Abstract

Biotin synthesis requires the C7 α, ω-dicarboxylic acid, pimelic acid. Although pimelic acid was known to be primarily synthesized by a head to tail incorporation of acetate units, the synthetic mechanism was unknown. It has recently been demonstrated that in most bacteria the biotin pimelate moiety is synthesized by a modified fatty acid synthetic pathway in which the biotin synthetic intermediates are O-methyl esters disguised to resemble the canonical intermediates of the fatty acid synthetic pathway. Upon completion of the pimelate moiety, the methyl ester is cleaved. A very restricted set of bacteria have a different pathway in which the pimelate moiety is formed by cleavage of fatty acid synthetic intermediates by BioI, a member of the cytochrome P450 family.

The BioC-BioH pathway of pimelate synthesis

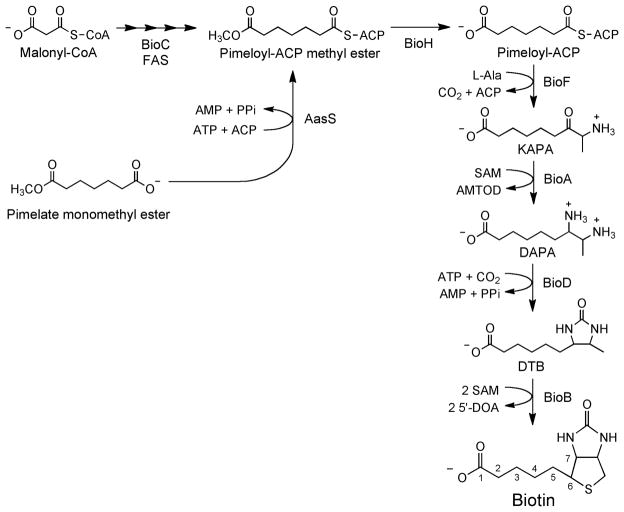

A long-standing puzzle in the synthesis of the key metabolic cofactor, biotin, was the source of pimelate moiety that contributes carbons 1 through 7 of biotin (Fig. 1). Pimelic acid (heptanedioic acid) has long been known to be a biotin precursor because it bypassed the biotin requirement of Corynebacterium diphtheriae [1,2] and stimulated biotin synthesis in certain bacteria and fungi. Moreover, radioactively labeled pimelate was incorporated into biotin [3]. The earliest known biotin precursor that could be isolated from culture media was 7-keto-8-amino-pelargonic acid (KAPA) (Fig. 1) and M. Eisenberg had the insight that KAPA synthesis could proceed from L-alanine and pimeloyl-CoA by a mechanism analogous to the synthesis of δ-aminolevulinic acid from glycine and succinyl-CoA. Eisenberg synthesized pimeloyl-CoA and showed that it was a substrate for KAPA synthase (BioF), which catalyzes KAPA synthesis, the first intermediate in assembly of the fused heterocyclic rings of biotin [4]. Later NMR analyses of 13C-labeled biotin isolated from E. coli cultures grown in the presence of 13C-labeled acetate species showed that the C-3, C-5, and C-7 carbon atoms of biotin are derived from C-1 of acetate whereas C-2 of acetate contributes carbon atoms C-2, C-4, and C-6 [5–7]. The labeling pattern indicated that the pimeloyl moiety was formed by head to tail incorporation of three intact acetate units as is the case in fatty acid (and polyketide) synthesis with a molecule of CO2 providing C-1. Since the biotin C-1 and C-7 atoms showed different labeling patterns, free pimelic acid (a symmetrical molecule) was not a biotin biosynthetic intermediate. Hence, the pimeloyl moiety must be assembled with one of the carboxyl groups covalently linked to another moiety, such as CoA or acyl carrier protein (ACP). Moreover, the labeling patterns eliminated other plausible sources such as the tryptophan, lysine or diaminopimelic acid synthetic pathways or via elongation of 2-oxoglutarate [6]. Hence, the question of how to assemble the pimeloyl-thioester remained unanswered.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of biotin synthesis in E. coli. The late steps of the pathway are shown, as is the bypass of BioC function by AasS-catalyzed formation of pimeloyl-ACP methyl ester in vivo or in vitro. See Figs. 2 and 3 for delineation of the modified fatty acid pathway engendered by BioC-catalyzed methylation of malonyl-CoA. Abbreviations: SAM, S-adenosyl methionine; KAPA, 7-keto-8-amino-pelargonic acid; DAPA, 7,8-diaminopelargonic acid; DTB, dethiobiotin; AMTOD, S-adenosyl-2-oxo-4-methylthiobutyric acid; SAH, S-adenosyl homocysteine; 5′-DOA, 5′-deoxyadenosine.

The extensive genetic analysis of the E. coli biotin biosynthetic pathway gave only two candidates as possible pimeloyl moiety synthetic genes, bioC and bioH [8]. These genes had been placed early in the pathway because the biotin requirement of bioC and bioH mutant stains was satisfied by each of the intermediates that accumulated in the culture media of mutant strains blocked in known steps of the pathway. Moreover, neither bioC nor bioH strains accumulated intermediates that fed any other mutant strain and thus the order in which the two genes acted in the pathway was unknown. The lack of cross feeding between bioC and bioH strains suggested that the intermediates accumulated by these mutants might be protein bound. In the >40 years since their discovery no clear hypothesis for the functions of the BioC and BioH protein had emerged. Indeed, it had been argued that BioH was not involved in pimelate synthesis [9] and also that it was intimately involved [10]. In the latter scheme [10] BioC was postulated to catalyze the Claisen condensations required to assemble the pimelate chain whereas BioH was an acyltransferase that transferred the pimeloyl moiety from a putative BioC active site thiol to CoA. A more recent proposal was that BioH would somehow condense CoA and pimelic acid to form pimeloyl-CoA perhaps with the help of BioC [11] although no pimelate source was proposed. The conundrum was that neither the BioC nor BioH proteins seemed to have the ability to assemble pimelate chains. BioC was annotated as an S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase whereas BioH had been shown to have esterase activity on a series of short and medium chain acyl p-nitrophenyl esters [11,12] and on the methyl ester of dimethylbutyryl-S-methyl mercaptopropionate [13]. Although an esterase (perhaps acting as an acyltransferase in the presence of the cognate acceptor) could be fit into several of the pathways proposed, there seemed no need for a methyltransferase. Biotin contains no methyl groups and the origins of all of the biotin carbon atoms had been traced and none originated from methionine [5,6]. This perplexing situation aside, it seemed that enzymes from another biosynthetic pathway were needed to assemble the pimelate carbon chain and the roles of BioC and BioH would be to permit this other pathway to function in biotin synthesis. In 1963 Lynen and coworkers [14] suggested that pimeloyl-CoA was formed by the enzymes of fatty acid synthesis. The proposed pathway was consistent with the 13C-labeling studies and stipulated that three molecules of malonyl-CoA would be condensed with the primer malonyl moiety retaining the carboxyl group introduced by acetyl-CoA carboxylase fixation of CO2. The other two malonyl-CoA molecules would lose their free carboxyl groups in the course of the two decarboxylative Claisen reactions required to give the C7 dicarboxylate. This proposal received belated support from the discovery that type III polyketide synthases catalyze similar condensation reactions [7,15]. However, in polyketide synthesis the keto groups are retained or remodeled whereas pimelate synthesis requires that the keto groups become fully reduced. Lynen and coworkers proposed that the sequential reduction-dehydration-reduction steps of fatty acid synthesis could eliminate the keto groups [14] (these reactions were proposed to occur on CoA thioesters since ACP had not been discovered). However, this seemed unlikely to occur because the crystal structures available for essentially the full set of E. coli fatty acid biosynthetic proteins show that all sequester the acyl chain in strongly hydrophobic tunnels or clefts. Hence, the charged free ω-carboxyl group of the Lynen intermediates would have to enter unfavorable environments in order to access the active sites of the fatty acid biosynthetic enzymes. In confronting this dilemma a plausible hypothesis emerged that would explain how BioC and BioH would allow the fatty acid biosynthesis machinery to tolerate the type of intermediates proposed in the Lynen pathway.

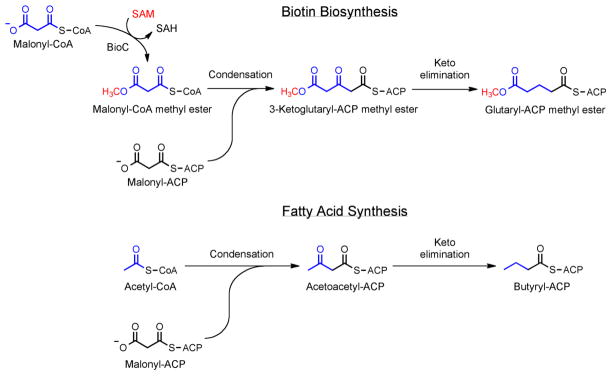

In this hypothesis [8] BioC would convert the free carboxyl group of a malonyl thioester (probably malonyl-CoA) to its methyl ester (Fig. 2). Methylation would both cancel the charge of the carboxyl group and provide a methyl carbon that would mimic the methyl ends of normal acyl chains. This methylated species would then have properties (chain length, hydrophobicity) that approximate those of the substrates normally accepted by the enzymes of fatty acid synthesis (e.g., propionyl-CoA). Two cycles of the standard elongation-reduction-dehydration-reduction cycle of fatty acid synthesis would result in the acyl carrier protein (ACP) thioester of monomethyl pimelate. The methyl ester of this intermediate must be cleaved because the carboxyl is needed to form the amide linkage that attaches biotin to the metabolic enzymes where it performs its key metabolic roles [16]. It therefore followed that cleavage would be the job of the BioH esterase and give pimeloyl-ACP. This in turn would react with L-alanine in the BioF reaction to give KAPA, the first intermediate in assembly of the fused rings of biotin. In this scenario, introduction of the methyl ester would disguise the biotin synthetic intermediates such that they would be accepted as substrates by the fatty acid synthetic pathway. When synthesis of the pimeloyl moiety is complete and disguise is no longer needed, the methyl group would be removed.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the initiation steps in biotin synthesis and fatty acid synthesis. FabH, the 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthetase that catalyzes the initiation step of fatty acid synthesis, is believed to also catalyze the initiation step of biotin synthesis based on the sensitivity of in vitro DTB synthesis to thiolactomycin and the requirement of FabH for a CoA primer.

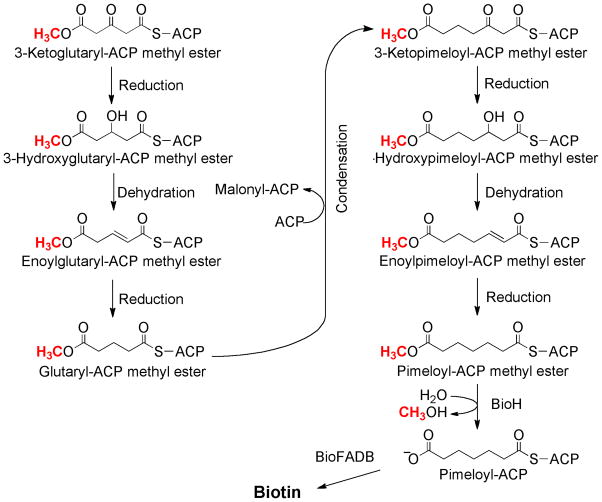

The proposed pathway was tested both in vivo and in vitro. In both cases a key tool was the acyl-ACP synthetase (AasS) of Vibrio harveyi [17,18] (Fig. 1). This enzyme catalyzes the ATP-dependent ligation of fatty acids to ACP in a reaction analogous to that of acyl-CoA synthetases. Indeed, AasS is closely related to a medium chain acyl-CoA synthetase [17]. The model postulated that the methyl ester of pimeloyl-ACP was an intermediate in biotin synthesis. The monomethyl ester of pimelate was synthesized and found to be an excellent substrate for AasS whereas pimelic acid had no detectable substrate activity (as expected from the hydrophobic acyl chain binding site of AasS) [17]. This result suggested that monomethyl pimelate supplementation of the medium of biotin requiring strains expressing AasS might allow growth in the absence of biotin. Since the methyl group was already in place, pimeloyl-ACP methyl ester was expected to bypass the need for BioC, but not the need for BioH (which would be required to cleave the ester). Indeed, monomethyl pimelate allows growth of a bioC knockout strain, but not of a bioH knockout strain, and growth required AasS expression [19]. Moreover, the monomethyl esters of malonate and glutarate show the same pattern, both compounds support AasS-dependent growth of the bioC strain, but not that of the bioH strain. The growth response is specific in that the monomethyl esters of the C4, C6, C8, C9 and C11 α, ω-dicarboxylic acids fail to support growth of either biotin-requiring strain [19]. Growth is also supported by putative intermediates in the pathway (Fig. 3) such as 3-ketoglutaric acid monomethyl ester, but not by closely related compounds that should not be intermediates (e.g., 2-ketoglutaric acid monomethyl ester) [19].

Fig. 3.

The postulated intermediates of pimeloyl-ACP methyl ester synthesis. All of the C5 intermediates and most of the C7 intermediates have been shown to bypass the biotin requirement of bioC knockout strains that express AasS. Pimeloyl-ACP is an effective substrate for BioF although the enzyme can also utilize pimeloyl-CoA.

The next step was to develop an in vitro system in which dethiobiotin (DTB) would be synthesized de novo. DTB was assayed rather than biotin to avoid BioB, a notoriously unstable S-adenosyl methionine radical enzyme that inserts the biotin sulfur atom [8]. Dialyzed cell free extracts of wild type E. coli strains synthesized DTB when the extracts were supplemented with the precursors required for fatty acid and DTB synthesis (de novo fatty acid synthesis in such extracts was demonstrated many years ago, but this seems the first example of in vitro coupling of the biotin synthetic enzymes). Extracts of bioC and bioH strains made no DTB under these conditions, but DTB synthesis did proceed upon addition of the missing enzyme in purified form [19]. In extracts of a bioC knockout strain the BioC requirement was bypassed when the extracts were supplemented with the methyl esters of malonyl-ACP, glutaryl-ACP or pimeloyl-ACP [19]. Glutaryl-ACP, the C5 compound lacking the methyl ester function, was inactive showing that the presence of a ω-carboxyl group prevented access to the fatty acid synthetic pathway. The in vitro system was also used to show that KAPA synthesis required S-adenosyl methionine and that inhibitors of fatty acid synthesis or methyl transfer blocked DTB synthesis [19].

There are two “loose ends” in the published work on the BioC-BioH pathway. First, protein solubility problems prevented a direct demonstration that BioC is a malonyl-CoA O-methyltransferase. This has now been remedied (Lin and Cronan, manuscript in preparation). The second loose end is that BioH is a rather promiscuous hydrolase that also cleaves the ethyl, propyl and butyl esters of pimeloyl-ACP plus glutaryl-ACP methyl ester, although it is unable to cleave the thioester bond of these substrates. Others have reported that BioH cleaves the methyl ester of dimethylbutyryl-S-methyl mercaptopropionate [13] and a series of short and medium chain acyl p-nitrophenyl esters [11,12]. This promiscuity may reflect indications that E. coli BioH may have recently recruited for biotin synthesis and has not been fully integrated into the biotin synthetic pathway. The E. coli bioH gene differs from the other genes in the pathway in that it is neither located within the bio operon nor regulated by the BirA repressor/biotin protein ligase [20,21]. This is in contrast to many other bacteria where bioH resides within the biotin operon and is generally located immediately upstream of bioC [22]. Thus, the E. coli bioH gene may encode a protein that is less specific than those encoded by the more “domesticated” bioH genes. Note that the BioH function seems something of a “wild card” among biotin synthetic enzymes since in some bacteria the gene has been displaced from its site upstream of bioC by other genes [22] that seem likely to encode hydrolases.

The BioI pathway of pimelate synthesis

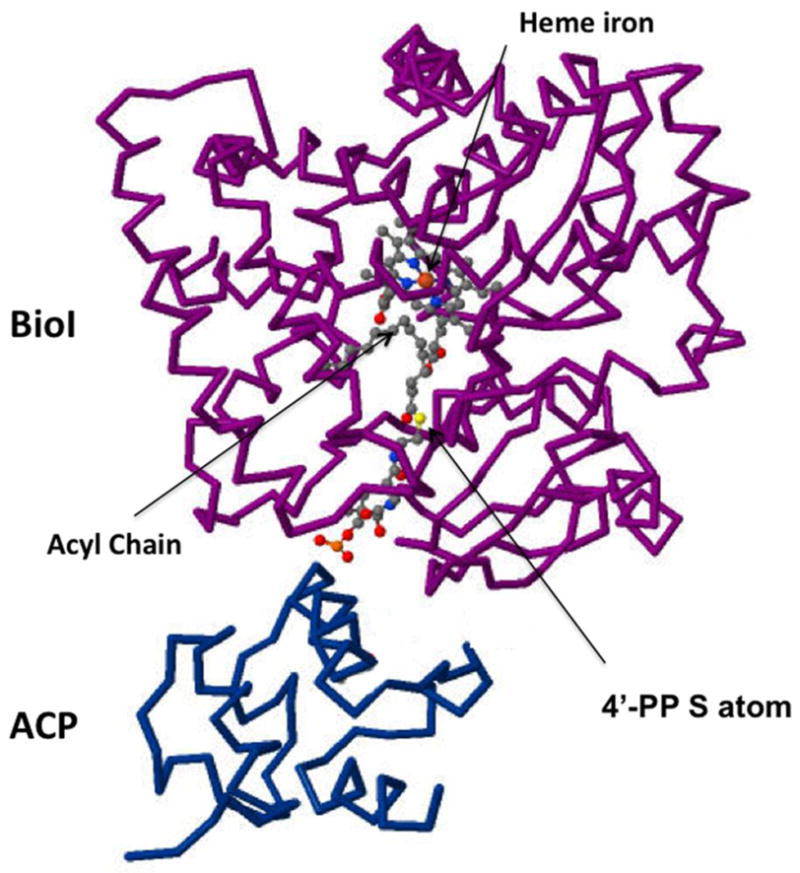

A second pathway of pimelate synthesis is found in Bacillus subtilis and its close relatives. These bacteria lack BioC and BioH and are believed to synthesize pimeloyl-ACP by an O2-dependent cleavage of long chain acyl-ACPs [23]. The acyl-ACP cleavage reaction is catalyzed by BioI, a heme protein that contains the canonical cytochrome P450 fold [24]. Early work using free fatty acids as BioI substrates gave pimelic acid but also a variety of other products [25]. Much better specificity was obtained with acyl-ACP substrates [26] presumably because ACP-BioI interactions restricted the motion of the acyl chain within the active site. This prediction has recently been borne out by elegant crystal structures of complexes of BioI with various acyl-ACPs [24,27]. These structures show the covalently bound ACP phosphopantetheine prosthetic group and the attached acyl chain are inserted into a hydrophobic binding pocket within BioI (Fig. 4). Within this pocket the fatty acyl chain is held in a highly kinked U-shaped conformation in which carbon atoms C7 and C8 are located 4–5 Å from the heme iron. Thus, the specific production of pimeloyl-ACP is dictated by the geometry of the active site plus interactions along the acyl chain, the length of the phosphopantetheine linker and the BioI-ACP interface. Cleavage of a hydrocarbon chain is an unusual reaction for a cytochrome P450 and is thought to proceed by successive hydroxylations of the C7 and C8 carbon atoms followed by cleavage of the resulting vicinal diol [28,29]. Thus, rather than performing a single oxidation cycle, BioI holds the acyl chain for several oxidation cycles in which the product of the prior oxidation becomes the substrate of the next oxidation until the chain is cleaved and the products are released. It should be noted that BioI is rarely encoded in bacterial genomes. Indeed, most Bacilli (e.g., B. cereus, B. anthracis, B. thuringiensis) use the E. coli BioC-BioH pathway.

Fig. 4.

The structure of BioI complexed with tetradecanoyl-ACP [24]. The protein backbones are shown together with the acyl chain (gray beads), the heme Fe atom (orange sphere) and the sulfur atom (yellow sphere) of the 4′-phosphopantetheine (4′-PP) prosthetic group which is in thioester linkage with the acyl chain. The figure was made from PDB file 3EJB using Jmol.

Conclusions and future prospects

The two known pathways of pimelate synthesis are both dependent on fatty acid synthesis, but at different levels. The BioC-BioH pathway proceeds by using the normal fatty acid synthetic pathway to make an abnormal fatty acid. In this pathway methyl ester formation has some commonality with the protective groups used in organic synthesis in that both are removed when the synthesis is complete. However, protective groups prevent undesired reactions whereas he methyl group facilitates the reactions required for pimelate synthesis. The BioI pathway intercepts fatty acid synthetic intermediates, acyl-ACPs, that are destined for incorporation into complex lipids (e.g., phospholipids) and performs oxidative cleavage of the acyl chains. Both pathways are expensive, the BioC-BioH pathway consumes S-adenosyl methionine whereas BioI requires electrons from NAD(P)H to reduce the ferric heme iron to the ferrous state. However, the bioenergetic considerations seem of little importance because only trace amounts of biotin are needed for growth (E. coli can grow with ~100 molecules/cell). More important is that the BioI pathway seems to lock the bacterium into an aerobic life style whereas the BioC-BioH pathway is active under both aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions.

A final consideration is the “chicken or egg” conundrum. Synthesis of the pimelate moiety of biotin requires fatty acid synthesis. However fatty acid synthesis requires biotin because acetyl-CoA carboxylase is a biotin-dependent enzyme [30] required for synthesis of malonyl-CoA, the building block of fatty acid synthesis. So how then did the present pathways get started? One possibility is that another enzyme originally made malonyl-CoA, perhaps an enzyme similar to carbamyl phosphate synthetase.

Acknowledgments

Work from this laboratory was supported by grant AI15650 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.du Vigneaud V, Dittmer K, Hague E, Long B. The growth-stimulating effect of biotin for the diphtheria bacillus in the absence of pimelic acid. Science. 1942;96:186–187. doi: 10.1126/science.96.2486.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller JH. Pimelic acid as a growth accessory for the Diphtheria bacillus. J Biol Chem. 1937;119:121–131. doi: 10.1126/science.85.2212.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg MA. The incorporation of 1,7 14C pimelic acid into biotin vitamers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1962;8:437–441. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(62)90292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg MA, Star C. Synthesis of 7-oxo-8-aminopelargonic acid, a biotin vitamer, in cell-free extracts of Escherichia coli biotin auxotrophs. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:1291–1297. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.4.1291-1297.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ifuku O, Miyaoka H, Koga N, Kishimoto J, Haze S, Wachi Y, Kajiwara M. Origin of the carbon atoms of biotin. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:585–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Sanyal I, Lee S, Flint DH. Biosynthesis of pimeloyl-CoA, a biotin precursor in Escherichia coli, follows a modified fatty acid synthesis pathway: 13C-labeling studies. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:2637–2638. This paper and that immediately above demonstrated that C2–C6 of the E. coli pimelate moiety was made by head to tail condensations of acetate units with C1 coming from CO2. Together these papers eliminate many possible pathways of pimelate synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseng CC, McLoughlin SM, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT. Role of the active site cysteine of DpgA, a bacterial type III polyketide synthase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:970–980. doi: 10.1021/bi035714b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Cronan JE. Biotin and lipoic acid: synthesis attachment and regulation. In: Böck A, Curtiss RI, Kaper JB, Karp PD, Neidhardt FC, Nyström T, Slauch JM, Squires CL, editors. EcoSal—Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press; 2006. http://www.ecosal.org. This review discusses the E. coli biotin synthetic pathway in detail and proposed the current model of the BioC-BioH pathway. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Regan M, Gloeckler R, Bernard S, Ledoux C, Ohsawa I, Lemoine Y. Nucleotide sequence of the bioH gene of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:8004. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.19.8004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemoine Y, Wach A, Jeltsch JM. To be free or not: the fate of pimelate in Bacillus sphaericus and in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:645–647. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.t01-4-442924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Sanishvili R, Yakunin AF, Laskowski RA, Skarina T, Evdokimova E, Doherty-Kirby A, Lajoie GA, Thornton JM, Arrowsmith CH, Savchenko A, et al. Integrating structure, bioinformatics, and enzymology to discover function. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26039–26045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303867200. This paper describes the crystal structure of E. coli BioH and shows BioH to be a serine esterase. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon MA, Kim HS, Oh JY, Song BK, Song JK. Gene cloning, expression, and characterization of a new carboxylesterase from Serratia sp. SES-01: comparison with Escherichia coli BioHe enzyme. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;19:147–154. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0804.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13•.Xie X, Wong WW, Tang Y. Improving simvastatin bioconversionin Escherichia coli by deletion of bioH. Metab Eng. 2007;9:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2007.05.006. This paper illustrates the promicuity of E. coli BioH. The authors found hydrolysis of an ester linkage in a precursor being fed to a manipulated E. coli strain and showed that BioH was the responsible esterase. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Lezius A, Ringelmann E, Lynen F. Zur biochemischen Funktion des Biotins. IV. Die Biosynthese des Biotins. Biochem Z. 1963;336:510–525. This paper put forth the hypothesis that the fatty acid synthetic pathway was responsible for pimelate synthesis. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin MB, Izumikawa M, Bowman ME, Udwary DW, Ferrer JL, Moore BS, Noel JP. Crystal structure of a bacterial type III polyketide synthase and enzymatic control of reactive polyketide intermediates. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45162–45174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman-Smith A, Cronan JE., Jr The enzymatic biotinylation of proteins: a post-translational modification of exceptional specificity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:359–363. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y, Chan C, Cronan JE. The soluble acyl-acyl carrier protein synthetase of Vibrio harveyi B392 is a member of the medium chain acyl-CoA synthetase family. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10008–10019. doi: 10.1021/bi060842w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Y, Morgan-Kiss RM, Campbell JW, Chan CH, Cronan JE. Expression of Vibrio harveyi acyl-ACP synthetase allows efficient entry of exogenous fatty acids into the Escherichia coli fatty acid and lipid A synthetic pathways. Biochemistry. 2010;49:718–726. doi: 10.1021/bi901890a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19••.Lin S, Hanson RE, Cronan JE. Biotin synthesis begins by hijacking the fatty acid synthetic pathway. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:682–688. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.420. This paper reports the delineation of the BioC-BioH pathway both in vivo and in vitro. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barker DF, Campbell AM. Use of bio-lac fusion strains to study regulation of biotin biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:789–800. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.789-800.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koga N, Kishimoto J, Haze S, Ifuku O. Analysis of the bioH gene of Escherichia coli and its effect on biotin productivity. J Ferment Bioeng. 1996;81:482–487. [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Rodionov DA, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS. Conservation of the biotin regulon and the BirA regulatory signal in Eubacteria and Archaea. Genome Res. 2002;12:1507–1516. doi: 10.1101/gr.314502. This paper is the only large scale bioinformatics study of biotin synthesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bower S, Perkins JB, Yocum RR, Howitt CL, Rahaim P, Pero J. Cloning, sequencing, and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis biotin biosynthetic operon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4122–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4122-4130.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24••.Cryle MJ, Schlichting I. Structural insights from a P450 carrier protein complex reveal how specificity is achieved in the P450(BioI) ACP complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15696–15701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805983105. This paper reports several high resolution crystal structures of BioI in complexes with acyl-ACPs having different acyl chains. These are an unusually instructive structures. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green AJ, Rivers SL, Cheeseman M, Reid GA, Quaroni LG, Macdonald ID, Chapman SK, Munro AW. Expression, purification and characterization of cytochrome P450 Biol: a novel P450 involved in biotin synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6:523–533. doi: 10.1007/s007750100229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Stok JE, De Voss J. Expression, purification, and characterization of BioI: a carbon-carbon bond cleaving cytochrome P450 involved in biotin biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;384:351–360. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2067. This paper reports the first evidence that the physiological substrates od bioI are acyl-ACPs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27•.Cryle MJ. Selectivity in a barren landscape: the P450(BioI)-ACP complex. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:934–939. doi: 10.1042/BST0380934. This review compares BioI with other cytochrome P450s that oxidize fatty acids. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cryle MJ, De Voss JJ. Carbon-carbon bond cleavage by cytochrome p450(BioI)(CYP107H1) Chem Commun (Camb) 2004:86–87. doi: 10.1039/b311652b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cryle MJ, Matovic NJ, De Voss JJ. Products of cytochrome P450(BioI) (CYP107H1)-catalyzed oxidation of fatty acids. Org Lett. 2003;5:3341–3344. doi: 10.1021/ol035254e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cronan JE, Jr, Waldrop GL. Multi-subunit acetyl-CoA carboxylases. Prog Lipid Res. 2002;41:407–435. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(02)00007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]