Abstract

Autism is a neuro-developmental disorder characterized by deficits in social interaction and communication as well as restricted interests or repetitive behaviors. Cytogenetic studies have implicated large chromosomal aberrations in the etiology of approximately 5–7% of autism patients, and the recent advent of array-based techniques allows the exploration of submicroscopic copy number variations (CNVs). We genotyped a 14-year-old boy with autism, spherocytosis and other physical dysmorphia, his parents, and two non-autistic siblings with the Illumina Human 1M Beadchip as part of a study of the molecular genetics of autism and determined copy number variants using the PennCNV algorithm. We identified and validated a de novo 1.5Mb microdeletion of 14q23.2-23.3 in our autistic patient. This region contains 15 genes including spectrin beta (SPTB), encoding a cytoskeletal protein previously associated with spherocytosis, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 (MTHFD1), a folate metabolizing enzyme previously associated with bipoloar disorder and schizophrenia, pleckstrin homology domain-containing family G member 3 (PLEKHG3), a guanide nucleotide exchange enriched in the brain, and churchill domain containing protein 1 (CHURC1), homologs of which regulate neuronal development in model organisms. While a similar deletion has previously been reported in a family with spherocytosis, severe learning disabilities, and mild mental retardation, this is the first implication of chr14q23.2-23.3 in the etiology of autism and points to MTHFD1, PLEKHG3, and CHURC1 as potential candidate genes contributing to autism risk.

INTRODUCTION

Autism is considered one of the most highly heritable neuropsychiatric disorders (Ritvo et al., 1985; Bailey et al., 1995). While monogenic causes of rare syndromic forms of autism such as Rett Syndrome (Amir et al., 1999; Bienvenu et al., 2000) and tuberous sclerosis (Euro Chrom 16 Tuberous Scler Consort, 1993) have been identified, and large chromosomal abnormalities have been detected in 5–7% of autism patients (Kusenda & J. Sebat 2008), much of autism’s heritability remains to be determined. Toward determining other genetic components of the disorder, association of recurrent, heritable copy number variations (CNVs) with autism including 15q11-13 duplication, NRXN1 deletion, 22q11.21 duplication, and CNTN4 duplications and deletions recently have been reported (Glessner et al., 2009). In addition to autism’s heritable causes, spontaneous, de novo CNVs have been implicated as the genetic basis for many cases of autism (Sebat et al., 2007). Recent reports have identified novel autism candidate genes including RIMS3 (Kumar et al., 2009) FARP2, HDLBP and PASK (Felder et al., 2009) in screens for de novo CNVs in autism patients. Though these account for only a small proportion of autism heritability, they point toward CNVs affecting genes involved in neurological development and function as biological mechanisms contributing to autism etiology.

In this study we present a patient with autism and spherocytosis with a de novo 1.5 Mb deletion on chromosome 14q23.2-23 detected using a single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping array as part of a larger study of the molecular genetics of autism (Ma et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009). The deleted region reported here includes 15 protein-coding genes including SPTB, MTHFD1, PLEKHG3, and CHURC1. Importantly, a 2.21Mb deletion that removes the same genes previously has been reported in a 6-year-old boy, his mother, and maternal uncle, who all presented with severe learning difficulties, mild mental retardation and spherocytosis (Lybaek et al., 2008). Therefore, this deletion represents a CNV implicated with neurobehavioral phenotypes, including autism, and suggests MTHFD1, PLEKHG3, and CHURC1 as potential candidate genes contributing to autism risk.

METHODS

Ascertainment description

We report on a 14-year old boy with autism from a family ascertained through response to an advertisement for participation in a study of the molecular genetics of autism as previously described (Ma et al., 2009). In brief, patients with autism and their affected and unaffected family members were ascertained as part of the Collaborative Autism Project (CAP) through four clinical groups at the Hussman institute for Human Genomics (HIHG, Miami, Florida), University of South Carolina (Columbia, South Carolina), W.S. Hall Psychiatric Institute (Columbia, South Carolina) and Vanderbilt Center for Human Genetics Research (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee). The patient and his family were assessed per our study protocol which was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board. This protocol includes a physical evaluation, standardized diagnostic assessments, and review of all available medical history. Parental consent was provided and assent was obtained from the patient.

SNP genotyping and CNV detection

DNA was isolated from whole blood from the patient and all family members and was genotyped using the Illumina Human 1M Beadchip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Ascertainment of the patient and family, DNA extraction, genotyping, sample and SNP quality controls were performed as previously described (Ma et al., 2009). A previously reported patient with severe learning disabilities and mild mental retardation was examined using a 43kb resolution array-CGH (Lybaek et al., 2008) and follow-up SNP-genotyping was performed on the Affymetrix 6.0 GeneChip. Genotyping was performed at the Center for Medical Genetics and Molecular Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, March 2010.

The PennCNV algorithm (Wang et al., 2007) was employed to detect CNVs, and their positions were mapped onto the human genome using the NCBI Human Genome Build 36.1 (hg18). The PennCNV algorithm implements a hidden Markov model (HMM) that integrates multiple sources of information including log R ratio (LRR), B allele frequency (BAF), the distance between neighboring SNPs, and the population frequency of B allele to infer CNV calls by six different states. In addition, it can utilize family information to generate family-based CNV calls. Quality of the genome-wide intensity data is crucial for the accuracy of CNV detection. In this study, samples with the standard deviation (SD) of normalized intensity (LRR) < 0.35 were included. Intensity wave artifacts across genome, which roughly correlate with GC content resulting from hybridization bias of low full length DNA quantity, will also interfere with accurate inference of copy number variations. To correct for this effect only samples where the correlation of LRR to wave model ranged between −0.2<X<0.4 were accepted.

CNV validation

The deletion was validated using Applied Biosystems’ TaqMan Copy Number Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Two pre-designed assays, Hs02407029_cn and Hs07040258_cn were selected using the GeneAssist software available at http://www5.appliedbiosystems.com/tools/cnv/. Each assay was run in each of the 5 family members in quadruplicate 10µl reactions containing 1X TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, VIC-labeled RNaseP reference assay, and the FAM-labeled test assay. Reactions were performed in 40 wells of a 384 well plate on the ABI 7900HT Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and data collected with Applied Biosystems SDSv2.3. Data were analyzed with a manual Ct threshold of 0.2 and an automatic baseline and copy numbers were determined using CopyCaller software (Applied Biosystems) with RNaseP level as the calibrator for copy number.

RESULTS

Physical findings

A physical examination revealed a 14-year old male patient to be obese with macrocephaly (>95 centile) and with mild facial dysmorphism. Dysmorphic features included upslanting palpebral fissures, supraorbital lateral fullness, and thickened ears. His medical history is significant for episodes of tachycardia, acid reflux, and spherocytosis. The parents’ report times initial concerns regarding normal development to ~30 months. The patient sat unaided at ~6 months of age; walked at ~15 months; first words acquired at ~27 months.

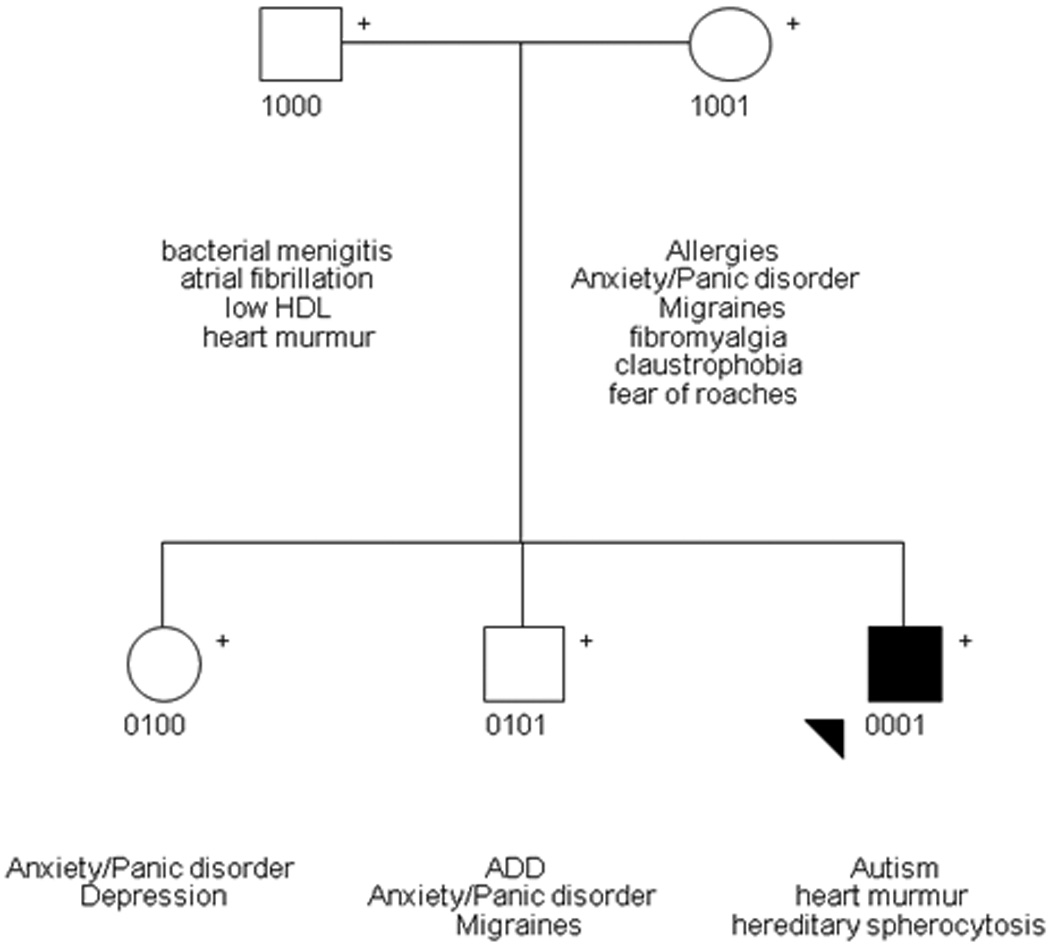

The patient’s spherocytosis was included in the medical history. The rest of the family medical history is negative for spherocytosis, autism, and mental retardation, but macrocephaly was present in the father. The mother and a sister and brother suffer from anxiety and panic disorder and the brother has diagnosed ADHD. The mother reported having migraines, and schizophrenia runs in the maternal family (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A pedigree depicting the family’s medical history reported here. The autistic proband is shaded in black and indicated with a black arrow.

Diagnostic-Psychometric findings

The patient was assessed using standard clinical methods including the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI-R) (Lord et al., 1994; Autism Genetics Resource Exchange 2008) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord et al., 1999). Both ADI-R and ADOS results yielded an autism classification with deficits in reciprocal social interaction, verbal communication, and behavior Intellectual assessment using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV (Wechsler 2003) places the patient in the borderline classification (Full Scale IQ=75). However, his test results were remarkable for significant discrepancies between his Perceptual Reasoning Index score (PRI=108) and other WISC-IV composites (i.e., ranging from 31–41 points). These are highly significant differences but suggest a relative and perhaps isolated strength in nonverbal abilities. Adaptive functioning as measured by Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow et al., 1984) was significantly impaired (VABS Adaptive Behavior Composite=49). All clinical measurements indicate a diagnosis of classical autism.

Cytogenetic studies

The patient’s chromosomal analysis revealed a normal G-banding pattern, indicating no chromosomal aberrations larger than approximately 5 Mb.

Molecular characterization

We genotyped the patient with autism, his parents, and two non-autistic siblings (Figure 1) on the Illumina Human 1M Beadchip (Ma et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009). Copy number analysis using PennCNV revealed 44 CNVs in the patient ranging in size from 333bp to 1.5Mb (Supplemental Table 1). These CNVs included four homozygous deletions, 29 heterozygous deletions, and 10 heterozygous duplications. Of these CNVs, 41 were inherited and three were de novo. Of the inherited CNVs, only six were not present in the Database of Genomic Variants (Iafrate et al., 2004). These six were small deletions, ranging in size from 7–70kb and only three overlapped with a known gene. The genes affected were ENOX1, encoding a mitochondrial membrane protein, SLC39A6, encoding a zinc transporter molecule, IFNAR1, and interferon receptor gene, and HIF1A, a hypoxia induced stress gene. None of these genes are predicted to have functions in neuronal processes or have been previously implicated in psychiatric disorders.

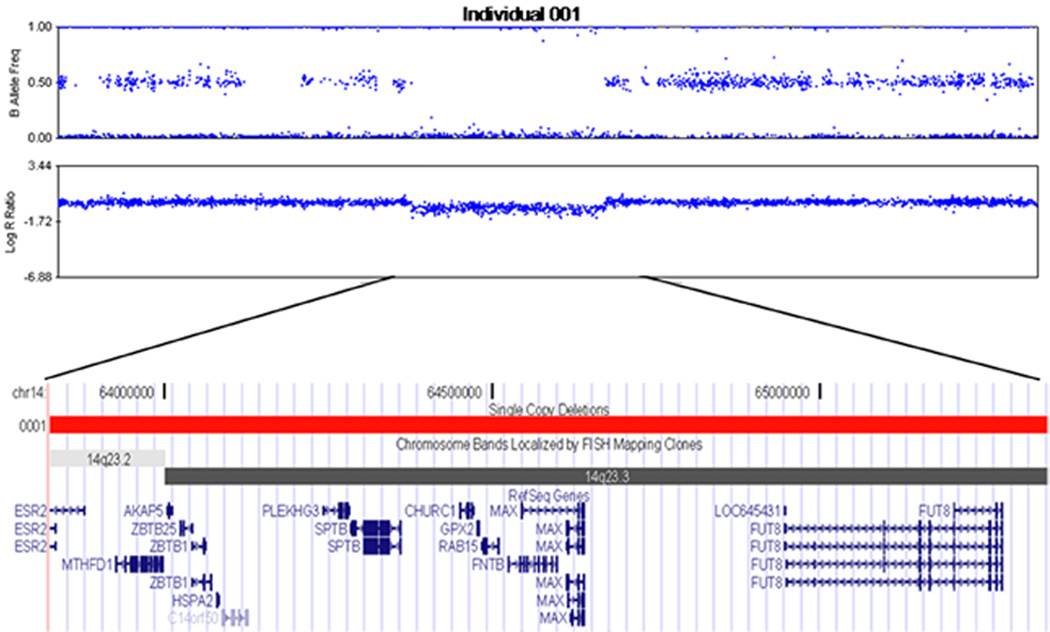

Of the three de novo CNVs, two were 18kb and 45kb duplications in regions of common genomic copy number variation that do not overlap with any known genes. The third was a 1.5Mb deletion of 14q23.2-23.3. The deletion spanned 572 SNP markers on the genotyping chip beginning at rs6573553 at 63.8Mb and ending at rs10149555 at 65.3Mb (Figure 2). The region contains 15 protein-coding genes, including SPTB, mutations in which have been implicated previously as causative for spherocytosis (Becker et al., 1993; Hassoun et al., 1996). Moreover, at least two genes, MTHFD1 and PLEKHG3, are potential autism candidate genes as they regulate neuronal development and function. As the contributions to autism of rare, de novo copy number variants affecting genes have been documented (Pinto et al.,2010; Sebat et al., 2007), we chose to focus on this deletion to examine its potential role in autism etiology.

Figure 2.

Plot of the B allele frequencies (BAF) and log R ratioes (LRR) values demonstrating a 1.5 Mb microdeletion at 14q23.2-23.3 in the patient. The normal copy number portions of the chromosome have three BAF genotype clusters, AA, AB, and BB genotypes, and LRR values near zero while the region of the deletion lacks heterozygosity and the LRR decreases. Within this deletion region, there are 15 protein-coding genes. Among them, the deleted gene SPTB is a well characterized gene causing spherocytosis. The region also contains PLEKHG3, a gene highly expressed in the brain and acting as a Rho-GEF, MTHFD1, a folate-metabolism gene that has been implicated in neural tube defect, heart defect, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, and CHURC1, a churchill domain containing gene about with unknown function, but which nominal association with autism in our study.

To investigate a possible association with autism in the deleted region, we examined 248 SNPs spanning the entire 1.5Mb deletion region that were genotyped in a 438-family autism dataset (Ma et al., 2009). Within the region, there were 21 SNPs with a suggestive significance of P-value of less than 0.05. Interestingly, the SNPs of lowest P values in the region cluster distinctly over two genes, PLEKHG3 and CHURC1 (Supplemental Table 2). In the PLEKHG3 region (chr14:64,240,946-64,280,813) there were 10 markers genotyped, 6 of which (rs732311, rs12895353, rs17180090, rs229648, rs1695769, and rs1695770) have P values less than 0.05. A similar cluster exists around the CHURC1 gene (chr14:64,450,893-64,471,666) where, of twelve markers, eight (rs1957425, rs12881353, rs1951488, rs7143432, rs4902336, rs1064108, rs11623705, and rs3742599) had P values less than 0.05. While these P values show a trend toward association, the 248 SNPs within this region separate into 51 distinct LD blocks, corresponding to a corrected P-value of 0.001, which none of the SNPs in either cluster meet.

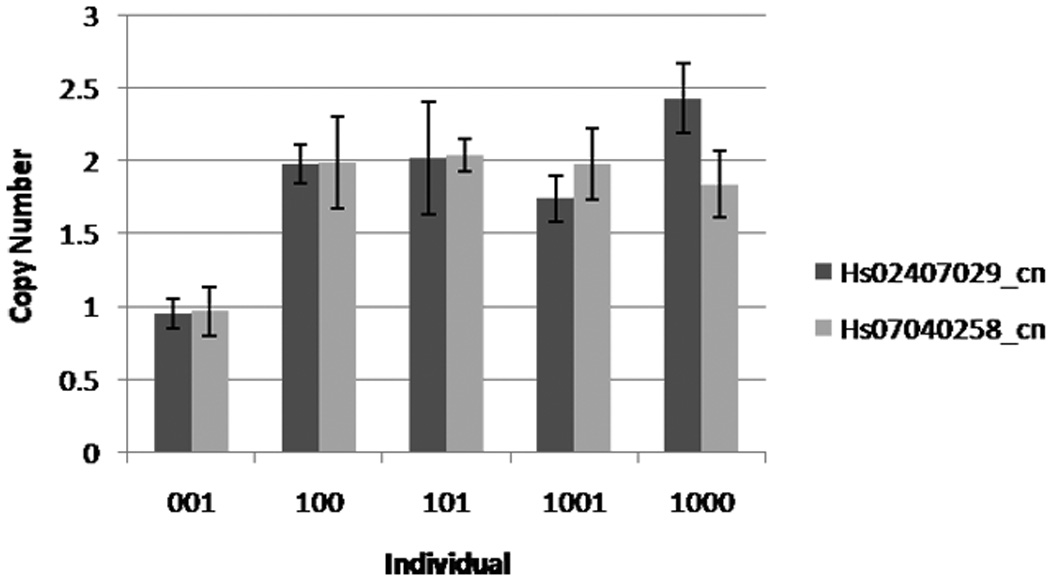

In order to confirm the de novo deletion‘s presence, and absence of it in other family members, we performed TaqMan real-time PCR validation reactions on this family. Two assays were chosen for validation, Hs_02407029_cn and Hs_07040258_cn, 6.6kb from the proximal end and 6.5kb from the distal end, respectively. These assays confirmed one copy of this region in patient 0001 and two copies in his siblings and parents (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

TaqMan confirmation of a deletion in patient 001. Bar height represents mean of four replicate reactions. Error bars represent mean ± SD of the four replicates.

The number of CNVs found in the other family members varied. The siblings, individuals 100 and 101, harbored 42 and 135 CNVs, respectively (Supplemental Table 1). The parents, individuals 1000 and 1001, maintained 60 and 276 CNVs, respectively (Supplemental Table 1). Interestingly, though the mother and two siblings have been diagnosed with anxiety disorder, there are no CNVs that segregate with this phenotype. Only one CNV, a 373kb duplication on chromosome 11q25 (chr11:133,853,184-134,227,062) is shared between the mother and all three children. The region on 11q25, however, is part of a common CNV region so is unlikely to contribute to either the anxiety or autism phenotype.

DISCUSSION

We present the clinical and molecular findings on a patient with mild physical dysmorphia, spherocytosis, and a diagnosis of autism. Molecular characterization of copy number variants in this patient via a high density SNP genotyping array reveals a de novo 1.5Mb deletion of chromosome 14q23.2-23.3. This is the first reported case of a deletion of this region being associated with autism. While a causal relationship cannot be definitively determined, there is evidence to suggest that this could be a novel autism risk region.

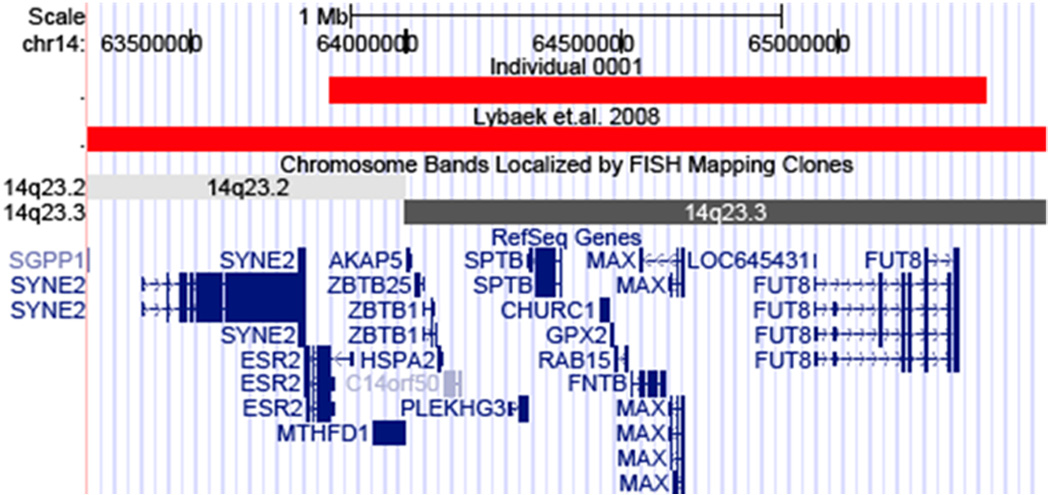

First, an inherited 2.1Mb deletion adjacent to a 14q21q23 paracentric inversion causing spherocytosis in a family has recently been described (Lybaek et al., 2008). The family members also had severe learning disabilities and mild mental retardation. The molecular characterization of the overlapping deleted regions in the present study and the previous report by Lybaek and collaborators is quite similar. The previous report used array-CGH to map the breakpoints of the deletion broadly from 63.22-63.39Mb to 65.31-65.55Mb. Follow-up SNP-genotyping refined these breakpoints from 63.26Mb to 65.48Mb for a size of 2.2Mb (data not shown). The deletion’s increased size, in comparison to this report, disrupts only one extra gene, spectrin repeat containing nuclear envelope 2 (SYNE2) (Figure 4). This gene has not been implicated in any neuronal function, suggesting that the same set of genes could be causing the psychiatric phenotypes described in both patients.

Figure 4.

The previously reported deletion in this region has breakpoints 500kb proximal and 130kb distal to that reported in this study. Except for the gene SYNE2, the two deletions are overlapping.

The patient’s clinical and physical features in this study resemble the phenotype of the index patient published previously (Lybaek et al., 2008). This original patient was a 6-year-old boy with spherocytosis, macrocephaly, severe learning disability, and diagnosed mild mental retardation. No formal testing for autism was performed. Our study’s patient also is a male sharing the physical characteristics of spherocytosis, macrocephaly and developmental delay, however, with a formal diagnosis of autism. It is possible that the phenotype difference between the two patients with respect to autism could be explained by a secondary mutation in combination with the detected deletion leading to the full autism phenotype.

Second, a causal relationship between this deletion and the spherocytosis phenotype can be made. Spherocytosis is generally an inherited autosomal dominant disorder with a positive family history in 75% of cases (Bolton-Maggs 2004). It is the most common form of inherited chronic hemolysis in North America, with incidence of 1/2000-5000. Symptoms include variable anemia, jaundice, and splenomegaly. Clinical diagnosis is based on clinical history, family history, physical examination (splenomegaly, jaundice) and laboratory data (full blood count, especially red cell indices and morphology, and reticulocyte count). Though this condition is not found in the family history of this patient, one of the deleted genes, the beta-spectrin (SPTB, OMIM 182870), has been implicated in several studies as causative for spherocytosis. Point mutations and smaller deletions have been implicated as causative functional mutations of this gene leading to spherocytosis (Lybaek et al., 2008; Goodman et al., 1982; Becker et al., 1993). In addition, a deletion involving the SPTB gene previously has been found to segregate with spherocytosis in a family (Lybaek et al., 2008). These data together suggest a strong association of this deletion with spherocytosis, and a possibility that the deletion also contributes to the autism phenotype.

Finally, at least two genes within the deleted region could be functionally relevant in autism as they regulate neuronal development and function. MTHFD1 is a folate metabolizing enzyme important in normal neurological development as mutations have been identified to increase risk for severe neural tube defects (Hol et al., 1998). Moreover, a recent study investigating the role of genes in the monoaminergic pathway, including MTHFD1, has shown association of polymorphisms in the gene to neuropsychiatric disorders including bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (Kempisty et al., 2007). PLEKHG3, a pleckstrin homology domain containing protein, is a second interesting candidate. It contains a guanide nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) domain important for Rho-dependent signal transduction. Interestingly, mutations and deletions of other GEF domain containing proteins have been implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders including X-linked mental retardation (Marco et al., 2008; Kutsche et al., 2000) and ataxia (Ishikawa et al., 2005). Moreover a clustering of SNPs with a suggestive association to autism from a GWAS study (Ma et al., 2009) point to PLEKHG3 as a possible new autism candidate gene. A similar clustering of SNPs around the CHURC1 gene may suggest this as a possible candidate gene as well. Though the gene’s function is not characterized in humans, a homolog in chickens regulates neuronal cell differentiation during embryogenesis (Sheng et al., 2003) making this another possible candidate gene. While it is unclear if haploinsufficiency of these genes is causative of autism, their functions offer promising candidates.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. All CNVs identified in each family member depicted in the pedigree in Figure 2. The file is an .xls file containing 5 tabs, one for each family member. Every CNV identified by the PennCNV algorithm is listed in the columns listing the position of the CNV, the number of SNPs genotyped within the CNV, the length in basepairs of the variation, and whether there is a loss or gain of copy in the region.

Supplemental Table 2. Significance of all SNPs genotyped within the 14q23.2-23.3 deletion region. The file is an .xls file listing all the SNPs genotyped on the Illumina 1M beadchip within the deletion region as well as the genomic position and the P-value as determined by a genome wide association study. P-values of nominal significance (P<0.05) are bolded and italicized. The blocks of nominal significance around the PLEKHG3 and CHURC1 genes are indicated in a black box with the name of gene.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients with autism and their family members who participated in this study and personnel at the Hussman Institute for Human Genomics. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (5R01MH080647-13 and 5P01NS026630-20) and by a gift from the Hussman Foundation. A subset of the participants was ascertained while Dr. Pericak-Vance was a faculty member at Duke University.

Grant Sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health; Grant Number: 5R01MH080647-13

Grant Sponsor: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Grant Number: 5P01NS026630-20

Grant Sponsor: The Hussman Foundation

LITERATURE CITED

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nature Genetics. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autism Genetics Resource Exchange. 2008 http://www.agre.org/

- Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, Bolton P, Simonoff E, Yuzda E, et al. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:63–77. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker PS, Tse WT, Lux SE, Forget BG. Beta spectrin kissimmee: a spectrin variant associated with autosomal dominant hereditary spherocytosis and defective binding to protein 4.1. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;92:612–616. doi: 10.1172/JCI116628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu T, Carrie A, de Roux N, Vinet MC, Jonveaux P, Couvert P, Villard L, et al. MECP2 mutations account for most cases of typical forms of Rett syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 2000;9:1377–1384. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton-Maggs PH. Hereditary spherocytosis; new guidelines. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2004;89:809–812. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.034587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euro Chrom 16 Tuberous Scler Consort. Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell. 1993;75:1305–1315. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder B, Radlwimmer B, Benner A, Mincheva A, Todt G, Beyer KS, et al. FARP2, HDLBP and PASK are downregulated in a patient with autism and 2q37.3 deletion syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 2009;149A:952–959. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glessner JT, Wang K, Cai G, Korvatska O, Kim CE, Wood S, et al. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature. 2009;459:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature07953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SR, Shiffer KA, Casoria LA, Eyster ME. Identification of the molecular defect in the erythrocyte membrane skeleton of some kindreds with hereditary spherocytosis. Blood. 1982;60:772–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassoun H, Vassiliadis JN, Murray J, Yi SJ, Hanspal M, Johnson CA, et al. Hereditary spherocytosis with spectrin deficiency due to an unstable truncated beta spectrin. Blood. 1996;87:2538–2545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hol FA, van der Put NM, Geurds MP, Heil SG, Trijbels FJ, Hamel BC, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of the gene encoding the trifunctional enzyme MTHFD methylenetetrahydrofolate-dehydrogenase, methenyltetrahydrofolate-cyclohydrolase, formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase) in patients with neural tube defects. Clinical Genetics. 1998;53:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1998.tb02658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, Listewnik ML, Donahoe PK, Qi Y, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nature Genetics. 2004;36:949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa K, Toru S, Tsunemi T, Li M, Kobayashi K, Yokota T, et al. An autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia linked to chromosome 16q22.1 is associated with a single-nucleotide substitution in the 5' untranslated region of the gene encoding a protein with spectrinrepeat and Rho guanine-nucleotide exchange-factor domains. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;77:280–296. doi: 10.1086/432518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempisty B, Sikora J, Lianeri M, Szczepankiewicz A, Czerski P, Hauser J, et al. MTHFD 1958G>A and MTR 2756A>G polymorphisms are associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatric Genetics. 2007;17:177–181. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328029826f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar RA, Sudi J, Babatz TD, Brune CW, Oswald D, Yen M, et al. A de novo 1p34.2 microdeletion identifies the synaptic vesicle gene RIMS3 as a novel candidate for autism. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2009;47:81–90. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.065821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusenda M, Sebat J. The role of rare structural variants in the genetics of autism spectrum disorders. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2008;123:36–43. doi: 10.1159/000184690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsche K, Yntema H, Brandt A, Jantke I, Nothwang HG, Orth U, et al. Mutations in ARHGEF6, encoding a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rho GTPases, in patients with X-linked mental retardation. Nature Genetics. 2000;26:247–250. doi: 10.1038/80002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore P, Risi S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-WPS. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, LeCouteur A. Autism diagnostic interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lybaek H, Oyen N, Fauske L, Houge G. A 2.1 Mb deletion adjacent but distal to a 14q21q23 paracentric inversion in a family with spherocytosis and severe learning difficulties. Clinical Genetics. 2008;74:553–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Salyakina D, Jaworski JM, Konidari I, Whitehead PL, Andersen AN, et al. A genome-wide association study of autism reveals a common novel risk locus at 5p14.1. Annals of Human Genetics. 2009;73:263–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco EJ, Abidi FE, Bristow J, Dean WB, Cotter P, Jeremy RJ, et al. ARHGEF9 disruption in a female patient is associated with X linked mental retardation and sensory hyperarousal. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2008;45:100–105. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.052324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D, Pagnamenta AT, Klei L, Anney R, Merico D, Regan R, et al. Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2010;466:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature09146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritvo ER, Freeman BJ, Mason-Brothers A, Mo A, Ritvo AM. Concordance for the syndrome of autism in 40 pairs of afflicted twins. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:74–77. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D, Troge J, Lese-Martin C, Walsh T, et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2007;316:445–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1138659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng G, dos Reis M, Stern CD. Churchill, a zinc finger transcriptional activator, regulates the transition between gastrulation and neurulation. Cell. 2003;115:603–613. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Balla D, Cicchetti D. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Interview Edition. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Zhang H, Ma D, Bucan M, Glessner JT, Abrahams BS, et al. Common genetic variants on 5p14.1 associate with autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2009;459:528–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hadley D, Liu R, Glessner J, Grant SF, et al. PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Research. 2007;17:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV) San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. All CNVs identified in each family member depicted in the pedigree in Figure 2. The file is an .xls file containing 5 tabs, one for each family member. Every CNV identified by the PennCNV algorithm is listed in the columns listing the position of the CNV, the number of SNPs genotyped within the CNV, the length in basepairs of the variation, and whether there is a loss or gain of copy in the region.

Supplemental Table 2. Significance of all SNPs genotyped within the 14q23.2-23.3 deletion region. The file is an .xls file listing all the SNPs genotyped on the Illumina 1M beadchip within the deletion region as well as the genomic position and the P-value as determined by a genome wide association study. P-values of nominal significance (P<0.05) are bolded and italicized. The blocks of nominal significance around the PLEKHG3 and CHURC1 genes are indicated in a black box with the name of gene.