with a body mass index (BMI) >30 or >35 kg/m2 from the transplant waitlist and refer them for weight reduction strategies such as bariatric surgery (12). However, clinical trials of bariatric surgery in populations without kidney disease indicate comparable weight loss but higher postsurgery mortality (13). In a recent report, BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 was the third most common reason to deny transplant waitlisting and affecting 10% of potential renal transplant candidates (14). Because the long-term consequences of obesity after transplantation remain unclear (5,15), it is important to address the potential association between pretransplant body composition and posttransplant outcomes.

Previous studies of obesity in kidney transplant recipients used solely BMI to define obesity (1–4), but BMI is unable to differentiate between adiposity and muscle mass (16). Reduced muscle mass (sarcopenia) is a predictor of mortality in dialysis patients (17). To better characterize patients' nutritional status, additional parameters such as waist circumference or serum creatinine have been suggested (17–22). Indeed, in maintenance dialysis patients with minimal residual function under steady state, serum creatinine may better reflect muscle mass compared with BMI (17,19–22). However, the association of pretransplant serum creatinine in dialysis patients with various posttransplant outcomes has not been studied in kidney transplant recipients. We hypothesized that higher pretransplant BMI and larger muscle mass as represented by higher pretransplant serum creatinine concentration during the weeks immediately before the kidney transplantation are associated with better posttransplant patient and graft survival.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We linked the list of renal transplant recipients under the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) up to June 2007 to the list of maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients who received treatment from July 2001 to June 2006 in any outpatient dialysis clinic of a U.S.-based large dialysis organization (DaVita, Inc, before its acquisition of former Gambro dialysis facilities). The institutional review committees of Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–University of California–Los Angeles and DaVita Clinical Research approved the study.

Clinical and Demographic Measures

The creation of the national DaVita MHD patient cohort has been described previously (22–26). To minimize measurement variability, all repeated measures for each patient during the last calendar quarter before kidney transplantation (i.e., over a 13-week or 3-month interval) were averaged and the quarterly means were used. In addition to quarterly laboratory values, posthemodialysis weight (to calculate 3-month averaged BMI) was also recorded using up to 39 recoded posthemodialysis weight measurements from the thrice-weekly MHD treatment.

We divided pretransplant BMI into six a priori selected categories: <20, 20 to <22, 22 to <25, 25 to <30, 30 to <35, and ≥35 kg/m2. These increments were most consistent with our previous study (27). The pretransplant serum creatinine levels, usually measured at least once monthly immediately before a mid-week hemodialysis treatment, were divided into seven a priori selected categories: <4, 4 to <6, 6 to <8, 8 to <10, 10 to <12, 12 to <14, and ≥14 mg/dl. Dialysis vintage was defined as the duration of time between the first day of dialysis treatment and the day of kidney transplantation.

Laboratory Measures

Blood samples were drawn using uniform techniques in all of the DaVita dialysis clinics and were transported to the DaVita Laboratory in Deland, Florida, typically within 24 hours. All laboratory values were measured by automated and standardized methods in the DaVita Laboratory. Most laboratory values were measured monthly, including serum creatinine, urea, albumin, calcium, phosphorus, bicarbonate, and total iron binding capacity. Serum ferritin and intact PTH were measured at least quarterly. Hemoglobin was measured weekly to biweekly in most patients. Most blood samples were collected predialysis, with the exception of the postdialysis serum urea nitrogen to calculate urea kinetics. Kt/V (single pool) was calculated using urea kinetic modeling equations as described elsewhere (25). Albumin-corrected calcium was calculated by subtracting 0.8 mg/dl for each 1 g/dl of serum albumin below 4.0 g/dl (28).

Statistical Analyses

Survival analyses included Cox proportional hazards regression models using variables recorded during the last pretransplant calendar quarter. Graft failure was defined as initiation of dialysis treatment or retransplantation. For each analysis, three models were examined based on the level of multivariate adjustment:

A minimally adjusted (referred to as “unadjusted”) model that included mortality data and entry calendar quarter (q1 through q20)

Case-mix adjusted models that included all of the above plus age, sex, race, and ethnicity (African Americans and other self-categorized blacks, non-Hispanic whites, Asians, Hispanics, and others), diabetes mellitus, dialysis vintage (<6 months, 6 months to 2 years, 2 to 5 years and ≥5 years), primary insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, private, and others), marital status (married, single, divorced, widowed, and other or unknown), the standardized mortality ratio of the dialysis clinic during entry quarter, dialysis dose as indicated by Kt/V (single pool), presence or absence of a dialysis catheter, and residual renal function during the entry quarter (i.e., urinary urea clearance)

Case-mix malnutrition-inflammation-complex syndrome (MICS) and transplant-data-adjusted models that included all of the covariates in the case-mix model and ten surrogates of nutritional status and inflammation, including 11 laboratory variables with known association with clinical outcomes in MHD patients (i.e., normalized protein catabolic rate as an indicator of daily protein intake [also known as the normalized protein nitrogen appearance (29)] and serum or blood concentrations of albumin, total iron binding capacity, ferritin, phosphorus, calcium, bicarbonate, peripheral white blood cell count, lymphocyte percentage, and hemoglobin) plus five transplant-related data (i.e., donor type [deceased or living], donor age, panel reactive antibody titer [last value before transplant], number of HLA mismatches, and cold ischemic time).

Sensitivity analyses were performed using time-averaged (time before transplant up to 5 years) and baseline data. Sporadically missing covariate data were imputed by the last value carried forward method. Proportional hazard assumption was tested using log(−log) against survival plots. Analyses were carried out with SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The original 5-year (July 2001 through June 2006) national database of all DaVita patients included 164,789 adult subjects. This database was linked via unique identification number to the national SRTR registry that included all transplant waitlisted people and renal transplant recipients up to June 2007 (see Figure e1 in Appendix). Of 37,766 DaVita MHD patients who were identified in the said SRTR database, 17,629 had undergone one or more kidney transplantations during their lifetime, but only 14,508 MHD patients had undergone their first renal transplantation between July 2001 and July 2007. After excluding those without electronically recorded posthemodialysis weight data (n = 1993), outlier BMI (<12 or >60 kg/m2) probably due to wrong height values (n = 768), subjects who interrupted MHD treatment before transplantation (n = 838), and those with outlier age (n = 57), 10,090 MHD patients remain in the study population. These patients were followed until death, graft failure, loss of follow-up, or survival until June 30, 2007, as recorded in the SRTR database. Among the 10,090 observed renal transplant recipients, there were 727 deaths (7.2%), including 150 patients who died after graft failure, and 759 graft failures (7.5%) irrespective of subsequent deaths. The median follow-up time was 832 days, with a maximum of 2185 days.

Table 1 compares the demographic, clinical, and pretransplant laboratory characteristics of the 10,090 transplanted and 128,668 nontransplanted MHD patients in the 5-year DaVita cohort. Both groups had the same mean BMI; however, transplanted patients were 14 years younger and less likely to be diabetic, African American, or to have Medicare as their primary insurance. With the exception of serum bicarbonate and blood white blood cell count, transplanted patients had significantly different laboratory values, mostly indicative of better nutritional status.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics for 138,758 long-term HD patients

| Variables | Transplanted | Not Transplanted | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10,090 | 128,668 | <0.01 |

| Age (years) | 49 ± 13 | 63 ± 15 | <0.01 |

| Gender (% women) | 49 | 50 | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 45 | 50 | <0.01 |

| Racial/ethnicity minorities | |||

| African Americans | 27 | 32 | <0.01 |

| Hispanics | 15 | 14 | <0.01 |

| Asians | 4 | 3 | <0.01 |

| Vintage (time on dialysis) (%) | <0.01 | ||

| <6 months | 12 | 18 | <0.01 |

| 6 to 24 months | 29 | 30 | 0.02 |

| 2 to 5 years | 37 | 32 | <0.01 |

| >5 years | 23 | 21 | <0.01 |

| Primary insurance (%) | <0.01 | ||

| Medicare | 51 | 63 | <0.01 |

| Medicaid | 3 | 5 | <0.01 |

| private insurance | 18 | 8 | <0.01 |

| other | 19 | 15 | <0.01 |

| Marital status (%) | <0.01 | ||

| married | 47 | 40 | <0.01 |

| divorced | 6 | 7 | <0.01 |

| single | 26 | 23 | <0.01 |

| widowed | 3 | 14 | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 ± 5.6 | 26.7 ± 6.6 | 0.87 |

| Kt/V (dialysis dose) | 1.62 ± 0.35 | 1.53 ± 0.36 | <0.01 |

| Protein catabolic rate (g/kg/day) | 1.05 ± 0.26 | 0.94 ± 0.26 | <0.01 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 4.03 ± 0.38 | 3.64 ± 0.48 | <0.01 |

| creatinine (mg/dl) | 10.6 ± 3.2 | 7.7 ± 3.2 | <0.01 |

| bicarbonate (mg/dl) | 21.9 ± 3.4 | 22.4 ± 3.1 | <0.01 |

| TIBC (mg/dl) | 212 ± 40 | 207 ± 47 | <0.01 |

| TSAT | 32.57 ± 12.63 | 26.41 ± 11.86 | <0.01 |

| ferritin (ng/ml) | 530 ± 378 | 520 ± 502 | 0.02 |

| phosphorus (mg/dl) | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | <0.01 |

| calcium (mg/dl) | 9.4 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 0.7 | <0.01 |

| intact PTH (pg/ml) | 400 ± 415 | 341 ± 360 | <0.01 |

| alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 114 ± 80 | 122 ± 93 | <0.01 |

| Blood hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.3 ± 1.2 | 12.0 ± 1.4 | <0.01 |

| WBC (×103/μl) | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 7.5 ± 2.7 | <0.01 |

| lymphocyte (% of total WBC) | 23 ± 8 | 20 ± 8 | <0.01 |

| Number of HLA mismatch | 3.6 ± 1.8 | NA | NA |

| HLA A mismatch | 1.2 ± 0.8 | NA | NA |

| HLA B mismatch | 1.3 ± 0.8 | NA | NA |

| HLA DR/DW mismatch | 1.1 ± 0.7 | NA | NA |

| PRA (%) | 10.3 ± 24.0 | NA | NA |

| Cold ischemia time (hours) | 14.3 ± 10.6 | NA | NA |

| Donor type (% living) | 32 | NA | NA |

| Donor age (years) | 39 ± 15 | NA | NA |

Data for 10,090 patients who received transplants are from the quarter transplanted, or last quarter before transplant when data was available. Data for the remaining 128,668 DaVita patients who did not receive a transplant are from the base calendar quarter. Values are in percentage or mean ± SD, as appropriate. TIBC, total iron binding capacity; TSAT, transferrin saturation; PRA, panel reactive antibody (last value before transplant); PTH, parathyroid hormone; WBC, white blood cell count; NA, not applicable.

As shown in Table 2, 83% of the transplanted patients were in the normal, overweight, or mildly obese BMI categories (i.e., BMI in the 20- to 35-kg/m2 range). Crude mortality was the lowest in the highest BMI category (>35 kg/m2). However, the highest (>35 kg/m2) and the lowest BMI groups (<20 kg/m2) exhibited slightly more graft failures (9%) compared with the other BMI groups (7% to 8%) over the 6 years of observation. As shown in Table 3 the highest serum creatinine category (>14 mg/dl), reflecting the largest muscle mass, was associated with the lowest crude mortality (4%), whereas the lowest serum creatinine category (<4 mg/dl) was associated with the highest crude graft failure rate (13%).

Table 2.

Incremental categories of BMI in MHD patients who subsequently underwent renal transplantation, including selected clinical and laboratory values in each group

| BMI Range (kg/m2) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20.0 | 20 to <22 | 22 to <25 | 25 to <30 | 30 to <35 | ≥35 | P for Trend | P ANOVA | |

| n (%) | 886 (9) | 1975 (12) | 2276 (23) | 3246 (32) | 1687 (17) | 820 (8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 43 ± 15 | 46 ± 14 | 50 ± 14 | 51 ± 13 | 50 ± 12 | 49 ± 12 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Deaths (and crude death rate) | 68 (8) | 89 (8) | 149 (7) | 241 (7) | 127 (8) | 53 (6) | 0.81 | 0.76 |

| Graft failure (%) | 76 (9) | 96 (8) | 160 (7) | 232 (7) | 122 (7) | 73 (9) | 0.61 | 0.16 |

| Gender (% women) | 59 | 42 | 34 | 33 | 36 | 44 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Race (black) | 22 | 22 | 25 | 26 | 32 | 36 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 13 | 19 | 23 | 31 | 33 | 39 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.5 ± 1.3 | 21.1 ± 0.6 | 23.5 ± 0.9 | 27.3 ± 1.4 | 32.2 ± 1.4 | 38.8 ± 3.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 52.1 ± 7.7 | 60.7 ± 7.78 | 68.8 ± 9.1 | 80.0 ± 10.8 | 93.7 ± 12.6 | 108.9 ± 17.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 9.9 ± 3.0 | 10.4 ± 3.1 | 10.7 ± 3.2 | 10.7 ± 3.2 | 10.8 ± 3.2 | 10.8 ± 3.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| men | 11.0 ± 3.2 | 11.2 ± 3.2 | 11.3 ± 3.3 | 11.3 ± 3.3 | 11.3 ± 3.3 | 11.2 ± 3.4 | 0.39 | 0.81 |

| women | 9.1 ± 2.7 | 9.4 ± 2.6 | 9.4 ± 2.7 | 9.5 ± 2.7 | 9.9 ± 2.9 | 10.2 ± 2.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 4.02 ± 0.42 | 4.05 ± 0.40 | 4.05 ± 0.40 | 4.03 ± 0.35 | 4.01 ± 0.34 | 3.94 ± 0.36 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| WBC (×103/μl) | 6.5 ± 2.1 | 6.7 ± 2.2 | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 6.9 ± 2.0 | 7.1 ± 2.0 | 7.4 ± 2.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Number of HLA mismatches | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 3.4 ± 1.9 | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 0.17 | 0.03 |

| PRA (%) | 15.2 ± 28.9 | 11.9 ± 26.0 | 9.3 ± 22.9 | 9.4 ± 22.8 | 9.5 ± 22.7 | 8.0 ± 21.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Donor age (years) | 37 ± 16 | 38 ± 15 | 39 ± 16 | 40 ± 15 | 40 ± 14 | 39 ± 14 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| Donor type (% living) | 36 | 33 | 30 | 32 | 30 | 30 | 0.006 | 0.02 |

| Cold ischemia time (hours) | 13.4 ± 10.2 | 13.9 ± 10.5 | 14.2 ± 10.4 | 14.5 ± 10.8 | 14.4 ± 10.4 | 14.9 ± 11.3 | 0.002 | 0.05 |

Values in parentheses represent the percent of the HD patients in each BMI category or the crude death rate or crude graft failure rate in the indicated group during the 6 years of observation, as appropriate. PRA is last value before transplant.

Table 3.

Incremental categories of 3-month-averaged serum creatinine concentration in MHD patients who subsequently underwent renal transplantation, including selected clinical and laboratory values in each group

| Serum Creatinine Range (mg/dl) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <4 | 4 to <6 | 6 to < | 8 to <10 | 10 to <12 | 12 to <14 | ≥14 | P for Trend | P ANOVA | |

| n (%) | 99 (1) | 489 (6) | 1249 (14) | 2000 (23) | 2123 (24) | 1547 (18) | 1314 (15) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 52 ± 14 | 54 ± 13 | 53 ± 12 | 52 ± 13 | 48 ± 13 | 44 ± 13 | 39 ± 12 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Deaths | 8 (8) | 56 (11) | 120 (10) | 200 (10) | 171 (8) | 92 (6) | 57 (4) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Failure | 13 (13) | 30 (6) | 100 (8) | 157 (8) | 157 (7) | 157 (10) | 160 (12) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Gender (% women) | 57 | 53 | 52 | 44 | 41 | 28 | 13 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Race (black) | 5 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 28 | 35 | 50 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 45 | 45 | 40 | 35 | 25 | 16 | 9 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 72.7 ± 18.5 | 73.0 ± 23.7 | 74.6 ± 18.8 | 76.3 ± 18.3 | 76.6 ± 18.6 | 78.6 ± 19.1 | 81.7 ± 17.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.0 ± 5.5 | 25.9 ± 8.3 | 26.4 ± 6.0 | 26.5 ± 5.5 | 26.5 ± 5.4 | 26.7 ± 5.5 | 27.2 ± 5.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| men | 26.3 ± 4.7 | 26.8 ± 5.0 | 26.8 ± 5.8 | 26.8 ± 5.1 | 26.7 ± 5.0 | 26.6 ± 5.2 | 27.0 ± 5.6 | 0.61 | 0.69 |

| women | 25.9 ± 6.0 | 25.1 ± 10.2 | 26.0 ± 6.2 | 26.2 ± 5.9 | 26.2 ± 5.9 | 26.9 ± 6.2 | 28.3 ± 6.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | |||||||||

| men | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 11.0 ± 0.6 | 12.9 ± 0.6 | 15.9 ± 1.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| women | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 10.9 ± 0.6 | 12.8 ± 0.6 | 15.4 ± 1.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.75 ± 0.57 | 3.82 ± 0.48 | 3.88 ± 0.42 | 3.98 ± 0.38 | 4.05 ± 0.33 | 4.10 ± 0.30 | 4.18 ± 0.30 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| WBC (×103/μl) | 7.4 ± 2.9 | 7.1 ± 2.6 | 6.9 ± 2.1 | 6.9 ± 2.1 | 6.8 ± 2.0 | 6.7 ± 1.9 | 6.6 ± 1.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Number of HLA mismatches | 3.1 ± 2.0 | 3.2 ± 1.9 | 3.4 ± 1.9 | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 3.5 ± 1.9 | 3.6 ± 1.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PRA (%) | 9.3 ± 23.3 | 9.8 ± 23.7 | 9.1 ± 22.6 | 8.0 ± 21.1 | 10.3 ± 24.1 | 11.3 ± 25.6 | 11.0 ± 25.0 | 0.21 | 0.01 |

| Donor age (years) | 42 ± 15 | 41 ± 14 | 41 ± 15 | 40 ± 15 | 38 ± 16 | 38 ± 15 | 37 ± 14 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Donor type (% living) | 49 | 49 | 40 | 33 | 28 | 26 | 27 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Cold ischemia time (hours) | 11.7 ± 12.1 | 11.7 ± 10.8 | 13.1 ± 11.0 | 14.1 ± 10.7 | 15.2 ± 10.4 | 15.2 ± 10.3 | 15.1 ± 10.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Values in parentheses represent the percent of the HD patients in each BMI category or the crude death rate or crude graft failure rate in the indicated group during the 6 years of observation, as appropriate. PRA is last value before transplant.

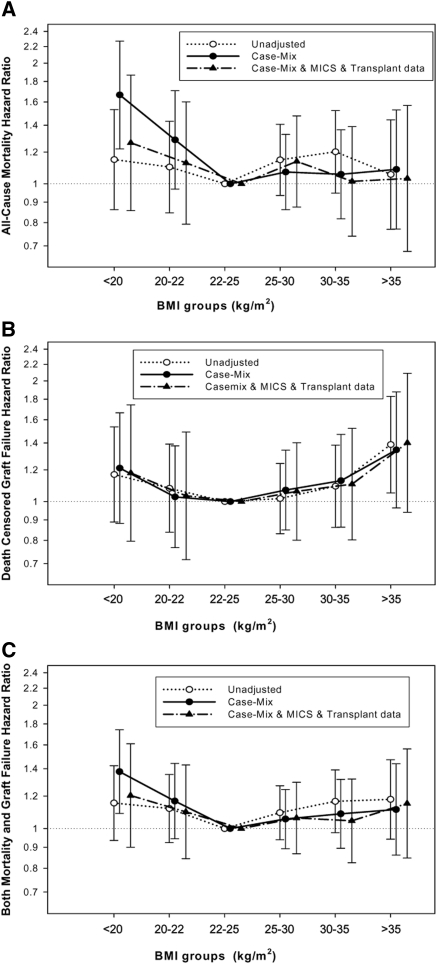

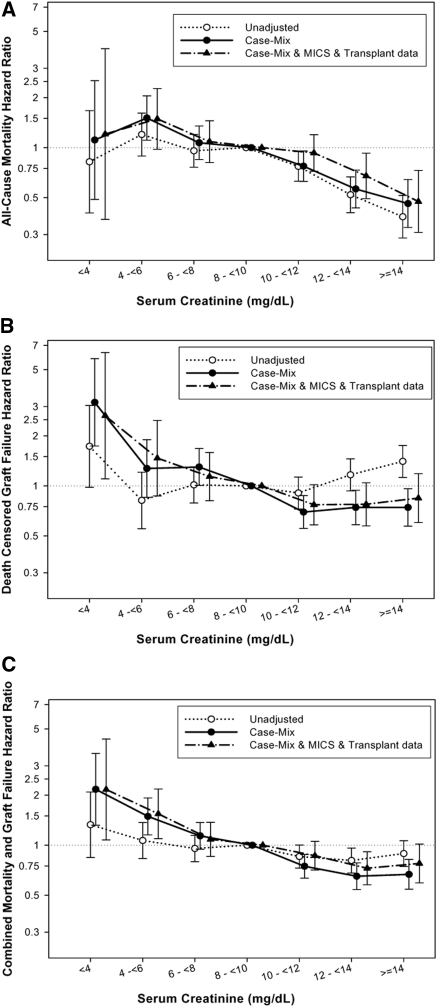

The associations of pretransplant 3-month-averaged serum creatinine and BMI categories with the posttransplant risk of death, graft failure, or the composite of graft failure or death are shown in Figures 1 and 2 and Table 4 (as well as Tables e1 through e6 in the Appendix). Using the group with pretransplant BMI in the 22- to <25-kg/m2 range as the reference, the case-mix-adjusted 6-year death risk in renal transplant recipients with a low BMI (<20 kg/m2) was 67% higher (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.67 [1.22 to 2.27], P = 0.001) (Figure 1A), although after additional adjustment for MICS and transplant-related variables this association mitigated. High pretransplant BMI (≥35 kg/m2) was associated with graft failure in the unadjusted model, but the association did not persist after multivariate adjustment (Figure 1B). Similar trends were observed with the composite of graft failure and death (Figure 1C). Sensitivity analyses after adjusting for ten pre-existing comorbid states including eight cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer resulted in similar findings (data not shown).

Figure 1.

HRs (95% confidence intervals) of (A) posttransplant-graft-censored death, (B) death-censored graft failure, and (C) combined mortality and graft failure across the pretransplant BMI categories using Cox regression analyses in 10,090 long-term MHD transplant patients who underwent renal transplantation and were observed over a 6-year observation period (July 2001 to June 2007).

Figure 2.

HRs (and 95% confidence intervals) of (A) posttransplant-graft-censored death, (B) death-censored graft failure, and (C) combined mortality and graft failure across pretransplant serum creatinine categories using Cox regression analyses in 10,090 MHD patients who underwent renal transplantation and were observed over a 6-year observation period (July 2001 to June 2007).

Table 4.

HR and 95% confidence intervals of posttransplant outcomes according to pretransplant 3-month-averaged BMI and serum creatinine values, using one single Cox regression model that includes both predictors, in 10,090 long-term MHD patients who underwent renal transplantation and were observed for up to 6 years after transplantation July 2001 to June 2007

| Minimally Adjusted |

Case-Mix Adjusteda |

Case-Mix, MICS, and Transplant-Data Adjustedb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Patients included in the model (n) | 8429 | 8357 | 5670 | ||||

| Number of events in models (n) | 640 | 637 | 443 | ||||

| Graft failure censored death | BMI | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.07 | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) | 0.95 | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.91 |

| Creatinine | 0.90 (0.87 to 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.87 to 0.93) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.95) | <0.001 | |

| Number of events in models (n) | 590 | 584 | 404 | ||||

| Death-censored graft failure | BMI | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.20 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.05 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.34 |

| Creatinine | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.06) | 0.01 | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.81 to 1.00) | 0.061 | |

| Number of events in models (n) | 1105 | 1097 | 762 | ||||

| Combined mortality and graft failure | BMI | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.12 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.48 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.79 |

| Creatinine | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.94) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97) | <0.001 | |

Calculated HRs are based on each 1-kg/m2 higher BMI or each 1-mg/dl higher serum creatinine concentration. CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, diabetes mellitus, dialysis vintage, primary insurance, marital status, the standardized mortality ratio of the dialysis clinic during entry quarter, dialysis dose as indicated by Kt/V (single pool), presence or absence of a dialysis catheter, and residual renal function during the entry quarter (i.e., urinary urea clearance).

Adjusted for all of the covariates in the case-mix model and normalized protein catabolic rate, serum or blood concentrations of albumin, total iron binding capacity, ferritin, phosphorus, calcium, bicarbonate, peripheral white blood cell count, lymphocyte percentage, and hemoglobin and five transplant-related data (i.e., donor type [deceased or living], donor age, panel reactive antibody titer [last value before transplant], number of HLA mismatches, and cold ischemic time).

Compared with patients with pretransplant 3-month-averaged serum creatinine of 8 to <10 mg/dl (reference), the patient groups with higher pretransplant serum creatinine (12 to <14 and ≥14 mg/dl) had 44% (HR: 0.56 [0.43 to 0.73]) and 54% (HR: 0.46 [0.33 to 0.64]) lower case-mix-adjusted death risk, respectively (P < 0.001). Importantly, patients with serum creatinine of 4 to <6 mg/dl had a 51% higher (HR: 1.51 [1.11 to 2.05], P = 0.01) case-mix-adjusted death risk (Figure 2A). These differences maintained even after adjustment for MICS and transplant data (Figure 2A). The lowest pretransplant creatinine groups had 2.6 times higher (HR: 2.64 [1.10 to 6.34]) graft failure risk (P = 0.03) (Figure 2B). Dialysis vintage was the confounder that contributed the most to the difference observed between unadjusted and multivariate-adjusted associations. Similar associations were also found for the composite outcome (Figure 2C). In particular, compared with the reference serum creatinine group (8 to <10 mg/dl), there was a 2.2-fold increased risk of combined graft loss or death with the lowest pretransplant serum creatinine (HR: 2.16 [1.08 to 4.35], P = 0.03), whereas the highest pretransplant serum creatinine exhibited 22% lower risk of posttransplant adverse outcomes (HR: 0.78 [0.59 to 1.02], P = 0.06). Every 1-mg/dl increase of pretransplant serum creatinine was associated with 6% lower combined risk of death or graft failure when adjusted for BMI and other covariates (HR: 0.94 [0.91 to 0.97], P < 0.001) (Table 4). Sensitivity analyses after adjusting for ten pre-existing comorbid states found similar results (data not shown).

We also categorized renal transplant recipients into four groups on the basis of their pretransplant BMI and serum creatinine levels being above or below the median value of these measures (26 kg/m2 and 10.5 mg/dl, respectively), leading to two concordant (high/high and low/low) and two discordant (high/low and low/high) groups (see Table e7 in the Appendix). The posttransplant death HRs are shown in Figure 3. Compared with the low-creatinine and low-BMI groups (reference), the groups with high creatinine and high BMI had 34% lower adjusted death risk (HR: 0.66 [0.49 to 0.88], P < 0.01) (Figure 3 and Table e8).

Figure 3.

HRs (and 95% confidence intervals) of graft-censored death across BMI and creatinine categories (subgroup are based on cutoff levels according to the median values of pretransplant BMI and creatinine levels) using Cox regression analyses in 10,090 MHD patients who underwent renal transplantation and were observed over a 6-year observation period (July 2001 to June 2007).

Discussion

In 10,090 kidney transplant recipients with comprehensive pretransplant data as MHD patients who were followed for up to 6 years posttransplantation, low pretransplant BMI (<22 kg/m2) showed a trend toward higher posttransplant mortality, whereas obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) was not associated with mortality, albeit it showed a tend toward higher graft loss. Additionally higher pretransplant serum creatinine, a surrogate of muscle mass, was associated with lower mortality and graft loss in that there was a 2.2-fold increased risk of combined death or graft loss with the pretransplant serum creatinine <4 mg/dl, whereas a pretransplant serum creatinine ≥14 mg/dl exhibited 22% greater graft and patient survival when compared with the reference pretransplant serum creatinine of 8 to <10 mg/dl. Assuming that a higher pretransplant serum creatinine value in MHD patients is a surrogate of larger muscle mass and/or better nutritional status, our findings may have major clinical and public health implications, especially in providing care to renal transplant waitlisted patients.

Previous reports have described conflicting associations between BMI and various outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Early studies showed higher risk of postoperative complications (15) and early surgical wound infections (6) in obese patients. Lentine et al. reported higher incidence of cardiovascular (heart failure and atrial fibrillation) and early postoperative complications in obese versus nonobese patients (5). However, others did not find any association between pretransplant BMI and mortality (7–9,30). Chang et al. reported that obesity per se was not associated with poorer kidney transplant outcomes, although it was associated with factors that led to poorer graft and patient survival (31). Being underweight was associated with late graft failure, mainly because of chronic allograft nephropathy (31). Moreover, patients with a BMI ≥30 receiving single pediatric kidneys had better death-censored graft survival rates when compared with nonobese patients (32). Zaydfudim et al. reported that pretransplant overweight and obese status did not affect physical quality of life after kidney transplantation (33).

Somewhat contrary to our findings, Meier-Kreische et al. reported U-shaped risk patterns such that high and low BMI were related to increased risk of death and graft failure (34), and Gore et al. found graded bivariate increases in the risk of delayed graft function, prolonged hospitalization, early graft loss, and graft failure with higher BMI level (35). However, the former study examined the U.S. Renal Data System database between 1988 and 1997, whereas the latter study used the United Network of Organ Sharing database between 1997 and 1999. During the aforementioned period, the immunosuppressive protocols were different (e.g., no tacrolimus was available). Moreover, the latter cohort was younger and had less diabetic and African-American patients.

Very obese patients are frequently denied transplant waitlisting or are advised to lose weight before being reconsidered (14). However, accumulating evidence (including the results presented here) suggest that obesity is not associated with poor long-term clinical outcomes (36–38). Moreover, low BMI or low serum creatinine as a surrogate of low muscle mass and their decreases over time are associated with increased death risk in transplant waitlisted dialyzed patients (21). Because healthier (obese or nonobese) MHD patients are usually preferred for transplantation, our data may be confounded by this selection bias. In MHD patients, lower BMI is associated with higher mortality (39). In our MHD patient cohort, high BMI was not associated with unfavorable posttransplant outcomes. Hence, if our findings can be confirmed by other studies, high BMI should not be a contraindication of transplantation. Nevertheless, the study presented here is unable to examine the question as to whether weight loss before transplantation improves mortality risk or not, although recently it has been suggested that weight change before transplantation had no favorable effect on survival or graft loss (7). Clearly, prospective studies assessing the effect of pretransplant weight loss strategies on long-term outcomes after kidney transplantation are needed. BMI per se may not be an appropriate measure to characterize nutritional status, body composition, obesity, or muscle mass in dialysis patients (16,17,40,41). To better characterize nutritional status, additional parameters such as waist circumference or serum creatinine can be used (17,19–22). It has been suggested that serum creatinine may better reflect muscle mass under steady-state conditions than BMI (17,19–22).

Our findings pertaining to muscle mass are in agreement with some previous studies. Oterdoom et al. found that higher muscle mass, assessed by 24-hour urine creatinine excretion, is associated with better survival after kidney transplantation (42). In dialysis patients low serum creatinine is a marker for protein-energy wasting (43), which is a strong predictor of mortality (44,45) and anemia (46) in renal transplant recipients. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has examined the effect of pretransplant serum creatinine in MHD patients on outcomes after kidney transplantation. Our results suggest that greater or lesser pretransplant muscle mass has a favorable or unfavorable effect on posttransplant outcome, respectively. It is currently not known if improving nutritional status, including increasing BMI and muscle mass before kidney transplantation, improves outcomes. Further studies are needed to answer this question.

Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) showed a nonsignificant trend toward higher graft-rejection rates in our study (Figure 2B). Bosma et al. reported that higher BMI is independently associated with higher GFR and filtration fraction 1 year after transplantation, suggesting the presence of glomerular hyperfiltration with altered afferent-efferent balance (47), which may have played a role in the higher registered rejection rates seen in our study. Further studies are needed to confirm this observation.

Our study is notable for its large sample size, and several important pre- and posttransplant covariates were accounted for in the multivariate analyses. However, like all observational studies, ours too cannot prove causality. Repeated posttransplant measures of weight and creatinine as well as immunosuppressive and other regimens were not available in the SRTR database, but in the full model we did adjust for several transplant-related variables. Patients who were excluded from analyses were likely different from the included ones, but their proportion was relatively small. The variables we used as surrogates for body composition (BMI and serum creatinine) are clearly not ideal. Our study cannot differentiate between intentional and spontaneous weight loss. We are not aware of the potential reasons for weight change, including intercurrent illness or weight-losing interventions such as diet, exercise, or weight loss medication. However, quick and uncontrolled interventions to alter BMI often transiently affect weight (7).

In conclusion, in our large and contemporary national database of over 10,000 renal transplant recipients, pretransplant low BMI showed a trend toward higher posttransplant mortality, and lower pretransplant serum creatinine level, a potential surrogate of sarcopenia, was associated with the unfavorable posttransplant outcomes. These findings may have important implications in providing medical care to tens of thousands of renal transplant waitlisted patients. Additional studies are needed to better understand the association between obesity, muscle mass, and other body compositions and transplant outcomes. Until then, we caution against categorical recommendation of weight loss to apparently obese dialysis patients as a requirement for transplant waitlisting.

Disclosures

Dr. Nissenson is an employee of DaVita, Inc. Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh is the medical director of DaVita Harbor-UCLA Medical Foundation, Inc., in Long Beach, California. The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Robert Lehn at DaVita Laboratories in Deland, Florida, Mr. Joe Weldon from DaVita Informatics for proving the national database, and Mr. Chris Rucker and Dr. Mahesh Krishnan from DaVita Clinical Research for their continued support. The study was supported by K.K.Z.'s research grant from the American Heart Association (0655776Y). K.K.Z.'s other funding sources include the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease of the National Institute of Health (R01 DK078106), a research grant from DaVita Clinical Research, and a philanthropic grant from Mr. Harold Simmons. M.Z.M. received grants from the National Research Fund (NKTH-OTKA-EU 7KP-HUMAN-MB08-A-81231), was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (2008 to 2011), and is a recipient of the Hungarian Eötvös Scholarship (MÖB/66–2/2010).

Footnotes

Supplemental information for this article is available online at www.cjasn.org.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Interpreting Body Composition in Kidney Transplantation: Weighing Candidate Selection, Prognostication, and Interventional Strategies to Optimize Health,” on pages 1238–1240.

References

- 1. Holley JL, Shapiro R, Lopatin WB, Tzakis AG, Hakala TR, Starzl TE: Obesity as a risk factor following cadaveric renal transplantation. Transplantation 49: 387–389, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pirsch JD, Armbrust MJ, Knechtle SJ, D'Alessandro AM, Sollinger HW, Heisey DM, Belzer FO: Obesity as a risk factor following renal transplantation. Transplantation 59: 631–633, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pischon T, Sharma AM: Obesity as a risk factor in renal transplant patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 14–17, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ghahramani N, Reeves WB, Hollenbeak C: Association between increased body mass index, calcineurin inhibitor use, and renal graft survival. Exp Clin Transplant 6: 199–202, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lentine KL, Rocca-Rey LA, Bacchi G, Wasi N, Schmitz L, Salvalaggio PR, Abbott KC, Schnitzler MA, Neri L, Brennan DC: Obesity and cardiac risk after kidney transplantation: Experience at one center and comprehensive literature review. Transplantation 86: 303–312, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lynch RJ, Ranney DN, Shijie C, Lee DS, Samala N, Englesbe MJ: Obesity, surgical site infection, and outcome following renal transplantation. Ann Surg 250: 1014–1020, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Guerra G, Reed AI, Johnson RJ, Weiner ID, Oberbauer R, Harman JS, Hemming AW, Meier-Kriesche HU: A “weight-listing” paradox for candidates of renal transplantation? Am J Transplant 7: 550–559, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Howard RJ, Thai VB, Patton PR, Hemming AW, Reed AI, Van der Werf WJ, Fujita S, Karlix JL, Scornik JC: Obesity does not portend a bad outcome for kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 73: 53–55, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson DW, Isbel NM, Brown AM, Kay TD, Franzen K, Hawley CM, Campbell SB, Wall D, Griffin A, Nicol DL: The effect of obesity on renal transplant outcomes. Transplantation 74: 675–681, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bennett WM, McEvoy KM, Henell KR, Valente JF, Douzdjian V: Morbid obesity does not preclude successful renal transplantation. Clin Transplant 18: 89–93, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Massarweh NN, Clayton JL, Mangum CA, Florman SS, Slakey DP: High body mass index and short- and long-term renal allograft survival in adults. Transplantation 80: 1430–1434, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scandling JD: Kidney transplant candidate evaluation. Semin Dial 18: 487–494, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Modanlou KA, Muthyala U, Xiao H, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR, Brennan DC, Abbott KC, Graff RJ, Lentine KL: Bariatric surgery among kidney transplant candidates and recipients: Analysis of the United States renal data system and literature review. Transplantation 87: 1167–1173, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holley JL, Monaghan J, Byer B, Bronsther O: An examination of the renal transplant evaluation process focusing on cost and the reasons for patient exclusion. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 567–574, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olarte IG, Hawasli A: Kidney transplant complications and obesity. Am J Surg 197: 424–426, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Postorino M, Marino C, Tripepi G, Zoccali C: Abdominal obesity and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 1265–1272, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Noori N, Kopple JD, Kovesdy CP, Feroze U, Sim JJ, Murali SB, Luna A, Gomez M, Luna C, Bross R, Nissenson AR, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Mid-arm muscle circumference and quality of life and survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2258–2268, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kovesdy CP, Czira ME, Rudas A, Ujszaszi A, Rosivall L, Novak M, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Molnar MZ, Mucsi I: Body mass index, waist circumference and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 10: 2644–2651, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Noori N, Kovesdy CP, Dukkipati R, Kim Y, Duong U, Bross R, Oreopoulos A, Luna A, Benner D, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Survival predictability of lean and fat mass in men and women undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Clin Nutr 92: 1060–1070, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noori N, Kovesdy CP, Bross R, Lee M, Oreopoulos A, Benner D, Mehrotra R, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Novel equations to estimate lean body mass in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 130–139, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Molnar MZ, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Bunnapradist S, Sampaio MS, Jing J, Krishnan M, Nissenson AR, Danovitch GM, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Associations of body mass index and weight loss with mortality in transplant-waitlisted maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Transplant 2011, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Oreopoulos A, Noori N, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Krishnan M, Kopple JD, Mehrotra R, Anker SD: The obesity paradox and mortality associated with surrogates of body size and muscle mass in patients receiving hemodialysis. Mayo Clin Proc 85: 991–1001, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Molnar MZ, Lukowsky LR, Streja E, Dukkipati R, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Blood pressure and survival in long-term hemodialysis patients with and without polycystic kidney disease. J Hypertens 28: 2475–2484, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Norris KC, Mehrotra R, Nissenson AR, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Association of cumulatively low or high serum calcium levels with mortality in long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 32: 403–413, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Nissenson AR, Mehrotra R, Streja E, Van Wyck D, Greenland S, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Association of hemodialysis treatment time and dose with mortality and the role of race and sex. Am J Kidney Dis 55: 100–112, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Mehrotra R, Lukowsky LR, Streja E, Ricks J, Jing J, Nissenson AR, Greenland S, Norris KC: Impact of race on hyperparathyroidism, mineral disarrays, administered vitamin D mimetic, and survival in hemodialysis patients. J Bone Miner Res 25: 2448–2458, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Kilpatrick RD, McAllister CJ, Shinaberger CS, Gjertson DW, Greenland S: Association of morbid obesity and weight change over time with cardiovascular survival in hemodialysis population. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 489–500, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kilpatrick RD, Kuwae N, McAllister CJ, Alcorn H, Jr, Kopple JD, Greenland S: Revisiting mortality predictability of serum albumin in the dialysis population: Time dependency, longitudinal changes and population-attributable fraction. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 1880–1888, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shinaberger CS, Greenland S, Kopple JD, Van Wyck D, Mehrotra R, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Is controlling phosphorus by decreasing dietary protein intake beneficial or harmful in persons with chronic kidney disease? Am J Clin Nutr 88: 1511–1518, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marcen R, Fernandez A, Pascual J, Teruel JL, Villafruela JJ, Rodriguez N, Martins J, Burgos FJ, Ortuno J: High body mass index and posttransplant weight gain are not risk factors for kidney graft and patient outcome. Transplant Proc 39: 2205–2207, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chang SH, Coates PT, McDonald SP: Effects of body mass index at transplant on outcomes of kidney transplantation. Transplantation 84: 981–987, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Balamuthusamy S, Paramesh A, Zhang R, Florman S, Shenava R, Islam T, Wagner J, Killackey M, Alper B, Simon EE, Slakey D: The effects of body mass index on graft survival in adult recipients transplanted with single pediatric kidneys. Am J Nephrol 29: 94–101, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zaydfudim V, Feurer ID, Moore DR, Moore DE, Pinson CW, Shaffer D: Pre-transplant overweight and obesity do not affect physical quality of life after kidney transplantation. J Am Coll Surg 210: 336–344, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meier-Kriesche HU, Arndorfer JA, Kaplan B: The impact of body mass index on renal transplant outcomes: A significant independent risk factor for graft failure and patient death. Transplantation 73: 70–74, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gore JL, Pham PT, Danovitch GM, Wilkinson AH, Rosenthal JT, Lipshutz GS, Singer JS: Obesity and outcome following renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 6: 357–363, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lentine KL, Xiao H, Brennan DC, Schnitzler MA, Villines TC, Abbott KC, Axelrod D, Snyder JJ, Hauptman PJ: The impact of kidney transplantation on heart failure risk varies with candidate body mass index. Am Heart J 158: 972–982, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glanton CW, Kao TC, Cruess D, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC: Impact of renal transplantation on survival in end-stage renal disease patients with elevated body mass index. Kidney Int 63: 647–653, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pelletier SJ, Maraschio MA, Schaubel DE, Dykstra DM, Punch JD, Wolfe RA, Port FK, Merion RM: Survival benefit of kidney and liver transplantation for obese patients on the waiting list. Clin Transpl: 77–88, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leavey SF, McCullough K, Hecking E, Goodkin D, Port FK, Young EW: Body mass index and mortality in ‘healthier’ as compared with ‘sicker’ haemodialysis patients: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 2386–2394, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kuwae N, Wu DY, Shantouf RS, Fouque D, Anker SD, Block G, Kopple JD: Associations of body fat and its changes over time with quality of life and prospective mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr 83: 202–210, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bross R, Chandramohan G, Kovesdy CP, Oreopoulos A, Noori N, Golden S, Benner D, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Comparing body composition assessment tests in long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 55: 885–896, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oterdoom LH, van Ree RM, de Vries AP, Gansevoort RT, Schouten JP, van Son WJ, Homan van der Heide JJ, Navis G, de Jong PE, Gans RO, Bakker SJ: Urinary creatinine excretion reflecting muscle mass is a predictor of mortality and graft loss in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 86: 391–398, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fouque D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple J, Cano N, Chauveau P, Cuppari L, Franch H, Guarnieri G, Ikizler TA, Kaysen G, Lindholm B, Massy Z, Mitch W, Pineda E, Stenvinkel P, Trevino-Becerra A, Wanner C: A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 73: 391–398, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Molnar MZ, Czira ME, Rudas A, Ujszaszi A, Lindner A, Fornadi K, Kiss I, Remport A, Novak M, Kennedy SH, Rosivall L, Kovesdy CP, Mucsi I: Association of the malnutrition-inflammation score with clinical outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 2011, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Molnar MZ, Keszei A, Czira ME, Rudas A, Ujszaszi A, Haromszeki B, Kosa JP, Lakatos P, Sarvary E, Beko G, Fornadi K, Kiss I, Remport A, Novak M, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Mucsi I: Evaluation of the malnutrition-inflammation score in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 102–111, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Molnar MZ, Czira ME, Rudas A, Ujszaszi A, Haromszeki B, Kosa JP, Lakatos P, Beko G, Sarvary E, Varga M, Fornadi K, Novak M, Rosivall L, Kiss I, Remport A, Goldsmith DJ, Kovesdy CP, Mucsi I: Association between the malnutrition-inflammation score and post-transplant anaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bosma RJ, Kwakernaak AJ, van der Heide JJ, de Jong PE, Navis GJ: Body mass index and glomerular hyperfiltration in renal transplant recipients: Cross-sectional analysis and long-term impact. Am J Transplant 7: 645–652, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]