Abstract

Problem

Current methods of contraception lack specificity and are accompanied with serious side effects. A more specific method of contraception is needed. Contraceptive vaccines can provide most, if not all, the desired characteristics of an ideal contraceptive.

Approach

This article reviews several factors involved in the establishment of pregnancy, focusing on those that are essential for successful implantation. Factors that are both essential and pregnancy-specific can provide potential targets for contraception.

Conclusion

Using database search, 76 factors (cytokines/chemokines/growth factors/others) were identified that are involved in various steps of the establishment of pregnancy. Among these factors, three, namely chorionic gonadotropin (CG), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), and preimplantation factor (PIF), are found to be unique and exciting molecules. Human CG is a well-known pregnancy-specific protein that has undergone phase I and phase II clinical trials, in women, as a contraceptive vaccine with encouraging results. LIF and PIF are pregnancy-specific and essential for successful implantation. These molecules are intriguing and may provide viable targets for immunocontraception. A multiepitope vaccine combining factors/antigens involved in various steps of the fertilization cascade and pregnancy establishment, may provide a highly immunogenic and efficacious modality for contraception in humans.

Keywords: Contraceptive vaccine, pregnancy-specific factors, implantation, immunocontraception

Introduction

With the continually increasing world population, there is an urgent need for an alternative form of contraception. Currently, available methods, including most used modalities, namely steroid contraceptives and intrauterine devices, haveseveral serious side effects. A more targeted, less invasive approach to contraception is desired. Contraceptive vaccines (CV) would provide an ideal alternative. CV would be easy to administer, less expensive, readily available, and more importantly, would be specific. By targeting factors that are essential for establishment of pregnancy, a CV would block the action of a factor(s) and prevent the onset of pregnancy. One of the essential factors that has been extensively studied is the chorionicgonadotropin (CG). Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is a major systemic regulator of embryo development, implantation and is secreted by the implanting trophoblast,1 making it an ideal pregnancy-specific target for CV development. Several forms of hCG vaccines have undergone clinical trialsin women, both phase I and phase II, displaying positive contraceptive effects.2, 3 While the outlook of the hCG vaccine looks promising, research on additional potential targets continue with an ultimate goal of finding a vaccine that is more immunogenic and efficacious. This article will review the additional factors that are involved in the development and implantation of the embryo, with a focus on those that have been shown to be essential for normal embryonic development and/or implantation and pregnancy-specific. The long-term goal is to target these molecules for the development of highly specific, non-steroidal, and efficacious vaccine for birth control.

Discussion

1. Factors Involved in Various Stages of Establishment of Pregnancy

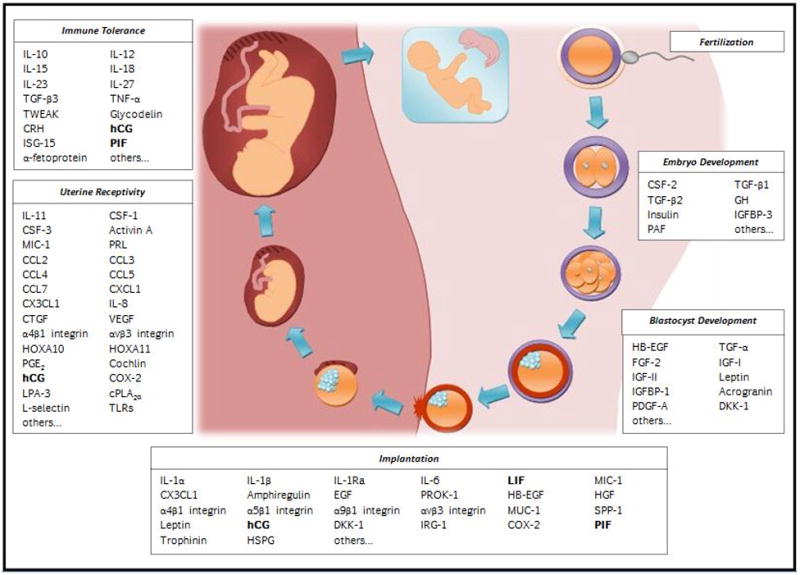

The PubMed database (www.pubmed.gov) was searched using the following keywords: secreted/pregnancy/fertilization/implantation/embryo development/pregnancy-specific/molecules. Further focus was placed on those articles that were relevant to murine or human implantation and pregnancy. The search identified 76 cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, integrins, and miscellaneous factors involved in the establishment of pregnancy. Their molecular and functional parameters are summarized in Tables I–III. These 76 factors are grouped into five categories depending upon which stage of pregnancy establishment they are primarily involved in and described below(Fig 1).

Table I.

Cytokines Involved in the Establishment of Pregnancy

| Protein | Size | Human Gene | Role | Species | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interleukins | IL-1α | 18 kDa | IL1A | induces changes for adhesion and invasion 44, 45 | human/mouse |

| IL-1β | 17.5 kDa | IL1B | induces changes for adhesion and stimulates IL-8 production 43, 44, 46 | human/mouse | |

| IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) | 17 kDa | lL1RN | prevents adhesion 47 | mouse | |

| IL-6 | 26 kDa | IL6 | stimulates leptin secretion and metalloproteinase activity 74 | human/mouse | |

| IL-10 | 18 kDa | IL10 | decreases cytotoxic activation of uNK cells 107 | human/mouse | |

| IL-11 | 23 kDa | IL11 | receptor signaling required for decidua development 71–73 | human/mouse | |

| IL-12 | 75 kDa | IL12A/IL12B | Immunomodulatory 104 | human | |

| IL-15 | 18 kDa | IL15 | regulates IL-8 expression and uNK cells 85 | human | |

| IL-18 | 18 kDa | IL18 | increases perforin expression and cytolytic potentials of uNK cells 105 | human | |

| IL-23 | 21 kDa | IL23A/IL12B | immunomodulatory, regulates IL-8 expression 99, 108 | human/mouse | |

| IL-27 | 27 kDa | EBI3/IL30 | Immunomodulatory 108 | mouse | |

| leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) | 26 kDa | LIF | regulates expression of genes important in implantation 19, 20 | human/mouse | |

| CSFs | Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) | ~19 kDa | CSF3 | recruits macrophages to the uterus to prepare it for implantation 90 | mouse |

| Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) | 14.4 kDa | CSF2 | enhances proliferation and viability of blastomeres 14, 15 | mouse | |

| Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) | ~36 kDa | CSF1 | recruits macrophages to the uterus to prepare it for implantation 89, 90 | mouse | |

| TGFβ Superfamily | Activin A | 24–28 kDa | INHBA | promotes decidualization; prevents activitation of T cells 68–70 | mouse |

| Macrophage inhibitory cytokine (MIC-1) | 25 kDa | GDF15 | regulates trophoblast migration/invasion and decidualization 39, 85 | human | |

| Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) | 25 kDa | TGFB1 | regulate embryo development 12, 13 | human/mouse | |

| Transforming growth factor β2 (TGFβ2) | 25 kDa | TGFB2 | regulate embryo development 12 | human | |

| Transforming growth factor β3 (TGFβ3) | 25 kDa | TGFB3 | promotes a regulatory T cell response 111 | mouse | |

| TNF Family | Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) | 25 kDa | TNF | immunomodulatory, has deleterious effects at high levels 4–6 | human/mouse |

| tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis(TWEAK) | 17 kDa | TWEAK | controls cytotoxicity, possibly through regulation of IL-15 and IL-18 108, 113 | human/mouse | |

| Hormones | Growth hormone (GH) | 22 kDa | GH1/GH2 | effects quality of embryo and fertilization rate 17 | human |

| Prolactin (PRL) | 24 kDa | PRL | promotes decidualization 76 | human/mouse |

Table III.

Integrins and Other Factors Involved in the Establishment of Pregnancy

| Protein | Size | Human Gene | Role | Species | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrins | α4β1 integrin | ~280 kDa | ITGA4/ITGB1 | important in implantation and decidualization 55 | human |

| α5β1 integrin | ~265 kDa | ITGA5/ITGB1 | essential for the migration of extravillous trophoblasts (IFG-I-induced) 37 | human | |

| α9β1 integrin | ~230 kDa | ITGA9/ITGB1 | important in implantation 26 | human | |

| αvβ3 integrin | ~230 kDa | ITGAV/ITGB3 | involved in EVT migration (IGF-I-induced), important in implantation and decidualization 18, 38, 55 | human | |

| Other Factors | Adrenomedullin | 6 kDa | ADM | involved in invasion and pinopode formation 62–64 | human/mouse |

| α-fetoprotein | 70 kDa | AFP | inhibits the immune response 118 | mouse | |

| Cochlin (COCH) | ~60 kDa | COCH | regulated by LIF; marker for uterine receptivity? 21 | mouse | |

| Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) | ~5 kDa | CRH | promotes implantation by regulating FasL expression 114, 115 | human/mouse | |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) | 72 kDa | PTGS2 | synthesizes prostaglandins; required for fertilization, implantation and decidualization 79 | mouse | |

| Cytosolic phospholipase A2α (cPLA2α) | 85 kDa | cPLA2α | provides arachidonic acid for synthesis of PGs by COX2; deficiency results in abnormal spacing and delayed implantation 60 | mouse | |

| Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) | ~25 kDa | DKK1 | required for blastocyst outgrowth and adhesion 33 | mouse | |

| Glycodelin | 28 kDa | PAEP | involved in sperm-oocyte binding and prevention of the inflammatory response 109, 110, 124 | human | |

| Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) | >500kDa | n/a | Expressed on the trophectoderm of blastocyst during the attachment phase of implantation 54 | mouse | |

| Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) | 37.6 kDa | CGB | responsible for progesterone production and LIF expression; maintains the corpus luteum; also involved in angiogenesis, attachment and immune tolerance 1, 77, 116 | human | |

| Homebox A10 (HOXA-10) | ~40 kDa | HOXA10 | required for decidualization and successful implantation 82–84 | human/mouse | |

| Homebox A11 (HOXA-11) | ~35 kDa | HOXA11 | required foruterine stromal and glandular cell differentiation 81 | mouse | |

| Immunoresponsive gene 1 homolog (IRG1) | ~52 kDa | IRG1 | regulated by progesterone and LIF; important for implantation 19, 42 | mouse | |

| Insulin | 5.8 kDa | INS | increases cell proliferation of early stage embryos 7, 8 | mouse | |

| Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) | 7.65 kDa | IGF1 | increases number of cells in inner cell mass 31 | mouse | |

| Insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) | 7.5 kDa | IGF2 | involved in oocyte maturation and development of the embryo to blastocyst stage 9, 16 | human/mouse | |

| Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 (IGFBP-1) | ~25 kDa | IGFBP1 | limits trophoblast growth and inhibits IGF-I activity 26, 66 | human | |

| Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2(IGFBP-3) | ~40 kDa | IGFBP3 | upregulated by LIF; involved in oocyte maturation and embryo development 9, 19 | human/mouse | |

| Interferon-induced 17 kDa protein (ISG15) | 17 kDa | ISG15 | induced in the endometrium in response to the implanting conceptus; immunomodulatory? 117 | human/mouse | |

| Leptin | 16 kDa | LEP | involved in blastocyst development; mediates the invasiveness of the cytotrophoblast 32, 45, 65 | human/mouse | |

| Lysophosphatidic acid receptor 3 (LPA3) | 40 kDa | LPAR3 | regulates uterine receptivity 58, 59 | mouse | |

| L-selectin | 43 kDa | SELL | plays an early role in the homing of leukocytes the uterus, regulating uterine receptivity 102, 103 | human/mouse | |

| Mucin 1 (MUC-1) | >300 kDa | MUC1 | involved in embyro attachment 1, 53 | mouse/human | |

| Oviduct-specific glycoprotein (OVGP1; MUC-9) | 120 kDa | OVGP1 | enhances binding of sperm to the zona pellucida 123 | human | |

| Platelet activating factor (PAF) | ~524 kDa | n/a | stimulates early embryo development 10, 11 | human/mouse | |

| Preimplantation factor (PIF) | 0.6–1.8 kDa | n/a | regulates immunity, promotes adhesion and invasion, and regulates apoptotic processes56, 57 | human | |

| Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) | 352 kDa | n/a | involved in the inflammatory response in the endometrium required for implantation 1 | human | |

| Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1) | 44 kDa | SPP1 | allows for attachment to the luminal epithelium; induces focal adhesions 49, 50 | mouse | |

| Trophinin | 69 kDa | TRO | involved in activation of the trophectoderm for adhesion 51 | human/mouse |

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the factors involved in the establishment of pregnancy. Factors that are essential and pregnancy-specific are represented in bold. These factors may provide interesting targets for contraception.

a. FactorsInvolved inEarlyEmbryonicDevelopment

After fertilization, the resultant zygote undergoes a series of divisions and modifications before progressing to the blastocyst stage. Several factors promote growth and proliferation of these early embryos. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) has been shown to bind early mouse embryos and may promote embryonic development,4 however, it has deleterious effects at high levels.5, 6 Insulin has been shown to stimulate DNA, RNA, protein synthesis,7 and increase the rate at which these cells proliferate during the early diploid and tetraploid stages.8 Higher levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) have been correlated to the increased embryonic development.9 The embryo secretes platelet activating factor (PAF) that promotes embryo development.10 Blocking the action of PAF with an antagonist prevents implantation.11 Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 plays an important role in the development of the blastocyst.12 TGF-β1 null mice produce embryos that are arrested at the morula stage, not developing to a blastocyst.13 Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CDF) enhances the viability and proliferation of blastomeres in early embryos.14, 15 Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-II also promotes the progression to the blastocyst stage. IGF-II antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) decreasethe rate that embryos enterintothe blastocyst stage.16 Another factor affecting the growth and development of early embryos is growth hormone (GH). Patients with in vitro fertilization (IVF) failures have been shown to have GH deficiency. Supplementation with GH improves embryo quality and fertilization ratesin these patients.17

b. Factors Affecting Development ofBlastocyst

Once the blastocyst has formed, it must undergo changes that allow for implantation. A few key systemic factors regulate this process. LIF is an essential factor whose expression is under the control of progesterone. LIF controls the expression of several implantation-related genes, such as heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF), amphiregulin, epiregulin, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3), immunoresponsive gene 1 homolog (IRG-1), and cochlin. 18–21 Gene knockout and LIF antagonist studies in mice have shown that deleting the LIF/LIF receptor gene or impeding the interaction of LIF with the receptor results in implantation failure.22, 23 HB-EGF promotes the development of blastocysts through the hatching stage as well as the motility and attachment of the blastocyst.24

Several growth factors influence the growth and development of blastocyst. These include TGF-α, basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2),25 hepatocyte growth factor(HGF),26 platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFA),27 and acrogranin. TGF-α has been demonstrated to stimulate DNA and protein synthesis in blastocysts as well asincrease the rate of blastocoel expansion. Administration of TGF-α antisense ODN significantly reduces the rate of blastocoel expansion.28 Rate of blastocoel expansion is shown to increase in the presence of acrogranin. Not only does it affect expansion, it also promotes blastocyst hatching and outgrowth. Anti-acrogranin antibodies reduce these effects in vitro and also prevent the 8-cell embryos to develop to blastocysts.29, 30 The inner cell mass (ICM) continually increases in cell number as the blastocyst develops. IGF-I, IGF-II, and leptin have all been reported to increase the number of ICM in cultured blastocysts.16, 31, 32 In order for the blastocyst to adhere to the uterus, it must first become activated. The outgrowth and adhesion of blastocysts is inhibited by the addition of Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1)antisense ODN, suggesting an important role for DKK-1 in blastocyst activation.33

c. Factors Impacting Implantation

Migration of the blastocyst to the implantation site is controlled by many factors. Several chemokines, including CCL-4 and CX3CL-1, promote blastocyst migration.34 Extravillous trophoblast (EVT) migration is also induced by a handful of growth factors. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) can stimulate trophoblast migration35 using the PI3K/AKT and MAP kinase signaling pathways.36 Along with EGF, IGF-I can also induce EVT migration. The α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins have been shown to play essential roles in this pathway.37, 38 FGF-2 may also play a role in preparing the blastocyst for migration.25 Several factors, such as macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1 (MIC-1),39 can act to regulate the migration.

Once at the site of implantation, the blastocyst attaches to the uterine epithelium. Prokineticin 1 (PROK-1) promotes the gene expression of many implantation related genes, such as cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), LIF, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and IL-11, that allow for attachment to the uterus.40, 41 LIF, along with progesterone, lead to the upregulation of IRG-1.19 Antisense ODN leads to suppression of IRG-1 expression, resulting in impairment of embryo implantation.42 Members of IL-1 family of cytokines are important in adhesion of blastocyst. IL-1β stimulates IL-8 production that is necessary for implantation.43 IL-1α and IL-1β secreted by the embryo mediate pathways involving integrins. Both of these growth factors appear to target endometrial epithelial β3 integrin, preparing the blastocyst for adhesion.44 IL-1α upregulates integrin expression and induces changes that result in a more invasive phenotype.45 Both IL-1α and IL-1β have been detected in the sera of women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) having higher implantation rates, suggesting that they may have an important role.46 IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) inhibits the actions of IL-1α and IL-1β by down-regulating integrins.47 CX3CL-1 regulates the expression of adhesion molecules, such as secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), that mediate attachment of the implanting blastocyst.48 SPP1 co-localizes with leukocytes and macrophages and may allow for attachment to the luminal epithelium through SPP1-positive macrophages.49 In the ovine model, SPP1 was demonstrated to bind integrins (αvβ3 and α5β1) on the conceptus and luminal epithelium.50 Along with integrins, trophinin is involved in blastocyst binding to the uterine epithelium.51 Acrogranin and DKK-1 are both essential adhesion factors. The inhibition or removal of these factors reduces adhesion.30, 33 Other factors involved in attachment are mucin-1 (MUC-1),52, 53 heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), 54, 55 and PIF. PIF is an embryo-derived peptide playing an essential role in adhesion.56, 57

As the blastocyst attaches, various molecules participate in the timing and spacing of the embryo, at least in the murine model. Lysophosphatidic acid 3 (LPA3) and cytosolic phospholipase A2α (cPLA2α) regulate embryo spacing. Mice deficient in either of these molecules have delayed implantation and abnormal spacing of embryos, resulting in smaller litter size, and, in some cases, pregnancy failure.58–60 HB-EGF-deficient micealso display delayed implantation.61

Invasion of the blastocyst upon adhesion to the uterus involves various factors. Adrenomedullin enhances invasion of trophoblasts in vitro.62 Mice with reduced expression of adrenomedullin also demonstrate reduced fertility and defectin invasion.63, 64 Other factors mediating invasiveness are HGF, leptin and IGFBP-1. Both HGF and leptin induce cytotrophoblast modifications that regulate invasiveness.26, 45, 65 IGFBP-1 acts to inhibit IGF-I activity, preventing invasion.66

d. Factors Involving in Uterine Receptivity and Decidualization

Maintenance of corpus luteum (CL) is important for establishing and maintaining pregnancy. Factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)67 and hCG1 both participate in CL maintenance. CL secretes several hormones that allow for the establishment of pregnancy. Most importantly, it secretes progesterone that allows for the decidualization of the endometirum. Activin A is also secreted by the CL, promoting decidualization by preventing T cell activation,68 upregulating MMPs,69 and secreting IL-11.70 IL-11 signaling through binding to its receptor is required for the development of decidua.71, 72 IL-11 receptor null mice have defective decidualization and, as a result, are infertile.73 IL-6 also promotes implantation and decidualization by stimulating leptin secretion and MMP activity.74 IL-6-deficient mice show a decreasein viable implantation sites resulting in reduced fertility.75 Another important regulator of decidualization is prolactin (PRL). Mice lacking the PRL receptor exhibit implantation failures.76 hCG is responsible for the expression or upregulation of many factors that participate in the implantation process. Not only does hCG induce expression of two important implantation factors, LIF and IL-6,77 it also induces expression of COX-2.78 The COX-2 biosynthesizes prostaglandins, like prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which affect uterine receptivity. Inhibition of COX-2 results in inhibition of stromal cell expression, leading to decidualization failure.79, 80 Homebox (HOX)A proteins, HOXA10 and HOXA11, are involved in stromal cell differentiation required for decidualization.81–83 Mice expressing HOXA10 mutants show stromal cell and decidualization defects that result in implantation failure.82, 84 A few integrins, α4β1 and αvβ3, have also been implicated in having a role in decidualization.55 Other factors that present possible roles in regulation of decidualization include MIC-185 and connective tissue growth factor(CTGF).86–88

Leukocytes are recruited to help prepare the uterus for implantation. Many cytokines and chemokines are involved in the initiation of this essential inflammatory response. Colony stimulating factor (CSF)-1, CSF-2, and CSF-3 all serve as chemoattractants in the recruitment of macrophages to the uterus.89, 90 Homozygous crosses of mice lacking CSF-1 result in infertility.91 Upregulation of IL-8, CCL-2, and RANTES by progesterone has been demonstrated in vitro.92 CCL2 recruits macrophages, monocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and T-cells in the endometrium.89, 93–95 CCL3, CCL4, CCL5 (RANTES), and CCL7 are also involved in the recruitment of macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells.85, 89, 94, 96 IL-8 upregulates several inflammatory response genes.97, 98 Stimulation of stromal cells in vitro with IL-23 shows an increase in IL-8 expression.99 Another chemokine responsible for upregulating the inflammatory response is CXCL1. 94, 100 Recent research suggests that this inflammatory environment is mediated by the trophoblast through toll-like receptors (TLRs).101 Other factors involved in the inflammatory response are PGE21 and L-selectin. 102, 103

e. Immunomodulatory Regulators

Possibly the most critical aspect of successful pregnancy is maternal tolerance of the implanting embryo. Several cytokines act to suppress an immune response to the blastocyst. The IL-12/IL-18 system is important in managing immune responses. Alterations to the IL-12 or IL-18 levels have been associated with recurrent implantation failure.104 IL-18 has the ability to increase perforin expression and cytolytic potentials of uterine NK (uNK) cells105 and its absence or overexpression can lead to implantation failure. 106 IL-15, on the other hand, is thought to regulate uNK cells.85 Essential interleukins mediating maternal tolerance are IL-10 and IL-27. Mice lacking IL-10 exhibit fetal resorption due to an increased activation of cytotoxic uNK cells.107 Neutralization of IL-27 in mice also results in increased fetal resorption.108 Glycodelin is a pregnancy-specific protein shown to increase IL-10 production and reduce the expression of costimulatory molecules in monocyte-derived dendritic cells, suggesting a role in preventing an immune response.109, 110 TNFα is known to cause spontaneous abortion in mice and women.5, 6, 111, 112 Tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) is thought to protect against the deleterious effect of TNFα, by controlling uNK cell cytotoxicity and regulating of IL-15 and IL-18.108, 113 TNFα and interferon γ(IFNγ) cause spontaneous abortion by binding to their receptors, which are expressed in the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). An in vivo model of spontaneous abortion has been created in mice by injecting mated mice with LPS. Addition of TGF-β3 to this model increased the success of pregnancy by promoting a regulatory T-cell response.111 Studies have implicated corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) in the regulation of the immune response through killing of activated T-cells. Administration of CRH antibodies on day 3–8 of pregnancy results in implantation failure in 60% of cases.114 A CRH receptor antagonist, antalarmin, also decreases implantation and live embryos as well as FasL expression, suggesting its role in T-cell regulation.115 Other notable factors involved in immune tolerance are hCG,116 PIF,57 interferon-stimulated 17 kDa protein (ISG-15),117 and α-fetoprotein.118

2. Immunocontraceptive Targets

The purpose of this article is to review the factors that are involved in the establishment of pregnancy and delineate which of these factors are essential and pregnancy-specific. By selecting the proteins that are essential and pregnancy-specific, it is ensured that targeting these molecules will reduce fertility without affecting any other molecule and process. Research in this area has been rapidly progressing over the past decade. The pregnancy-specific protein, hCG, was initially used for detection of pregnancy in women. Now, it is being investigated as a contraceptive target for development of a birth control vaccine. Several vaccines based on the βsubunit of hCG incorporating various carriers and adjuvants have undergone phase I and phase II clinical trialsin women. A study completed in 1994 by Talwar et al recorded that women administered an hCG vaccine developed antibody titers that prevented pregnancy. Only 1 pregnancy occurred in over 1224 cycles observed in these vaccinated women.2 Another trial demonstrated that an HSD-hCG vaccine was reversible and that titers below the protective threshold showed no teratogenic effect on pregnancy outcome.3

A more recent protein of interest is LIF. Studies done in the mouse model have shown that hindering the interaction of LIF with its receptor will block implantation. Stewart et al mutated the LIF gene to express a truncated, non-functional LIF mutant. The mutated DNA was injected into blastocysts, and crossed the resulting F1 offsprings to create homozygous LIF-mutant mice. These mice demonstrated complete implantation failure.22 Administration of a LIF antagonist conjugated to polyethylene glycol (PEG-LA), increased blocking implantation in mice.23 More importantly, LIF is required for implantation not only in mice, but also in humans. LIF mRNA concentration peaks in human endometrium at the time of implantation.119 Studies on endometrial explants from fertile and infertile women reveal that LIF production in cultures from infertile women and fertile women, using intrauterine devices (IUD), was significantly less than that of cultures from normally cycling fertile women.120 A similar study showed immunostaining of LIF in biopsies from fertile women, was higher than that of infertile women.121 Recently, it was discovered that LIF gene mutations in infertile women may account for poor IVF outcome, since maternal LIF expression is critical for implantation and successful pregnancy.122 Our laboratory recently conducted a study using a vaccine targeting LIF and its receptors in the mouse model. Preliminary results are very exciting. The administration of the vaccine to female mice developed specific antibodies resulting in a reduction of fertility in the vaccinated female mice (Lemons and Naz, unpublished data).

Other interesting molecules include glycodelin,102 oviduct-specific glycoprotein 1 (OVGP-1),103, 123 trophinin and PIF. Glycodelin A has been shown to have immunosuppressive effects against the maternal response to spermatozoa.109, 110, 124 Trophinin promotes activation of blastocyst for adhesion to uterine epithelium.51 Trophinin is expressed by both trophoblast and endometrial epithelial cells and its expression seems to be regulated by hCG secretion.125 PIF is an embryo-derived peptide detected in the serum just before implantation.1 It has recently been shown to be essential for implantation by promoting adhesion, regulating immunity, and apoptosis.56, 57

3. Conclusions

The database review identified 76 various factors that are involved in several steps of establishment of pregnancy. At least three of these factors (hCG/LIF/PIF) were found to be essential and pregnancy-specific. These molecules, besides others, may provide viable target for immunocontraception. The contraceptive vaccines targeting factors involved in pregnancy establishment have two potential concerns: 1) Although these factors are involved in the early events of embryonic development and preimplantation, the vaccines against them are not contraceptives in true sense because they target the post-fertilization stages, and 2) They are “self” molecules and it may be a challenging proposition to induce enough antibodies to neutralize these factors. However, the findings of phase I and phase II clinical trials of hCG vaccine in women indicate that by using appropriate carriers and adjuvants, one can modulate the “self” molecule to break its tolerance and raise an immune response against these molecules in humans. Also, the hCG vaccine trials indicate that there is no teratogenic effect of the low titer residual antibodies left after the protective levels decline. The hCG vaccine trials in women have established the basis for developing a birth control vaccine, targeting various factors involved in establishment of pregnancy. A multiepitope vaccine combining factors/antigens involved in various steps of fertilization cascade and pregnancy establishment, may provide a highly immunogenic and efficacious modality for contraception in humans.

Table II.

Chemokines and Growth Factors Involved in the Establishment of Pregnancy

| Protein | Size | Human Gene | Role | Species | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemokines | CCL-2 (MCP-1) | ~11 kDa | CCL2 | recruits monocytes, macrophages and T cells in the endometrium 89, 92, 93, 95 | human/mouse |

| CCL-3 (MIP1α) | 7.9 kDa | CCL3 | recruits macrophages94 | human/mouse | |

| CCL-4 (MIP-1β) | 7.62 kDa | CCL4 | recruits macrophages and NK cells; promotes trophoblast migration 34, 85 | human | |

| CCL5 (RANTES) | 8 kDa | CCL5 | recruits macrophages; high levels negatively affect fertilization 89, 92, 94 | human/mouse | |

| CCL-7 (MCP-3) | 8.5 kDa | CCL7 | recruits macrophages and NK cells; implantation requires a downregulation 85, 96 | mouse | |

| CXCL1 (GRO1; KC) | ~11 kDa | CXCL1 | upregulates the inflammatory response 94, 100 | human/mouse | |

| IL-8 (CXCL8) | 8.5 kDa | IL8 | regulates expression of inflammatory response genes 100, 112 | human | |

| CX3CL1 (fractalkine) | 90 kDa | CX3CL1 | recruits macrophages and NK cells; promotes trophoblast migration; regulates gene expression for adhesion 34, 48, 98 | human | |

| EGF Family | Amphiregulin (AREG) | 9.5–16.5 kDa | AREG | regulated by LIF, important in implantation 18, 19 | mouse |

| Epidermal growth factor (EGF) | ~6 kDa | EGF | stimulates trophoblast migration/invasion 35, 36 | human/mouse | |

| Heparin binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) | 22 kDa | HB-EGF | regulated by LIF; promotes development of blastocyst, motility, attachment and invasion 18, 24 | human/mouse | |

| Transforming growth factor α (TGFα) | 17 kDa | TGFA | increases the rate of blastocoel expansion 28 | mouse | |

| Growth Factors | Acrogranin/progranulin | 68 kDa | GRN | promotes blastocyst hatching, adhesion and outgrowth 29, 30 | mouse |

| Basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2, bFGF) | 18–22 kDa | FGF2 | prepares blastocyst for migration 25 | mouse | |

| Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) | ~38 kDa | CTGF | regulates uterine function 87, 88 | human/mouse | |

| Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) | 78 kDa | HGF | regulates cytotrophoblast differentiation and depth of invasion 26 | human | |

| Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-A) | 16 kDa | PDGFA | promotes trophoblast outgrowth 27 | mouse | |

| Prokineticin 1 (PROK1) | 9.7 kDa | EGVEGF | promotes expression of implantation-related genes (i.e. LIF) 40, 41 | human | |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-A) | 45 kDa | VEGFA | maintains corpus lutuem67 | human |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH Grant HD24425 to RKN. We thank Briana Shiley and Meghan Hatfield for excellent typing and editorial assistance.

Biography

Dr Rajesh K. Naz, Reproductive Immunology and Molecular Biology Laboratories, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, West Virginia University, School of Medicine, Morgantown, WV, USA

References

- 1.Duc-Goiran P, Mignot TM, Bourgeois C, Ferre F. Embryo-maternal interactions at the implantation site: a delicate equilibrium. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;83:85–100. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talwar GP, Singh O, Pal R, Chatterjee N, Sahai P, Dhall K, Kaur J, Das SK, Suri S, Buckshee K. A vaccine that prevents pregnancy in women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8532–8536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh M, Das SK, Suri S, Singh O, Talwar GP. Regain of fertility and normality of progeny born during below protective threshold antibody titers in women immunized with the HSD-hCG vaccine. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1998;39:395–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Yair E, Less A, Lev S, Ben-Yehoshua L, Tartakovsky B. Tumour necrosis factor alpha binding to human and mouse trophoblast. Cytokine. 1997;9:830–836. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winger EE, Reed JL. Treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and intravenous immunoglobulin improves live birth rates in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;60:8–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark DA. Should anti-TNF-alpha therapy be offered to patients with infertility and recurrent spontaneous abortion? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2009;61:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao LV, Wikarczuk ML, Heyner S. Functional roles of insulin and insulin-like growth factors in preimplantation mouse embryo development. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1990;26:1043–1048. doi: 10.1007/BF02624438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koizumi N, Fukuta K. Effect of insulin on in vitro development of tetraploid mouse embryos. Exp Anim. 1996;45:179–181. doi: 10.1538/expanim.45.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang TH, Chang CL, Wu HM, Chiu YM, Chen CK, Wang HS. Insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF-II), IGF-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3), and IGFBP-4 in follicular fluid are associated with oocyte maturation and embryo development. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1392–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Neill C. Autocrine mediators are required to act on the embryo by the 2-cell stage to promote normal development and survival of mouse preimplantation embryos in vitro. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:1303–1309. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.5.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaye PL, Harvey MB. The role of growth factors in preimplantation development. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1995;6:1–24. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(95)00001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham CH, Lysiak JJ, McCrae KR, Lala PK. Localization of transforming growth factor-beta at the human fetal-maternal interface: role in trophoblast growth and differentiation. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:561–572. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingman WV, Robker RL, Woittiez K, Robertson SA. Null mutation in transforming growth factor beta1 disrupts ovarian function and causes oocyte incompetence and early embryo arrest. Endocrinology. 2006;147:835–845. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robertson SA, Sjoblom C, Jasper MJ, Norman RJ, Seamark RF. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor promotes glucose transport and blastomere viability in murine preimplantation embryos. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:1206–1215. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.4.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjoblom C, Wikland M, Robertson SA. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) acts independently of the beta common subunit of the GM-CSF receptor to prevent inner cell mass apoptosis in human embryos. Biol Reprod. 2002;67:1817–1823. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.101.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rappolee DA, Sturm KS, Behrendtsen O, Schultz GA, Pedersen RA, Werb Z. Insulin-like growth factor II acts through an endogenous growth pathway regulated by imprinting in early mouse embryos. Genes Dev. 1992;6:939–952. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajesh H, Yong YY, Zhu M, Chia D, Yu SL. Growth hormone deficiency and supplementation at in-vitro fertilisation. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:514–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song H, Lim H, Das SK, Paria BC, Dey SK. Dysregulation of EGF family of growth factors and COX-2 in the uterus during the preattachment and attachment reactions of the blastocyst with the luminal epithelium correlates with implantation failure in LIF-deficient mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1147–1161. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherwin JR, Freeman TC, Stephens RJ, Kimber S, Smith AG, Chambers I, Smith SK, Sharkey AM. Identification of genes regulated by leukemia-inhibitory factor in the mouse uterus at the time of implantation. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2185–2195. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohamet L, Heath JK, Kimber SJ. Determining the LIF-sensitive period for implantation using a LIF-receptor antagonist. Reproduction. 2009;138:827–836. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez CI, Cheng JG, Liu L, Stewart CL. Cochlin, a secreted von Willebrand factor type a domain-containing factor, is regulated by leukemia inhibitory factor in the uterus at the time of embryo implantation. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1410–1418. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, Kontgen F, Abbondanzo SJ. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature. 1992;359:76–79. doi: 10.1038/359076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White CA, Zhang JG, Salamonsen LA, Baca M, Fairlie WD, Metcalf D, Nicola NA, Robb L, Dimitriadis E. Blocking LIF action in the uterus by using a PEGylated antagonist prevents implantation: a nonhormonal contraceptive strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19357–19362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710110104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jessmon P, Leach RE, Armant DR. Diverse functions of HBEGF during pregnancy. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:1116–1127. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burdsal CA, Flannery ML, Pedersen RA. FGF-2 alters the fate of mouse epiblast from ectoderm to mesoderm in vitro. Dev Biol. 1998;198:231–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill JA. Maternal-embryonic cross-talk. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;943:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kane MT, Morgan PM, Coonan C. Peptide growth factors and preimplantation development. Hum Reprod Update. 1997;3:137–157. doi: 10.1093/humupd/3.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harada T, Fujikawa T, Yoshida S, Onohara Y, Tanikawa M, Terakawa N. Expression of transforming growth factoralpha (TGF-alpha) gene in mouse embryonic development. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1997;14:262–269. doi: 10.1007/BF02765827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diaz-Cueto L, Stein P, Jacobs A, Schultz RM, Gerton GL. Modulation of mouse preimplantation embryo development by acrogranin (epithelin/granulin precursor) Dev Biol. 2000;217:406–418. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin J, Diaz-Cueto L, Schwarze JE, Takahashi Y, Imai M, Isuzugawa K, Yamamoto S, Chang KT, Gerton GL, Imakawa K. Effects of progranulin on blastocyst hatching and subsequent adhesion and outgrowth in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:434–442. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.040030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith RM, Garside WT, Aghayan M, Shi CZ, Shah N, Jarett L, Heyner S. Mouse preimplantation embryos exhibit receptor-mediated binding and transcytosis of maternal insulin-like growth factor I. Biol Reprod. 1993;49:1–12. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod49.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawamura K, Sato N, Fukuda J, Kodama H, Kumagai J, Tanikawa H, Murata M, Tanaka T. The role of leptin during the development of mouse preimplantation embryos. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;202:185–189. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Liu WM, Cao YJ, Peng S, Zhang Y, Duan EK. Roles of Dickkopf-1 and its receptor Kremen1 during embryonic implantation in mice. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1470–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hannan NJ, Jones RL, White CA, Salamonsen LA. The chemokines, CX3CL1, CCL14, and CCL4, promote human trophoblast migration at the feto-maternal interface. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:896–904. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.045518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright JK, Dunk CE, Perkins JE, Winterhager E, Kingdom JC, Lye SJ. EGF modulates trophoblast migration through regulation of Connexin 40. Placenta. 2006;27 (Suppl A):S114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu Q, Yangi MY, Tsang BK, Gruslin A. Both mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signalling are required in epidermal growth factor-induced human trophoblast migration. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:677–684. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabir-Salmani M, Shiokawa S, Akimoto Y, Sakai K, Iwashita M. The role of alpha(5)beta(1)-integrin in the IGF-I-induced migration of extravillous trophoblast cells during the process of implantation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:91–97. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabir-Salmani M, Shiokawa S, Akimoto Y, Sakai K, Nagamatsu S, Nakamura Y, Lotfi A, Kawakami H, Iwashita M. Alphavbeta3 integrin signaling pathway is involved in insulin-like growth factor I-stimulated human extravillous trophoblast cell migration. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1620–1630. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones RL, Stoikos C, Findlay JK, Salamonsen LA. TGF-beta superfamily expression and actions in the endometrium and placenta. Reproduction. 2006;132:217–232. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans J, Catalano RD, Morgan K, Critchley HO, Millar RP, Jabbour HN. Prokineticin 1 signaling and gene regulation in early human pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2877–2887. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans J, Catalano RD, Brown P, Sherwin R, Critchley HO, Fazleabas AT, Jabbour HN. Prokineticin 1 mediates fetal-maternal dialogue regulating endometrial leukemia inhibitory factor. FASEB J. 2009;23:2165–2175. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-124495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheon YP, Xu X, Bagchi MK, Bagchi IC. Immune-responsive gene 1 is a novel target of progesterone receptor and plays a critical role during implantation in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5623–5630. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirota Y, Osuga Y, Hasegawa A, Kodama A, Tajima T, Hamasaki K, Koga K, Yoshino O, Hirata T, Harada M, Takemura Y, Yano T, Tsutsumi O, Taketani Y. Interleukin (IL)-1beta stimulates migration and survival of first-trimester villous cytotrophoblast cells through endometrial epithelial cell-derived IL-8. Endocrinology. 2009;150:350–356. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon C, Moreno C, Remohi J, Pellicer A. Molecular interactions between embryo and uterus in the adhesion phase of human implantation. Hum Reprod. 1998;13 (Suppl 3):219–232. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.suppl_3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonzalez RR, Devoto L, Campana A, Bischof P. Effects of leptin, interleukin-1alpha, interleukin-6, and transforming growth factor-beta on markers of trophoblast invasive phenotype: integrins and metalloproteinases. Endocrine. 2001;15:157–164. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:15:2:157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karagouni EE, Chryssikopoulos A, Mantzavinos T, Kanakas N, Dotsika EN. Interleukin-1beta and interleukin-1alpha may affect the implantation rate of patients undergoing in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:553–559. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simon C, Valbuena D, Krussel J, Bernal A, Murphy CR, Shaw T, Pellicer A, Polan ML. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents embryonic implantation by a direct effect on the endometrial epithelium. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:896–906. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hannan NJ, Salamonsen LA. CX3CL1 and CCL14 regulate extracellular matrix and adhesion molecules in the trophoblast: potential roles in human embryo implantation. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:58–65. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White FJ, Burghardt RC, Hu J, Joyce MM, Spencer TE, Johnson GA. Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (osteopontin) is expressed by stromal macrophages in cyclic and pregnant endometrium of mice, but is induced by estrogen in luminal epithelium during conceptus attachment for implantation. Reproduction. 2006;132:919–929. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim J, Erikson DW, Burghardt RC, Spencer TE, Wu G, Bayless KJ, Johnson GA, Bazer FW. Secreted phosphoprotein 1 binds integrins to initiate multiple cell signaling pathways, including FRAP1/mTOR, to support attachment and force-generated migration of trophectoderm cells. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugihara K, Sugiyama D, Byrne J, Wolf DP, Lowitz KP, Kobayashi Y, Kabir-Salmani M, Nadano D, Aoki D, Nozawa S, Nakayama J, Mustelin T, Ruoslahti E, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda MN. Trophoblast cell activation by trophinin ligation is implicated in human embryo implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3799–3804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611516104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Braga VM, Gendler SJ. Modulation of Muc-1 mucin expression in the mouse uterus during the estrus cycle, early pregnancy and placentation. J Cell Sci. 1993;105:397–405. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dharmaraj N, Gendler SJ, Carson DD. Expression of human MUC1 during early pregnancy in the human MUC1 transgenic mouse model. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:1182–1188. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.079418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carson DD, Tang JP, Julian J. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan (perlecan) expression by mouse embryos during acquisition of attachment competence. Dev Biol. 1993;155:97–106. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshinaga K. Research on Blastocyst Implantation Essential Factors (BIEFs) Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:413–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duzyj CM, Barnea ER, Li M, Huang SJ, Krikun G, Paidas MJ. Preimplantation factor promotes first trimester trophoblast invasion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:e401–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paidas MJ, Krikun G, Huang SJ, Jones R, Romano M, Annunziato J, Barnea ER. A genomic and proteomic investigation of the impact of preimplantation factor on human decidual cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:e451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ye X, Hama K, Contos JJ, Anliker B, Inoue A, Skinner MK, Suzuki H, Amano T, Kennedy G, Arai H, Aoki J, Chun J. LPA3-mediated lysophosphatidic acid signalling in embryo implantation and spacing. Nature. 2005;435:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature03505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hama K, Aoki J, Inoue A, Endo T, Amano T, Motoki R, Kanai M, Ye X, Chun J, Matsuki N, Suzuki H, Shibasaki M, Arai H. Embryo spacing and implantation timing are differentially regulated by LPA3-mediated lysophosphatidic acid signaling in mice. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:954–959. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.060293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song H, Lim H, Paria BC, Matsumoto H, Swift LL, Morrow J, Bonventre JV, Dey SK. Cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha is crucial [correction of A2alpha deficiency is crucial] for ‘on-time’ embryo implantation that directs subsequent development. Development. 2002;129:2879–2889. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie H, Wang H, Tranguch S, Iwamoto R, Mekada E, Demayo FJ, Lydon JP, Das SK, Dey SK. Maternal heparin-binding-EGF deficiency limits pregnancy success in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18315–18320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707909104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang X, Green KE, Yallampalli C, Dong YL. Adrenomedullin enhances invasion by trophoblast cell lines. BiolReprod. 2005;73:619–626. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.040436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li M, Yee D, Magnuson TR, Smithies O, Caron KM. Reduced maternal expression of adrenomedullin disrupts fertility, placentation, and fetal growth in mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2653–2662. doi: 10.1172/JCI28462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li M, Wu Y, Caron KM. Haploinsufficiency for adrenomedullin reduces pinopodes and diminishes uterine receptivity in mice. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:1169–1175. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.069336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gonzalez RR, Caballero-Campo P, Jasper M, Mercader A, Devoto L, Pellicer A, Simon C. Leptin and leptin receptor are expressed in the human endometrium and endometrial leptin secretion is regulated by the human blastocyst. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4883–4888. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nardo LG, Nikas G, Makrigiannakis A. Molecules in blastocyst implantation. Role of matrix metalloproteinases, cytokines and growth factors. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:137–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sugino N, Kashida S, Takiguchi S, Karube A, Kato H. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in the human corpus luteum during the menstrual cycle and in early pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3919–3924. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Segerer SE, Muller N, Brandt J, Kapp M, Dietl J, Reichardt HM, Rieger L, Kammerer U. The glycoprotein-hormones activin A and inhibin A interfere with dendritic cell maturation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2008;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jones RL, Findlay JK, Farnworth PG, Robertson DM, Wallace E, Salamonsen LA. Activin A and inhibin A differentially regulate human uterine matrix metalloproteinases: potential interactions during decidualization and trophoblast invasion. Endocrinology. 2006;147:724–732. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Menkhorst E, Salamonsen LA, Zhang J, Harrison CA, Gu J, Dimitriadis E. Interleukin 11 and activin A synergise to regulate progesterone-induced but not cAMP-induced decidualization. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;84:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bilinski P, Roopenian D, Gossler A. Maternal IL-11Ralpha function is required for normal decidua and fetoplacental development in mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2234–2243. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Karpovich N, Klemmt P, Hwang JH, McVeigh JE, Heath JK, Barlow DH, Mardon HJ. The production of interleukin-11 and decidualization are compromised in endometrial stromal cells derived from patients with infertility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1607–1612. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robb L, Li R, Hartley L, Nandurkar HH, Koentgen F, Begley CG. Infertility in female mice lacking the receptor for interleukin 11 is due to a defective uterine response to implantation. Nat Med. 1998;4:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meisser A, Cameo P, Islami D, Campana A, Bischof P. Effects of interleukin-6 (IL-6) on cytotrophoblastic cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:1055–1058. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.11.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dimitriadis E, White CA, Jones RL, Salamonsen LA. Cytokines, chemokines and growth factors in endometrium related to implantation. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11:613–630. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reese J, Binart N, Brown N, Ma WG, Paria BC, Das SK, Kelly PA, Dey SK. Implantation and decidualization defects in prolactin receptor (PRLR)-deficient mice are mediated by ovarian but not uterine PRLR. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1872–1881. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.5.7464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perrier d’Hauterive S, Charlet-Renard C, Berndt S, Dubois M, Munaut C, Goffin F, Hagelstein MT, Noel A, Hazout A, Foidart JM, Geenen V. Human chorionic gonadotropin and growth factors at the embryonic-endometrial interface control leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) secretion by human endometrial epithelium. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2633–2643. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sales KJ, Grant V, Catalano RD, Jabbour HN. Chorionic gonadotropin regulates CXCR4 Expression In Human Endometrium Via E-Series Prostanoid Receptor 2 signalling to PI3K-ERK1/2: implications for fetal-maternal cross-talk for embryo implantation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2011;17:22–32. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lim H, Paria BC, Das SK, Dinchuk JE, Langenbach R, Trzaskos JM, Dey SK. Multiple female reproductive failures in cyclooxygenase 2-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;91:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scherle PA, Ma W, Lim H, Dey SK, Trzaskos JM. Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 induction in the mouse uterus during decidualization. An event of early pregnancy. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37086–37092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gendron RL, Paradis H, Hsieh-Li HM, Lee DW, Potter SS, Markoff E. Abnormal uterine stromal and glandular function associated with maternal reproductive defects in Hoxa-11 null mice. Biol Reprod. 1997;56:1097–1105. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod56.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lim H, Ma L, Ma WG, Maas RL, Dey SK. Hoxa-10 regulates uterine stromal cell responsiveness to progesterone during implantation and decidualization in the mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1005–1017. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.6.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Godbole G, Modi D. Regulation of decidualization, interleukin-11 and interleukin-15 by homeobox A 10 in endometrial stromal cells. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;85:130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Benson GV, Lim H, Paria BC, Satokata I, Dey SK, Maas RL. Mechanisms of reduced fertility in Hoxa-10 mutant mice: uterine homeosis and loss of maternal Hoxa-10 expression. Development. 1996;122:2687–2696. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Salamonsen LA, Hannan NJ, Dimitriadis E. Cytokines and chemokines during human embryo implantation: rolesin implantation and early placentation. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:437–444. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Surveyor GA, Wilson AK, Brigstock DR. Localization of connective tissue growth factor during the period of embryo implantation in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:1207–1213. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.5.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Uzumcu M, Homsi MF, Ball DK, Coskun S, Jaroudi K, Hollanders JM, Brigstock DR. Localization of connective tissue growth factor in human uterine tissues. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:1093–1098. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.12.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rageh MA, Moussad EE, Wilson AK, Brigstock DR. Steroidal regulation of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2; CTGF) synthesis in the mouse uterus. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:338–346. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.5.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wood GW, Hausmann E, Choudhuri R. Relative role of CSF-1, MCP-1/JE, and RANTES in macrophage recruitment during successful pregnancy. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;46:62–69. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199701)46:1<62::AID-MRD10>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Litwin S, Lagadari M, Barrientos G, Roux ME, Margni R, Miranda S. Comparative immunohistochemical study of M-CSF and G-CSF in feto-maternal interface in a multiparity mouse model. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;54:311–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pollard JW, Hunt JS, Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W, Stanley ER. A pregnancy defect in the osteopetrotic (op/op) mouse demonstrates the requirement for CSF-1 in female fertility. Dev Biol. 1991;148:273–283. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Caballero-Campo P, Dominguez F, Coloma J, Meseguer M, Remohi J, Pellicer A, Simon C. Hormonal and embryonic regulation of chemokines IL-8, MCP-1 and RANTES in the human endometrium during the window of implantation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:375–384. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Garcia-Velasco JA, Arici A. Chemokines and human reproduction. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:983–993. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wood GW, Hausmann EH, Kanakaraj K. Expression and regulation of chemokine genes in the mouse uterus during pregnancy. Cytokine. 1999;11:1038–1045. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meter RA, Wira CR, Fahey JV. Secretion of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 by human uterine epithelium directs monocyte migration in culture. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nautiyal J, Kumar PG, Laloraya M. Mifepristone (Ru486) antagonizes monocyte chemotactic protein-3 down-regulation at early mouse pregnancy revealing immunomodulatory eventsin Ru486 induced abortion. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;52:8–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Popovici RM, Betzler NK, Krause MS, Luo M, Jauckus J, Germeyer A, Bloethner S, Schlotterer A, Kumar R, Strowitzki T, von Wolff M. Gene expression profiling of human endometrial-trophoblast interaction in a coculture model. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5662–5675. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jones RL, Hannan NJ, Kaitu’u TJ, Zhang J, Salamonsen LA. Identification of chemokines important for leukocyte recruitment to the human endometrium at the times of embryo implantation and menstruation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6155–6167. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Uz YH, Murk W, Yetkin CE, Kayisli UA, Arici A. Expression and role of interleukin-23 in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle and early pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;87:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.06.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hess AP, Hamilton AE, Talbi S, Dosiou C, Nyegaard M, Nayak N, Genbecev-Krtolica O, Mavrogianis P, Ferrer K, Kruessel J, Fazleabas AT, Fisher SJ, Giudice LC. Decidual stromal cell response to paracrine signals from the trophoblast: amplification of immune andangiogenic modulators. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:102–117. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.054791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Koga K, Aldo PB, Mor G. Toll-like receptors and pregnancy: Trophoblast as modulators of the immune response. J ObstetGynecol Res. 2009;35:191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xie X, Kang Z, Anderson LN, He H, Lu B, Anne Croy B. Analysis of the contributions of L-selectin and CXCR3 in mediating leukocyte homing to pregnant mouse uterus. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;53:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang B, Sheng JZ, He RH, Qian YL, Jin F, Huang HF. High expression of L-selectin ligand in secretory endometrium is associated with better endometrial receptivity and facilitates embryo implantation in human being. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;60:127–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ledee-Bataille N, Dubanchet S, Coulomb-L’hermine A, Durand-Gasselin I, Frydman R, Chaouat G. A new rolefor natural killer cells, interleukin (IL)-12, and IL-18 in repeated implantation failure after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tokmadzic VS, Tsuji Y, Bogovic T, Laskarin G, Cupurdija K, Strbo N, Koyama K, Okamura H, Podack ER, Rukavina D. IL-18 is present at the maternal-fetal interface and enhances cytotoxic activity of decidual lymphocytes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2002;48:191–200. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2002.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kralickova M, Sima P, Rokyta Z. Role of the leukemia-inhibitory factor gene mutations in infertile women: the embryo-endometrial cytokine cross talk during implantation--a delicate homeostatic equilibrium. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2005;50:179–186. doi: 10.1007/BF02931563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murphy SP, Fast LD, Hanna NN, Sharma S. Uterine NK cells mediate inflammation-induced fetal demise in IL-10-null mice. J Immunol. 2005;175:4084–4090. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mas AE, Petitbarat M, Dubanchet S, Fay S, Ledee N, Chaouat G. Immune regulation at the interface during early steps of murine implantation: involvement of two new cytokines of the IL-12 family (IL-23 and IL-27) and of TWEAK. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59:323–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vigne JL, Hornung D, Mueller MD, Taylor RN. Purification and characterization of an immunomodulatory endometrial protein, glycodelin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17101–17105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Scholz C, Toth B, Brunnhuber R, Rampf E, Weissenbacher T, Santoso L, Friese K, Jeschke U. Glycodelin A induces a tolerogenic phenotype in monocyte-derived dendritic cells in vitro. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;60:501–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Clark DA, Fernandes J, Banwatt D. Prevention of spontaneous abortion in the CBA x DBA/2 mouse model by intravaginal TGF-beta and local recruitment of CD4+8+ FOXP3+ cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59:525–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Petkovic AB, Matic SM, Stamatovic NV, Vojvodic DV, Todorovic TM, Lazic ZR, Kozomara RJ. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1beta and TNF-alpha) and chemokines (IL-8 and MIP-1alpha) as markers of peri-implant tissue condition. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Petitbarat M, Serazin V, Dubanchet S, Wayner R, de Mazancourt P, Chaouat G, Ledee N. Tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK)/fibroblast growth factor inducible-14 might regulate the effects of interleukin 18 and 15 in the human endometrium. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1141–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Athanassakis I, Farmakiotis V, Aifantis I, Gravanis A, Vassiliadis S. Expression of corticotrophin-releasing hormone in the mouse uterus: participation in embryo implantation. J Endocrinol. 1999;163:221–227. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1630221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Makrigiannakis A, Zoumakis E, Kalantaridou S, Coutifaris C, Margioris AN, Coukos G, Rice KC, Gravanis A, Chrousos GP. Corticotropin-releasing hormone promotes blastocyst implantation and early maternal tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1018–1024. doi: 10.1038/ni719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cole LA. Biological functions of hCG and hCG-related molecules. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:102. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Austin KJ, Bany BM, Belden EL, Rempel LA, Cross JC, Hansen TR. Interferon-stimulated gene-15 (Isg15) expression is up-regulated in the mouse uterus in response to the implanting conceptus. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3107–3113. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Roth I, Corry DB, Locksley RM, Abrams JS, Litton MJ, Fisher SJ. Human placental cytotrophoblasts produce the immunosuppressive cytokine interleukin 10. J Exp Med. 1996;184:539–548. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Charnock-Jones DS, Sharkey AM, Fenwick P, Smith SK. Leukaemia inhibitory factor mRNA concentration peaks in human endometrium at the time of implantation and the blastocyst contains mRNA for the receptor at this time. J Reprod Fertil. 1994;101:421–426. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1010421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Delage G, Moreau JF, Taupin JL, Freitas S, Hambartsoumian E, Olivennes F, Fanchin R, Letur-Konirsch H, Frydman R, Chaouat G. In-vitro endometrial secretion of human interleukin for DA cells/leukaemia inhibitory factor by explant cultures from fertile and infertile women. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2483–2488. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tsai HD, Chang CC, Hsieh YY, Lo HY. Leukemia inhibitory factor expression in different endometrial locations between fertile and infertile women throughout different menstrual phases. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2000;17:415–418. doi: 10.1023/A:1009457016871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Novotny Z, Krizan J, Sima R, Sima P, Uher P, Zech N, Hutelova R, Baborova P, Ulcova-Gallova Z, Subrt I, Ulmanova E, Houdek Z, Rokyta Z, Babuska V, Kralickova M. Leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) gene mutations in women diagnosed with unexplained infertility and endometriosis have a negative impact on the IVF outcome. A pilot study. Folia Biol (Praha) 2009;55:92–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.O’Day-Bowman MB, Mavrogianis PA, Reuter LM, Johnson DE, Fazleabas AT, Verhage HG. Association of oviduct-specific glycoproteins with human and baboon (Papio anubis) ovarian oocytes and enhancement of human sperm binding to human hemizonae following in vitro incubation. Biol Reprod. 1996;54:60–69. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Seppala M, Koistinen H, Koistinen R, Chiu PCN, Yeung WSB. Glycosylation related actions of glycodelin: gamete, cumulus cell, immune cell and clinical associations. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:275–287. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nakayama J, Aoki D, Suga T, Akama TO, Ishizone S, Yamaguchi H, Imakawa K, Nadano D, Fazleabas AT, Katsuyama T, Nozawa S, Fukuda MN. Implantation-dependent expression of trophinin by maternal fallopian tube epithelia during tubal pregnancies -Possible role of human chorionic gonadotrophin on ectopic pregnancy. Am J Path. 2003;163:2211–2219. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]