Abstract

The therapeutic efficacies of 3-day regimens of artesunate-amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine during 5 years of adoption as first-line treatments were evaluated in 811 ≤ 12-year-old malarious children. Compared with artemether-lumefantrine, amodiaquine-artesunate significantly reduced the proportion of children with fever and parasitemia 1 day after treatment (day 1; P < 0.008 for both). The proportion of parasitemic children on day 2 and gametocytemia on presentation and carriage reduced significantly over the years (P < 0.000001 and P < 0.03, respectively; test for trend). Overall efficacy was 96.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 94.5–98.6) and remained unchanged over the years (P = 0.87; test for trend). Kinetics of parasitemias after treatments were estimated by a non-compartmental model. Declines of parasitemias were monoexponential, with a mean elimination half-life of 1.09 hours (95% CI = 1.0–1.16). Parasitemia half-lives and efficacy were similar for both regimens and in all ages. Artesunate-amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine remain efficacious treatments of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Nigerian children 5 years after adoption.

Introduction

Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are now the first-line treatments of Plasmodium falciparum malaria globally; they are more effective than non-artemisinin–based combination or monotherapies, and they reduce the chances of development of drug resistance in P. falciparum.1,2 With the ready availability of copackaged ACTs and artemisinin and the adoption of ACTs as first-line treatments by over 50 endemic African countries,3,4 there is an increasing likelihood of artemisinin monotherapy, which may promote insensitivity and drug resistance in P. falciparum to ACTs. A recent report of resistance in P. falciparum to artemisinin in Southeast Asia5 has raised concerns that resistance may spread from this focus to other parts of the malaria-affected world, including Africa. Historically, the spread of antimalarial drug resistance in P. falciparum is from Southeast Asia or South America to East Africa and later, West Africa,6 where drug treatment failure is first encountered in < 5-year-old children because of a relative lack of antimalarial immunity. This makes it imperative to evaluate therapeutic and parasitological responses to antimalarial drugs first in this group if drug treatment failure or resistance were to be detected.7

Despite the large number of countries in Africa adopting ACTs, long-term assessment of efficacies of these drug combinations have been less frequently done after adoption. In addition, the report in West Africa of reduced in vitro sensitivity of P. falciparum isolates to artemisinin,8 the parent drug from which artesunate and artemether are derived, justifies the need for continuous assessment of in vivo and in vitro responses of P. falciparum isolates from this endemic area to ACTs. In view of the importance of detecting early changes in responses to ACT treatment before frank treatment failure occurs, we report a continuous evaluation of the in vivo efficacy in the 5 years (2005–2010) since policy change to two of the most frequently used ACTs in Africa—artemether-lumefantrine (AL) and artesunate-amodiaquine (AA)3,9,10—in an endemic area of southwest Nigeria. The primary aims were to determine if there are significant changes in the responses to ACTs over the years and if there are differences in the responses between the younger and older children that could be used as indicators of changes in the treatment responses to ACTs in endemic settings in Africa.

Methods

Study area.

The epidemiology of malaria in the area of study, Ibadan, southwest Nigeria, has been described elsewhere.11 Briefly, in this area of hyperendemic malaria, transmission occurs all year round but is more intense during the rainy season from April to October. P. falciparum is the predominant species, accounting for 99% of all infections. Children are more affected than adults, and apparently, asymptomatic infections occur in older school children and adults. Since 2005, the malaria clinic at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, has conducted five prospective randomized open-label controlled trials of artemisinin-based combination drugs in which artesunate-mefloquine (AM; one trial), AL (five trials), and AA (five trials) were the treatment arms. One non-comparative trial of artesunate drug efficacy was performed in children aged 0.5–12 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients enrolled in artemisinin-based combination therapies trials between 2005 and 2010 in Ibadan, southwest Nigeria

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trials | ||||||

| Artesunate-mefloquine (N = 174) | 174 | |||||

| Sinclair and others10 | ||||||

| Artesunate-amodiaquine (N = 486) | ||||||

| Sowunmi and others14 | 120 | |||||

| Gbotosho and others13 | 204 | |||||

| Sowunmi and others15 | 104 | |||||

| Unpublished* | 58 | |||||

| Artemether-lumefantrine (N = 325) | ||||||

| Sowunmi and others12 | 90 | |||||

| Gbotosho and others13 | 81 | |||||

| Sowunmi and others15 | 102 | |||||

| Unpublished* | 52 | |||||

| Subtotal (N = 985) | 210 | 174 | 206 | 285 | 110 | |

| Open trial for routine monitoring | ||||||

| Artesunate (N = 120) | 120 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sowunmi and others14 | ||||||

| Total (N = 1,105) | 330 | 0 | 174 | 206 | 285 | 110 |

Only in < 5 year olds.

In vivo studies of drug efficacy.

Study procedures.

Specific study procedures have been described for each trial.12–16 In addition, one recently controlled completed but unpublished trial has been included in the analysis. This involved comparison of AL and AA in < 5 year olds. All enrolment procedures were common to all studies. Briefly, patients were eligible to participate in the study if they were ≤ 12 years of age, had symptoms compatible with acute uncomplicated malaria such as anorexia, vomiting, or abdominal discomfort with or without diarrhea, P. falciparum parasitemia > 2,000 asexual forms/μL, a body (axillary) temperature > 37.4°C, or a history of fever in the 24–48 hours preceding presentation, had absence of other concomitant illness, had no history of antimalarial drug use in the 2 weeks preceding presentation, and had written informed consent given by parents or guardians. Patients with severe malaria,17 severe malnutrition, serious underlying diseases (renal, cardiac, or hepatic), and known allergy to study drugs were excluded from the study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health, Ibadan. The disease history, taken by the attending physician, was recorded by asking patients or their parents or guardians when the present symptomatic period started, and this was followed by a full physical examination by the same physician.

Drug regimens.

AL (Coartem; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) was given according to body weight: patients weighing 5–14 kg received one tablet, those weighing 14–24 kg received two tablets, those weighing 25–34 kg received three tablets, and those weighing more than 34 kg received four tablets at presentation (0 hours), 8 hours later, and 24, 36, 48, and 60 hours after the first dose. Each tablet of AL contains 20 mg artemether and 120 mg lumefantrine. AA coformulated (Coarsucam; Sanofi Aventis, Casablanca, Morocco) was given as follows: children weighing ≥ 9 –18 kg or aged 1–5 years received 0.5 tablets, children weighing ≥ 18–36 kg or aged 6–13 years received one tablet, and children weighing ≥ 36 kg or aged ≥ 14 years received two tablets. Each tablet of AA coformulated contains 270 mg amodiaquine base and 100 mg artesunate coformulated in a bilayer. AA copackaged (Dart; Swiss Pharma, Lagos, Nigeria) was given according to age or body weight as follows: 1–5 years or 5–15 kg received one tablet each of amodiaquine and artesunate, 6–10 years or 16–24 kg received two tablets each of amodiaquine and artesunate, and 11–15 years or 25–34 kg received three tablets each of amodiaquine and artesunate. Each tablet of amodiaquine contains 153 mg base, and each tablet of artesunate contains 50 mg in the copacked unit. All AA doses were given daily for 3 days. If necessary, patients were provided with antipyretics (paracetamol tablets, 10–15 mg/kg every 8 hours for 24 hours). Direct observed therapy was followed for all AA and AL doses.

The day of enrolment was regarded as day 0 (or 0 hours). Follow-up with clinical and parasitological evaluation was carried out at days 1–7 and days 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42. Follow-up consisted of enquiry about the patient's well-being, presence or absence of initial presenting symptoms, presence of additional symptoms, measurement of body temperature, measurement of heart and respiratory rates, and blood smear for the quantification of parasitemia.

Side effects were defined as symptoms and signs that first occurred or became worse after treatment was started. Any new events occurring during treatment were also considered as side effects.

Thick and thin blood films prepared from a finger prick were stained with Geimsa and examined by light microscopy under an oil-immersion objective at 1,000× magnification as previously described.12–15 Capillary blood collected before and during follow-up was used to measure packed cell volume (PCV) or hematocrit. Hematocrits were measured using a microhematocrit tube and microcentrifuge (Hawksley, Lancing, United Kingdom). Routine hematocrit was done on days 0–7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42. Blood was spotted on filter papers on days 0, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 and at the time of treatment failure for parasite genotyping.

Outcome measures.

Response to drug treatment was assessed using World Health Organization (WHO) 1973 and 2003 criteria4,5 as previously described.12–16 Parasite clearance time was defined as time from drug administration until there was no patent parasitemia for at least 48 hours. Fever clearance time was defined as time from drug administration until body temperature fell to or below 37.4°C and remained below this value for at least 48 hours. Recurrent infection was defined as the presence of asexual forms of P. falciparum from days 5 to 42. Recrudescent infections were differentiated from new infections using three-loci genotyping as previously described.18,19 Cure rates were defined as the percentages of patients whose asexual parasitemia cleared from peripheral blood and who were free of patent asexual parasitemia on days 28, 35, and 42 of follow-up. The cure rates on days 21–42 were adjusted on the basis of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping results of paired samples for patients with recurrent parasitemia after day 14 of commencing treatment.

Kinetics of parasitemia.

In 191 children enrolled between 2008 and 2009, follow-up with clinical and parasitological evaluation was done at the following times in all patients: 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hours and daily on days 2–7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42. The kinetics of the time course of the parasitemia were estimated by using a non-compartmental model as previously described.20

Relationship between enrolment parasite density and parasite clearance time.

The relationship between enrolment parasitemia and parasite clearance time was closely evaluated in 435 children enrolled between 2008 and 2009 in which parasite densities were measured at the following times: 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hours and daily on days 2–7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42.

Data analysis.

Data were analyzed using version 6 of the Epi-Info software21 and the statistical program SPSS for Windows version 10.01.22 Variables considered in the analysis were related to the densities of P. falciparum gametocytes and trophozoites. Proportions were compared by calculating χ2 with Yates' correction or by using Fisher exact test. Normally distributed continuous data were compared by Student t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data not conforming to a normal distribution were compared by the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests or by Wilcoxon ranked sum test. Prevalence rate of gametocyte on presentation and overall carriage rates were calculated yearly. Gametocyte carriages rates are presented as person-gametocyte weeks (PGW; number of weeks patients had gametocytes per number of weeks patients were followed-up) and are expressed per 1,000 weeks of follow-up. The cumulative risk of parasite reappearance was calculated by survival using the Kaplan–Meier method. Changes in prevalence and gametocyte carriage rates and the proportion of children remaining febrile and/or parasitemic on days 1–3 over the years were analyzed by χ2 test for trend. Association between enrolment parasite density and parasite clearance time was assessed by Pearson's correlation coefficient. All tests of significance were two-tailed. P values of ≤ 0.05 were taken to indicate significant differences. Data were double entered serially using the patients' codes and were only analyzed at the end of the study.

Results

The efficacies of AL and AA were evaluated in 811 of 985 children with uncomplicated P. falciparum infections enrolled in five ACT trials between 2005 and 2010 (Table1).

Of 486 children treated with AA, 158 received coformulated AA, and 328 received copackaged AA. The therapeutic responses of these children were similar; for example, for coformulated and copackaged AA-treated children, their parasite and fever clearance times were 1.03 ± 0.56 days versus 1.04 ± 0.51 days (P = 0. 89) and 1.0 ± 0.2 days (N = 140) versus 1.0 ± 0.3 days (N = 227; P = 1.0), respectively. Therefore, these data were combined.

The enrollment characteristics of the children are presented in Table 2. Overall, 35% (285 of 811) were children under 5 years, and 98% (N = 794) completed at least 28 days of follow-up. The main reason for not completing the 42-day follow-up was relocation from the study area. The drug combinations were generally well-tolerated, and no patient reported having serious adverse events.12–16 Three patients deteriorated within 2 hours of starting AA (N = 2) or AL (N = 1), becoming cerebral and requiring hospital admission. All recovered uneventfully. A 3-year-old girl who received AA died at home of causes unrelated to malaria or an adverse drug event. Autopsy was declined.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics at enrollment of children in artemisinin-based combination therapies efficacy trials between 2005 and 2010

| Variable | AA | AL | ALL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number enrolled | 486 | 325 | 811 |

| Number of males (%) | 249 (52.9) | 163 (50.4) | 412 (51) |

| Age (years) | 6.9 (3.2) | 5.9 (2.9) | 6.5 |

| Range | 0.67–12 | 0.7–12 | 0.67–12 |

| < 5 (%) | 144 (30) | 141 (43) | 285 (35) |

| ≥ 5 (%) | 342 (70) | 184 (57) | 526 (65) |

| Body temperature (°C) | 38.4 (1.1) | 38.4 (1.1) | 38.4 (1.1) |

| Range | 35.8–41.1 | 36–40.8 | 35.8–41.1 |

| Number > 37.4°C | 367 | 258 | 625 |

| Number > 40°C | 32 | 26 | 58 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 31.6 (4.3) | 30.5 (4.5) | 31.1 (4.4) |

| Range | 17–44 | 17–42 | 17–44 |

| Duration of illness (days) | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.3) |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum | 7 | 10 | 10 |

| GMPD (per μL blood) | 52,625 | 63,580 | 57,000 |

| Range | 2,160–2,124,000 | 2,837–1,183,145 | 2,160–2,124,000 |

| > 250,000 | 24 | 39 | 63 |

| GMGD (per μL blood) | 42 (N = 17) | 30 (N = 16) | 36 (N = 33) |

| Minimum | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Maximum | 450 | 366 | 450 |

AA = amodiaquine artesunate; AL = artemether-lumefantrine; GMPD = geometric mean gametocyte density.

Clinical and parasitological responses.

Changes in fever clearance times were evaluated in all patients who presented with fever (N = 625). Overall, 91% (568 of 625; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 91.07–91.12) of patients were afebrile by day 1, and the remainder were afebrile by day 2; this proportion decreased significantly with time (P = 0.003; test for trend) (Table 3). The proportions of children who remained febrile on day 1 were significantly lower in AA- than in AL-treated children (21 of 367 versus 3 of 258; P = 0.007).

Table 3.

Fever and parasite clearance time (in days) in children treated with AA or AL between 2005 and 2010

| Variable | 2005 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AL | AA | AL | AA | AL | AA | AL | |

| Fever clearance | ||||||||

| Number febrile on D0 (%) | 66 (100) | 79 (100) | 72 (100) | 66 (100) | 171 (100) | 61 (100) | 58 (100) | 52 (100) |

| Number febrile on D1 (%) | 5 (7.5) | 17 (22) | 6 (8.3) | 6 (9.1) | 10 (5.8) | 8 (13.1) | 0 | 5 (9.6) |

| Number febrile on D2 (%) | 0 | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.9) |

| Number febrile on D3 (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number febrile on D4 (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parasite clearance | ||||||||

| Number positive on D0 (%) | 120 (100) | 90 (100) | 104 (100) | 102 (100) | 204 (100) | 81 (100) | 58 (100) | 52 (100) |

| Number positive on D1 (%) | 34 (28.3) | 55 (61.1) | 23 (22) | 24 (24) | 15 (7.4) | 8 (9.8) | 4 (6.9) | 12 (23) |

| Number positive on D2 (%) | 11 (9.2) | 4 (4.4) | 1 | 5 (4.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number positive on D3 (%) | 1 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number positive on D4 (%) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

D = day.

In < 5 year olds and ≥ 5 year olds, the proportions of children who were afebrile on day 1 were 218 of 247 (88.3%) and 350 of 378 (92.3%), respectively (P = 0.09). Mean hematocrit on enrolment was 28.9% (95% CI = 28.3–29.4), and it increased significantly to 32.6% (95% CI = 31.9–33.3), 32.3% (95% CI = 31.7–32.9), and 30.7% (95% CI = 29.8–31.6) in 2006, 2009, and 2010, respectively (P < 0.0001). Mean hematocrit values were similar at all times in AA and AL treatment groups at enrollment over the years.

Parasite clearance times were available for all patients (Table 3), except one child treated with AA in whom parasitemia persisted for over 7 days after commencement of therapy. There was a significant decrease in the number of children failing to clear their parasitemias by day 2 over the years (P < 0.000001; test for trend). In 2005, 7.1% (15 of 210) were parasitemic by day 2 compared with 0.98% (6 of 601) between 2008 and 2010 (P = 0.000004). By day 3, 99.4% (806 of 811) of the children had cleared their parasitemias. The proportion of children with parasitemia on day 1 was significantly lower in AA- than AL-treated children (76 of 486 versus 99 of 325; P = 0.0000008).

In < 5 year olds and ≥ 5 year olds, the proportions of children who were parasitemic on day 1 were 68 of 285 (23.8%) and 107 of 526 (20.3%), respectively (P = 0.28). Of the 21 children with parasitemia on day 2, 8 and 13 children, respectively, were < 5 year olds and ≥ 5 year olds. The difference between these proportions was not significant (P = 0.95). All but one of five children with parasitemia on day 3 (Table 3) were ≥ 5 years.

Gametocyte carriage.

Overall, 4.1% (33 of 811) of children had patent gametocytemia at enrolment, and this proportion decreased from 8.1% (17 of 210) in 2005 to 3.6% (4 of 110) in 2010 (P = 0.02; test for trend), resulting in significant decrease in gametocyte carriage rates over the study period (P < 0.0001) (Table 4). Gametocyte prevalence on enrolment and carriage rates over the years were similar in AA- and AL-treated children.

Table 4.

Gametocyte prevalence rate at enrollment and gametocyte carriage rate (overall and among children without gametocytemia at enrollment)

| 2005 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 210 | 206 | 285 | 110 |

| Prevalence (%) | 17 (8.1%) | 4 (1.9%) | 9 (3.2%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Overall gametocyte carriage rate | ||||

| Person-weeks of follow-up | 1,050 | 1,236 | 1,710 | 550 |

| Gametocyte carriage (in weeks) | 14 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 1.2 |

| Gametocyte carriage rate (per 1,000 PGW) | 13 | 0.3 | 1 | 2 |

| Patients without gametocyte at enrollment | ||||

| Person-weeks of follow-up | 30 | 18 | 12 | – |

| Gametocyte carriage (in weeks) | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | – |

| Gametocyte carriage rate (per 1,000 PGW) | 46 | 44 | 42 | |

| Gametocytemia at enrollment | ||||

| Total number of patients | ||||

| AA | 120 | 104 | 204 | 58 |

| AL | 90 | 102 | 81 | 52 |

| Prevalence (%) | ||||

| AA | 11 (9.1%) | 4 (3.8%) | 6 (2.9%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| AL | 6 (6.7%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | 3 (5.8%) |

Parasitological efficacy.

Of the 29 recurrent infections during the 28- to 42-day follow-up, 11 (1.4%) were new infections, and 18 (2.2%) were recrudescent infections with P. falciparum. In two cases, the PCR result was inconclusive. The median time to recrudescence occurred at 21 days of follow-up (range = 15–42). The median time to reinfection was 21 days (range = 21–42). Recurrent infections were significantly more common in AL-treated children (21 of 325 versus 8 of 486; P = 0.0006). However, the proportion with recrudescent infections was similar (11 of 325 in AL and 7 of 486 in AA; P = 0.1). Of the seven recrudescent infections in children treated with AA, four were in those children who received the coformulation, and three were in those children who received the copackaged AA. Figure 1 is a Kaplan–Meier plot (survival curve) of the cumulative probability of reappearance of asexual parasitemia after treatment with AA or AL. The probability was significantly higher after AL treatment (log-rank statistic = 13.5; P < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plot (survival curve) of the cumulative probability of asexual parasitemia after treatment with AA (green, solid line) or AL (red, broken line; log-rank statistic = 13.5; P < 0.0001).

Of the 29 recurrent infections, 13 and 16 infections were in < 5 and > 5 year olds, respectively. The difference in proportions of children with recurrent infections was not significant (13 of 285 versus 16 of 526; P = 0.36). Of the recrudescent infections, 8 and 10 infections were in < 5 and > 5 year olds, respectively. The difference in proportions of children with recrudescent infections was also not significant (8 of 285 versus 10 of 526; P = 0.44).

Overall, non-PCR–adjusted parasitological efficacy was 96.5% (95% CI = 94.5–98.6) on day 28, it did not change over the years (P = 0.87; test for trend), and it was similar for both treatments (AA: 95.8%, 95% CI = 92.3–99.5; AL: 97.3%, 95% CI = 95.4–99.1). For both drugs, parasitological efficacy also did not change over the years (P = 0.15 for AA and P = 0.39 for AL; tests for trend for both).

Kinetics of parasitemia.

The demographic and other characteristics of the 191 children (N = 91 for AA and N = 100 for AL) enrolled in kinetics of the parasitemia study are shown in Table 5. Overall, there was monoexponential decline of the parasitemia, with an estimated mean half-life (t1/2el) of 1.09 hours (95% CI = 1.0–1.16) (Figure 2A). In < 5 (N = 54) and > 5 (N = 137) year olds, estimated mean t1/2el values were 0.98 hours (95% CI = 0.84–1.12) and 1.13 hours (95% CI = 1.02–1.23), and they were similar (P = 0.11) (Figure 2B). The estimated mean t1/2el values were also similar in AA- (1.12 hours, 95% CI = 1.0–1.24) and AL-treated (1.06 hours, 95% CI = 0.95–1.18) children (P = 0.53) (Figure 2B).

Table 5.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of children enrolled in kinetics of parasitemia study

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number enrolled | 191 |

| Number of males (%) | 89 (46) |

| Age (years) | 6.9 (2.9)* |

| Range | 0.67–13 |

| < 5 (%) | 54 (28.2) |

| Body temperature (°C) | 38.4 (1.1)* |

| Range | 36–41 |

| Number > 40°C (%) | 15 (7.8) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 32.6 (3.9)* |

| Range | 17–44 |

| < 30% (%) | 23 (12) |

| Duration of illness (days) | 2.5 (1.1)* |

| Minimum | 1 |

| Maximum | 7 |

| GMPD (per μL blood) | 85,326 |

| Range | 2,024–1,125,000 |

| > 250,000 | 29 |

| Fever clearance time (days)† | 1.0 (0.2)* |

| Range | 1–3 |

| 95% CI | 1.01–1.1 |

| Parasite clearance time (hours)‡ | 26.9 (13.5)* |

| Range | 8–96 |

| 95% CI | 24.9–28.8 |

Standard deviation.

Fever clearance times were 1.0 ± 0.1 versus 1.1 ± 0.3 days for AA and AL, respectively (P = 0.03).

Parasite clearance times were 26.2 ± 13.9 versus 27.5 ± 13.4 hours for AA and AL, respectively (P = 0.51).

Figure 2.

Semilog plots of parasitemia versus time (A) in all, < 5-year-old, and ≥ 5-year-old children treated with AA or AL and (B) in all children treated with either AA (dotted line) or AL (solid line).

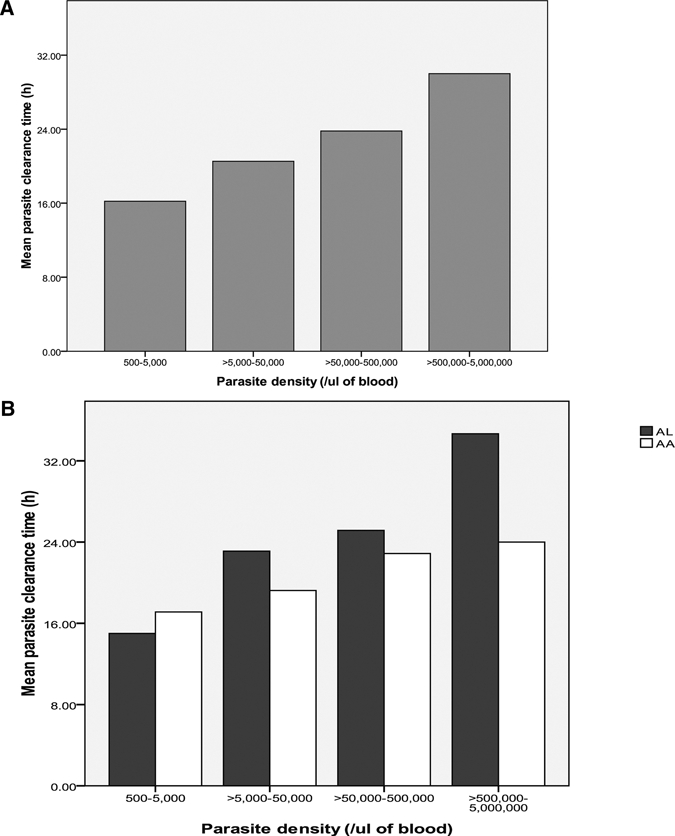

Relationship between enrolment parasite density and parasite clearance time.

Parasite clearance times were available in 744 children (92%) for evaluation of the relationship between enrolment parasite density and parasite clearance time. Overall, enrolment geometric mean parasitemia was significantly lower in children in whom parasitemia cleared by day 1 (24 hours; N = 575) compared with those in whom parasitemia cleared after day 1 (N = 169; 53,675/μL [95% CI = 48,549–59,343] versus 69,212/μL [95% CI = 58,362–82,079]; P = 0.015). Parasite clearance time was also significantly lower in patients with enrolment parasitemia < 100,000/μL (N = 510) compared with those with enrolment parasitemia ≥ 100,000/μL (N = 234; 1.09 days [95% CI = 1.04–1.14] versus 1.19 days [95% CI = 1.11–1.28]; P = 0.028). In 435 children in whom parasitemia was very closely monitored until clearance, parasite clearance time increased as parasitemia increased (Figure 3). In patients with enrolment parasitemia < 50,000/μ and ≥ 50,000/μL, the respective mean parasite clearance times were 20.1 (95% CI = 18.2–22.0) and 24.2 hours (95% CI = 22.5–25.9) (Figure 3A). The difference between the two values was significant (P = 0.003). This relationship was also maintained in patients treated with the individual AA or AL (Figure 3B). There was a significant positive correlation between enrolment parasite density and parasite clearance time (r = 0.13; P = 0.008).

Figure 3.

Relationship between enrolment parasite density and parasite clearance time in children treated with (A) AA and AL and (B) the individual drug combination.

Discussion

The rapid progression of resistance in the late 1990s and early 2000s in P. falciparum to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine,23–26 the first- and second-line treatments, respectively, of uncomplicated infections in Nigeria and the recommendation of the WHO1 led to the introduction and adoption, in mid-2005, of AL and AA as first-line antimalarials in Nigeria.27,28 With the adoption of these ACTs, small-scale studies have been frequent in the country,29,30 but evaluation of relatively large numbers of children over a relatively long period is an exception. The present study attempted to rectify this deficiency. Additionally, it evaluated the elimination half-lives of the parasitemias in children treated with AA and AL to establish a baseline against which the future behavior of these and other ACTs on the parasitemias may be compared.

The study showed that AA cleared fever and parasitemia significantly faster than AL in the 24 hours after administration. The former was expected, because the amodiaquine component of AA has a potent antipyretic effect.31 This antipyretic effect may be dose-dependent: a recent study from the area showed that children who received higher doses cleared parasitemia or fever significantly faster than children receiving the standard doses of AA.32

Rapid asexual parasite clearance is characteristic of all ACTs33 and the ACTs evaluated in the present cohort of children. Delay in parasite clearance (> 2 days) occurred in less than 0.7% of the children (Table 3). Because delay in parasite clearance is characteristic of resistance to artemisinin or ACTs2,34 and is associated with increased risk of gametocyte carriage, this low figure suggests full sensitivity of P. falciparum in vivo to ACTs in the area of study.35 In addition, the value is considerably below the threshold of 3% parasite positivity rate considered indicative of increased chance of recrudescence or resistance to artemisinins.36 Parasite positivity rate on day 3 also decreased insignificantly over the years (P = 0.09) (Table 3). Thus, there was a tendency to decreased chance of recrudescence over the years. The similar clearance rates and half-lives of parasitemia in younger (< 5 years) and older children suggest that clearance of parasites in these children is independent of immunity.

It is intriguing that parasitological efficiency remained unchanged over the years. The high parasitological efficiency with AA may be because of, among other factors, the decline in the use of chloroquine monotherapy37 and relatively little or no use of amodiaquine monotherapy in the study area before and even after ACTs adoption. This trend is in sharp contradistinction to the situation in Myanmar, where parasitological efficiency of AA is declining.38

The parasitemia half-life of 1 hour provides a baseline for which future changes in parasite population in vivo and in vitro susceptibility profiles from this endemic area may be measured or compared, and it may be relevant in the evolution of drug resistance to the adopted ACTs. With an overall parasitemia half-life of 1 hour, it would seem likely that genuine differences occur in the parasitemia kinetics after artemisinin or ACTs administration in children from this endemic area and in patients from Vietnam (8 hours)39 or Thailand (3 hours),35 where the half-lives of parasitemia are considerably longer than in the present study. These differences may be related to different sampling times, different pharmacokinetic models, population variations in drug handling, and regional differences in susceptibilities in P. falciparum isolates to artemisinins and the partner drugs36 in a region where recent data suggest that artemisinin resistance has developed.40–43

It would seem that enrolment parasitemia significantly influenced the parasite clearance times. Thus, high parasitemias were associated with a longer parasite clearance times. If recrudescence were to occur in the future, it would likely be in the latter.36 In conclusion, AA and AL remain efficacious treatments of falciparum malaria in Nigerian children, and significant drug resistance does not seem to have emerged after 5 years of adoption as first-line treatments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to our colleagues Drs. Folarin and Michael and our clinic staff, especially Ebunsola Oyetade, for assistance with running the study. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene assisted with publication expenses.

Footnotes

Authors' address: Grace O. Gbotosho, Akintunde Sowunmi, Christian T. Happi, and Titilope M. Okuboyejo, Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics and Institute for Medical Research and Training, University of Ibadan, Nigeria, E-mails: solagbotosho@yahoo.co.uk, akinsowunmi@hotmail.com, christianhappi@hotmail.com, and attitte@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Antimalarial Drug Combination Therapy. Report of a WHO Technical Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adjuik M, Babiker A, Garner P, Olliaro P, Taylor W, White N. Artesunate combinations for treatment of malaria: meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004;363:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15162-8. International Artemisinin Study Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosman A, Mendis KN. A major transition in malaria treatment: the adoption and deployment of artemisinin-based combination therapies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77((Suppl 6)):193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Facts on Artemisinin Based Combination Therapies. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. 2010. http://www.rollbackmalaria.org/cmc-upload/0/000/015/364/RBMInfosheet-9.htm Available at. Accessed December 7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Poravuth Y, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Lwin KM, Ariey F, Hanpithakpong W, Lee SJ, Ringwald P, Silamut K, Imwong M, Chotivanich K, Lim P, Herdman T, An SS, Yeung S, Singhasivanon P, Day NPJ, Lindegardh K, Socheat D, White NJ. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Chemotherapy of Malaria and Resistance to Antimalarials. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Assessment and Monitoring of Antimalarial Drug Efficacy for the Treatment of Uncomplicated Falciparum Malaria. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oduola AMJ, Sowunmi A, Milhous WK, Martin RK, Walker O, Salako LA. Innate resistance to new antimalarial drugs in Plasmodium falciparum from Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:123–126. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90533-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adjuik M, Agnamey P, Babiker A, Borrmann S, Brasseur P, Cisse M, Cobelens F, Diallo S, Faucher JF, Garner P, Gikunda S, Kremsner PG, Krishna S, Lell B, Loolpapit M, Matsiegui PB, Missinou MA, Mwanza J, Ntoumi F, Olliaro P, Osimbo P, Rezbach P, Some E, Taylor WRJ. Amodiaquine-artesunate versus amodiaquine for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in African children: a randomized, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinclair D, Zani B, Donegan S, Olliaro P, Garner P. Artemisinin-based combination therapy for treating uncomplicated malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD007483. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007483.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salako LA, Ajayi FO, Sowunmi A, Walker O. Malaria in Nigeria: a revisit. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1990;84:435–445. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1990.11812493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sowunmi A, Gbotosho GO, Happi CT, Adedeji AA, Fehintola FA, Folarin OA, Tambo E, Fateye BA. Therapeutic efficacy and effects of artemether-lumefantrine and amodiaquine-sulfalene-pyrimethamine on gametocyte carriage in children with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in southwestern Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gbotosho GO, Sowunmi A, Okuboyejo TM, Happi CT, Folarin OO, Michael SO, Adewoye EO. Therapeutic efficacy and effects of artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-amodiaquine co-formulated or co-packaged, on malaria-associated anemia in children with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in southwest Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:813–819. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sowunmi A, Balogun T, Gbotosho GO, Happi CT, Adedeji AA, Fehintola FA. Activities of amodiaquine, artesunate, and artesunate-amodiaquine against asexual- and sexual-stage parasites in falciparum malaria in children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1694–1699. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00077-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sowunmi A, Gbotosho GO, Happi C, Okuboyejo T, Folarin O, Balogun S, Michael O. Therapeutic efficacy and effects of artesunate-mefloquine and mefloquine alone on malaria-associated anemia in children with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in southwest Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:979–986. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michael OS, Gbotosho GO, Folatin OA, Okuboyejo T, Sowunmi A, Oduola AMJ. Early variation in Plasmodium falciparum dynamics in Nigerian children after treatment with two artemisinin-based combinations: implications on delayed parasite clearance. Malar J. 2010;9:335. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94((Suppl 1)):1–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, Sowunmi A, Hudson T, O'Neil M, Milhous W, Wirth DF, Oduola AMJ. Selection of Plasmodium falciparum multi-drug resistance gene 1 alleles in asexual stages and gametocytes by artemether-lumefantrine in Nigerian children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:888–895. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00968-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, Bolaji OM, Sowunmi A, Kyle DE, Milhous W, Wirth DF, Oduola AMJ. Association between mutations in Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter and P. falciparum multidrug resistance 1 genes and in vivo amodiaquine resistance in P. falciparum malaria-infected children in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sowunmi A, Falade AG, Adedeji AA, Ayede AI, Fateye BA, Sowunmi CO, Oduola AMJ. Comparative Plasmodium falciparum kinetics during treatment with amodiaquine and chloroquine in children. Clin Drug Investig. 2001;21:371–381. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anonymous . Epi Info Version 6. A Word Processing Data Base and Statistics Program for Public Health on IBM-Compatible Microcomputers. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anonymous . SPSS for Windows Release 10.01 (Standard Version) Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Falade CO, Akinboye DO, Gerena L, Hudson T, Sowunmi A, Kyle DE, Milhous W, Wirth DF, Oduola AMJ. Point mutation in the pfcrt and pfmdr-1 genes of Plasmodium falciparum and clinical response to chloroquine among malaria patients from Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97:439–451. doi: 10.1179/000349803235002489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Happi TC, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, Akinboye DO, Yusuf BO, Ebong OO, Sowunmi A, Kyle DE, Milhous W, Wirth DF, Oduola AMJ. Polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum dhfr and dhps genes and age related in vivo sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine-pyrimethamine resistance in malaria-infected patients from Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2005;95:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sowunmi A, Fateye BA, Adedeji AA, Fehintola FA, Gbotosho GO, Happi TC, Tambo E, Oduola AMJ. Predictors of the failure of treatment with chloroquine in children with acute, uncomplicated, Plasmodium falciparum malaria, in an area with high and increasing incidences of chloroquine resistance. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005;99:535–544. doi: 10.1179/136485905X51382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sowunmi A, Fateye BA, Adedeji AA, Gbotosho GO, Happi TC, Bamgboye AE, Bolaji OM, Oduola AMJ. Predictors of the failure of treatment with pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine in children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Acta Trop. 2006;98:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Federal Ministry of Health . National Malaria Treatment Policy. Abuja, Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Federal Ministry of Health . National Antimalarial Treatment Guidelines. Abuja, Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meremikwu A, Alaribe A, Ejemot R, Oyo-Ita A, Ekenjoku J, Nwachukwu C, Ordu D, Ezedinachi E. Artemether-lumefantrine versus artesunate plus amodiaquine for treating uncomplicated childhood malaria in Nigeria: randomized controlled trial. Malar J. 2006;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falade CO, Ogundele AO, Yusuf BO, Ademowo OG, Ladipo SM. High efficacy of two artemisinin-based combinations (artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate plus amodiaquine) for acute uncomplicated malaria in Ibadan, Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:635–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olliaro P, Mussano P. Amodiaquine for treating malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD000016. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gbotosho GO, Sowunmi A, Okuboyejo TM, Happi CT, Folarin OO, Adewoye EO. A simple dose regimen of artesunate-amodiaquine based on age or body weight range for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in children: comparison of therapeutic efficacy with standard dose regimen of artesunate-amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine. Am J Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e318209e031. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e318209e031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White NJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of artemisinin and derivatives. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88((Suppl 1)):S41–S43. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carrara VI, Zwang J, Ashley AA, Price RN, Stepniewska K, Brends M, Brockman A, Anderson T, McGready R, Phaiphun L, Proux S, van Vugt M, Hutagalung R, Lwin KM, Phyo AP, Preechapornkul P, Imwong M, Pukrittayakamee S, Singhasivanon P, White NJ, Nosten F. Changes in the treatment responses to artesunate-mefloquine on the northwestern border of Thailand during 13 years of continuous deployment. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sowunmi A, Adewoye EO, Gbotosho GO, Happi CT, Sijuade A, Folarion OA, Okuboyejo TM, Michael OS. Factors contributing to delay in parasite clearance in uncomplicated falciparum malaria in children. Malar J. 2010;9:53. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stepniewska A, Ashley A, Lee SJ, Anstey N, Barnes KI, Binh TQ, D'Alessandro U, day NPJ, de Vries PJ, Dorsey G, Guthmann J-P, Mayxay M, Newton PN, Olliaro P, Osorio L, Price RN, Rowland M, Smithuis F, Taylor WRJ, Nosten F, White NJ. In vivo parasitological measures of artemisinin susceptibility. J Inf Dis. 2010;201:570–579. doi: 10.1086/650301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mokuolu OA, Okoro EO, Ayetoro SO, Adewara AA. Effect of artemisinin-based treatment policy on consumption pattern of antimalarials. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smithuis F, Kyaw MK, Phe O, Win T, Aung PP, Oo AP, Naing AL, Nyo MY, Myint NZ, Imwong M, Ashley E, Lee SJ, White NJ. Effectiveness of five artemisinin combination regimens with or without primaquine in uncomplicated falciparum malaria: an open-label randomized trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:673–683. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70187-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Vries JP, Bich NN, Thien HV, Hung LN, Anh TK, Kager PA, Hiesterkamp SH. Combinations of artemisinin and quinine for uncomplicated falciaprum malaria: efficacy and pharmacodynamics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1302–1308. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.5.1302-1308.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wongsrichanalai C, Meshnick SR. Declining artesunate-mefloquine efficacy against falciparum malaria on the Cambodia-Thailand border. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:716–719. doi: 10.3201/eid1405.071601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, Smith BL, Socheat D, Fukuda MM. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2619–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim P, Alker AP, Khim N, Shah NK, Incardona S, Doung S, Yi P, Bouth DM, Bouchier C, Puijalon OM, Meshnick SR, Wongrichanalai C, Fandeur T, Le Bras J, Ringwald P, Ariey F. Pfmdr 1 copy number and artemisinin derivatives combination therapy failure in falciparum malaria in Cambodia. Malar J. 2009;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noedl H, Se Y, Sriwichai S, Schaecher K, Teja-Isavadharm P, Smith B, Rutvisuttinunt W, Bethell D, Surasri S, Fukuda MM, Socheat D, Chan Thap L. Artemisinin resistance in Cambodia: a clinical trial designed to address an emerging problem in Southeast Asia. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:e82–e89. doi: 10.1086/657120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]