Abstract

Double anal fin (Da) is a medaka with an autosomal semidominant mutation that causes mirror image duplication of the ventral region concentrating on the caudal region. The chromosomal location of the Da gene and its sequence have remained unknown. We constructed a medaka linkage map as a first step to approach positional cloning of the gene. The segregation analysis was performed on the basis of genetic recombination during female meiosis using 134 random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers, 13 sequence-tagged sites (STSs), 15 polymorphic sequences from known genes, and the Da gene. One hundred forty-six markers from the above markers segregated into 26 linkage groups. The size of the genome was estimated to be 1776 cM in length. We identified four syntenic regions between medaka and zebrafish (and human) by mapping the known genes and found one of them to be located in close proximity to the Da gene. By mapping the region surrounding the Da gene in high resolution, two markers were detected flanking the Da gene at 0.32 and 0.80 cM. The detected markers providing a vital clue to initiate chromosome walking will lead us to the definite location of the Da gene.

Medaka (Oryzias latipes) is a small, egg-laying freshwater fish, and has been used extensively for genetic studies. It has 24 haploid chromosomes in the nucleus (Iriki 1932), nearly the same number as zebrafish (25). Many spontaneous mutants of medaka have been isolated and maintained (Tomita 1975, 1992; Ozato and Wakamatsu 1994). The Double anal fin (Da) is a mutant that has an autosomal semidominant mutation (Tomita 1969, 1975). In the homozygote of Da−/Da−, the dorsal fin is similar in shape to the anal fin, and the caudal fin has a rhombic shape. The iridophores, which are normally located in the belly region, are found on the dorsal side as well as on the ventral side of the trunk in the mutant (Tomita 1975; Fig. 1B). It has been hypothesized from these phenotypes that the dorsal half of the caudal region is a mirror image of the ventral half across the lateral midline and that the Da− mutation causes general ventralization of dorsal structures, which becomes apparent before hatching (Ishikawa 1990; Tamiya et al. 1997). Despite these drastic phenotypes, the homozygote matures, behaves, and reproduces as the wild type.

Figure 1.

Phenotypes of wild-type (+/+) and Da homozygote (Da−/Da−) adult fishes. (A) A wild-type (+/+) adult female (HNI strain). It has normal dorsal and caudal fins. Many bright guanophores are found on the belly. (B) A Da−/Da− homozygote adult male. The dorsal fin is similar in shape to the anal fin and the caudal fin is rhombic. Many bright iridophores are found not only on the belly but also in the dorsal region of the trunk.

At present, there have been no reports on the mutations that cause phenotypes like Da. Recently, large-scale mutagenesis has been conducted and numerous embryonic visible mutations have accumulated in zebrafish (Driever et al. 1996; Haffer et al. 1996). Regarding the dorsoventral patterning, several mutants with defects in eight genes have been isolated and characterized (Hammerschmidt et al. 1996; Mullins et al. 1996). Morphological characteristics associated with these mutants, however, become obvious at an earlier stage than in the Da mutant, and structures or tissues with abnormal phenotypes do not exactly coincide with those of the Da mutant. More important, none of these zebrafish mutants reveal mirror image pattern duplication with respect to the dorsoventral axis, but only show a reduction or expansion of dorsally or ventrally derived structures. From these facts, a causative gene responsible for the Da mutant is supposed to be distinct from those of zebrafish mutants, although there is a possibility that zebrafish phenotypes are derived from partial or different mutations in the zebrafish Da ortholog or in a related gene. Multiple genes that play decisive roles in the dorsoventral patterning have been identified in several species, but a candidate gene for the Da mutant is difficult to predict from any known genes in terms of unique phenotypes in Da. Therefore, the Da mutation is expected to represent a novel gene involved in the dorsoventral patterning and identification of the causative gene will provide new insight into this important embryonic differentiation during vertebrate development.

The development of techniques in handling high molecular weight DNA (such as pulse-field gel electrophoresis, yeast artificial chromosome (YAC), bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC), P1 artificial chromosome (PAC) vectors) has enabled us to search for the causative gene of mutants with positional cloning strategies. This approach first requires the definition of the location of a target gene on a genetic linkage map and identification of tightly linked markers flanking the gene of interest. Genetic analysis of the Da gene has been very limited and linkage relationship of the Da gene to known genes, mutations, or molecular markers has remained to be established.

Genetic maps constructed by the random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) method (Welsh and McClelland 1990; Williams et al. 1990), which requires no previous DNA sequence information, have been reported for many organisms such as Arabidopsis (Reiter et al. 1992), honey bee (Hunt and Page 1995), and zebrafish (Postlethwait et al. 1994; Johnson et al. 1996). In medaka, Wada et al. (1995) constructed a medaka genetic linkage map, based on male meioses. However, this map did not cover the entire medaka genome; 27 linkage groups, three more than the number of medaka haploid chromosomes (24) were identified and 67 markers remained unlinked. In addition, none of known genes were assigned to linkage groups.

In the present study, we constructed a new medaka genetic linkage map based on female meioses with several different polymorphic molecular markers including known genes. We believe that the map becomes more accurate after it is combined with Wada's map. The Da gene was delineated on linkage group (LG) VIII and closely linked markers in the proximity of Da were obtained. These might be useful for chromosome walking. In addition, the possibility of synteny between medaka and human or zebrafish chromosomes is presented.

RESULTS

Polymorphisms of Markers

Three kinds of polymorphic DNA markers (RAPD markers, sequence-tagged sites (STS) markers converted from RAPD, and known genes) were used to construct a linkage map of medaka (O. latipes) in this study. In RAPD analysis, 45% (59 of 131) of primers gave rise to PCR fragments that were specific to the Hôiken-Niigata (HNI) strain. A total of 133 polymorphic RAPD markers were obtained using these primers and could be subjected to segregation analyses.

Sixteen RAPD bands were converted to STS markers (Table 1). Genetic polymorphisms that distinguished between HNI and Da were detected at all of the STS loci examined. Seven of these markers were determined by nucleotide sequences from both strains. Homology search of STS markers in the DNA database using the BLASTN program indicated that only the stsOPX06-2 marker had nucleotide sequence similarity (89.2% identity in 102 nucleotide overlap) to the mouse corresponding gene (producing ET putative translation product mRNA; AF015191). The degree of nucleotide polymorphisms existing in anonymous STS markers was calculated as one polymorphism at every ∼30 bp (Table 2).

Table 1.

STS Markers

| Marker name | GenBank Acc. no | Primer pairsa | Size | Polymorphism | LG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stsB07-3 | AB030355 | CCAGATCCACCCCAGCAGAA | 445 | sequence-specific PCR amplification | VIII |

| AB030356 | CAGGAGTTTCCTGACATGCG | ||||

| GCTCACTGTTCTGGATCATC | 335/334 | size | |||

| CACGACACCAAGAGAAACTC | |||||

| stsM02-5 | AB030357 | ACGGAGCAAAGACGGACAA | 451 | RFLP after cutting with HinfI | VIII |

| AB030358 | TGCCAGTCAGGAGTCTGACTA | ||||

| stsM63-1 | AB030359 | TTGGGTGGGCAGGAAAGAT | 405 | RFLP after cutting with HinfI | VIII |

| ACGCAAAAAGCAACACAGGG | |||||

| stsM90-3 | AB030360 | CCTGCAGCATAGAAGCCTTTG | 491/475 | Size | VIII |

| AB030361 | AAGGGAATGTCCAAAGGAGC | ||||

| stsNTU29-3 | AB030362 | GCTGACTCCTGGTATGAAG | 773 | RFLP after cutting with SfaNI | VIII |

| GAACTCTATAGCAGGTGAGC | |||||

| stsOPQ05-1 | AB030363 | AATCTGCCAGGATCCAGTCA | 556 | RFLP after cutting with HinfI | I |

| CCTACGGAGCGGTCATTTCTGTAG | |||||

| stsOPR04-1 | AB030364 | GCAGGCATCATTCATAATGC | 458 | RFLP after cutting with AluI | I |

| AB030365 | GAGTTGCTGCAAGGTCAAAG | ||||

| stsOPS11-1b | AB030366 | CTGCTCCACCGTAGAAAGCC | 341 | sequence-specific PCR amplification | VIII |

| AB030367 | CACTCGTTCAGGTCGTTCAG | ||||

| CGAAGAACTATGTGCTTTCC | 629/587 | size | |||

| TAGGACCACTGTGGACTTAG | |||||

| stsOPU19-2 | AB030368 | CATCATTCAGTCCCCATAA | 418 | sequence-specific PCR amplification | XVI |

| TGGAGGGACAAGATGCACAG | |||||

| stsOPU19-3 | AB030369 | GTTACTCTGAGGGGACAAAC | 310 | RFLP after cutting with MspI | IX |

| ATGACAAAGGACGGCGAACG | |||||

| stsOPU19-4 | AB030370 | CGCTGAAATCAGGCTCAGG | 470/418 | size | IX |

| AAAGAGGCAGAGAGGATCTC | |||||

| stsOPV10-1 | AB030371 | GGTGTGATACGTCTTATAGG | 493 | RFLP after cutting with MspI | IV |

| GGAACAATCAGGGCTGAGTG | |||||

| stsOPV10-2b | AB030372 | GAAGGAAACAGCCTCATCAC | 454 | RFLP after cutting with AluI | VIII |

| GTTCCAGTTTCCTACAGCTG | |||||

| stsOPX06-1b | AB030373 | GAGACAATCCTTTCCCATTC | 612 | RFLP after cutting with AluI | VIII |

| GCTCCAGATCCGCAAAGTGC | |||||

| stsOPX06-2 | AB030374 | TGAAGGATGGCAGGCGTGTC | 669 | RFLP after cutting with BamHI | unlinked |

| AB030375 | GAGGCGTTCATCACTCCCAG | ||||

| stsOPZ20-3 | AB030376 | GAATACGTGTGGAGTCAACC | 388 | RFLP after cutting with SspI | VIII |

| AB030377 | GAAGCATCCTTAGGAATGGG |

Primer pairs shown in italics were used for sequencing but not for segregation analysis.

These markers were used only for high resolution mapping around the Da gene.

Table 2.

Nucleotide Polymorphisms Between the HNI Strain and the Da Mutant

| Size compared (bp) | Single-nucleotide polymorphisma | Insertions or deletions | Total No. of polymorphisms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anonymous STS markers | 2446 | 77 | 5 | 82 |

| frequency (poly./bp) | 1/32 | 1/489 | 1/30 | |

| Known genes (intron) | 1887 | 50 | 8 | 58 |

| frequency (poly./bp) | 1/38 | 1/236 | 1/33 | |

| Known genes (exon)b | 3241 | 27 (3) | 0 | 27 |

| frequency (poly./bp) | 1/120 | 0 | 1/120 |

The number of nonsynonymous substitutions is shown in parenthesis.

Polymorphisms only in the coding regions were compared.

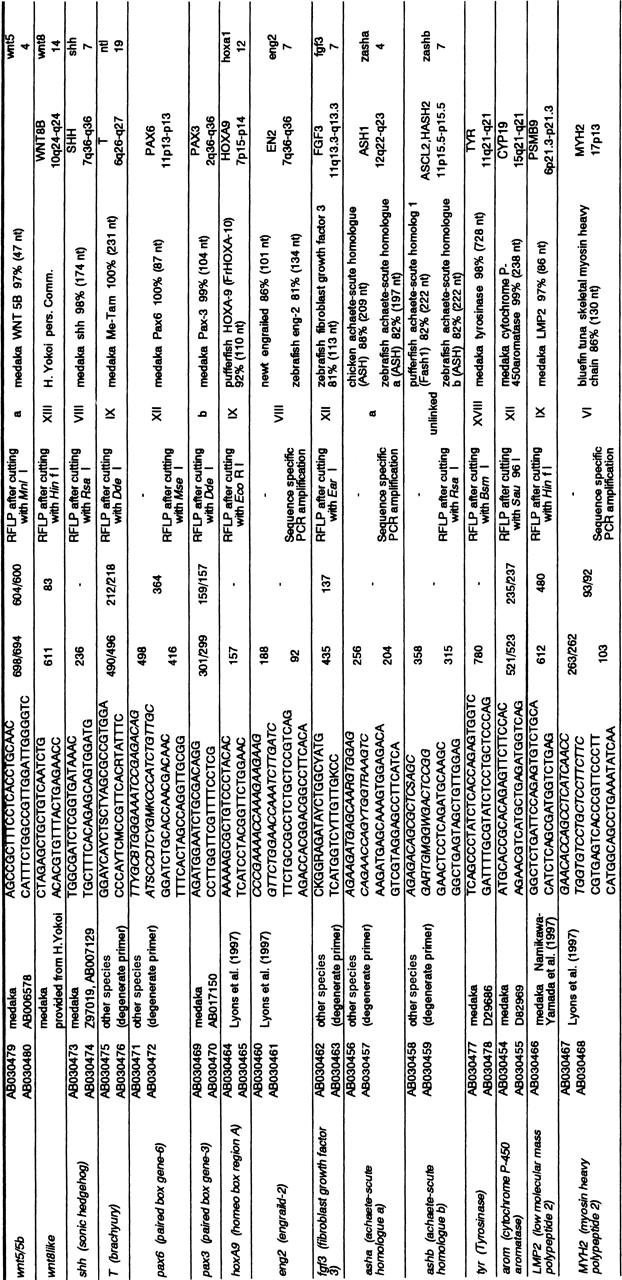

To localize 15 known genes from medaka and other species on the genetic map (Table 3), genomic fragments were amplified with PCR and determined by nucleotide sequence. All fragments showed nucleotide sequence similarity to the medaka gene (≥97%) or orthologs of genes from other species (>80%) in homology search using BLASTN. The PCR fragments amplified from nine genes were found to contain introns. All exon–intron boundaries of these nine genes followed the “GT–AG rule” for the splice donor and acceptor sites. Polymorphisms were also detected within all the introns investigated. The degree of polymorphism in the introns (one polymorphism about every 33 bp) was similar to that of anonymous STS markers described above (one polymorphism every 30 bp) (Table 2). Collectively, the degree of polymorphism in the noncoding regions including introns and anonymous STS markers was calculated to be on average one polymorphism every 31 bp. Regarding the coding regions, one polymorphism every 120 bp on average was detected (Table 2). This average is much lower than that of the noncoding regions, as expected, because expressed genes and coding regions have generally undergone selective pressure to any mutations accompanied by dysfunction. All 27 polymorphisms detected in the coding regions represented single nucleotide polymorphisms and only three (11%) gave rise to nonsynonymous substitutions. Therefore, all or most of the genes of the loci listed in Table 3 were likely to be expressed, although it was uncertain whether these genes strictly represent orthologs of genes from other species.

Table 3.

Detection of Polymorphisms in the Known Genes by PCR Amplification

| Gene | Acc. no | Primer origina | Primer pairsb | Fragment size (bp) | Intron(bp) | Polymorphism | LG | Homology c | Location in humand | Location in zebrafish (LG)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Accession numbers are shown for the medaka nucleotide sequences used for designing primer pairs.

Primer pairs depicted in italics were first primer sets used for sequencing but not for segregation analysis.

Homology search was conducted against the nucleotide sequences of the genes from the HNI strain.

The locations of the human gene loci in the human genome were taken from the homepage (http://gdbwww.gdb.org/gdb/) or were referred to in Lyons et al. (1997).

The locations of the zebrafish gene loci in the zebrafish genome were referred to Postlethwait et al. (1998).

Linkage Map

A total of 163 markers were incorporated into linkage analysis using 42 backcross progeny. Segregation ratios that departed from the Mendelian expectation of 1:1 at α-0.05 were detected at eight markers (seven of these are indicated by asterisks in Fig. 2. The remaining one has not been linked to any markers used.) This number is very close to the expected value (8.2) with a probability of 5%. Two markers showing segregation distortion were clustered on LG V.

Figure 2.

Genetic linkage map of medaka. The linkage groups on the left LGs I–XXI and LGs a–c are assigned by the female recombination-based mapping in this study. Those on the right are derived from Wada's male recombination-based map with anchoring markers. Numbers on the left of each linkage group indicate genetic distances (cM) calculated using the Kosambi mapping function. Marker names are shown at the right of each linkage group. Names of RAPD markers were given by the primer designation followed by dashes and the identification numbers of HNI-specific markers obtained with these primers. STSs were designated by the letters “sts” before the name of the original RAPD markers. The known genes and the Da locus are indicated in boldface type. The markers used for anchoring to Wada's map are boxed (white boxes are newly obtained markers in this study and shaded boxes are derived from Wada's markers). Numbering of the linkage groups was according to Wada et al. (1995). Six linkage groups (LGs a–f) could not be anchored in this study. Markers showing segregation distortion are indicated by asterisks.

One hundred forty-six markers (89.6%) of 163 analyzed were finally classified into 26 linkage groups spanning 604 cM (Fig. 2). The lengths of these linkage groups range from 0.0 to 58.5 cM. Each linkage group carries 2 to 15 markers and an average spacing of markers on this map is calculated at 5.2 ± 5.3 cM (s.d.).

To anchor our map to the previously described medaka linkage map by Wada et al. (1995), a total of 72 markers [65 markers of these were newly obtained markers in this study (Fig. 2, indicated in white boxes) and the other 7 were derived from Wada's markers (Fig. 2, indicated in shaded boxes)] were subjected to linkage analysis. As a result, 68 markers could be placed on both maps and thereby 20 of 26 linkage groups of our map could be anchored successfully to 18 linkage groups of Wada's map. LGs IX and XVI, the two separated linkage groups on our map were found to be represented by one linkage group on Wada's map (Fig. 2). Concerning LGs a–f, the anchoring markers on our map did not link to any other markers on Wada's map. Hence, these linkage groups could not be anchored in this study. The orders of the anchoring markers on Wada's map are identical with those on our map.

It is of great importance to compare between the physical and genetic distances, especially when attempting positional cloning of a mutant locus such as Da. The genetic length of the medaka genome was first estimated. Taking the distance from end markers to telomeres (250 cM; 2 telomeres × 5.2 cM × 24 chromosomes), 17 unlinked markers and 2 gaps [452 cM; (17 + 2) × 23.8 cM, maximum distance with lod score = 3 and 42 meioses] into consideration, the minimum genetic distance of the medaka genome based on female meioses was calculated at 1306 cM (604 + 250 + 452). However this value was probably underestimated because of insufficient markers to cover the whole genome. Hulbert et al. (1988) proposed the method-of-moments type estimator to estimate the genetic length from partial linkage data. Applying this method, the total map distance was calculated to be 1776 cM. According to this estimation, the marker set used in this study covers ∼74% of the entire genome and the average physical equivalent of 1 cM would correspond to 450 kb given that the entire genome size of the medaka is 800 Mb per haploid, as calculated from the data on the DNA content of the medaka genome by Uwa and Iwata (1981).

Map Position of the Da Gene

In the first linkage analysis using 42 backcross progeny, the Da gene was mapped on LG VIII. Four markers (Fig. 2; shh, eng2, stsM02-5, and stsB07-3) were found to cosegregate completely with the Da gene. This suggests that these markers are located within 8.5 cM from the Da gene with 95% confidence level. To map these markers with fine resolution and to localize them in order, additional 583 backcross progeny were used in segregation analysis around the Da gene. As a result, these markers could be placed in this order: shh and eng2 cosegregated completely with each other and were located at a 2.64-cM (1.44–4.43 cM, 95% confidence interval) distance from the Da gene; stsM02-5 was on the same side as shh and eng2 at a 0.32-cM (0.04–1.16 cM) distance from the Da gene; stsB07-3 was mapped on the opposite side of the other markers at a 0.80-cM (0.26–1.87 cM) distance from the Da gene (Fig. 3). In the Da region defined by two flanking markers, stsOPS11-1 and stsOPX06-1, recombination frequency in males was about three times higher than that in females, although molecular mechanism underlying this novel genetic feature remains to be understood (data not shown). Genomic Southern hybridization analysis using stsM02-5 as a probe, which is so far the closest marker to the Da locus, suggested that this marker represents a unique sequence in the medaka genome (data not shown). In an effort to isolate efficiently additional RAPD markers linked to the Da gene, the near isogenic line (NIL; the Da− gene was introduced from the original Da mutant with southern population background by nine generations of backcrossing in the HNI background) strain was then used. Namely, the NIL and its background HNI strains were subjected to RAPD screening. From a survey of 200 random primers, five markers were identified. However, no markers were found that localized closer to the Da gene than stsM02-5 or stsB07-3. The minimum size of the segment introduced from the original Da mutant in NIL was estimated to be 24.8 cM.

Figure 3.

Genetic linkage map around the Da locus. (A) High resolution map of LG VIII. Distances between loci are given by Kosambi centimorgans. Numbers of individuals examined are indicated in parentheses. (B) Detailed map around the Da locus. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals of genetic distances are shown in parentheses.

DISCUSSION

We constructed a medaka genetic linkage map based on female meioses. The estimated total genetic length of medaka genome was 1776 cM. Two markers closely linked to the Da gene were detected.

Detection of polymorphisms between parental strains is the first requisite to construct a genetic map. In this study, polymorphisms could be identified in all the gene fragments or STS markers investigated by PCR-based methods and incorporated into segregation analysis. This suggests that the degree of polymorphism characterizing medaka populations is high enough to be detected in a DNA fragment of a size routinely amplified by PCR. The frequency of base substitution per single nucleotide site in introns between mouse and rat was reported to be 0.201 (Hughes and Yeager 1997). These two species are thought to diverge from each other 35 ± 17 million years ago (Janke et al. 1994). Because two genetically separated populations (northern population and southern population) of medaka were estimated to branch out ∼1.5 to 2 million years ago (Sakaizumi et al. 1983), the frequency of base substitution per site in the noncoding sequences between them is expected to be 0.006 to 0.022, on the assumption that the mutation rate for base substitution in medaka was the same as that in murine rodents. In this study, one base substitution every 34 bp, which corresponds to 0.029 substitution per site, was observed. This frequency was a little bit higher than expected, which may be explained by the different rate of base substitution in medaka or earlier diversification of two medaka populations, ∼5 million years ago. When insertion/deletion polymorphism is included in addition to base substitution, one polymorphism was detected every 31 bp corresponding to 0.032 per site in the noncoding regions. If this can be extended to the entire noncoding regions in the medaka genome, a DNA fragment with 212 bp, which can be easily amplified with the PCR method, is expected to possess at least one polymorphism with the 99.9% probability. The average sizes of the introns and STS markers examined in this study were 263 and 483 bp, respectively, which should be sufficient to detect polymorphisms between the two medaka populations.

The total genetic length of the medaka genome was estimated at 1776 cM using the method described by Hulbert et al. (1988). According to this estimation, the genetic length of the medaka genome is about two-thirds that of the rainbow trout (2628 cM; Young et al. 1998) and the zebrafish (2350 cM; Knapik et al. 1998). In rainbow trout, recombination is known to occur one time per chromosome arm, because of a high degree of chiasma interference. Therefore, the genetic length can be estimated at 2600 cM (50 cM × 52 arms), which is remarkably close to the estimated length (2628 cM) of the genetic map (Young et al. 1998). The genetic length of the zebrafish genome is 2350 cM (sex-average map by Knapik et al. 1998) and the number of haploid chromosome arms is 50 (Daga et al. 1996), indicating that the average genetic length of one chromosome arm is 47 cM, although the length of some chromosome arms has been known to extend to more than 100 cM (Johnson et al. 1996). High levels of interference were also reported in medaka (Naruse and Shima 1989). The number of medaka haploid chromosome arms is 34 (Uwa and Ojima 1981). When assuming one crossover per chromosome arm, as is known to be the case for medaka, the genetic length of the medaka genome can be estimated at 1700 cM (50 cM × 34 arms). This estimation is in good agreement with 1776 cM obtained from the genetic map constructed in this study. The previous genetic map of medaka based on male meioses gave an estimated minimum length of 2480 cM (Wada et al. 1995), which is much higher than our estimation. This discrepancy is possibly due to sex or strain difference. Another possible reason is that the estimated minimum length of Wada's map may be expanded by the presence of as many as 67 unlinked markers. In Wada's map, ∼50% of markers were analyzed in only 20 backcross progeny. With such numbers, linkage can be detected with a lod score of 3.0 when markers are located within a small distance (e.g., ∼11 cM).

The phenotypes of the Da mutant are mainly observed at the trunk and tail regions with dorsoventral polarity (Ishikawa 1990; Tamiya et al. 1997). In this study, several genes such as wnt5/5b, wnt8like, shh, T, pax6, and pax3 could be positioned in the medaka genome. These genes are possibly involved in tail formation or dorsoventral patterning of neural tube or somite. However, no location of any of these candidate genes was overlapped to the Da region, indicating that these genes are not a causative gene for Da, although there is a possibility that some of these genes indirectly contribute to or modify the Da phenotypes.

Recently, evolutionary conserved chromosomal segments between human and fish have been reported (Koop and Nadeau 1996; Postlethwait et al. 1998). In medaka, the LMP2 and LMP7 gene region has been shown to constitute a syntenic group with the human corresponding region (Namikawa-Yamada et al. 1997). Our mapping study also led to the identification of four new regions of conserved synteny with several species (shh and eng2 with human and zebrafish; asha and wnt5 with zebrafish; T and LMP2 with human; fgf3 and pax6 with human; see Table 3). Among them it is of note that the shh and eng2 genes are located in the vicinity of the Da gene with a distance of 2.6 cM (1.4–4.4 cM) or 1170 kb (630–1980 kb), implying that a gene orthologous to the Da gene might be linked with these genes in human or zebrafish. In pufferfish, an average of 2 Mb is supposed to be conserved between human and pufferfish during the past 450 million years after diversification (Koop and Nadeau 1996). It is reasonable to speculate that the length of conserved linkage among fishes is much longer. In fact, our mapping study suggests that the wnt5/5b and asha gene region, which displays conserved synteny with the zebrafish corresponding region, spreads out as long as 20.7 cM, or ∼10 Mb. Therefore, it is assumed that the Da gene belongs to a conserved syntenic group, which may facilitate positional candidate gene approach for Da identification. LG 7 in zebrafish has been established to contain multiple genes such as cdh-vn, tbx6, zashb, and fgf3, which play decisive roles in embryogenesis (Postlethwait et al. 1998). As for zashb and fgf3, putative orthologous genes of medaka were mapped on different linkage groups (fgf3: LG XII, ashb: unlinked) other than LG VIII where the Da gene resides. Although these genes might join to LG VIII by further linkage mapping, the possibility of linkage disruption during evolution seems to be more plausible. The medaka orthologs of cdh-vn or tbx6 corresponding gene could be a good candidate for the Da gene because these genes are expressed in the ventral side [cdh-vn is expressed in ventral neural tube (Franklin and Sargent 1996) and tbx6 is expressed in ventral mesendoderm (Hug et al. 1997)] from the stage before morphological alteration of the Da mutant first appears. Therefore, mapping of these genes is of great importance, but medaka orthologs of these genes could not be amplified with the degenerate PCR method. Screening of a cDNA library using zebrafish gene fragments as a probe is now underway.

The distance between the Da gene and the two closest markers on either side, stsM02-5 and stsB07-3, were estimated at 0.32 cM or 144 kb and 0.80 cM or 360 kb, respectively. The resolution of our medaka map around the Da gene is 0.16 cM (−0.89 cM; 95% confidence level), which corresponds to one recombinant every 72 kb (−400 kb). This is a rough estimate as the ratio of kilobase to map unit can vary across the genome. Recombination is known to be suppressed in the centromeric regions. The distance between the Da gene and the centromere was reported to be 40 cM under complete interference condition (Naruse et al. 1988), although the centromeric region on LG VIII remains to be determined. Therefore, the Da gene was predicted to be located far from the centromere. A total of seven recombinants were obtained between stsM02-5 and stsB07-3. These individuals will be useful to determine the direction for genome walking and to minimize the critical region most likely to contain the Da gene. Taking the insert size of a BAC or PAC vector (100–200 kb) (Shizuya et al. 1992; Ioannou et al. 1994) into consideration, the distance between markers is small enough to complete the chromosome walking to the Da locus in only a few successive rounds of screening of a medaka genomic library.

METHODS

Medaka Strains and Genetic Crosses

The Japanese wild populations of medaka consist of two genetically different groups: a northern population that inhabits the northern coast of the Sea of Japan, and a southern population that inhabits the Pacific coast and the western part of the Sea of Japan coast (Sakaizumi et al. 1983). The HNI strain (Fig. 1A) is an inbred wild-type strain established from the northern population (Hyodo-Taguchi and Sakaizumi 1993). The Da mutant (Fig. 1B) was isolated from the southern population (Tomita 1975) and maintained as a closed colony (Table 4). Both populations were estimated to branch out ∼1.5 to 2 million years ago [calculated from the data of allozymic analysis by Sakaizumi et al. (1983)], indicating that a considerable degree of genetic diversity between these strains has possibly accumulated.

Table 4.

Inbred Strains and Mutant Used in this Study

| Name | Population | How to maintain | Mutant genesa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inbred strains | |||

| HNI | northern | sister × brother mating | |

| AA2 | southern | sister × brother mating | b, lf, gu |

| Hd-rR | southern | sister × brother mating | b, r |

| Mutant | |||

| Da | southern | closed colony | Da |

(b) Colorless melanophores; (r) colorless xanthophores (X-linked); (lf) leucophore-free; (gu) guanineless; (Da) Double anal fin.

A total of 625 backcross progeny were generated by crossing F1 (Da mutant × HNI strain) with the Da mutant. Five hundred forty-five progeny were obtained from F1 females and 80 were from F1 males. These progeny were reared until the phenotype could be scored. The inheritance of the Da mutant gene was assessed by observing the arrangement of dorsal melanophores and the formation of dorsal fin folds in the tail (Tamiya et al. 1997) at 2 to 3 weeks after hatching. Forty-two backcross progeny from F1 females (21 with the wild phenotype and 21 with the Da phenotype) were selected at random and used as a primary mapping population to construct the genetic map. The remaining progeny were used only to localize the Da gene in detail.

The NIL was kindly provided by Dr. Sakaizumi. The Da gene was introduced by nine generations of backcrossing (BC9) in the HNI background and BC9F1 individuals, which showed the phenotype of the Da mutant, were used as NIL. The NIL and its background HNI strains were used for RAPD screening to find markers linked to the Da gene.

RAPD Markers

RAPD analysis was conducted according to Williams et al. (1990) with some modifications. One hundred random 12 mer primers and 31 random 10–21 mer primers were used in PCR. A single primer was used in each PCR reaction. Amplification reactions were performed in total volume of 20 μl, containing 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 200 mm each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 250 nm primer, 9 ng of genomic DNA, and 0.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Syuzo Co., Kyoto, Japan). Amplification was performed in TaKaRa PCR Thermal Cycler (PJ2000 or TP3000) with the following condition: 95°C for 5 min followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 36°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min. Amplification products were subjected to electrophoresis on 1.0% agarose gels and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

All primers were individually screened against DNA from two parental strains (HNI and Da), and those that gave rise to HNI-specific bands were selected (RAPD primer sequences are available at the MEDAKAFISH HOMEPAGE; http://biol1.bio.nagoya-u.ac.jp:8000/). Segregation of these HNI-specific bands in the primary mapping population was examined.

To find polymorphic markers linked to the Da gene, 200 RAPD primers (OPQ-Z; Operon Technologies, Alameda, CA) were screened against genomic DNAs of the NIL and HNI strains, and primers that amplified HNI-specific or NIL-specific bands were selected.

STS Markers

Sixteen RAPD markers were converted to STSs (Olson et al. 1989; Table 1) by nucleotide sequence determination of PCR products generated in the RAPD analysis. RAPD bands were excised from an agarose gel and cloned into the plasmid vector, pCRII using the TA cloning kit (InVitrogen, San Diego, CA). Cloned fragments were determined for their nucleotide sequences, from which primer pairs were then designed to amplify single bands from the original RAPD loci. PCR product from each target locus was confirmed by hybridization with RAPD product and by several typical segregants. Although some STS markers obtained were amplified only from the HNI strain, to serve as sequence-specific PCR amplification markers or revealed size polymorphisms (Table 1), most were amplified from both the strains (HNI and Da) and did not exhibit any size polymorphisms. Polymorphisms of these markers were detected by cleaving with restriction enzymes or by direct sequencing of PCR products from both strains. Two primer sets that amplify the same locus were designed for stsB07-3 and stsOPS11-1. One primer set was used for segregation analysis and the other for sequencing (Table 1; shown in italics). Seven STS markers (stsB07-3, stsM02-5, stsM90-3, stsOPR04-1, stsOPS11-1, stsOPX06-2, and stsOPZ20-3) were sequenced completely from both strains, and differences in nucleotide sequences between them were identified. Regarding three STS markers (Table 1; asterisk), segregation analyses were conducted only for high resolution mapping around the Da gene.

Polymorphic Sequences Identified in Known Genes

Regarding the previously isolated genes in medaka, primer pairs were generated based on the nucleotide sequences retrieved from the DNA database. In case the information of exon–intron boundaries was available in other species such as human and mouse, primers were set on both sides outside putative exon–intron boundaries to detect polymorphisms efficiently. To obtain genomic sequences for which we had no information in medaka, the following strategy was adopted. The nucleotide sequences of other species, human, mouse, chicken, and zebrafish, were obtained from the DNA database and aligned with each other. Degenerate primers were designed within the segments, in which sequences were highly conserved among those species, also from a part of flanking introns. Some comparative anchor-tagged sequences (CATS) markers described in Lyons et al. (1997) were also used in this approach. Using these primer pairs, PCR reactions were carried out against genomic DNAs of both the parental strains. Optimization of PCR conditions was conducted according to Lyons et al. (1997) and primers that produced single PCR products were selected. These PCR-amplified products were directly sequenced using the ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequencing was performed on an Applied Biosystems model 377 DNA sequencer. Nucleotide sequences of these genes were determined from both strains. To confirm whether these products really represent the expected genes, the DNA database was searched for similar sequences using BLASTN. By comparing the nucleotide sequences between HNI and Da, RFLP sites were identified. As for genes that did not exhibit RFLP (eng2, asha, and MYH2), primer pairs were redesigned at the sites that showed single nucleotide polymorphisms from the nucleotide sequences of the HNI strain. These markers were scored as sequence-specific PCR amplification markers. Regarding pax6 and ashb, primer sets were redesigned inside the first PCR fragment because the intensity of the bands obtained was weak.

Map Construction

A whole medaka genetic map was constructed using 42 backcross progeny. Segregation of polymorphic markers was tested for 1:1 segregation ratio by performing the χ2 method. Most of linkage analyses were done with MAPMAKER/EXP 3.0 (Lander et al. 1987). Possible linkage groups were first assigned, based on the two-point analysis of markers with a lod score of at least 3.0 and a recombination fraction (υ) of at most 0.30. Preliminary orders of markers in each linkage group were established using full multipoint analysis (Lander and Green 1987) at a lod threshold of 2.0. Markers that could not be ordered with 100:1 odds were placed at their maximum likelihood positions. Potential errors were monitored using the error detection function (Lincoln and Lander 1992). When potential errors were detected, gel photos were rechecked and segregation data were corrected. Final orders of markers were confirmed with the RIPPLE command, which compares the likelihood of the original map order with that found when the order of neighboring loci is permuted. The Kosambi mapping function assumes a strong interference, which was known to be a characteristic genetic trait in medaka (Naruse and Shima 1989), was used to convert the frequencies of recombinants into map distances on the cM basis. Genome length was estimated using the formula of Hulbert et al. (1988). Only the υ value was calculated according to method 3 of Chakravarti et al. (1991). For the linkage group carrying the Da gene, a total of 625 backcross progeny were used for segregation analysis. Linkage analysis of this linkage group was conducted in the same way as described above.

Anchoring the Maps

To anchor our map to the previously described map (Wada et al. 1995), the same backcross progeny that were used to construct Wada's map were subjected to segregation analysis. The number of these progeny was 40 [20 samples were obtained by crossing F1 (AA2 female × HNI male) males with AA2 females and 20 by crossing F1 (Hd-rR female × HNI male) males with Hd-rR females; see Table 4]. Using these 40 progeny, a total of 65 markers of our map were investigated for anchoring. Linkage analysis and ordering of these markers were conducted in the same way as described above. As for six linkage groups (LGs II, IV, XI, XV, XX, and XXI), Wada's markers were localized on our map to confirm our anchoring test.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Masafumi Tanaka (Tokai Univ.) for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to Dr. Yuko Wakamatsu (Nagoya Univ.) for providing the HNI strain and the Da mutant, Dr. Naoki Shibata (Shinsyu Univ.) for the Da mutant, and Dr. Mitsuru Sakaizumi (Niigata Univ.) for providing the NIL strain. We also thank Dr. Gen Tamiya (Tokai Univ.) for helpful discussion, Dr. Hayato Yokoi (Nagoya Univ.) for providing the wnt8like primer set and Dr. Hiroshi Hori (Nagoya Univ.) for putting our information of the RAPD primer on the MEDAKAFISH HOMEPAGE. This work was supported by grants from the Yamada Science Foundation, Daiko Foundation, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) by the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, and Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for the promotion of Science for Young Scientists to M.O.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL masato@is.icc.u-tokai.ac.jp; FAX 81-463-96-2892.

REFERENCES

- Chakravarti A, Lasher LK, Reefer JE. A maximum likelihood method for estimating genome length using genetic linkage data. Genetics. 1991;128:175–182. doi: 10.1093/genetics/128.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daga RR, Thode G, Amores A. Chromosome complement, C-banding, Ag-NOR and replication banding in the zebrafish Danio rerio. Chromosome Res. 1996;4:29–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02254941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever W, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, Neuhauss SCF, Malicki J, Stemple DL, Stainier DYR, Zwartkruis F, Abdelilah S, Rangini Z, et al. A genetic screen for mutations affecting embryogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:37–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JL, Sargent TD. Ventral neural cadherin, a novel cadherin expressed in a subset of neural tissues in the zebrafish embryo. Dev Dynamics. 1996;206:121–130. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199606)206:2<121::AID-AJA1>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffter P, Granato M, Brand M, Mullins MC, Hammerschmidt M, Kane DA, Odenthal J, v. Eeden FJM, Jiang Y-J, Heisenberg C-P, et al. The identification of genes with unique and essential functions in the development of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development. 1996;123:1–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt M, Pelegri F, Mullins MC, Kane DA, v. Eeden FJM, Granato M, Brand M, Furutani-Seiki M, Haffter P, Heisenberg C-P, et al. dino and mercedes, two genes regulating dorsal development in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1996;123:95–102. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hug B, Walter V, Grunwald DJ. tbx6, a Brachyury-related gene expressed by ventral mesendodermal precursors in the zebrafish embryo. Dev Biol. 1997;183:61–73. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL, Yeager M. Comparative evolutionary rates of introns and exons in murine rodents. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:125–130. doi: 10.1007/pl00006211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert SH, Ilott TW, Legg EJ, Lincoln SE, Lander ES, Michelmore RW. Genetic analysis of the fungus, Bremia lactucae, using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Genetics. 1988;120:947–958. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.4.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt GJ, Page JRE. Linkage map of the honey bee, Apis mellifera, based on RAPD markers. Genetics. 1995;139:1371–1382. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyodo-Taguchi Y, Sakaizumi M. List of inbred strains of the medaka, Oryzias latipes, maintained in the Division of Biology, National Institute of Radiological Sciences. Fish Biol J MEDAKA. 1993;5:29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou PA, Amemiya CT, Garnes J, Kroisel PM, Shizuya H, Chen C, Batzer MA, Jong PJd. A new bacteriophage P1-derived vector for the propagation of large human DNA fragments. Nature Genet. 1994;6:84–89. doi: 10.1038/ng0194-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriki S. Preliminary note on the chromosomes of pisces: I. Aplocheilus latipes and Lebistes reticulatus. Proc Imp Acad Jpn. 1932;8:262–263. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa Y. Development of caudal structures of a morphogenetic mutant (Da) in the teleost fish, medaka (Oryzias latipes) J Morphol. 1990;205:219–232. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1052050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke A, Feldmaiier-Fuchs G, Thomas WK, v. Haeseler A, Paabo S. The marsupal mitochondrial genome and the evolution of placental mammals. Genetics. 1994;137:243–256. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.1.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Gates MA, Johnson M, Talbot WS, Horne S, Baik K, Rude S, Wong JR, Postlethwait JH. Centromere-linkage analysis and consolidation of the zebrafish genetic map. Genetics. 1996;142:1277–1288. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.4.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapik EW, Goodman A, Ekker M, Chevrette M, Delgado J, Neuhauss S, Shimoda N, Driever W, Fishman MC, Jacob HJ. A microsatellite genetic linkage map for zebrafish (Danio rerio) Nature Genet. 1998;18:338–343. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koop BF, Nadeau JH. Pufferfish and a new paradigm for comparative genome analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:1363–1365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E, Green P. Construction of multilocus genetic maps in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:2363–2367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Green P, Abrahamson J, Barlow A, Daly MJ, Lincoln SE, Newburg L. MAPMAKER: An interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics. 1987;1:174–181. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(87)90010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln SE, Lander ES. Systematic detection of errors in genetic linkage data. Genomics. 1992;14:604–610. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons LA, Laughlin TF, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Womack JE, O'Brien SJ. Comparative anchor tagged sequences (CATS) for integrative mapping of mammalian genomes. Nature Genet. 1997;15:47–56. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins MC, Hammerschmidt M, Kane DA, Odenthal J, Brand M, v. Eeden FJM, Furutani-Seiki M, Granato M, Haffter P, Heisenberg C-P, et al. Genes establishing dorsoventral pattern formation in the zebrafish embryo: The ventral specifying genes. Development. 1996;123:81–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namikawa-Yamada C, Naruse K, Wada H, Shima A, Kuroda N, Nonaka M, Sasaki M. Genetic linkage between the LMP2 and LMP7 genes in the medaka fish, a teleost. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:431–433. doi: 10.1007/s002510050298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruse K, Shima A. Linkage relationships of gene loci in the medaka, Oryzias latipes (Pisces: Oryziatidae), determined by backcross and gynogenesis. Biochem Genet. 1989;27:183–198. doi: 10.1007/BF02401800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruse K, Shimada A, Shima A. Gene-centromere mapping for 5 visible mutant loci in multiple recessive tester stock of the medaka (Oryzias latipes) Zool Sci. 1988;5:489–492. [Google Scholar]

- Olson M, Hood L, Cantor C, Botstein D. A common language for physical mapping of the human genome. Science. 1989;245:1434–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.2781285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozato K, Wakamatsu Y. Developmental genetics of medaka. Dev Growth Differ. 1994;36:437–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1994.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwait JH, Johnson SL, Midson CN, Talbot WS, Gates M, Ballinger EW, Africa D, Andrews R, Carl T, Eisen JS, et al. A genetic linkage map for the zebrafish. Science. 1994;264:699–703. doi: 10.1126/science.8171321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwait JH, Yan Y-L, Gates MA, Horne S, Amores A, Brownlie A, Donovan A, Egan ES, Force A, Gong Z, et al. Vertebrate genome evolution and the zebrafish gene map. Nature Genet. 1998;18:345–349. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RS, Williams JG, Feldmann KA, Rafalski JA, Tingey SV, Scolnik PA. Global and local genome mapping in Arabidopsis thaliana by using recombinant inbred lines and random amplified polymorphic DNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:1477–1481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaizumi M, Moriwaki K, Egami N. Allozymic variation and regional differentiation in wild populations of the fish Oryzias latipes. Copeia. 1983;2:311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Shizuya H, Birren B, Kim U-J, Mancino V, Slepak T, Tachiiri Y, Simon M. Cloning and stable maintenance of 300-kilobase-pair fragments of human DNA in Escherichia coli using an F-factor-based vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:8794–8797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamiya G, Wakamatsu Y, Ozato K. An embryological study of ventralization of dorsal structures in the tail of medaka (Oryzias latipes) Da mutants. Dev Growth Differ. 1997;39:531–538. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1997.t01-1-00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita H. On the new mutants in body color and fins of the medaka. Zool Mag. 1969;78:58. [Google Scholar]

- ————— . Mutant genes in the medaka. In: Yamamoto T, editor. Medaka (killifish), biology and strains. Tokyo, Japan: Keigaku; 1975. pp. 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- ————— The lists of the mutants and strains of the medaka, common gambusia, silver crucian carp, goldfish, and golden venus fish maintained in the Laboratory of Freshwater Fish Stocks, Nagoya University. Fish Biol J MEDAKA. 1992;4:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Uwa H, Iwata A. Karyotype and cellular DNA content of Oryzias javanicus (Oryziatidae, Pisces) Chrom Inf Serv. 1981;31:24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Uwa H, Ojima Y. Detailed and banding karyotype analyses of the medaka, Oryzias latipes in cultured cells. Proc Japan Acad. 1981;57:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Naruse K, Shimada A, Shima A. Genetic linkage map of a fish, the Japanese medaka Oryzias latipes. Mol Marine Biol Biotech. 1995;4:269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh J, McClelland M. Fingerprinting genomes using PCR with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7213–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JGK, Kubelik AR, Livak KJ, Rafalski JA, Tingey SV. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young WP, Wheeler PA, Coryell VH, Keim P, Thorgaard GH. A detailed linkage map of rainbow trout produced using doubled haploids. Genetics. 1998;148:839–850. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.2.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]