Abstract

African American men have the highest rates of prostate cancer of any racial group, but very little is known about the psychological functioning of African American men in response to prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Purpose

In this secondary analysis of a national trial testing a psychological intervention for prostate cancer patients, we report on the traumatic stress symptoms of African American and non-African American men.

Methods

A total of 329 men were enrolled in the intervention trial, which included 12 weeks of group psychotherapy and 24 months of follow-up. Using mixed model analysis, total score on the Impact of Events Scale (IES) and its Intrusion and Avoidance subscales were examined to determine mean differences in traumatic stress across all time points (0, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months). In an additional analysis, relevant psychosocial, demographic, and clinical variables were added to the model.

Results

Results showed significantly higher levels of traumatic stress for African American men compared to non-African American men in all models independently of the intervention arm, demographics and relevant clinical variables. African Americans also had a consistently higher prevalence of clinically significant traumatic stress symptoms (defined as IES total score ≥ 27). These elevations remained across all time points over 24 months.

Conclusions

This is the first study to show a racial disparity in traumatic stress specifically as an aspect of overall psychological adjustment to prostate cancer. Recommendations are made for appropriate assessment, referral, and treatment of psychological distress in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, African American, PTSD, traumatic stress, health disparities

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men, with 192,280 incident cases expected in 2009 [1]. African American men (along with Jamaican men of African descent) have the highest prostate cancer rates in the world. In 2007, 30,870 incident cases were expected in African Americans, and a marked disparity in the rate of prostate cancer was evident in African American men (258.3 per 100,000) compared to white men (163.4 per 100,000; rate ratio = 1.6) between 2000 to 2003 [2]. African American men were also more than twice as likely to die of prostate cancer (64.0 per 100,000 vs. 26.2 per 100,000; rate ratio = 2.4) during the same period [2].

Prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment is stressful for men and their families. The diagnosis coupled with treatment-related side effects impacting urinary, sexual, and bowel functioning can be expected to cause distress not only because of anxiety related to mortality, but also because of the assault on notions of masculinity [3]. Characterizing the psychological functioning of African American prostate cancer patients can lead to targeted interventions in this vulnerable group. Such intervention can be expected to improve psychological adjustment to cancer and may contribute to better coping with long-term physical sequelae, compliance with treatment and follow-up, and survival.

While several studies have described psychological distress in prostate cancer patients in general, very little is known about the psychological adjustment of African American men to prostate cancer. However, the poorer health-related quality of life that has been reported in the literature suggests that psychological functioning may be worse for African American men [4,5]. For example, Lubeck et al. found that in addition to poorer health status and physical functioning, black prostate cancer patients had poorer emotional functioning and self-esteem and more health-related distress than white men [5]. A limited body of research suggests that African American prostate cancer patients may be experiencing significantly worse health-related quality of life and take longer to return to their baseline functioning [6], which may include psychological functioning, but more research is needed to confirm these suggestions.

The significant stress of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment and the poorer physical and psychological functioning of African American men suggest that they might be at an increased risk for the development of a traumatic stress response to cancer. With the inclusion of life-threatening illness such as cancer as a stressor sufficient to cause posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)[7] a growing body of literature has documented traumatic stress in cancer patients [8,9]. According to the DSM-IV, traumatic stress responses are elicited in response to “direct personal experience of an event that involves actual or threatened death or serious injury”, and the reaction is one of intense fear, helplessness, or horror [7]. Symptoms of traumatic stress include a) intrusive thoughts about the stressor, b) avoidance of reminders of the traumatic events and emotional numbing, and c) physiologic hyperarousal and hypervigilance. Studies have reported a wide range for the incidence of PTSD and traumatic stress symptoms (0 to 32%) in cancer patients. However, these estimates have been based largely on women with breast cancer, and there is wide methodological variability in the assessment of symptoms [9]. Very few studies have examined traumatic stress responses in men with cancer, but in general, men have lower rates of PTSD in cancer and non-cancer populations [8,10]. A relatively small segment of the population develops PTSD following an exposure to a traumatic event, with rates varying from 3.6 to 13.8% (see recent literature review [11]), however Breslau [11] suggests that those who develop PTSD seem to be the most psychiatrically vulnerable individuals. They are either at high risk for the development of psychiatric illness such as depression and/or anxiety or have a history of early childhood adversity or personal and family psychiatric history. Identifying subgroups of cancer patients who are experiencing traumatic stress symptoms will allow us to target supportive psychiatric care. African American men with prostate cancer may be in need of these targeted treatment efforts.

We conducted this secondary analysis within the context of a larger trial testing the efficacy of a supportive-expressive group therapy intervention for men with prostate cancer [12]. In previous studies, supportive-expressive group therapy, which emphasizes the expression of emotion within a supportive group environment, was found to decrease psychological distress and traumatic stress symptoms in women with metastatic breast cancer [13]. The primary outcome of interest for the primary study was whether the intervention would result in better psychological adjustment compared to an educational information control as measured by the Profile of Mood States (POMS) total mood disturbance scale. Preliminary results were not supportive of an overall effect on mood disturbance. Because of the finding with regard to traumatic stress symptoms in the metastatic breast cancer study, we were especially interested in this aspect of psychological functioning and any evidence of racial differences. We hypothesized that African American men would experience significantly greater traumatic stress symptoms, including both intrusive thoughts and avoidant behaviors measured by the Impact of Events Scale (IES). We further hypothesized that African American men would have a higher prevalence of traumatic stress compared to non-African American men based upon the poorer adjustment to physical functioning and psychological adjustment reported in the literature [4, 5]. In addition, we predicted that these health disparities in traumatic symptoms would persist even after controlling for socioedemographic and clinical characteristics, distress, and illness interference, shown to be significant predictors of traumatic stress and PTSD in other studies [8, 9].

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Rochester and each participating site approved the protocol in accordance with an assurance filed with and approved by the Department of Health and Human Services. All participants provided informed written consent.

Participants

Participants were recruited from community clinical oncology practices throughout the United States under the NCI-funded University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program (URCC CCOP) and from two academic medical centers. All participants were referred by their physicians and then given information on the study by research coordinators at each site. The majority of African American participants were recruited from three CCOP affiliates: Southeast Cancer Control Consortium (based in Winston-Salem, North Carolina; n = 14, 45%), Wichita CCOP (Kansas; n = 6, 19%), and Kalamazoo CCOP (Michigan; n = 5, 16%). The six remaining African American participants were recruited from Greater Phoenix CCOP (Arizona; n = 2, 7%), University of Rochester Medical Center – Strong Memorial Hospital (New York; n = 2, 7%), Northwest CCOP (Washington; n = 1, 3%), and Stanford University Medical Center (n = 1; 3%).

Eligible participants had to be/have:

Men diagnosed with a first occurrence of biopsy-proven clinical stage T1b, T1c, or T2 NO or NX, MO prostate cancer.

Followed by a urologist, medical oncologist, or radiation therapist at least semi-annually.

No other cancers (except basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma of the skin) in the past 10 years.

No history of major psychiatric illness requiring hospitalization or medication (other than depression or anxiety for less than one year).

While 329 participants were enrolled in the study, 327 men provided evaluable data (2 were ineligible). Only men who provided racial background and completed the IES are included in this analysis (N = 317).

Procedures

Participants were randomized to receive either a supportive-expressive group therapy (intervention) or educational material (control). Randomization was stratified by CCOP site and by hormonal therapy status (Stratum 1: no permanent, long-term hormone therapy [bilateral orchiectomy]; Stratum 2: antiandrogen monotherapy [Flutamide or Casodex]; Stratum 3: standard hormone therapy [LH/RH agonists, estrogen/DES]). The educational material group received a series of booklets providing information on prostate cancer, cancer treatment, and coping with cancer. Each control group participant received the educational materials in the mail or in person at approximately the same time the intervention group began. They were instructed to read the material at their own pace. The supportive-expressive therapy group intervention consisted of 12 weekly 90-minute sessions led by two co-therapists trained in the treatment protocol. Groups were comprised of 8–12 members. Themes for the sessions included (in order of presentation): 1) Building Bonds, 2) Expressing Emotions, 3) Detoxifying Dying (i.e., reframing fears related to the process of dying), 4) Taking Time, 5) Fortifying Families, and 6) Dealing with Doctors. Each session began with a brief stress reduction exercise and ended with a brief cognitive restructuring (i.e., altering or reframing negative beliefs and attitudes) exercise. The main part of the sessions emphasized providing a supportive environment in which participants could share their concerns about the cancer experience with others in similar circumstances.

Both the intervention and control groups completed assessments by mailed paper-and-pencil questionnaires at baseline (prior to the first group therapy session) and at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. These questionnaires assessed sociodemographic and medical status, mood disturbance, social interaction, ability to cope with and adjust to having cancer, and health activities.

Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Participants completed a demographic questionnaire assessing age, marital status, race, education, employment, and family income. Information was also collected on each participant’s clinical status (e.g., stage).

Traumatic stress

The Impact of Events Scale (IES)[14] is a 15-item scale used to assess intrusive cognitions and avoidant thoughts and behaviors associated with a traumatic event. It has also been used extensively as a measure of traumatic psychological distress in cancer populations [15]. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 4 = often). The IES yields a total score along with two subscales: Intrusion and Avoidance. Higher total scores indicate greater traumatic stress. The IES has also been shown to be sensitive to the effects of psychotherapeutic treatment [14].

Mood disturbance

The Profile of Mood States (POMS)[16] is 65-item scale designed to measure affective states that has well established reliability and validity and has been extensively used in psychological intervention research in cancer [17]. Respondents are asked to rate a list of adjectives that describe different affective states (i.e., angry, tense, energetic, etc.) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely). Overall mood disturbance is represented by the total mood disturbance score, with higher scores representing greater mood disturbance. The POMS has been used in previous research on supportive-expressive group therapy in breast cancer patients [13, 18], and the POMS has been shown to be sensitive to changes associated with psychotherapeutic treatment.

Illness Intrusiveness

The Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale (IIRS)[19] is a 13-item scale that measures the extent to which illness and/or treatment interferes with activities of daily living. Respondents are asked to rate the extent of interference in various domains of daily life (e.g., diet, work, relationships, etc.) on an 8-point Likert scale (0 = not very much, 7 = very much). The IIRS has been used in previous research involving patients with chronic diseases [20] and has demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported for baseline demographic and disease characteristics for the two racial groups (African American vs. non-African American men). Means, standard deviations, and percentages are reported as appropriate. Chi-square tests were used to determine any significant differences in categorical or dichotomous data, and t-tests were used for continuous data. All hypothesis tests were two-tailed at the .05 level of significance.

A mixed modeling approach was used to evaluate the magnitude and statistical significance of mean IES Total and subscale score differences between African Americans and non-African Americans (AfrAmer) for each follow-up (Time), adjusting for effects of the supportive-expressive treatment (Trt), which was not found to be effective in significantly reducing distress in a separate set of primary preliminary analyses [12]. The fixed effects in the model were AfrAmer, Time, Trt and all second-order interactions. All these factors were treated as nominal data. Time, in particular, was treated as nominal rather than continuous to allow for potential nonlinearity in the mean follow-up profiles. The random effects were patient-to-patient mean and within-patient residual error. A random slope term (residual versus time) was included initially, but removed because it was very small relative to the patient-patient and within-patient variance components (p > 0.5). The restricted maximum likelihood (REML) procedure was used to make this assessment. The final model was fit using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. F-Tests using the Kenward-Roger [21] degrees of freedom adjustment were used to assess the significance of the fixed effects model terms. To account for levels of overall distress, the impact of illness on psychosocial functioning, and the demographic and clinical difference identified at baseline, effects of POMS-Total Mood Disturbance, IIRS-Total, income, and stage were investigated by adding these variables to the above model as main effects with the IES-Total as the dependent variable. Adjusted (least squares) means were calculated for African Americans and non-African Americans for each follow-up and across all follow-ups. SAS Version 9.2 Proc Mixed was used for the analyses.

Prevalence of clinically significant traumatic stress was determined by calculating the proportion of African Americans and non-African Americans at each follow-up who reported IES total scale scores ≥ 27, as suggested in the literature [22]. Chi-square tests were used to determine whether there were significant differences between these proportions at each time point.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents baseline demographic and clinical data for the sample with comparisons by race. Ten percent (10%) of the sample was African American (n = 30) and 90% (n = 286) was non-African American, including 281 who reported race as white, 3 Hispanic, and 2 Asian or Pacific Islander. The overall mean age was 66 years (SD = 8.3). There were significant racial differences (ps < .05) in household income and stage. Non-African American men were more likely to be in the highest ($40,000+; 56% vs. 23%) income group than African American men, who were more likely to be in the lowest (<$20,000; 17% vs. 8%) and middle ($20,000 to $39,000 40% vs. 24%) income groups. African American men were also more likely to be unsure of, or to refuse to disclose, their household income (20% vs. 12%). African American men were more likely to have Stage I (50% vs. 38%) or Stage III (7% vs. 1%) disease, and white men were more likely to have Stage II disease (61% vs. 43%).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Total | African American | Non-African American | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 329 | 31 (9%) | 298 (91%) | |

| Mean Age (sd); range 42–86 | 66 (8.4) | 65 (9.4) | 66 (8.4) | .297 |

| Educationa | ||||

| High school or less | 110 (35%) | 16 (53%) | 94 (33%) | .071 |

| College or some college | 119 (38%) | 7 (23%) | 112 (39%) | |

| Graduate or some graduate | 87 (28%) | 7 (23%) | 80 (28%) | |

| Household Incomea | ||||

| <$20,000 | 28 (9%) | 5 (17%) | 23 (8%) | .007 |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 80 (25%) | 12 (40%) | 68 (24%) | |

| $40,000+ | 168 (53%) | 7 (23%) | 161 (56%) | |

| Don’t know/Refuse | 40 (13%) | 6 (20%) | 34 (12%) | |

| Employment Statusa | ||||

| Not employed | 189 (60%) | 18 (60%) | 171 (60%) | .163 |

| Employed part-time | 34 (11%) | 6 (20%) | 28 (10%) | |

| Employed full-time | 93 (29%) | 6 (20%) | 87 (30%) | |

| Marital Statusa | ||||

| Married or living together | 266 (84%) | 22 (73%) | 244 (85%) | .087 |

| Not married | 50 (16%) | 8 (27%) | 42 (15%) | |

| Stage | ||||

| I | 127 (39%) | 15 (48%) | 112 (38%) | .048 |

| II | 196 (59%) | 14 (45%) | 182 (61%) | |

| III | 6 (2%) | 2 (7%) | 4 (1%) | |

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

n = 316 due to missing baseline data from refusers (n = 11), the ineligible (n = 1), and a patient who did not speak English (n = 1).

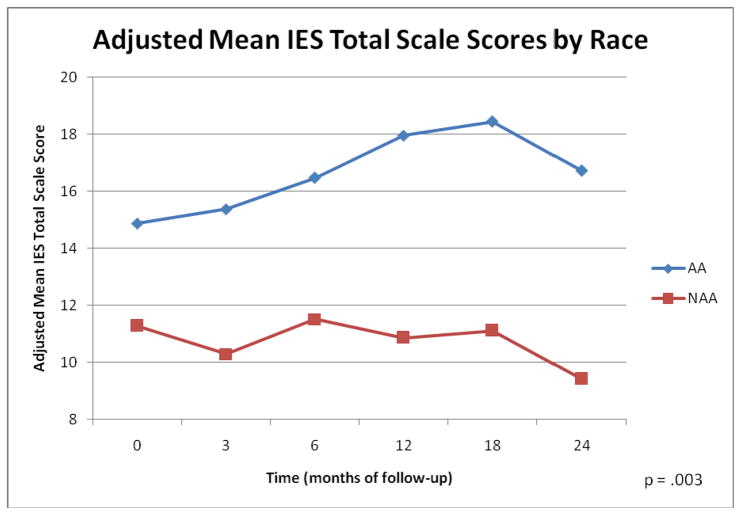

Table 2 presents the results for tests of fixed effects in each mixed model. The only significant term in the first model with the IES-Total as the dependent variable was the difference between African Americans and non-African Americans (AfrAmer) (p = .0006). For the models investigating the Intrusion and Avoidance subscales, the p-values for the AfrAmer term were .0022 and .0011, respectively. Again, this was the only significant term in each of these models. For all of these models the interaction of race by time was non-significant, meaning that the racial difference in IES total and subscale scores was relatively constant across follow-up times. In the model that additionally accounted for distress, impact of illness, and demographic (i.e., income) and clinical (i.e., stage) variables, the overall adjusted means (s.e.) for the IES-Total were 16.6 (2.1) for African Americans and 10.8 (1.3) for non-African Americans. Distress and impact of illness effects were statistically significant (ps < .001). The coefficient (s.e.) for POMS Total and IIRS were .14 (.02) and .08 (.02), respectively. These effects are substantial given the wide ranges for POMS (−40 to 140) and IIRS (0 to 85). Figure 1 graphically presents the adjusted (least square) means for the final model by race at each follow-up time point.

Table 2.

Fixed effects of mixed models

| F | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| IES-T (n = 317) | ||

| Time | 0.60 | .70 |

| AfrAmer | 11.96 | <.01 |

| AfrAmer*Time | 0.94 | .45 |

| Trt | 0.14 | .70 |

| Trt*Time | 1.50 | .19 |

| Trt*AfrAmer | 0.35 | .55 |

| Trt*Time*AfrAmer | 0.96 | .44 |

| IES-I (n = 317) | ||

| Time | 0.50 | .77 |

| AfrAmer | 9.50 | <.01 |

| AfrAmer*Time | 0.84 | .52 |

| Trt | 1.45 | .23 |

| Trt*Time | 0.57 | .72 |

| Trt*AfrAmer | 1.67 | .20 |

| Trt*Time*AfrAmer | 0.21 | .96 |

| IES-A (n = 317) | ||

| Time | 0.97 | .44 |

| AfrAmer | 10.83 | <.01 |

| AfrAmer*Time | 1.18 | .32 |

| Trt | 0.12 | .73 |

| Trt*Time | 2.14 | .06 |

| Trt*AfrAmer | 0.00 | .96 |

| Trt*Time*AfrAmer | 1.65 | .14 |

| IES-T (n = 275)a adjusted for POMS-TMD, IIRS, income, and stage | ||

| Time | 0.63 | .68 |

| AfrAmer | 8.86 | <.01 |

| AfrAmer*Time | 0.53 | .75 |

| Trt | 0.22 | .64 |

| Trt*Time | 1.02 | .41 |

| Trt*AfrAmer | 0.25 | .62 |

| Trt*Time*AfrAmer | 1.12 | .35 |

| POMS-TMD | 77.32 | <.01 |

| IIRS | 12.82 | <.01 |

| Income | 0.07 | .79 |

| Stage | 0.74 | .48 |

Note: IES-T = Impact of Events Total Scale; IES-I = Impact of Events Intrusion Subscale; IES-A = Impact of Events Avoidance Subscale

Sample size is reduced because of missing values for variables added to the model.

Figure 1.

Adjusted (Least Square) Means for Traumatic Stress (IES-T) by Race

Table 3 presents the prevalence of clinically significant traumatic stress symptoms (IES-T ≥ 27) by race at each follow-up time point. African Americans show a consistently higher prevalence of clinically significant traumatic stress compared to non-African Americans (26.1–40.9% vs. 12.2–14.3%), and the proportions were all statistically significant except (ps < .05) except at the 6-month time point (p = .12).

Table 3.

Prevalence of clinically significant traumatic stress symptoms by race (IES-T ≥ 27)

| Follow-Up | African American (%) | Non-African American (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 34.5 | 13.7 | <.01 |

| 3 mo. | 28.0 | 12.8 | .04 |

| 6 mo. | 26.1 | 14.1 | .12 |

| 12 mo. | 40.9 | 14.3 | <.01 |

| 18 mo. | 33.3 | 13.7 | .02 |

| 24 mo. | 39.1 | 12.2 | <.01 |

DISCUSSION

The objectives of this study were to characterize differences in the experience of traumatic stress for African American and non-African American men with prostate cancer enrolled in a study of supportive-expressive group psychotherapy. We are unaware of any previous study that has compared African American men to other men with prostate cancer in this important aspect of psychological functioning. As hypothesized, African American men reported significantly greater levels of traumatic stress, including both avoidant coping and intrusive thoughts, compared to non-African American men across all time points. Racial differences in traumatic stress remained significant across time, even after accounting for mood disturbance, impact of illness, income and disease stage. African American men also had a consistently higher prevalence of clinically significant traumatic stress symptoms with the exception of the 6-month follow-up. These findings are consistent with previous reports of poorer emotional functioning and greater health-related distress in African American men compared to whites [5]. They are also consistent with recent evidence that blacks in the United Stated are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to meet criteria for the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and are more impaired by the effects of mental illness [23]. However, this is the first study to show a racial disparity in traumatic stress specifically as an aspect of overall psychological adjustment to prostate cancer.

Several factors may explain the greater burden of traumatic stress for African American men with prostate cancer in this sample. African American men are at higher risk for many of the factors related to traumatic stress responses to cancer, including disproportionately low income, lower educational attainment, and history of other negative life stressors [8, 9]. The main effect of income was not significant in the final model, and because education was similar for African Americans and non-African Americans in this sample, this variable was not tested. Given the role of previous trauma in the risk of cancer-related traumatic stress, the higher prevalence of PTSD among blacks in the general population also may predispose African American men to traumatic stress responses to cancer. Despite lower rates for most anxiety disorders, the higher rate of PTSD among African Americans has been attributed to both race-related stressors (e.g., racial discrimination, prejudice, stigmatization) and higher exposure to environments in which traumatization is common (e.g., neighborhoods with high rates of crime and/or violence) [24]. Greater distress in response to the diagnosis of cancer has also been associated with traumatic stress [9, 25, 26]. The literature on cancer-related PTSD has been mixed in terms of the extent to which clinical characteristics are predictive of the disorder [9], but it is possible that greater difficulty adjusting to changes in physical functioning for African American men [5] may also contribute to their higher degree of traumatic stress. The significant main effect for mood disturbance and the impact of illness in this study is consistent with the role of distress and illness-related adjustment in the development of traumatic stress symptoms reported in the literature.

The prevalence of clinically significant traumatic stress among African Americans in this sample is also noteworthy. While overall estimates of the prevalence of PTSD following cancer range from 0 to 32% [9], the prevalence of clinically significant traumatic stress symptoms (as determined by a score of ≥ 27 on the Impact of Events total score) among African Americans in this sample was from 26 to 41% depending on the assessment point. This prevalence is much higher than the estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD for African Americans (9.10%), Caribbean blacks (8.42%), and non-Hispanic whites (6.84%) [23]. While the IES is not a diagnostic tool for PTSD, it has been shown to predict cases of PTSD [22], and it has been used extensively in the literature on traumatic stress in cancer patients and survivors [9]. Whether they could be diagnosed with clinical cases of PTSD or show only subsyndromal manifestations of the disorder, it appears evident that African American men with prostate cancer are experiencing significant traumatic stress in response to diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship.

Clearly, the higher levels of traumatic stress symptoms among African American prostate cancer survivors indicate that culturally appropriate, targeted interventions are needed in order to address the needs of African American cancer patients and cancer survivors [27]. The same principle holds for interventions involving men in general. It is already known that men with cancer are less likely to seek help from support groups than women and that those men who do participate are primarily interested in the information and education they receive regarding the disease [28–30]. To the extent that group interventions are desirable for their efficiency, their effectiveness with men may be enhanced by an emphasis on the provision of information and education rather than the expression of emotion, which can come later. When African American men are the targets of such intervention, the information should be specific to their experience and may potentially address the psychosocial stressors associated with race that likely compound the immediate stressor of cancer diagnosis and treatment. Culturally appropriate suggestions for coping (e.g., use of familiar community resources like churches, social and fraternal organizations for support) might also be incorporated along with the opportunity for individual psychotherapeutic intervention should individuals express interest. Such culturally appropriate, targeted interventions need to be tested for effectiveness in African American and other racial and ethnic minority male cancer populations. To date women have been the primary focus of interventions addressing psychological adjustment to cancer and quality of life. More interventions targeted at diverse populations of men with cancer are needed.

Several limitations should be noted. First, this was a secondary analysis of data collected for a psychological intervention trial. The original study was not designed to test the specific questions under investigation in this secondary analysis. Second, while African American recruitment was roughly in line proportionally with the representation of African Americans in the United States population, the relatively small sample size makes it difficult to generalize to all African American men with prostate cancer. While this study is not unique in having a small number of African American subjects, future studies including larger numbers of African American men are needed to confirm our findings. In addition, it is possible that African American men who were willing to participate in a group therapy intervention may differ in significant ways from other African American men with prostate cancer. For example, the former may have been in greater distress and therefore sought out this option to alleviate distress. This study was also limited by its inability to account for time since diagnosis as a relevant variable in analyses. Eligibility requirements of the parent study only stipulated that group therapy sessions had to begin within 24 months of the date of diagnosis of all group members. Data on the exact dates of diagnosis and subsequent treatment were not collected, and therefore, were not available for analyses. Despite these limitations, this study provides important information in an area of health disparities given relatively little attention in the literature, namely the psychological functioning of African American prostate cancer patients.

Our findings suggest that African American men may be experiencing significant traumatic stress symptoms in response to cancer diagnosis and treatment, and that these symptoms remain elevated for some time afterwards. In light of the disproportionate burden of prostate cancer carried by African American men and the increased survival of all men with prostate cancer, it is imperative that their psychological needs be assessed and that proper treatment be provided. Referrals for mental health intervention should be combined with the use of appropriate community resources in order to ensure culturally appropriate care for this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge financial support from the National Cancer Institute (CA037420 & R25CA102618).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2007–2008. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunkel EJS, Bakker JR, Myers RE, Oyesanmi O, Gomella LG. Biopsychosocial aspects of prostate cancer. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:85–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.41.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eton DT, Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS. Early quality of life in patients with localized prostate carcinoma - An examination of treatment-related, demographic, and psychosocial factors. Cancer. 2001;92:1451–1459. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1451::aid-cncr1469>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lubeck DP, Kim H, Grossfeld KC, Ray P, Penson DF, Flanders SC, Carroll PR. Health related quality of life differences between black and white men with prostate cancer: Data from the cancer of the prostate strategic urologic research endeavor. J Urol. 2001;166:2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayadevappa R, Johnson JC, Chhatre S, Wein AJ, Malkowicz SB. Ethnic variation in return to baseline values of patient-reported outcomes in older prostate cancer patients. Cancer. 2007;109:2229–2238. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jim HSL, Jacobsen PB. Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth in cancer survivorship: A review. Cancer J. 2008;14:414–419. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kangas M, Henry JL, Bryant RA. Posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer - A conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:499–524. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB, Breslau N. Epidemiological risk factors for trauma and PTSD. In: Yehuda R, editor. Risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1999. pp. 23–59. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breslau N. The Epidemiology of trauma, PTSD, and other posttrauma disorders. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10:198–210. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palesh O, Mustian K, Heckler C, Purnell J, Peppone L, Weiss M, Atkins JN, Dakhil SR, Spiegel D, Morrow G. A phase III randomized prospective trial of the effect of psychotherapy on distress in 287 prostate cancer patients: A URCC CCOP study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:9637. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Classen C, Butler LD, Koopman C, Miller E, DiMiceli S, Giese-Davis J, Fobair P, Carlson RW, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Supportive-expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer - A randomized clinical intervention trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:494–501. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zilberg NJ, Weiss DS, Horowitz MJ. Impact of Event Scale: A cross-validation study and some empirical evidence supporting a conceptual model of stress response syndromes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50:407–414. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen BL. Biobehavioral outcomes following psychological interventions for cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:590–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.70.3.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppelman LF. Manual: Profile of Mood States. Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heiney SP, McWayne J, Ford L, Carter C. Measurement in group interventions for women with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24:89–106. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer: A randomized outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:527–533. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780300039004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devins GM, Binik YM, Hutchinson TA, Hollowby DJ, Barre PE, Guttmand RD. The emotional impact of end stage renal disease: Importance of patients’ perception of intrusiveness and control. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1984;13:327–343. doi: 10.2190/5dcp-25bv-u1g9-9g7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devins GM, Edworthy SM, Seland TP, Klein GM, Paul LC, Mandin H. Differences in illness intrusiveness across rheumatoid-arthritis, end-stage renal-disease, and multiple-sclerosis. J Nervous Mental Dis. 1993;181:377–381. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenward MG, Roger JH. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics. 1997;53:983–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coffey SF, Gudmundsdottir B, Beck JG, Palyo SA, Miller L. Screening for PTSD in motor vehicle accident survivors using the PSS-SR and IES. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:119–128. doi: 10.1002/jts.20106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Himle JA, Baser RE, Taylor RJ, Campbell RD, Jackson JS. Anxiety disorders among African Americans, blacks of Caribbean descent, and non-Hispanic whites in the United States. J Anx Disorders. 2009;23:578–590. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alim TN, Charney DS, Mellman TA. An overview of posttraumatic stress disorder in African Americans. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:801–813. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baider L, Peretz T, De-Nour AK. Holocaust cancer patients: A comparative study. Psychiatry. 1993;56:349–355. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peretz T, Baider L, Ever-Hadani P, De-Nour AK. Psychological distress in female cancer patients with Holocaust experience. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994;16:413–418. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powe BD, Hamilton J, Hancock N, Johnson N, Finnie R, Ko J, Brooks P, Boggan M. Quality of life of African American cancer survivors - A review of the literature. Cancer. 2007;109:435–445. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krizek C, Roberts C, Ragan R, Ferrara JJ, Lord B. Gender and cancer support group participation. Cancer Pract. 1999;7:86–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thaxton L, Emshoff JG, Guessous O. Prostate cancer support groups: A literature review. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2005;23:25–40. doi: 10.1300/J077v23n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber BA, Sherwill-Navarro P. Psychosocial consequences of prostate cancer: 30 years of research. Geriatric Nurs. 2005;26:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]