Abstract

In higher eukaryotes, the DNA composition of centromeres displays a high degree of variation, even between chromosomes of a single species. However, the long-range organization of centromeric DNA apparently follows similar structural rules. In our study, a comparative analysis of the DNA at centromeric regions of Beta species, including cultivated and wild beets, was performed using a set of repetitive DNA sequences. Our results show that these regions in Beta genomes have a complex structure and consist of variable repetitive sequences, including satellite DNA, Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons, and microsatellites. Based on their molecular characterization and chromosomal distribution determined by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), centromeric repeated DNA sequences were grouped into three classes. By high-resolution multicolor-FISH on pachytene chromosomes and extended DNA fibers we analyzed the long-range organization of centromeric DNA sequences, leading to a structural model of a centromeric region of the wild beet species Beta procumbens. The chromosomal mutants PRO1 and PAT2 contain a single wild beet minichromosome with centromere activity and provide, together with cloned centromeric DNA sequences, an experimental system toward the molecular isolation of individual plant centromeres. In particular, FISH to extended DNA fibers of the PRO1 minichromosome and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of large restriction fragments enabled estimations of the array size, interspersion patterns, and higher order organization of these centromere-associated satellite families. Regarding the overall structure, Beta centromeric regions show similarities to their counterparts in the few animal and plant species in which centromeres have been analyzed in detail.

[The sequence data described in this paper have been submitted to the EMBL data library under accession nos. AJ278751, AJ278752, and AJ243337.

Centromeres are the most prominent domains in eukaryotic chromosomes. These specialized domains can often be identified as primary constrictions or heterochromatic blocks in mitotic and meiotic chromosomes. They ensure cohesion of sister chromatids and serve as assembly sites for kinetochore proteins, which are necessary for spindle microtubule binding, facilitating faithful segregation of chromosomes to daughter nuclei. Although the functional aspect of centromeres is clearly defined, the composition and molecular organization of centromeric DNA is still poorly understood.

Initial studies fueled hopes that a functional centromere is represented by a clonable piece of DNA with a well-conserved consensus sequence. In fact, in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae a fully functional centromere is contained within a stretch of 125 bp. This minimal centromere consists of three well-characterized elements (CDE I, CDE II, CDE III) and is flanked by DNA packed into arrays of highly ordered nucleosomes (Clarke and Carbon 1980; Clarke 1990). However, this point centromere might represent an exception; most higher eukaryotes that have been examined so far have regional centromeres that can extend up to several megabase pairs in size.

An elegant study in Drosophila melanogaster showed that a 420-kb region in the X-chromosome-derived Dp1187 minichromosome is sufficient for full centromeric function in vivo (Murphy and Karpen 1995; Sun et al. 1997). This region consists predominantly of tandem arrays of conserved simple satellite repeats and few interspersed retrotransposon-like elements, and it is accompanied by a 200-kb flanking region that is composed of another satellite motif. Deletions in this region result in a significant decrease of meiotic and mitotic stability of the minichromosome, which is a good indication of an essential function of these repeated elements. However, neither the two simple satellites nor the interspersed retrotransposons are exclusively restricted to centromeres, but are also found in the heterochromatic regions outside the cytologically visible centromeres. To make the situation even more complex, these DNA sequences are not present on all D. melanogaster centromeres. The conclusion from these results is that centromeres, at least in Drosophila, show a much higher degree of variability than was initially anticipated and that epigenetic factors might contribute to centromere formation as well (Karpen and Allshire 1997; Sun et al. 1997).

In human, the most prominent repetitive DNA is the α-satellite DNA, a 171-bp monomer that is organized as tandem repeats at all centromeres (Willard and Waye 1987). It appears that the α-satellite DNA is important for proper centromere activity, although it remains unclear whether the satellites themselves or other interspersed sequences facilitate this function or if the satellites just provide a suitable structural environment for centromere formation.

In contrast to the extensive studies on the centromeric regions of yeast, Drosophila, and human, information on the structure of plant centromeres is still limited (Clarke 1990; Harrington et al. 1997; Sun et al. 1997). A very high proportion of plant nuclear genomes consists of repetitive DNA, such as satellites, microsatellites, and different types of retroelements. Using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) satellites with monomer lengths of 150–180 bp, hence resembling the human α-satellite repeat, and retrotransposon-like elements have been physically mapped on chromosomes of numerous plants and often account for most of the centromeric heterochromatin (Kamm et al. 1994; Harrison and Heslop-Harrison 1995; Kamm et al. 1995; Jiang et al. 1996b; Dong et al. 1998; Kubis et al. 1998). From a functional point of view, the centromere of a maize supernumerary B chromosome is best characterized showing also the repeated nature of the DNA at plant centromeres (Alfenito and Birchler 1993). These analyses showed that the B-chromosome centromere can be divided into distinct functional parts of a few hundred kilobases (Kászas and Birchler 1996, 1998).

Extensive studies based on genome sequencing and genetic mapping revealed the positions and large-scale molecular organization of the centromeric heterochromatic regions of Arabidopsis thalianachromosomes 2 and 4 (Round et al. 1997; Arabidopsis Genome Sequencing Consortium 1999; Copenhaver and Preuss 1999; Copenhaver et al. 1999; Lin et al. 1999). The centromeric regions are mainly composed of several types of middle-repetitive DNA that flank long arrays of a previously identified 180-bp satellite repeat (Martinez-Zapater et al. 1986; Simoens et al. 1988; Maluszynska and Heslop-Harrison 1991; Brandes et al. 1997; Heslop-Harrison et al. 1999). These studies revealed a high variability between individual centromeres, which differ not only in their chromosomal position but also in their size and DNA composition. Nevertheless, they also showed similarities in the organization of centromeres in higher eukaryotes. It is now becoming clear that variability is a characteristic feature of centromeric DNA, which makes it necessary to investigate these chromosomal domains in other plant species (Richards and Dawe 1998).

The genus Beta consists of the sections Beta, Corollinae, Nanae, and Procumbentes, and represents a group of closely and more distantly related species. A well-known member of the genus Beta is the sugar beet Beta vulgaris, a plant with a relatively small genome of 758 Mbp (Arumuganathan and Earle 1991). Many families of repetitive DNA, including >13 families of nonhomologous satellites and interspersed repeats, in addition to long terminal repeat (LTR) and non-LTR retrotransposons, have been identified in B. vulgaris and its wild relatives (Kubis et al. 1998). These repeat families have been extensively characterized at the molecular level and, together with high-resolution FISH, led to a structural model of a plant chromosome (Schmidt and Heslop-Harrison 1998). According to this model, large regions of repetitive DNA, mostly consisting of tandemly arranged satellite repeats and interspersed retrotransposons, are found at characteristic sites of the chromosome.

In this study, we focus on the centromeric region as one of these distinct domains of Beta chromosomes and analyze the long-range organization of major repetitive DNA families. Together with chromosomal mutants in B. vulgaris, which contain an additional acrocentric fragment from B. procumbens with centromere activity that resembles a plant minichromosome, these repetitive elements provide an experimental system for the molecular analysis of the structural organization of a genetically isolated plant centromere.

RESULTS

Major Sequence Classes at Centromeres of Beta Chromosomes

Here we report the physical mapping of repetitive sequences, including retrotransposon-like sequences, satellites, and microsatellites, that account for a large proportion of the centromeric heterochromatin in Beta species.

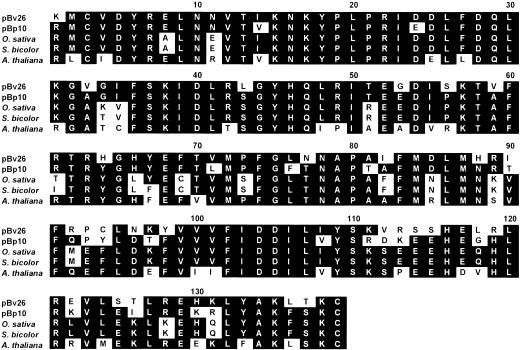

Using a pair of degenerated oligonucleotide primers for a conserved domain of retrotransposons (Friesen et al. 2001) we amplified two 417-bp fragments from B. vulgaris and B. procumbens. A BLAST search in GenBank with the DNA sequences of the cloned PCR products, named pBv26 (AJ278751) and pBp10 (AJ278752), revealed high homology with the reverse transcriptase gene of Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons (Fig. 1). The two fragments share 71% homology at the DNA level and contain a continuous open reading frame with 74% identity.

Figure 1.

Homology of plant Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons. Predicted amino acid sequences of reverse transcriptase domains of Beta vulgaris (pBv26), B. procumbens (pBp10), Oryza sativa(EMBL accession no. AF111709), Sorghum bicolor (accession no. BAA95869), Arabidopsis thaliana (accession no. AAF67363). Homologous amino acids that are conserved in at least two sequences are shaded.

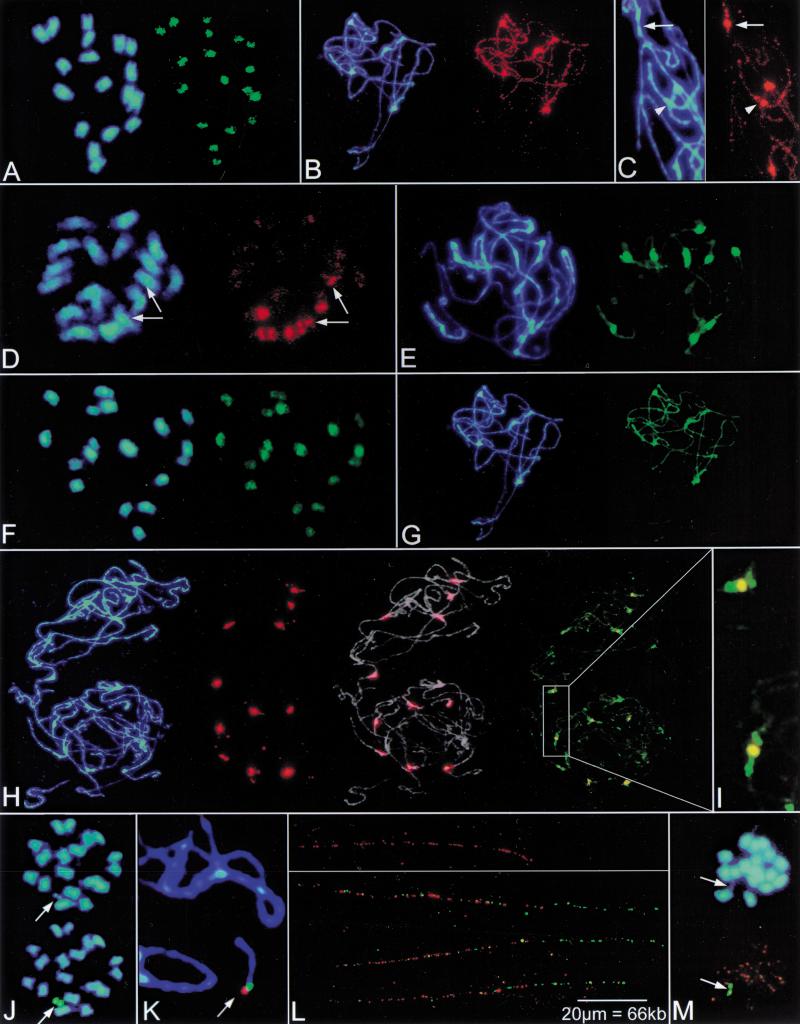

FISH was used to physically map the Ty3-gypsy-like clones pBv26 and pBp10 on mitotic metaphase and meiotic pachytene chromosomes of B. vulgaris and B. procumbens, respectively. Figure 2A shows that pBv26 hybridizes strongly to the centromeric heterochromatin but also extends out to the pericentromeric regions of all nine pairs of B. vulgaris chromosomes.

Figure 2.

Physical mapping of centromere-associated, repetitive sequences on Beta chromosomes by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). Blue fluorescence in panels shows the DNA stained with DAPI. (A) Hybridization of the Ty3-gypsy-like sequence pBv26 to mitotic metaphase chromosomes of B. vulgaris. Signals are largely confined to centromeric regions (green fluorescence). (B) Decondensed, paired chromosomes of B. procumbens at pachytene stage of meiosis. The Ty3-gypsy-like sequence pBp10 strongly hybridizes to the centromeric regions of five chromosome pairs (brightly stained with DAPI) and shows weak dispersion along chromosomes (red fluorescence). (C) Close-up image of the polymorphic pBp10 hybridization (red signal) to pachytene chromosomes of B. procumbens. The Ty3-gypsy-like sequence pBp10 shows confined amplification in the primary constriction (arrow) or clustering in the pericentromeric region with depletion in the constriction (arrowhead). (D) The satellite repeat pHC8 is detectable on three pairs of mitotic metaphase chromosomes of B. lomatogona (red fluorescence). Only one chromosome pair contains pHC8 arrays in the centromeric region (arrows) indicating polymorphisms of the centromeric heterochromatin between chromosomes in Beta species. (E) Pachytene chromosomes of B. vulgaris probed with the satellite family pBV1 (green signals). The satellite forms large arrays within the DAPI-positive heterochromatin of all centromeres. (F) FISH with the oligonucleotide (GATA)4 to a mitotic metaphase plate of B. vulgaris shows that microsatellites are structural components amplified at Beta centromeres. (G) Rehybridization of B. procumbens pachytene chromosomes. After removal of the probe, chromosomes shown in (B) were hybridized with the satellite repeat pTS5 (strong green fluorescence). Note that the pTS5 satellite family colocalizes with DAPI-positive regions which also showed amplification of the Ty3-gypsy-like sequence pBp10. (H) Multicolor FISH of differently labeled satellite repeats to pachytene chromosomes of two cells of a heterozygous B. procumbens plant. The satellite family pTS5 (red signals) is amplified at most centromeres (middle left), the merged image (middle right) shows the morphology of decondensed pachytene chromosomes (gray) to indicate sites of hybridization. Examination with Filter 09 (right) shows that pTS4.1 satellite arrays (green signals) flank the prominent TS5 repeats (yellow). (I) Close examination of (H) showing the physical order of the pTS5 (yellow) and pTS4.1 (green) satellites at B. procumbens centromeres. (J) The chromosomal mutant PRO1 of B. vulgaris contains a B. procumbens chromosome fragment, which resembles a minichromosome. At mitotic metaphase, the PRO1 minichromosome is highly condensed, and both chromatides are visible (arrow). The minichromosome shows strong signals after FISH with the satellite repeat pTS5 (green fluorescence, arrow). (K) Close-up of FISH to pachytene chromosomes of PRO1. The arrow points to the minichromosome. Hybridization with the satellite pTS5 (red signal) and pTS4.1 (green signal) indicates that the centromeric region is close to the physical end of the minichromosome. (L) FISH to extended DNA fibers reveals the order of B. procumbens satellite repeats in the centromeric region of the PRO1 minichromosome. Stretches of red fluorescence indicate arrays of the satellite pTS5 (top panel). Note, that the pTS5 arrays are interrupted, detectable as gaps within the string of fluorescence signals. Double-target hybridization shows that the satellite pTS4.1 (green signals) forms an array adjacent to the longer pTS5 repeat block (red signals). Three examples are shown (lower panel). Yellow fluorescence indicates overlapping signals caused by interspersion of pTS4.1 repeats within gaps of the neighboring pTS5 array. (M) In the chromosomal mutant PAT2, the chromosome fragment from B. patellaris forms a minichromosome that is barely visible after DAPI staining (top, arrow) but is clearly detectable after FISH with the satellite repeat pTS5 (bottom, green fluorescence). Orange signals originate from simultaneous hybridization of the telomeric repeat (TTTAGGG).

A higher mapping resolution of Ty3-gypsy-like sequences was achieved using B. procumbens chromosomes at pachytene of meiosis. At this stage, the chromatin is less condensed (De Jong et al. 1999), and the homologous chromosomes are paired completely, which gives rise to only one-half the number of signals. In B. procumbens, clusters of Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons are detected on five chromosome pairs; the signals clearly correspond to the centromeric heterochromatin visible as bright DAPI-stained regions (Fig. 2B). Weak dispersed hybridization signals along all chromosome arms indicate additional interspersed copies of pBp10 and related Ty3-gypsy-like sequences in the genome of B. procumbens. The signal intensity of pBp10 in B. procumbens appeared to be weaker compared with pBv26 in B. vulgaris, which shows that pBp10 represents a less abundant or diverged subfamily of Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons in the B. procumbens genome. Interestingly, different patterns of centromeric organization of Ty3-gypsy-like sequences were observed using pBp10 as a probe:

confined amplification of the retrotransposons within the central constriction and smaller clusters in the flanking large heterochromatic blocks (Fig. 2C, arrow),

clustering in the pericentromeric heterochromatin with no detectable signal in the central constriction (Fig. 2C, arrowhead),

no detectable amplification of Ty3-gypsy-like sequences.

Another important sequence class that is associated with centromeric heterochromatin is satellite repeats. A novel satellite DNA family, represented by the monomer pHC8 (AJ243337), has been identified in the section Corollinae of the genus Beta. Members of this sequence family are 162-bp long, AT-rich (67%), contain numerous short runs of homo-oligonucleotides and a conserved HaeIII site. FISH analysis of this satellite repeat has been performed on mitotic metaphase chromosomes of the diploid Corollinae species B. lomatogona (2n = 2x = 18). The pHC8 satellite family is located on three chromosome pairs (Fig. 2D). However, only one pair showed signals in the centromeric region (Fig. 2D, arrows), whereas the other two chromosome pairs contain intercalary pHC8 arrays on either one or two chromosome arms. This chromosome-specific centromeric localization might represent an interesting exception, as all other centromeric satellite families among the numerous satellite repeats isolated from the genus Beta (for review, see Kubis et al. 1998) are not restricted to single centromeres as shown by FISH (Fig. 2E,G,H). The satellite repeat pBV1, for example, is exclusively localized in the centromeric heterochromatin of all B. vulgaris chromosomes (Fig. 2E), where it extends over regions of several hundred kilobase pairs as shown by PFGE (Schmidt and Metzlaff 1991). A similar localization is observed using the microsatellite motif CA as a FISH probe (not shown). However, as many members of the pBV1 satellite family contain a variable region of CA dinucleotides, it cannot be excluded that this satellite contributes, at least in part, to the detected FISH signals. Nevertheless, microsatellite arrays are contributing to centromeric heterochromatin of at least eight B. vulgaris chromosomes as shown for the microsatellite motif GATA (Fig. 2F).

Like pBV1 in B. vulgaris, the prominent satellite family pTS5 of the section Procumbentes is also localized at centromeres. Depending on the genotype (homozygous or heterozygous) this satellite repeat exclusively labels the centromeric region of 10–12 of the 18 chromosomes. Another nonhomologous satellite family, pTS4.1, gives strong centromeric hybridization signals on eight of the nine chromosome pairs (Schmidt and Heslop-Harrison 1996).

By multicolor FISH on B. procumbens pachytene chromosomes we determined the organization of these two satellite families at high resolution, showing that pTS4.1 is localized in the pericentromeric regions and flanks large pTS5 repeat blocks (Fig. 2H,I). Interestingly, the satellite pTS5 was found at all centromeric sites, which also showed strong amplification of the Ty3-gypsy-like sequence pBp10. Subsequent hybridization with pTS5 and pBp10 showed that both sequence classes colocalize (Fig. 2B,G).

All identified repetitive sequences associated with Beta centromeres are summarized in Table 1. According to their chromosomal organization they were assigned to three classes reflecting their exclusive presence on all or most centromeres (class I and class II) or on centromeres with additional dispersed distribution (class III).

Table 1.

Repetitive Sequences Associated with Beta Centromeres

| Class | Repeat | Type | Length (bp) | Origin | Distribution within sections of the genus Beta | Chromosomal position | Figure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pBV1 | Satellite DNA | 326–327 | B. vulgaris | Beta (amplified) | all centromeres | 2E | Schmidt and Metzlaff (1991) |

| 2 | pTS5 | Satellite DNA | 158–160 | B. procumbens | Procumbentes (amplified) | most centromeres | 2G,H,J,M,L | Schmidt and Heslop-Harrison (1996) |

| pTS4.1 | Satellite DNA | 312 | B. procumbens | Procumbentes (amplified) | 2H,K,L | |||

| 3 | pBp10 | Ty3-gypsy-like element | 417 | B. procumbens | Beta, Corollinae, Nanae(amplified) Procumbentes (low copy) | centromeres and dispers | 2B,C | this paper |

| pBv26 | Ty3-gypsy-like element | 417 | B. vulgaris | Beta, Corollinae, Nanae(amplified) Procumbentes (low copy) | 2A | this paper | ||

| pHC8 | Satellite DNA | 162 | B. corolliflora | Corollinae (amplified) Beta, Nanae (low copy) | 2D | this paper |

Not listed are the microsatellite motifs CA or GATA (Fig. 2A) which show a class 3 chromosomal distribution.

Evolutionary Aspects of Centromere-Associated Repeated DNA of Beta Genomes

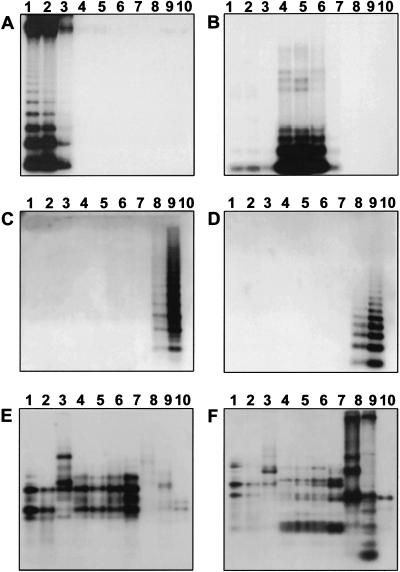

We investigated the genomic organization and conservation of the six centromere-associated repetitive elements listed in Table 1 within all four sections of the genus Beta using genomic Southern blot hybridization. As a related outgroup species Spinacea oleraceawas included, which belongs like Beta to the Chenopodiacae family.

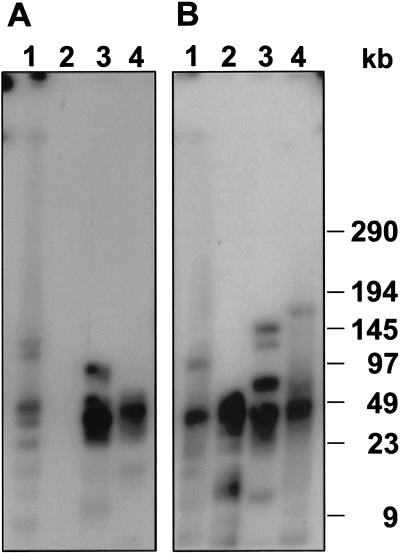

The satellite repeats pBV1, pHC8, pTS4.1, and pTS5 produced a ladder pattern, which is typical for a tandemly repeated organization (Fig. 3A–D3). The satellite families showed exclusive amplification in individual sections only; the high abundance and similar hybridization indicate that these repeat families are conserved. Because pHC8 is also present in low abundance in two additional sections, we concluded that pHC8 is an ancient sequence that was already present in the progenitor of the sections Beta, Corollinae, and Nanae but was reamplified only in the section Corollinae in which speciation is still an ongoing process (L. Frese, pers. comm.).

Figure 3.

Genomic organization and conservation of six centromere-associated repetitive sequences of the genus Beta. Representative species of the sections Beta (1–3), Corollinae (4–6), Nanae (7), and Procumbentes(8–9) were investigated. The following samples were loaded: (1) B. vulgaris (cultivar 'Rosamona'), (2) B. vulgaris cicla, (3) B. patula, (4) B. corolliflora, (5) B. lomatogona, (6) B. macrorhiza, (7) B. nana, (8) B. procumbens, and (9) B. patellaris. Spinacea oleracea(10) was included as an out-group species. Genomic DNA was digested with (A) BamHI, (B) HaeIII, (C,D) Sau3AI, and (E,F) RsaI, size-separated and transferred onto nylon membranes. Filters were hybridized with (A) pBV1, (B) pHC8, (C) pTS4.1, (D) pTS5, (E) pBv26, and (F) pBp10.

Our results indicate that in most cases satellite amplification took place after separation of species or species groups. The pattern of amplification and possible reamplification of centromeric satellites matches the phylogeny of the genus Beta (Kubis et al. 1998).

In contrast to the satellite families the two Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons pBv26 and pBp10 showed complex hybridization patterns that are specific for each element (Fig. 3E,F). The hybridization pattern of pBv26 was similar in most analyzed Beta species, whereas only a subset of the restriction fragments detected by pBp10 appeared to be conserved across the Chenopodiacae.

Alignment of the predicted protein sequences of pBv26 and pBp10 with the corresponding domains of other Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons revealed a remarkable degree of conservation between these elements, especially at the N-terminal portion of the shown domains (Fig. 1). Although pBp10 is more closely related to the listed Ty3-gypsy-like sequences in rice, sorghum, and A. thaliana than it is to pBv26 from sugar beet, analysis of >20 Ty3-gypsy-like sequences of all Beta sections revealed considerable conservation of these sequences within the genus (Galasso, in prep.). Compared with other retrotransposons such as Ty1-copia-like retroelements (Flavell et al. 1992), the analyzed Ty3-gypsy-like sequences showed a notably lower divergence.

Minichromosome Mutants: An Experimental System Toward the Characterization of Beta Centromeres

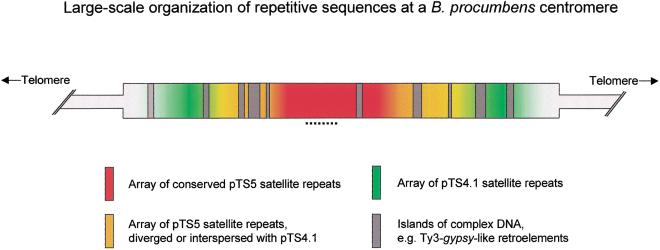

Based on the data shown above we developed a model of the large-scale organization of the heterochromatin at a B. procumbens centromere (Fig. 4). According to our model, the centromeric region consists of at least three different major DNA sequences: Two nonhomologous satellite DNAs and Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons and possibly microsatellites as shown in B. vulgaris, which lead to a hierarchical tripartite structure.

Figure 4.

A model of the organization of repetitive DNA sequences at a Beta procumbens centromere. Major satellite families are represented by different colors. The region containing the presumable chromosomal breakpoint that results in the PRO1 minichromosome is indicated by a dotted line. Not included are microsatellite sequences, such as GATA.

The central region is predominantly composed of the satellite repeat pTS5 with a monomer length of 158–160 bp (Fig. 2H,I). Under stringent hybridization conditions (79%) it has been shown that this array is made up of diverged subfamilies with 70%–75% homology to each other and that more diverged copies flank a central repeat block of conserved pTS5 monomers (Schmidt and Heslop-Harrison 1996). Arrays of the nonhomologous satellite repeat pTS4.1, which has a monomer length of 312 bp, flank this central pTS5 region. It is likely that some interspersion of the satellite repeats pTS5 and pTS4.1 occurs and that the arrays are not completely spatially separated (Fig. 2L). In addition, Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons (pBp10) were colocalized within the centromeric region, and we assume that they form islands of higher sequence complexity (Fig. 2B). Superimposed on the model of the organization of repetitive sequences around the centromere (Fig. 4), our data indicate that there are interchromosomal polymorphisms in the primary sequence, abundance of each class, and organization among individual centromere regions (Fig. 2B,C,G,H). Such variation is likely to be of key importance in differentiating chromosomes during meiotic pairing and segregation.

To verify this structural model, a Beta centromere has to be analyzed on the molecular level. Suitable experimental systems are monosomic addition lines selected from interspecific Beta hybrids. Here, an alien chromosome is detectable with genome-specific DNA probes that are maintained in a heterologous genetic background, which prevents possible ambiguities in physical mapping caused by allelic variations as the centromere of a single chromosome can be analyzed.

There are a number of chromosomal mutants in B. vulgaris; of particular interest are the lines PRO1 and PAT2, which contain a chromosome fragment of B. procumbens or B. patellaris, respectively. These chromosome fragments resemble single functional minichromosomes added to the full B. vulgaris complement. Based on a haploid genome size, a B. vulgaris chromosome contains, on average, 80–85 Mbp DNA. From measurements of several DAPI-stained cells at pachytene, we calculated that the minichromosome in PRO1 has a size of 6–9 Mbp, whereas the B. patellaris-derived fragment in PAT2 is even smaller.

The two satellite families, pTS4.1 and pTS5, are highly specific for the section Procumbentes (Fig. 3C,D). At mitotic metaphases pTS5 was exclusively detected on the wild-beet-derived chromosome fragments (Fig. 2J,M). FISH on PRO1 meiotic pachytene chromosomes using pTS5 and pTS4.1 as probes showed that the arrays of these centromere-associated satellite families reside close to one end of the minichromosome (Fig. 2K). Therefore, it can be concluded that the minichromosome in PRO1 is acrocentric.

We also performed FISH to DNA fibers released from lysed PRO1 nuclei to estimate the array size, interspersion pattern, and higher order organization of the two satellite families on the PRO1 minichromosome.

Based on a stretching degree of 3.3 kb/μm, a molecular resolution can be achieved by FISH to extended DNA fibers (Fransz et al. 1996). Measurement of 15 PRO1 nuclei revealed an array size of ∼65 μm for the pTS5 satellite family (Fig. 2L, top panel). Gaps within the fluorescent tracks indicatedthat this array is not homogenous but is interrupted by unrelated sequences. For the pTS4.1 array, we determined a size of 35.5–37.3 μm (Fig. 2L, green signals in lower panel). In addition, FISH to DNA fibers showed that there is no gap between the two satellite regions. The relative orientation of the satellite blocks can be concluded from the hybridization of these satellites to PRO1 pachytene chromosomes (Fig. 2K), showing a distal localization of pTS5. Because of the detection of a single pTS4.1 signal adjacent to the pTS5 array (Fig. 2K,L), we assume that chromosome breakage occurred in the pTS5 satellite block that occupies the physical end of the PRO1 minichromosome.

The hybridization pattern of large restriction fragments that contain centromere-associated satellites is consistent with the relatively small array sizes detected by FISH on extended DNA fibers (Fig. 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Southern hybridization of high-molecular-weight DNA fragments of the minichromosome containing Beta vulgaris line PRO1. DNA was digested with HindIII (1), HaeIII (2), HpaII (3), XbaI (4), and restriction fragments were separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. After transfer onto nylon membranes, filters were hybridized with radioactively labeled pTS4.1 (A) and pTS5 (B).

Fragments that harbor the majority of pTS5 and pTS4.1 repeats, which are indicated by strong hybridization signals, are <50 kb. Weaker bands correspond to fragments with fewer repeats, or they originate from flanking regions. The monomer of pTS4.1 has three internal HaeIII recognition sites and this restriction enzyme digests the satellite array to completion as no restriction fragments were detected (Fig. 5A, lane 2). Therefore, we assume that monomers of this satellite family are relatively homogenous in PRO1 and that the intensity of hybridization signals correspond to copy number and not to sequence divergence of the satellite repeats.

In the B. vulgaris chromosome mutant line PAT2, the wild beet minichromosome is considerably smaller. In DAPI-stained metaphases, the minichromosome is hardly visible (Fig. 2M, arrow), and a weaker signal of the pTS5 array is observed, which shows that fewer copies of this satellite repeat are present. Although both minichromosomes are faithfully inherited in mitosis, the meiotic stability of the PAT2 chromosome fragment is drastically reduced compared with PRO1 (18.3% vs. 34.8%; Brandes et al. 1987,1992). As it cannot be excluded that regions necessary for full centromeric activity are at least partially deleted in the PAT2 minichromosome, PRO1 represents the more suitable experimental system in which to study Beta centromeres.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe the molecular structure and organization of various repetitive DNA sequences that are associated with the centromeres of Beta chromosomes and developed a structural model of the centromeric region of a wild beet. Furthermore, we present an experimental system that provides access to the molecular analysis of centromeric DNA using chromosomal mutants that contain a single acrocentric minichromosome.

Centromeres are essential DNA domains that are necessary for the faithful segregation of chromosomes at mitosis and meiosis in eukaryotes, except for organisms with holocentric chromosomes like Caenorhabditis elegans (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998). In contrast to telomeres, which are very conserved in plants and even among higher eukaryotes, centromeres appear much more variable. While the telomeric DNA consists of simple repeats enzymatically added to the physical ends of the chromosomes by telomerases, the DNA at centromeres is an integral component of the chromosomes and is subject to evolution and has a far more complex structure and organization, even within a single species.

Evidence comes from molecular analyses of the centromeric heterochromatin of A. thaliana chromosomes 2 and 4, which reveals only a limited degree of similarity in these chromosomal regions (Arabidopsis Genome Sequencing Consortium 1999; Copenhaver et al. 1999; Lin et al. 1999).

Similar to other eukaryotes, plant centromeric regions consist of repetitive DNA, and many satellite families and retroelements have been isolated and localized there by in situ hybridization (Kamm et al. 1994; Harrison and Heslop-Harrison 1995; Aragon-Alcaide et al. 1996; Brandes et al. 1997). However, only a small number of centromeric repeat families have been studied in more detail (Jiang et al. 1996b; Round et al. 1997; Dong et al. 1998; Heslop-Harrison et al. 1999), and information about their organization is limited. Knowledge of the spatial arrangement of major satellite arrays is critical for understanding the long-range organization of the DNA at centromeres. FISH to mitotic metaphase chromosomes has only a resolution of ∼2–5 Mbp (Trask 1991; Jiang et al. 1996a). Higher resolution is achieved when extended chromosomal targets, such as DNA fibers or meiotic chromosomes, are used for FISH studies (De Jong et al. 1999; Fransz et al. 2000).

We performed FISH to pachytene chromosomes and DNA fibers (Fig. 2B,G,H,I) to develop a structural model of the large-scale organization of repetitive sequences at a B. procumbens centromere (Fig. 4).

According to our model, this chromosomal region has a hierarchical tripartite structure and consists of different repetitive sequence elements including Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons. The central array is mainly composed of conserved monomers of the satellite pTS5 bordered by diverged subfamilies (Schmidt and Heslop-Harrison 1996). Arrays of the nonhomologous satellite repeat pTS4.1 flank this central region.

Misdivision analyses of B-chromosome derivatives in maize have shown that 370 kb of centromeric DNA is the minimum size required for stable meiotic transmission (Kászas and Birchler 1998). Based on several in situ hybridizations to DNA fibers, we calculated that the pTS5 array in PRO1 is ∼215 kb in size, whereas the array of the pTS4.1 satellite repeats extends over 117–123 kb. This would correspond to <1300–1400 pTS5 repeats and 300–400 pTS4.1 repeats, which is probably an overestimation because of the gaps detected in the fluorescent tracks (Fig. 2L). Simultaneous hybridization with pTS5 and pTS4.1 also gave insight into the nature of the gaps in the pTS5 arrays: Some of them consist of pTS4.1 sequences as indicated by green and yellow fluorescence. As the PRO1 minichromosome is acrocentric and only a single pTS4.1 array was observed on extended DNA fibers and meiotic chromosomes (Fig. 2L,K), we conclude that one breakpoint of the minichromosome is located within the centromeric pTS5 array of the B. procumbens wild-type chromosome. This is consistent with FISH to DNA fibers of monosomic addition lines of B. procumbens in B. vulgaris, which has shown that members of the pTS5 satellite family form arrays that span alone <755 kb (Mesbah et al. 2000). The centromeric location of the breakpoint would also explain the reduced meiotic stability of the PRO1 minichromosome, and it is tempting to speculate about the location of the breakpoint in the PAT2 minichromosome, which has an even lower transmission rate.

An ordered arrangement of satellite DNA has also been found at human centromeres. Here, the central α-satellite is surrounded by the nonhomologous satellites 1–3 or β-satellite residing in the pericentromeric regions of many chromosomes (for review, see Choo 1997). A hallmark of the human α-satellite is the largely chromosome-specific organization in distinct subfamilies. Similarly, the pTS5 satellite is a repetitive sequence family of the B. procumbens genome, and the monomers analyzed so far revealed a considerable degree of sequence divergence. The pTS5 arrays are not detectable on all B. procumbens centromeres under standard hybridization conditions, and an explanation for this finding might be repeat divergence or variation in abundance between different chromosomes.

Chromosome-specific variants of satellites have also been observed in other plants such as Brassica, Zea mays, and A. suecica (Harrison and Heslop-Harrison 1995; Kamm et al. 1995; Ananiev et al. 1998). In the model species A. thaliana, the 180-bp satellite repeat pAL1 contributes to most of the centromeric heterochromatin as examined by FISH (Maluszynska and Heslop-Harrison 1991). The existence of chromosome-specific pAL1 arrays in A. thaliana has been shown recently by primed in situ hybridization using conserved regions of the satellite monomer. In addition, two boxes with notable similarity to the binding motif of the centromeric protein B (CENP-B) were found in pAL1 (Heslop-Harrison et al. 1999). This 17-bp motif has also been found in many α-satellite repeats (for review, see Choo 1997). There are convincing studies showing that the human α-satellite DNA is involved in centromere formation and nucleation of the kinetochore (Haaf et al. 1992). Synthetic arrays of α-satellite repeats in human artificial chromosomes provided experimental evidence that an array of binding sites of CENP-B is sufficient for kinetochore assembly (Harrington et al. 1997; Ikeno et al. 1998; Henning et al. 1999). However, even if CENP-B is not essential for proper chromosome segregation (Hudson et al. 1998; Perez-Castro et al. 1998), it might be important for the organization and arrangement of centromeric DNA (Kipling and Warburton 1997).

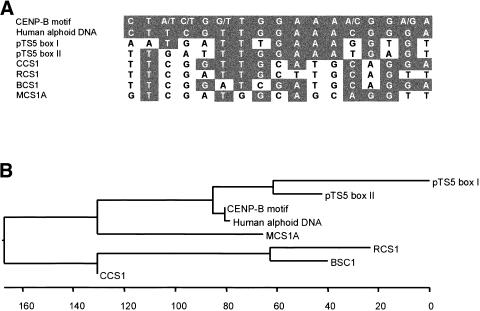

Interestingly, the consensus sequence derived from >20 B. procumbens and B. patellaris monomers that belong to the pTS5 satellite family revealed two regions, designated box I and box II, which show similarity to the CENP-B-binding motif (Fig. 6). CENP-B box-like motifs have also been found in other plant centromeric repeats; however, many of them are not satellites but derivates of Ty3-gypsy-like retrotransposons (Aragon-Alcaide et al. 1996; Kipling and Warburton 1997; Presting et al. 1998; Nonomura and Kurata 1999).

Figure 6.

Alignment of sequences showing homology with the CENP-B motif. The following plant centromeric sequences were included: pTS5 fromBeta procumbens (this paper), CCS1 from Brachypodium sylvaticum, RCS1 from Oryza sativa, BCS1 from Hordeum vulgare, and MCS1A from Zea mays (all taken from Aragon-Aclaide et al. 1996). (A) Nucleotides matching the CENP-B motif are shaded. (B) Cladogram representing the homology of plant centromeric sequences containing a region with similarity to the CENP-B consensus motif and the CENP-B sequence of the human alphoid DNA (Choo 1997).

The repetitive DNA at plant centromeres extends over large regions that are easily detectable by DAPI as C-bands at microscopic level in Beta species (e.g., Fig. 2B,E, H). The physical mapping of the A. thaliana genome and sequencing of chromosomes 2 and 4 have shown that it is difficult to assemble contigs spanning centromeric regions of intact chromosomes with clones from large-insert libraries (Arabidopsis Genome Sequencing Consortium 1999; Copenhaver et al. 1999; Lin et al. 1999; Mozo et al. 1999).

It may be more favorable to use subchromosomal derivates, such as minichromosomes or supernumerary B chromosomes (Alfenito and Birchler 1993; Kászas and Birchler 1996; Sun et al. 1997; Kászas and Birchler 1998). The molecular dissection of a D. melanogaster minichromosome showed that a functional centromere is located within a 420-kb region that consists of a 220-kb island predominantly composed of tandemly repeated DNA interspersed with few transposable elements. This core region is flanked by a 200-kb region of another nonhomologous family of tandemly repeated DNA (Sun et al. 1997). Therefore, the chromosomal mutants PRO1 or PAT2 of B. vulgaris are a suitable experimental system for the analysis of plant centromeres. Although both minichromosomes are mitotically stable, they differ in transmission rates during meiosis (Brandes et al. 1987,1992). Comparative mapping of centromeric regions might reveal DNA sequences necessary for full centromere function in meiosis. For PRO1 the physical mapping by PFGE and FISH to extended DNA fibers indicated that the satellite DNA associated with B. procumbens centromeres contained in restriction fragments that should be clonable in artificial chromosome vectors. Multicolor high-resolution FISH on pachytene chromosomes with selected large-insert clones can support contig establishment and might enable assignment of physical maps to specific regions of the minichromosome.

Although the molecular composition of eukaryotic centromeres appears to be variable even between chromosomes of a single species, it follows similar structural rules. Our model of a wild beet centromere is, with respect to the overall structure, consistent with centromeres from human, D. melanogaster, and A. thaliana. Our data indicate that centromeres of Beta have a complex anatomy caused by both chromosome-specific and ubiquitous sets of repeated DNA elements. We could identify elements that are specific for Betacentromeres, whereas others are accumulated there but show also additional distribution in other chromosomal regions. Based on their chromosomal distribution, we grouped the DNA sequences into three different classes that reflect different centromere specificity (Table 1). It remains to be determined whether these elements indeed provide centromere activity and serve as sites of spindle attachment or if they are subject to epigenetic modulations such as DNA methylation, histone modification, or formation of higher-order structures as suggested (Sun et al. 1997; Copenhaver and Preuss 1999).

METHODS

Plant Material and DNA Preparation

Plants were grown under greenhouse conditions. The following species were included in this study: B. vulgaris (cultivar 'Rosamona'), B. vulgaris cicla (accession no. 56736), B. patula (accession no. 56782), B. corolliflora(accession no. PI 264352), B. lomatogona (accession 17830), B. macrorhiza (accession no. 18259), B. nana(accession no. 81FD6), B. procumbens (accession no. 35336), and B. patellaris (accession 57667). Wild beet seeds were obtained from Dr. L. Frese ) and Dr. B. Ford-Lloyd. The chromosomal B. vulgaris mutants PRO1 and PAT2 were selected for the presence of the minichromosome from B. procumbens and B. patellaris, respectively, by dot blot hybridization using radioactively labeled wild beet DNA (Schmidt et al. 1990).

Genomic DNA was isolated from young leaves using a CTAB (cetyltrimethyl/ammonium bromide) standard protocol (Saghai-Maroof et al. 1984). High-molecular-weight DNA for PFGE was isolated according to Zhang et al. (1995).

Restriction Analysis and Southern Hybridization

For conventional gel electrophoresis, genomic DNA (7 μg) was digested to completion with BamHI, HaeIII, or RsaI and separated in 1.2% agarose gels in 1 × TAE (40 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.114% acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA). High-molecular-weight DNA embedded in agarose plugs was incubated overnight with 100 units restriction enzyme (HindIII, HaeIII, HpaII, or XbaI) and the appropriate buffer in a total volume of 200 μL. After digestion, the DNA was separated in a CHEF-DRIII system (Biorad) in 1% agarose gels (Seakem LE) in 1 × TAE using the following conditions: Linear ramping with switch times 1–40 sec, 6 V/cm voltage, 16-h running time, 14°C buffer temperature, 120° included angle.

For Southern hybridization, agarose gels were transferred onto positively charged nylon membranes (Pharmacia Amersham). Gels containing high-molecular-weight DNA fragments separated by PFGE were exposed to UV light for 3 min before transfer. Filters were hybridized at 60°C overnight and washed twice at 60°C in 1×SSC/0.1% SDS for 30 min.

DNA Probes and Labeling

Repetitive DNA sequences of Beta centromeres used as probes are listed in Table 1.

Sequences pBv26 and pBp10 are derived from Ty3-gypsy retrotransposons and were amplified from genomic beet DNA with the degenerated primers GYR1 (MRNATGTGYGTNGAY TAYMG) and GYR4 (RCAYTTNSWNARYTTNGCR) described by Friesen et al. (2001). After initial denaturation at 94°C, PCR was performed in an MJ Research thermocycler PCT200 for 35 cycles using the following program: 50 sec annealing at 39°C, 40 sec elongation at 72°C, and 90 sec denaturation at 94°C.

The centromeric satellite DNA repeats pTS5, pTS4.1, and pBV1 isolated from B. procumbens and B. vulgaris, respectively, were used in this study and have been previously described (Schmidt and Metzlaff 1991; Schmidt and Heslop-Harrison 1996). The novel satellite repeat pHC8 was identified as a highly repetitive DNA fragment in size-fractionated, HaeIII digested B. corollifloraDNA. Restriction satellites and PCR products were cloned and sequenced according to standard protocols (Sambrook et al. 1989). For Southern hybridization, probes were labeled with 32P-dCTP and 32P-dATP by random priming. For FISH, DNA probes cloned in plasmid vectors were labeled by insert PCR with M13 universal primers in the presence of biotin-11-dUTP or digoxigenin-11-dUTP. The oligonucleotide (GATA)4 was 3′-endlabeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP by terminal transferase, according to the instruction of the manufacturer (Roche).

Preparation of Chromosomes and Extended Chromatin Fibers

The meristem of young leaves and flower buds were used for the preparation of mitotic and meiotic chromosomes, respectively. Before fixation in methanol:acetic acid (3:1), leaves were incubated for 3–5 h in 2 mM 8-hydroxyquinoline. Fixed plant material was macerated in an enzyme mixture consisting of 0.3% (w/v) cytohelicase (Sigma), 1.8% (w/v) cellulase from Aspergillus niger (Sigma), 0.2% (w/v) cellulase Onozuka-R10 (Serva), and 20% (v/v) pectinase from A. niger and squashed onto slides as described (Desel et al. 2001). Extended DNA fibers were prepared according to Fransz et al. (1996) with some modifications. After spotting onto microscope slides and air drying, nuclei were disrupted in 10 μL STE (0.5% SDS, 50mM EDTA, 100mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0). Following a 5-min incubation at room temperature, the released chromatin was stretched by tilting the slide. DNA fibers were rinsed in methanol:acetic acid (3:1) and fixed on the glass surface by incubation at 60°C for 3 h.

Fluorescent in situ Hybridization

FISH to Beta chromosomes was performed as described by Schmidt et al. (1994) with some modifications. After denaturation of chromosomes at 70°C for 8 min, temperature was decreased stepwise, and hybridization was performed in 50% formamide/2 × SSC in a moist chamber at 37°C. DNA fibers were denatured in 70% formamide in 2 × SSC at 70°C for 2 min, dehydrated in a cold ethanol series and air dried before application of the heat-denatured hybridization mixture. After hybridization slides were washed in 20% formamide/0.2 × SSC at 42°C followed by several washes in 2 × SSC at 42°C. Slides were equilibrated in detection buffer consisting of 4 × SSC/0.2% (v/v) Tween 20 and blocked in 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in detection buffer. For immunochemical detection of hybridization sites, slides were incubated with 2.6 μg/mL sheep anti-digoxigenin-FITC (Roche) or 5.6 μg/mL streptavidin conjugated to Cy3 (Roche) in 3% BSA/4×SSC/0.2% Tween 20. Chromosome preparations were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and mounted in antifade solution (Vectashield H-1000).

For reprobing, slides were washed in 2 × SSC for an extended period of time, dehydrated in an ethanol series, and rehybridized. Examination of slides was performed with a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan 2 imaging) equipped with Filter 09 (FITC), Filter 15 (Cy3), and Filter 01 (DAPI).

Photographs were taken on Fujicolor SUPERIA 400 print film. Negative films were digitized on a Nikon LS-1000 scanner, contrast optimized using only functions affecting the whole image equally, and printed using Adobe Photoshop software.

Sequencing and Computer Analysis

Clones representing novel centromeric repeats were sequenced on LI-COR automated sequencers using a cycle-sequencing kit (Biozyme). The software DNAStar was used for the analysis of sequence data. For the calculation of the CENP-B motif similarities, the default parameters were used.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pat Heslop-Harrison for critical reading of the manuscript and Nicole Pinnow for technical assistance. This work is funded by grants from the BMBF (BioFuture grant 0311860), DFG (Schm1048/2–3), and DAAD projects ARC 9704415 and 418 ITA 112/11/99.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL tschmidt@plantbreeding.uni-kiel.de; FAX 49-431-880-2566.

Article and publication are at www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.162301 .

REFERENCES

- Alfenito MR, Birchler JA. Molecular characterization of a maize B chromosome centric sequence. Genetics. 1993;135:589–597. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananiev EV, Phillips RL, Rines HW. Chromosome-specific molecular organization of maize (Zea maysL.) centromeric regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:13078–13078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragon-Alcaide L, Miller T, Schwarzacher T, Reader S, Moore G. A cereal centromere sequence. Chromosoma. 1996;105:261–268. doi: 10.1007/BF02524643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumuganathan K, Earle ED. Nuclear DNA content of some important plant species. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1991;9:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes A. “Erstellung und Charakterisierung von nematodenresistenten Additions- und Translokationslinien bei B. vulgaris L.” Ph.D. thesis. Germany: University of Hannover; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes A, Jung C, Wricke G. Nematode resistance derived from wild beet and its meiotic stability in sugar beet. Plant Breed. 1987;99:56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes A, Thompson H, Dean C, Heslop-Harrison JS. Multiple repetitive sequences in the paracentromeric regions of Arabidopsis thalianaL. Chromosome Res. 1997;5:238–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1018415502795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo KHA. The centromere. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L. Centromeres of budding and fission yeast. Trends Genet. 1990;6:150–154. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(90)90149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L, Carbon J. Isolation of a yeast centromere and construction of functional small circular chromosomes. Nature. 1980;287:504–509. doi: 10.1038/287504a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver GP, Preuss D. Centromeres in the genomic era: unraveling paradoxes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:104–108. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver GP, Nickel K, Kuromori T, Benito M-I, Kaul S, Lin X, Bevan M, Murphy G, Harris B, Parnell LD, et al. Genetic definition and sequence analysis of Arabidopsis centromeres. Science. 1999;286:2468–2474. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong JH, Fransz P, Zabel P. High resolution FISH in plants – techniques and applications. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:258–263. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desel, C., Jung, C., Cai, D., Kleine, M., and Schmidt, T. 2001. High resolution mapping of YACs and single-copy gene Hs1pro-1on Beta vulgaris chromosomes by multi-colour fluorescence in situ hybridization. Plant Mol. Biol. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dong F, Miller JT, Jackson SA, Wang G-L, Ronald PC, Jiang J. Rice (Oryza sativa) centromeric regions consist of complex DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:8135–8140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell AJ, Smith DB, Kumar A. Extreme heterogeneity of Ty1-copiagroup retrotransposons in plants. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;231:233–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00279796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransz PF, Alonso-Blanco C, Liharska TB, Peeters AJM, Zabel P, de Jong JH. High resolution physical mapping in Arabidopsis thaliana and tomato by fluorescence in situhybridization to extended DNA fibresers. Plant J. 1996;9:421–430. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.09030421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransz PF, Armstrong S, de Jong JH, Parnell LD, van Drunen C, Dean C, Zabel P, Bisseling T, Jones GH. Integrated cytogenetic map of chromosome arm 4S of A. thaliana: Structural organization of heterochromatic knob and centromere region. Cell. 2000;100:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, N., Brandes, A., and Heslop-Harrison, J.S. 2001.Diversity, origin and distribution of retrotransposons (gypsy and copia) in Conifers. Mol. Biol. Evol. (in press.). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Haaf T, Warburton PE, Willard HF. Integration of human α-satellite DNA into simian chromosomes: centromere protein binding and disruption of normal chromosome segregation. Cell. 1992;70:681–696. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90436-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington JJ, Bokkelen GV, Mays RW, Gustashaw K, Willard HF. Formation of de novocentromeres and construction of first-generation human artificial chromosomes. Nature Genet. 1997;15:345–355. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison GE, Heslop-Harrison JS. Centromeric repetitive DNA sequences in the genus Brassica. Theor Appl Genet. 1995;90:157–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00222197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning KA, Novotny EA, Compton ST, Guan XY, Liu PP, Ashlock MA. Human artificial chromosomes generated by modification of a yeast artificial chromosome containing both human alpha satellite and single-copy DNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:592–597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison JS, Murata M, Ogura Y, Schwarzacher T, Motoyoshi F. Polymorphisms and genomic organization of repetitive DNA from centromeric regions of Arabidopsischromosomes. Plant Cell. 1999;11:31–42. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson DF, Fowler KJ, Earle E, Saffery R, Kalitsis P, Trowell H, Hill J, Wreford NG, de Kretser DM, Cancilla MR, et al. Centromere protein B null mice are mitotically and meiotically normal but have lower body and testis weights. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:309–319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeno M, Grimes B, Okazaki T, Nakano M, Saitoh K, Hoshino H, McGill NI, Cooke H, Masumoto H. Construction of YAC-based mammalian artificial chromosomes. Nature Biotech. 1998;16:431–439. doi: 10.1038/nbt0598-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Hulbert SH, Gill BS, Ward DC. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization mapping: A physical mapping strategy for plant species with large complex genomes. Mol Gen Genet. 1996a;252:497–502. doi: 10.1007/BF02172395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Nasuda S, Dong F, Scherrer CW, Woo S-S, Wing RA, Gill BS, Ward DC. A conserved repetitive DNA element located in the centromeres of cereal chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996b;93:14210–14213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm A, Schmidt T, Heslop-Harrison JS. Molecular and physical organization of highly repetitive, undermethylated DNA from Pennisetum glaucum. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:420–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00286694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm A, Galasso I, Schmidt T, Heslop-Harrison JS. Analysis of a repetitive DNA family from Arabidopsis arenosa and relationships between Arabidopsisspecies. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:853–862. doi: 10.1007/BF00037014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpen GH, Allshire RC. The case for epigenetic effects on centromere identity and function. Trends Genet. 1997;13:489–496. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaszás É, Birchler JA. Misdivision analysis of centromere structure in maize. EMBO J. 1996;15:4246–5255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Meiotic transmission rates correlate with physical features of rearranged centromeres in maize. Genetics. 1998;150:1683–1692. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.4.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipling D, Warburton PE. Centromeres, CENP-B and Tiggertoo. Trends Genet. 1997;13:141–145. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubis S, Schmidt T, Heslop-Harrison JS. Repetitive DNA as a major component of plant genomes. Annals of Botany (Suppl.) 1998;82:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Kaul S, Rounsley S, Shea TP, Benito MI, Town CD, Fujii CY, Mason T, Bowman CL, Barnstead M, et al. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 2 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 1999;402:761–768. doi: 10.1038/45471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maluszynska J, Heslop-Harrison JS. Localization of tandemly repeated DNA sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1991;1:159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Zapater JM, Estelle MA, Somerville CR. A highly repeated DNA sequence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;204:417–423. [Google Scholar]

- Mesbah M, Wennekes-Van Eden J, de Jong JH, De Bock TSM, Lange W. FISH to mitotic chromosomes and extended DNA fibers of Beta procumbens in a series of monosomic additions to beet (B. vulgaris) Chromosome Res. 2000;8:285–293. doi: 10.1023/a:1009271109828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozo T, Dewar K, Dunn P, Ecker JR, Fischer S, Kloska S, Lehrach H, Marra M, Martienssen R, Meier-Ewert S, et al. A complete BAC-based physical map of the Arabidopis thalianagenome. Nature Genet. 1999;22:271–275. doi: 10.1038/10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TA, Karpen GH. Localization of centromere function in a Drosophilaminichromosome. Cell. 1995;82:599–609. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura KI, Kurata N. Organization of the 1.9-kb repeat unit RCE1 in the centromeric region of rice chromosomes. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;261:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s004380050935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Castro AV, Shamanski FL, Meneses JJ, Lovato TL, Vogel KG, Moyzis RK, Pedersen R. Centromeric protein B null mice are viable with no apparent abnormalities. Dev Biol. 1998;201:135–143. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presting GG, Malysheva L, Fuchs J, Schubert I. A Ty3/gypsyretrotransposon-like sequence localizes to the centromeric regions of cereal chromosomes. Plant J. 1998;16:721–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards EJ, Dawe RK. Plant centromeres: structure and control. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(98)80014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round EK, Flowers SK, Richards EJ. Arabidopsis thalianacentromere regions: Genetic map positions and repetitive DNA structure. Genome Res. 1997;7:1045–1053. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.11.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghai-Maroof MA, Soliman KM, Jorgensen RA, Allard RW. Ribosomal DNA spacer-length polymorphisms: mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location and population dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1984;81:8014–8018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.24.8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Heslop-Harrison JS. High resolution mapping of repetitive DNA by in situ hybridization: Molecular and chromosomal features of prominent dispersed and discretely localized DNA families from the wild beet species Beta procumbens. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;30:1099–1119. doi: 10.1007/BF00019545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Genomes, genes and junk: The large-scale organization of plant chromosomes. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Metzlaff M. Cloning and characterization of a Beta vulgarissatellite DNA family. Gene. 1991;101:247–250. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90418-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Junghans H, Metzlaff M. Construction of Beta procumbens-specific DNA probes and their application for the screening of B.vulgaris x B. procumbens(2n = 19) addition lines. Theor Appl Genet. 1990;79:177–181. doi: 10.1007/BF00225948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Schwarzacher T, Heslop-Harrison JS. Physical mapping of rRNA genes by fluorescent in situ hybridization and structural analysis of 5S rRNA genes and intergenic spacer sequences in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) Theor Appl Genet. 1994;88:629–636. doi: 10.1007/BF01253964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoens CR, Gielen J, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. Characterization of highly repetitive sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6753–6766. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.14.6753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Wahlstrom J, Karpen G. Molecular structure of a functional Drosophilacentromere. Cell. 1997;91:1007–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80491-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigation biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The European Union Arabidopsis Genome Sequencing Consortium; The Cold Spring Harbor, Washington University in St. Louis and PE Biosystems Arabidopsis Sequencing Consortium. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 4 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 1999;402:769–777. doi: 10.1038/47134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask BJ. Fluorescence in situ hybridization: Applications in cytogenetics and gene mapping. Trends Genet. 1991;7:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard HF, Waye JS. Hierarchical order in chromosome-specific human α-satellite DNA. Trends Genet. 1987;3:192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HB, Zhao XP, Ding XD, Paterson AH, Wing RA. Preparation of megabase-size DNA from plant nuclei. Plant J. 1995;7:175–184. [Google Scholar]