Abstract

Background

Injection drug use is associated with poor HIV outcomes even among persons receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), but there are limited data on the relationship between non-injection drug use and HIV disease progression.

Methods

We conducted an observational study of HIV-infected persons entering care between January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2004, with follow-up through December 31, 2005.

Results

There were 1,712 persons in the study cohort: 262 with a history of injection drug use (IDU), 785 with a history of non-injection drug use, and 665 with no history of drug use; 56% were white, and 24% were females. Median follow-up was 2.1 years, 33% had HAART prior to first visit, 40% initiated first HAART during the study period, and 306 (17.9%) had an AIDS-defining event or died. Adjusting for sex, age, race, prior antiretroviral use, CD4 cell count, and HIV-1 RNA, patients with a history of injection drug use were more likely to advance to AIDS or death than non-users (adjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 1.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43-2.70, P<0.01). There was no statistically significant difference of disease progression between non-injection drug users and non-users (HR=1.19, 95% CI 0.92-1.56, P=0.19). An analysis among the subgroup who initiated their first HAART during the study period (n=687) showed a similar pattern (IDUs: 1.83, 1.09-3.06, P=0.02; non-IDUs: 1.21, 0.81-1.80, P=0.35). Seventy-four patients had active IDU during the study period, 768 active non-IDU, and 870 no substance use. Analyses based on active drug use during the study period did not substantially differ from those based on history of drug use.

Conclusions

This study shows no relationship between non-injection drug use and HIV disease progression. This study is limited by using history drug use and lumping together different types of drugs. Further studies ascertaining specific type and extent of non-injection drug use in a prospective way, and with longer follow-up, are needed.

Keywords: Injection drug use, non-injection drug use, CD4 cell count, HIV viral load, HIV disease progression, antiretroviral therapy

Introduction

Highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) decreases HIV-related morbidity and mortality, but HIV-infected drug users may not fully benefit from these treatment advances [1]. HIV-infected individuals with a history of drug use have delayed access to, or reduced uptake of, HAART [2-3], lower rates of adherence to HAART compared with other HIV-infected subgroups [4-6], and demonstrate inferior virologic control and clinical outcomes [7-13]. Many studies have focused on injection drug users (IDUs), and most of these studies suggest an association between history of injection drug use and HIV disease progression outcomes such as AIDS and death [2-3, 11-12]. There are limited data on the relationship between non-injection drug use and HIV disease progression. The few studies examining only non-IDUs have mixed findings [8-9, 14-15]. The Women's Interagency HIV Study showed that pattern and type of non-injection drug use were associated with HIV progression to AIDS and all-cause mortality [14], and use of crack cocaine independently predicted AIDS-related mortality, immunologic and virologic markers of HIV-1 disease progression (e.g., CD4 cell count, or plasma HIV-1 RNA level), and development of AIDS-defining illnesses among women [8]. Another study also suggested that crack-cocaine use facilitates HIV disease progression by reducing adherence in those on HAART and by accelerating disease progression independently of HAART [15]. An early study among men who have sex with men found that there was no association between marijuana and other recreational drugs with progression to AIDS after adjusting for zidovudine use [9]. However, we are unaware of any studies investigating the association between history of injection drug use and non-injection drug use and HIV disease progression in the same cohort. This study compares HIV disease progression in IDUs, non-IDUs and non-users from the time of entry into clinical care and time of HAART initiation.

Methods

Clinical setting and data collection

This study used data from patients receiving care at the Comprehensive Care Center in Nashville, Tennessee. In addition to providing specialized HIV medical care, the Comprehensive Care Center provides psychiatric care, case management, nutritional evaluation, on-site infusion/transfusion, and obstetrics and colposcopy services. It also coordinates mental health services and substance abuse treatment programs. In addition to the Center located in Nashville, there are three associated satellite clinics in rural Middle Tennessee. Clinical data were entered directly into an electronic medical record, either by medical providers at the time of the patient encounter, by automated data upload (e.g., laboratory results), or through entry by clinic personnel (e.g., deaths). Electronic and hard copy of medical records were reviewed for ascertainment of substance abuse history from free text provider notes and by ICD-9 and keyword searches. The study cohort was composed of patients receiving care at the Comprehensive Care Center between January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2004, with follow-up through December 31, 2005. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Vanderbilt University.

Definitions and outcomes

Patients were characterized into 3 mutually exclusive groups: 1) IDUs were patients who mentioned injection drug use as HIV risk/probable route of infection or had any mention of IDU in their Comprehensive Care Center medical record; 2) Non-IDUs were patients who had a history of non-injection drug use (e.g., crack cocaine, methamphetamine, heavy alcohol, or poly-drug use), but no history of injection drug use. Non-IDUs were considered to have a history of non-injection drug use if one of the following was present in the Comprehensive Care Center medical record: a diagnosis of substance abuse and/or dependence, notation by the provider of concern about drug or alcohol use, notation of a patient entering a drug or alcohol rehabilitation program, or indication of medical, legal, or social problems resulting from drug or alcohol use. Heavy alcohol was defined as having multiple drinks per day which affected their normal daily lives [16], or having an ICD-9 diagnosis of alcohol abuse. Patients with both injection and non-injection drug use were grouped as IDUs; and 3) Non-users were persons who had no record of any substance use. To account for potential weakness in the pertinence of history of drug use to disease progression, we also conducted chart review to assess active drug use between January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2005, during which outcome variables were ascertained.

HAART was defined as ≥ 7 days use of a regimen containing: 1) at least 2 nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) in combination with at least 1 protease inhibitor (PI) and/or 1 non-NRTI (NNRTI); 2) at least 3 NRTIs; or 3) at least 3 antiretroviral agents of any class.

A study event was defined as either an AIDS-defining event (ADE) or death due to any cause during the study period. ADEs were identified on the basis of 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classification criteria [17], excluding diagnoses based on CD4 cell counts<200 cells/mm3. Patients who did not experience a study event were followed in the cohort either until the end of the study period (December 31, 2005) or until they were lost to follow-up (defined as failing to visit the clinic for 18 months; their last clinic visit was used as a censor date in this case).

Statistical analyses

Sociodemographic and disease characteristics were compared across the three drug use groups by chi-square tests for categorical variables and by Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. To assess the associations between injection and non-injection drug use and HIV disease progression, three Cox proportional hazards models were fitted using the following outcomes as the event of interest, respectively: 1) ADE, 2) death, and 3) ADE or death. Because substance abuse may be associated with a delay in HAART initiation, we performed separate analyses using time from first clinic visit to event for the entire clinic cohort, and using time from initiation of HAART to event among the subgroup who were HAART-naïve at their first clinic visit and initiated their first HAART during the study period. All Cox model analyses were adjusted for age, race, sex, prior antiretroviral therapy (ART), baseline CD4 cell count (expanded using restricted cubic splines to avoid linearity assumptions), and baseline plasma HIV-1 RNA level. These variables were chosen for inclusion in the models a priori, based on findings in the literature or previous studies in the same cohort [18-19]. Analyses were also performed using active drug use instead of history of drug use as the primary predictor variable. All analyses were performed using R statistical software, version 2.11.1 (www.r-project.org).

Results

Sociodemographic and disease characteristics

Of 1,712 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 262 had a history of injection drug use, 785 had a history of non-injection drug use, and 665 were non-users. The median age of this cohort was 38 years (range, 18-82 years), 24% were female, 38% were African-American and 56% were white. Of the study patients, 14% had received non-HAART treatment (such as single or dual antiretroviral regimens) and 33% had been on HAART prior to their first study visit, and an additional 40% (n=687) initiated their first HAART during the study period. IDUs (31%) were less likely than non-users (44%) and non-IDUs (40%) to initiate first HAART during the study (P<0.01). The median follow-up time of the entire cohort was 2.1 years (interquartile range [IQR] of 1.1-3.5 years). HAART-naïve patients who initiated HAART did so after a median of 42 days after study entry. Median time of follow-up among the subgroup who initiated first HARRT was 3 years. IDUs were older than non-IDUs and non-users, and African-Americans were more likely to be IDUs. Non-users were more likely to be female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the HIV-positive study cohort by drug use

| Characteristic | IDUs (n=262) | Non-IDUs (n=785) | Non-users (n=665) | Total cohort (n=1712) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), years | 41 (20-60) | 37 (18-68) | 37 (18-82) | 38 (18-82) | <0.01 |

| Race (n=1703), n (%) | 0.17 | ||||

| White | 134 (51.1) | 452 (57.8) | 370 (56.1) | 956 (56.1) | |

| Nonwhite | 128 (48.9) | 330 (42.2) | 289 (43.9) | 747 (43.9) | |

| African American | 120 (45.8) | 307 (39.3) | 216 (32.8) | 643 (37.8) | |

| Hispanic | 6 (2.3) | 17 (2.2) | 43 (6.5) | 66 (3.9) | |

| Otherb | 2 (0.8) | 6 (0.8) | 30 (4.6) | 38 (2.2) | |

| Female sex | 60 (23%) | 167 (21%) | 188 (28%) | 415 (24%) | 0.01 |

| HAART exposure prior to first visit date | 90 (34%) | 244 (31%) | 225 (34%) | 559 (33%) | 0.4 |

| Non-HAART ART exposure prior to first visit date | 39 (15%) | 92 (12%) | 103 (15%) | 234 (14%) | 0.09 |

| Baseline absolute CD4 at study entry, median (IQR), cells/mm3 (n=1696) | 320 (144-520) | 324 (170-528) | 324 (160-504) | 324 (164-513) | 0.9 |

| Baseline %CD4 at study entry, median (IQR), cells/mm3 (n=1696) | 22 (12-31) | 21 (13-30) | 21 (13-29) | 21 (13-30) | 0.6 |

| Baseline HIV-1 RNA at study entry, median (IQR), log10 copies/mL (n=1701) | 4.4 (2.9-5.0) | 4.4 (3.3-5.0) | 4.3 (2.9-5.0) | 4.4 (3.1-5.0) | 0.5 |

| Initial first HAART during study | 81 (31%) | 314 (40%) | 292 (44%) | 687 (40%) | <0.01 |

| Medium time from study entry to HAART initiation (IQR), days (n=687) | 46 (16-218) | 42 (16-162) | 36 (14-108) | 42 (14-147) | 0.3 |

| Medium follow-up after HAART initiation to death (IQR), years (n=687) | 3.0 (1.8-4.5) | 2.7 (1.7-4.9) | 3.2 (1.8-4.7) | 3.0 (1.8-4.8) | 0.9 |

| CD4+ cell count at initiation of HAART, median (IQR), cells/mm3 (n=673) | 226 (87-322) | 200 (72-317) | 247 (100-347) | 220 (88-328) | 0.06 |

| CD4+ cell percentage at initiation of HAART, median (IQR), cells/mm3 (n=673) | 16% (10-24%) | 16% (8-23%) | 17% (10-25%) | 16% (9-24%) | 0.2 |

| Plasma HIV-1 RNA at initiation of HAART, median (IQR), log10 copies/mL (n=675) | 4.9 (4.5-5.2) | 4.9 (4.4-5.5) | 4.8 (4.2-5.4) | 4.8 (4.4-5.4) | 0.3 |

IDUs=injection drug users; IQR= interquartile range; HAART = highly-active antiretroviral therapy; ART=antiretroviral therapy.

Chi square tests are used for categorical variables and ANOVA tests are used for continuous variables.

Includes Asian, Asian-Pacific Islander, and mixed race.

At baseline (first clinic visit), the median CD4 cell count in the entire study cohort was 324 cells/mm3 and CD4 cell percentage was 21%; median HIV-1 RNA was 4.4 log10 copies/mL; there were no statistically significant differences for those measurements among the three groups of drug use. Among the subgroups of HAART initiators, CD4 cell count was 220 cells/mm3, CD4 cell percentage was 16%, and HIV-1 RNA were 4.8 log10 copies/mL at HAART initiation. Non-users tended to have higher CD4 cell counts (P=0.06) (Table 1).

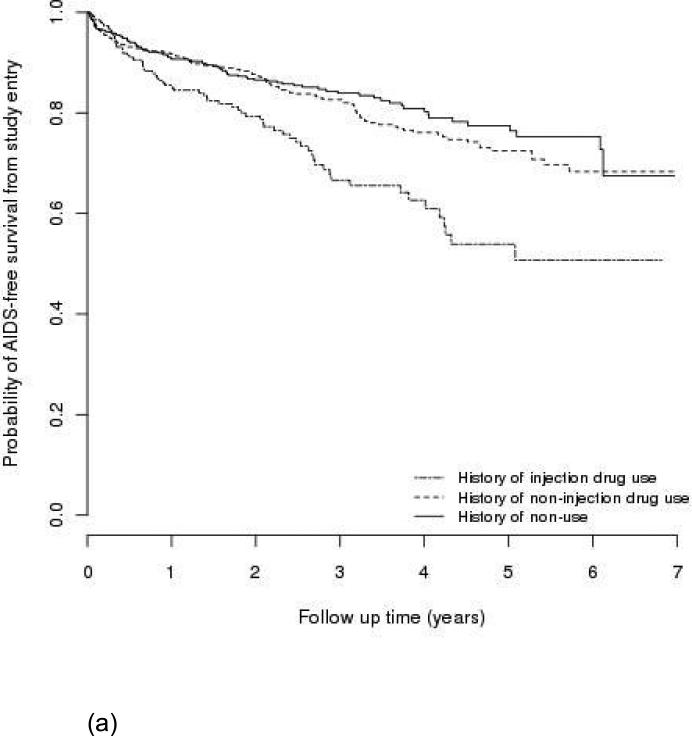

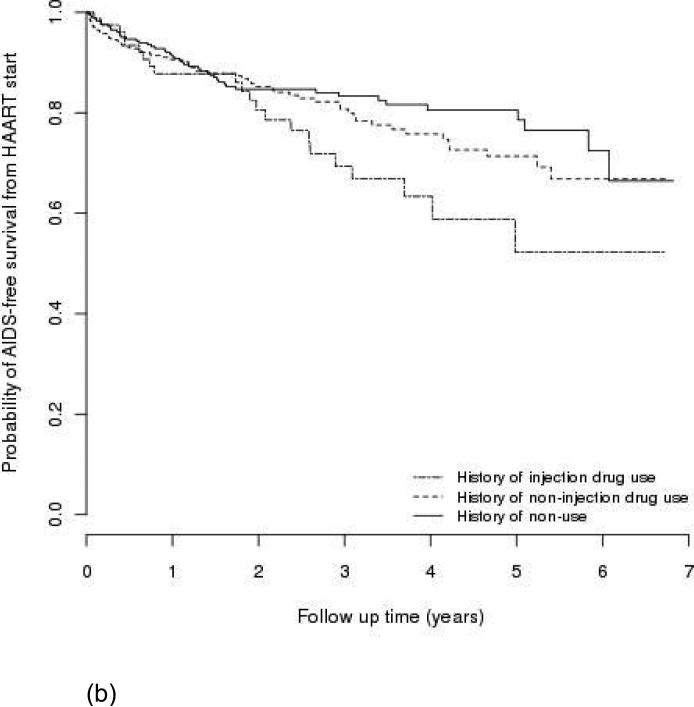

AIDS-free survival

One-hundred eighty patients had an AIDS-defining event during follow-up, and 183 patients died. Among them, 57 patients had developed AIDS before they died. Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier estimates of AIDS-free survival by type of drug use (a) from study entry in the entire cohort and (b) from HAART initiation in the subgroup who initiated first HAART during the study period. IDUs had a lower AIDS-free survival rate than non-users (P<0.01 for (a); P=0.03 for (b)); non-IDUs were not statistically different from non-users (P=0.41 for (a); P=0.35 for (b)). The probabilities of AIDS-free survival one year after entry into the clinic in the entire cohort were approximately 85%, 92%, and 91% for IDUs, non-IDUs, and non-users, respectively.

Figure 1.

AIDS-free survival by type of drug use, (a) in the entire cohort (n=1,712); (b) in subgroup who initiated first HAART during the study period (n=687).

Risk for progression to AIDS-defining event or death by drug use

In multivariate Cox regression models adjusted for sex, age, race, prior ART exposure, HAART use at study entry, baseline CD4 cell count and HIV-1 RNA, non-IDUs showed no statistically significant difference in progression to AIDS or death when compared to non-users (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.19; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92-1.56; P=0.19) (Table 2). IDUs had a 97% higher risk of progression to AIDS or death than non-users, and the difference was statistically significant (HR=1.97; 95% CI=1.43-2.70; P<0.01). Other statistically significant predictors for more rapid progression to AIDS or death were older age (HR=1.41 per 10 years; 95% CI=1.24-1.61), a lower baseline CD4 cell count (e.g., 100 versus 200 cells/mm3, 1.46, 1.30-1.63), and a higher baseline HIV-1 RNA level (per one log change of log10 copies/mL, 1.28, 1.10-1.48) (Table 2). Compared with non-IDUs, IDUs had an increased risk of death (HR=1.83; 95% CI=1.26-2.65; P<0.01), but no higher risk of progression to AIDS (HR=1.19; 95% CI=0.78-1.82; P=0.41) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox regression model for predictors of progression to AIDS-defining event (ADE) or death since study entry among 1,712 HIV-infected patients

| Covariate | ADE (n=176c) | Death (n=176c) | AIDS or Death (n=296c) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Drug use | ||||||

| Non- users | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| Non-injection drug users | 1.17 (0.84-1.63) | 0.35 | 1.30 (0.92-1.85) | 0.14 | 1.19 (0.92-1.56) | 0.08 |

| Injection drug usersa | 1.40 (0.90-2.17) | 0.14 | 2.38 (1.58-3.57) | <0.01 | 1.97 (1.43-2.70) | <0.01 |

| Male sex | 0.79 (0.55-1.14) | 0.21 | 0.72 (0.51-1.03) | 0.07 | 0.82 (0.62-1.09) | 0.17 |

| Age, per 10 years | 1.24 (1.05-1.47) | 0.01 | 1.54 (1.30-1.82) | <0.01 | 1.41 (1.24-1.61) | <0.01 |

| White race | 1.05 (0.77-1.43) | 0.76 | 0.76 (0.56-1.04) | 0.09 | 0.96 (0.76-1.23) | 0.77 |

| Prior ART (any vs. none) | 1.06 (0.69-1.64) | 0.79 | 1.08 (0.70-1.68) | 0.72 | 1.12 (0.80-1.56) | 0.51 |

| On HAART at study entry | 1.40 (0.87-2.26) | 0.16 | 1.18 (0.72-1.92) | 0.51 | 1.21 (0.83-1.75) | 0.32 |

| CD4 cell countsb, cells/mm3 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||

| 100 | 1.51 (1.30-1.76) | 1.41 (1.22-1.63) | 1.46 (1.30-1.63) | |||

| 200 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| 350 | 0.57 (0.49-0.66) | 0.68 (0.58-0.78) | 0.63 (0.57-0.71) | |||

| 500 | 0.36 (0.27-0.48) | 0.56 (0.45-0.70) | 0.48 (0.40-0.57) | |||

| HIV-1 RNAb, log10 copies/mL (per one log increase) | 1.34 (1.11-1.63) | <0.01 | 1.27 (1.05-1.54) | 0.01 | 1.28 (1.10-1.48) | <0.01 |

HR=hazards ratio; CI=confidence interval; ART=antiretroviral therapy.

When comparing with non-injection drug users, HRs and CIs are as follows: 1.19 (0.78, 1.82), P=0.41; 1.83 (1.26, 2.65), P<0.01; 1.65 (1.23, 2.22), P<0.01.

The first values upon or after entry to the study.

Events for patients included in the final model.

Among HAART initiators (n=687), there was no association between non-IDUs and non-users regarding progression from HAART initiation to AIDS (HR=0.95 when compared to non-users; 95% CI=0.57-1.56; P=0.83), though non-IDUs had an increased risk of progression to death (Table 3). Similar to the analysis in the entire cohort, the subgroup analysis found a statistically significant association between IDUs (versus non-users) and progression to AIDS or death (HR=1.83; 95% CI=1.09-3.06).

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox regression model for predictors of progression to AIDS-defining event (ADE) or death since initiation of HAART among 687 patients who initiated first HAART during the study

| Covariate | ADE (n=75c) | Death (n=72c) | AIDS or Death (n=122c) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Drug use | ||||||

| Non-users | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| Non-injection drug users | 0.95 (0.57-1.56) | 0.83 | 1.92 (1.22-3.30) | 0.02 | 1.21 (0.81-1.80) | 0.35 |

| Injection drug usersa | 1.56 (0.81-3.01) | 0.13 | 2.10 (1.02-4.32) | 0.04 | 1.83 (1.09-3.06) | 0.02 |

| Male | 0.96 (0.55-1.68) | 0.88 | 0.66 (0.38-1.15) | 0.14 | 0.80 (0.53-1.23) | 0.31 |

| Age, per 10 year | 1.29 (1.00-1.68) | 0.05 | 1.52 (1.17-1.97) | <0.01 | 1.44 (1.18-1.76) | <0.01 |

| Race (white vs. nonwhite) | 1.04 (0.65-1.66) | 0.87 | 0.87 (0.54-1.41) | 0.57 | 1.11 (0.77-1.61) | 0.57 |

| Prior ART | 1.29 (0.58-2.87) | 0.54 | 1.09 (0.48-2.49) | 0.83 | 1.13 (0.59-2.14) | 0.72 |

| CD4 cell countb, cells/mm3 | <0.01 | 0.02 | <0.01 | |||

| 100 | 1.57 (1.22-2.02) | 1.35 (1.05-1.74) | 1.47 (1.21-1.79) | |||

| 200 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| 350 | 0.74 (0.60-0.90) | 0.75 (0.60-0.93) | 0.73 (0.62-0.87) | |||

| 500 | 0.72 (0.45-1.15) | 0.63 (0.36-1.10) | 0.67 (0.45-0.98) | |||

| HIV-1 RNAb, log10 copies/mL (per one log increase) | 1.33 (0.93-1.89) | 0.11 | 1.13 (0.81-1.59) | 0.47 | 1.14 (0.87-1.49) | 0.33 |

HR=hazards ratio; CI=confidence interval; HAART=highly active antiretroviral therapy; ART=antiretroviral therapy.

When comparing with non-injection drug users, HRs and CIs are as follows: 1.65 (0.84, 3.16), P=0.13; 1.09 (0.57, 2.10), P=0.79; 1.51 (0.92, 2.48), P=0.10.

Values are the ones closest prior to the time point of initiating HAART.

Events for patients included in the final model.

Active Drug Use

Table 4 compares the classifications of history of drug use and active drug use reported during the study period. Seventy-four patients had active IDU during 1999-2005, 768 active non-IDU, and 870 no drug use; a quarter (25%, 67/262) of patients with a history of IDU had reported active injection drug use during the study period, and over four fifths of patients (81%, 638/758) with a history of non-IDU reported active non-IDU. Kaplan-Meier curves and results from multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were similar when history of drug use variables were replaced with active drug use variables. Active injection drug use was associated with an increased risk of AIDS/death (adjusted HR=1.90, 95% CI 1.18-3.08, P<0.01); active non-injection drug users did not differ with non-users when evaluating AIDS/death (HR=1.05, 95% CI 0.84-1.34, P=0.66). Analyses limited to HAART initiators looking at time from HAART initiation until AIDS or death yielded similar results (IDU vs. non-users: adjusted HR=2.19, 95% CI 0.92-5.18, P=0.07; non-IDU vs. non-users: adjusted HR=1.10, 95% CI=0.77-1.59, P=0.60). Patients with a history of injection drug use had poor rates of AIDS-free survival, regardless of whether they had no active drug use or only active non-injection drug use reported during the study period (data not shown).

Table 4.

Classifications of historical and active drug use among 1,712 HIV-infected patients

| History of drug use | Active drug use: 1999-2005 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDU | non-IDU | No use | Total | |

| IDU | 67 | 130 | 65 | 262 |

| non-IDU | 7 | 638 | 140 | 785 |

| No use | 0 | 0 | 665 | 665 |

| Total | 74 | 768 | 870 | 1712 |

Discussion

This study is the first to assess the association of both history of non-injection drug use and history of injection drug use on HIV disease progression in the same cohort. Consistent with previous reports, we found that history of IDU was a strong risk factor for progression to AIDS or death [7, 12, 18, 20-21]. Persons in our cohort with a history of non-IDU were not statistically different from non-users when evaluating HIV disease progression. These general trends were seen when we studied rates of AIDS/death from first visit among all patients presenting for care and when we limited analyses to rates of AIDS/death after HAART initiation. These trends also held when we only considered active drug use reported during the study period.

Prior studies of non-injection drug use and HIV disease progression had mixed findings [8-9, 14-15]. Some studies reported more rapid disease progression among HIV-infected drug users that was associated with late HIV diagnosis, or lack of access or delayed access to HAART [2, 12], either because drug users had adverse socioeconomic problems such as poor housing situation or co-morbidities such as mental illness [22], or because physicians were less likely to recommend HAART for IDUs despite indication for therapy due to concerns regarding poor adherence and possible transmission of multidrug-resistant HIV [23-24]. Our data did not suggest that drug users (either IDUs or non-IDUs) entered clinical care later than non-users, as there were no differences in baseline CD4 cell count and HIV-1 RNA level. However, our study did show that more non-users and non-IDUs initiated HAART than IDUs in our study clinic, even though there was no difference of HAART exposure prior to first visit to the clinic (Table 1).

Our non-injection drug users are comprised of patients with a wide variety of drug-use behaviors, both in terms of frequency and types of drugs used. This diversity makes our results more difficult to interpret and might have contributed to the negative findings. Results were similar when we considered active non-injection drug use, although this variable is subject to similar limitations. Studies that prospectively collect data on types of drugs, activity, and frequency of use are warranted. Meanwhile, injection drug use has been consistently shown to be predictive of poor HIV outcomes.

Our study has other limitations. First, we did not include information on cause of death, as it is difficult to ascertain AIDS-related causes from non-AIDS-related causes. Many deaths may be unrelated to AIDS, as both injection and non-injection drug use is associated with increased non-AIDS mortality in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected cohorts [25-30]. This might explain our observation that non-IDU among HAART initiators was positively associated with death but not with AIDS. Second, we did not have data on HAART adherence, which could be a confounding factor in the relationship between drug use and HIV disease progression.

Our study has several strengths. The relatively large sample size permitted evaluation in both the entire clinic cohort and those HAART initiators. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the associations between history of injection and non-injection drug use and HIV disease progression in the same cohort. We found that IDUs had more rapid disease progression compared with non-users, while non-IDUs appeared to have no effect on disease progression. We hypothesize that IDUs could have a longer drug use history and poorer general health status, or that a larger dose of drug intake via injection may lead to poorer HAART adherence, but these hypotheses need to be verified in future studies. Given the paucity of publications on this topic, we believe more studies are needed to assess the association between active non-injection drug use and HIV disease progression, also taking into consideration adherence to HAART, pattern and type of drug use, and other potential confounding socio-demographic and behavioral factors.

Our findings have implications for clinical care. Because non-injection drug use is common in HIV-infected patients, clinicians should consider drug and alcohol abuse screening among AIDS patients at their regular clinic visits, and quickly link patients with these problems to drug treatment programs. Clinicians should pay special attention to injection drug users, as our study and many others have identified worse outcomes in this subgroup. However, we believe it is also important to provide drug screening and treatment to non-IDUs. Drug treatment is likely to improve HIV disease treatment outcomes either through reducing the direct effect of drug abuse or through other mechanisms such as enhancing HAART adherence.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by NIH grants P30 AI 54999 and K24 AI065298. We thank David Weinstein, Sally Bebawy, Vlada Melekhin, Asghar Kheshti, Daniel Rasbach, Stephen Raffanti, and William Wester for their participation in the discussions of data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hogg R, Lima V, Sterne JA, et al. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372:293–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PG, et al. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. JAMA. 1998;280:547–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spire B, Lucas GM, Carrieri MP. Adherence to HIV treatment among IDUs and the role of opioid substitution treatment (OST). Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:262–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucas GM, Cheever LW, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Detrimental effects of continued illicit drug use on the treatment of HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:251–9. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinkin CH, Barclay TR, Castellon SA, et al. Drug use and medication adherence among HIV-1 infected individuals. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:185–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorpe LE, Frederick M, Pitt J, et al. Effect of hard-drug use on CD4 cell percentage, HIV RNA level, and progression to AIDS-defining class C events among HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1423–30. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000127354.78706.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore RD, Keruly JC, Chaisson RE. Differences in HIV disease progression by injecting drug use in HIV-infected persons in care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35:46–51. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook JA, Burke-Miller JK, Cohen MH, et al. Crack cocaine, disease progression, and mortality in a multicenter cohort of HIV-1 positive women. AIDS. 2008;22:1355–63. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830507f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Franco MJ, Sheppard HW, Hunter DJ, Tosteson TD, Ascher MS. The lack of association of marijuana and other recreational drugs with progression to AIDS in the San Francisco Men's Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:283–9. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palepu A, Tyndall M, Yip B, O'Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS, Montaner JS. Impaired virologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy associated with ongoing injection drug use. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:522–6. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grigoryan A, Hall HI, Durant T, Wei X. Late HIV diagnosis and determinants of progression to AIDS or death after HIV diagnosis among injection drug users, 33 US States, 1996-2004. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lert F, Kazatchkine MD. Antiretroviral HIV treatment and care for injecting drug users: An evidence-based overview. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:255–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapadia F, Cook JA, Cohen MH, et al. The relationship between non-injection drug use behaviors on progression to AIDS and death in a cohort of HIV seropositive women in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy use. Addiction. 2005;100:990–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, Sales S, Page B, Campa A. Crack-cocaine use accelerates HIV disease progression in a cohort of HIV-positive drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:93–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181900129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, et al. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:377–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abel EL, Kruger ML, Friedl J. How do physicians define “light,” “moderate,” and “heavy” drinking? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:979–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulgan T, Shepherd BE, Raffanti SP, et al. Absolute count and percentage of CD4 cell counts are independent predictors of disease progression in HIV-infected persons initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:425–31. doi: 10.1086/510536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raffanti SP, Fusco JS, Sherrill BH, et al. Effect of persistent moderate viremia on disease progression during HIV therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1147–54. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000136738.24090.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egger M, May M, Chêne G, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:119–29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.May M, Sterne JA, Sabin C, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients up to 5 years after initiation of HAART: collaborative analysis of prospective studies. AIDS. 2007;21:1185–97. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328133f285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrando SJ, Wall TL, Batki SL, Sorensen JL. Psychiatric morbidity, illicit drug use and adherence to zidovudine (AZT) among injection drug users with HIV disease. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1996;22:475–87. doi: 10.3109/00952999609001674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor PG, Selwyn PA, Schottenfeld RS. Medical care for injection-drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:450–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408183310707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding L, Landon BE, Wilson IB, Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Cleary PD. Predictors and consequences of negative physician attitudes toward HIV-infected injection drug users. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:618–23. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orti RM, Domingo-Salvany A, Munoz A, Macfarlane D, Suelves JM, Anto JM. Mortality trends in a cohort of opiate addicts, Catalonia, Spain. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:545–53. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.3.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fugelstad A, Annell A, Rajs J, Agren G. Mortality and causes and manner of death among drug addicts in Stockholm during the period 1981-1992. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;96:169–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb10147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyndall MW, Craib KJ, Currie S, Li K, O'Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Impact of HIV infection on mortality in a cohort of injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28:351–7. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200112010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quaglio G, Talamini G, Lechi A, Venturini L, Lugoboni F, Mezzelani P. Study of 2708 heroin-related deaths in north-eastern Italy 1985-98 to establish the main causes of death. Addiction. 2001;96:1127–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96811276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degenhardt L, Hall W, Warner-Smith M. Using cohort studies to estimate mortality among injecting drug users that is not attributable to AIDS. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(Suppl 3):56–63. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.019273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribeiro M, Dunn J, Sesso R, Dias AC, Laranjeira R. Causes of death among crack cocaine users. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28:196–202. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462006000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]