Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to determine chiropractic patients' perceptions of chiropractors serving as primary care providers and having a limited prescriptive authority.

Methods

Four doctors of chiropractic in Albuquerque and Santa Fe, NM, participated in surveying their patients during the summer of 2008. The chiropractors distributed the questionnaires consecutively to chiropractic patients. Patients answered questions regarding their perceptions of their chiropractors, use of chiropractic care, and medications for pain. The participating chiropractors collected the completed patient questionnaires and mailed them to the primary investigator.

Results

The chiropractic providers collected 275 chiropractic patient questionnaires. The number of patient questionnaires collected by each of the 4 participating chiropractors ranged from 35 to 100. The patients primarily sought care for the management and treatment of pain (98.5%), and 57.5% considered that their chiropractors were “primary care providers.” Eighty-five percent preferred that their chiropractor be qualified to prescribe medications and provide hands-on treatment, whereas 97.5% perceived their chiropractors to be chiropractic physicians.

Conclusions

This small group of chiropractic patients from 4 offices in New Mexico perceived that their doctors of chiropractic were physicians and primary care providers, and 85% preferred that their chiropractor treat patients with limited prescriptive authority when appropriately trained.

Key indexing terms: Chiropractic, Primary care provider, Prescriptions, Patients, Integrative medicine

Introduction

America is experiencing a shortage in adult primary care, whereas medical students prefer higher-paying specialties as evidenced by a 58% reduction in residency positions offered in 2009 compared with one decade earlier.1 Primary care in the United States needs a lifeline.2 Interestingly, the editor the Journal of the American Medical Association suggested that doctors of chiropractic could be an option to solve the primary care crisis if they were to provide primary care.3

The Council on Chiropractic Education advises chiropractic schools to educate and train students to become competent doctors of chiropractic who will provide quality patient care and serve as primary care physicians.4 Chiropractors have an interest in providing primary care and claim to be qualified to perform the functions of a primary care provider.5,6 The Connecticut Chiropractic Association concluded that the chiropractic physicians licensed in Connecticut qualify to provide primary care services based upon the results of a survey of chiropractic college presidents, chiropractic organization leaders, and Connecticut-licensed doctors of chiropractic.7

The purpose of this study was to survey chiropractic patients in New Mexico on their perceptions about chiropractors being physicians and primary care providers and if the patients perceived that chiropractors should be trained to treat patients with a limited prescriptive authority and hands-on treatment to control pain.

Methods

An attitude survey instrument was first developed and then tested in one New Mexico chiropractic office. The primary investigator distributed 47 questionnaires to chiropractic patients; then a panel of chiropractic providers and staff from 3 different offices studied the survey responses. Three of the 6 questions were confusing to both providers and patients. After rewriting the problematic questions, the panel reached consensus and approved the 6 questions before distribution to the participating chiropractors. The research complied with the Helsinki Declaration.

The New Mexico Chiropractic Association (NMCA) distributed the e-mail invitations to participate in the research project to 62 members with registered e-mail addresses. Only 10 NMCA members responded to the invitation. They received the survey instrument via e-mail from the NMCA.

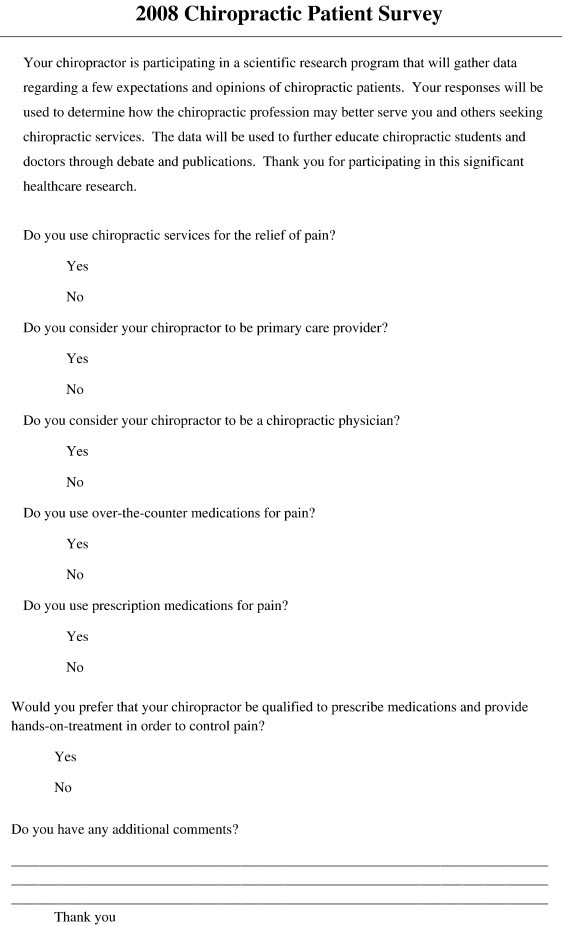

The chiropractors distributed the questionnaires consecutively to chiropractic patients. Patients answered questions regarding their perceptions of their chiropractors, use of chiropractic care, and medications for pain. The participating chiropractors collected the completed patient questionnaires and mailed them to the primary investigator (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Survey used in this study.

The University of Bridgeport Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study. The University of Bridgeport Institutional Review Board operates under Code of Federal Regulations CFR: Title 45, Part 46. This project did not receive funding from any source.

Results

We invited a total population of 62 NMCA chiropractors to participate in this study. During the data collection, one of the participating chiropractors collected a modified questionnaire and collected these modified questionnaires from 6 respondents. Consequently, those questionnaires were invalidated. Ten chiropractors responded (16% response rate), and 4 were considered valid responders (10% valid response rate). The valid responders collected 275 questionnaires (69% response rate questionnaires; Table 1). The 275 valid questionnaires were from 4 different chiropractic providers in Albuquerque and Santa Fe.

Table 1.

Chiropractic patient survey results (N = 275)

| Question | Yes | No | Response rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you use chiropractic services for the relief of pain? | 271 (98.5%) | 4 (1.5%) | 100% |

| Do you consider your chiropractor to be a primary care provider? | 159 (57.8%) | 116 (42.2%) | 100% |

| Do you consider your chiropractor to be a chiropractic physician? | 268 (97.5%) | 7 (2.5%) | 100% |

| Do you use over-the-counter medications for pain? | 206 (74.9%) | 69 (25.1%) | 100% |

| Do you use prescription medications for pain? | 84 (30.5%) | 191 (69.5%) | 100% |

| Would you prefer that your chiropractor be qualified to prescribe medications and provide hands-on-treatment in order to control pain? | 234 (85.1%) | 41 (14.9%) | 100% |

The study revealed that a group of 275 chiropractic patients received care for the relief of pain and preferred their chiropractors to have the ability to prescribe medications. These patients considered their chiropractors to be chiropractic physicians and primary care providers. These chiropractic patients also used both over-the-counter and prescription medications for the management of their pain.

The patient responses from all 4 chiropractors were similar in spite of the chiropractic school attended and enrollment in the advanced practice program. The participating chiropractors attended and graduated from 4 different institutions including Palmer College of Chiropractic (West), Palmer College of Chiropractic (Davenport), Southern California University of Health Sciences, and Life University School of Chiropractic (Marietta).

Discussion

We wonder if chiropractic college administrators, practicing chiropractors, chiropractic-licensing boards, managed care organizations, and government officials consider the preferences of chiropractic patients to be of value. If chiropractic patients prefer their chiropractors to have limited prescription rights, will the profession expand the scope of chiropractic therapeutic services to include a limited prescriptive authority? Previous community studies demonstrated that chiropractors, consumers, and the allopathic community might be indifferent to the idea of chiropractors and other nonmedical doctors as major primary care providers.8 An HMO experiment in New Mexico demonstrated that many physicians have little or no objection to receiving a competent and personable chiropractor as their professional colleague and that patients like the seamless aspects of having chiropractors and physicians in the same health care system.9 The University of New Mexico also showed that medical doctors and chiropractors can practice side by side. The School of Medicine has credentialed chiropractors as Clinical Assistant Professors in Internal Medicine since 2002 to serve as clinical preceptors for senior medical students.10

Primary care practitioner

In New Mexico, primary care practitioner means a health care professional who, within the scope of his or her license, supervises, coordinates, and provides initial and basic care to covered persons; who initiates their referral for specialist care; and who maintains continuity of patient care. Primary care practitioners shall include but not be limited to general practitioners, family practice physicians, internists, pediatricians, and obstetricians-gynecologists, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. Pursuant to 13.10.21.7 New Mexico Administrative Code (NMAC), other health care professionals may also provide primary care. In 1998, the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission, Division of Insurance, issued the following scope to all managed care companies with the issuance of rule 13.10.13. This scope permits chiropractic physicians to contract with managed care companies as physicians and provide primary care services. This rule applies to health care insurers that are required to obtain a certificate of authority or licensure in this state and that provide, offer, or administer managed health care plans (MHCPs). Nothing contained in this section or contained in the definition of primary care physician shall preclude other health care professionals such as doctors of oriental medicine, chiropractic physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or certified nurse midwives from providing primary care provided that the health care professional (1) is acting within his or her scope of practice as defined under the relevant state licensing law, (2) meets the MHCP eligibility criteria for health care professionals who provide primary care, and (3) agrees to participate and to comply with the health care insurers or MHCPs care coordination and referral policies.11

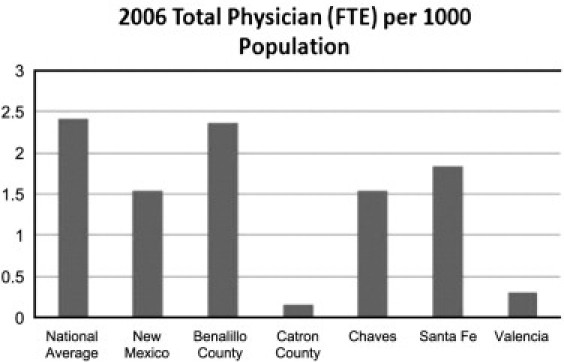

Physician shortage

A shortage, for decades, of both allopathic and osteopathic physicians in New Mexico has been well documented and publicized. The following excerpt from the New Mexico Health Policy Commission, “Long History of Being a Physician Shortage,” is indicative of public statements on the need for more physicians in the state (Fig 2).12

Fig 2.

Physician full time equivalents (FTE) for selected locations in New Mexico.

Chiropractic limited prescriptive authority

According to current New Mexico state statute 61-4-9.1 (C) New Mexico Statutes Annotated (NMSA), chiropractic physicians can seek requisite training for credentials that permit limited prescriptive authority.

A chiropractic physician shall have the prescriptive authority to administer through injection and prescribe the compounding of substances that are authorized in the advanced practice formulary. Those with active registration are allowed prescription authority that is limited to the current formulary as agreed on by the New Mexico board of chiropractic examiners and as by statute, by the New Mexico board of pharmacy and the New Mexico medical board.13

Educational training for chiropractic physicians

As with any consideration of the expansion of scope of practice, education and training are a concern. At present, there are some institutions who are considering expanding the education and training for chiropractic physicians. The National University of Health Sciences in Chicago, IL, is presently providing primary care training to chiropractic physicians in New Mexico seeking the status of a chiropractic physician.14 This program is a 2-year Master's Degree in Advanced Practice and qualifies the credentialed chiropractor to practice as a primary care provider according to the New Mexico Managed Care Regulations. In addition, this advanced clinical training permits the credentialed chiropractic physician to practice with an expanded scope of practice that includes a prescriptive authority, allowing the advanced chiropractic physician to serve as a primary care physician in New Mexico.

Limitations of study

There are many limitations to this study. Only 4 of the 62 members of the NMCA participated. As well, there are other chiropractors in New Mexico who are not members of the NMCA; therefore, this study is not representative of all chiropractic practices and their patients in the state of New Mexico. As well, the small sample size of patients decreases the accuracy and validity of the study. Because the patients surveyed were only from 4 practices, it is likely that there was selection bias. Three of the 4 chiropractors intended to become advanced practice chiropractors; therefore, it is possible that this is not a representative sample of chiropractic offices and patients in New Mexico. The patients may have self-selected to practices that were in favor of chiropractic as primary care and use of limited prescription privileges. Another limitation is that the terms used in the survey were not defined (eg, physician and primary care provider); thus, some patients may have responded differently if the definitions were present. As this study only surveyed patient perceptions, no conclusions can be made in regard to safety and effectiveness of an expanded scope of practice, as that would need to be accomplished by a different study.

There was a compromise of the data quality due to a lack of control during the collection process, invalidating the majority of the data. The few number of observations lessens the generalizability. The potential for biased interviewers threatened the reliability of the data. The questions may have been leading, and one included a combined response (ie, if chiropractors should both prescribe and use hands-on therapy to control pain); thus, patient responses and findings may have been different if the questions were formatted more clearly. The use of dichotomous, closed-ended questions simplified the survey instrument; however, it minimized the assessment values of the patients' perceptions. These limitations should be taken into consideration in future studies.

Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that a majority of a select group of 275 chiropractic patients in New Mexico sought chiropractic care for pain. Of the patients who participated, 85% responded that they would prefer that their doctor of chiropractic “be qualified to prescribe medications and provide hands-on-treatment in order to control pain.” We recommend follow-up studies in New Mexico and other geographic locations with the selection of a larger representation of patients and practices.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

References

- 1.Steinbrook R. Easing the shortage in adult primary care—is it all about money? N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2696–2699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0903460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodenheimer T., Grumbach K., Berenson R.A. A lifeline for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693–2696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundberg G.D., Lamm R.D. Solving our primary care crisis by retraining specialists to gain specific primary care competencies. JAMA. 1993;270:380–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Council on Chiropractic Education Standards for doctor of chiropractic programs and requirements for institutional standards. 2007. http://www.cce-usa.org/uploads/2007_January_STANDARDS.pdf VI. [Cited May 24, 2010]. Available from:

- 5.Cambron J.A., Cramer G.D., Winterstein J. Patient perceptions of chiropractic treatment for primary care disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kremer R.G., Duenas R., McGuckin B. Defining primary care and the chiropractic physicians' role in the evolving health care system. J Chiropr Med. 2002;1(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60021-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duenas R., Carucci G.M., Funk M.F., Gurney M.W. Chiropractic-primary care, neuromusculoskeletal care, or musculoskeletal care? Results of a survey of chiropractic college presidents, chiropractic organization leaders, and Connecticut-licensed doctors of chiropractic. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26(8):510–523. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(03)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teitelbaum M. The role of chiropractic in primary care: findings of four community studies. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23(9):601–609. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2000.110945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasternak D.P., Lehman J.J., Smith H.L., Piland N.F. Can medicine and chiropractic practice side-by-side? Implications for healthcare delivery. Hosp Top. 1999;77(2):8–17. doi: 10.1080/00185869909596520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.University of New Mexico/School of Medicine Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Integrative Medicine Center for Life. http://hsc.unm.edu/som/cfl/ [Cited May 28, 2010]. Available from:

- 11.Title 13 Insurance, Chapter 10 Health Insurance, Part 13 Managed Health Care-Benefits, 7, Definitions, V-Primary Care Practitioner. http://www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/NMAC/parts/title13/13.010.0013.htm 13.10.21.7 NMAC. [Cited May 28, 2010]. Available from:

- 12.New Mexico Health Policy Commission “Physician supply in NM 2006,” printed December 2007. http://www.aamc.org/workforce/recentworkforcestudies.pdf [Cited May 28, 2010]. Available from:

- 13.Title 16 Occupational and Professional Licensing, Chapter 4 Chiropractic Practitioners, Part 15 Chiropractic Advanced Practice Certification Registry, 8 Advanced Practice Registry General Provisions. http://www.nmcpr.state.nm.us/NMAC/parts/title16/16.004.0015.pdf 16.4.15.8. NMAC. [Cited May 28, 2010]. Available from:

- 14.National University of Health Sciences. Master of Science Advanced Clinical Practice. An advanced degree for the chiropractic profession. [Cited May 28, 2010] http://www.nuhs.edu/show.asp?durki=1233 Available from: