Abstract

Gene expression profiling using DNA arrays is rapidly becoming an essential tool for research and drug discovery and may soon play a central role in disease diagnosis. Although it is possible to make significant discoveries on the basis of a relatively small number of expression profiles, the full potential of this technology is best realized through more extensive collections of expression measurements. The generation of large numbers of expression profiles can be a time-consuming and labor-intensive process with current one-at-a-time technology. We have developed the ability to obtain expression profiles in a highly parallel yet straightforward format using glass wafers that contain 49 individual high-density oligonucleotide arrays. This arrays of arrays concept is generalizable and can be adapted readily to other types of arrays, including spotted cDNA microarrays. It is also scalable for use with hundreds and even thousands of smaller arrays on a single piece of glass. Using the arrays of arrays approach and parallel preparation of hybridization samples in 96-well plates, we were able to determine the patterns of gene expression in 27 ovarian carcinomas and 4 normal ovarian tissue samples, along with a number of control samples, in a single experiment. This new approach significantly increases the ease, efficiency, and throughput of microarray-based experiments and makes possible new applications of expression profiling that are currently impractical.

Monitoring expression levels for thousands of genes at a time provides insights into cellular processes and responses that cannot be obtained by looking at one or a few genes. Traditional methods for gene expression measurements such as Northern blots can be time-consuming and labor-intensive and are not practical for application on a very large scale. The more global view and increased throughput made possible by the advent of parallel expression measurements with DNA microarrays has therefore opened a new window on cellular activity. As such, DNA arrays and global expression measurements provide one of the keys to deriving functional information from raw genome sequence (Hill et al. 2000; Shoemaker et al. 2001).

In many cases, however, a small number of experiments that cover thousands of genes is not sufficient. It has become increasingly clear that large collections of expression results are much more than the sum of their parts. The value of any single gene-expression profile is dependent on having other, related expression profiles for comparison. The analysis of multidimensional expression patterns can reveal new insights that may not be apparent when looking at the results from small numbers of samples (Hughes et al. 2000; Lockhart and Winzeler 2000; Ross et al. 2000; Scherf et al. 2000). The capacity to collect more profiles in parallel directly influences the ability to extract useful information and biological understanding, especially in the case of important studies that use human tissue (Golub et al. 1999; Alizadeh et al. 2000) or require timecourse or dose-response data.

Currently, both oligonucleotide and spotted cDNA arrays are hybridized and read one at a time and significant time and effort is required to process even a modest number of samples. However, to fully exploit the promise of DNA array technology requires the ability to rapidly generate very large collections of samples and high-quality expression profiles. Therefore, there is a great need for new approaches that are more parallel, efficient, and cost effective, while maintaining a high level of data quality.

To increase the throughput of DNA array-based experiments, we have developed methods to hybridize many samples in parallel to multiple arrays residing on a single glass slide or wafer (arrays of arrays). We have also modified the standard sample preparation protocols to allow production of hybridization samples directly from total RNA in a 96-well plate format. The combination of these methods allowed us to complete an entire study of gene expression profiles in ovarian cancer (Welsh et al. 2001) in a single experiment in a fraction of the time and with a fraction of the effort than would have been required with the conventional approach. The increased ease and throughput of our more parallel methods will enable applications of gene-expression profiling and other array-based measurements that are currently prohibitive due to intrinsic limitations of the serial one-array-at-a-time approach.

RESULTS

Expression profiles are typically obtained one at a time by hybridizing a single sample to a single array on an individual glass slide. Conceptually, this is the same as performing separate reactions in individual tubes. To allow parallel interrogation of multiple samples at once, we have developed an integrated device that can accommodate a 12.5-cm × 12.5-cm glass wafer that includes 49 individual oligonucleotide arrays arranged as a 7 × 7 array of arrays. This whole wafer approach is the DNA array equivalent of performing many reactions in parallel in multi-well (i.e., 96- or 384-well) plates.

For the experiments described here, we used Affymetrix HuGeneFL arrays. These high-density arrays contain sets of 25-mer oligonucleotide probes for detecting >6000 human genes, and are commercially available as individual chips. In the standard high-density oligonucleotide array manufacturing process, 49 of these arrays are synthesized on a single glass wafer. Usually these wafers are cut into 49 individual arrays that are then inserted into self-contained small plastic flow cells. We reasoned that all 49 arrays could be processed simultaneously with different samples if the wafer remained intact and if we had a way to separate the samples from each other during the hybridization step. We want to stress that although we have used Affymetrix oligonucleotide arrays, the approach can be readily adapted to other types of arrays. For example, most commercially available arrayers print cDNA microarrays on many 1 × 3-inch microscope slides laid out side by side on a work surface during each run. Minor modifications would allow a single uncut wafer to take the place of all of the individual slides, creating spotted cDNA arrays of arrays. The entire collection of microarrays could then be handled together as we describe here.

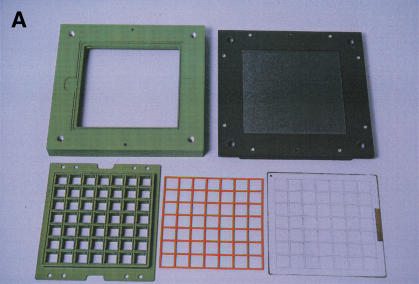

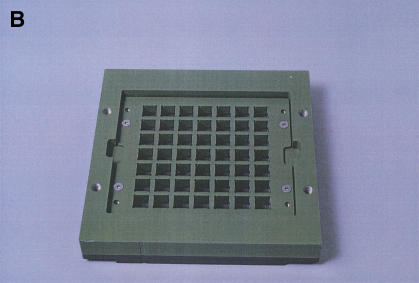

Our device serves as the hybridization chamber for 49 different samples and arrays as well as a whole-wafer flow cell during subsequent washing, staining, and scanning steps (Fig.1). The core of our design consists of a two-piece frame holding the wafer in place. Different modules can be attached on either side of the wafer at different processing stages. During hybridization, the arrays and samples are kept separated from each other by a silicone seal held in place and pressed against the wafer by a coated aluminum grid plate (Fig. 1A,B). A solid aluminum plate attached to the frame provides support from the back to prevent breaking of the thin glass wafer. Hybridization samples are applied to the arrays from above through the open grid (Fig. 1B). A sample volume of 300 μL is sufficient to completely cover each array. Evaporation is prevented by a solid lid pressing a second seal onto the grid plate (not shown). Following hybridization, the samples are recovered for reuse, and wash buffer is added onto the arrays to prevent them from drying out before the subsequent washing steps.

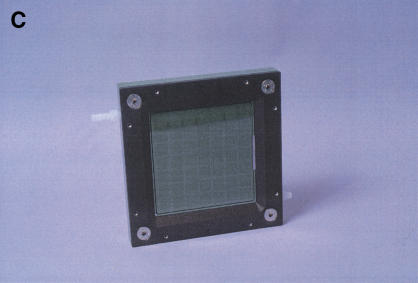

Figure 1.

The hybridization chamber/flow cell. (A) Components of the hybridization chamber. The glass wafer is shown in the front right, with individual arrays visible as squares. The size of the wafer is 12.5 cm × 12.5 cm. The grid plate and seal, which provide separation between the arrays during hybridizations, are in the front left and middle, respectively. The seal fits into a groove machined into the grid plate. The central frame is in the back left and the outer frame to which the support plate has already been attached is in the back right. (B) Assembled hybridization chamber. The central frame is shown from the direction facing downward in A. The wafer is clamped between the central and outer frames against an O-ring sitting in a groove on the central frame. The grid plate with the seal is attached to the central frame, pressing the seal against the wafer. (C) Flow cell. The grid plate and seal have been replaced by a solid plate with an O-ring around its periphery to prevent leakage and the back support plate has been removed. Teflon adapters attached to the ports in the central frame can be seen in white at the top, left and bottom right corners of the flow cell.

To convert the hybridization chamber into a flow cell for washing and staining of all of the arrays in parallel, the grid plate is removed and a solid, coated aluminum plate, held at a distance of 1.5 mm from the wafer, is attached in its place. This creates a space between the surface of the wafer and the solid plate that can be filled and vented through two ports in the frame (Fig.1C). Separation of individual arrays is not required for the steps following hybridization and removal of the samples. Removing the back support plate (see above) allows viewing of the wafer and completes the conversion into a single large flow cell containing all of the individual arrays with a total volume of ∼35 mL (Fig. 1C). Two sets of washes of increasing stringency are performed after the hybridization to remove sample RNA nonspecifically bound to the arrays. As in the standard procedure for oligonucleotide arrays (Affymetrix), the entire wafer is then stained with streptavidin-conjugated phycoerythrin, followed by further signal amplification with biotinylated anti-streptavidin and a second staining with streptavidin-conjugated phycoerythrin (see Methods).

After staining, the flow cell is attached to a translation stage and the arrays on the wafer are scanned with a confocal laser scanner at a spatial resolution of 3.4 mm/pixel. The scanner used is essentially identical to one described previously in detail (Chee et al. 1996; Stern 1999). Fluorescence emission is detected through a 555–607-nm bandpass filter. Each array on the wafer is scanned automatically in succession, and a separate file is produced for each array that can be analyzed with commercially available software (see Methods).

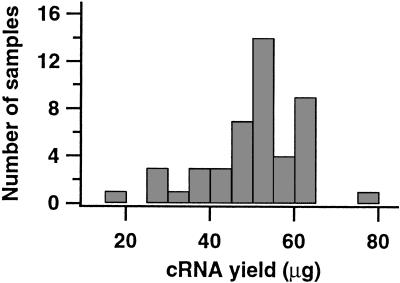

To test the whole wafer hybridization device, we measured gene-expression patterns in a panel of ovarian carcinomas (Welsh et al. 2001). Total RNA was isolated from 27 ovarian serous papillary adenocarcinomas, 4 normal ovarian tissue samples, 3 malignant ovarian epithelial cell lines, normal prostate stromal cells, and a mixture of fibroblasts. To efficiently produce biotin-labeled complementary RNA (cRNA) from each of these samples, as well as from five additional RNAs derived from a variety of cell lines and human tissues, we modified a previously described cRNA synthesis protocol (Lockhart et al. 1996; Wodicka et al. 1997; Mahadevappa and Warrington 1999) for use in a 96-well format (see Methods). The modified 96-well protocol significantly reduces the time and effort required to produce large numbers of samples and complements the parallel wafer-based hybridization approach. Starting with 5–7 μg of total RNA from each of 46 samples, including 5 prepared in duplicate, we obtained 15–76 μg of amplified, labeled cRNA (Fig. 2). In separate experiments, we have shown that cRNA prepared with the 96-well protocol produces expression profiles indistinguishable from those obtained with cRNA prepared individually (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Yields of 46 cRNAs synthesized in a 96-well format. Starting with 5–7 μg of total RNA, the mean yield was 50 μg of labeled cRNA, with a S.D. of 12 μg, a high of 76 μg, and a low of 15 μg. Only 15 μg of labeled material is used for each hybridization.

All 41 different biotin-labeled cRNAs were hybridized simultaneously to oligonucleotide arrays on a single wafer. cRNAs from two of the ovarian tumors and two ovarian cancer cell lines were each hybridized in duplicate, and a pool of cRNAs derived from several breast and prostate cancer cell lines (cRNA Mix) was hybridized to the remaining four arrays on the wafer. For 47 of the 49 arrays on the wafer, the images were of high quality and visually indistinguishable from images obtained by use of individual arrays. The only exceptions were two arrays that showed large bright spots, most likely due to contaminants introduced while the wafer was exposed to air during the conversion from hybridization chamber to flow cell (see above). The two arrays with bright spots were excluded from all subsequent analyses. The technical aspects of the whole wafer hybridizations are discussed here; a detailed analysis of gene expression in ovarian cancer is presented elsewhere (Welsh et al. 2001).

To assess the performance of the wafer in more detail, we hybridized two of the cRNA Mix samples as well as two samples from an ovarian cancer cell line (CAOV-3) to individual chips identical in design to those present on the wafer. By our standard measures of quality, including the fraction of genes queried that scored as present, the average signal intensity across the entire array and the background fluorescence levels, the results obtained from the wafer and the individual chips were very similar (Table 1). There was no significant decrease in sensitivity or hybridization specificity on the wafer and no increase in the frequency of defects or fluorescent blotches compared with individual chips.

Table 1.

Hybridization Quality

| Wafera | Indiv. chipsa | |

|---|---|---|

| % Presentb | 33 ± 3 | 37 ± 1 |

| Avg. signal intensitycd | 38 ± 8 | 30 ± 3 |

| Backgroundc | 38 ± 7 | 24 ± 3 |

Numbers are the mean ± standard deviation for 47 arrays on the wafer or four individual chips.

The percentage of genes queried on the arrays scored as present.

Arbitrary fluorescence units.

Average signal intensity for all genes queried on the arrays (see Methods).

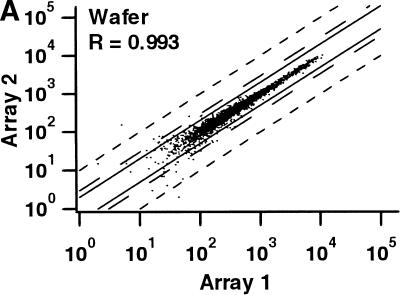

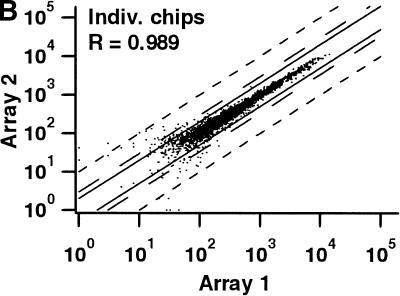

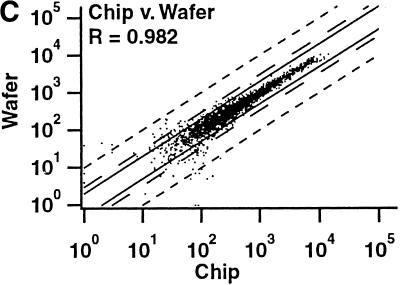

Two independent measures were used to compare the reproducibility of hybridizations with wafers and individual chips (Table 2). First, we calculated the pairwise correlation coefficients for the signal intensities of all genes scored as present in at least one of the two hybridizations being compared for both the wafer and individual chips (i.e., genes scored as absent in both hybridizations were excluded). Correlation coefficients for duplicate hybridizations of identical samples on both the wafer and the individual chips were >0.989 in all cases. The correlation coefficients were only slightly lower for comparisons between the results of wafer hybridizations and individual chip measurements (Table 2; Fig. 3). Second, we determined the number of probe sets that passed our standard criteria for calling a gene differentially expressed (Table 2). Fewer than 0.25% of all genes queried by the arrays passed the criteria for replicate hybridizations on the wafer or on individual chips, and fewer than 0.5% of all genes when comparing the wafer with chips. The false-positive rate for detection of differentially expressed genes on the wafer is therefore at least as low as when using individual chips.

Table 2.

Reproducibilitya

| Correlation coefficient | False positivesb | |

|---|---|---|

| Wafer | ||

| cRNA Mixc | 0.993 | 0 |

| CAOV-3d | 0.995 | 10 |

| Individual chips | ||

| cRNA Mix | 0.989 | 5 |

| CAOV-3 | 0.994 | 16 |

| Wafer vs. Indiv. chips | ||

| cRNA Mix | 0.982 | 19 |

| CAOV-3 | 0.980 | 31 |

Each row corresponds to a comparison of identical samples hybridized to two separate arrays.

The number of genes scored as present on at least one of the two arrays and differentially expressed (called as ‘increased’, ‘maybe increased’, ‘decreased’, ‘maybe decreased’ by the GeneChip software) by at least 1.8-fold with a change in signal intensity of at least 50 fluorescence units (a signal of 200 generally corresponds to ∼3–5 copies per mammalian cell [Lockhart and Winzeler 2000]). The total number of genes queried by the chips is ∼6800. The false positives shown here are for single comparisons. Because false positives are largely random, their numbers can be greatly minimized even further by performing replicate comparisons, as shown previously (Lockhart and Winzeler 2000; Sandberg et al. 2000).

A pool of RNA from MCF-7 and T47D breast cancer cells and LnCap prostate cancer cells.

CAOV-3 is a cell line derived from a malignant ovarian cancer.

Figure 3.

Comparison of signal intensities for individual genes from independent hybridizations of mixed breast and prostate cancer cell line RNA. For each comparison, only those genes scored as present on at least one of the two arrays are shown. The solid lines correspond to a twofold difference in signal intensity, the long broken lines to a threefold difference, and the short broken lines to a tenfold difference. (R) The correlation coefficient. (A) Identical samples hybridized to two different arrays on the same wafer. (B) The same samples hybridized to two separate, individual chips. (C) Comparison between array 1 in A and array 1 in B.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here show that it is possible to determine many gene-expression profiles in parallel by use of arrays of arrays on glass wafers, and that the expression patterns obtained in the more parallel format are of high quality. When combined with the 96-well sample preparation protocol also described here, this whole wafer hybridization approach greatly increases the rate at which gene-expression profiles can be generated and facilitates the construction of large collections of global gene-expression patterns. Both the sample preparation and whole wafer hybridization can be accomplished by one person in little more time and effort than is required to process a few individual samples and chips. Although not used here, additional time savings may be realized by use of commercially available kits for isolating total RNA from cells in a 96-well format (e.g., RNeasy 96 from Qiagen). The individual steps are readily automatable, and multiple plates and wafers can be processed in parallel. Even more important may be that, whereas we have used wafers with 7 × 7 individual arrays, wafers with larger numbers of smaller arrays can be used in a similar fashion to obtain hundreds of profiles in parallel. Such wafers, containing 169 arrays, are already produced by Affymetrix (Rat Neurobiology and Toxicology chips). Significant increases in the number of arrays per wafer can be accommodated in the device described here simply by modifying the grid plate and seal that separate the individual arrays during the hybridization (Fig. 1A,B). Furthermore, the concept of whole-wafer hybridizations is generalizable and could be applied to other array types; these include cDNAs spotted on glass or membranes (DeRisi et al. 1997; Alizadeh et al. 2000), arrays for SNP genotyping (Lindblad-Toh et al. 2000; Mei et al. 2000) or sequencing (Kozal et al. 1996; Hacia et al. 1998), exon and tiling arrays (Chee et al. 1996; Shoemaker et al. 2001), tag arrays (Winzeler et al. 1999), arrays of small molecules (MacBeath et al. 1999), and even protein arrays (MacBeath and Schreiber 2000).

The availability of a method for performing large numbers of DNA array-based experiments at once, in the form of arrays of arrays, significantly increases the power and utility of DNA arrays. For example, the application of parallel sample preparation and arrays of arrays opens the possibility of collecting large numbers of expression profiles for cells treated with chemical compounds that score as hits in conventional high throughput screens. Multi-gene expression profiles across multiple cell types have the potential to yield far more information about the activities of compounds and their effects on cells than is possible with conventional assays that test only single genes or pathways (Hughes et al. 2000; Scherf et al. 2000). The multi-gene, multi-sample information is expected to be of great value for deciding which compounds to focus on for continued development. Likewise, highly parallel methods make it feasible to use expression profiling as a diagnostic tool in a clinical setting. Although this has been mentioned repeatedly as an important application of the technology (Liotta and Petricoin 2000; Lockhart and Winzeler 2000; Young 2000), the time, effort , and cost required tend to be prohibitive using currently available technology. Finally, the use of DNA arrays as a tool to help annotate and interpret genome sequence information requires the construction of very large collections of expression profiles to generate comprehensive expression maps of many tissues, developmental stages, disease states, and cells under a multitude of conditions (Hill et al. 2000; Shoemaker et al. 2001). The increased speed and efficiency afforded by the application of the arrays of arrays concept is likely to greatly accelerate this process.

METHODS

cRNA Preparation in a 96-Well Format

Total RNA was isolated from tissue samples or cell lines by use of the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Double-stranded cDNA was produced by use of the Superscript Choice system (Life Technologies) as described before (Lockhart et al. 1996; Wodicka et al. 1997; Mahadevappa and Warrington 1999), except that only one-half of the volume recommended by the manufacturer was used in each step. Reactions were performed in a 0.2-mL 96-well plate in a thermocycler. cDNA was purified by use of the Qiaquick 96 PCR purification kit (Qiagen), transferred to a round-bottom 96-well plate, dried in a SpeedVac (Savant), and resuspended directly in T7 RNA polymerase transcription mix (Enzo Diagnostics). The 96-well plate was then placed in a 37°C water bath and transcription allowed to proceed for 4 h. cRNA was purified by use of the RNeasy 96 kit (Qiagen), transferred to a round-bottom 96-well plate, and concentrated in a SpeedVac. Yields were determined in a 96-well UV spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices).

Hardware

All metal parts for the hybridization chamber/flow cell were machined from aluminum. Those parts that contact sample or buffer were coated with green Teflon FEP (Crest Coating), and all other aluminum parts were hard anodized. Seals were custom molded to match the pattern of arrays on the wafer (Minnesota Rubber).

Hybridization, Washing, and Staining

For each hybridization sample, 15 μg of labeled cRNA were fragmented as described (Lockhart et al. 1996; Wodicka et al. 1997) and added to hybridization buffer (100 mM Tris at pH 7.0, 20 mM EDTA, 1 M NaCl, 0.01% Triton) that also contained 0.5 mg/mL acetylated bovine serum albumin (Life Technologies) and 0.1 mg/mL herring sperm DNA (Promega) in a 0.5-mL 96-well plate (Corning). The final volume for each sample was 300 μL. The plate containing the hybridization samples was heated to 94°C for 5 min in a water bath, incubated at 45°C for 5 min, and centrifuged at 5800g for 5 min before the samples were transferred to the wafer with a custom seven-channel expandable pipettor (Matrix Technologies). Hybridizations were performed at 45°C for 20 h without agitation or rotation. Samples were recovered, and the hybridization chamber converted to a flow cell (see main text). The wafer was washed 10 times with low-stringency wash buffer (0.9 M NaCl, 60 mM NaH2PO4 at pH 7.4, 6 mM EDTA, 0.01% Triton) and twice with high-stringency wash buffer (0.1 M Tris at pH 7.0, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.01% Triton), followed by a 30-min incubation at 45°C in high-stringency wash buffer. Wafers were stained for 15 min at 37°C with 0.01 mg/mL streptavidin–phycoerythrin (Molecular Probes) in staining buffer (0.1 M Tris at pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl, 0.05% Triton), washed 10 times with low stringency wash buffer, stained for 30 min at 37°C with 3 μg/mL biotinylated anti-streptavidin (Vector Laboratories) in staining buffer, washed 10 more times with low-stringency wash buffer, and stained a second time with streptavidin–phycoerythrin at 37°C for 15 min, followed by a final set of 10 low-stringency washes. Individual chips were hybridized, washed, and stained using the same protocol and buffers.

Scanning

Fluorescence images of hybridized, stained wafers were obtained by a custom-built confocal scanner (Stern 1999). An argon laser beam (488 nm, 3 mW) was galvanometer-scanned at 7.5 lines/sec (GSI Lumonics, model M2T galvanometer) and was focused to a 3-μm-diameter spot by a custom objective lens having a field of view of 14 mm and a numerical aperture of 0.25 (Special Optics, model 55-S30-15T). The wafer was mounted on a computer-controlled 3-axis translation stage (JMAR Precision Systems) with 150 mm of travel and 1 micron resolution. The wafer was translated slowly in one direction while the laser beam was galvanometer scanned in the orthogonal direction. Fluorescence from the wafer surface was separated from reflected laser light by a 505-nm longpass dichroic beamsplitter, filtered by a 555–607-nm bandpass filter, and detected by a photomultiplier. Photomultiplier output was digitized by a 12-bit data acquisition board (Measurement Computing Corp., model CIO-DAS16/330) installed in a computer. Wafers containing 49 chips were imaged automatically, one chip at a time. Each of the 49 images contains 4096 × 4096 pixels. Pixel size was 3.4 μm.

Data Analysis

Hybridization patterns were analyzed in the standard way by use of the GeneChip 3.2 software suite (Affymetrix). The software scores each gene as present or absent on the basis of the pattern of hybridization to a set of matched and mismatched probes. Quantitation of RNA abundance is based on a signal intensity for each gene that is derived from the average difference in fluorescence intensity between the matched and mismatched probes in each set (Lockhart et al. 1996; Wodicka et al. 1997). The number of genes meeting our criteria for false-positive changes in expression level (see Table 2) was determined by use of NFueggo software (Sandberg et al. 2000).

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Burger, Bradley Monk (University of California, Irvine, CA) and the Cooperative Human Tissue Network for generously providing tissue samples, Chris Harrington, Mark Trulson, and David Smith from Affymetrix for assistance, Lisa Wodicka, Helin Dong, and Guy Oshiro for many helpful discussions, Jeanne Geskes for help in the initial stages of developing the 96-well protocol, Todd Carter for testing hybridization patterns of cRNA prepared with the modified protocol, and Don Bambico for assistance with photography.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

Article published on-line before print: Genome Res., 10.1101/gr. 174801. Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.174801.

REFERENCES

- Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, Boldrick JC, Sabet H, Tran T, Yu X, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee M, Yang R, Hubbell E, Berno A, Huang XC, Stern D, Winkler J, Lockhart DJ, Morris MS, Fodor SPA. Accessing genetic information with high-density DNA arrays. Science. 1996;274:610–614. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRisi JL, Iyer VR, Brown PO. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science. 1997;278:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, Coller H, Loh ML, Downing JR, Caligiuri MA, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: Class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286:531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacia JG, Sun B, Hunt N, Edgemon K, Mosbrook D, Robbins C, Fodor SPA, Tagle DA, Collins FS. Strategies for mutational analysis of the large multiexon ATM gene using high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Genome Res. 1998;8:1245–1258. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.12.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AA, Hunter CP, Tsung BT, Tucker-Kellogg G, Brown EL. Genomic analysis of gene expression in C. elegans. Science. 2000;290:809–812. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TR, Marton MJ, Jones AR, Roberts CJ, Stoughton R, Armour CD, Bennett HA, Coffey E, Dai H, He YD, et al. Functional discovery via a compendium of expression profiles. Cell. 2000;102:109–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozal MJ, Shah N, Shen N, Yang R, Fucini R, Merigan TC, Richman DD, Morris D, Hubbell E, Chee M, et al. Extensive polymorphisms observed in HIV-1 clade B protease gene using high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Med. 1996;2:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblad-Toh K, Tanenbaum DM, Daly MJ, Winchester E, Lui W-O, Villapakkam A, Stanton SE, Larsson C, Hudson TJ, Johnson BE, et al. Loss-of-heterozygosity analysis of small-cell lung carcinomas using single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/79269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta L, Petricoin E. Molecular profiling of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:48–56. doi: 10.1038/35049567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart DJ, Winzeler EA. Genomics, gene expression and DNA arrays. Nature. 2000;405:827–836. doi: 10.1038/35015701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart DJ, Dong H, Byrne MC, Follettie MT, Gallo MV, Chee MS, Mittmann M, Wang C, Kobayashi M, Horton H, et al. Expression monitoring by hybridization to high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1675–1680. doi: 10.1038/nbt1296-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBeath G, Schreiber SL. Printing proteins as microarrays for high-throughput function determination. Science. 2000;289:1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBeath G, Koehler AN, Schreiber SL. Printing small molecules as microarrays and detecting protein-ligand interactions en masse. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7967–7968. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevappa M, Warrington JA. A high-density probe array sample preparation method using 10- to 100-fold fewer cells. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:1134–1136. doi: 10.1038/15124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei R, Galipeau PC, Prass C, Berno A, Ghandour G, Patil N, Wolff RK, Chee MS, Reid BJ, Lockhart DJ. Genome-wide detection of allelic imbalance using human SNPs and high-density DNA arrays. Genome Res. 2000;10:1126–1137. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.8.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross DT, Scherf U, Eisen MB, Perou CM, Rees C, Spellman P, Iyer V, Jeffrey SS, Van de Rijn M, Waltham M, et al. Systematic variation in gene expression patterns in human cancer cell lines. Nat Genet. 2000;24:227–235. doi: 10.1038/73432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg R, Yasuda R, Pankratz DG, Carter TA, Del Rio JA, Wodicka L, Mayford M, Lockhart DJ, Barlow C. Regional and strain-specific gene expression mapping in the adult mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:11038–11043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.11038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherf U, Ross DT, Waltham M, Smith LH, Lee JK, Tanabe L, Kohn KW, Reinhold WC, Myers TG, Andrews DT, et al. A gene expression database for the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Nat Genet. 2000;24:236–244. doi: 10.1038/73439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker DD, Schadt EE, Armour CD, He YD, Garrett-Engele P, McDonagh PD, Loerch PM, Leonardson A, Lum PY, Cavet G, et al. Experimental annotation of the human genome using microarray technology. Nature. 2001;409:922–927. doi: 10.1038/35057141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D. 1999. Systems and methods for detection of labeled materials. (Affymetrix, Inc., USA). US patent #5,981,956.

- Welsh JB, Zarrinkar PP, Sapinoso LM, Behling CA, Monk BJ, Lockhart DJ, Burger RA, Hampton GM. Highly parallel identification of molecular markers for epithelial ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:1176–1181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, Bangham R, Benito R, Boeke JD, Bussey H, et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodicka L, Dong H, Mittmann M, Ho M-H, Lockhart DJ. Genome-wide expression monitoring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:1359–1367. doi: 10.1038/nbt1297-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RA. Biomedical discovery with DNA arrays. Cell. 2000;102:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]