Abstract

This study traces the average net income of Canadian physicians over 150 years to determine the impact of medicare. It also compares medical income in Canada to that in the United States. Sources include academic studies, government reports, Census data, taxation statistics, and surveys. The results show that Canadian doctors enjoyed a windfall in earnings during the early years of medicare and that, after a period of adjustment, medicare enhanced physician income. Except during the windfall boom, Canadian physicians have earned less than their American counterparts. Until at least 2005, however, the medical profession was the top-earning trade in Canada relative to all other professions.

AS THE UNITED STATES STRUGGLES WITH HEALTH REFORM, Canadians observe with a mix of fascination and horror as the lies about their health care system swirl in the US media. The discussion was particularly intense in the months leading up to passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on March 23, 2010.1,2 Many of these myths have been exposed. Canadians do have free choice and good access; public administration does not add to cost, rigidity, or complexity of services, nor does it exclude private-sector involvement.3 The majority of Canadians who receive health care in the United States did not seek it deliberately; rather, they fell ill while traveling. Furthermore, their out-of-country costs are covered by the Canadian system.4 Nevertheless, the supposed faults and flaws of the Canadian system are used in US political arguments about the merits and demerits of a single-payer system.

Among the persistent myths is one about physician income and freedoms. Increasingly, US doctors are committed to the concept of coverage for all citizens.5 But some are concerned about what might be at stake for them personally. Others who oppose the changes worry about their incomes and their freedom as professionals should the president succeed with “Canadian-style,” “government-run,” single-payer health care. In speaking to the media immediately after President Obama's speech to the Joint Session of Congress in September 2009, physician–Congressman Charles Boustany of Louisiana characterized the proposals as having the potential to destroy jobs, explode the deficit, ration care, and take away “the freedom American families cherish.”6 Even proponents of health care reform think that medical income will decline.7 Indeed, evidence for better Canadian health care delivery to marginalized groups has been related to the lower fees commanded by physician services in that country. This argument relies on the idea that lower fees mean that relatively fewer tax dollars go to medical practitioners and more to services for health promotion and disease prevention.8 But fees are only tangentially indicative of earnings. For instance, Canadian physicians have lower practice expenses for a variety of reasons, including the lesser costs of billing, administration, and malpractice coverage. For both policymakers and historians, reliable information on physician net income (after expenses, before taxes) in both Canada and the United States is difficult to find. Impressionistic evidence documents disparities in earnings that typify both nations—disparities between family doctors and specialists, women and men, rural and urban practices. But it is generally acknowledged that “detailed and accurate comparative physician income studies are lacking.”9

This article addresses that information gap by tracing the long view of the average Canadian physician's net income—after expenses and before taxes—in three distinct periods: before, during, and after the advent of Canadian medicare. Sources include the Canada Census, government statistics, academic surveys, and special reports that were prepared during the advent of the current Canadian system. It will show that Canadian physicians are well paid and that medicare did not diminish their earnings. Rather medicare resulted in an initial, brief windfall of high earnings, even when compared with US data. The windfall was followed by a period of readjustment. Subsequently, Canadian medicare has maintained physicians as the top-earning professional group in that country.

A CAPSULE HISTORY OF MEDICARE IN CANADA

Taxpayer-funded medicare in Canada did not appear at a single point in time: it emerged over a quarter century from 1962, when physician services were covered across Saskatchewan, to 1987, when the demise of optional “full billing” in Ontario began. It continues to evolve in addressing new technologies and changing needs. More information about this history, with images, timelines, and links to reports and legislation can be found at the government Web site for Health Canada, the CBC Digital Archives, and the new Online Exhibition of the Canadian Museum of Civilization.10

Saskatchewan Came First, 1944–1962

Canadian medicare did not begin on a fixed date; nor was it a project of a single political party.11 The first experiment began in a single province with the Saskatchewan election of June 1944. As the Second World War dragged on, many jurisdictions in Canada had begun planning for social programs to avoid another postwar economic depression. The leader of Saskatchewan's left-leaning Cooperative Commonwealth Federation party was Tommy C. Douglas, a Baptist preacher and a gifted orator. In his youth, Douglas suffered from severe osteomyelitis; the gratis services of a kind surgeon led to his recovery. Douglas said that “no boy should have to depend either for his leg or his life upon the ability of his parents to raise enough money to bring a first-class surgeon to his bedside.”12

In 1944, Douglas and his team campaigned on a platform that promised free access to health care for all citizens. Their sweeping electoral victory made Douglas premier of what was frequently called “the first socialist government in North America.” He immediately ordered a survey on health care needs, and he invited Henry E. Sigerist, the eminent, Swiss-born physician and historian of medicine from Johns Hopkins University, to chair the health care reform. Sigerist's survey found that Saskatchewan needed exactly what Douglas had promised: government-funded hospital, medical, nursing, and physiotherapy care; physicians on salary; more clinical facilities; and a medical school.13

Hospital coverage was implemented throughout the province in 1947. A pilot project for medical care was launched in the town of Swift Current, and lengthy negotiations began with the provincial medical profession. Immensely popular, Douglas went on to win four straight elections. Eventually his team made concessions to the wary physicians, the most significant of which was fee-for-service payment for medical services rather than the proposed salary. Legislation for province-wide medical coverage was finally passed in 1962. A bitter, three-week doctors’ strike followed this new law, but the doctors lost.14 Within a year and despite their initial opposition, Saskatchewan doctors were earning more than they had in the past. One reason was that all their bills were paid and paid in full.

The Rest of Canada Came Next

While Douglas worked toward medical coverage in the 1940s and 1950s, public hospital insurance was becoming the norm in many other provinces. In 1950, 50% of Canadians had some form of private or nonprofit insurance for hospital care. A mere six years later, 99% of the population in all 10 provinces enjoyed government plans for hospital care. The following year, federal legislation, called the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act (1957),15 promised that half the costs of hospital care would be covered by the federal government. Since that time, transfers of funding from the federal government to the provinces, where the programs are administered, has provided more (or less) national leverage in health care policy.

In 1961, a national Royal Commission on Health Care Services was ordered by the Canadian Prime Minister, John Diefenbaker, the Conservative leader from Saskatchewan. The mandate was to survey all health-service needs, not only hospital care ones. It was chaired by Diefenbaker's law school classmate, the Saskatchewan judge, Emmett Hall. The Commission toured the country and met with more than 400 different groups to gather information. Hall's 1964 report recommended universal medicare for the entire country and adequate remuneration for doctors.16 An old-school Tory, Hall expected citizens to accept certain responsibilities for maintaining their health and to tolerate taxation for such a worthy cause; in exchange, the state should provide education for health professionals, as well as free doctoring and hospital coverage for its citizens. Hall was confident that the physicians and the elected officials could negotiate fees without costly third parties.16

In 1966, the Canadian Medical Care Act17 was introduced by the Liberal government of Lester Pearson and was passed almost unanimously by parliament. But health care is a provincial matter, and this legislation was federal. Once again, large transfer payments were the carrot incentive to induce provincial buy-in. Physicians were suspicious of the cumbersome system, and implementation took place slowly in the various provinces. By 1972, all 10 provinces had enacted plans for both hospital and medical services. Revisions to the plans were made in 1977, and Hall conducted another national review in 1980.

The 1984 Canada Health Act18 clarified general principles and specified terms of federal transfers. Physicians were paid—sometimes wholly, sometimes in part—from the public purse depending on their location. In Ontario for example, the province would cover 80% of the negotiated fee, and physicians were entitled to bill patients privately for the remaining 20%. Three years later, to remain eligible for the federal transfer payments, Ontario required elimination of “full billing,” which the media had successfully labeled “extra billing.” Only a minority of physicians used this symbolic remnant of discretionary fees, but most of the province's doctors went on strike over the issue. Again, the doctors lost, and some scholars suggest that public reaction to this strike cost the profession credibility and respect.19

In times of economic stress during the 1990s, federal transfer payments dwindled. Wealthier provinces, such as Alberta, took this change as a cue to allow more private services.20 Nevertheless, most jurisdictions had already implemented the medicare plans.

Medicare in the Recent Past

Canadians may complain about wait times, but health care is the country's most popular social program. Every major political party was involved in its implementation, and a publicly funded health care provision continues to be endorsed by every political party in every province. Proposing to abolish, or even alter it, is a form of political suicide. Recent reviews recommend changes within the system, rather than dismantling it.21

Notwithstanding the enthusiasm of their patients, Canadian doctors have not been universally vocal in their support of medicare; some continue to believe that their incomes would be higher with private practice. Many physicians claim that larger slices of the health care pie go to hospitals or to purchasing drugs rather than to medical services. In 2005, a successful Supreme Court challenge, launched by orthopedic surgeon Jacques Chaoulli and his patient, threatened the status quo by asserting that patient rights were infringed by wait times.22 The Canadian Medical Association (CMA) endorses medicare in principle; however, recent CMA presidents, Brian Day (2007–2008) and Robert Ouellet (2008–2009), both advocated more private practice. In 2006, Canadian Doctors for Medicare emerged in response to these trends and now boasts nearly 2000 members.

One issue that gets lost in these cross-currents is that the actual amounts of physician net earnings are unknown to the general public. Since the 1990s, information on gross earnings (or billings) and on numbers of physicians is accessible from several sources, including the Canadian Institute for Health Information and annual provincial reports, such as British Columbia's “Blue Book.”23 But these reports do not provide the expenses of practice, often between 40% and 60% of gross income; nor do they detail allowable deductions. As a result, they inflate indications of individual doctors’ earnings and may also minimize benefits.

CANADIAN MEDICAL INCOME

For this article on the history of physician income, the three periods under study were (1) before medicare, up to 1962; (2) during the advent of medicare, roughly 1962 to 1987; and (3) following the nationwide implementation of medicare, from 1987 forward.

Before Medicare

No official reports track Canadian medical income before 1900, but examples from surviving account books offer information about individual practitioners.24 By contrast, reliable statistics on wages of ordinary citizens are available. For example, from 1850 until 1880, the average wage of a laborer was roughly $300 a year with a range of $167 to about $400 (Canadian dollars of the time).25 Compared with ordinary workers, 19th-century doctors appear to have been well off (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Nevertheless, their assets were smaller than those of lawyers, and true wealth came from sources other than clinical practice. Studies of medical income in 19th-century United States suggest a similarly wide range and diversity in earnings.26

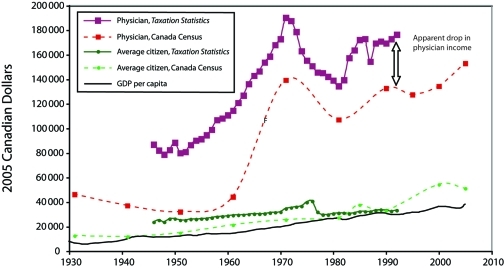

Between 1900 and 1930, most Canadian doctors enjoyed a “comfortable but not affluent income” that rose from Can $2000 to Can $6600.27 According to the Canada Census between 1931 and 1961, physicians admitted to generous incomes rising from Can $3095 to Can $6575 and ranging between two and three times national averages.28 During this period, top earners were lawyers in 1931 and 1941; doctors in 1951; and chemical engineers in 1961. The Census relies on self-reporting. Compared with government taxation sources, it seems that doctors (and others) underestimated their earnings by 15% to 60%. Consequently, the ratio of medical income to that of average earners is probably a more reliable indicator than the actual amounts. Before medicare, according to the Census, medical income was above average, but it was declining from three and a half to two times that of all Canadians by 1961 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Net income of Canadian physicians and average citizens from two sources (Canada Census and Taxation Statistics), with gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, 1930–2005.

Note. Conversion to 2005 dollars through historical Consumer Price Index, 1914–2006, Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 326–0002, http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/pick-choisir?lang=eng&searchTypeByValue=1&id=3260002 (accessed August 28, 2009). Gross domestic product per capita, reference 56.

Source. Canada Census, 1931–2006, Taxation Statistics (Ottawa, Ontario: Revenue Canada, 1948–1995).

The Advent of Medical Care, 1962–1987

The best source on net medical income through this period is the annual Taxation Statistics of the federal Department of Revenue, the so-called “green books.”29 The amounts were taken from income tax returns. They were always greater than those reported in the Census for the professions and for average earners. From 1946, physician income was specified in Taxation Statistics under “professions,” with law, dentistry, engineering, and architecture. Figure 1 shows that, according to taxation data, medical earnings rose steadily through the advent of medicare.

More information on doctors’ earnings was made available during the Hall Commission survey. The federal Department of Health and Welfare reported physician income in a special “Health Care Series” with yellow covers.30 These reports collected data back to 1957 and then tracked rising public expenditure on physician services that marked the shift from private to public payment forward to 1972. Attention was given to gender, location, and specialty, and comparisons were made with other professionals and ordinary workers. These “green” and “yellow” books show that medicare enhanced physician earnings at the outset—for example, Saskatchewan doctors saw an abrupt rise in income in the year following their 1962 strike, when the new medicare system ensured that all their bills were paid in full.

Three contradictory reasons were said to have prompted publication of the “yellow books.” First, the reports would allay medical fears and ensure that the profession was not being shortchanged. Second, the books demonstrated the greater income from group practice, a method promoted by Hall. Third, physicians suspected that the government chose to publish the books in order to manipulate public opinion by featuring their wealth.

The media loved the “yellow books” and “green books,” but doctors resented them. D. A. Geekie, communications director of the CMA, opined that they were “malicious,” seeking to “compare sheeps to goats if not alligators”; the “only reason for publishing such data,” he wrote, “is to exaggerate the gap between the average Canadian and the high earning physicians.”31 They were “inaccurate,” “inappropriate,” and morally “wrong.”32

To express these concerns in 1972, the Canadian Medical Association Journal constructed a medical metaphor. “Every fall,” it complained, “there is a short epidemic of newspaper articles … about physicians’ earnings… . The causative organism … [is] the publication of two separate but related government reports”: the “green books” and “yellow books.” “We receive a number of missiles asking why we don't put a stop to such reporting or provide an explanation to put the profession in a more favourable light.”33

The following year, medical frustration and suspicion promp- ted Geekie to construct an imaginary interview with the hypo- thetical “Dr Joe Average Canuck” and his wife, Ethel, who earns “no income but spends well … almost lavishly.” “([N]o male chauvinism intended for the 12% of the profession that is female),” wrote Geekie, but Joe “is a pretty nice guy. He works hard, is conscientious, and serves good Scotch.” Yet, Joe laments, “‘I am not nearly as well off as most people believe.’” The fictitious interviewer “suggested there had to be a limit to what Canada could pay physicians.” Then the phone rang, and Doc Canuck rushed off to an emergency, although he was not on call.34

Sympathy for the doctors’ plight can be found in the graph of percentage change in net earnings through this same period (Figure B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). With periodic controls set on their fees and no protection from inflation of expenses, a yo-yo effect of chaotic swings for the percentage of change of physician earnings contrasts starkly with the slow steady rise for average Canadians exemplified by employees and laborers. The supposedly reassuring numbers were alarming. Physician resentment over the “yellow books” ended with the books’ demise in 1973. This quiet execution coincided with the first year since 1957 that the percentage of change of medical income actually fell below that of average Canadians. For once, the government may also have found the report embarrassing.

Notwithstanding the marked drop in the percentage of change of earnings for 1972, medical income had peaked at an all-time high in the preceding year (Figure 1). Henceforth, analysts would refer to this rise as the “windfall” of early medicare, which ended after the 1971–1972 peak year.35 In his annual rant of 1975, Geekie described a dramatic reversal in “pecking order of the various professional groups,” referring to yet another decline in the percentage of change of medical earnings, although actual income amounts continued to rise.36 This “period of adjustment” set the stage for a future climate of mistrust.37

The 1970s was a decade of tension. Physicians continued to be the top earners, but their net incomes rose at a rate that was less than in the recent past, less than inflation, and less than those of other professions.38 The result was a steady decline in medical income relative to average earners over a decade until about 1981, although earnings never dipped as low as they had been before medicare (Figure 1). To control costs, some policy analysts recommended closing immigration to foreign graduates and ending the fee-for-service system in favor of salaries.39 Many anxious reports and editorials appeared; doctors threatened to move to the United States. Medicare was said to have taken a toll on physician morale, professional satisfaction, and financial status.40 Some surveys aired in American media to emphasize the “dissatisfaction,” “bitterness,” and thoughts of leaving among Canadian doctors victimized by government interference.41

By 1980, an economist recommended what Hall had opposed: that fee schedules be reviewed regularly by a third party.42 This plan was never implemented. Fees are still negotiated by professional associations and governments without third-party mediators.

Notwithstanding the temporarily reduced rate of change in their earnings, physicians constituted the top-earning profession in Canada every year from 1958 forward and into the present. Their average net income increased at a rate that consistently outstripped that of all citizens: 1200% versus 676% over 4 decades. The ratio of physician income to that of all Canadians was higher than before medicare, ranging between three and five-and-a-half times with an overall upward trend. Sometimes the percentage of increase was less than that of other professions, but actual earnings remained greater. The gap between physicians and the next-highest income group peaked in the early 1970s “windfall” moment, readjusted in the mid-1970s, and then steadily widened again in favor of physicians. The relative drop during the decade of 1971 to 1981 exemplifies the profession–government tension in that time of anti-inflation measures and fixed fees—tensions that pervaded the media and the popular, uncontrolled surveys cited previously.

The “green book” figures were slightly higher than were those in the “yellow books” because Taxation Statistics included income sources other than practice, such as securities and real estate; in some years, salaried doctors were excluded. Doctors argued that the “green books” gave a falsely high impression of their earnings and blurred distinctions between general practitioners versus specialists, rural versus urban, male versus female, and salaried versus private. After 1992, Taxation Statistics information on medical earnings dried up, owing to revisions in income tax law that relieved taxpayers of the obligation to specify their occupations.

Late 1980s to 2005

For the most recent decades, the best source on net medical income remains the Canada Census.43 Once again, the data are self-reported and probably underestimated. Turning from the more reliable Taxation Statistics to sole reliance on the Census source generates an apparent, abrupt drop in medical income between 1992 and 1995 (Figure 1). According to the Census, however, the trend in income continued upward with no drop, seemingly at the same rate as before 1992. Therefore, the “drop” between 1992 and 1995 may be an artifact of the Census source and the underreporting that characterizes it for all citizens.

From 1992 to 1995, the Medical Post reinstigated its satisfaction surveys, and the CMA conducted a similar study in 1997.44 But these polls provided no details on income because such questions were not asked.

COMPARISON WITH US PHYSICIANS

Finding reliable historical information about medical earnings in the United States is even more difficult than it is for Canada. Like their northern colleagues, US physicians have not been forthcoming about their earnings, except when it comes to protesting inflated estimates. As early as 1897, an American doctor suggested that rich doctors were charlatans.45 In 1911, a remark that medics earned “princely sums” drew a sharp rebuke.46 In 1989, a physician wondered about the uncaring message of ostentation sent by the luxury cars belonging to his colleagues.47 Most articles on physician earnings in the American peer-reviewed literature address concerns about income of particular medical groups identified by specialty, location, or other characteristics, such as radiologists, neurologists, surgeons, women, and academics.

Without a single-payer system, Americans must rely on volunteer surveys conducted by the profession, scholars, government, or the media. But surveys are vulnerable to the criticisms of definition, response rate, honesty, and variable motivation: those with perceived complaints respond more reliably. And, just as in Canada, disparities emerge involving gender, race, location, and specialty, and between reported versus actual income.

American sources for this research included a survey on physician income undertaken by the Committee of Costs on Medical Care just before the stock market crash of 1929,48 a government study from 1945 to 1966,49 and sporadic surveys conducted by academics,50 by the journal Medical Economics from 1948 to 2003,51 and by the American Medical Association in 1928,52 1949 to 1950,53 and from 1988 to 200354 (Figure C, available as a supplement to the online version of the article at http://www.ajph.org). Median incomes, if given, were lower than average incomes, but not all surveys provided both figures.

The data points shown in the supplemental figure were consolidated. If two different incomes were reported when these surveys occasionally coincided, an average was taken. Converting Canadian medical incomes (as shown in Figure 1) to historical equivalent US dollars and converting both American and Canadian figures to 2005 US dollars allows comparison of medical earnings in the two countries across 8 decades (Figure 2).55

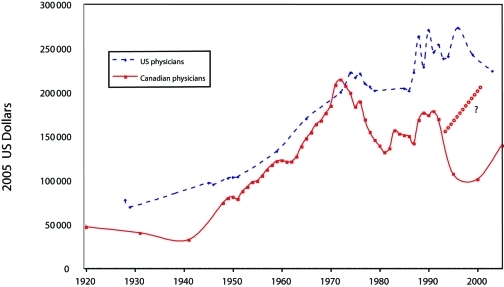

FIGURE 2.

Physician income in Canada and the United States, 1920–2005.

Source. For Canadian physician income, see Canada Census, 1931–2006 and Taxation Statistics (Ottawa, Ontario: Revenue Canada, 1948–1995). 24,28 For US physician income, see references 48-54.

aExtrapolation of Canadian physician income based on Taxation Statistics.

Figure 2 shows that US physicians have almost always earned more than Canadian physicians. The gap closed at the advent of medicare during the 1960s and early 1970s, when Canadian doctor income soared to equal and even exceed that of American doctors. Then the gap widened again; however, the mid-1990s disparity may be apparent, owing to the Canada Census source for the years after 1992. The latest figures suggest a renewed trend to narrow the gap with a relative decline in US physician earnings while the Canadian equivalent continues to rise.

But these differences in income may be common to all Canadian and US earners, not only physicians. The historical gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in each country reflects average earnings of all citizens. Canadian GDP per capita is close to the income of the average worker (Figure 1). It has never equaled that of the United States, ranging from a high of 91.4% in 1904 to a low of 60.3% in 1934 with other peaks in the late 1960s and early 1970s.56

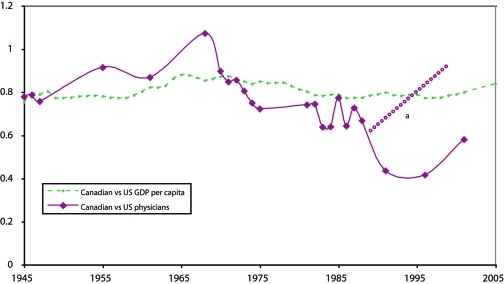

Through time, the ratio of Canadian to US physician earnings, as shown in Figure 2, has ranged from 0.4 to 1.1. Figure 3 compares this ratio of physician income in the two countries to the ratio of the GDP per capita between the two countries for the same period. It appears that, in the early years of medicare—roughly 1962 to 1970—Canadian doctors fared at least as well or better than their country as a whole relative to the United States. Then, as medicare became established, Canadian physicians fared less well. Once again, however, the wider gap after the mid-1990s could be attributable to the Census source that suggests a falsely lower medical income.

FIGURE 3.

Ratio of Canadian gross domestic product (GDP) per capita to US GDP per capita and ratio of Canadian physician income to US physician income, 1945–2005.

Source. For Canadian physician income, see Canada Census, 1931–2006 and Taxation Statistics (Ottawa, Ontario: Revenue Canada, 1948–1995).24,28 For US physician income, see references 48-54. For gross domestic product per capita in both countries, see reference 56.

aExtrapolation of Canadian physician income based on Taxation Statistics.

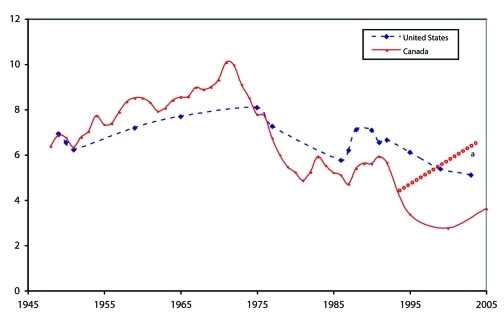

However, it is perhaps more meaningful to compare physician incomes to the GDP per capita within each country—i.e., Canadian physicians to Canadian citizens, and US physicians to US citizens—something the Canadian government had been trying to do with “yellow books” of the 1960s and early 1970s (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Ratio of Canadian physician income to Canadian gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and ratio of US physician income to US GDP per capita, 1945–2005.

Source. For Canadian physician income, see Canada Census, 1931–2006 and Taxation Statistics (Ottawa, Ontario: Revenue Canada, 1948–1995).24,28 For US physician income, see references 48-54. For gross domestic product per capita in both countries, see reference 56.

aExtrapolation of Canadian physician income based on Taxation Statistics.

Figure 4 shows that the ratio of physician earnings to the GDP per capita in their own countries has been high, ranging from roughly 3 to 10 times. Surprisingly, the greatest ratio was Canadian, not American, from roughly 1962 to 1972, when physician earnings reached 10 times the GDP per capita of that nation during the “windfall” years of early medicare. Indeed, Canadian physicians also seem to have experienced the lowest ratios in the 1980s and mid-1990s. Since then, the Canadian ratio has been increasing, although it remains smaller than its American equivalent. But, again, Canadian values from the mid-1990s may be falsely low owing to the use of the Census source in the absence of disaggregated tax data.

Overall, Figure 4 shows that the US ratio has usually been higher than the Canadian ratio, and its range narrower, from just above five to just over eight times the GDP per capita in that country; the trend may be declining since the mid-1990s. In 2005, US doctors earned about five-and-a-half times the US GDP per capita; Canadian doctors earned about four times their country's GDP per capita. These estimates are backed by a recent international study of physician supply.57

SUMMARY

To summarize these results, Canadian doctors were always well paid. Before 1900, they were comfortable, but they drew on many income sources and carried large debts. The advent of medicare resulted in a temporary boom that raised expectations and provoked a funding crisis. Following the 1971–1972 peak in medical earnings, controls—on fees, wages, and prices—set the thermostat for reactions between the profession and government. Annual percentage changes in medical income were sometimes negative or less than inflation for several years. This situation fostered insecurity and a lingering physician mistrust of government. However, the years after 1981 saw a steady rise in medical income. Data for physician income after 1992 may be falsely low owing to the Census source. Changes promised to the Canada Census in 2010 imply that its accuracy could decline further in the future, and information on health and income data will be even more difficult to obtain.58 Nevertheless, the trends revealed in this research are reliable. Over nearly 60 years, into the 21st century, physician income grew at a rate of increase that outpaced that of other Canadians. Since 1958 through the advent of medicare, until at least 1992 and probably into the present, physicians, as a professional category, were the top earners in the country.

Compared with the best figures available for US physicians, Canadian doctors have almost always earned less. However a comparison of medical earnings to the GDP per capita in each country shows that Canadian physicians earned proportionately most in the early years of medicare, peaking around 1972 when amounts equaled and briefly exceeded US medical income. Their earnings then returned to three or four times that of the GDP per capita, a level that is nonetheless greater than it had been before medicare, and that is still rising. An analogy can be found here with the apparent boom in US medical income associated with the advent of US Medicare in 1966.59

The observation that Canadian physicians are paid less than their American counterparts invites us to ask, what do Canadians “get” in exchange for paying their physicians less than their American counterparts? A 1990 study showed that, although per capita expenditures on health in the United States were higher than those in Canada, the actual number of services was fewer.60 In other words, Canadian citizens were getting more and spending less. Perhaps the corollary of this observation is that Canadian doctors suffer because they work more for less. Other comparisons suggest that the high costs of American care are not owing to the admittedly higher physician fees and income, but rather to the much greater costs of administration generated by the private insurance industry.61

In Canada, proportionately more resources are devoted to public health and to providing free access to all citizens through a system that costs less than its American counterpart and is associated with longer lifespan and lower infant mortality. In other words, better health indicators and greater accessibility are correlated with the lower physician income.

Is it possible that high physician income could be correlated with lower health outcomes? The health indicators of Cuba, for one extreme example, are among the best in the world for a developing nation; yet, physicians in that country—the vast majority of whom are in general practice—are known to exist on derisory salaries amounting to less than US $600 a year.62 Anthropological researchers characterize the health of the country as a “gift,” provided by the collective, including its doctors.63

Using the gift analogy then, Canada's doctors, who often pay lip service to “advocacy,” “accountability,” and “teamwork,” can be seen to make an investment in public health stemming from their lower earnings relative to American doctors. But we have no idea what the contribution has been costing them in recent years—if anything—because we cannot obtain the figures.

No one is proposing to cut physician incomes to the insignificant amounts of Cuba. Yet how much money do doctors really need? A few scholars have used a variety of economic theories to analyze physician income. By whatever model they chose to define the task, the amounts paid in Canada and the United States were said to be too great.64 In other words, whether or not it correlates with lower health indicators, high medical income could be a moral problem.

OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

From this research, we observe that even when the readjustments resulting from various policy and payment alterations are taken into account, Canadian medicare did not lead to a loss in physician income. Rather, physician in-comes grew more quickly than those of other Canadians and are considerably greater. In short, the medical-income argument against moving toward a Canadian-style system is feeble. The only way to revive it would be to find different and more reliable data.

Therefore, a recommendation arising from this work is to make more data on physician income available. The information for this research was not easily gathered; better figures may reside in sources currently inaccessible to the average practitioner or historian. Distinctions between specialties, race, gender, and geographic location would emerge.

This information problem raises several questions relevant to both countries. Why should medical income be secret? Are physicians embarrassed by their wealth? Someone has to be the top earner. What is wrong with that person being a doctor instead of a hockey player? Even more puzzling—if not ironic—is the effect of Canadian legislation, such as the Ontario Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act (1996), which ensures that the actual names and actual incomes of citizens paid more than Can $100 000 from the public purse are published every year in the so-called “sunshine lists” at government Web sites and in leading newspapers.65 This move to greater accountability makes an annual spectacle of the wages of teachers, professors, police officers, hospital administrators, and government employees—anyone paid by tax dollars. Journalists and voyeuristic citizens use the lists to scrutinize individual and collective use of resources.66 But doctors’ names do not appear in these famous lists unless they enjoy public-sector salaries, such as stipends for academic or hospital administration. Yet, they are paid by the taxpayer whether their earnings derive from salaries or from fee billings; transparency and accountability dictate that taxpayers have a right to know how all their money is spent.

Therefore, physicians should join citizens in encouraging the revival of those annual “green” and “yellow” reports, or their equivalents. Doctors might be pleasantly surprised to discover that patients believe that they are entitled to high incomes because of their many years of expensive study, heavy responsibilities, and long hours of work. In turn, citizens might have reason to take pride in remunerating hardworking physicians at a level that is decent without being obscene.

The universal, single-payer system has been good not only for Canadians but also for their doctors. At least, it has done no harm.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Irfan Dhalla of the University of Toronto; Phil Giles and Rejean Lasnier of Statistics Canada; Jeff Moon of the Queen's University Documents Library; David Elder, Duncan G. Sinclair, Arthur Sweetman, and Robert D. Wolfe of Queen's University School of Policy Studies; David M. C. Walker, former Dean of Queen's University Faculty of Health Sciences; and Theodore Brown, Elizabeth Fee, and two anonymous reviewers for the journal.

Endnotes

- 1.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148, 111th Congress, 23 March 2010, HR 3590

- 2.S.G. Stolberg, R. Pear, “Obama signed health care overhaul bill with a flourish,” New York Times, 23 March 2010, A19

- 3.See, for example, P. Armstrong, H. Armstrong, C. Fegan, Universal Health Care: What the United States Can Learn From Canada (New York, NY: The New Press, 1998); Bruce Campbell and Greg Marchildon, ed., Medicare: Facts, Myths, Problems, Promise (Toronto, Ontario: Lorimer, 2007); Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, “Myth: In Health Care, More is Always Better,” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 14 (2009):124–125; Steffie Woolhandler, Terry Campbell, and David U. Himmelstein, “Costs of Health Care Administration in the United States and Canada,” New England Journal of Medicine 349 (2003): 768–775; Joseph S. Ross and Allan S. Detsky, “Comparison of the US and Canadian Health Care Systems: A Tale of 2 Mount Sinais,”Journal of the American Medical Association 300 (2008): 1934–936; Raisa Berlin Deber, “Health Care Reform: Lessons From Canada,” American Journal of Public Health 93, no. 1 (2003): 20–24

- 4.Steven J. Katz, Karen Cardiff, Marina Pascali, Morris L. Barer, and Robert G. Evans, “Phantoms in the Snow: Canadians’ Use of Health Care Service in the United States,” Health Affairs (Millwood) 21, no. 3 (2002):19–31 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.A.E. Carroll and R.T. Ackerman, “Support for National Health Insurance Among U.S. Physicians: 5 Years Later,” Annals of Internal Medicine 148, no. 7 (2008):566–567 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Web site for Charles W. Boustany Jr, MD, Speech given September, 2009, http://boustany.house.gov/index.html (accessed August 27, 2010)

- 7.Scott Gottlieb, “How ObamaCare Will Affect Your Doctor,” Wall Street Journal, May 12, 2009, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124208383695408513.html (accessed November 17, 2010)

- 8.S.J. Katz, S. Zuckerman, and W.P. Welch. “Comparing Physician Fee Schedules in Canada and the United States,” Health Care Financing Review 14 (1992):141–149; S.E.D. Shortt, The Doctor Dilemma: Public Policy and the Changing Role of Physicians Under Ontario Medicare (Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999); W.P. Welch, S.J. Katz, and S. Zuckerman, “Physician Fee Levels: Medicare Versus Canada,” Health Care Financing Review 14, no. 3 (1993):41–54

- 9.Ross and Detsky, “Comparison,” 1936

- 10.Health Canada, “Canada’s Health Care System (Medicare),” http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/medi-assur/index-eng.php (accessed November 17, 2010); CBC Digital Archives, “Health Care System,” http://archives.cbc.ca/health/health_care_system/topics/90/ (accessed November 17, 2010); Canadian Museum of Civilization, “Making Medicine: The History of Health Care in Canada, 1914 to 2007, Online Exhibition,” http://www.civilisations.ca/cmc/exhibitions/hist/medicare/medic-credits_e.shtml (accessed November 17, 2010)

- 11.C. David Naylor, Private Practice, Public Payment: Canadian Medicine and the Politics of Health Insurance, 1911–1966 (Montreal, Quebec, and Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986); Aleck Ostry, Change and Continuity in Canada’s Health Care System (Ottawa, Ontario: CHA Press, 2006); Malcolm G. Taylor, Health Insurance and Canadian Public Policy: The Seven Decisions That Created the Canadian Health Insurance System and Their Outcome, 2nd ed. (Montreal, Quebec, and Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1987); C. Stuart Houston, Steps on the Road to Medicare: Why Saskatchewan Led the Way (Montreal, Quebec, and Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002); C. Stuart Houston and Bill Waiser, Tommy’s Team: The People Behind the Douglas Years (Calgary, Alberta: Fifth House, 2010)

- 12.Lewis H. Thomas, The Making of a Socialist: The Recollections of T.C. Douglas (Edmonton, Alberta: The University of Alberta Press, 1982): 7

- 13.Jacalyn Duffin and Leslie Falk, “Sigerist in Saskatchewan: The Quest for Balance in Social and Technical Medicine,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 70 (1996): 658–683; Jacalyn Duffin, “The Guru and the Godfather: Henry E. Sigerist, Hugh Maclean and the Politics of Health Care Reform in 1940s Canada,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 9, no. 2 (1992): 191–218 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Robin F. Badgley and Samuel Wolfe, Doctors’ Strike: Medical Care and Conflict in Saskatchewan (Toronto, Ontario: Macmillan, 1967)

- 15.Government of Canada, Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act, Statutes of Canada, 5–6 Elizabeth II (c 28, S1 1957), 1957

- 16.Canada Royal Commission on Health Services Report (Ottawa, Ontario: Queen’s Printer, 1964–1965): 541–544

- 17.Government of Canada, Medical Care Act, Statutes of Canada (c 64, s 1), 1966–1967

- 18.Government of Canada, Canada Health Act, Bill C-3, Statutes of Canada, 32–33 Elizabeth II (RSC 1985, c 6; RSC 1989, c C-6), 1984, http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/c-6/index.html (accessed March 21, 2011)

- 19.E. Meslin, “The Moral Costs of the Ontario Physicians’ Strike,” The Hastings Center Report 17 (1987): 11–14 [PubMed]

- 20.Pat Armstrong and Hugh Armstrong, Wasting Away: The Undermining of Canadian Health Care (Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press, 2003): 56–58, 168–172; Carolyn Hughes Tuohy, “Canada: Health Care Reform in Comparative Perspective,” in Comparative Studies and the Politics of Modern Medical Care, ed. Theodore R. Marmor, Richard Freeman, and Kieke G.H. Okma (New Haven, CT, and London, England: Yale University Press, 2009): 61–87

- 21.R. Romanow, Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, 2002);Michael Kirby, Reforming Health Protection and Promotion in Canada: Time to Act (Ottawa, Ontario: Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, 2003)

- 22.R. Ouellet, “The Chaoulli Decision: A Debate in Which Physicians Must Be Heard,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 173, no. 8 (2005): 896; Marie-Claude Prémont, “Wait-Time Guarantees for Health Services: An Analysis of Quebec’s Reaction to the Chaoulli Supreme Court Decision,” Health Law Journal 15 (2007):43–56

- 23.Canadian Institute for Health Information, Health Spending Databases, National Physician Database, http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=hhrdata_npdb_e (accessed November 17, 2010); British Columbia, Ministry of Health Services, Medical Services Commission, Financial Statement, “Blue Book,” http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/msp/financial_statement.html (accessed November 17, 2010). In the 2009 statement, approximately 8800 individual physicians billed roughly Can $3 billion, or approximately Can $340 000 each

- 24.S.E.D. Shortt, “Before the Age of Miracles: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of General Practice in Canada, 1890-1940,” in Health, Disease and Medicine: Essays in Canadian History, ed. Charles G. Roland (Toronto, Ontario: Hannah Institute, 1984): 123–152; Charles G. Roland and B. Rubeshewsky, “The Economic Status of the Practice of Dr. Harmaunus Smith in Wentworth County, 1827-67,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 5 (1988): 29–49; Jacalyn Duffin, Langstaff: A Nineteenth-Century Medical Life (Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 46–58; Robert D. Gidney and Wynn P.J. Millar, Professional Gentlemen: The Professions in Nineteenth-Century Ontario (Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 1994): 39–40, 189–195, 403–405

- 25.Malcolm C. Urquhart, Historical Statistics of Canada (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1965); F.H. Leacy, Historical Statistics of Canada, 2nd ed. (Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada, 1982)

- 26.J. Coombs, “Rural Medical Practice in the 1880s: A View From Central Wisconsin,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 64, no. 1 (1990): 35–62; E. Brooks Holifield, “The Wealth of Nineteenth-Century American Physicians,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 64, no. 1 (1990): 79–85 [PubMed]

- 27.Shortt, “Before the Age of Miracles,” 135–136

- 28.Noah M. Meltz, Manpower in Canada, 1931–1961: Historical Statistics of the Labour Force (Ottawa, Ontario: Department of Manpower and Immigration, Program Development Service, Research Branch, 1969). See also Survey of Physicians in Canada, ed. J. Willard (Ottawa, Ontario: Department of National Health and Welfare, Research and Statistics Division, series 1946–1955)

- 27.Taxation Statistics (Ottawa, Ontario: Revenue Canada, 1948–1995)

- 30.Earnings of Physicians in Canada, Health Care Series, 1957–1970 (Ottawa, Ontario: Department of National Health and Welfare, Research and Statistics Directorate, 1963–1972)

- 31.D.A. Geekie, “Canadian Government Figures Show Near-Halt in 1971–72; Physicians’ Income Change,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 113, no. 10 (1975): 1002–1005 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.D.A. Geekie, Letter, “MD Incomes 1961–67,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 110, no. 7 (1974): 755 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.[No authors listed], “Earnings of Canadian Physicians, 1959–69,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 106, no. 6 (1972):719–721 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.D.A. Geekie, “MD Incomes, 1961–1971,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 109 (1973): 1246, 1249–1250, 1252, 1260 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.R.D. Fraser, Physician Incomes in Canada (Kingston, Ontario: Queen’s University, 1980): 9; Robert G. Evans, Strained Mercy: The Economics of Canadian Health Care (Toronto, Ontario: Butterworths, 1984): 15–16; Robert G. Evans and Morris L. Barer, “Riding North on a South-Bound Horse? Expenditures, Prices, Utilization and Incomes in the Canadian Health Care System,” in Medicare at Maturity: Achievements, Lessons and Challenges, ed. Robert G. Evans and Greg L. Stoddart (Calgary, Alberta: The Banff Centre for Continuing Education, 1986): 53–163, esp. 92

- 36.Geekie, “Canadian Government Figures,” 1002 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Jane M. Fulton, Canada’s Health Care System: Bordering on the Possible (Washington, DC: Falkner and Gray, 1993): 69–70

- 38.Shortt, Doctor Dilemma, 30

- 39.S. Wolfe and R.F. Badgley, “How Much is Enough? The Payment of Doctors—Implications for Health Policy in Canada,” International Journal of Health Services 4, no. 2 (1974): 245–264 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Walter C. Mackenzie, “Medicare: The Cost to the Medical Profession [editorial],” Canadian Medical Association Journal 119, no. 9 (1978): 995 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Anon, “Canada’s MDs Embittered by Health Plan,” Medical World News 20, no. 3 (1979): 23; Anon, “Canadian Survey Reveals Widespread Dissatisfaction Among Physicians, American Medical News 22, no. 6 (1979): 17–19 [PubMed]

- 42.Fraser, Physician Incomes in Canada, 45

- 43.Canada Census 1991, 1996, 2001, 2006, “Employment Income of Physicians,” for 1990 and 1995, extracted from Statistics Canada, Table CD Series Dimensions 94F0005XCB; for 2000 and 2005 extracted from Statistics Canada, Schedule 8, Employment Income Statistics (Cat.97-563-X2006-0063), http://www.statcan.gc.ca (accessed August 28, 2009)

- 44.Taking the Pulse: The CMA Physician Resource Survey (Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Medical Association, 1997)

- 45.Anon, “Professional Incomes [editorial],” Journal of the American Medical Association 28 (1897): 1037–1038

- 46.F.E. Wallace, “Incomes of Physicians,” Journal of the American Medical Association 56 (1911): 835; H.W. Wiley, “Incomes of Physicians [letter],” Journal of the American Medical Association 56 (1911): 835

- 47.D.B. Cauthen, Letter, “Luxurious Cars: Should Physicians Flaunt their Wealth?” Journal of the American Medical Association 262, no. 12 (1989):1631 [PubMed]

- 48.M. Leven, The Incomes of Physicians: An Economical and Statistical Analysis (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1932)

- 49.L.S. Reed, Studies of the Incomes of Physicians and Dentists (Washington, DC: Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Social Security Administration, 1968)

- 50.Michael C. Thornhill, “Physician Income: Historic and Recent Changes in Payment Sources, Income Levels, and Professional Autonomy,” in The Business of Medicine, ed. G. Gitnick, F. Rothenberg, and J.L. Weiner (New York, NY: Elsevier, 1991): 7–18; Ha T. Tu and Paul B. Ginsburg, Tracking Report. Losing Ground: Physician Income 1995–2003 (Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change, 2006), http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/851/ (accessed November 17, 2010)

- 51.W.A. Richardson, “Physicians’ Income,” Medical Economics 25, no. 12 (Sep 1948): 59; 26 (Oct 1948): 63; 26 (Nov 1948): 59; 26 (June 1949): 63; Arthur Owens, “Doctors’ Earnings: Inflation Edges Ahead,” Medical Economics 55, no. 19 (Sep 1978): 226–231, 234–235, 241–242; Arthur Owens, “Doctors’ Earnings: Look What’s Happening to Your Buying Power,” Medical Economics 56, no. 19 (Sep 1979):190–194, 196–202; Arthur Owens, “Earnings: Have They Flattened Out for Good? Medical Economics 63, no. 18 (Sep 1986): 162–181; Arthur Owens, “How Much Did Your Earnings Grow Last Year?” Medical Economics 65, no. 17 (Sep 1988): 159–163, 166–168, 170; Arthur Owens, “Earnings: Are You One of Those Losing Ground?” Medical Economics 66, no. 17 (1989):130–137, 141–142, 147–148; Arthur Owens, “Earnings Make a Huge Breakthrough,” Medical Economics 67, no. 17 (Sep 1990): 90–94, 104–105, 108; H.D. Larkin, “High Incomes, Low Costs: How Do They Do It?” Medical Economics 75, no. 17 (Sep 1998): 92–94, 97–100, 106; J.H. Goldberg, “Doctor’s Incomes: Who’s Up, Who’s Down?” Medical Economics 75, no. 17 (Sep 1998): 166–168, 171–177, 181–182; J.H. Goldberg, “Doctor’s Earnings Make a Stride,” Medical Economics 76, no. 18 (Sep 1999):172–175, 178, 183–186; L.W. Ghormley, “I Was Wrong. Medicare Is Great!” Medical Economics 79, no. 9 (May 2002):71–72, 77; Robert Lowes, “Earnings. Primary Care Tries to Hang on,” Medical Economics 81, no. 18 (Sep 2004): 52–54, 56, 58; Wayne J. Guglielmo, “Physicians’ Earnings: Our Exclusive Survey,” Medical Economics 80, no. 18 (Sep 2004): 71–72, 76–79; Charlotte L. Rosenberg, “Goodbye Charity Clinics: Fee for Service Is Moving in,” Medical Economics 51, no. 20 (1974): 145. See also Milan Korcok, “US Physicians’ Earnings. Part I: They Spend More but Still Keep More,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 120, no. 2 (1979):187–189

- 52.R.G. Leland, “Income from Medical Practice,” Journal of the American Medical Association 96 (1931): 1683–1691

- 53.Marcus S. Goldstein, “Medical Group Practice in the United States,” Journal of the American Medical Association 142 (1950): 1049–1052; Frank G. Dickinson and Charles E. Bradley, “Survey of Physicians’ Incomes,” Journal of the American Medical Association 146 (1951): 1249–255; Anon., “Sample of 1951 Physicians’ Incomes,” Journal of the American Medical Association 149, no. 2 (1952): 149–167

- 54.Martin L. Gonzalez et al., Physician Marketplace Statistics (Chicago, IL: AMA Center for Health Policy Research, 1988–1998);John D. Wasenaar and Sara L. Thran, Physician Socioeconomic Statistics, 2000–2002 edition (Chicago, IL: AMA Center for Health Policy Research, 2003)

- 55.For historical exchange rate of Canadian dollars to US dollars, see “Pacific Exchange Rate Service” of Sauder School of Business, University of British Columbia, at http://fx.sauder.ubc.ca/etc/USDpages.pdf (accessed November 17, 2010)

- 56.A. Maddison, The World Economy: A Millenial Perspective (Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2001); Angus Maddison, The World Economy: Historical Statistics (Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2003); Jean-Pierre Maynard, A Comparison of GDP per Capita in Canada and the United States From 1994 to 2005 (Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada, 2007); Factbook 2009: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics: Macroeconomic Trends – Gross Domestic Product (GDP) - Size of GDP (Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2009)

- 57.Richard M. Scheffler, Is There a Doctor in the House? Market Signals and Tomorrow’s Supply of Doctors (Stanford, CA: Stanford General Books, 2008): 73

- 58.R. Collier “Long-Form Census Change Worries Health Researchers,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, News, July 22, 2010, http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/rapidpdf/cmaj.109-3322v1 (accessed November 17, 2010).Anon., Editorial: “Save the Census: The Canadian Government Should Rethink Its Decision to Change the Way Census Data Are Collected,” Nature 466, no. 7310 (2010): 1043

- 59.J. Holahan, J. Hadley, W. Scanlon, R. Lee, and J. Bluck, “Paying for Physician Services Under Medicare and Medicaid,” Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 57, no. 2 (1979): 183–211, esp. 191–192; John Holahan and William Scanlon, Price Controls, Physician Fees, and Physician Incomes From Medicare and Medicaid (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, 1978); Theodore R. Marmor, The Politics of Medicare, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter, 2000): 84, 98

- 60.V.R. Fuchs, J.S. Hahn, “How Does Canada Do It? A Comparison of Expenditures for Physicians’ Services in the United States and Canada,” New England Journal of Medicine 323, no. 13 (1990): 884–890 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Woolhandler, Campbell, and Himmelstein, “Costs of Health Care Administration”; James G. Kahn, Richard Kronick, Mary Kreger, and David N. Gans, “The Cost of Health Insurance Administration in California: Estimates for Insurers, Physicians, and Hospitals,” Health Affairs (Millwood) 24, no. 6 (2005): 1629–1639; Lawrence P. Casalino, Sean Nicholson, David N. Gans, Terry Hammons, Dante Morra, Theodore G. Karrison, and Wendy Levinson, “What Does It Cost Physician Practices to Interact with Health Insurance Plans,” Health Affairs (Millwood) web exclusive 28 (2009): w533–w543

- 62.Pol de Vos, “Health Report on Cuba. ‘No One Left Abandoned’: Cuba’s National Health System Since the 1959 Revolution,” International Journal of Health Services 35 (2005): 189–207; Pol de Vos and Patrick Van der Stuyft, “The Right to Health in Times of Economic Crisis: Cuba’s Way,” Lancet 374, no. 9701 (2009): 1575–1576; Tania M. Jenkins, “Patients, Practitioners, and Paradoxes: Responses to the Cuban Health Crisis of the 1990s,” Qualitative Health Research 18, no. 10 (2008): 1384–1400, esp. 1392 and 1399; World Health Organization, “Cuba; Country Coordination Strategy at a Glance,” April 2009, http://www.who.int/countryfocus/cooperation_strategy/ccsbrief_cub_en.pdf (accessed November 17, 2010); Jessica Moe, “Letter from Cuba,” Canadian Family Physician, 57 (2011): 458-459

- 63.E. Andaya, “The Gift of Health: Socialist Medical Practice and Shifting Material and Moral Economies in Post-Soviet Cuba,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 23, no. 4 (2009): 357–374 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Wolfe and Badgley. “How Much Is Enough?”; Howard J. Curzer, “Do Physicians Make Too Much Money?” Theoretical Medicine 13, no. 1 (1992): 45–65; Nancy S. Jecker and Eric M. Meslin, “United States and Canadian Approaches to Justice in Health Care: A Comparative Analysis of Health Care Systems and Values,” Theoretical Medicine 15, no. 2 (1994): 181–200; David L. Schiedermayer, “The Profession at the Fault Line: The Ethics of Physician Income,” in Bioethics and the Future of Medicine: A Christian Appraisal, eds. John F. Kilner, Nigel M. de S. Cameron, and David L. Schiedermayer (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 68–78 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Ontario, Ministry of Finance, Public Sector Salary Disclosure, at http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/publications/salarydisclosure/2010/ (accessed November 16, 2010)

- 66.A. Radwanski, “Sunshine Salary List Poses a Problem for McGuinty,” Globe and Mail, April 1, 2010, A7; Chad Skelton and Lori Culbert, “Number of Public Servants Earning More Than $100,000 Jumps 22 Per Cent in Two Year,” Vancouver Sun, 2010, http://www2.canada.com/vancouversun/news/westcoastnews/story.html?id=f65ebd81-c144-495e-bdee-be4c30b58008&k=36581 (accessed March 11, 2011)