Abstract

The OPTN classifies high infectious risk donors (HRDs) based on criteria originally intended to identify people at risk for HIV infection. These donors are sometimes referred to as "CDC high risk donors" in reference to the CDC-published guidelines adopted by the OPTN. However, these guidelines are also being used to identify deceased donors at increased risk of window period (WP) hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, although not designed for this purpose. The actual risk of WP HCV infection in HRDs is unknown.We performed a systematic review of 3,476 abstracts and identified 37 eligible estimates of HCV incidence in HRD populations in the United States/Canada. Pooled HCV incidence was derived and used to estimate the risk of WP infection for each HRD category. Risks ranged from 0.26–300.6 per 10,000 donors based on WP for ELISA and 0.027–32.4 based on nucleic acid testing (NAT). Injection drug users were at highest risk (32.4 per 10,000 donors by NAT WP), followed by commercial sex workersand donors exhibiting high risk sexual behavior (12.3:10,000),men who have sex with men (3.5:10,000), incarcerated donors (0.8:10,000), donors exposed to HIV infected blood (0.4:10,000), and hemophiliacs (0.027:10,000). NAT reduced WP risk by approximately 10-fold in each category.

Keywords: organ utilization, NAT, high risk donor, deceased donor transplantation, hepatitis C

INTRODUCTION

In 1985(1), and later updated in 1994 (2), the Public Health Service (PHS) developedguidelines to identify persons at increased risk for HIV infection. These guidelines were published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and adopted by the OPTN to identify deceased organ donors at increased risk of infectious transmission. Currently, any donor falling into one or more of the 7 specified behavioral categories (Table 1) is classified as a high risk donor (HRD) and subject to additional OPTN policies. Despite significant controversy surrounding their use, approximately 9% of donors where at least one organ is recovered are categorized as HRDs (3).

Table 1.

Categories of behavior leading to classification of High Risk Donor

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| MSM | men who have had sex with another man in the preceding 5 years |

| IDU | persons who report nonmedical intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous injection of drugs in the preceding 5 years |

| Hemophiliac | persons with hemophilia or related clotting disorders who have received human derived clotting factor concentrates |

| CSW | men and women who have engaged in sex in exchanged for money or drugs in the preceding 5 years |

| High Risk Sex | persons who have had sex in the preceding 12 months with any person described in items 1–4 above or with a person known or suspected to have HIV infection |

| Exposed to HIV | persons who have been exposed in the preceding 12 months to known or suspected HIV infected blood through percutaneous inoculation or through contact with an open wound, non-intact skin, or mucous membrane |

| Incarcerated | inmates of correctional systems |

MSM = Men who have sex with other men, IDU = injection drug user, CSW = Commercial Sex Worker, HIV = Human Immunodeficiency Virus

While the originally intended purpose of the HRD guidelines was to identify those at risk of prevalent infection, in practice this is not a relevant concern. UNOS mandates HIV and HCV antibody testing for all deceased donors and, as such, prevalent infections are detected (4, 5). However, no serologic test can detect infections that occurred very recently, so theconcern isincident infection occurring during the window period (WP), the time between acquisition of infection and serologic detectability. This scenario will likely result in a false-negative test result and transmission to the recipient(6–8). As such, the HRD criteria are instead used as surrogate criteria to identify persons at risk of recently acquired infection

The PHS/CDC guidelines have not only been extrapolated in practice from prevalent HIV to WP incident HIV infection, but they have also been used as a default proxy for identifying deceased donors at risk for WP incident infections with hepatitis C virus (HCV)(9).While HIV and HCV share several modes of transmission, their epidemiology is not identical. Both are blood-borne illness that can bespread parenterally(10, 11); however HCV transmission is thought to be more efficient by this route than HIV infection. Sexual transmission is considered one of the primary drivers of the HIV epidemic(12); in contrast, sexual transmission of HCV is thought to be extremely inefficient, if at all relevant(13).Several studies of HCV discordant couples found little to no evidence of sexual transmission(14, 15). Having multiple sexual partners may increase the risk of HCV infection(16, 17); however, it is unclear whether this is a real effect or the result of other confounding risk behaviors(18).Three of the HRD categories are based on sexual behaviors (MSM, CSW, and high risk sexual behavior). It is unclear whether these categories are truly indicative of an increased risk for HCV.

An additional problem with expanding guidelines intended for HIV to HCV is that the two diseases have distinct clinical courses with different implications for serologic testing. While antibodies to HIV are typically produced within 3 weeks of infection (19), HCV antibody formation does not occur for 8–12 weeks (20), making the WP between acquisition of infection and serologic detectability by Enzyme-Linked Immuno- Assay (ELISA), an antibody-based method, much longer for HCV (approximately 66 days for HCV compared with 22 for HIV). Nucleic acid testing (NAT) is an alternative method based on detection of viral particles that shortens the WP to approximately 1 week (21). While antibody testing is mandated for all donors (22), the decision to use NAT is left to the individual Organ Procurement Organization (OPO). A survey of OPOs performed in 2008 found that 48.3% performed HCV NAT for all donors and an additional 20.7% performed it under certain circumstances (i.e. for HRDs only, when requested by the transplant center) (23). NAT is not universally used because it is more expensive, time consuming, and thought to have a higher rate of false positives compared to ELISA (9, 24). However, given that HCV NAT decreases the WP by several months, the benefits for HCV detection may outweigh the risks in a more pronounced way than with HIV.

We hypothesized that the risk of HCV WP infection would be higher than the risk of HIV for some categories and significantly lower for others, and that quantifying these risks would be essential for informed clinical decision-making with regards to HRDs. The goals of our study were to (1) estimate the incidence and variance of HCV infection within each category of HRD behavior, and (2) estimate the risk of HCV WP infection, by ELISA and NAT, within each category of HRD behavior.

METHODS

Systematic Review: Study Selection and Search Strategy

We performed a PubMed search on November 27th, 2008 for studies of HIV or HCV incidence or prevalence (see appendix for details of search). Studies were eligible for inclusion in our systematic review if they presented an original estimate of HIV or HCV prevalence or incidence in a population located in the United States or Canada on or after January 1, 1995. We chose this cut-off for two major reasons: (1) accurate screening tests for HCV were not developed until the early 1990s and screening of the blood supply dramatically changed the epidemiology of HCV, particularly among hemophiliacs (25); and (2) the dynamics of HIV transmission, and thus HIV/HCV coinfection, likely changed with the introduction of highly-active antiretroviral therapy. Two independent reviewers and two adjudicators performed a systematic review for manuscripts meeting inclusion criteria and mined references of a 20% sample of eligible studies to identify any studies that might have been missed (26). Since incidence studies require significant resources for the identification and follow-up of large numbers of individuals, we hypothesized that many studies would have NIH funding. As such, we searched the NIH grant database for keywords"HIV" or "HCV" and "Incidence" funded after 1995 in order to identify any studies that might have been missed by other methods..

Meta-Analysis: Inclusion Criteria

The goal of this meta-analysis was to estimate HCV incidence in HRD populations; as such only a subset of studies included in the systematic review were eligible for our meta-analysis. Eligible studies reported an estimate of HCV incidence in one of the 7 HRD populations outlined in Table 1. Studies reporting HCV prevalence estimates were included for HRD behavioral categories for which multiple incidence studies were unavailable Approximately 80–85% of persons exposed to HCV develop chronic infection with persistent HCV-RNA positivity while the remaining 15–20% eventually clear the virus(27). However, even those with eventual clearance were likely infectious during the acute phase, the point of interest when the concern is WP infection.As such,for consistency,it was decideda priori that only studies using HCV antibody testing only or a combination of HCV antibody and RNA (where everyone was tested with both and considered infected if positive by either method) would be included; fortunately, there were no studies in HRD populations that used only RNA without antibody testing, so no studies had to be excluded. Estimates lacking a denominator (for example, reported HCV cases over the total population) were also excluded.

Data Abstraction

Data from each eligible study were abstracted by at least 2 independent reviewers and disagreements were adjudicated as previously described (26). The following data were abstracted from each article: recruitment dates, county, state, city, and location where recruitment took place, sampling method (convenience, target, random sample, chain/referral sampling), inclusion criteria, testing method, number of patients approached, number eligible, number tested, number positive by HCV antibody and number positive by HCV RNA. We abstracted the overall HCV incidence and prevalence for each article, in addition to risk-stratified sub-estimates if the risk factor was one of the HRD criteria. For incidence studies, the number of seronegative patients eligible for follow-up, the number tested at follow-up, the number of seroconversions, incidence rate, and total number of person-years at risk were abstracted, back-calculated using other data from the manuscript, or obtained directly from the study authors.

Meta-Analysis

Any study of HCV incidence among persons demonstrating one of the HRD behavioral risk factors was eligible for inclusion in our meta-analysis. When we were unable to find multiple incidence studies in a behavioral category, we included all prevalence studies in this category and estimated incidence from prevalence as described below. Each HCV incidence estimate was classified as falling into one of the categories, falling into multiple categories, or other. All studies in the same behavioral category that took place in the same geographic location were flagged and re-examined to ensure that the estimate were not derived from the same cohort and could be combined without fear of counting the same individuals multiple times. Pooled incidence estimates were obtained by summing the person-years and number of HCV seroconversions for each study within categories of HRD behavior. Persons were considered to have seroconverted if they became HCV antibody or HCV-RNA positive over the course of the study. Poisson exact 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each pooled incidence estimate using Stata 11/MP (College Station, TX).

Estimating Incidence From Prevalence

Incidence studies are challenging and resource intensive, requiring recruitment, follow-up, and serologictesting of large cohorts over long periods of time. Furthermore, three of the HRD behavioral categories involve sexual risk factors, widely considered to be an inefficient mode of HCV transmission. As such, there have been few incidence studies of HCV specifically aimed at populations with sexual risk factors. To account for this, data were abstracted from HCV prevalence studies in each category, and methods for estimating the incidence of a disease in a given population based on its prevalence were used when insufficient incidence studies were found(28).Briefly, we compared the ratio of incidence to prevalence in an HRD population where both were known, in order to solve for the unknown incidence value using the pooled prevalence estimate in the HRD population of interest:

Upper and lower bounds for the unknown incidence were computed by substituting the upper and lower bounds of the Poisson Exact 95% CI computed for HCV incidence in IDUs.

Estimating the Risk of Window Period Infection

Pooled incidence estimates from the meta-analysis were then used to calculate a per-day incidence rate (IR) and then combined with WP duration to calculate the probability of a WP infection using iterative conditional probabilities as shown in the following equation(26):

Upper and lower bounds on the probability of a WP infection were calculated by using the upper and lower bounds of the Poisson exact 95% CIs around the pooled incidence rates for the pooled incidence value in the equation above.

Since very few studies of hemophiliacs were available since recent significant improvements in blood screening (29), estimates in hemophiliacs were determined based on studies of HCV incidence in blood donors described previously in more detail(26). Briefly, we used the WP of the serologic tests used to screen blood donors and HCV incidence in this population to calculate the residual risk of HCV in the blood supply:

We then used this residual risk to calculate the probability that a hemophiliac might contract HCV, making the assumption that 1 unit of blood per day was transfused for the entire duration of the HCV NAT WP:

Estimates in persons exposed to HIV infected blood percutaneously or mucocutaneously

This category, taken literally from the HRD guidelines (based on the mechanism that percutaneous exposure to HIV infected blood might transmit HIV), makes little sense in the context of HCV (since percutaneous exposure to HIV infected blood will not, by mechanism, transmit HCV). However, to be most conservative, we felt the best approach to risk estimation in this category was to combine estimates of HCV infectious risk per percutaneous exposure and estimates of HCV prevalence among persons infected with HIV. A recent multicenter study in Italy followed persons percutaneously exposed to HCV infected blood over 55 hospitals and calculated the risk of HCV transmission per exposure involving blood infected with HCV only as well as blood coinfected with HIV and HCV. They found that the rate of HCV transmission was over twice as high when the blood was HIV and HCV coinfected as when the blood was infected with HCV only (0.35% versus 0.85%). As such we used an estimate of0.85% per exposure in our calculations. To estimate the percent of HIV infected blood coinfected with HCV, we compiled prevalence studies of HCV infection among persons with HIV. We used the per needlestick estimate for coinfected blood combined with the probability that HIV infected blood is coinfected with HCV to calculate the risk of WP infection, assuming only one exposure event occurred, and there was equal probability of the event occurring on any day in the year prior to death.

RESULTS

Systematic review

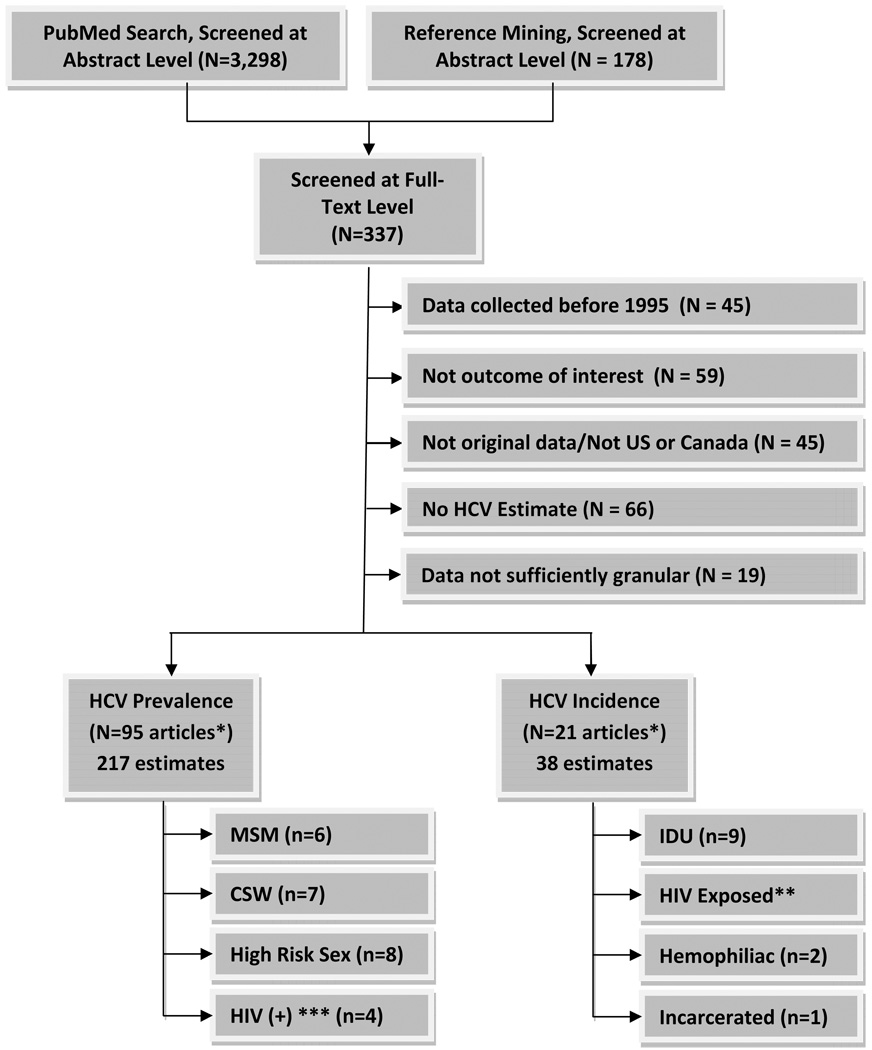

After screening, 337 articles were eligible for inclusion at the full-text level (Figure 1) and 103 were eligible for data abstraction. For the meta-analysis, these were further narrowed to 37 unique estimates among populations meeting HRD behavioral criteria.

Figure 1. Search/Selection.

* Some studies reported both HCV prevalence and incidence; unique studies included totaled 103

** A systematic review was recently performed on this topic and the estimates reported in this review were used to calculate the risk of WP HCV infection in donors exposed to HIV infected blood

*** Used to calculate the probability that HIV infected blood was coinfected with HCV

Men Who Have Sex With Men

Six eligible prevalence studies were found in this category, for a total pooled sample size of 1341 participants (Table 3)(30–35). The incidence was estimatedusing established techniques(28)based on prevalence among IDUs as the reference category (32–65). Incidence was calculated to be 1.8 per 100 person-years (range 1.7–2.0, Table 2). Per 10,000 donors, the estimated risk of WP infection was 32.5 (range 30.7–36.1) with ELISA and 3.5 (range 3.3–3.8) with NAT.

Table 3.

Studies of HCV Prevalence Among Men who Have Sex with Men

| Study | Location | Population | Recruitment | # Tested | # Infected | Percent Infected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hwang et al 2006 (33) | Houston, Texas | College students from 8 campuses who identify as MSM | Target | 142 | 6 | 4.2 |

| Hammer et al 2003 (32) | San Francisco, California | HIV counseling testing patients who received multiple tests and identify as MSM and do not report IDU | Convenience | 746 | 15 | 2.0 |

| Rosenberg et al 2001 (34) | Connecticut, Maryland, New Hampshire, North Carolina | Patients at mental health treatment centers who identify as MSM | Convenience | 108 | 22 | 20.3 |

| Dominitz et al 2005 (31) | United States | Patients at VA medical centers who identify as MSM | Cluster Sampling | 47 | 1 | 2.1 |

| Cohen et al 2006 (30) | Boston, MA | Patients receiving care at a free clinic who identified as MSM | Convenience | 218 | 25 | 11.5 |

| Roy et al 2001 (35) | Vancouver, Canada | Homeless street youth who report a homosexual partner | Target | 80 | 17 | 21.3 |

Table 2.

Risk per 10,000 of an HCV infection occurring during the Window Period, by ELISA and NAT

| HRD Category | # Patients | # HCV Seroconverted or Prevalent |

Person- Years |

Pooled Incidence (95% CI) (per 100 pys) |

ELISA WP=66 days |

NAT WP = 7 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM | 1341 | 86* | ** | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) |

32.5 (30.7–36.1) |

3.5 (3.3–3.8) |

| IDU | 1955 | 520 | 3081.4 | 16.9 (15.5–18.4) |

300.6 (276.1–326.8) |

32.4 (29.7–35.3) |

| Hemophiliac | 23,952,635 | 103 | 5,651,063 | 0.0018 (0.0015–0.0022) |

0.26 (0.22–.32) |

0.027 (0.023–0.034) |

| Commercial Sex Worker | 678 | 152* | ** | 6.4 (5.9–7.0) |

114.9 (105.9–125.6) |

12.3 (11.3–13.4) |

| Sex with a partner in categories 1–4 | 1361 | 301* | ** | 6.4 (5.8–6.9) |

114.9 (104.2–123.8) |

12.3 (11.1–13.2) |

| HIV Exposed through blood | 6736 | 1674* | *** | 0.0085**** (0.0018–0.0247) |

4 (0.9–11.1) |

0.4 (0.09–1.2) |

| Incarcerated***** | 337 | 2 | 550.9 | 0.4 (0.04–1.3) | 7.2 (0.7–23.5) |

0.8 (0.08–2.5) |

Number of prevalent, not incident infections.

Prevalence used to estimate incidence using methods previously described

Prevalence of HCV among HIV positive persons was estimated and combined with an estimate of per blood exposure risk of HCV to estimate WP infection in this category

Probability of infection per exposure

Only one study of intra-prison incidence available

Injection Drug Users

Nine studies of HCV incidence in IDUs were identified for a total pooled sample size of 1955 participants(Table 4)(43, 45, 47, 49, 52, 54, 66–68). Incidence rates ranged widely from 0.68 to 35.9 per 100 person-years; however, when limiting to studies that only recruited persons who reported injection in the preceding 6 months, the range was 10 to 35.9 per 100 person-years. Pooled HCV incidence among IDUs was 16.9 per 100 person-years (range 15.5–18.4, Table 2). Per 10,000 donors, the estimated risk of WP infection was 300.6 (range 276.1–326.8) with ELISA and 32.4 (range 29.7–35.3) with NAT.

Table 4.

Studies of HCV Incidence in Injection Drug Users

| Study | Location | Population | Recruitment | # in Study |

# Infected |

Person Years |

Incidence Rate (per 100 pys) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hahn et al, 2002 (67) | San Francisco, California | Injection drug users ages 18– 30 who injected at least once in past month | Target | 195 | 48 | 191.2 | 25.1 |

| Des Jarlais et al 2003 (43) | New York City, New York | Injection drug users ages 18– 30 who reported injection at least once in past 6 months | Target | 141 | 25 | 120.8 | 20.7 |

| Patrick, et al 2001 (52) | Vancouver, Canada | Injection drug users ages 18– 30 who injected at least once in past month | Target | 155 | 62 | 213.1 | 29.1 |

| Thorpe et al. 2002 (68) | Chicago, Illinois | Injection drug users ages 18– 30 who injected at least once in past month | Target | 353 | 29 | 290 | 10 |

| Roy et al 2007 (54) | Ontario and Quebec, Canada | Injection drug users who injected at least once in past 6 months and were visiting centers providing sterile injection equipment | Convenienc e | 543 | 199 | 734.3 | 27.1 |

| Augenbraun et al, 2003 (66) | New York City NY, DC, Los Angeles CA, San Francisco CA, Chicago IL | Women utilizing HIV primary care sites, drug treatment, or outreach facilities who reported ever injecting drugs | Convenienc e | Unk. | 2 | 293.0 | 0.68 |

| Hall et al, 2004 (49) | San Francisco CA | HIV positive homeless persons recruited from homeless shelters, free lunch programs, or residential hotels who reported injection drug use in past 30 days | Target | 22 | 8 | 47.6 | 16.8 |

| Hagan et al 2004 (47) | Seattle, WA | Injection drug users who reported injection at least once in previous year; recruited from drug treatment facilities | Convenience | 484 | 134 | 1155.2 | 11.6 |

| Fuller et al 2004 (45) | New York City NY | Injection at least once in past 2 months | Target | 62 | 13 | 36.2 | 35.9 |

Hemophiliacs

Results from 23,952, 635 individual blood donations from Canada and the United States were included in the pooled estimate (Table 5)(69, 70). HCV incidence in Canada was 0.00163 per 100 person-years and in the United States was 0.00189 per 100 person-years. The pooled HCV incidence among blood donors was estimated to be 0.0018 per 100 person-years (range 0.22–0.32, Table 2). Per 10,000 donors, the estimated risk of WP infection was 0.26 (range 0.22–0.32) with ELISA and 0.027 (0.023–0.034) with NAT.

Table 5.

Studies of HCV Incidence in Blood Donors

| Study | Location | Population | Recruitment | # in Study | # Infected |

Person Years |

Incidence Rate (per 100 pys) |

Residual Risk** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obrien et al, 2007 (70) | Canada | Donors who made at least 2 donations within 3 years of each other | 100% of defined population | 4,140,862* | 24 | 1,469,06 3 | 0.00163 | 0.0356 |

| Dodd et al, 2002 (69) | United States | Blood donors | 100% of defined population | 19,811,809 * | 79 | 4,182,00 0 | 0.00189 | 0.0414 |

WP given as 8 days (range 6.8–9.2)

Residual risk is the risk per 100,000 donors of a recent HCV infection occurring during the window period and being undetected by conventional blood screening measures.

Commercial Sex Workers

Seven prevalence studiesof CSWs were identified, for a total pooled sample size of 678 participants (Table 6)(31, 34, 35, 39, 51, 60, 63). Using methods described above (see MSM category above), incidence was estimated to be 6.4 per 100 person-years (range 5.9–7.0, Table 2). Per 10,000 donors, the estimated risk of HCV WP infection was 114.9 (range 105.9–125.6) with ELISAand 12.3 (range 11.3–13.4) with NAT.

Table 6.

Studies of HCV Prevalence Among Commercial Sex Workers

| Study | Location | Population | Recruitment | # Tested | # Infected | Percent Infected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bollepalli et al 2007 (39) | Phoenix, AZ | HIV positive patients recruited from 2 clinics catering to patients with HIV or liver disease who report having sex in exchange for money or drugs | Convenience | 38 | 20 | 52.6 |

| Weisbord et al 2003 (63) | Miami, FL | STI clinic patients who reported exchanging sex for drugs or money | Convenience | 79 | 9 | 11.4 |

| Rosenberg et al (34) | Connecticut, New Hampshire, Maryland, North Carolina | Patients receiving care at mental health treatment clinics diagnosed with severe mental illness who report ever having engaged in prostitution | Double check | 190 | 50 | 26.3 |

| Page-Shafer et al 2002 (51) | Alameda, San Francisco, San Joaquin, and San Mateo counties California | Women recruited from low income neighborhoods who reported exchanging sex for drugs or money | Cluster Sampling | 207 | 28 | 13.5 |

| Dominitz et al 2005 (31) | United States | Patients at VA medical center who reported exchanging sex for drugs | Cluster Sampling | 12 | 3 | 25.0 |

| Roy et al 2001 (35) | Montreal, Canada | Homeless street youths ages 14–25 who report engaging in prostitution | Target | 107 | 24 | 22.4 |

| Tabibian et al 2008 (60) | Los Angeles, CA | Psychiatric inpatients at VA medical center who report bartering sex | Convenience | 45 | 18 | 40.0 |

High Risk Sexual Behavior

Eighteligible prevalence studies were identified, with a total pooled sample size of 1361 participants (Table 7)(31, 33, 35, 39–41, 51, 60). Incidence was estimated to be 6.4 per 100 person-years (range 5.8–6.9, Table 2). Per 10,000 donors, the estimated risk of HCV WP infection was 114.9 (range 104.2–123.8) with ELISA and 12.3 (range 11.1–13.2) with NAT.

Table 7.

Studies of HCV Prevalence Among Persons Engaging in High Risk Sexual Behavior

| Study | Location | Population | Recruitment | # Tested | # Infected | Percent Infected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Briggs et al 2001 (40) | San Francisco, CA | Veterans seeking care at a VA medical center who report having sex with a prostitute | Random Sample | 540 | 116 | 21.5 |

| Hwang et al 2006 (33) | Houston, TX | College students recruited from 8 campuses who report having sex with an injection drug users | Target | 206 | 18 | 8.7 |

| Bollepalli et al 2007 (39) | Phoenix, AZ | HIV positive patients at 2 urban clinics catering to those with HIV or liver disease who report having sex with an injection drug user | Convenience | 79 | 43 | 54.4 |

| Page-Shafer et al 2002 (51) | Alameda, San Francisco, San Joaquin, and San Mateo counties California | Women recruited from low income neighborhoods who reported having sex with an injection drug user | Cluster Sampling | 176 | 22 | 12.5 |

| Dominitz et al 2005 (31) | United States | Patients at VA medical centers who report unprotected sex with an injection drug user | Cluster Sampling | 48 | 18 | 37.5 |

| Roy et al 2001 (35) | Montreal, Canada | Homeless street youth who report having sex with an injection drug user | Target | 222 | 42 | 18.9 |

| Roy et al 2001 (35) | Montreal, Canada | Homeless street youth who report having sex with an HIV positive person | Target | 24 | 7 | 29.2 |

| Brillman et al 2002 (41) | Southwestern United States | Emergency room patients at a teaching hospital who are medically stable and report sex with an injection drug user | Convenience | 20 | 10 | 50.0 |

| Tabibian et al 2008 (60) | Los Angeles, CA | Psychiatric inpatients at VA hospitals who report having sex with an injection drug user | Convenience | 17 | 11 | 64.7 |

| Tabibian et al 2008 (60) | Los Angeles, CA | Psychiatric inpatients at VA hospitals who report having sex with a prostitute | Convenience | 29 | 14 | 48.3 |

Exposed Through Blood

A recent large 55-hospital prospective cohort study of workers percutaneously exposed to HCV infected blood found a per exposure risk of 0.85% when the blood was also coinfected with HIV (Table 8a)(71). To estimate the probability that HIV infected blood was coinfected with HCV, we compiled prevalence studies of HCV among HIV positive persons, identifying 4 studies for a total pooled sample size of 6736 participants (Table 8b)(39, 49, 72, 73). Per 10,000 donors, the estimated risk of HCV WP infection was 4.0 (range 0.9–11.1) with ELISAand 0.4 (range 0.09–1.2) with NAT(Table 2).

Table 8.

| Table 8a: Studies of HCV Incidence in Persons Exposed through Blood or Blood Products | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Location | Population | Recruitment | # in Study |

# Infected |

Per needlestick risk |

| G.DeCarli et Al 2003 (71) | Italy | Anyone with a needlestick injury from a known HIV and HCV positive source in 55 Italian hospitals | Hospitals that voluntarily participated reported exposures and outcomes | 352 | 3 | 0.0085 |

| Table 8b: Studies of HCV Prevalence Among Persons Infected with HIV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Location | Population | Recruitment | # Tested |

# Infected | Percent Infected |

| Hall et al 2004 | San Francisco, CA | Homeless HIV positive persons | Target | 249 | 182 | 73.1 |

| Holland et al. 2000 (72) | New York City NY, Newark NJ, Baltimore MD, Washington DC, Philadelphia PA, Chicago IL, Birmingham AL, New Orleans LA, Atlanta GA, Memphis TN, Ft Lauderdale FL, Los Angeles CA | HIV infected adolescents ages 13–18 | Target | 254 | 4 | 1.6 |

| Kim et al. 2008 (73) | New York City, NY | HIV infected patients seeking care at a hospital- based HIV treatment clinic | Convenience | 5639 | 1411 | 25 |

| Bollepalli et al. 2007 (39) | Phoenix, AZ | HIV infected patients recruited from 2 urban clinics catering to patients with HIV or liver disease | Convenience | 242 | 74 | 30.1 |

Incarcerated

We were only able to identify one intra-prison incidence study of HCV incidence with a total sample size of 337 participants (Table 9)(74). Incidence was estimated to be 0.4 per 100 person-years (95% CI 0.04–1.3, Table 2). Per 10,000 donors, the estimated risk was 7.2 (range 0.7–23.5) with ELISA and 0.8 (range 0.08–2.5) with NAT.

Table 9.

Studies of HCV Incidence in Incarcerated Individuals

| Study | Location | Population | Recruitment | # in Study |

# Infected |

Person Years |

Incidence Rate (per 100 pys) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macalino et al 2004 (74) | Rhode Island | Men in jail at least 12 months | Target | 337 | 2 | 550.9 | 0.4 |

DISCUSSION

We found that the risk of HCV WP infection varied significantly across HRD behavioral categories and testing methods.Estimated WP risk of HCV per 10,000 donors ranged from 0.26–300.6based on WP for ELISA and from 0.027–32.4 based on WP for NAT. This is significantly higher than the estimated WP risk of HIV infection which ranged from 0.04–12.9 per 10,000 donors in a similarly conducted systematic review and meta-analysis(26). IDUs carried the highest risk of HCV WP infection (300.6 per 10,000 donors with ELISA and 32.4 with NAT), followed by commercial sex workers and donors engaging in high risk sexual behavior (114.9 per 10,000 donors with ELISA and 12.3 with NAT), MSMs (32.5 per 10,000 with ELISA and 3.5 with NAT), incarcerated donors (7.2 per 10,000 donors with ELISA and 0.8 with NAT), donors exposed to infected blood (4.0 per 10,000 donors with ELISA and 0.4 with NAT), and hemophiliacs (0.26 per 10,000 with ELISA and 0.027 with NAT).Relative order of risk differed somewhat from that for HIV WP infection, where IDUs also carried the highest risk of HIV WP infection but were followed by MSMs, CSWs, incarcerated donors, donors exposed to HIV through blood, donors engaging in high risk sexual behavior, and hemophiliacs. It is important to note that these estimates are only applicable to donors in the United States and Canada from which our data are drawn, and these estimates may be quite different in other parts of the world.

Previous studies have shown that the risk of sexual transmission of HCV is very low(14, 15). It is thought that the risks might increase for persons with multiple sexual partners, STIs, and HIV infection but this has not been shown definitively(16–18). Commercial sex workers, persons engaging in high risk sexual behavior, and MSMs were among the highest risk categories for HCV WP infection in our analysis. While this might be partially explained by sexual risk factors, it is possible that the higher incidence in these populations is reflective of confounding resulting from high likelihood of exhibiting other high risk behaviors, such as injection drug use, shown to result in very efficient HCV transmission.

Our study has several limitations. Incidence and prevalence studies often target higher risk individuals to ensure a sufficient number of cases to examine outcomes of interest. As such our results are not necessarily generalizable to the underlying populations, and may be overestimates of the true WP risk.Another issue is the potential for overlap between categories. While we excluded estimates in persons with multiple risk factors, most studies did not measure all HRD behaviors and as such incidence in one category might be explained not by the risk of the behavior itself but by its correlation with another risky behavior. This is especially true for commercial sex workers who have been previously shown to have high rates of injection drug use.

Our study is the first to systematically report the risk of HCV WP infection in donors meeting the PHS/CDC high risk criteria, and we found a fairly significant risk of WP infection, particularly in the IDU category. HCV-specific antibodies are typically not detectable until 2 months or longer after acquisition of infection; as such the risk of WP infection in populations is quite high when ELISA is used. NAT, with a WP of approximately 7 days, reduces the risk of WP HCV infection by an order of magnitude compared to ELISA, from approximately 3 in 100 to 3 in 1000 among IDUs. Our findings suggest that the use of these categories to identify persons at risk of HCV infection is not unreasonable as risk of HCV WP infection is very high, particularly for injection drug users. However, for some categories (hemophiliacs and persons exposed to HIV (+) blood), the risk was minimal. Furthermore, because the guidelines were not specifically developed for HCV, there may be other behavioral risk factors not included in the criteria that place a person a high risk of acquiring HCV that are not currently captured.Previous studies have suggested that tattooing, body piercing, and intranasal cocaine use might be important routes of HCV transmission (75, 76), as such these risk factors should be evaluated as potential additional categories in any future revisions of these guidelines.

In conclusion, we hope that these data, combined with those of HIV WP infection risk among patients in the same behavioral categories, will help clinical decision-making and counseling with regards to HRD organs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication was supported by Grant Number UL1 RR 025005 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. It was also supported by Grant Number R21DK089456 from the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDDK, the NIH, or the NCRR.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PHS

Public Health Service

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C Virus

- WP

Window Period

- OPO

Organ Procurement Organization

- ELISA

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- NAT

Nucleic Acid Testing

- IDU

Injection Drug User

- MSM

Men who have Sex with Men

- CSW

Commercial Sex Worker

APPENDIX

PubMed Search, Performed November 27th 2008

(

(("hiv"[MeSH Terms] AND "prevalence"[MeSH Terms]) OR

("hivseroprevalence"[MeSH Terms]) OR

("hiv"[MeSH Terms] AND "incidence"[MeSH Terms]) OR

("hiv"[MeSH Terms] AND "seroepidemiologic studies"[MeSH Terms]) OR

("hepatitis c"[MeSH Terms] AND "prevalence"[MeSH Terms]) OR

("hepatitis c"[MeSH Terms] AND "incidence"[MeSH Terms]) OR

("hepatitis c"[MeSH Terms] AND "seroepidemiologic studies"[MeSH Terms]) ) AND

("1995/01/01"[PDAT]:"2008/11/27"[PDAT]) AND

("humans"[MeSH Terms]) AND

(English[lang]) NOT

(Clinical Trial[ptyp]

Editorial[ptyp] OR Letter[ptyp] OR

Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp] OR Review[ptyp] OR

Africa[MeSH Terms] OR Asia[MeSH Terms] OR

Caribbean Region[MeSH Terms] OR

Central America[MeSH Terms] OR

Latin America[MeSH Terms] OR

South America[MeSH Terms] OR

Antarctic Regions[MeSH Terms] OR

Arctic Regions[MeSH Terms] OR

Atlantic Islands[MeSH Terms] OR

Australia[MeSH Terms] OR

Europe[MeSH Terms] OR

Historical Geographic Locations[MeSH Terms] OR

Indian Ocean Islands[MeSH Terms] OR

Oceania[MeSH Terms] OR

Pacific Islands[MeSH Terms] OR

Mexico[MeSH Terms])) OR

(

(("hiv"[tiab] AND "prevalence"[tiab]) OR

("hivseroprevalence"[tiab]) OR

("hiv"[tiab] AND "incidence"[tiab]) OR

("hepatitis c"[tiab] AND "prevalence"[tiab]) OR

("hepatitis c"[tiab] AND "seroprevalence"[tiab]) OR

("hepatitis c"[tiab] AND "incidence"[tiab]) OR

("HCV"[tiab] AND "prevalence"[tiab]) OR

("HCV"[tiab] AND "seroprevalence"[tiab]) OR

("HCV"[tiab] AND "incidence"[tiab]) ) AND

("2008/01/01"[PDAT]:"2008/11/27"[PDAT]) AND

(English[lang]) NOT

(Clinical Trial[ptyp]

Editorial[ptyp] OR Letter[ptyp] OR

Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp] OR Review[ptyp])

)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. This study was not funded in any way by a commercial organization.

Contributor Information

Lauren M. Kucirka, Email: LKucirka@jhsph.edu.

Harini Sarathy, Email: hsarathy@jhsph.edu.

Priyanka Govindan, Email: pgovind3@jhmi.edu.

Joshua H. Wolf, Email: jwolf8@jhmi.edu.

Trevor A. Ellison, Email: telliso1@jhmi.edu.

Leah J. Hart, Email: lhart13@son.jhmi.edu.

Robert A. Montgomery, Email: rmonty@jhmi.edu.

R. Lorie Ros, Email: rros@jhsph.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Provisional Public Health Service inter-agency recommendations for screening donated blood and plasma for antibody to the virus causing acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. [cited 2008 September 12];1985 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00033029.htm. [PubMed]

- 2.Rogers Martha F, MDRJS MD, Lawton Kay E, RN MN, Moseley Robin R, MAT, Jones Wanda K., DrPH [cited 2008 September 12th];Guidelines for Preventing Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Through Transplantation of Human Tissue and Organs. 1994 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/MMWR/preview/mmwrhtml/00031670.htm. [PubMed]

- 3.Kucirka LD, NN Montgomery RA, Segev DL, Singer AL. High Infectious Risk Organ Donors in Kidney Transplantation: Risks, Benefits, and Current Practices. Dialysis and Transplant. 2010;39(5):186–189. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNOS. Minimum Procurement Standards for an OPO. 2008 In. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kucirka LM, Singer AL, Ros RL, Montgomery RA, Dagher NN, Segev DL. Underutilization of hepatitis C-positive kidneys for hepatitis C-positive recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(5):1238–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn J, Cohen SM. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus through liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2008;14(11):1603–1608. doi: 10.1002/lt.21534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apperley JF, Rice SJ, Hewitt P, Rombos Y, Barbara J, Gabriel FG, et al. HIV infection due to a platelet transfusion after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Eur J Haematol. 1987;39(2):185–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1987.tb00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calabrese F, Angelini A, Cecchetto A, Valente M, Livi U, Thiene G. HIV infection in the first heart transplantation in Italy: fatal outcome. Case report. APMIS. 1998;106(4):470–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humar A, Morris M, Blumberg E, Freeman R, Preiksaitis J, Kiberd B, et al. Nucleic acid testing (NAT) of organ donors: is the 'best' test the right test? A consensus conference report. Am J Transplant. 10(4):889–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanzi E, Romano L, Zanetti AR. Hepatitis type C: modes of transmission and preventive measures. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995;(13 Suppl 13):S13–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baggaley RF, Boily MC, White RG, Alary M. Risk of HIV-1 transmission for parenteral exposure and blood transfusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2006;20(6):805–812. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218543.46963.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dosekun O, Fox J. An overview of the relative risks of different sexual behaviours on HIV transmission. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 5(4):291–297. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a88a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tohme RA, Holmberg SD. Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission? Hepatology. doi: 10.1002/hep.23808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandelli C, Renzo F, Romano L, Tisminetzky S, De Palma M, Stroffolini T, et al. Lack of evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among monogamous couples: results of a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(5):855–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marincovich B, Castilla J, del Romero J, Garcia S, Hernando V, Raposo M, et al. Absence of hepatitis C virus transmission in a prospective cohort of heterosexual serodiscordant couples. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(2):160–162. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mele A, Tosti ME, Marzolini A, Moiraghi A, Ragni P, Gallo G, et al. Prevention of hepatitis C in Italy: lessons from surveillance of type-specific acute viral hepatitis. SEIEVA collaborating Group. J Viral Hepat. 2000;7(1):30–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2000.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman JG, Minkoff H, Landesman S, Dehovitz J. Heterosexual transmission of hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and HIV-1 in a sample of inner city women. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27(6):338–342. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200007000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stroffolini T, Lorenzoni U, Menniti-Ippolito F, Infantolino D, Chiaramonte M. Hepatitis C virus infection in spouses: sexual transmission or common exposure to the same risk factors? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(11):3138–3141. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busch MP, Lee LL, Satten GA, Henrard DR, Farzadegan H, Nelson KE, et al. Time course of detection of viral and serologic markers preceding human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconversion: implications for screening of blood and tissue donors. Transfusion. 1995;35(2):91–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35295125745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rehermann B. Hepatitis C virus versus innate and adaptive immune responses: a tale of coevolution and coexistence. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(7):1745–1754. doi: 10.1172/JCI39133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer AL, Kucirka LM, Namuyinga RHC, Subramanian AK, Segev DL. The high risk donor: viral infections in solid organ transplantation. Current Opinion in Organ Transplantation. 2008;13:400–404. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283094ba3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. [cited 2008 September 12];Minimum Procurement Standards for an Organ Procurment Organization. 2008 Available from: http://www.unos.org/PoliciesandBylaws2/policies/pdfs/policy_2.pdf.

- 23.Kucirka LM, Alexander C, Namuyinga R, Hanrahan C, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Viral Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) and OPO-Level Disposition of High-Risk Donor Organs. Am J Transplant. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borst A, Box AT, Fluit AC. False-positive results and contamination in nucleic acid amplification assays: suggestions for a prevent and destroy strategy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23(4):289–299. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Botte C, Janot C. Epidemiology of HCV infection in the general population and in blood transfusion. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;(11 Suppl 4):19–21. doi: 10.1093/ndt/11.supp4.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kucirka LM, Sarathy H, Govindan P, Wolf JH, Ellison TA, Hart LJ, Montgomery RASD. Risk of Window Period HIV Infection in High Risk Donors: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Transplant. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03329.x. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzeo C, Azzaroli F, Giovanelli S, Dormi A, Festi D, Colecchia A, et al. Ten year incidence of HCV infection in northern Italy and frequency of spontaneous viral clearance. Gut. 2003;52(7):1030–1034. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou S, Dodd RY, Stramer SL, Strong DM. Probability of viremia with HBV, HCV, HIV, and HTLV among tissue donors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(8):751–759. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Germain M, Goldman M. Blood donor selection and screening: strategies to reduce recipient risk. Am J Ther. 2002;9(5):406–410. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen DE, Russell CJ, Golub SA, Mayer KH. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among men who have sex with men at a Boston community health center and its association with markers of high-risk behavior. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(8):557–564. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dominitz JA, Boyko EJ, Koepsell TD, Heagerty PJ, Maynard C, Sporleder JL, et al. Elevated prevalence of hepatitis C infection in users of United States veterans medical centers. Hepatology. 2005;41(1):88–96. doi: 10.1002/hep.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammer GP, Kellogg TA, McFarland WC, Wong E, Louie B, Williams I, et al. Low incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among sexually active non-intravenous drug-using adults, San Francisco, 1997–2000. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(12):919–924. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000091152.31366.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang LY, Kramer JR, Troisi C, Bull L, Grimes CZ, Lyerla R, et al. Relationship of cosmetic procedures and drug use to hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus infections in a low-risk population. Hepatology. 2006;44(2):341–351. doi: 10.1002/hep.21252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Butterfield MI, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31–37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Boivin JF, Cedras L, Vincelette J. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among street youths. CMAJ. 2001;165(5):557–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amon JJ, Garfein RS, Ahdieh-Grant L, Armstrong GL, Ouellet LJ, Latka MH, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users in the United States, 1994–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(12):1852–1858. doi: 10.1086/588297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):705–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baumbach JP, Foster LN, Mueller M, Cruz MF, Arbona S, Melville S, et al. Seroprevalence of select bloodborne pathogens and associated risk behaviors among injection drug users in the Paso del Norte region of the United States-Mexico border. Harm Reduct J. 2008;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bollepalli S, Mathieson K, Bay C, Hillier A, Post J, Van Thiel DH, et al. Prevalence of risk factors for hepatitis C virus in HIV-infected and HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(6):367–370. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000240295.35457.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briggs ME, Baker C, Hall R, Gaziano JM, Gagnon D, Bzowej N, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection at an urban Veterans Administration medical center. Hepatology. 2001;34(6):1200–1205. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.29303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brillman JC, Crandall CS, Florence CS, Jacobs JL. Prevalence and risk factors associated with hepatitis C in ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(5):476–480. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.32642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choy Y, Gittens-Williams L, Apuzzio J, Skurnick J, Zollicoffer C, McGovern PG. Risk factors for hepatitis C infection among sexually transmitted disease-infected, inner city obstetric patients. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2003;11(4):191–198. doi: 10.1080/10647440300025520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Des Jarlais DC, Diaz T, Perlis T, Vlahov D, Maslow C, Latka M, et al. Variability in the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus infection among young injecting drug users in New York City. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(5):467–471. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Firestone Cruz M, Fischer B, Patra J, Kalousek K, Newton-Taylor B, Rehm J, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of hepatitis C infection (HCV) in a multi-site Canadian population of illicit opioid and other drug users (OPICAN) Can J Public Health. 2007;98(2):130–133. doi: 10.1007/BF03404324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fuller CM, Ompad DC, Galea S, Wu Y, Koblin B, Vlahov D. Hepatitis C incidence--a comparison between injection and noninjection drug users in New York City. J Urban Health. 2004;81(1):20–24. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gunn RA, Murray PJ, Ackers ML, Hardison WG, Margolis HS. Screening for chronic hepatitis B and C virus infections in an urban sexually transmitted disease clinic: rationale for integrating services. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(3):166–170. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagan H, Thiede H, Des Jarlais DC. Hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users: survival analysis of time to seroconversion. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):543–549. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000135170.54913.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Ford J, Paciorek A, Lum PJ. Traveling young injection drug users at high risk for acquisition and transmission of viral infections. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93(1–2):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hall CS, Charlebois ED, Hahn JA, Moss AR, Bangsberg DR. Hepatitis C virus infection in San Francisco's HIV-infected urban poor. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neaigus A, Gyarmathy VA, Miller M, Frajzyngier V, Zhao M, Friedman SR, et al. Injecting and sexual risk correlates of HBV and HCV seroprevalence among new drug injectors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89(2–3):234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Page-Shafer KA, Cahoon-Young B, Klausner JD, Morrow S, Molitor F, Ruiz J, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in young, low-income women: the role of sexually transmitted infection as a potential cofactor for HCV infection. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):670–676. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patrick DM, Tyndall MW, Cornelisse PG, Li K, Sherlock CH, Rekart ML, et al. Incidence of hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users during an outbreak of HIV infection. CMAJ. 2001;165(7):889–895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rifai MA, Moles JK, Lehman LP, Van der Linden BJ. Hepatitis C screening and treatment outcomes in patients with substance use/dependence disorders. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(2):112–121. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roy E, Alary M, Morissette C, Leclerc P, Boudreau JF, Parent R, et al. High hepatitis C virus prevalence and incidence among Canadian intravenous drug users. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(1):23–27. doi: 10.1258/095646207779949880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sandhu J, Preiksaitis JK, Campbell PM, Carriere KC, Hessel PA. Hepatitis C prevalence and risk factors in the northern Alberta dialysis population. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(1):58–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shannon K, Rusch M, Morgan R, Oleson M, Kerr T, Tyndall MW. HIV and HCV prevalence and gender-specific risk profiles of crack cocaine smokers and dual users of injection drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43(3–4):521–534. doi: 10.1080/10826080701772355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sivapalasingam S, Malak SF, Sullivan JF, Lorch J, Sepkowitz KA. High prevalence of hepatitis C infection among patients receiving hemodialysis at an urban dialysis center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23(6):319–324. doi: 10.1086/502058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spittal PM, Craib KJ, Teegee M, Baylis C, Christian WM, Moniruzzaman AK, et al. The Cedar project: prevalence and correlates of HIV infection among young Aboriginal people who use drugs in two Canadian cities. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(3):226–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strasfeld L, Lo Y, Netski D, Thomas DL, Klein RS. The association of hepatitis C prevalence, activity, and genotype with HIV infection in a cohort of New York City drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(3):356–364. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200307010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tabibian JH, Wirshing DA, Pierre JM, Guzik LH, Kisicki MD, Danovitch I, et al. Hepatitis B and C among veterans on a psychiatric ward. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(6):1693–1698. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thorpe LE, Ouellet LJ, Levy JR, Williams IT, Monterroso ER. Hepatitis C virus infection: prevalence, risk factors, and prevention opportunities among young injection drug users in Chicago, 1997–1999. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(6):1588–1594. doi: 10.1086/317607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tortu S, Neaigus A, McMahon J, Hagen D. Hepatitis C among noninjecting drug users: a report. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36(4):523–534. doi: 10.1081/ja-100102640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weisbord JS, Trepka MJ, Zhang G, Smith IP, Brewer T. Prevalence of and risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among STD clinic clientele in Miami, Florida. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(1):E1. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wylie JL, Shah L, Jolly AM. Demographic, risk behaviour and personal network variables associated with prevalent hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and HIV infection in injection drug users in Winnipeg, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:229. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zule WA, Bobashev G. High dead-space syringes and the risk of HIV and HCV infection among injecting drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100(3):204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Augenbraun M, Goedert JJ, Thomas D, Feldman J, Seaberg EC, French AL, et al. Incident hepatitis C virus in women with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(10):1357–1364. doi: 10.1086/379075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Lum PJ, Bourgois P, Stein E, Evans JL, et al. Hepatitis C virus seroconversion among young injection drug users: relationships and risks. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(11):1558–1564. doi: 10.1086/345554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thorpe LE, Ouellet LJ, Hershow R, Bailey SL, Williams IT, Williamson J, et al. Risk of hepatitis C virus infection among young adult injection drug users who share injection equipment. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(7):645–653. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.7.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dodd RY, Notari EPt, Stramer SL. Current prevalence and incidence of infectious disease markers and estimated window-period risk in the American Red Cross blood donor population. Transfusion. 2002;42(8):975–979. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O'Brien SF, Yi QL, Fan W, Scalia V, Kleinman SH, Vamvakas EC. Current incidence and estimated residual risk of transfusion-transmitted infections in donations made to Canadian Blood Services. Transfusion. 2007;47(2):316–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Carli G, Puro V, Ippolito G. Risk of hepatitis C virus transmission following percutaneous exposure in healthcare workers. Infection. 2003;(31 Suppl 2):22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Holland CA, Ma Y, Moscicki B, Durako SJ, Levin L, Wilson CM. Seroprevalence and risk factors of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human cytomegalovirus among HIV-infected and high-risk uninfected adolescents: findings of the REACH Study. Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27(5):296–303. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200005000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim JH, Psevdos G, Suh J, Sharp VL. Co-infection of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in New York City, United States. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(43):6689–6693. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Macalino GE, Vlahov D, Sanford-Colby S, Patel S, Sabin K, Salas C, et al. Prevalence and incidence of HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus infections among males in Rhode Island prisons. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1218–1223. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Conry-Cantilena C, VanRaden M, Gibble J, Melpolder J, Shakil AO, Viladomiu L, et al. Routes of infection, viremia, and liver disease in blood donors found to have hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(26):1691–1696. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606273342602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haley RW, Fischer RP. Commercial tattooing as a potentially important source of hepatitis C infection. Clinical epidemiology of 626 consecutive patients unaware of their hepatitis C serologic status. Medicine (Baltimore) 2001;80(2):134–151. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]