Abstract

Within the sand fly genus Lutzomyia, the Verrucarum species group contains several of the principal vectors of American cutaneous leishmaniasis and human bartonellosis in the Andean region of South America. The group encompasses 40 species for which the taxonomic status, phylogenetic relationships, and role of each species in disease transmission remain unresolved. Mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) phylogenetic analysis of a 667-bp fragment supported the morphological classification of the Verrucarum group into series. Genetic sequences from seven species were grouped in well-supported monophyletic lineages. Four species, however, clustered in two paraphyletic lineages that indicate conspecificity—the Lutzomyia longiflocosa–Lutzomyia sauroida pair and the Lutzomyia quasitownsendi–Lutzomyia torvida pair. COI sequences were also evaluated as a taxonomic tool based on interspecific genetic variability within the Verrucarum group and the intraspecific variability of one of its members, Lutzomyia verrucarum, across its known distribution.

Introduction

The New World sand fly genus Lutzomyia (Diptera: Psychodidae) encompasses approximately 391 species morphologically subdivided in subgenera and species groups.1,2 In northwestern South America, along the Andean mountain range, the Verrucarum species group includes eight of the principal sand fly vectors of American cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL) and bartonellosis.1

The Verrucarum group consists of 40 species classified into three unranked series, Serrana, Townsendi, and Verrucarum (sensu Young and Duncan1), based on the phenotypic characteristics of the style and spines of the male genitalia. The Verrucarum series is characterized by two medial and two distal spines, the Serrana series is characterized by two distal spines and a slender medial spine, and the Townsendi series is characterized by three distal spines and an isolated basal spine.3 The females of the group are morphologically similar and difficult to identify reliably. A revision by Galati4 reorganized the group into seven series (Monticola, Pacae, Pia, Evansi, Verrucarum, Serrana, and Townsendi) based on a morphometric analysis of 88 morphological characters (two to six states per character).

Problems with morphological identifications in the Verrucarum group have led to difficulties in identifying leishmaniasis vectors,5,6 establishing their distributions,7 and clarifying their genetic relationships.5,8 The first attempt to move beyond classical taxonomy was the use of isozyme electrophoresis to distinguish members of the Townsendi series.9 Since then, species of the Verrucarum group have been subjected to taxonomic analysis by morphometrics,10 electron microscopy of eggs,11 karyotypic comparisons,12 and phylogenetic analysis of cytochrome b mitochondrial fragments.5 Galati's revision4 was given partial support by the analyses of 12S and 28S ribosomal DNA sequences,13 mitochondrial sequences,5 and nuclear isoenzymes.6 In these studies, phylogenetic relationships within the Verrucarum group remained, nevertheless, largely unresolved. In closely related taxonomic groups containing disease vector species, unambiguous species identification is necessary to ascertain the role of each species in disease transmission. Species identification within the Verrucarum group is unreliable when using female morphological structures.5 Consequently, the geographic limits of epidemiological risk cannot be delimited accurately,7 and planning meaningful control strategies becomes problematic. Furthermore, genetic data from each species will increase our understanding of the evolutionary relationships within the group,8 leading to a clarification of the evolutionary relationships between sand flies and the pathogens that they transmit.

Cytochrome c oxidase I mitochondrial (COI) sequences have been used to examine sibling species comparisons only within the L. longipalpis (Lutz and Neiva) complex.14 In the current study, COI sequences were used to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships among the three Verrucarum group series (sensu Young and Duncan1). Furthermore, genetic variation of L. verrucarum (Townsend) was surveyed across its known range to assess its homogeneity as a single species. The use of these sequences as taxonomic identification tools is also investigated.

Materials and Methods

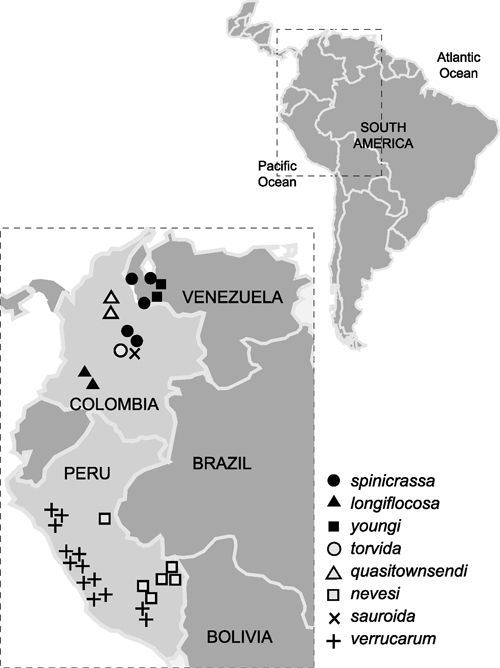

Between 2006 and 2008, 11 species of sand flies were collected in Peru and Colombia using standard white-light Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) traps as well as the light emitting diode (LED)-modified CDC traps described by Cohnstaedt and others15 (Figure 1). The L. verrucarum sensu stricto used in the intraspecific analysis was collected from six provinces—Amazonas, Cajamarca, Piura, Ancash, Lima, and Huancavelica (Tables 1 and 2). Geographic coordinates were collected using a Garmin Mark V GPS unit (datum from World Geodetic System 1984) and confirmed with Google Maps. L. walkeri (Newstead), assigned to the closely related subgenus Migonei, served as an outgroup. Only male sand flies were used in this study and were identified using the Young and Duncan taxonomic keys.1

Figure 1.

Distributions of the Verrucarum group sand flies used in the phylogenetic analysis. L. serrana (not shown) has a nearly continuous distribution throughout Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. L. robusta is morphologically similar to L. serrana and reported in similar areas.

Table 1.

Verrucarum group sand fly species used in the phylogenetic analysis

| Series | Species | No. samples | Country | Province | Accession numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verrucarum | L. andina | 1 | Colombia | Cundinamarca | FJ437283 |

| Verrucarum | L. nevesi | 1 | Colombia | Meta | FJ437270 |

| Serrana | L. serrana | 2 | Colombia | Boyacá | FJ437274 |

| Serrana | L. robusta | 2 | Peru | Cajamarca | FJ437280 |

| Townsendi | L. longiflocosa | 2 | Colombia | Huila | FJ437271; FJ437273 |

| Townsendi | L. quasitownsendi | 2 | Colombia | Boyacá | FJ437276; FJ437279 |

| Townsendi | L. sauroida | 2 | Colombia | Boyacá | FJ437284 |

| Townsendi | L. spinicrassa | 2 | Colombia | Boyacá | FJ437278; FJ437282 |

| Townsendi | L. torvida | 2 | Colombia | Cundinamarca | FJ437275; FJ437281 |

| Townsendi | L. youngi | 2 | Colombia | Mateguadua | FJ437272; FJ437277 |

| Lutzomyia (Migonei) | L. walkeri | 1 | Colombia | Huila | FJ437285; FJ437286 |

Table 2.

Lutzomyia verrucarum s.s. specimens from Peru

| Province | Haplotype name | Accession nos. | Province | Haplotype name | Accession nos. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huaylas | Huari08 | FJ437253 | Amazonas | Ama02 | FJ437240 |

| Huaylas | Marc06 | FJ437259 | Amazonas | Ama06 | FJ437241 |

| Huaylas | Maya2883 | FJ437262 | Amazonas | Ama10 | FJ437242 |

| Huaylas | Shan06 | FJ437266 | Amazonas | Ama11 | FJ437243 |

| Huaylas | Yuram01 | FJ437268 | Amazonas | Ama14 | FJ437244 |

| Huaylas | Yuram02 | FJ437269 | Cajamarca | Caj01 | FJ437245 |

| Purisima | Casma01 | FJ437249 | Cajamarca | Caj07 | FJ437246 |

| Purisima | Yumpe15 | FJ437267 | Cajamarca | Caj09 | FJ437247 |

| Conchucos | Chngas11 | FJ437250 | Cajamarca | Caja05 | FJ437248 |

| Conchucos | Hnco02 | FJ437251 | Piura | Piu02 | FJ437263 |

| Conchucos | Masin15 | FJ437260 | Piura | Piu17 | FJ437264 |

| Conchucos | Masn17 | FJ437261 | Piura | Piu22 | FJ437265 |

| Lima | Lim04 | FJ437254 | Lima | Lim17 | FJ437257 |

| Lima | Lim05 | FJ437255 | Lima | Lim28 | FJ437258 |

| Lima | Lim07 | FJ437256 | Huancavelica | Huan811 | FJ437252 |

DNA extractions and preparation for amplification have been previously described by Beati and Keirans.16 COI primers LCOI490 (5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′) and HCO2198 (5′-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′) described by Folmer and others17 for metazoan invertebrates amplified approximately 700 sand fly bp, of which 667 were used. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 4 minutes followed by 20 cycles of denaturation (95°C) for 30 seconds, annealing (55–0.3°C/cycle) for 30 seconds, and elongation (70oC) for 35 seconds. The first 20 amplifications were followed by 25 additional cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 48°C for 1 minute, and 70°C for 35 seconds. The program was terminated with a 5-minute elongation step at 70°C. The PCR products were then purified by mixing with one part exonuclease I (NE Biol), antarctic phosphotase (NE Biol), one part PCR 10× buffer, and 17 parts biologically pure water, which was incubated sequentially at 37°C and 80°C for 15 minutes each. The purified sequences were bidirectionally sequenced at the DNA Analysis Facility, Science Hill (Yale University).

DNA sequences were aligned with a Clustal V algorithm using Lasergene software (DNAstar, Madison, WI). Base pair content and coding positions were computed using Mega 4.0.18 Kimura two-parameter (K2P) genetic divergences between DNA sequences were calculated using the computer program DNAsp.19 Model parameters for maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree construction were generated with Modeltest 3.7.20 The tree was generated by Bayesian analysis, Mr. Bayes 3.1,21 using the model parameters selected by Modeltest. One million iterations were performed on the data using four chains, and trees were recorded every 1,000th generation. A posteriori probability branch support was calculated by the 50% majority rule consensus of the recorded trees. The first 250 trees, recovered before the probability values converged and stabilized, were discarded before calculating posterior probabilities for each branch. To visualize the relationships between closely related haplotypes, a gene network was constructed using statistical parsimony.22

Results

Eleven species from three series were recovered from the Peru–Colombia collections. The species from each series were as follows: (1) the Verrucarum series: L. verrucarum, L. andina (Osorno, Osorno-Mesa, and Morales), and L. nevesi (Damasceno and Arouck); (2) the Serrana series: L. serrana (Damasceno and Arouck) and L. robusta (Galati, Caceres, and LePont); and (3) the Townsendi series: L. longiflocosa (Osorno-Mesa, Morales, Osorno, and Munoz de Hoyos), L. sauroida (Osorno-Mesa, Morales, and Osorno), L. torvida (Young, Morales, and Ferro), L. quasitownsendi (Osorno, Osorno-Mesa, and Morales), L. youngi (Feliciangeli and Murillo), and L. spinacrassa (Morales, Osorno-Mesa, Osorno, and Munoz de Hoyos). The 56 specimens of L. verrucarum were collected from eight localities throughout the species range.

COI sequences were obtained from 72 specimens (Table 3). The alignment resulted in a 667 bp matrix, with 162 variable nucleotide positions (Table 4). Indels and nonsense/stop codons were not detected. The sequences were adenosine and thymine (AT)-rich, especially in the first and third codon positions (Table 5). All the base pair substitutions were synonymous in the Verrucarum series. Sequences of the two species of the Serrana series had amino acid changes in the alignment at positions 38 (valine to isoleucine) and position 482 (threonine to serine) relative to the base sequence of the Verrucarum series. In the Townsendi series, only L. sauroida had a serine to lysine amino acid change at position 369.

Table 3.

Geographic locations of L. verrucarum specimens from Peru

| Province | Region | Township | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancash | Purisima | Casma | 9° 29′ 35″ S | 77° 59′ 37″ W | 1,580 |

| Ancash | Purisima | Yumpe | 10° 15′ 29″ S | 77° 29′ 13″ W | 2,083 |

| Ancash | Huaylas | Yuracmarca | 8° 44′ 31″ S | 77° 53′ 18″ W | 1,623 |

| Ancash | Huaylas | Caraz | 8° 58′ 59″ S | 77° 49′ 18″ W | 2,235 |

| Ancash | Huaylas | Yungay | 9° 10′ 37″ S | 77° 44′ 48″ W | 2,476 |

| Ancash | Huaylas | Carhuaz | 9° 19′ 28″ S | 77° 35′ 57″ W | 2,782 |

| Ancash | Huaylas | Huaraz | 9° 31′ 10″ S | 77° 32′ 14″ W | 3,018 |

| Ancash | Conchucos | Sihuas | 8° 33′ 15″ S | 77° 37′ 51″ W | 2,682 |

| Ancash | Conchucos | Huayllan | 8° 49′ 54″ S | 77° 26′ 19″ W | 3,143 |

| Ancash | Conchucos | Lucma | 8° 55′ 59″ S | 77° 25′ 11″ W | 3,941 |

| Ancash | Conchucos | Masin | 9° 21′ 59″ S | 77° 05′ 48″ W | 2,537 |

| Ancash | Conchucos | Chingas | 9° 07′ 04″ S | 76° 59′ 25″ W | 2,841 |

| Ancash | Conchucos | San Marcos | 9° 34′ 03″ S | 77° 10′ 41″ W | 3,141 |

| Amazonas | Bongara | Janzan | 5° 56′ 57″ S | 77° 57′ 25″ W | 2,630 |

| Piura | Huancabamba | Sondorillo | 5° 21′ 05″ S | 79° 26′ 48″ W | 2,007 |

| Cajamarca | Jaen | San Jose del Alto | 5° 25′ 43″ S | 79° 07′ 6″ W | 1,565 |

| Lima | Huarochiri | Huinco | 11° 45′ 54″ S | 76° 35′ 41″ W | 2,930 |

| Huancavelica | Huaytara | Santo Domingo de Capillas | 13° 41′ 27″ S | 75° 14′ 17″ W | 2,982 |

Table 4.

The 162 variable nucleotide positions of the 667-bp cytochrome c oxidase sequence

| Collection | Nucleotide position | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series | Location | Sequence name | 22 | 25 | 34 | 38 | 40 | 43 | 46 | 49 | 50 | 58 | 67 | 70 | 79 | 82 | 85 | 91 | 92 | 103 | 106 | 109 | 115 | 121 | 127 | 130 | 133 | 139 | 145 | 154 | 157 | 160 | 163 | 166 | 181 | 184 | 193 | 197 | 199 | 202 | 205 | 206 | 208 | 211 | 212 | 214 | 217 | 220 | 226 | 229 | 232 | 235 | 238 | 253 | 256 | 263 | 266 | 268 | 271 | 274 | 277 | 283 | 284 | 286 | 287 | 289 | 295 | 298 | 301 | 307 | 313 | 316 | 322 | 325 | 328 | 334 | 337 | 343 | 346 | 349 | 352 | 355 | 361 | 362 | 364 | 369 | 370 | 373 | 376 | 379 | 382 | 386 | 388 | 391 | 397 | 400 | 401 | 403 | 407 | 415 | 418 | 421 | 424 | 428 | 430 | 433 | 436 | 442 | 451 | 466 | 475 | 478 | 481 | 482 | 484 | 485 | 490 | 496 | 499 | 500 | 508 | 514 | 517 | 520 | 523 | 526 | 529 | 532 | 533 | 535 | 536 | 538 | 539 | 541 | 547 | 550 | 553 | 556 | 562 | 565 | 568 | 574 | 578 | 580 | 586 | 589 | 595 | 596 | 601 | 604 | 607 | 610 | 613 | 616 | 619 | 622 | 628 | 631 | 634 |

| Verrucarum | Amazonas | Ama02 | A | C | T | G | A | A | T | T | T | T | A | T | G | T | C | T | T | T | T | A | T | A | T | A | T | T | T | T | T | A | A | A | A | A | C | C | T | T | T | T | A | A | C | T | A | C | T | A | A | T | T | A | C | T | C | T | T | T | T | C | C | T | C | C | A | C | A | A | T | A | A | T | T | T | T | C | T | A | T | T | T | G | T | G | A | A | T | A | T | C | T | A | C | T | T | A | T | A | T | T | A | C | T | A | T | C | A | A | A | G | T | A | T | T | T | A | C | T | T | T | T | A | T | A | T | A | T | A | T | A | C | A | T | T | T | T | A | A | T | A | C | T | T | T | T | T | T | C | A | C | T | C | T | A | A | A | C |

| Verrucarum | Amazonas | Ama06 | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Amazonas | Ama10 | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Amazonas | Ama11 | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Amazonas | Ama14 | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Cajamarca | Caj01 | G | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | C | C | · | · | T | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Cajamarca | Caj07 | G | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | C | C | · | · | T | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Cajamarca | Caj09 | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | C | · | · | T | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Cajamarca | Caja05 | G | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | C | C | · | · | T | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Piura | Piu02 | · | · | · | · | · | G | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Piura | Piu17 | · | · | · | · | · | G | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Piura | Piu22 | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | G | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Conchucos | Hnco02 | G | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | C | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | G | T |

| Verrucarum | Conchucos | Sihua07 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | C | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Conchucos | Chngas11 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | C | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | G | T |

| Verrucarum | Conchucos | Masn17 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | C | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | G | T |

| Verrucarum | Conchucos | Lverru | G | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | C | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | G | G | T |

| Verrucarum | Conchucos | Lverru2 | G | · | C | · | · | G | · | · | C | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | G | T |

| Verrucarum | Purisima | Casma01 | · | · | G | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | G | G | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Purisima | Yumpe15 | · | · | A | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | G | G | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Purisima | Yuram01 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | G | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Purisima | Yuram02 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Purisima | Maya2883 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | G | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Purisima | Shan06 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | G | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Huancavelica | Huan811 | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | G | G | · | T |

| Verrucarum | Lima | Lim04 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | G | · | · | T |

| Verrucarum | Lima | Lim05 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | G | G | · | T |

| Verrucarum | Lima | Lim07 | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | G | · | · | T |

| Verrucarum | Lima | Lim17 | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | G | G | · | T |

| Verrucarum | Lima | Lim28 | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | G | · | T |

| Verrucarum | Colombia | Landina | G | · | A | · | C | T | C | · | · | · | · | · | C | C | A | · | · | C | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | T | · | · | C | · | T | A | C | · | C | · | · | · | · | G | T | · | · | · | C | C | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | A | · | T | · | · | G | A | A | · | A | · | A | · | A | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | A | · | · | T | A | · | · | C | C | T | · | G | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | T | · | C | A | C | · | C | · | C | · | T | · | C | A | · | · | · | · | A | T | · | · | C | T | · | · | C | A | · | · | · | · | A | T | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | T | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Verrucarum | Colombia | Lnevesi | · | · | A | · | · | · | C | C | · | · | T | A | T | · | T | · | · | · | C | G | · | · | · | · | A | C | A | · | · | · | T | G | T | · | · | T | A | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | T | A | · | · | A | A | · | · | · | T | T | T | T | T | A | · | · | · | A | A | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | C | T | C | G | C | · | T | T | A | · | A | T | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | C | C | · | T | · | C | A | A | · | · | T | A | T | · | · | C | T | · | T | · | A | · | G | T | · | · | C | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | A | C | · | · | · | A | · | G | · | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Llongifl | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | A | C | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | · | · | · | G | T | C | · | · | A | · | T | A | C | C | · | A | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | T | · | G | G | · | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | C | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | T | · | C | T | T | A | G | C | T | T | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | T | · | T | · | C | C | T | C | C | T | · | C | G | · | · | T | G | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | C | G | · | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Llongifl2 | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | A | C | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | G | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | · | G | T | C | · | · | A | · | T | A | C | C | · | A | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | T | · | G | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | T | · | C | T | T | A | G | C | T | T | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | G | · | · | T | · | T | · | C | C | T | C | C | T | · | C | G | · | · | T | G | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | C | G | · | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Lsauroida | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | A | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | G | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | · | G | T | C | · | · | A | · | T | A | C | C | · | · | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | T | · | G | G | · | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | C | · | C | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | T | · | C | T | T | A | G | C | T | T | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | T | · | T | · | C | C | T | C | C | T | · | C | G | · | · | T | · | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | C | G | · | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Lyoungi | G | · | · | · | · | G | · | A | · | C | · | A | T | C | A | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | T | · | · | · | C | C | G | · | · | · | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | A | C | T | A | · | · | · | A | T | A | · | T | · | T | · | T | · | G | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | T | · | A | T | T | A | · | · | T | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | A | · | · | C | · | T | · | C | C | · | C | C | T | · | C | A | · | · | T | · | C | T | T | A | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Lyoungi2 | G | · | · | · | · | G | · | A | · | C | · | A | T | C | A | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | C | C | G | · | · | · | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | A | C | T | A | · | · | · | A | T | A | · | T | · | T | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | T | · | A | T | T | A | · | · | T | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | A | · | · | C | · | T | · | C | C | · | C | C | T | · | C | A | · | · | T | · | C | T | T | A | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Lspini | G | · | · | · | · | G | · | A | · | · | · | A | T | C | A | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | C | C | · | · | G | · | · | T | T | G | A | C | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | · | G | T | · | · | · | A | C | T | G | C | · | · | A | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | T | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | G | A | · | · | T | A | · | T | · | · | G | · | T | · | A | T | T | A | · | · | T | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | C | · | T | · | C | C | · | C | C | T | · | C | A | · | · | T | · | C | T | T | A | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | G | G | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Lspini2 | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | T | C | A | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | C | C | · | · | G | · | · | T | T | G | A | C | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | · | G | T | · | · | · | A | C | T | G | C | · | · | A | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | T | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | T | A | · | T | · | · | G | · | T | · | A | T | T | A | · | · | T | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | C | · | T | · | C | C | · | C | C | T | · | C | A | · | · | T | · | C | T | T | A | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | G | · | G | G | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Ltorvida | G | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | A | C | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | · | G | C | · | · | G | A | · | T | A | C | · | · | A | T | A | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | G | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | T | T | A | · | · | T | T | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | G | · | · | T | · | T | · | T | C | T | C | T | T | · | · | A | · | · | T | G | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | C | · | A | T | · | · | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Ltorvida2 | G | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | A | C | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | · | G | C | · | · | G | A | · | T | A | C | · | · | A | T | A | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | T | T | A | · | · | T | T | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | G | · | · | T | · | T | · | T | C | T | C | T | T | · | · | A | · | · | T | G | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | C | · | A | T | · | · | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Lquasit | G | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | A | C | A | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | · | G | C | · | · | · | A | · | T | A | · | · | · | A | T | A | · | A | C | · | · | T | · | · | · | C | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | T | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | T | T | A | · | · | T | T | G | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | G | · | · | T | · | T | · | T | C | T | C | T | T | · | · | A | · | · | T | G | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | C | · | A | T | · | · | · |

| Townsendi | Colombia | Lquasit2 | G | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | A | A | C | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | · | · | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | T | A | G | · | C | G | C | · | · | G | A | · | T | A | C | · | · | A | T | A | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | G | · | · | · | T | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | T | T | A | · | · | T | T | G | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | C | G | · | · | T | · | T | · | T | C | T | C | T | T | · | · | A | · | · | T | G | · | T | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | C | · | A | T | · | · | · |

| Serrana | Peru | Lrobusta | · | · | A | A | T | T | · | C | · | · | · | A | A | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | C | · | A | T | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | C | T | · | T | A | G | T | · | · | C | · | · | · | A | · | · | A | C | · | · | T | · | A | T | A | T | A | · | T | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | T | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | G | · | T | A | T | A | · | T | · | C | T | · | · | · | · | T | · | G | T | A | T | T | G | · | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | T | · | T | · | T | · | · | C | T | T | · | C | A | A | A | T | · | · | T | · | A | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Serrana | Colombia | Lserrana | · | · | G | A | T | T | · | C | · | C | · | A | · | C | A | · | C | · | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | C | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | T | · | T | A | · | · | · | G | C | · | · | · | A | · | T | G | · | · | · | T | · | A | T | A | T | A | · | T | A | G | · | · | · | · | · | · | C | T | · | · | · | · | A | · | · | · | · | T | A | T | A | · | T | · | C | T | · | · | · | · | C | · | G | · | A | T | T | · | · | A | · | T | · | · | · | · | T | · | · | · | · | T | · | T | · | T | · | · | C | T | T | · | · | A | A | A | T | · | C | T | · | A | · | · | C | · | · | T | · | T | · | · | · | · | · | G | · |

Table 5.

Cytochrome oxidase sequence nucleotide composition

| Species | Total | Position 1 | Position 2 | Position 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | A | G | Total | T-1 | C-1 | A-1 | G-1 | T-2 | C-2 | A-2 | G-2 | T-3 | C-3 | A-3 | G-3 | |

| L. verrucarum | 39.5 | 17.3 | 27.2 | 16.0 | 667.0 | 50.2 | 8.1 | 39.6 | 2.1 | 25.1 | 17.7 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 43.0 | 26.1 | 13.7 | 17.1 |

| L. andina | 36.2 | 19.3 | 28.5 | 16.0 | 657.0 | 40.9 | 14.1 | 43.2 | 1.8 | 24.8 | 17.4 | 28.4 | 29.4 | 42.9 | 26.5 | 13.7 | 16.9 |

| L. nevesi | 37.0 | 18.0 | 28.4 | 16.6 | 649.0 | 44.2 | 9.7 | 43.3 | 2.8 | 24.1 | 18.1 | 28.2 | 29.6 | 42.6 | 26.4 | 13.4 | 17.6 |

| L. serrana | 39.1 | 16.8 | 27.9 | 16.2 | 667.0 | 47.1 | 8.1 | 41.7 | 3.1 | 27.0 | 16.2 | 28.4 | 28.4 | 43.2 | 26.1 | 13.5 | 17.1 |

| L. robusta | 38.6 | 16.7 | 28.5 | 16.2 | 642.0 | 47.7 | 7.0 | 43.5 | 1.9 | 25.2 | 15.9 | 29.4 | 29.4 | 43.0 | 27.1 | 12.6 | 17.3 |

| L. sauroida | 39.7 | 16.8 | 27.1 | 16.3 | 667.0 | 46.6 | 10.8 | 39.0 | 3.6 | 29.3 | 13.5 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 43.2 | 26.1 | 14.0 | 16.7 |

| L. longiflocosa | 39.6 | 16.8 | 27.2 | 16.5 | 667.0 | 46.2 | 10.8 | 39.5 | 3.6 | 29.3 | 13.5 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 43.2 | 26.1 | 13.5 | 17.1 |

| L. youngi | 39.1 | 16.5 | 28.3 | 16.2 | 667.0 | 46.4 | 8.1 | 42.8 | 2.7 | 27.5 | 15.3 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 43.2 | 26.1 | 13.5 | 17.1 |

| L. spinicrasa | 38.9 | 16.6 | 27.5 | 17.1 | 667.0 | 44.8 | 9.4 | 40.4 | 5.4 | 28.4 | 14.4 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 43.5 | 25.9 | 13.5 | 17.1 |

| L. torvida | 39.4 | 15.9 | 28.1 | 16.6 | 650.5 | 47.4 | 7.6 | 42.1 | 3.0 | 27.9 | 13.7 | 28.9 | 29.6 | 43.0 | 26.6 | 13.2 | 17.3 |

| L. quasitownsendi | 39.7 | 16.3 | 27.7 | 16.4 | 667.0 | 46.9 | 8.8 | 41.1 | 3.4 | 28.8 | 14.0 | 28.4 | 28.8 | 43.2 | 26.1 | 13.5 | 17.1 |

| L. walkeri | 36.6 | 18.5 | 29.3 | 15.8 | 658.0 | 41.2 | 12.5 | 45.0 | 1.4 | 25.6 | 16.4 | 29.0 | 29.0 | 42.9 | 26.5 | 13.7 | 16.9 |

| Average | 38.8 | 17.0 | 27.9 | 16.3 | 662.0 | 46.3 | 9.3 | 41.4 | 2.9 | 27.0 | 15.5 | 28.5 | 29.0 | 43.1 | 26.3 | 13.5 | 17.1 |

Phylogenetic analysis of Verrucarum group species using Bayesian analysis indicated clear monophyletic clustering of the three series (Figure 2). Analysis parameters selected by Modeltest were GTR + I + G, shape = 1.74, and pinvar = 0.64. The deep rooted branch of the Verrucarum series indicated an early divergence from the sister clades corresponding to the Serrana and Townsendi series. Based on monophyly of each corresponding lineage, individual species assignments were made for seven species—L. verrucarum, L. andina, L. nevesi, L. serrana, L. robusta, L. youngi, and L. spinicrassa. Four species, L. longiflocosa, L. sauroida, L. quasitownsendi, and L. torvida, clustered as two paraphyletic clades.

Figure 2.

The phylogenetic tree was obtained by Bayesian analysis of the COI sequence. A posteriori probabilities are shown above branches. Species name and specimen code are included on the branch tips. The number of specimens with the same haplotype was listed in parenthesis.

L. verrucarum s.s. phylogenetic analysis detected three main monophyletic clades: the Amazonas clade, the northeastern Andean clade, and the southwestern Andean clade (Figure 3). Bayesian analysis parameters selected by Modeltest were TVM + I + G, shape = 0.51, and pinvar = 0.60. The basal Amazonas clade encompassed eight specimens from the Amazonas province. The Amazonas clade diverged early from the northeastern and southwestern Andean clades.

Figure 3.

The phylogenetic tree was obtained by Bayesian analysis of COI sequence data, and a posteriori probabilities are shown above branches. Specimen name and code are listed on branch tips, and the number of specimens with the same haplotype was listed in parenthesis.

The northeastern Andes clade consisted of three monophyletic clades. The Cajamarca and the Piura clades included the collections from the northern provinces Cajamarca (10 specimens) and Piura (6 specimens). The third clade, Ancash-Conchucos Valley, was formed by 18 specimens sampled within the interandean Conchucos Valley. The Sihua07 individual was collected from the town of Sihuas located at the northern collection site within the Conchucos Valley. Individuals from the other collection sites formed a single clade and were taken from the southern and southcentral parts of the valley. The southwestern clade consisted of three monophyletic clades. Collections from the Ancash-Huaylas Valley formed the most basal clade. The Ancash-Purisma Valley and Lima clade diverged from the Ancash-Huaylas Valley clade before separating. The Purisma Valley clade consisted of the northern-most (Casma01) and southern-most (Yumpe 15) collection points in the valley. The third clade consisted of samples from the southern-most provinces, Lima and Huancavelica. Sample Huan811, from the Huancavelica province, was located within the Lima clade.

Genetic network analysis of the L. verrucarum geographic populations resulted in five unconnected networks using statistical parsimony with a 95% confidence limit (Figure 4). The eastern Andean populations each formed independent networks corresponding to Amazonas, Cajamarca, Piura, Ancash, and the Conchucos Valley. The eastern Andean population networks consisted of clusters of 1–2-bp variants, with the exception of Sihuas07 and Piura22. The western Andean population was a single connected network corresponding to Ancash, the Purisma and Huaylas Valleys, Lima, and Huancavelica. The northern/western Andean specimens from the Purisma Valley (Casma01 and Yumpe 15) were separated by 5 bp from the Huaylas Valley population. The Huaylas Valley population was 5 bp divergent from the Lima and Huancavelica populations.

Figure 4.

The geographic populations of L. verrucarum formed five unconnected genetic networks (based on statistical parsimony with a 95% connection limit) corresponding to the Amazonas, Cajamarca, Piura, Ancash (Conchucos Valley), and the western Andean populations. The western Andean network consisted of Ancash (Purisima and Huaylas Valleys), Lima, and Huancavelica populations. Species name and code number are listed in the ovals. Multiple identical haplotypes were indicated by parenthesis.

Genetic divergence within the Verrucarum series was 14.9% between its three species, 5.2% between the six Townsendi species, and 4.2% between the two Serrana species. Intraspecific genetic variation among L. verrucarum s.s. geographic locations differed by 0.6–3.4% (Table 6). L. verrucarum s.s. from the western side of the Andes (Purisima, Huaylas, Lima, and Huancavelica) was more similar than populations from the eastern side (Conchucos, Amazonas, Cajamarca, and Piura). Genetic differentiation of the L. verrucarum s.s. by geographic locations ranged from 0.07 to 0.89.

Table 6.

Genetic divergence and genetic distance of L. verrucarum populations

| Purisima | Huaylas | Lima | Huancavelica | Conchucos | Amazonas | Cajamarca | Piura | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purisima | 0.003 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.037 | 0.032 |

| Huaylas | 1.4 | 0.013 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.029 | 0.025 |

| Lima | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.029 | 0.025 | 0.039 | 0.033 |

| Huancavelica | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.6 | n/a | 0.030 | 0.024 | 0.040 | 0.034 |

| Conchucos | 2.8 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 0.005 | 0.036 | 0.028 | 0.029 |

| Amazonas | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0.003 | 0.036 | 0.028 |

| Cajamarca | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 0.003 | 0.026 |

| Piura | 3.1 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 0.009 |

Lower diagonal values represent percent genetic divergence calculated using Kimura 2 parameter. Upper diagonal values represent genetic distance using the model TVM + G + I. The diagonal values represent intrapopulational distance.

Discussion

The COI sequences can be an informative molecular tool for resolving phylogenetic relationships at the series and species level among recently evolved lineages within the Verrucarum group. However, comparisons of the genetic variability among and within series and species raise a number of questions about the taxonomic status of several species in this group. COI barcoding of sand fly species is appropriate for identifying potential disease vector specimens but must be used with caution when declaring new species designations based only on genetic divergence. Similar caution is necessary when using this fragment for phylogenetic reconstruction. Although apparently adequate for the purpose of the current study, the inclusion of one or more nuclear genes will increase the power of inferences drawn, because mitochondrial lineages have been shown to not always agree with nuclear gene lineages.

The COI primers amplified a single fragment in each sand fly. The absence of nonsense mutations in the alignment indicated an absence of pseudogenes. The AT-rich bias notable in the first and third codon position is common among invertebrates.23,24 Synonymous base pair mutations implied little phenotypic change and little or no selective pressure on the haplotypes. The three codons characterized by non-synonymous mutations, two in the Serrana series, maintained amino acid charge and polarity. The amino acid change in L. sauroida maintained polarity, but the amino acid charge became basic. Within the Serrana series, the amino acid changes were conserved in the two species and suggested a mutation early in the evolution of this series but after divergence from the Townsendi series. Within the L. verrucarum sequences, fixed base pair changes were found in geographically distinct populations, implying recent population level divergence.

The COI phylogeny indicated that the basal Verrucarum series lineage probably diverged before the Townsendi and Serrana series. This is the first molecular evidence of the ancestry and ranking within species of the Verrucarum group. The phylogenetic positions of three series (Verrucarum, Serrana, and Townsendi: sensu Young and Duncan1) in the Verrucarum group have been positioned unambiguously and support the taxonomic reorganization by Galati4 based on morphology. Young and Duncan1 and Galati4 placed 10 of 11 species treated herein within the same supported series. Only L. nevesi was moved to a newly formed series, the Evansi series in the Galati4 revision. The basal nature of L. nevesi and the high interspecies divergence between L. nevesi and the remaining species of the L. verrucarum series supported the inclusion of this species in a series distinct from Verrucarum. Additional species from Galati's4 Evansi series must be sampled to confirm this taxonomic separation, such as L. evansi (Nunez-Tovar), L. marononensis (Galati, Caceres, and Le Pont), and L. ovallesi (Ortiz).

COI sequences from 7 of 11 species formed monophyletic clades. The occurrence of two paraphyletic clades, the L. sauroida–L. longiflocosa and L. torvida–L. quasitownsendi, indicated that these four species require taxonomic reassessment. Based on enzyme electrophoresis results, Kreutzer and others9 suggested that L. sauroida, L. longiflocosa, and L. quasitownsendi may be conspecific. The current results support the conspecific relationship between L. sauroida and L. longiflocosa, and potentially, L. quasitownsendi based on the short branch lengths between clades. Similarly, L. torvida and L. quasitownsendi, species found in neighboring valleys, are morphologically similar and may form a cline of local variation. Nonetheless, L. torvida was distinguishable by diagnostic alleles with enzyme electrophoresis.9

Incomplete lineage sorting within the Townsendi series species can explain the close genetic similarities between species. Similarly, mitochondrial introgression has been reported between the species L. townsendi (Ortiz and Ortiz) and L. youngi5 and within the species complex L. intermedia (Lutz and Neiva).25 Additional specimens and species must be sequenced to better evaluate the taxonomic status of the clades. Increasing the number of species from the Verrucarum, Serrana, Pia, and Evansi series will also be necessary to clarify or support the phylogenetic relationships among the series as currently conceptualized as well as to evaluate the positions of the Pia and Evansi series within the phylogeny.

Phylogenetic analysis of L. verrucarum s.s. revealed a set of well-supported monophyletic clades that clustered by geographic collection area. Gene network analysis also supported the formation of separate clades as visualized by unconnected networks (Figure 4). The genetic distance among L. verrucarum populations indicated highly isolated populations, with little or no genetic exchange over extended periods of time. Analogous genetic structuring was observed in L. shannoni populations in Colombia26 and the L. longipalpis of Central and South America.14 The L. verrucarum populations in the northeastern Andes had a high genetic distance compared with those in the southwest. Sand flies are considered to have limited dispersal capabilities based on two relevant studies using New World sand flies. In mark–release–recapture experiments involving hundreds of flies, sand fly dispersal was estimated to be less than 200 m for L. shannoni27 and 500 m for L. longipalpis.28 Limited dispersal capability produces population structuring by distance, and the structuring is enhanced further in the presence of abiotic barriers. The heterogeneous terrain of the Andes, combined with the low dispersal capacity of the sand flies, has restricted their ability to colonize new areas and migrate between valley systems. In these conditions, allopatric speciation may progress rapidly to produce genetically distinct but morphologically similar individuals. The morphological homogeneity seen within species series (i.e., the Townsendi series5) or species complexes (L. longipalpis29) exemplifies this process. Furthermore, although separated by high mountains, the valleys of Ancash, Peru, are ecologically very similar. Their relatively homogeneous environmental conditions may have engendered little selective pressure on morphologically adaptive characters, thereby leading to cryptic speciation. However, careful transect sampling through potential dispersal routes within the Peruvian Andes and transpopulation mating experiments will provide the necessary additional information for species-level divergences implied by the current COI data.

Within the Verrucarum group, Serrana (4.2%) and Townsendi (5.2%) intraseries genetic divergence was similar to the intraspecific genetic divergence of Anopheles annulipes sensu lato (Walker; mean = 4%, range = 0.3-6.8%).30 The 17 morphologically similar sibling species of the A. annulipes species complex is a case of extreme diversification, with nearly complete isolation on the island continent of Australia. In contrast, the Verrucarum series divergence was threefold higher (14.9%). These comparisons may be somewhat misleading, because L. nevesi included as a Verrucarum series member has also been classified as part of the Evansi series.4 Furthermore, L. verrucarum sample numbers were greater than the other sand fly specimens, and the samples may have included an undescribed species complex. Additional specimens from several geographic sites for species in the Serrana and Townsendi series may increase intraseries divergence values and possibly, monophyly of species.

Genetic divergence (0.1–3.6%) within geographic populations of L. verrucarum was similar to that of species within the A. annulipes s.l. complex (mean = 0.4%, range = 0.0–2.0%).30 Under closer scrutiny, morphological traits may be discovered that will distinguish the isolated L. verrucarum valley populations as different taxa. This has precedence in other phlebotomine sand fly species, such as in clusters formerly regarded as single species (i.e., L. longipalpis)31 and the eight species of the Townsendi series.1,5 Taxonomy of the Townsendi series in Colombia has been emphasized, because four of these species (L. quasitownsendi, L. spinacrassa, L. longiflocosa, and L. youngi) are major vectors of leishmaniasis and must be distinguished from the non-vector species.8

The high genetic variability within L. verrucarum populations emphasized the importance of testing several sand fly specimens from diverse geographic locations. Although the geographic range of most species used herein was small (Figure 1), genetic differentiation reported within the limited habitat of L. verrucarum was high. The phylogenetic relationships among the species of the Verrucarum group (other than L. verrucarum s.s.) were based on few individuals from single geographic areas. Adding species, specimens, and geographic locations will be necessary to capture the genetic variability within the sand fly species if COI comes to be used in a barcoding capacity. COI barcoding has served as a rapid and reliable means of sampling morphologically similar species for genetic variability. Additionally, Besansky and others32 justified barcoding for species classification because of the importance of identification for medically important insects, such as sand flies. If all COI sequences have evolved at a uniform rate within the Verrucarum group, the representation of the Townsendi series main lineages as different species implies that the populations of L. verrucarum form a species complex because of a comparable genetic divergence. Conversely, if L. verrucarum is considered a single species, then the species currently included in the Townsendi series have a similar conspecific status. In both cases, the high genetic divergence between geographic populations of L. verrucarum s.s. requires resolution and may preclude the use of COI sequences as a barcoding tool for the description of new species and potentially, for the identification of sand flies.

In summary, phylogenetic analyses of COI sequences provided an initial well-supported reconstruction of the genetic relationships between sand fly lineages of recent origin. Nevertheless, the evolutionary history of the Verrucarum group species will be better resolved when representatives of all species and series are included in the same phylogenetic tree as well as specimens from diverse sites within their geographic distribution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lynn A. Jones for her taxonomic expertise identifying sand flies, Dr. Virginia Hodgkinson for her comments on the manuscript, and Nicolas Patricio for his help with the sand fly capture in Peru. A special thanks to the Caccone/Powell Lab at Yale University and the Laboratorio de Entomología del Instituto Nacional de Salud for the Colombian collections (assisted by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-AI56254). A Down's Fellowship Grant to L.W.C. funded sand fly collections in Peru, and molecular work was funded by National Institutes of Health Program Grant U19-A1065866 and Training Grant PTG-2T32-AI07404.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Lee W. Cohnstaedt, Arthropod-Borne Animal Disease Research Unit, Center for Grain and Animal Health Research, Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Manhattan, KS, E-mail: Lee.Cohnstaedt@ars.usda.gov. Lorenza Beati, Southern University, Institute of Arthropodology and Parasitology, Statesboro, GA, E-mail: LorenzaBeati@Georgiasouthen.edu. Abraham G. Caceres, Departmento Académico de Microbiologia Médica, Facultad de Medina Humana, Universidad Nacional, Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru and Laboratorio de Entomología, Instituto Nacional de Salud, Lima, Peru, E-mail: agcl2011@gmail.com. Cristina Ferro, Instituto Nacional de Salud, Bogotá, Colombia. Leonard E. Munstermann, Yale School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, CT, E-mail: Leonard.Munstermann@yale.edu.

References

- 1.Young DG, Duncan MA. Guide to the Identification and Geographic Distribution of Lutzomyia Sand Flies in Mexico, the West Indies, Central and South America (Diptera: Psychodidae) Gainesville, FL: Associated Publishers: American Entomological Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Computer Identification of Phlebotomine sandflies of the Americas (CIPA) Group . Computer-Aided Identification of Phlebotomine Sandflies of America. 1997. http://cipa.snv.jussieu.fr/ Available at. Accessed January 15, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bejarano EE, Duque P, Velez ID. Taxonomy and distribution of the series pia of the Lutzomyia verrucarum group (Diptera: Psychodidae), with a description of Lutzomyia emberai n. sp. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:833–841. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galati EAB. In: Morfologia e taxonomia. Flebotomíneos do Brasil. Rangel EF, Lainson R, editors. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Editora Fiocruz; 2003. pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Testa JM, Montoya-Lerma J, Cadena H, Oviedo M, Ready PD. Molecular identification of vectors of Leishmania in Colombia: mitochondrial introgression in the Lutzomyia townsendi series. Acta Trop. 2002;84:205–218. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torgerson DG, Lampo M, Velazquez Y, Woo PT. Genetic relationships among some species groups within the genus Lutzomyia (Diptera: Psychodidae) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:484–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bejarano EE, Sierra D, Velez ID. New findings on the geographic distribution of the Verrucarum group (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Colombia. Biomedica. 2003;23:341–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bejarano EE, Rojas W, Uribe S, Velez ID. Systematics of the Lutzomyia species of the Verrucarum Theodor group, 1965 (Diptera: Psychodiadae) Biomedica. 2003;23:87–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreutzer RD, Palau MT, Morales A, Ferro C, Feliciangeli D, Young DG. Genetic relationships among phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in the Verrucarum species group. J Med Entomol. 1990;27:1–8. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/27.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feliciangeli MD, Arredondo C, Ward R. Phlebotomine sandflies in Venezuela—review of the Verrucarum-species group (in part) of Lutzomyia (Diptera: Psychodidae) with description of a new species from Lara. J Med Entomol. 1992;29:729–744. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/29.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sierra D, Velez ID, Uribe S. Identification of Lutzomyia spp. (Diptera: Psychodidae) Verrucarum group through electron microscopy of its eggs. Rev Biol Trop. 2002;48:615–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Escovar J, Ferro C, Cardenas E, Bello F. Karyotypic comparison of five species of Lutzomyia (Diptera: Psychodidae) of the series townsendi and the Verrucarum group in Colombia. Biomedica. 2002;22:499–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beati L, Caceres AG, Lee JA, Munstermann LE. Systematic relationships among Lutzomyia sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of Peru and Colombia based on the analysis of 12S and 28S ribosomal DNA sequences. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arrivillaga JC, Norris DE, Feliciangeli MD, Lanzaro GC. Phylogeography of the neotropical sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Infect Genet Evol. 2002;2:83–95. doi: 10.1016/s1567-1348(02)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohnstaedt LW, Gillen JI, Munstermann LE. Light-emitting diode technology improves insect trapping. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2008;24:331–334. doi: 10.2987/5619.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beati L, Keirans JE. Analysis of the systematic relationships among ticks of the genera Rhipicephalus and Boophilus (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial 12S ribosomal DNA gene sequences and morphological characters. Int J Parasitol. 2001;87:32–48. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0032:AOTSRA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar S, Nei M, Dudley J, Tamura K. MEGA: a biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief Bioinform. 2008;9:299–306. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozas J, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clement M, Posada D, Crandall KA. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol Ecol. 2000;9:1657–1659. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crozier RH, Crozier YC. The mitochondrial genome of the honeybee Apis Mellifera—complete sequence and genome organization. Genetics. 1993;133:97–117. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cywinska A, Hunter FF, Hebert PD. Identifying Canadian mosquito species through DNA barcodes. Med Vet Entomol. 2006;20:413–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2006.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcondes CB, Day JC, Ready PD. Introgression between Lutzomyia intermedia and both Lu. neivai and Lu. whitmani, and their roles as vectors of Leishmania braziliensis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:725–726. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukhopadhyay J, Ghosh K, Ferro C, Munstermann LE. Distribution of phlebotomine sand fly genotypes (Lutzomyia shannoni, Diptera: Psychodidae) across a highly heterogeneous landscape. J Med Entomol. 2001;38:260–267. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander JB. Dispersal of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) in a Colombian coffee plantation. J Med Entomol. 1987;24:552–558. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/24.5.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrison AC, Ferro C, Morales A, Tesh RB, Wilson ML. Dispersal of the sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae) at an endemic focus of visceral leishmaniasis in Colombia. J Med Entomol. 1993;30:427–435. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/30.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauzer LGSR, Souza NA, Maingon RDC, Peixoto AA. Lutzomyia longipalpis in Brazil: a complex or a single species? A mini-review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:1–12. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foley DH, Wilkerson RC, Cooper RD, Volovsek ME, Bryan JH. A molecular phylogeny of Anopheles annulipes (Diptera: Culicidae) sensu lato: the most species-rich anopheline complex. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;43:283–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mangabeira O. Sobre duas novas especies de Flebotomus (Diptera, Psychodidae) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1938;33:349–356. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Besansky NJ, Severson DW, Ferdig MT. DNA barcoding of parasites and invertebrate disease vectors: what you don't know can hurt you. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:545–546. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]