Abstract

How self tolerance is maintained during B cell development in the bone marrow has been a focal area of study in immunology. Receptor editing, anergy and clonal deletion all play important roles in the regulation of autoimmunity in the immature population. The mechanisms of tolerance induction in the periphery, however, are less well characterized. Overexpression of the apoptosis inhibitor Bcl-2 rescues autoreactive B cells from deletion and can contribute to the development of autoimmune disease in certain genetic backgrounds. Using a peptide induced autoimmunity model, we recently identified a peripheral tolerance checkpoint in antigen-activated B cells that have undergone class switching and somatic hypermutation. At this checkpoint, receptor editing, induced by antigen engagement, dampened the autoantibody response. In this study, we show that receptor editing fails to be induced in antigen activated DNA-reactive B cells that overexpress Bcl-2 (Bcl-2 Tg). The failure to induce RAG and receptor editing is likely due, at least partially, to the lack of self antigen. First, the levels of circulating DNA and of apoptotic bodies in the spleen of Bcl-2 Tg mice are significantly lower than in control mice. Second, in Bcl-2 Tg mice, RAG can be induced in a population of antigen-activated B cells by providing exogenous soluble antigen. These data suggest that, in addition to its anti-apoptotic activity, Bcl-2 may indirectly inhibit tolerance induction in B cells acquiring anti-nuclear antigen reactivity after peripheral activation by limiting the availability of self antigen.

1. Introduction

The repertoire of B cell antigen receptors (BCR) is generated through rearrangement of the immunoglobulin (Ig) variable (V), diversity (D) and joining (J) gene segments, a process mediated by the recombination activating gene (RAG) complex. V(D)J rearrangement, while generating great diversity, is random and can result in nonfunctional gene products or receptors with unwanted reactivity. B cells are susceptible to tolerance induction by antigen stimulation prior to maturation to immunocompetence [1]. This tolerance induction maintains a peripheral B cell population that is largely free of self-reactive clones [2, 3]. Clonal deletion is a key mechanism for the removal of autoreactivity in B cells, both a primary mechanism [4], and one that follows ineffective receptor editing, [5] and increased resistance to apoptosis has been implicated in the development of autoimmune disease.

The anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 was identified as a result of its dysregulated expression in human follicular lymphomas [6-8]. Bcl-2 is expressed at a high level in pro-B cells and naïve mature B cells and downregulated in pre-B cells, immature B cells and germinal center (GC) B cells, stages at which negative selection occurs [9]. The constitutive overexpression of Bcl-2 in a B cell specific manner has been shown to impair tolerance induction in a number of models [10-13], and can lead to the development of a lupus-like serology with anti-nuclear reactivity [14-16]. Similarly, the targeted disruption of Bim, a Bcl-2 family member that interacts with Bcl-2 and promotes apoptosis, also results in the development of a lupus-like autoimmune syndrome with production of anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) [17]. Collectively, these observations suggest that increased resistance to apoptosis is a risk factor for lupus-like autoimmunity.

At the immature stage, B cells reactive to self antigen in the bone marrow continue to express RAG and undergo secondary V(D)J rearrangement, or receptor editing, at the Ig V gene locus, leading to the generation of a new BCR with a non-autoreactive specificity [18, 19]. Receptor editing was initially thought to be a relatively rare event whose contribution to tolerance was minor compared to clonal deletion [20-22]. More recent studies, however, suggest that receptor editing may in fact be a dominant mechanism for the maintenance of tolerance in immature B cells [23-25]. Only when receptor editing fails to remove the autoreactive BCR, does the B cell initiate an apoptotic pathway [23]. It is now well appreciated that tolerance mechanisms also need to operate during and after the GC response when the BCR undergoes a second wave of diversification through somatic hypermutation. We and others have shown that somatic mutation routinely generates potentially pathogenic autoreactivity in response to bacterial antigen or hapten [10, 26]. With the emerging recognition of the importance of receptor editing in shaping the naive B cell repertoire, its role in the mature population has been revisited. Reports have demonstrated that receptor editing may be re-induced in mature B cells within GCs [27-30]. Alt and colleagues have more recently shown that receptor editing occurs in B cells after the transitional II stage and can faciliate tumor formation [31, 32]. We reported the expression of RAG by mature, autoreactive early memory B cells in mice that were immunized with a peptide mimetope of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) [33, 34]. The induction of RAG is dependent on the presence of self antigen and requires IL-7 receptor signaling [34]. Receptor revision in these antigen-activated B cells leads to Igλ expression and effectively diminishes the autoreactive antibody response [34]. Because overexpression of Bcl-2 has been shown to promote receptor editing in immature B cells in the bone marrow, and inhibits clonal deletion of autoreactive B cells in the periphery [35], we asked whether Bcl-2 overexpression would disturb tolerance mechanisms in autoreactive B cells following antigen activation.

In this report, we demonstrate that in mice with a B cell specific overexpression of Bcl-2 (Bcl-2 Tg), RAG is not induced in the post-GC autoreactive B cell population following immunization with the peptide mimetope of dsDNA. Bcl-2 overexpression decreases the amount of circulating DNA and diminishes apoptotic cells in the spleen of immunized mice. Administration of exogenous antigen, however, is able to induce RAG expression in antigen-activated B cells. Collectively, these data suggest that lack of self antigen may be responsible for the failure to induce receptor editing in antigen activated autoreactive B cells. This study reveals a novel effect of Bcl-2 in the regulation of peripheral B cell tolerance, that is, dampening receptor editing by limiting the presence of self (nuclear) antigen that is required for triggering expression of RAG proteins.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice and Immunizations

Six to eight weeks old female BALB/c mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed in accord with AAALAC regulations. BALB/c × RAG2:GFP mice were generated as previously described [33]. BALB/c × E Bcl-2.22 mice (Bcl-2 Tg) [14] were maintained by backcrossing to BALB/c. RAG2:GFP × Bcl-2 mice were generated by crossing RAG2:GFP+/- with Bcl-2+/- mice, both on a BALB/c background. μMT mice on a (C57BL/6 × 129/Sv) background were obtained from K. Rajewsky (Cologne, Germany) [36] and backcrossed to the BALB/c strain for seven to nine generations. Mice received 100 μg of DWEYSVWLSN peptide on a branched poly-lysine backbone (“DWEYS-MAP”, AnaSpec, San Jose, CA) or ADGSGGRDEMQASMWS conjugated to KLH (10-2–KLH; AnaSpec) intraperitoneally on day 0 in a 1:1 emulsion of complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). On day 7, mice were boosted with 100 μg DWEYS-MAP or 10-2-KLH in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA, Difco Laboratories). In order to examine whether soluble antigen induces RAG expression in antigen-activated B cells, 1 mg of soluble 10-2–BSA or BSA was injected i.v. into 10-2–KLH–immunized mice on days 14, 15, and 16 after the primary challenge.

2.2. Adoptive Transfer

BALB/c or Bcl-2 Tg mice were immunized with DWEYS-MAP as described above. μMT mice were immunized with DEWYS-MAP two weeks before adoptive transfer. Spleens from BALB/c or Bcl-2 Ig mice were harvested on day 21 following immunization. B cells were purified by using the mouse B cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). In order to remove plasma cells, anti-mouse CD138-biotin was added to the antibody cocktail. 107 of purified splenic B cells cells/mouse were injected i. v. into peptide primed MT mice. Recipient mice were boosted the next day following cell transfer.

2.3. Tetramer Generation

DWEYSVWLSN-streptavidin-allophycocyanin (DWEYS-APC) tetramers, and DWEYSVWLSN-streptavidin-AlexaFluor488 (DWEYS-A488) tetramers were generated as previously described [37]. Biotinylated peptide was synthesized by AnaSpec. Streptavidin-APC and streptavidin-AlexaFluor488 was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

2.4. Reagents and flow cytometry

Mice were sacrificed and spleens were harvested on the specified date and placed in cold Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 0.3% fetal calf serum (HBSS/FCS). Single cell suspensions were made by grinding spleens on a 40 m cell strainer. The following anti-mouse antibodies were used for flow cytometry analysis: PerCP-anti-B220 (clone RA3–6B2, BD Pharmingen), APC-DWEYS tetramer was used to detect antigen-binding B cells. 4'-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was added before flow cytometry to exclude dead cells. Erythrocytes were lysed in 0.17M NH4Cl, pH 7.4. Cells were stained in HBSS/2% FCS at 4°C for 60 minutes. Data were acquired by using LSRII flow cytometry (BD Bioscience) and analyzed by using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.).

2.5. ELISA

ELISA plates (Costar, Corning, NY) were coated with 15 μg/ml DWEYS-MAP or 150 μg/ml sonicated, filtered calf-thymus DNA (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Plates were blocked with 3% FCS. Serum antibody was detected following washing in PBS-Tween 20 with 1 μg/ml anti-mouse-IgG-AP (goat polyclonal, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) in PBS/1% BSA. Plates were washed and binding was measured by addition of 1 mg/ml PNPP (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and read at 405 nm on a Titertek Multiskan Plus.

2.6. Cell Sorting

To sort the tetramer binding populations, splenocytes were prepared from 4-5 mice at day 16 after immunization. T cells, monocytes and dendritic cells were depleted as previously reported [33]. Staining was performed as described above. Immediately after sorting, cells were resuspended in Trizol (Invitrogen) and frozen at –80°C until RNA isolation. Sorting was performed on a FACSAria Flow Cytometer (BD Bioscience).

2.7. Histology

Spleens were removed on day 16 or 17 after the first immunization and frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN) by immersion in a 2-methylbutane bath on dry ice. Sections were cut using a Leica CM1900 cryostat. Prior to staining, sections were warmed to room temperature and rehydrated in PBS followed by blocking for 30 minutes with 3% FCS. Staining was performed in 3% FCS plus 0.3% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Tetramer staining was performed at room temperature for 1 hour or at 4°C overnight. Slides were washed in PBS and mounted in Aqua-Poly/Mount (Polysciences, Inc, Warrington, PA). Fluorescent microscopy was performed on an AxioCam II microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging). Image acquisition was performed with a Hamamatu ORCA-ER camera using the Openlab imaging software (Improvision). The following antibodies were used: anti-RAG2 (rabbit polyclonal, BD Pharmingen), PE-anti-B220 (RA3-6B2, Pharmingen). Anti-RAG antibodies were detected using Zenon Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen).

2.8. TUNEL Staining

Fresh-frozen spleen sections were obtained as described above. TUNEL staining was performed following protocols in user bulletin of TACS® 2 TdT-Fluor In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (4812-30-K, Trevigen). Image acquisition was performed with a Hamamatu ORCA-ER camera using the Openlab imaging sorfware (Improvision). One third of the spleen was harvested for tissue fixation, staining and counting of TUNEL positive cells. The spleen was frozen and 5μ sections were taken randomly through the specimen. The sections were then randomly chosen for mounting on slides and the slides were randomly chosen for analysis. Complete sections were visualized (5X) and digitized under comparable exposure conditions. The images were analyzed in an automated program for detection of the target – TUNEL positive cells (Zeiss, Axio-Imager, Thornwood, NY). Size and segmentation rules were constant for target detection across all samples. Additionally, a counting frame of fixed dimension was randomly placed within the borders of the section and only the targets within the frame were counted. In this manner tunel positive cell density was determined for the BCL-2 (N=3, sections =30, all measurements in duplicate) and WT (N=3, sections =51, all measurements in duplicate).

2.9. qPCR

RNA was isolated from sorted cells using TriZol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Random hexamer primed RT-PCR was performed on 5 μl RNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) in a final volume of 100 μl. qPCR was performed using an ABI 7900 (Applied Biosystems Inc.) and analyzed using SDS 2.2. ABI TaqMan Gene Expression Assays sets were used, and the reactions performed using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Inc.) in a final volume of 10 μl. Relative template concentration was determined from the standard curve using Cts determined by the SDS software. All primer sets spanned an intron/exon border. ABI Primer IDs: RAG2= Mm00501300_m1, polr2a= Mm00839493_m1.

2.10. Extracellular DNA assay

Blood was collected at day 14 post first immunization and plasma was extracted by spinning at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Plasma DNA level was measured by Quant-iT™ PicoGreen ® dsDNA kit (Invitrogen).

2.11. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in Graphpad Prism v4.02 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA).

3. Results

3.1. Bcl-2 Tg mice generate antigen-specific B cells following immunization with the DWEYS peptide

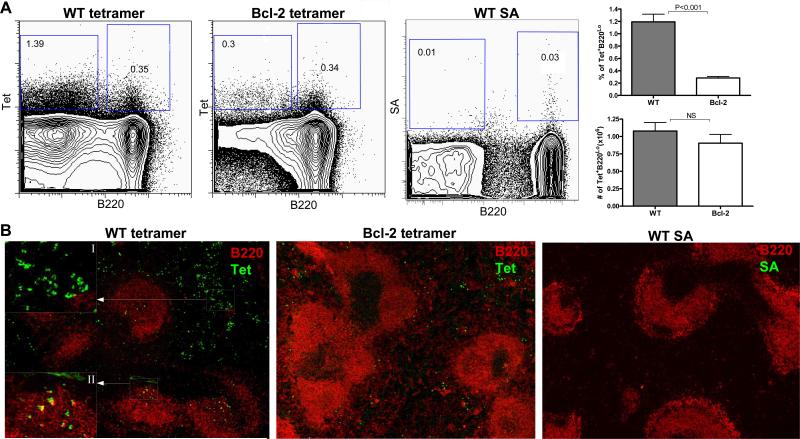

We have previously reported an antigen-induced model of autoimmunity, in which immunization of non-autoimmune BALB/c mice with the DWEYS peptide, a mimetope of DNA, resulted in an autoimmune serology similar to SLE [38]. Antigen-specific B cells in these mice were shown to derive from the GC response and can be identified with a flurochrome-labeled peptide tetramer [37]. Antigen-binding B cells (Tet+) can be divided into two populations: a Tet+B220hi subset and a Tet+B220low subset [33, 34]. These two populations are developmentally linked and B cells progress from the B220hi population of activated B cells to the B220low population of early memory or pre-plasma cells [34]. In this study, we asked whether constitutive overexpression of Bcl-2 rescues DNA-reactive B cells generated through the GC reaction during the response to DWEYS-peptide immunization. Following immunization with the DWEYS peptide, Bcl-2 Tg mice, like wild type (WT) mice, developed both of the B220hi and the B220low populations of Tet+ B cells (Figure 1A). The antigen-reactive B cells were also detected in histological analysis of the spleen sections from immunized mice (Figure 1B). Although the frequency of the Tet+B220low cells was lower in Bcl-2 Tg mice, the number of cells in the early memory compartment was comparable to that in WT littermate controls (Figure 1A). The difference in the frequency may be explained by the fact that Bcl-2 Tg mice contain a larger number of splenic B cells than WT mice [14].

Figure 1. Immunization with DWEYS-MAP induces antigen-specific B cells in Bcl-2 Tg mice.

(A) FACS analysis of tetramer binding cells (left two panels). Splenocytes from immunized WT mice were also stained with unloaded tetramer (streptavidin, SA) as a control (third panel). A representation of the percentage and number of Tet+ B220low is also shown, n=4. (B) Immunohistology for tetramer binding in the spleens of DWEYS immunized mice. Both Tet+B220low (I) and Tet+B220high (II) cells are displayed in the inserts representing enlarged designated areas. Unloaded tetramer (SA) control staining was performed on the spleen of WT mice (right panel). Four to five mice were immunized with DWEYS-MAP in CFA on day 0 and boosted with DWEYS-MAP in IFA on day 7. Spleens were prepared for analysis on day 16 following immunization. The experiment was repeated twice.

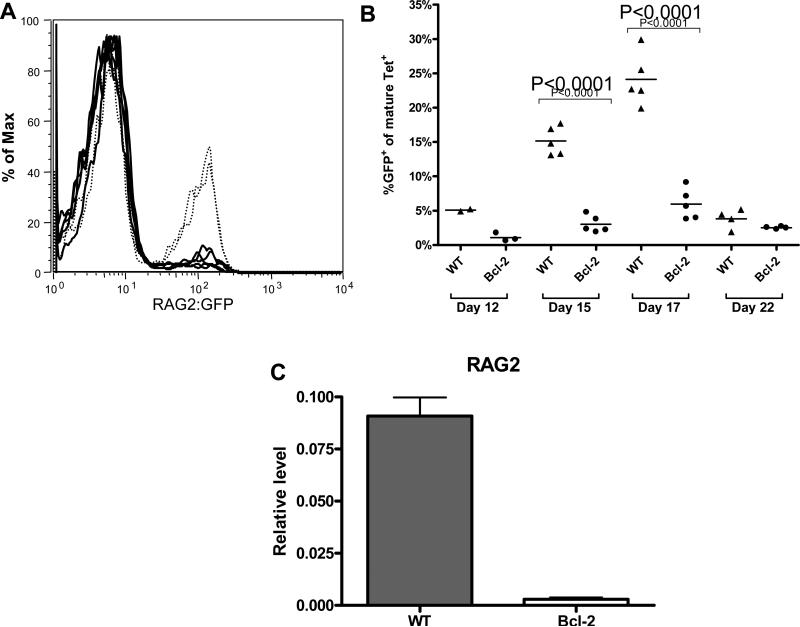

3.2. Constitutive expression of Bcl-2 blocks RAG expression in autoreactive early-memory B cells

Our previous studies demonstrated that in BALB/c mice, receptor editing was induced in antigen-reactive B cells following immunization with the DWEYS peptide and contributed to peripheral tolerance induction [33, 34]. In order to investigate whether overexpression of Bcl-2 modulates the process of receptor revision, we crossed the RAG2:GFP mice with Bcl-2 Tg mice (RAG2:GFP × Bcl-2 Tg) and examined the expression of the RAG2:GFP in antigen-binding B cells. Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that the frequency of GFP+ cells in the antigen-binding population was dramatically decreased in RAG2:GFP × Bcl-2 Tg mice, compared to RAG2:GFP WT mice (Figure 2A). Kinetic experiments confirmed that GFP was expressed in a time-dependent manner in WT mice. Expression of GFP was not induced, rather than delayed, in mice overexpressing Bcl-2, as GFP+ cells were not detected at any time throughout the GC response (Figure 2B). The suppression of RAG in Bcl-2 Tg mice was at the transcriptional level, as qPCR analysis showed a lack of RAG2 mRNA expression in antigen-reactive B cells isolated on day 17 following immunization, when the highest level of RAG was detected in control mice (Figure 2B-C).

Figure 2. Bcl-2 Tg inhibits RAG2 induction in antigen-reactive B cells following DWEYS-peptide immunization.

(A) FACS analysis shows expression of GFP in tetramer positive cells from RAG2:GFP mice (dotted lines) but minimal expression in RAG2:GFPxBcl-2 Tg mice (heavy lines), on day 16 post immunization. (B) Kinetic analysis of RAG2:GFP expression in the spleens from DWEYS-MAP immunized mice shows no expression of RAG in antigen-specific B cells. Triangles, RAG2:GFP; circles, RAG2:GFPxBcl-2 Tg mice. (C) qPCR analysis shows no induction of RAG2 mRNA following immunization in Bcl-2 mice. Mice were immunized with DWEYS-MAP as described and Tet+B220low cells were sorted for qPCR on day 16 following immunization.

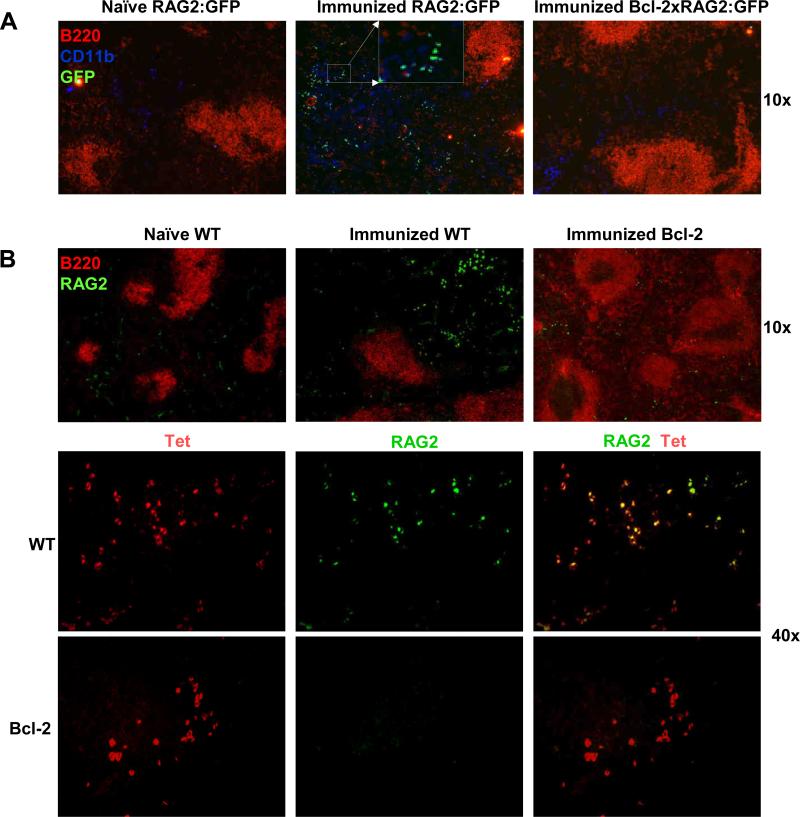

To further confirm the inhibition of RAG induction in Bcl-2 Tg mice, splenic tissue from DWEYS-immunized mice was examined for RAG expression by histology. While naive RAG2:GFP mice showed no expression of GFP in the spleen (Figure 3A), GFP+ B cells were observed in the spleen of DWEYS-immunized mice (Figure 3A), consistent with our previous results [33, 34]. In contrast, we observed a nearly complete absence of GFP expression in the spleen of RAG2:GFP × Bcl-2 mice immunized with DWEYS (Figure 3A). This was further confirmed by direct staining of spleen sections with an anti-RAG2 antibody. As shown in Figure 3B, naïve WT mice did not express RAG2 at detectable levels. The expression of RAG2 was evident in splenic B cells of DWEYS-immunized WT mice (Figure 3B), but not in DWEYS-immunized Bcl-2 Tg mice (Figure 3B). Co-staining with DWEYS-tetramer and anti-RAG2 antibody demonstrated that RAG2 was expressed by Tet+ cells in DWEYS-immunized BALB/c mice, but not Bcl-2 Tg mice (Figure 3B). As reported previously. no tetramer or RAG2 staining was observed in naive BALB/c control mice (data not shown).

Figure 3. Histological analysis of Bcl-2 Tg mice reveals no RAG2 expression.

(A) Splenic histology of naive and immunized RAG2:GFP mice, and immunized RAG2:GFP × Bcl-2. Significant expression of GFP was observed in immunized RAG2:GFP mice but not in immunized RAG2:GFP × Bcl-2 Tg mice. B220 and CD11b were used to show B cell follicles and extrafollicular loci, respectively. Green, GFP; Red, B220; Blue, CD11b. Insert displays the enlarged image of the designated area and shows that GFP+ cells do not co-stain with CD11b. (B) Histological staining of spleen sections from immunized WT and Bcl-2 Tg mice with anti-RAG2 (green) and anti-B220 (red), top panel; or with tetramer (red) and anti-RAG2 (green), middle and bottom panels. Original magnification: A, × 100; B, top and middle, × 100; bottom, × 400. Three to five mice were used in each group. Four to six pictures were taken for each spleen section.

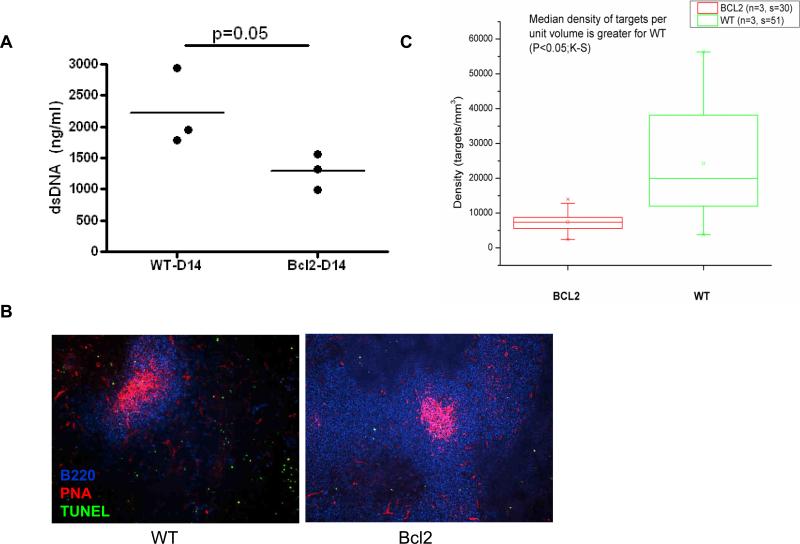

3.3. Overexpression of Bcl-2 diminishes plasma dsDNA level and apoptotic debris in spleen

In BALB/c mice immunized with the DWEYS peptide, the re-induction of RAG in post-GC autoreactive B cells requires the presence of self antigen, dsDNA, as treatment with DNase abrogates the induction of RAG [34]. In vitro studies have shown that Bcl-2 overexpression inhibits cell death and release of DNA from multiple cell lines in culture [39]. Moreover, enforced expression of Bcl-2 in a B cell-specific manner is able to suppress apoptosis at various stages, including the GC stage [40]. It is, therefore, reasonable to speculate that the level of circulating self antigen might be reduced in mice overexpressing Bcl-2 and receptor revision may not be induced due to the lack of sufficient antigen stimulation. To test this hypothesis, we first measured the concentration of plasma DNA in both naïve and peptide immunized mice. There was no significant difference in naive animals between Bcl-2 Tg mice and WT littermates (data not shown). However, on day 14 following DWEYS immunization, Bcl-2 Tg mice had higher levels of dsDNA present in plasma compared to the control group (Figure 4A). Next, we performed a TUNEL assay to determine the level of fragmented DNA and apoptotic cells, a potential source of DNA antigen, in the spleen of immunized mice. The number of TUNEL+ cells in Bcl-2 Tg mice was markedly lower than in control group (Figure 4B, 4C). Taken together, these data suggest that Bcl-2 overexpression diminished the amount of DNA, the self antigen that induces RAG expression in peptide-immunized WT mice, thus abrogating receptor editing in post-activation DNA-reactive B cells.

Figure 4. Overexpression of Bcl-2 diminishes endogenous level of self antigen (DNA).

Mice were immunized with DWEYS-MAP peptide and boosted one week later. Plasma and fresh spleen sections were prepared at day 14 following the first immunization. (A) Plasma dsDNA levels in WT littermates and Bcl-2 Tg mice; (B) Representative image of TUNEL staining of spleen sections and (C) Numeration of apoptotic signals in the spleens.

3.4. Exogenous antigen can induce RAG in Bcl-2 Tg mice

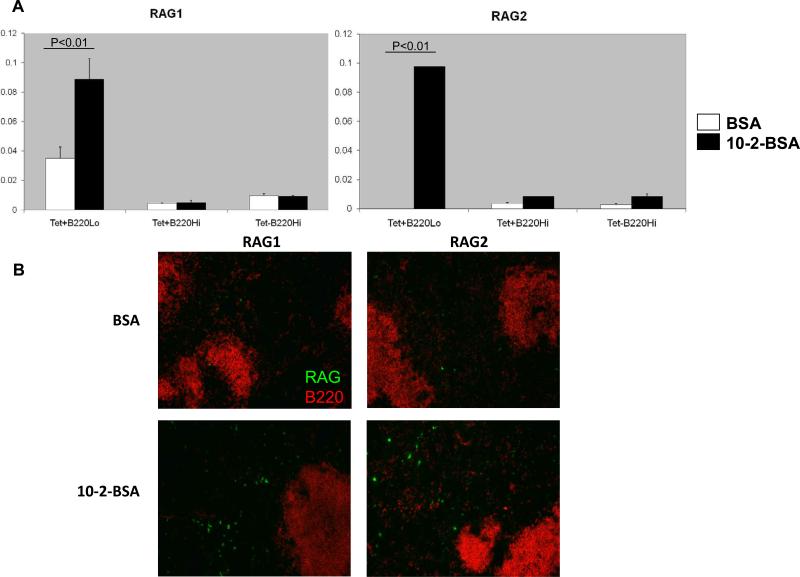

We wanted to confirm that the failure to induce RAG in Bcl-2 Tg mice was indeed due to insufficient antigen stimulation and not to an inability to re-express RAG. We previously demonstrated that in BALB/c mice immunized with the 10-2 peptide, a phosphorylcholine mimetope that does not generate an autoreactive B cell response, RAG could be induced in post-GC B cells by providing exogenous soluble 10-2 [34]. Therefore, we immunized the Bcl-2 Tg mice with the 10-2 peptide, coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin(10-2-KLH). During the GC reaction, we administrated to the mice a soluble form of 10-2-bovine serum albumin (10-2-BSA) to mimic self antigen, or BSA alone as a control. On day 17 following initial immunization, spleens were prepared for analysis of RAG expression. We first performed a qPCR assay for RAG transcripts in FACS-sorted antigen-reactive (Tet+) and nonreactive (Tet-) cells. Similar to the results we observed in BALB/c mice, soluble antigen 10-2-BSA was able to induce both RAG1 and RAG2 in the antigen-binding post-activation B cells (Tet+B220lo) (Figure 5A). Immunohistology staining of spleen sections further confirmed that RAG expression was evident in mice given10-2-BSA (Figure 5B). These observations demonstrated that exogenous soluble antigen could induce RAG in post-activation B cells in Bcl-2 Tg mice. Therefore, the absence of RAG induction in DWEYS peptide immunized Bcl-2 Tg mice is likely to be a result of insufficient self antigen due to the Bcl-2 transgene.

Figure 5. Soluble antigen can induce expression of RAG in Bcl-2 Tg mice immunized with 10-2-KLH.

On days 14, 15 and 16 following immunization with 10-2-KLH, 10-2-BSA or BSA alone was administered i.v. (1mg/mouse). Mice were sacrificed on day 17. 10-2 reactive or non-reactive B cells were isolated, (A) qPCR for RAG1 and RAG2 was performed; (B) histology staining of spleen sections collected on day 17 is shown.

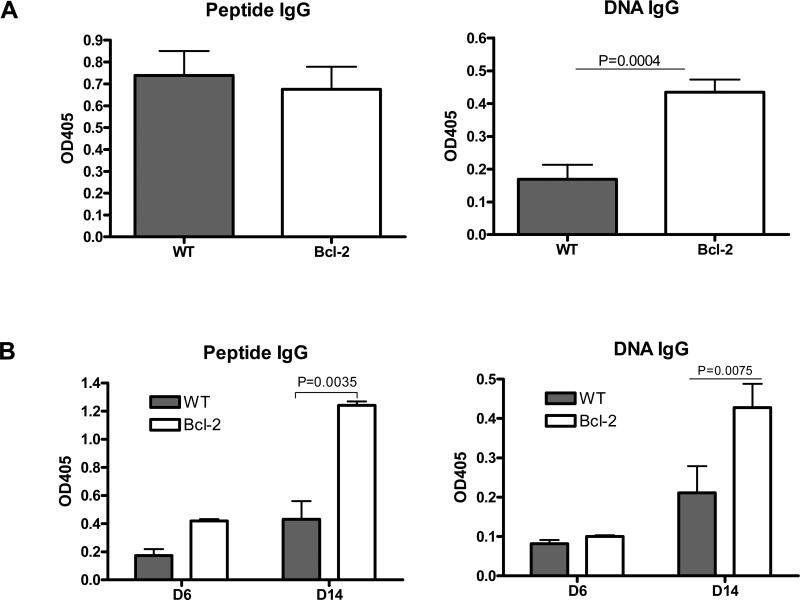

3.5. Overexpression of Bcl-2 increases the anti-dsDNA antibody response

Because overexpresssion of Bcl-2 suppressed receptor editing, we asked whether Bcl-2 overexpression altered the anti-DNA, anti-peptide memory response in DWEYS-MAP immunized mice. To address this question, we performed an adoptive transfer experiment. We first immunized Bcl-2 Tg mice and WT mice with DWEYS-MAP to generate antigen-specific memory B cells. At the same time, we primed Igμ chain mutated (μMT) mice with DWEYS-MAP to generate antigen specific memory T cells [36]. After three weeks, splenic B cells from the immunized mice were purified by using a negative isolation kit; CD138+ plasma cells were also excluded. An equal number of purified B cells from ether immunized Bcl-2 Tg or WT mice were adoptively transferred into primed μMT recipients. The μMT mice were then boosted with DWEYS-MAP to induce a secondary or memory response. Development of anti-DNA and anti-peptide IgG antibodies were measured by ELISA. Both WT and Bcl-2 Tg mice developed anti-DNA and anti-peptide IgG by day 21 following peptide immunization. Prior to harvesting memory B cells, the titers of anti-peptide IgG were similar between Bcl-2 Tg and WT mice, but Bcl-2 overexpressing B cells produced a higher titer of anti-DNA IgG antibodies (Figure 6A). During the memory response, on day 14 following antigen rechallenge, the IgG titers for both peptide and DNA were significantly higher in μMT mice reconstituted with Bcl-2 overexpressing B cells, compared to mice reconstituted with WT B cells (Figure 6B). These data suggest that Bcl-2 overexpression compromised tolerance induction in post-GC B cells and allowed the maturation of DNA-reactive B cells into a functional memory compartment.

Figure 6. Enforced expression of Bcl-2 increased the autoantibody response.

Bcl-2 Tg mice or WT littermates were immunized with DWEYS-MAP on day 0 and boosted on day 7. After four weeks, splenic B cells were isolated and adoptively transferred to antigen-primed μMT mice. CD138+ plasma cells were excluded from the transfer. The recipient mice were boosted once with DWEYS-MAP one day later and sera were collected for ELISA. (A) ELISA of serum IgG antibodies in Bcl-2 Tg and WT mice four weeks following primary immunization. Bcl-2 Tg mice developed higher levels of anti-DNA antibody. (B) ELISA of memory antibody response in recipient mice. Data are the mean ± SEM of 3 to 5 mice in each group.

4. Discussion

Apoptosis is an essential element in the development and homeostasis of the immune system. To achieve immune tolerance, autoreactive lymphocytes must be negatively selected upon encounter with self antigen. One important regulator of lymphocyte survival or death is the Bcl-2 protein family, containing both pro- and anti-apoptotic members, among which Bcl-2 was first described as a proto-oncogene [6-8]. Bcl-2 is expressed at a high level in pro-B cells and resting mature B cells, and downregulated at stages where negative selection occurs, such as the pre-B cell, immature B cell, and GC B cell stages [41, 42]. Following immunization, the plasma cell compartment of Bcl-2 Tg mice is expanded and the duration of the antibody response is a markedly prolonged [14, 43], but the number of memory cells is unaltered. More recently, overexpression of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL was shown to rescue GC B cells from apoptosis and impair selection of V gene-mutated high-affinity B cells into the memory compartment, thus resulting in accumulation of low-affinity clones in the memory B cell pool [40, 44]. Interestingly, generation of high-affinity long-lived plasma cells in the bone marrow was not impaired.

Studying mice bearing the Bcl-2 transgene and a transgene encoding the heavy chain of an anti-dsDNA antibody, R4A, we demonstrated that Bcl-2 was able to promote the survival and maturation of autoreactive B cells, resulting in elevated serum levels of anti-dsDNA antibody [12]. Immunization of Bcl-2 Tg mice with phosphorylcholine did not induce significant anti-dsDNA antibody titers, but cross-reactive anti-PC, anti-dsDNA B cell clones could be isolated by hybridoma technology during the primary but not the secondary response [45]. Similarly, studies of Bcl-2 Tg mice carrying the autoreactive VH3H9 transgene show that overexpression of Bcl-2 extended the lifespan of anti-dsDNA B cells, but did not result in antibody secretion [16]. In contrast to these studies of transgene-expressing B cells, which suggested that autoreactive B cells were excluded from the memory compartment despite Bcl-2 overexpression, studies of the autoreactive response to the hapten arsonate (ars) in Bcl-2 Tg mice have shown that cross-reactive anti-ars, anti-DNA B cells do enter the memory compartment and can be induced to secrete autoantibody [10, 11]. Recently, it has been shown that the sle1 locus from chromosome 1 of NAM2410 mice will also cause an abrogation of tolerance in GC B cells in a similar model. Immunization of C57 Bl/6 sle1 mice expressing an anti-Ars, anti-DNA heavy chain as a knock-in construct with Ars coupled to a protein carrier led to the survival of GC matured and DNA cross-reactive B cells into the memory compartment. Interestingly, these cells harboring the sle1 lupus susceptibility locus over expressed Bcl-2 [46]. Overexpression of Bcl-2 has also been shown to alter somatic hypermutation in some systems [47] but not in others [11], and has been implicated in autoantibody production in an estrogen-modulated model of lupus [48]. The reasons for some discrepancies among these studies are not clear but may be explained by differences in the model systems used, the genetic background of the mice, or the Bcl-2 transgenes used. These data suggest that the ability of Bcl-2 to rescue autoreactive B cells and permit their activation and entry into memory pool is contingent upon multiple factors.

Lang et al. reported that immature and mature autoreactive B cells that overexpress Bcl-2 differ in their response to autoantigen [35]. As expected, the anti-apoptotic property of Bcl-2 resulted in an impairment of clonal deletion in both bone marrow and splenic B cell populations. The immature population activated a compensatory mechanism to maintain tolerance by increasing the frequency of receptor editing. In contrast, mature B cells encountering self antigen in the periphery did not undergo editing, but persisted in the periphery in an untolerized state. Thus, overexpression of Bcl-2 can protect autoreactive B cells from clonal elimination, but plays distinct roles in central and peripheral B cell tolerance.

We recently reported that RAG is re-induced in antigen-activated B cells in BALB/c mice immunized with the DWEYS peptide, a mimetope of dsDNA [33, 34]. The expression of RAG is dependent on the presence of soluble (self) antigen and IL-7R signaling, because removing endogenous DNA with DNase or treatment with IL-7R blocking antibody abrogated the induction of RAG. Importantly, ongoing Ig light chain editing was observed in this post-GC autoreactive population. When RAG expression was inhibited, the mice developed markedly higher titers of anti-DNA antibody, suggesting that receptor revision functions to restrain autoreactivity generated during an ongoing immune response. In this study, we showed that in Bcl-2 Tg mice, RAG expression was inhibited in the autoreactive early memory B cell population generated in response to DWEYS peptide immunization. We also demonstrated that overexpression of Bcl-2 decreases the stringency of tolerance maintenance in the post-activation B cell compartment, as Bcl-2 Tg mice developed a stronger anti-dsDNA memory response compared to WT mice. In order to decipher the possible mechanism for the absence of RAG induction, we first measured the abundance of DNA and apoptosis in Bcl-2 mice. As an apoptotic inhibitor, Bcl-2, when overexpressed, was shown to inhibit cell death and DNA release from cultured cells [39, 49] as well as B cells at various developmental stages, including the GC stage [40]. Consistent with these reports, we observed reduced levels of circulating DNA and apoptotic bodies in the spleen of Bcl-2 Tg mice immunized with DWEYS peptide. Next we tested whether B cells of Bcl-2 Tg mice were competent to receptor edit at the post-GC stage. Bcl-2 Tg mice were immunized with 10-2-KLH and then administered 10-2-BSA or BSA alone at the peak of the GC response. We observed that RAG was induced in antigen-reactive B cells by soluble 10-2-BSA and not by BSA alone. These data suggest that lack of sufficient (self) antigen, is responsible for the failure to induce RAG in DWEYS-immunized Bcl-2 Tg mice. These data are consistent with the study described above that demonstrated that the sle1 locus both permits the differentiation of GC-matured DNA-reactive B cells into memory cells and enables the overexpression of Bcl-2.

However, given the difference between self antigen (DNA) and exogenous peptide (10-2), including their structure and the avidity for BCR binding, we cannot exclude the possibility that in the autoimmunity setting the Bcl-2 transgene may perturb RAG expression through other mechanisms also. For example, Bcl-2 may modulate RAG expression through altering BCR signaling. We and others have observed an elevated BCR signaling in Bcl-2 overexpressing B cells, evidenced by enhanced calcium mobilization and phosphorylation of key mediators downstream the BCR pathway, such as PLCγ2 and ERK1/2 (data not shown), in response to anti-Igμ engagement. In immature B cells, it was reported that basal or innocuous BCR signaling maintains high PI3K activity that suppresses RAG transcription [50]. The inhibition of RAG expression by PI3K is mediated through PLCγ2[50]. Ligation of BCR on immature B cells diminished PLCγ2 activation and promoted sustained RAG expression and receptor editing. Moreover, in editing competent bone marrow B cells, transcription of RAG is positively controlled by the transcription factor NFκB/Rel protein [51]. Interestingly, Bcl-2 was shown to downregulate the activity of NFκB by suppressing the transactivating potential of p65/RelA in the nucleus [52]. At a more mature stage, RAG can also be induced by BCR signaling. Using the 3-83μδ Tg mice, Hertz et al reported that RAG and receptor editing were induced in splenic B cells by immunization with antigen of intermediate affinity, but not with non-binding or high-affinity antigen [53], suggesting an optimal BCR stimulation might be required for RAG expression in mature B cells. Therefore, it is possible that in the DNA-reactive early memory B cells overexpression of Bcl-2 altered the BCR signaling potential that is otherwise optimal for inducing RAG by DNA engagement. Finally, it is interesting to speculate that inhibition of RAG may also be related to the ability of Bcl-2 to limit cell cycle entry [54], since successful editing requires cell cycle progression beyond G1 phase. In fact, the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-2 can be separated from its inhibitory effect on cell cycle entry [55]. It would be informative to address whether overexpressing a Bcl-2 molecule that retains only the cell-cycle inhibitory function would still suppress RAG expression in antigen-activated B cells.

In summary, we have recently identified a tolerance checkpoint in antigen-activated early memory or pre-plasma B cells where receptor editing acts as a mechanism for tolerance induction. We show in this study that overexpression of Bcl-2 inhibits RAG expression and receptor editing in post-activation B cells and leads to an enhanced anti-DNA memory response in the peptide-induced model of autoimmunity. These data reveal a novel function of Bcl-2 in the regulation of B cell physiology and further extend our understanding of tolerance mechanisms following antigen activation in the peripheral immune system.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank S. Jones for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported by B. Diamond NIH grants; AI056362 and AR049126.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fuentes-Panana EM, Bannish G, Monroe JG. Basal B-cell receptor signaling in B lymphocytes: mechanisms of regulation and role in positive selection, differentiation, and peripheral survival. Immunol Rev. 2004;197:26–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajewsky K. Clonal selection and learning in the antibody system. Nature. 1996;381:751–8. doi: 10.1038/381751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klinman NR. The “clonal selection hypothesis” and current concepts of B cell tolerance. Immunity. 1996;5:189–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nossal GJ. Cellular mechanisms of immunologic tolerance. Annu Rev Immunol. 1983;1:33–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melamed D, Benschop RJ, Cambier JC, Nemazee D. Developmental regulation of B lymphocyte immune tolerance compartmentalizes clonal selection from receptor selection. Cell. 1998;92:173–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakhshi A, Jensen JP, Goldman P, Wright JJ, McBride OW, Epstein AL, Korsmeyer SJ. Cloning the chromosomal breakpoint of t(14;18) human lymphomas: clustering around JH on chromosome 14 and near a transcriptional unit on 18. Cell. 1985;41:899–906. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleary ML, Sklar J. Nucleotide sequence of a t(14;18) chromosomal breakpoint in follicular lymphoma and demonstration of a breakpoint-cluster region near a transcriptionally active locus on chromosome 18. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:7439–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.21.7439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsujimoto Y, Gorham J, Cossman J, Jaffe E, Croce CM. The t(14;18) chromosome translocations involved in B-cell neoplasms result from mistakes in VDJ joining. Science. 1985;229:1390–3. doi: 10.1126/science.3929382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandik L, Katsumata M, Erikson J. Effects of altered Bcl-2 expression on B lymphocyte selection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;815:40–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hande S, Notidis E, Manser T. Bcl-2 obstructs negative selection of autoreactive, hypermutated antibody V regions during memory B cell development. Immunity. 1998;8:189–98. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Notidis E, Hande S, Manser T. Enforced expression of Bcl-2 selectively perturbs negative selection of dual reactive antibodies. Dev Immunol. 2001;8:223–34. doi: 10.1155/2001/83595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuo P, Bynoe MS, Wang C, Diamond B. Bcl-2 leads to expression of anti-DNA B cells but no nephritis: a model for a clinical subset. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3168–78. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3168::AID-IMMU3168>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nisitani S, Tsubata T, Murakami M, Okamoto M, Honjo T. The bcl-2 gene product inhibits clonal deletion of self-reactive B lymphocytes in the periphery but not in the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1247–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strasser A, Whittingham S, Vaux DL, Bath ML, Adams JM, Cory S, Harris AW. Enforced BCL2 expression in B-lymphoid cells prolongs antibody responses and elicits autoimmune disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:8661–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marquina R, Diez MA, Lopez-Hoyos M, Buelta L, Kuroki A, Kikuchi S, Villegas J, Pihlgren M, Siegrist CA, Arias M, et al. Inhibition of B cell death causes the development of an IgA nephropathy in (New Zealand white x C57BL/6) F(1)-bcl-2 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2004;172:7177–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandik-Nayak L, Nayak S, Sokol C, Eaton-Bassiri A, Madaio MP, Caton AJ, Erikson J. The origin of anti-nuclear antibodies in bcl-2 transgenic mice. Int Immunol. 2000;12:353–64. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouillet P, Metcalf D, Huang DC, Tarlinton DM, Kay TW, Kontgen F, Adams JM, Strasser A. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 relative Bim required for certain apoptotic responses, leukocyte homeostasis, and to preclude autoimmunity. Science. 1999;286:1735–8. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nemazee D. Receptor selection in B and T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:19–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radic MZ, Zouali M. Receptor editing, immune diversification, and self-tolerance. Immunity. 1996;5:505–11. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radic MZ, Erikson J, Litwin S, Weigert M. B lymphocytes may escape tolerance by revising their antigen receptors. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1165–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiegs SL, Russell DM, Nemazee D. Receptor editing in self-reactive bone marrow B cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1009–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gay D, Saunders T, Camper S, Weigert M. Receptor editing: an approach by autoreactive B cells to escape tolerance. J Exp Med. 1993;177:999–1008. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halverson R, Torres RM, Pelanda R. Receptor editing is the main mechanism of B cell tolerance toward membrane antigens. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:645–50. doi: 10.1038/ni1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casellas R, Shih TA, Kleinewietfeld M, Rakonjac J, Nemazee D, Rajewsky K, Nussenzweig MC. Contribution of receptor editing to the antibody repertoire. Science. 2001;291:1541–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1056600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Retter MW, Nemazee D. Receptor editing occurs frequently during normal B cell development. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1231–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray SK, Putterman C, Diamond B. Pathogenic autoantibodies are routinely generated during the response to foreign antigen: a paradigm for autoimmune disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:2019–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han S, Zheng B, Schatz DG, Spanopoulou E, Kelsoe G. Neoteny in lymphocytes: Rag1 and Rag2 expression in germinal center B cells. Science. 1996;274:2094–7. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han S, Dillon SR, Zheng B, Shimoda M, Schlissel MS, Kelsoe G. V(D)J recombinase activity in a subset of germinal center B lymphocytes. Science. 1997;278:301–5. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hikida M, Mori M, Takai T, Tomochika K, Hamatani K, Ohmori H. Reexpression of RAG-1 and RAG-2 genes in activated mature mouse B cells. Science. 1996;274:2092–4. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papavasiliou F, Casellas R, Suh H, Qin XF, Besmer E, Pelanda R, Nemazee D, Rajewsky K, Nussenzweig MC. V(D)J recombination in mature B cells: a mechanism for altering antibody responses. Science. 1997;278:298–301. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang JH, Gostissa M, Yan CT, Goff P, Hickernell T, Hansen E, Difilippantonio S, Wesemann DR, Zarrin AA, Rajewsky K, et al. Mechanisms promoting translocations in editing and switching peripheral B cells. Nature. 2009;460:231–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang JH, Alt FW, Gostissa M, Datta A, Murphy M, Alimzhanov MB, Coakley KM, Rajewsky K, Manis JP, Yan CT. Oncogenic transformation in the absence of Xrcc4 targets peripheral B cells that have undergone editing and switching. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:3079–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rice JS, Newman J, Wang C, Michael DJ, Diamond B. Receptor editing in peripheral B cell tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1608–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409217102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang YH, Diamond B. B cell receptor revision diminishes the autoreactive B cell response after antigen activation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2896–907. doi: 10.1172/JCI35618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang J, Arnold B, Hammerling G, Harris AW, Korsmeyer S, Russell D, Strasser A, Nemazee D. Enforced Bcl-2 expression inhibits antigen-mediated clonal elimination of peripheral B cells in an antigen dose-dependent manner and promotes receptor editing in autoreactive, immature B cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1513–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. A B cell-deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exon of the immunoglobulin mu chain gene. Nature. 1991;350:423–6. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman J, Rice JS, Wang C, Harris SL, Diamond B. Identification of an antigen-specific B cell population. J Immunol Methods. 2003;272:177–87. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Putterman C, Diamond B. Immunization with a peptide surrogate for double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) induces autoantibody production and renal immunoglobulin deposition. J Exp Med. 1998;188:29–38. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fussenegger M, Fassnacht D, Schwartz R, Zanghi JA, Graf M, Bailey JE, Portner R. Regulated overexpression of the survival factor bcl-2 in CHO cells increases viable cell density in batch culture and decreases DNA release in extended fixed-bed cultivation. Cytotechnology. 2000;32:45–61. doi: 10.1023/A:1008168522385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith KG, Light A, O'Reilly LA, Ang SM, Strasser A, Tarlinton D. bcl-2 transgene expression inhibits apoptosis in the germinal center and reveals differences in the selection of memory B cells and bone marrow antibody-forming cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:475–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li YS, Hayakawa K, Hardy RR. The regulated expression of B lineage associated genes during B cell differentiation in bone marrow and fetal liver. J Exp Med. 1993;178:951–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merino R, Ding L, Veis DJ, Korsmeyer SJ, Nunez G. Developmental regulation of the Bcl-2 protein and susceptibility to cell death in B lymphocytes. Embo J. 1994;13:683–91. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nunez G, Hockenbery D, McDonnell TJ, Sorensen CM, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 maintains B cell memory. Nature. 1991;353:71–3. doi: 10.1038/353071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi Y, Cerasoli DM, Dal Porto JM, Shimoda M, Freund R, Fang W, Telander DG, Malvey E-N, Mueller DL, Behrens TW, et al. Relaxed Negative Selection in Germinal Centers and Impaired Affinity Maturation in bcl-xL Transgenic Mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:399–410. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuo P, Bynoe M, Diamond B. Crossreactive B cells are present during a primary but not secondary response in BALB/c mice expressing a bcl-2 transgene. Mol Immunol. 1999;36:471–9. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vuyyuru R, Mohan C, Manser T, Rahman ZS. The lupus susceptibility locus Sle1 breaches peripheral B cell tolerance at the antibody-forming cell and germinal center checkpoints. J Immunol. 2009;183:5716–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuo P, Alban A, Gebhard D, Diamond B. Overexpression of bcl-2 alters usage of mutational hot spots in germinal center B cells. Mol Immunol. 1997;34:1011–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(97)00117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bynoe MS, Grimaldi CM, Diamond B. Estrogen up-regulates Bcl-2 and blocks tolerance induction of naive B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2703–2708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040577497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tey BT, Singh RP, Piredda L, Piacentini M, Al-Rubeai M. Influence of bcl-2 on cell death during the cultivation of a Chinese hamster ovary cell line expressing a chimeric antibody. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2000;68:31–43. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(20000405)68:1<31::aid-bit4>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verkoczy L, Duong B, Skog P, Ait-Azzouzene D, Puri K, Vela JL, Nemazee D. Basal B cell receptor-directed phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling turns off RAGs and promotes B cell-positive selection. J Immunol. 2007;178:6332–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verkoczy L, Ait-Azzouzene D, Skog P, Martensson A, Lang J, Duong B, Nemazee D. A role for nuclear factor kappa B/rel transcription factors in the regulation of the recombinase activator genes. Immunity. 2005;22:519–31. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grimm S, Bauer MK, Baeuerle PA, Schulze-Osthoff K. Bcl-2 down-regulates the activity of transcription factor NF-kappaB induced upon apoptosis. The Journal of cell biology. 1996;134:13–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hertz M, Kouskoff V, Nakamura T, Nemazee D. V(D)J recombinase induction in splenic B lymphocytes is inhibited by antigen-receptor signalling. Nature. 1998;394:292–5. doi: 10.1038/28419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Reilly LA, Huang DC, Strasser A. The cell death inhibitor Bcl-2 and its homologues influence control of cell cycle entry. Embo J. 1996;15:6979–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang DC, O'Reilly LA, Strasser A, Cory S. The anti-apoptosis function of Bcl-2 can be genetically separated from its inhibitory effect on cell cycle entry. Embo J. 1997;16:4628–38. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]