Abstract

Etoposide is a widely prescribed anticancer drug that stabilizes covalent topoisomerase II-cleaved DNA complexes. The drug contains a polycyclic ring system (rings A–D), a glycosidic moiety at C4, and a pendant ring (E–ring) at C1. Interactions between human topoisomerase IIα and etoposide in the binary enzyme-drug complex appear to be mediated by substituents on the A-, B-, and E-rings of etoposide. These protein-drug contacts in the binary complex have predictive value for the actions of etoposide within the ternary topoisomerase IIα-drug-DNA complex. Although the D-ring of etoposide does not appear to contact topoisomerase IIα in the binary complex, etoposide derivatives with modified D-rings display reduced cytotoxicity against murine leukemia cells [Meresse et al. (2003) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 13, 4107]. This finding suggests that alterations in the D-ring may affect etoposide activity towards topoisomerase IIα in the ternary enzyme-drug-DNA complex. Therefore, to address the potential contributions of the D-ring to the activity of etoposide, drug derivatives in which the C13 carbonyl was moved to the C11 position (retroetoposide and retroDEPT) or the D-ring was opened (D-ring diol) were characterized. All of the D-ring alterations diminished the ability of etoposide to enhance DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα in vitro and in cultured cells. They also decreased etoposide binding in the ternary enzyme-drug-DNA complex and altered sites of enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage. Based on these findings, we propose that the D-ring of etoposide has important interactions with DNA in the ternary topoisomerase II cleavage complex.

Etoposide is a highly successful anticancer agent that has been used to treat a variety of blood-borne and solid human malignancies for nearly thirty years (1–4). The drug is a derivative of podophyllotoxin, a naturally occurring antimitotic agent from May apples (1, 5). Etoposide kills cells by stabilizing covalent topoisomerase II-cleaved DNA complexes that are formed during the DNA strand passage reaction of the enzyme (6–9). These transient “cleavage complexes” are converted to permanent DNA strand breaks by collisions with DNA tracking systems, which generate chromosomal aberrations, destabilize the genome, and trigger cell death pathways (7–12). Because etoposide converts topoisomerase II to a cellular toxin, it is referred to as a topoisomerase II poison (6–9).

Humans encode two closely related isoforms of topoisomerase II, topoisomerase IIα and topoisomerase IIβ (13–16). The individual contributions of these isoforms to the clinical efficacy of etoposide have yet to be determined. However, recent evidence suggests that topoisomerase IIα may play a more prominent role in mediating the cytotoxic effects of topoisomerase II-targeted anticancer drugs (17–19). Coupled with the fact that the concentration of topoisomerase IIα is generally higher in malignant as compared to corresponding normal tissues, most studies of etoposide action have focused on the α isoform (20–22).

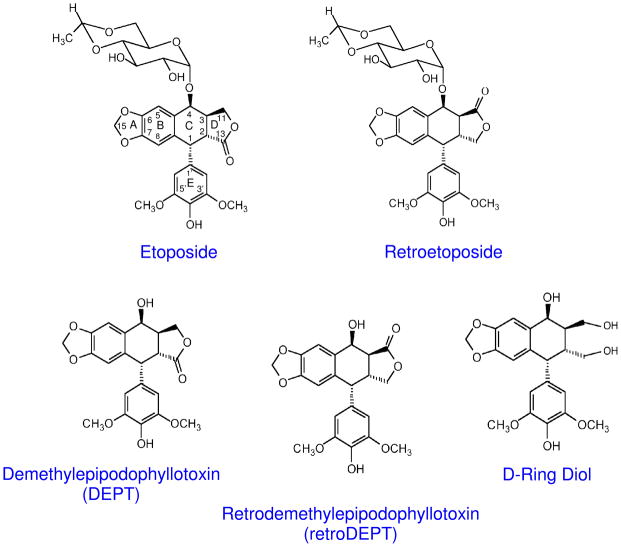

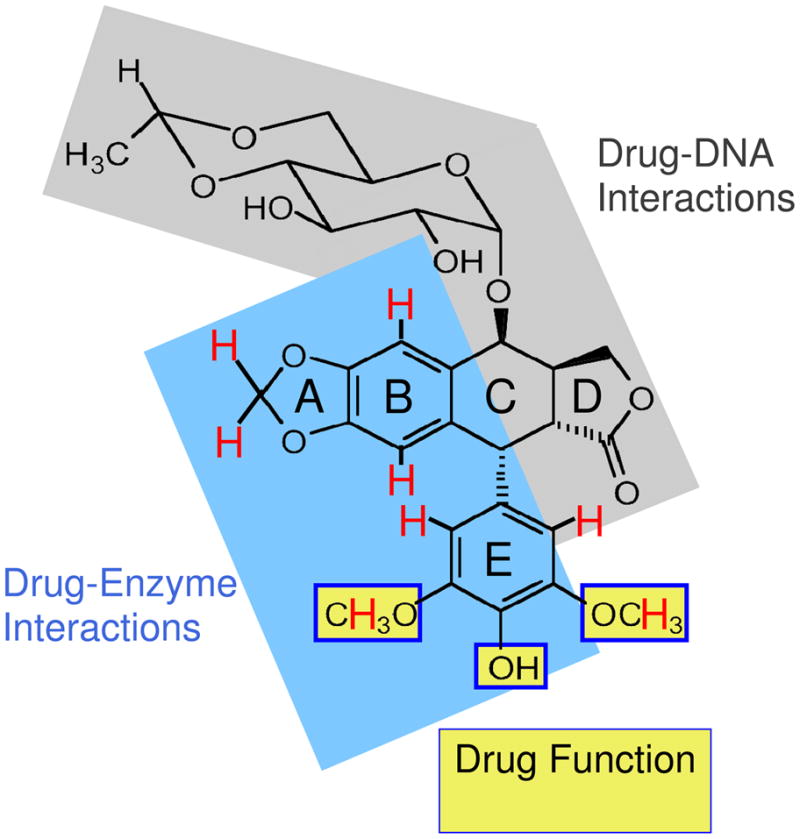

Previous studies indicate that interactions between topoisomerase II and etoposide are critical for drug activity and mediate the entry of etoposide into the ternary enzyme-drug-DNA complex (23–26). Therefore, substituents on etoposide that contact topoisomerase II in the binary enzyme-drug complex have been identified by STD 1H NMR spectroscopy (25, 26). These substituents include the C15 geminal protons of the A–ring, the C5 and C8 protons of the B–ring, the C2′ and C6′ protons of the pendant E–ring, and the 3′– and 5′–methoxyl protons of the Ering (Figure 1). In contrast, no protein contacts have been observed for the C1 and C4 protons of the C-ring, the C2 and C3 protons that bridge the C- and D-rings, the C11 protons of the D-ring, and any protons on the C4 glycosidic moiety. An identical set of drug contacts were seen in a binary complex between topoisomerase IIα and DEPT, an etoposide derivative that lacks the C4 glycosidic group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of etoposide, retroetoposide, DEPT, retroDEPT and the D-ring diol.

Protein-drug contacts in the binary complex have predictive value for the actions of etoposide within the ternary topoisomerase II-drug-DNA complex (25, 26). Opening of the Aring or altering the 3′, 4′, or 5′ substituents of the E-ring dramatically decreases the efficacy of etoposide, but does not affect the specificity of DNA cleavage (25, 26). Thus, it was concluded that etoposide interacts with topoisomerase II through the A-, B-, and E-rings. Conversely, the loss of the C4 glycosidic group in DEPT has relatively little effect on the ability of the drug to enhance topoisomerase II-mediated DNA scission, but does induce subtle changes in cleavage specificity and site utilization (26). Consequently, it has been suggested that the C4 glycoside, along with the D-ring, may mediate interactions with DNA in the cleavage complex (26).

Therefore, to explore potential interactions between the D-ring and DNA during topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage, a series of etoposide derivatives, including retroetoposide, retroDEPT, and the D-ring diol were characterized. Results indicate that D-ring alterations diminish the ability of etoposide to enhance DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα in vitro and in cultured human cells. They also decrease etoposide binding in the ternary enzyme-drug-DNA complex and alter sites of enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage. Based on these findings, it is concluded that the D-ring of etoposide has important interactions with DNA in the topoisomerase II cleavage complex.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Human topoisomerase IIα was expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and purified as described previously (27, 28). However, in the final step of the purification, topoisomerase IIα was eluted from the phosphocellulose column (P81, Whatman) with buffer containing 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.7), 750 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol. For protein samples that were used in NMR experiments, the elution buffer was made up in D2O (99.9%, Aldrich) instead of H2O. Negatively supercoiled pBR322 plasmid DNA was prepared using a Plasmid Mega Kit (Qiagen) as described by the manufacturer. Etoposide was purchased from Sigma. Retroetoposide, DEPT, retroDEPT, and the D-ring diol were synthesized as described previously (29). All drugs were stored at 4 °C as 20 mM stock solutions in 100% DMSO. Drugs used for NMR experiments were stored in 100% d-DMSO. All other chemicals were analytical reagent grade.

Cleavage of Plasmid DNA by Human Topoisomerase IIα

DNA cleavage reactions were carried out using the procedure of Fortune and Osheroff (30). Unless stated otherwise, assay mixtures contained 150 nM topoisomerase IIα and 10 nM negatively supercoiled pBR322 DNA in a total of 20 μL of cleavage buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM NaEDTA, and 2.5% glycerol] that contained 0 to 200 μM etoposide, retroetoposide, DEPT, retroDEPT, or D-ring diol. DNA cleavage was initiated by the addition of enzyme and mixtures were incubated for 6 min at 37 °C to establish DNA cleavage-ligation equilibria. Enzyme-DNA cleavage intermediates were trapped by adding 2 μL of 5% SDS and 1 μL of 375 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Proteinase K was added (2 μL of 0.8 mg/mL) and reactions were incubated for 30 min at 45 °C to digest the topoisomerase IIα. Samples were mixed with 2 μL of 60% sucrose in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 0.5% bromophenol blue, and 0.5% xylene cyanol FF, heated for 15 min at 45 °C, and subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels in 40 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.3), 2 mM EDTA that contained 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide. DNA cleavage was monitored by the conversion of negatively supercoiled plasmids to linear molecules. DNA bands were visualized by ultraviolet light and quantified using an Alpha Innotech digital imaging system.

DNA Ligation

DNA ligation mediated by topoisomerase IIα was monitored according to the procedure of Byl et al. (31). Topoisomerase IIα DNA cleavage-ligation equilibria were established as described above in the absence of compound or in the presence of 100 μM etoposide, retroetoposide, DEPT, retroDEPT, or D-ring diol. Ligation was initiated by shifting reaction mixtures from 37 to 0 °C, and reactions were stopped at time points up to 30 s by the addition of 2 μL of 5% SDS followed by 1 μL of 375 mM NaEDTA (pH 8.0). Samples were processed and analyzed as described above for plasmid DNA cleavage reactions.

Drug-induced DNA Cleavage Mediated by Topoisomerase IIα in Cultured Human CEM Cells

Human CEM acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (ATCC) were cultured under 5% CO2 at 37 °C in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro by Mediatech, Inc.) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Hyclone) and 2 mM glutamine (Cellgro by Mediatech, Inc.). The In vivo Complex of Enzyme (ICE) bioassay (32, 33) (as modified on the TopoGEN, Inc. website) was employed to determine the ability of 25 μM etoposide, retroetoposide, DEPT, retroDEPT, or D-ring diol to induce topoisomerase IIα-mediated DNA breaks in CEM cells. Exponentially growing cultures were treated with DMSO or drugs for 1 h. Cells (~5 × 106) were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by the immediate addition of 3 mL of 1% sarkosyl. Following gentle dounce homogenization, cell lysates were layered onto a 2 mL cushion of CsCl (1.5 g/mL) and centrifuged in a Beckman NVT 90 rotor at 80,000 rpm (~500,000 × g) for 5.5 h at 20 °C. DNA pellets were isolated, resuspended in 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM EDTA, and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes using a Schleicher and Schuell slot blot apparatus. Covalent cleavage complexes formed between topoisomerase IIα and chromosomal DNA were detected using a polyclonal antibody directed against human topoisomerase IIα (Kiamaya Biochemical Co.) at a 1:1000 dilution.

STD 1H NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectra were generated using conditions similar to those described previously (25, 26). All NMR experiments were performed at 283 K using a Bruker Avance 700 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm cryoprobe with z gradients. NMR buffers contained 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.7), 250 mM KCl, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, and 5 mM MgCl2. Samples (400 μL) contained 5 μM human topoisomerase IIα and 500 μM etoposide, retroetoposide, DEPT, retroDEPT, or D-ring diol and were maintained at 4 °C until data were collected. STD 1H NMR experiments employed a pulse scheme similar to that reported by Mayer and Meyer (34). A 2 s saturation pulse was used for the saturation, with on- and off-resonance irradiation frequencies of 0.5 and −71 ppm, respectively. The water signal was suppressed using excitation sculpting with gradients. For each experiment (on- and off-resonance irradiation), 256 scans were collected with a 2 s recycle time. Difference spectra were prepared by subtracting the on-resonance spectrum from the off-resonance spectrum. Signals resulting in the difference spectrum represent the NOE difference signals generated by the transfer of irradiation energy from the enzyme to the bound ligand. Ligand protons in close spatial proximity with the enzyme displayed larger NOE signals. Mapping of the NOE signals with their proton assignments on the ligand revealed the ligand-binding epitope to human topoisomerase IIα. Spectra were processed using Bruker Topspin software.

Cleavage Site Utilization in Linear Plasmid DNA

DNA cleavage sites were mapped using a modification (35) of the procedure of O’Reilly and Kreuzer (36). The pBR322 DNA substrate was linearized by treatment with HindIII. Terminal 5′-phosphates were removed by treatment with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase and replaced with [32P]phosphate using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. The DNA was treated with EcoRI, and the 4332 bp singly-end-labeled fragment was purified from the small EcoRI-HindIII fragment by passage through a CHROMA SPIN+TE-100 column (Clontech). Reaction mixtures contained 0.7 nM labeled pBR322 DNA and 90 nM human topoisomerase IIα in 20 μL of DNA cleavage buffer supplemented with 0.5 mM ATP in the absence of drug or in the presence of 10 μM etoposide, 25 μM DEPT, or 250 μM retroetoposide, retroDEPT, or D-ring diol. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 6 min at 37 °C and enzyme-DNA cleavage complexes were trapped by the addition of 2 μL of 5% SDS followed by 2 μL of 250 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Proteinase K (2 μL of a 0.8 mg/mL solution) was added, and samples were incubated for 30 min at 45 °C to digest the enzyme. DNA products were ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 6 μL of 40% formamide, 10 mM NaOH, 0.02% xylene cyanol FF, and 0.02% bromophenol blue. Samples were subjected to electrophoresis in denaturing 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gels. Gels were dried in vacuo, and DNA cleavage products were visualized with a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX.

Cleavage Site Utilization in Oligonucleotide Substrates

A 47-bp oligonucleotide corresponding to residues 80–126 of pBR322 and its complement were employed to compare the DNA cleavage site specificity of etoposide to that of retroetoposide (37). Oligonucleotide substrates were prepared on an Applied Biosystems DNA synthesizer. The sequences of the top and bottom strands were 5′-CCGTGTATGAAATCTAACAATX↓CGCTCATCGTCATCCTC-GGCACCGT-3′ and 5′-ACGGTGCCGAGGATGACGATG↓AGCGZATTGTTAGATTTCA-TACACGG-3′, respectively. This substrate contains a single strong cleavage site for topoisomerase II that has been well characterized (38–40). Points of scission are denoted by arrows. Oligonucleotides were prepared that contained a G (found in the wild-type sequence), C, A, or T at the −1 position on the top strand (denoted by the bold X). Complementary bottom strand oligonucleotides contained a C, G, T, or A, respectively, at the position denoted by the bold Z. Single-stranded oligonucleotides were labeled on their 5′-termini using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-32P]ATP (~6000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer LAS). Following labeling and gel purification, complementary oligonucleotides were annealed by incubation at 70°C for 10 min and cooling to 25°C.

DNA cleavage by human topoisomerase IIα was determined as described previously (28). Reaction mixtures contained 220 nM human topoisomerase IIα and 100 nM double-stranded oligonucleotide in 20 μL of cleavage buffer containing 0–500 μM etoposide or retroetoposide. Reactions were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. DNA cleavage products were trapped by the addition of 2 μL of 10% SDS, followed by 1 μL of 375 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Samples were digested with proteinase K, ethanol precipitated, and resolved by electrophoresis in 7 M urea, 14% polyacrylamide gels in 100 mM Tris–borate (pH 8.3), 2 mM EDTA. DNA cleavage products were visualized and quantified on a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Interactions between topoisomerase II and substituents on the A-ring, E-ring, and C4 position of etoposide in the binary enzyme-drug complex (identified by STD 1H NMR spectroscopy) predict the ability of etoposide to stabilize the covalent topoisomerase II-DNA cleavage complex (25, 26). However, retroetoposide and retroDEPT display reduced cytotoxicity (~8– and 32–fold, respectively, as compared to etoposide) against murine leukemia L1210 (29) despite the fact that NMR studies indicate that none of the protons on the D-ring of etoposide (i.e., the C2, C3 and C11 protons) contact human topoisomerase IIα in the binary complex (25, 26). Although differences in drug cytotoxicity may reflect physiological attributes such as uptake or efflux, etc., this finding suggests that alterations in the D-ring of etoposide may affect drug activity towards topoisomerase IIα in the ternary enzyme-drug-DNA complex.

Activity of Etoposide D-Ring Derivatives Against Human Topoisomerase IIα

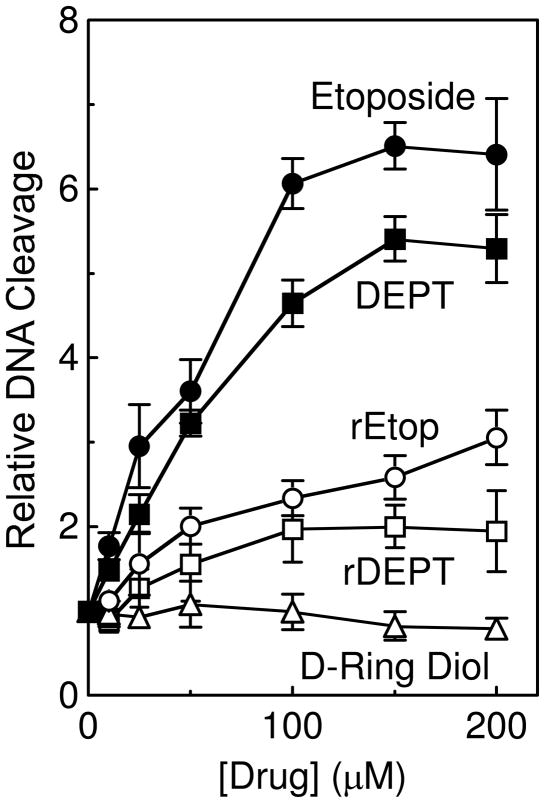

To address the role of the D-ring in etoposide function, the effects of retroetoposide, DEPT, retroDEPT, and the D-ring diol (see Figure 1 for structures) on DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα were compared to that of etoposide (Figure 2). As reported previously (26), the activity of DEPT was ~80–90% that of the parent compound. In contrast, the ability of retroetoposide, retroDEPT, and the D-ring diol to stimulate enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage was reduced substantially. Levels of DNA scission observed in the presence of retroetoposide were ~2– to 3–fold lower than seen with etoposide. The activity of retroDEPT was similarly reduced as compared to DEPT and was lower than that of retroetoposide. Thus, the effects of the two changes in etoposide to generate retroDEPT (i.e., the loss of the C4 glycoside and the transposition of the C13 ketone to the C11 position) appear to be additive. Finally, the D-ring diol displayed no ability to stimulate DNA cleavage mediated by topoisomerase IIα.

Figure 2.

Effects of etoposide derivatives on DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα. Levels of double-stranded DNA cleavage were expressed as a fold–enhancement over reactions that were carried out in the absence of drug. Assay mixtures contained 0–200 μM etoposide (closed circles), DEPT (closed squares), retroetoposide (rEtop, open circles), retroDEPT (rDEPT, open squares), or D-ring diol (open triangles). Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

The above results suggest that the decreased cytotoxicity of retroetoposide and retroDEPT are due, at least in part, to a decreased activity against topoisomerase II. Together with the findings for the D-ring diol, DNA cleavage results provide strong evidence that substituents on the D-ring of etoposide can profoundly affect the ability of the drug to act as a topoisomerase II poison.

It has been suggested that the diminished cellular activity of retroetoposide results from a deleterious interaction between the C4 glycoside and the C11 carbonyl group (29). However, since the decreased activity of retroDEPT compared to DEPT was similar to that for retroetoposide compared to etoposide, this explanation seems unlikely.

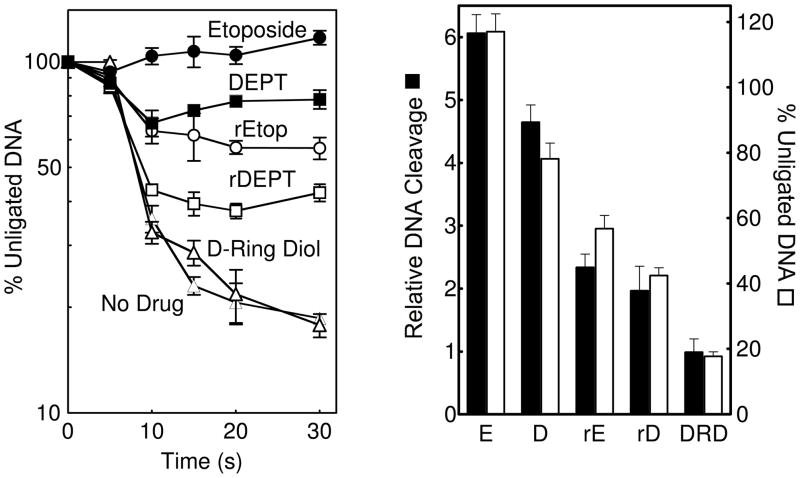

Etoposide increases levels of cleavage complexes by inhibiting the ability of topoisomerase II to ligate DNA (41, 42). Therefore, the effects of the D-ring derivatives on DNA ligation mediated by topoisomerase IIα were determined. As seen in Figure 3 (left panel), all of the compounds displayed a reduced activity compared to etoposide, with the order being the same as seen in DNA cleavage assays (etoposide > DEPT > retroetoposide > retroDEPT ≫ D-ring diol). Moreover, there was a strong correlation between the ability of the drugs to inhibit ligation and increase levels of DNA cleavage (right panel). These results indicate that the derivatives increase levels of topoisomerase II-mediated strand breaks by the same mechanism as that of the parent compound (i.e., inhibition of DNA ligation).

Figure 3.

Left: DNA ligation was examined in the absence of compound (no drug, closed triangles) or in the presence of 100 μM etoposide (closed circles), DEPT (closed squares), retroetoposide (rEtop, open circles), retroDEPT (rDEPT, open squares), or D-ring diol (open triangles). Right: Comparison of DNA cleavage (closed bars, 100 μM drug) and ligation (open bars, 30 s) mediated by human topoisomerase IIα in the presence of etoposide (E), DEPT (D), retroetoposide (rE), retroDEPT (rD), or D-ring diol (DRD). Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

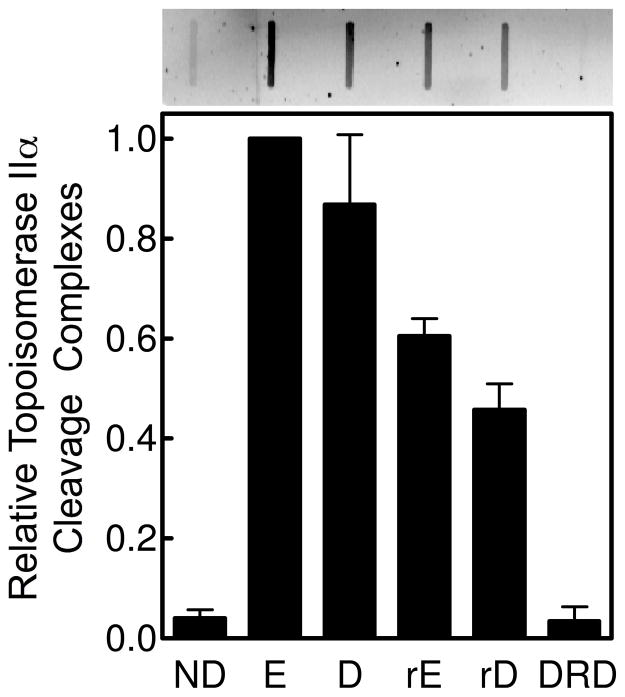

As discussed above, retroetoposide and retroDEPT are cytotoxic to leukemia cells, but are less potent than etoposide (29). Therefore, to determine whether the reduced cytotoxicity of D-ring derivatives correlates with a decreased activity against topoisomerase IIα, we assessed the ability of DEPT, retroetoposide, retroDEPT, and the D-ring diol to induce DNA cleavage by the type II enzyme in cultured human CEM leukemia cells. As seen in Figure 4, drug activity correlated with results of the in vitro DNA cleavage assays: DEPT, retroetoposide, and retroDEPT (in that order) induced reduced cellular levels of cleavage complexes compared to etoposide, and the D-ring diol displayed no activity. These findings strongly suggest that the cytotoxicity of retroetoposide and retroDEPT reflects drug activity against topoisomerase IIα.

Figure 4.

Levels of topoisomerase IIα-DNA cleavage complexes formed in human CEM leukemia cells that were treated with etoposide derivatives. DNA samples (10 μg) from cultures treated with no drug (ND) or 25 μM etoposide (E), DEPT (D), retroetoposide (rE), retroDEPT (rD), or D-ring diol (DRD) for 1 h were blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with a polyclonal antibody directed against human topoisomerase IIα. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments. A representative blot is shown above.

Interactions of Etoposide D-Ring Derivatives with Human Topoisomerase IIα

Although the C2, C3, and C11 protons associated with the D-ring of etoposide do not appear to interact with topoisomerase IIα in the binary complex (25, 26), alterations in the D-ring profoundly affect the ability of the drug to poison topoisomerase IIα in vitro and in cultured human cells (Figures 2 and 4). This dichotomy suggests one of two things: either alterations in the D-ring affect contacts between etoposide and the enzyme in the binary complex, or this portion of etoposide has critical interactions in the ternary complex that are not reflected in the absence of DNA. To address these possibilities, interactions between topoisomerase IIα and retroetoposide, retroDEPT, and the D-ring diol were identified by STD 1H NMR spectroscopy.

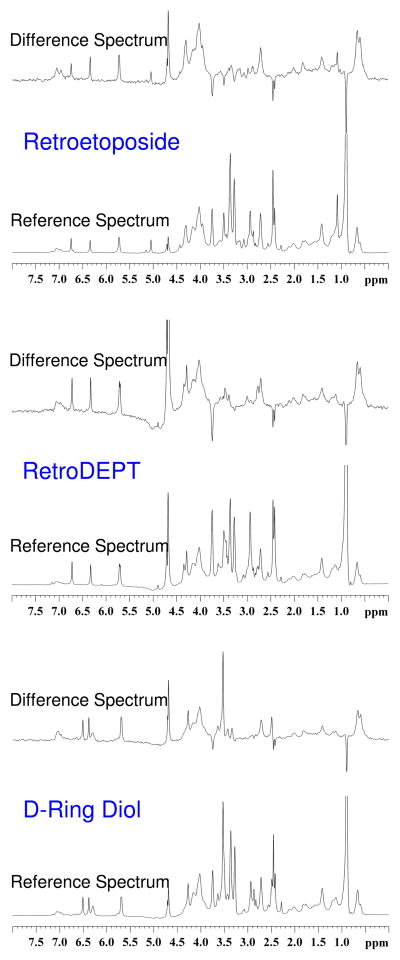

Off-resonance and difference spectra for samples containing topoisomerase IIα and retroetoposide, retroDEPT, and the D-ring diol are shown in Figure 5. Resonances for all visible protons for these drugs, as well as etoposide and DEPT, are given in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Interaction of retroetoposide (top), retroDEPT (middle), and D-ring diol (bottom) with human topoisomerase IIα as determined by STD 1H NMR spectroscopy. Difference and reference (off resonance) spectra are shown for each drug. Spectra are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Table 1.

Drug Substituents that Interact with Human Topoisomerase IIα in the Binary Enzyme-Drug Complex as Determined by STD 1H NMR Spectroscopya

| Etoposide

|

Retroetoposide

|

DEPT

|

RetroDEPT

|

D-Ring Diol

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substituent | Resonance | Substituent | Resonance | Substituent | Resonance | Substituent | Resonance | Substituent | Resonance |

| 1 | 4.39 | 1 | 4.31 | 1 | 4.38 | 1 | 4.26 | 1 | 4.28 |

| 2 | 3.33 | 2 | 3.21 | 2 | 3.10 | 2 | 3.21 | 2 | 2.50 |

| 3 | 2.83 | 3 | 2.88 | 3 | 2.81 | 3 | 2.76 | 3 | 2.5 |

| 4 | 4.82 | 4 | 5.07 | 4 | 4.77 | 4 | 4.84 | 4 | 4.59 |

| 5 | 6.70 | 5 | 6.75 | 5 | 6.70 | 5 | 6.70 | 5 | 6.53 |

| 8 | 6.32 | 8 | 6.33 | 8 | 6.28 | 8 | 6.30 | 8 | 6.32 |

| 11R, 11S | 4.15, 4.20 | 13R, 13S | 3.34, 4.34 | 11R, 11S | 4.09, 4.25 | 13R, 13S | 3.45, 4.32 | ||

| 15R, 15S | 5.70 | 15R, 15S | 5.73 | 15R, 15S | 5.67 | 15R, 15S | 5.68 | 15R, 15S | 5.66 |

| 2′, 6′ | 6.18 | 2′, 6′ | 6.15b | 2′, 6′ | 6.11 | 2′, 6′ | 6.07b | 2′, 6′ | 6.26 |

| 3′, 5′-OCH3 | 3.49 | 3′, 5′-OCH3 | 3.49b | 3′, 5′-OCH3 | 3.45 | 3′, 5′-OCH3 | 3.59b | 3′, 5′-OCH3 | 3.54 |

| 1″ | 4.43 | 3″ | 4.44 | 11-CH2 | 3.44, 3.65 | ||||

| 2″ | 3.07 | 5″ | 3.00 | 13-CH2 | 3.35, 3.53 | ||||

| 3″ | 3.33 | 6″ | 3.37 | ||||||

| 4″ | 3.17 | 7″ | 3.17 | ||||||

| 5″ | 3.24 | 9″, 12″ | 3.08 | ||||||

| 6″, 6″ | 3.42, 4.01 | 10″, 11″ | 3.40, 3.97 | ||||||

| 7″ | 4.70 | 14″, 16″ | 4.64 | ||||||

| −CH3 | 1.10 | 15″ | 1.10 | ||||||

Resonances that display nuclear Overhauser effects in STD 1H NMR spectroscopy experiments along with the substituent protons that they represent are indicated in bold and are underlined.

Indicated resonances were substantially broadened.

With the exception of one additional contact with the enzyme (the C4 proton of the C-ring), the substituents on retroetoposide and retroDEPT that interact with human topoisomerase IIα in the binary complex were the same as those previously described for etoposide and DEPT (25, 26). However, the nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) signals seen for the E-ring protons of both drugs were substantially broader than found with etoposide in the binary complex. This finding suggests that movement of the C13 carbonyl group to the C11 position may alter the conformation around the E-ring of etoposide and affect interactions between this portion of the drug and the enzyme.

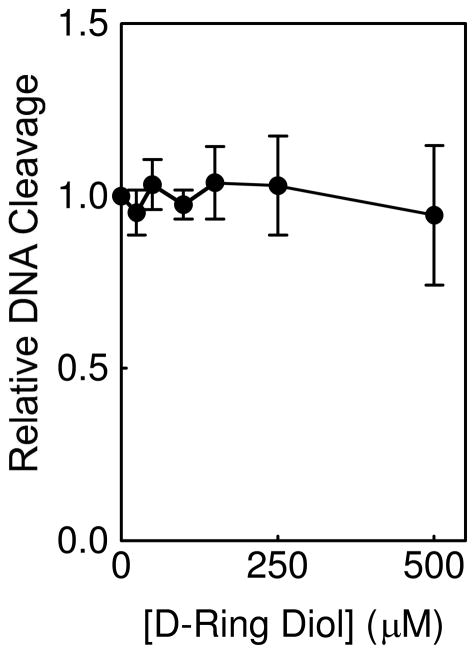

In contrast to retroetoposide and retroDEPT, the substituents on the D-ring diol that contact topoisomerase IIα in the binary complex were identical to those of etoposide and no broadening of the E-ring proton resonances were observed. This result indicates that the loss of the D-ring does not alter drug interactions in the binary complex and implies that the lack of DNA cleavage enhancement induced by this derivative results from a specific difference in drug interactions within the ternary complex. Therefore, a competition assay was carried out to address this possibility. As seen in Figure 6, the D-ring diol was unable to displace 50 μM etoposide from the ternary topoisomerase IIα-DNA cleavage complex, even at concentrations that were 10–fold higher than that of the parent compound. Thus, despite the fact that the D-ring diol and etoposide display similar contacts with topoisomerase IIα in the binary complex, their interactions in the ternary complex (at least with regard to strength) appear to differ. Because the difference between the binary and ternary complex is the presence of DNA, this finding suggests that the D-ring may have important interactions with the double helix in the covalent topoisomerase IIα-drug-DNA cleavage complex.

Figure 6.

Competition between the D-ring diol and etoposide in the ternary complex. Topoisomerase IIα-mediated DNA cleavage in the presence of 50 μM etoposide and increasing concentrations (up to 500 μM) of D-ring diol is shown as fold–enhancement over etoposide alone. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Effects of D-Ring Substitutions on the Specificity of Topoisomerase IIα-mediated DNA Cleavage

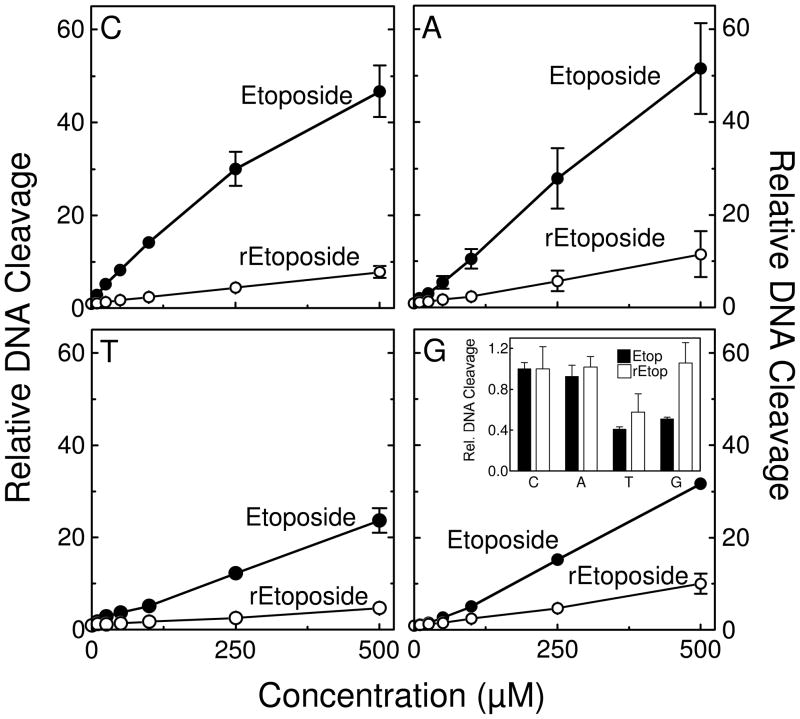

A previous study demonstrated that removal of the C4 glycoside alters the specificity of etoposide-induced DNA cleavage by human topoisomerase IIα (also shown in Figure 7) (26). Consequently, it was proposed that the sugar moiety of etoposide interacts with DNA in the cleavage complex. Because the etoposide D-ring does not appear to contact topoisomerase IIα in the binary complex but modification of this group significantly diminishes drug activity, sites of cleavage were mapped to determine if the D-ring also has the potential to interact with the double helix in the cleavage complex.

Figure 7.

DNA cleavage site specificity and utilization by human topoisomerase IIα in the presence of etoposide derivatives. A singly end-labeled linear 4332 bp fragment of pBR322 was used as the cleavage substrate. An autoradiogram of a polyacrylamide gel is shown. DNA cleavage reactions contained topoisomerase IIα with no drug (Topo), 10 μM etoposide (Etop), 250 μM retroetoposide (rEtop), 25 μM DEPT (DEPT), 250 μM retroDEPT (rDEPT), or 250 μM D-ring diol (DRD). A DNA control (DNA) also is shown. Data are representative of four independent experiments.

As seen in Figure 7, there were substantial differences in the cleavage specificity/site utilization of topoisomerase IIα in the presence of etoposide vs. retroetoposide. Similar differences were seen when comparing cleavage maps generated in the presence of DEPT vs. retroDEPT. In addition, opening of the D-ring (D-ring diol) abolished all sites of drug-induced DNA cleavage. These results indicate that the specificity of etoposide-induced DNA cleavage is governed, at least in part, by the D-ring. Furthermore, results are consistent with the hypothesis that the D-ring contacts DNA in the topoisomerase IIα cleavage complex. Because movement of the C13 carbonyl to the C11 position appears to affect the conformation of the etoposide E-ring, an alternative hypothesis is that D-ring alterations affect cleavage specificity by indirectly changing protein-drug contacts. However, two findings argue against this latter interpretation. First, the D-ring diol displays no ability to induce topoisomerase IIα-mediated DNA cleavage, despite the fact that the protein-drug contacts in the binary complex are the same as those seen with etoposide. Second, a previous study found that derivatization of the etoposide E-ring significantly diminishes levels of drug-induced DNA cleavage, but has no effect on the site specificity of human topoisomerase IIα (25).

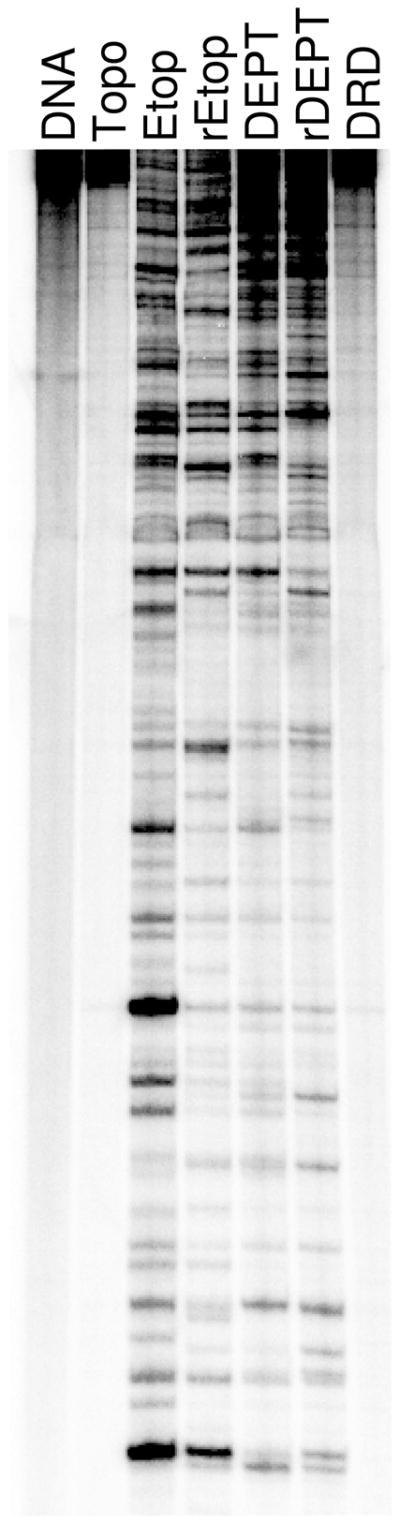

To further examine the effects of D-ring derivatization on the cleavage specificity of the type II enzyme, the ability of etoposide and retroetoposide to induce topoisomerase IIα-mediated DNA cleavage of an oligonucleotide substrate was compared. Etoposide displays specificity for the −1 base relative to the scissile bond and generally prefers to cleave substrates with a C at this position (43, 44). With the oligonucleotide used for cleavage experiments, etoposide preferentially induced cleavage when the substrate contained a −1 C or A (Figure 8). Scission levels dropped ~2–fold when a T or G was present at this position.

Figure 8.

Oligonucleotide sequence specificity of etoposide (closed circles) versus retroetoposide (open circles). Drug titrations were performed using an oligonucleotide substrate that contained a strong cleavage site for human topoisomerase IIα. The oligonucleotide was synthesized with either a C, A, T, or G at the −1 position relative to the scissile bond. The inset in the lower right panel compares DNA cleavage levels induced by 250 μM etoposide (closed bars) or retroetoposide (open bars) relative to cleavage of the oligonucleotide containing a C at the −1 position, which was set at 1 for both drugs. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Compared to etoposide, retroetoposide displays a decreased specificity for a −1 C or A (Figure 8). In fact, levels of topoisomerase IIα-mediated DNA scission with the −1 G substrate were comparable to those seen in the presence of C or A. This finding confirms that changes in the D-ring of etoposide alter the DNA cleavage specificity of the drug.

Conclusions

Although etoposide is in its fourth decade of clinical use, relationships between drug activity and interactions within the binary topoisomerase II-drug complex and the ternary topoisomerase II-drug-DNA complex have been addressed only recently. Based on the results of STD 1H NMR spectroscopy and enzyme-drug binding in the binary complex, as well as drug competition and DNA cleavage in the ternary complex, a model has emerged (Figure 9). In this model, the binding of etoposide to human topoisomerase IIα is driven by interactions with the A–ring, B–ring, and potentially by stacking interactions with the E–ring (25, 26). The E–ring methoxyl groups and the 4′-OH moiety are important for drug function, but do not contribute substantially to enzyme-drug binding or DNA cleavage specificity (25, 26).

Figure 9.

Summary of etoposide substituents that interact with human topoisomerase IIα. Protons that interact with the enzyme (as determined by STD 1H NMR spectroscopy) are shown in red (25, 26). Interactions between hydroxyl protons and the enzyme were obscured by the water peak and could not be visualized. The blue region on etoposide, including portions of the A–, B– and E–rings, is proposed to interact with topoisomerase IIα in the binary drug-enzyme complex. E–ring substituents highlighted with yellow boxes are important for drug function and interact with the enzyme, but do not appear to contribute significantly to binding (25, 26). We propose that interactions between etoposide and DNA in the ternary complex (shaded in gray) are driven primarily by the D-ring, with additional contributions from the C4 sugar.

Neither the C4 gylcoside nor the D-ring of etoposide contact the enzyme in the binary complex (25, 26). While removal of the sugar has little effect on drug activity, it subtly alters the specificity of DNA cleavage. In contrast, D-ring modifications profoundly affect the ability of etoposide to induce DNA scission and alter the cleavage specificity of topoisomerase IIα. Taken together, we propose that interactions between etoposide and DNA in the ternary complex are driven primarily by the D-ring, with additional contributions from the C4 sugar. This hypothesis is supported by recent studies on F14512, an etoposide derivative that replaces the C4 glycoside with a spermine moiety (45–47). The presence of the spermine enhances DNA interactions and increases the potency of the drug against human type II topoisomerases (45–47). Thus, by targeting the C4 moiety and the D-ring, it may be possible to develop novel etoposide derivatives with increased activity and/or altered cleavage specificity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Amanda C. Gentry, Adam C. Ketron, and Katie J. Aldred for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DEPT

4′-demethyl epipodophyllotoxin;

- retroetoposide

11-oxo,13-deoxo-etoposide

- retroDEPT

11-oxo,13-deoxo-4′-demethyl epipodophyllotoxin

- D-ring diol

11,13-O,O-4′-demethyl epipodophyllotoxin

- STD

saturation transfer difference

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser enhancement

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM33944 (NO), Department of Defense grant DOD/CDMRP-BCRP BC095831P1 (DEG), and Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer and ACI ‘Molécules et Cibles Thérapeutiques’ du Ministère de la Recherche (PBA).

References

- 1.Hande KR. Etoposide: four decades of development of a topoisomerase II inhibitor. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1514–1521. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hande KR. Clinical applications of anticancer drugs targeted to topoisomerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:173–184. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holden JA. DNA topoisomerases as anticancer drug targets: from the laboratory to the clinic. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2001;1:1–25. doi: 10.2174/1568011013354859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin EL, Osheroff N. Etoposide, topoisomerase II and cancer. Curr Med Chem Anti-Canc Agents. 2005;5:363–372. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nitiss JL, Liu YX, Hsiung Y. A temperature sensitive topoisomerase II allele confers temperature dependent drug resistance on amsacrine and etoposide: a genetic system for determining the targets of topoisomerase II inhibitors. Cancer Res. 1993;53:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pommier Y, Marchand C. Interfacial inhibitors of protein-nucleic acid interactions. Curr Med Chem Anti-Cancer Agents. 2005;5:421–429. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClendon AK, Osheroff N. DNA topoisomerase II, genotoxicity and cancer. Mut Res. 2007;623:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deweese JE, Osheroff N. The DNA cleavage reaction of topoisomerase II: wolf in sheep’s clothing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:738–748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nitiss JL. Targeting DNA topoisomerase II in cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:338–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baguley BC, Ferguson LR. Mutagenic properties of topoisomerase-targeted drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufmann SH. Cell death induced by topoisomerase-targeted drugs: more questions than answers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:195–211. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sordet O, Khan QA, Kohn KW, Pommier Y. Apoptosis induced by topoisomerase inhibitors. Curr Med Chem Anti-Cancer Agents. 2003;3:271–290. doi: 10.2174/1568011033482378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake FH, Zimmerman JP, McCabe FL, Bartus HF, Per SR, Sullivan DM, Ross WE, Mattern MR, Johnson RK, Crooke ST. Purification of topoisomerase II from amsacrine-resistant P388 leukemia cells. Evidence for two forms of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:16739–16747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drake FH, Hofmann GA, Bartus HF, Mattern MR, Crooke ST, Mirabelli CK. Biochemical and pharmacological properties of p170 and p180 forms of topoisomerase II. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8154–8160. doi: 10.1021/bi00446a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Champoux JJ. DNA topisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velez-Cruz R, Osheroff N. DNA topoisomerases: type II. In: Lennarz W, Lane MD, editors. Encyc Biol Chem. I. Elsevier Science Inc; San Diego: 2004. pp. 806–811. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sehested M, Holm B, Jensen PB. Dexrazoxane for protection against cardiotoxic effects of anthracyclines. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azarova AM, Lyu YL, Lin CP, Tsai YC, Lau JY, Wang JC, Liu LF. Roles of DNA topoisomerase II isozymes in chemotherapy and secondary malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11014–11019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704002104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyu YL, Kerrigan JE, Lin CP, Azarova AM, Tsai YC, Ban Y, Liu LF. Topoisomerase IIβ mediated DNA double-strand breaks: implications in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and prevention by dexrazoxane. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8839–8846. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keith WN, Tan KB, Brown R. Amplification of the topoisomerase II alpha gene in a non-small cell lung cancer cell line and characterisation of polymorphisms at the human topoisomerase IIα and β loci in normal tissue. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer. 1992;4:169–175. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870040211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keith WN, Douglas F, Wishart GC, McCallum HM, George WD, Kaye SB, Brown R. Co-amplification of erbB2, topoisomerase IIα and retinoic acid receptor α genes in breast cancer and allelic loss at topoisomerase I on chromosome 20. Eur J Cancer. 1993;10:1469–1475. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skotheim RI, Kallioniemi A, Bjerkhagen B, Mertens F, Brekke HR, Monni O, Mousses S, Mandahl N, Soeter G, Nesland JM, Smeland S, Kallioniemi OP, Lothe RA. Topoisomerase IIα is upregulated in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and associated with clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4586–4591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burden DA, Kingma PS, Froelich-Ammon SJ, Bjornsti MA, Patchan MW, Thompson RB, Osheroff N. Topoisomerase II-etoposide interactions direct the formation of drug-induced enzyme-DNA cleavage complexes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29238–29244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kingma PS, Burden DA, Osheroff N. Binding of etoposide to topoisomerase II in the absence of DNA: decreased affinity as a mechanism of drug resistance. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3457–3461. doi: 10.1021/bi982855i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilstermann AM, Bender RP, Godfrey M, Choi S, Anklin C, Berkowitz DB, Osheroff N, Graves DE. Topoisomerase II-drug interaction domains: identification of substituents on etoposide that interact with the enzyme. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8217–8225. doi: 10.1021/bi700272u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bender RP, Jablonksy MJ, Shadid M, Romaine I, Dunlap N, Anklin C, Graves DE, Osheroff N. Substituents on etoposide that interact with human topoisomerase IIa in the binary enzyme-drug complex: contributions to etoposide binding and activity. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4501–4509. doi: 10.1021/bi702019z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worland ST, Wang JC. Inducible overexpression, purification, and active site mapping of DNA topoisomerase II from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4412–4416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kingma PS, Greider CA, Osheroff N. Spontaneous DNA lesions poison human topoisomerase IIα and stimulate cleavage proximal to leukemic 11q23 chromosomal breakpoints. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5934–5939. doi: 10.1021/bi970507v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meresse P, Magiatis P, Bertounesque E, Monneret C. Synthesis and antiproliferative activity of retroetoposide. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:4107–4109. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fortune JM, Osheroff N. Merbarone inhibits the catalytic activity of human topoisomerase IIα by blocking DNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17643–17650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byl JA, Fortune JM, Burden DA, Nitiss JL, Utsugi T, Yamada Y, Osheroff N. DNA topoisomerases as targets for the anticancer drug TAS-103: primary cellular target and DNA cleavage enhancement. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15573–15579. doi: 10.1021/bi991791o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subramanian D, Kraut E, Staubus A, Young DC, Muller MT. Analysis of topoisomerase I/DNA complexes in patients administered topotecan. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2097–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byl JA, Cline SD, Utsugi T, Kobunai T, Yamada Y, Osheroff N. DNA topoisomerase II as the target for the anticancer drug TOP-53: mechanistic basis for drug action. Biochemistry. 2001;40:712–718. doi: 10.1021/bi0021838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayer M, Meyer B. Group epitope mapping by saturation transfer difference NMR to identify segments of a ligand in direct contact with a protein receptor. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6108–6117. doi: 10.1021/ja0100120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldwin EL, Byl JA, Osheroff N. Cobalt enhances DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIa in vitro and in cultured cells. Biochemistry. 2004;43:728–735. doi: 10.1021/bi035472f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Reilly EK, Kreuzer KN. A unique type II topoisomerase mutant that is hypersensitive to a broad range of cleavage-inducing antitumor agents. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7989–7997. doi: 10.1021/bi025897m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bromberg KD, Burgin AB, Osheroff N. A two-drug model for etoposide action against human topoisomerase IIα. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7406–7412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sander M, Hsieh T. Double strand DNA cleavage by type II DNA topoisomerase from Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:8421–8428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corbett AH, Zechiedrich EL, Osheroff N. A role for the passage helix in the DNA cleavage reaction of eukaryotic topoisomerase II. A two-site model for enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:683–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kingma PS, Osheroff N. Apurinic sites are position-specific topoisomerase II-poisons. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1148–1155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osheroff N. Effect of antineoplastic agents on the DNA cleavage/religation reaction of eukaryotic topoisomerase II: inhibition of DNA religation by etoposide. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6157–6160. doi: 10.1021/bi00441a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson MJ, Osheroff N. Effects of antineoplastic drugs on the post-strand-passage DNA cleavage/religation equilibrium of topoisomerase II. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1807–1813. doi: 10.1021/bi00221a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pommier Y, Capranico G, Orr A, Kohn KW. Local base sequence preferences for DNA cleavage by mammalian topoisomerase II in the presence of amsacrine or teniposide. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5973–5980. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.21.5973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Capranico G, Binaschi M. DNA sequence selectivity of topoisomerases and topoisomerase poisons. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:185–194. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barret JM, Kruczynski A, Vispe S, Annereau JP, Brel V, Guminski Y, Delcros JG, Lansiaux A, Guilbaud N, Imbert T, Bailly C. F14512, a potent antitumor agent targeting topoisomerase II vectored into cancer cells via the polyamine transport system. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9845–9853. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kruczynski A, Vandenberghe I, Pillon A, Pesnel S, Goetsch L, Barret JM, Guminski Y, Le Pape A, Imbert T, Bailly C, Guilbaud N. Preclinical activity of F14512, designed to target tumors expressing an active polyamine transport system. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:9–21. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gentry AC, Pitts SL, Jablonsky MJ, Bailly C, Graves DE, Osheroff N. Interactions between the etoposide derivative F14512 and human type II topoisomerases: implications for the C4 spermine moiety in promoting enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage. Biochemistry. 2011 doi: 10.1021/bi200094z. in press (epub 3/17/2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]