Abstract

Coupled with over-expression in host organisms, fusion protein systems afford economical methods to obtain large quantities of target proteins in a fast and efficient manner. Some proteases used for these purposes cleave C-terminal to their recognition sequences and do not leave extra amino acids on the target. However, they are often inefficient and are frequently promiscuous, resulting in non-specific cleavages of the target protein. To address these issues, we created a fusion protein system that utilizes a highly efficient enzyme and leaves no residual amino acids on the target protein after removal of the affinity tag. We designed a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fusion protein vector with a caspase-3 consensus cleavage sequence located between the N-terminal GST tag and a target protein. We show that the enzyme efficiently cleaves the fusion protein without leaving excess amino acids on the target protein. In addition, we used an engineered caspase-3 enzyme that is highly stable, has increased activity relative to the wild-type enzyme, and contains a poly-histidine tag that allows for efficient removal of the enzyme after cleavage of the fusion protein. Although we have developed this system using a GST tag, the system is amenable to any commercially available affinity tag.

Keywords: Caspase-3, Fusion protein, Protein expression, Proteolysis

In the past thirty years, a number of protein purification systems have been developed using fusion proteins to aid in the efficient purification and recovery of recombinant proteins from crude cell extracts or culture media. These systems incorporate amino- or carboxy-terminal proteins or peptides referred to as “tags.” Many of the tags can be removed subsequent to binding to, or while concurrently bound to, a high affinity matrix. Matrices for binding the tags have generally incorporated immobilized metal for binding poly-histidine sequences, immobilized glutathione for binding glutathione S-transferase (GST),1 poly-alanine affinity matrices, antigenic epitopes to bind monoclonal antibodies, biotinylated resins for binding avidin or strep-avidin, carbohydrate-binding proteins, or even complete enzymes immobilized in a matrix for substrate binding [1]. While tags provide many advantages for aiding in the rapid recovery, stabilization, and increased scale of protein expression, many tags interfere with protein structure and function and must be removed after purification of the fusion protein. Removal of the tags usually occurs by cleavage of the fusion protein by a specific protease, such as thrombin.

The most widely used carrier proteins, or tags, for over-expression of proteins in Escherichia coli are Schistosoma japonicum glutathione S-transferase (GST) [2], E. coli maltose-binding protein (MBP) [3], and E. coli thioredoxin [4]. Recently, three additional E. coli proteins, NusA, GrpE, and bacterioferritin have been introduced as carriers for increasing the solubility of proteins over-expressed in E. coli [5]. By fusing these proteins to the N-terminus of a protein of interest, the solubility of the target protein can be increased dramatically relative to the non-fused protein when over-expressed at 37 °C [5].

It is sometimes problematic, however, to remove the entire carrier protein sequence without leaving residual amino acids on the target protein. For example, the proteases most frequently used to remove carrier proteins are thrombin, factor Xa, and enterokinase. Factor Xa and enterokinase cleave C-terminal to their recognition sequences, leaving no residual amino acids. Thrombin, however, cleaves the amino acid sequence LVPR/GS between R and G, which leaves two amino acids (GS), called an overhang, at the amino terminus of the target protein. All three enzymes have been shown to cleave proteins at non-canonical sites [6–10], which negates the advantages afforded by the carrier protein. To circumvent these problems, two additional proteases, rhinovirus 3C protease (called PreScission protease) and the nuclear inclusion protease encoded by tobacco etch virus (TEV), have been introduced to the marketplace. While these proteases may exhibit a higher specificity than the previous enzymes, both enzymes leave overhangs on the target protein. PreScission protease leaves a dipeptide overhang (GP) after cleaving the sequence LGVLFQ/GP, and TEV protease leaves a single amino acid overhang (G) after cleaving the consensus sequence EXXYXQ/G [11]. In addition, the relatively low activity or specificity of some enzymes used to cleave fusion proteins can result in tedious and expensive experiments, making this approach unappealing for clinical or bioindus-trial purposes [12].

Here, we offer an alternative purification system that addresses the issues of low specificity and of leaving overhangs on the target protein. By incorporating a caspase-3 cleavage recognition sequence into a GST-fusion protein, we have made a complete purification system that utilizes a well characterized enzyme. Caspase-3 is not only highly active but also cleaves with high specificity C-terminal to DXXD motifs found in flexible protein regions, leaving no residual amino acids on the N-terminus of the target protein. By incorporating a poly-histidine tag into the caspase-3 sequence, we generated an enzyme that can be purified easily from the target protein.

Materials and methods

Materials

Trizma base, glutathione, dibasic and monobasic potassium phosphate, and NaCl were from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, New Hampshire, USA). Plasmid pGEX-2T and XK26/100 columns were from AP Biotech (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). GST Bind resin was from EMD Biosciences (Darmstadt, Germany). IPTG was from Anatrace (Maumee, Ohio, USA), thrombin was from Acros (Geel, Belgium), and ammonium bicarbonate was from Fluka Biochemika (subsidiary of Fisher Scientific). Protein assay reagent, Bio-Spin P-6 columns, and SDS were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, California, USA). Restriction endonucleases were from Stratagene (LaJolla, California, USA). Fused silica capillaries were from Polymicro Technologies LLC (Phoenix, Arizona, USA). YM10 membranes were from Millipore (Billerica, Massachusetts, USA). BSA, bromophenol blue, and glycerol were from Sigma (Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Cloning and protein expression

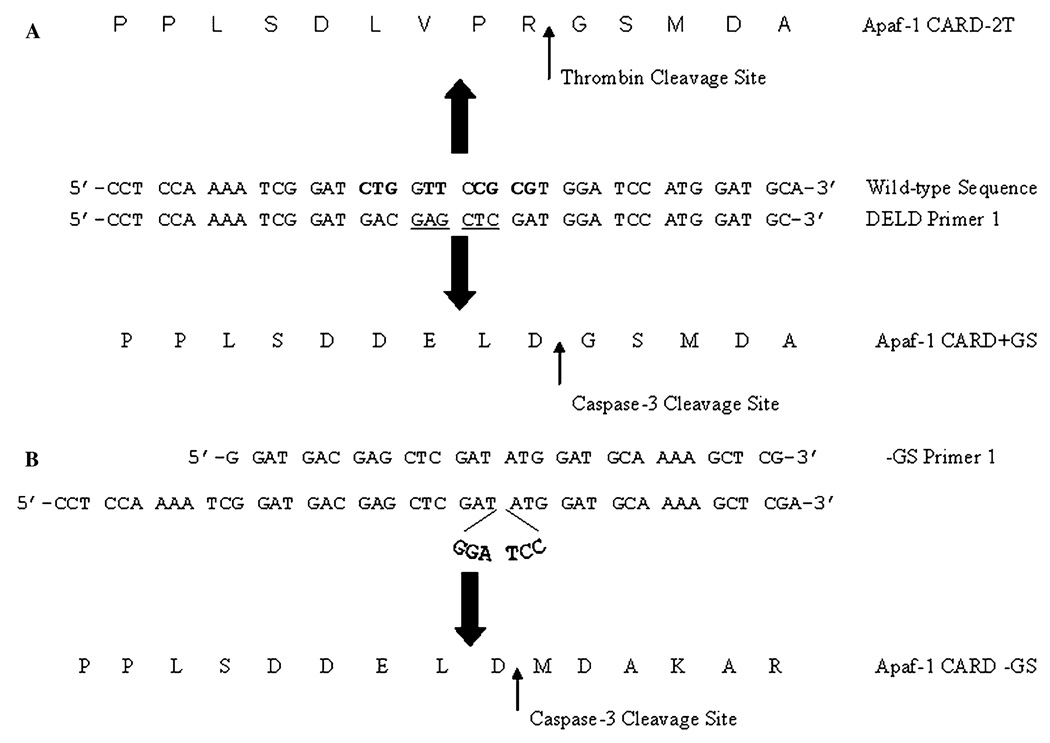

The First 97 amino acids of Apaf-1 CARD (GenBank Accession No. AF013263) were fused to GST by cloning the CARD domain into the pGEX-2T vector (GenBank Accession No. A01438, A01578, M21676, M97937) using Bam HI and Xho I restriction sites. The plasmid is abbreviated as pApaf-1CARD-2T, and the resulting protein is referred to as Apaf-1 CARD-2T. The DELD caspase-3 cleavage site was introduced into this clone by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis using DELD forward primer 5′-CCT CCA AAA TCG GAT GAC GAG CTC GAT GGA TCC ATG GAT GC-3′, and its reverse complement, DELD reverse primer 5′GCA TCC ATG GAT CCA TCG AGC TCG TCA TCC GAT TTT GGA GG-3′ (see Fig. 1). A Sac I site (underlined) was introduced for screening. The resulting plasmid is abbreviated as pApaf-1CARD + GS and yields a protein that contains a two amino acid overhang (GS) at the N-terminus of Apaf-1 CARD following cleavage with caspase-3. The protein is referred to as Apaf-1 CARD + GS. The GS overhang was removed from the gene using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis and the forward primer (−GS forward primer), 5′-G GAT GAC GAG CTC GAT ATG GAT GCA AAA GCT CG-3′, and its reverse complement (−GS reverse primer), 5′-CG AGC TTT TGC ATC CAT ATC GAG CTC GTC ATC C-3′. The resulting plasmid is abbreviated as pApaf-1CARD − GS, and the resulting protein is referred to as Apaf-1 CARD − GS. All three constructs were sequenced (both DNA strands) to confirm the sequence (University of Maine Sequencing Facility, Orono, Maine, USA).

Fig. 1.

Cloning GST-fusion protein constructs. (A) Schematic diagram of the strategy used to clone Apaf-1 CARD + GS incorporating a caspase-3 cleavage sequence (DELD). The mutated bases are shown in bold, and a Sac I restriction site is underlined. (B) Apaf-1 CARD −GS was cloned from the Apaf-1 CARD + GS construct to remove the two amino acid overhang (GS) at the amino terminus. The primers shown are the forward primers used in the cloning along with the appropriate coding sequences. Note that the primer for Apaf-1 CARD − GS removes six bases (GGATCC) encoding for the glycine and serine amino acids. Cleavage sites for thrombin and caspase-3 are indicated in the protein sequences.

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) harboring the appropriate plasmid was grown at 37 °C in LB media (1L) to an optical density of 1.2 at 600 nm, and protein expression was induced with 1mM IPTG. After 24 h of expression, cells were centrifuged at 5000 rpm (Sorvall GS-3) for 10min at 4 °C. Cells (13.8 g wet weight cells) were resuspended in 10mL of phosphate buffer (50mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, pH 7.5, 1mM DTT), and lysed using a French pressure cell system. The solutions were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm (Sorvall SA-600) for 20min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. To maximize the protein yield, the pellet was washed 4–5 times with phosphate buffer (20mL each wash). Following recentrifugation, the washes were combined with the original lysate. The lysate was divided in half, and each half was passed over a GST Bind Resin, using an XK26/100 water-jacketed thermostatic column containing approximately 185mL of resin. The temperature was maintained at 25 °C. The resin containing the protein was washed with phosphate buffer (Five column volumes), and the protein was eluted according to manufacturer’s instructions (www.apbiotech.com catalog no. 18-1157-58) using a buffer of 50mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10mM reduced glutathione. Prior to performing the cleavage reactions described below, the pH was adjusted to 7.5 (for reactions using caspase-3 or procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A)) using concentrated HCl. The protein was concentrated to approximately 2–3mg/mL using a stirred ultrafiltration cell (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) and YM10 membranes, and 1mM DTT was added. All proteins were analyzed on 15% polyacrylamide SDS–PAGE gels that were stained with coomassie brilliant blue. Purified fusion protein was either cleaved with the appropriate enzyme, as described below, or stored at −20 °C until required. Caspase-3 and procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A) were purified as previously described [13,14].

Determination of thrombin concentration

BSA standards were made in phosphate buffer to concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, or 1.0 µg/mL. The solutions were mixed 1:5 with protein assay reagent. Sample absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a Cary 50 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Varian, Palo Alto, California, USA). The results were plotted and linear regression performed to generate a standard curve. The A595 of thrombin was measured for solutions of 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, and 10U/mL in phosphate buffer, and the concentration was determined from the standard curve. The results showed that 1U of thrombin equals approximately 0.1mg of protein.

Limited proteolysis with thrombin and caspase-3

Proteins for cleavage with thrombin were incubated in phosphate buffer. Proteins for cleavage with caspase-3 or procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A) were incubated in a buffer of 50mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 50mM NaCl, 1mM DTT. The appropriate enzyme, in concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, and 1mg/mL, was incubated with fusion protein (1mg/mL) for 16 h at 25 °C. The Final reaction volume was 1mL. Aliquots of 50 µL were removed at the time intervals indicated in the Figures. Reactions were stopped by adding 10 µL of a 6× stock of SDS–PAGE loading buffer (300mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 600 mM DTT, 12% SDS, 0.6% bromophenol blue, 20% glycerol), and the samples were subsequently frozen at −20 °C until examined by gel electrophoresis. In the Figures, time zero refers to a reaction that was stopped immediately after mixing the fusion protein with the appropriate enzyme. Samples were analyzed on 15% SDS polyacrylamide gels, coomassie stained, and visualized using a Bio-Rad Quantity One gel imaging system.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Protein samples were buffer exchanged into 50mM NH4HCO3, pH 8.0, using micro Bio-Spin P-6 columns as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Eluted protein was lyophilized and resuspended in a solution of methanol/0.2% formic acid (1:1, v:v). The protein solution was infused directly through a 20 cm × 360 µm o.d. × 75 µm i.d. fused silica capillary at a flow rate of 1.5 µL/min and analyzed by an LCQ Deca ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, California, USA). Using an in-house built interface, electrospray ionization (ESI) was accomplished by applying 2.2 kV to a stainless steel union containing a flame-pulled capillary tip. The LCQ Deca was operated in high mass mode with a three point calibration. Data were acquired in the m/z range 1000–4000 for 1min with an experimental measurement error of 0.07%. ESI-MS spectra were deconvoluted using the Biomass calculation and deconvolution software (Bioworks 3.1, Thermo Finnigan) with scan averaging and three-point Gaussian smoothing over the entire acquisition period.

Results

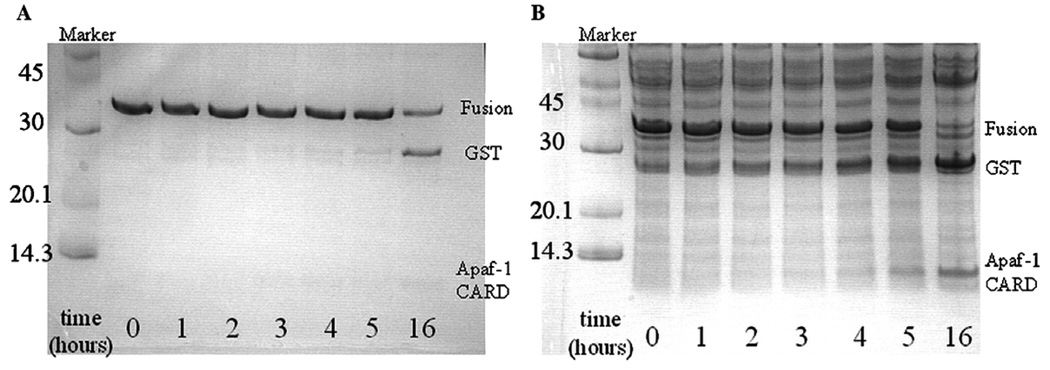

We have utilized a number of commercially available fusion proteins and other tags in our attempts to purify recombinant proteins following over-expression in E. coli. One such system utilizes the pGEX-2T vector to over-express a recombinant protein, the CARD domain of Apaf-1 (called Apaf-1 CARD). We found that when Apaf-1 CARD is expressed as part of a fusion protein with GST, the construct is very stable, resulting in yields of approximately 1 g of soluble fusion protein per liter of liquid culture (13.8 g wet weight cells). When we attempted to cleave the Apaf-1 CARD fusion protein with thrombin, however, we noticed a number of factors that made its purification uneconomical. For example, approximately 10,000U of thrombin were required to completely cleave 1 g of fusion protein in 16 h. In addition, regardless of the provider (Sigma, Acros, or AP Biotech), commercially available thrombin added a significant number of contaminants to the fusion protein (see Fig. 2), which offset the advantage of using a fusion protein for purification. As a result, we wished to produce a fusion protein that could be cleaved by a different enzyme, preferably one with higher activity, reasoning that fewer contaminants and byproducts would be introduced during the cleavage event. Moreover, an enzyme with higher activity would have the added benefit that the cleavage reaction could be performed in a few hours rather than 16 or more hours as required with thrombin. To accomplish this, we replaced the thrombin cleavage sequence with a caspase-3 cleavage sequence.

Fig. 2.

Limited proteolysis of Apaf-1 CARD-2T with thrombin. Apaf-1 CARD-2T (1mg) was incubated with 1 U of thrombin (~0.1mg) (A) or 10U of thrombin (~1mg) (B). Samples were removed at the indicated times, mixed with SDS loading buffer and frozen to quench the reaction. The 0 h sample represents fusion protein that was mixed with protease, then immediately removed as described. Sizes (in kilodalton) of molecular weight markers are shown next to each marker.

To mimic the N-terminal GS overhang resulting from thrombin cleavage, we incorporated a caspase-3 recognition sequence (DELD) to replace the First four residues in the thrombin recognition sequence (LVPRGS) (Fig. 1A). In addition, we removed the six nucleotides coding for the GS overhang to demonstrate that caspase-3 can efficiently remove all of the GST carrier protein, leaving no residual amino acids at the N-terminus of Apaf-1 CARD (Fig. 1B). These two constructs are referred to as Apaf-1 CARD + GS and Apaf-1 CARD − GS, respectively. We then performed limited proteolysis with thrombin or caspase-3 on Apaf-1 CARD-2T (thrombin cleavage), Apaf-1 CARD + GS and Apaf-1 CARD − GS. In addition to processing the fusion proteins with the wild-type caspase-3 enzyme, we also cleaved with a mutant caspase-3 enzyme, procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A). In this caspase variant, two processing sites that remove the pro-domain in the wild-type enzyme were removed. This results in a caspase in which the linker between the two subunits is cleaved (D175), yet the pro-domain remains attached. This enzyme has been shown to have higher activity (~25%), dramatically increased stability, and a greater yield from over-expression in E. coli [22].

As determined from a BSA assay, 1U of thrombin protease equals approximately 0.1mg of enzyme. We performed the cleavage reactions of Apaf-1 CARD-2T with thrombin at 1:1, 1:0.1, and 1:0.01 (wt:wt) concentrations of Apaf-1 CARD-2T to thrombin, corresponding to 10, 1, and 0.1U of thrombin, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2, 1U of thrombin cleaved nearly half of the fusion protein in 16 h (Fig. 2A), and approximately 10U of thrombin were required to cleave all of the fusion protein (1mg) in 16 h at 25 °C (Fig. 2B). However, the larger amount of thrombin added a significant number of contaminants to the sample (Fig. 2B). We were unable to observe any cleavage with 0.1U of thrombin when gels were visualized by coomassie brilliant blue staining (data not shown).

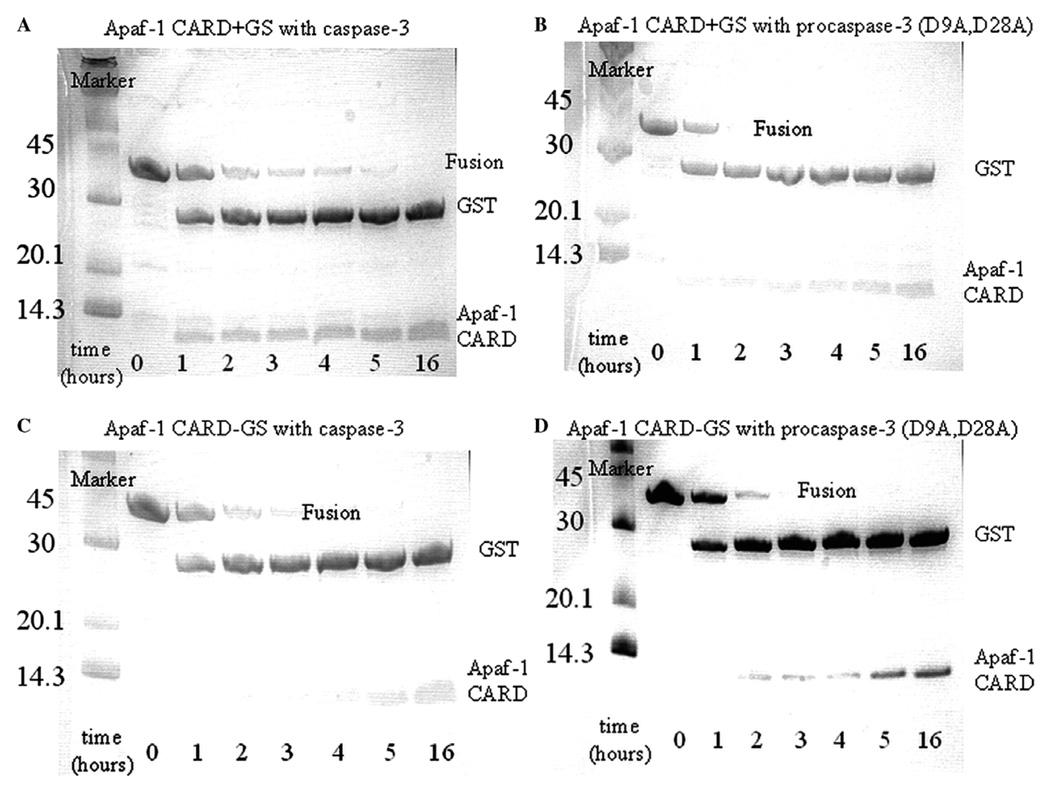

We then processed Apaf-1 CARD + GS and Apaf-1 CARD − GS fusion proteins with caspase-3 or procaspase- 3 (D9A, D28A) at 1:1, 1:0.1, and 1:0.01 (wt:wt) concentrations (fusion protein:protease). The 1:0.01 samples are shown in Fig. 3 for the caspase enzymes. The data show that the fusion proteins were processed completely within 5 h with wild-type caspase-3 (Figs. 3A and C) and within 3 h with procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A) (Figs. 3B and D). This shows that approximately 0.01 mg of caspase-3 can completely cleave 1mg of fusion protein within 5 h at 25 °C. When compared to the thrombin protease (compare Figs. 2 and 3), these data demonstrate that caspase-3 and procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A) cleave the fusion protein with approximately 400-fold greater efficacy than thrombin protease. In addition, procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A) is slightly more efficient than the wild-type enzyme, consistent with our studies that have shown the activity of this variant to be about 25% higher than that of the wild-type protein [22].

Fig. 3.

Limited proteolysis with caspase-3 and procaspase-3(D9A, D28A). Apaf-1 CARD + GS (1 mg) was incubated with wild-type caspase-3 (A) or procaspase-3(D9A, D28A) (B). Apaf-1 CARD − GS (1mg) was incubated with wild-type caspase-3 (C) or procaspase-3(D9A, D28A) (D). Samples were removed at each time point and analyzed as described in Materials and methods. For (A) through (D), the amount of caspase (wild-type or mutant) used for each reaction was 0.01 mg. Sizes (in kilodalton) of molecular weight markers are shown next to each marker.

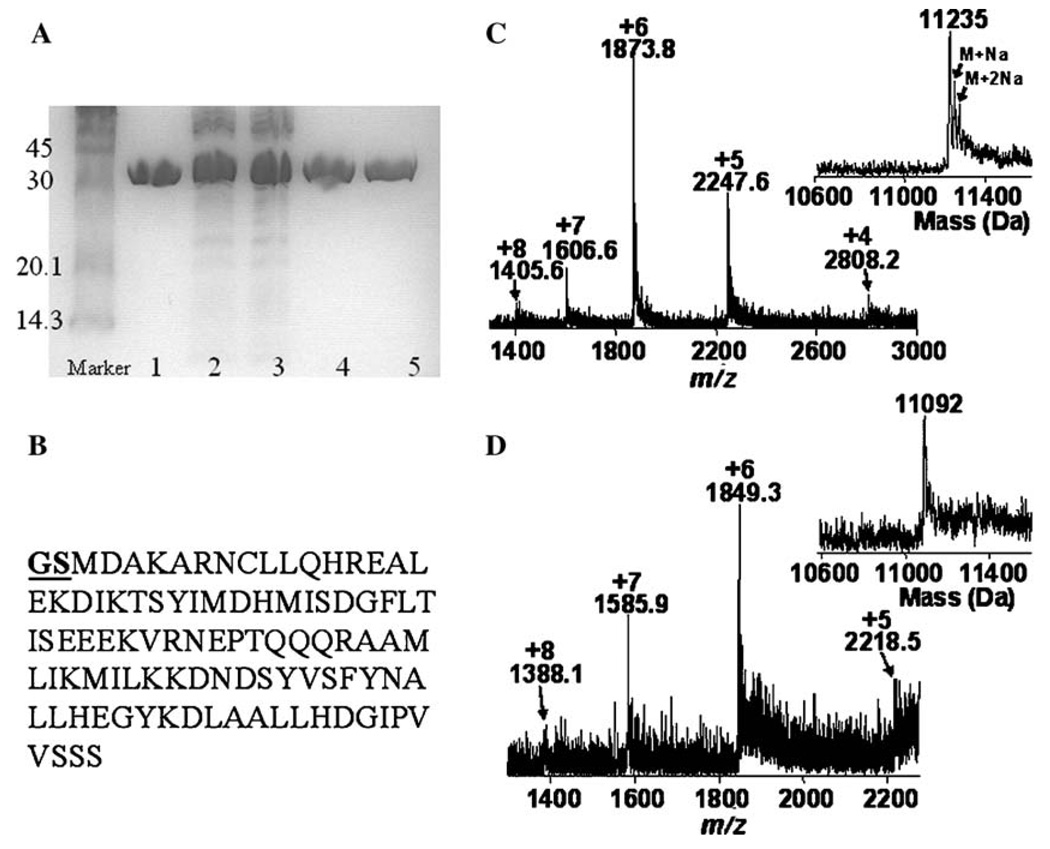

To study the cross-reactivity of the proteases, we incubated Apaf-1 CARD + GS (1mg) or Apaf-1 CARD − GS with thrombin (1mg or 10U), and we incubated Apaf-1 CARD-2T (1mg) with caspase-3 (0.1mg) or procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A) (0.1mg). As shown in Fig. 4A, thrombin did not cleave Apaf-1 CARD + GS or Apaf-1 CARD − GS. Likewise, neither caspase-3 enzyme cleaved Apaf-1 CARD-2T, even after prolonged incubation times (24 h) and at concentrations 10 fold higher than those shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Specific caspase cleavage of Apaf-1 CARD fusion proteins. (A) Control for non-specific cleavage by thrombin, caspase-3, or procaspase-3(D9A, D28A). Lane 1, Apaf-1 CARD + GS (1 mg) without protease; lane 2, Apaf-1 CARD + GS (1 mg) incubated with thrombin (1mg); lane 3, Apaf-1 CARD − GS (1mg) incubated with thrombin (1mg); lane 4, Apaf-1 CARD-2T (1 mg) incubated with caspase-3 (0.1mg); lane 5, Apaf-1 CARD-2T (1mg) incubated with procaspase-3(D9A, D28A) (0.1 mg). All samples were incubated for approximately 24 h at 25 °C and then were analyzed as described in Materials and methods. Sizes (in kilodalton) of molecular weight markers are shown next to each band. (B) Amino acid sequence of Apaf-1 CARD + GS. (C and D) Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI–MS) analysis of Apaf-1 CARD + GS and Apaf-1 CARD − GS cleavage products after removal of the GST tag. The ESI–MS spectra of (C) Apaf-1 CARD + GS and (D) Apaf-1 CARD − GS as well as the corresponding deconvoluted mass spectra (insets) are shown. The difference in the average mass (143Da) between Apaf-1 CARD + GS (11,235 ± 8Da measured, 11,228Da theoretical) and Apaf-1 CARD − GS (11,092 ± 8Da measured, 11,084Da theoretical) is consistent with the calculated mass for a GS deletion (144Da) using the extended m/z range on the ion trap. For (C), the two minor peaks present in the deconvoluted mass spectrum are adducts of Apaf-1 CARD + GS containing either one (M+Na) or two (M+2Na) sodium ions.

To confirm caspase protease cleavage of the fusion protein at the proper location with no additional cleavages or residual amino acids, we performed electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis with the purified Apaf-1 CARD proteins (Figs. 4C and D). The results show that both of the measured masses the Apaf-1 CARD + GS and Apaf-1 CARD − GS proteins (11,235 and 11,092 Da, respectively) were within the experimental error range at high mass calibration (0.07%) of the theoretical average mass for each protein (11,228 and 11,084 Da, respectively). The masses of the target protein for each construct were the same regardless of whether caspase-3 or procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A) was used in the cleavage reaction.

Discussion

The caspase-3 protease system provides an opportunity to obtain all the benefits provided by N-terminal fusion proteins while eliminating unwanted amino acids on the amino-terminus of the protein of interest. To provide a more stable protease for fusion protein cleavage, we engineered the caspase-3 enzyme to retain full activity for at least 72 h at 25 °C, although the enzyme requires only 3–5 h to cleave the fusion protein under the conditions presented here. Because the caspase-3 enzymes include C-terminal poly-histidine tags, they are easily separated from the target protein by binding to an affinity resin, such as Ni2+–Sepharose. Following purification in this manner, there was no detectable caspase-3 enzyme activity in the purified Apaf-1 CARD used in these studies (data not shown). Other properties of the caspase-3 enzyme that make it appealing for use as a protease in a purification system are its wide range of salt tolerance [22], high specificity (specificity constant of 2 × 105 M−1 s−1, where specificity constant is defined as kcat/Km) [14,15], and efficient cleavage of substrate. Caspase-3 is most active at pH 7.5, although it functions from pH ~5.5 to pH ~10 [14,16].

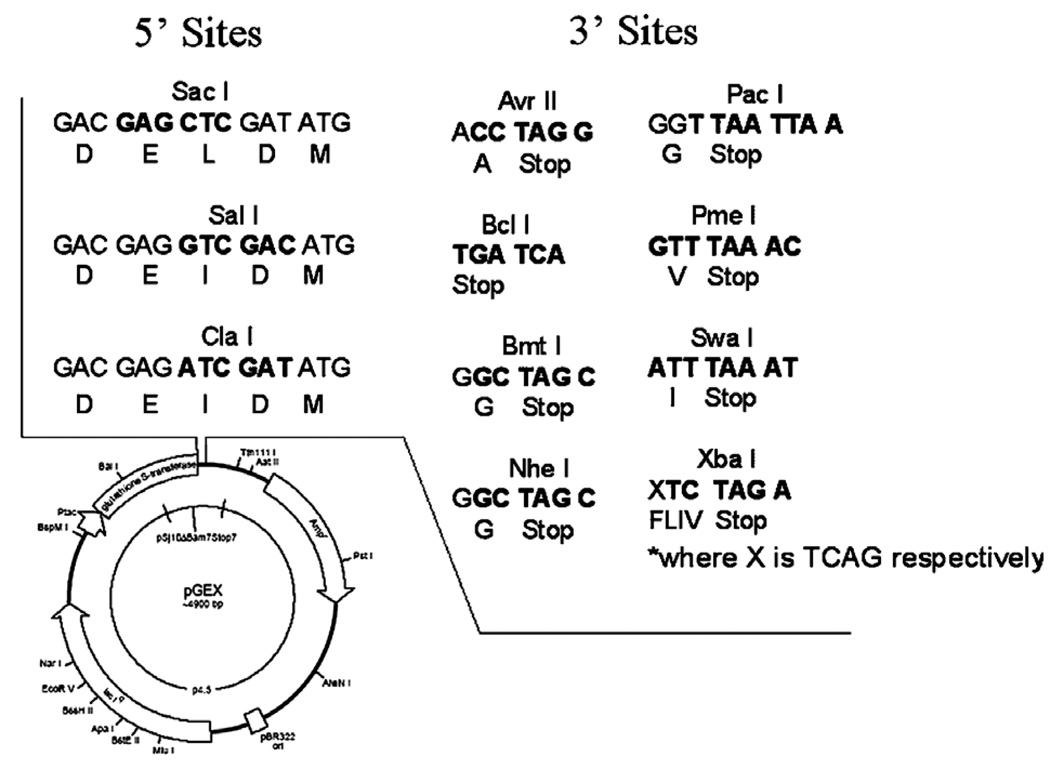

To increase the capabilities of this system, we have designed potential cloning sites compatible with the DXXD motif that may facilitate the sub-cloning of genes into the vector. We present three different sites at the 5′ end of the gene that enable one to clone with no additional N-terminal residues (Fig. 5). In addition, there are eight different possibilities for cloning sites at the 3′ end; one with no additional amino acids (Bcl I), three with glycine (Pac I, Bmt I, Nhe I), one with alanine (Avr II), and three that leave a single hydrophobic amino acid (F/L/I/V) (Xba I). Other cloning sites may be incorporated at the 3′ end of the gene depending on preference of enzyme usage and whether one cares to incorporate a stop codon upstream of the 3′ cloning site.

Fig. 5.

Proposed constructs that employ caspase-3 cleavage sites. A number of unique restriction sites may be incorporated into GST fusion vectors to employ a caspase-3 cleavage site (DXXD) in the fusion protein. Those shown at the 5′ end of the gene leave no additional amino acids on the target protein. It should be noted that many other 5′ or 3′ sites may be used if one would like to exploit the cleavage capabilities of caspase-3 and is not concerned about overhangs.

Overall, the ease of production coupled with the enzymatic and physical properties of caspase-3, as well as those of the more stable procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A), make this purification system an appealing alternative to commercially available systems. In addition, other group III caspases, such as caspase-2 and -7, may be used with the present cleavage recognition site [17,18]. We note that other caspase proteins may be used as an alternative to caspase-3 if one determines that the aspartate in the P4 subsite (DXXD) results in a cleavage site in the target protein. For example, group II caspases, caspase-6, -8, -9, and -10 have a preference for branched apolar residues in the P4 position, whereas group I caspases, caspase-1, -4, and -5 have a preference for aromatic amino acids in the P4 position [17,18]. It is conceivable that mutations similar to those described here in procaspase-3 (D9A, D28A) may be made in any of the other 13 caspases, creating a myriad of protein purification systems that exploit the properties of caspase enzymes.

While we generated and tested the system with a GST tag as a carrier protein, in principle it will work with other available tags. For example, neither bacterioferritin nor E. coli MBP contain DXXD motifs. In contrast, GrpE, NusA, and thioredoxin do contain potential cleavage sites, although an analysis of the structures of GrpE [19] and thioredoxin [20] reveal that the DXXD sequences are present in well-defined α-helical secondary structures and are likely not accessible to the caspase-3 protease active site. Currently, no structural information is available for E. coli NusA, and the DXXD sequence, located at the C-terminus of the protein, is not conserved in Thermotoga maritima NusA, for which the structure has been determined [21].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM065970). A plasmid used for cloning Apaf-1 CARD into pGEX-2T was kindly provided by Leemor Joshua-Tor (Cold Spring Harbor Lab, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, USA). The authors would like to thank the research agencies of North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service for continued support of biological mass spectrometry research and development.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: GST, glutathione S-transferase; MBP, maltosebinding protein; TEV, tobacco etch virus; ESI, electrospray ionization.

References

- 1.Ford CF, Suominen I, Glatz CE. Fusion tail for the recovery and purification of recombinant proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 1991;2:95–107. doi: 10.1016/1046-5928(91)90057-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith DB, Johnson KS. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.di Guan C, Li P, Riggs PD, Inouye H. Vectors that facilitate the expression and purification of foreign peptides in Escherichia coli by fusion to maltose-binding protein. Gene. 1988;67:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaVallie ER, DiBlasio EA, Kovacic S, Grant KL, Schendel PF, McKoy JMA. A thioredoxin gene fusion expression system that circumvents inclusion body formation in E. coli cytoplasm. Biotechnology. 1993;11:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nbt0293-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis GD, Elisee C, Newham DM, Harrison RG. New fusion protein systems designed to give soluble expression in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1999;65:382–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maina CV, Riggs PD, Grandea AG, III, Slatko BE, Moran LS, Tagliamonte JA, McReynolds LA, di Guan C. An Escherichia coli vector to express and purify foreign proteins by fusion to and separation from maltose-binding protein. Gene. 1988;74:365–373. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butt TR, Jonnalagadda S, Monia BP, Sternberg EJ, Marsh JA, Stadel JM, Ecker DJ, Crooke ST. Ubiquitin fusion augments the yield of cloned gene products in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:2540–2544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacquet A, Daminet V, Haumont M, Garcia L, Chaudoir S, Bollen A, Biemans R. Expression of a recombinant Toxoplasma gondii ROP2 fragment as a fusion protein in bacteria circumvents insolubility and proteolytic degradation. Protein Expr. Purif. 1999;17:392–400. doi: 10.1006/prep.1999.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapust RB, Waugh DS. Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein is uncommonly effective at promoting the solubility of polypeptides to which it is fused. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1668–1674. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.8.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutz R, Bujard H. Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichia coli via the LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I1–I2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens RC. Design of high-throughput methods of protein production for structural biology. Structure. 2000;8:R177–R185. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shih Y-P, Wu H-C, Hu S-M, Wang T-F, Wang AH-J. Self-cleavage of fusion protein in vivo using TEV protease to yield native protein. Protein Sci. 2005;14:936–941. doi: 10.1110/ps.041129605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pop C, Chen Y-R, Smith B, Bose K, Bobay B, Tripathy A, Franzen S, Clark AC. Removal of the pro-domain does not affect the conformation of the procaspase-3 dimer. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14224–14235. doi: 10.1021/bi011037e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bose K, Pop C, Feeney B, Clark AC. An uncleavable procaspase-3 mutant has a lower catalytic efficiency but an active site similar to that of mature caspase-3. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12298–12310. doi: 10.1021/bi034998x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stennicke HR, Renatus M, Meldal M, Salvesen GS. Internally quenched fluorescent peptide substrates disclose the subsite preferences of human caspases 1, 3, 6, 7 and 8. Biochem. J. 2000;350:563–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS. Biochemical characteristics of caspases-3, -6, -7, and -8. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25719–25723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thornberry NA, Rano TA, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Timkey T, Carcia-Calvo M, Hotzager VM, Nordstrom PA, Roy S, Vaillancourt JP, Chapman KT, Nicholson DW. A combinatorial approach defines specificities of members of the caspase family and granzyme B. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17907–17911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Calvo M, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Vaillancourt JP, Zamboni R, Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. Purification and catalytic properties of human caspase family members. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:362–369. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison CJ, Hayer-Hartl M, Di Liberto M, Hartl F-U, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the nucleotide exchange factor GrpE bound to the ATPase domain of the molecular chaperone DnaK. Science. 1997;276:431–435. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5311.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmgren A, Soderberg B-O, Eklund H, Branden C-I. Three-dimensional structure of Escherichia coli thioredoxin-S2 to 2.8 Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:2305–2309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.6.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin DH, Nguyen HH, Jancarik J, Yokota H, Kim R, Kim S-H. Crystal structure of NusA from Thermotoga maritima and functional implication of the N-terminal domain. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13429–13437. doi: 10.1021/bi035118h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feeney B, Clay A. Clark, Reassembly of active caspase-3 is facilitated by the propeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505834200. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]