Abstract

Genes involved in human male sex determination and spermatogenesis are likely to be located on the Y chromosome. In an effort to identify Y-linked, testis-expressed genes, a cDNA selection library was generated by selecting testis cDNA with Y-cosmid clones. Resultant clones containing repetitive or vector material were eliminated, and 79 of the remaining clones were sequenced. Nineteen cDNAs showed homology with the TTY2 gene, and indicated that TTY2 is part of a large gene family. Screening of a panel of Y-linked cosmids revealed that the TTY2 gene family includes at least 26 members organized in 14 subfamilies. Further investigation revealed that TTY2 genes are arranged in tandemly arrayed clusters on both arms of the Y chromosome, and each gene comprises a series of tandemly arranged repeats. RT-PCR studies for two of these genes revealed that they are expressed in adult and fetal testis, as well as in the adult kidney. None of the genes investigated in detail contain an open reading frame. We conclude that the TTY2 gene family is composed of multiple copies, some of which may function as noncoding RNA transcripts and some may be pseudogenes.

[The sequence data described in this paper for TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A have been submitted to the EMBL data library, under accession nos. AJ297963 and AJ297964.]

The mammalian Y chromosome is small, ∼59 Mb, carries an estimated 100 genes, and is composed mainly of repeated sequences (Cooke 1976; Goodfellow et al. 1985; Smith-Ferguson et al. 1987; Vogt et al. 1997). Y-linked genes are of particular interest, because they provide information about the origin of the Y chromosome and its function in sex determination and differentiation. Several genes involved in the process of spermatogenesis have been located on the Y, including the DAZ, TSPY, and RBMY gene families (Arnemann et al. 1987; Ma et al. 1993; Reijo et al. 1995), and the single-copy SRY gene, which is considered to be the testis determining factor (TDF) (Sinclair et al. 1990). Deletions of one or more of these genes can lead to infertile and subfertile male phenotypes (Tiepolo and Zuffardi 1976; Ma et al. 1992; Rejio et al. 1995; Schnieders et al. 1996; Vogt et al. 1996; Pryor et al. 1997; Ferlin et al. 1999).

To date, only 47 Y-linked genes and pseudogenes have been identified (GDB database, http://gdbwww.gdb.org). Because not all cases of idiopathic infertility can be explained by loss of known Y-linked or autosomal genes, it seems likely that other Y-linked genes with a role in male fertility remain to be discovered.

To identify novel Y-linked genes we constructed a “Y-specific–testis-expressed” cDNA library, using the technique of direct selection (Lovett et al. 1991; Lovett 1994; Del Mastro and Lovett 1997). We used a panel of Y-linked cosmids as a genomic target and human testis mRNA as the hybridization partner. In this paper, we describe the analysis of cDNA clones isolated from this “Y-specific–testis-expressed” cDNA selection library and the identification of a Y-linked multicopy gene family, TTY2.

RESULTS

cDNA Selection Library Evaluation

The cDNA selection procedure was carried out using first-strand cDNA, prepared from adult human testis RNA and DNA from 960 cosmid clones, derived from two different Y chromosome-specific libraries (Taylor et al. 1996) as the genomic target. Four thousand, six hundred and eight recombinant clones were selected and arrayed in 48 96-well microtiter plates.

Because previous experience (Cheng et al. 1994; Simmons et al. 1995, 1997; Guimera et al. 1997; Touchman et al. 1997) has shown that cDNA selection libraries are prone to contamination with vector sequences, it was decided to screen these arrays with probes specific for the cosmid vectors Lawrist B and Lawrist 16. The library was also screened with probes containing the Y-specific repeat sequence, DYZ1 (Cooke 1976); these were a PCR product containing the DYZ1 sequence and DNA from the OXEN (49,XYYYY,) cell line. The extent of positive hybridization signals obtained with these probes indicated that the proportion of recombinants containing either vector or repeat sequences was unexpectedly high, around 80%. However, 731 clones did not hybridize to either vector or repeat sequences, and were regarded as bona fide cDNAs for further analysis.

Sequence from 79 of these cDNAs was determined and compared to current sequence databases. A large proportion (49.4%) of the expressed sequences matched (>95% identity) to known Y-linked genes and ESTs (Table 1a); 30.4% of the analyzed cDNAs were expressed in testis or testis-related tissues (Table 1b); 28.4% of the clones showed homology to sequences located on autosomes or the X chromosome and to ESTs from cDNA libraries generated from tissue other than testis; 7.6% of the sequences did not identify any matches in current databases. Details of all these sequences can be found at http://www.gene.ucl.ac.uk/users/eleni/index.htm.

Table 1.

Homology of cDNA Clones

| Table 1a | ||

| No. of cDNA clones | cDNA/gene | ESTs |

| 1 | RBMY2 | |

| 6 | TSPY | |

| 19 | TTY2 | AI016094, AI147341, AA620621 |

| 6 | AW291677, AA195274 | |

| 3 | AW162304, AL110434 | |

| 3 | AW205403, AI651385 | |

| 1 | AW016837, AW70214 | |

| Total: 39 | ||

| Table 1b | ||

| No. of cDNA clones | cDNA/gene | ESTs |

| 1 | RBMY2 | |

| 6 | TSPY | |

| 1 | c-myc gene | AI684722 (testis) |

| 3 | AL110434 (testis) | |

| 3 | AW205403 (germ cell), AI651385 (germ cell tumors) | |

| 6 | AW291677 (germ cell) | |

| 1 | AI865741 (prostate) | |

| 1 | AL039930 (testis) | |

| 1 | AI989707 (germ cell tumors) | |

| 1 | Nuclear | AI695810 (prostate), AI205797 |

| aconitase | (testis) | |

| Total: 24 |

cDNA clones that show >95% identity with (a) Y-linked expressed sequences and (b) expressed sequences from testis and testis-related tissues.

Identification and Chromosome Mapping of TTY2 Homologous Genes

Nineteen cDNAs showed ∼65–78% similarity to TTY2 (testis specific Y linked), a testis-specific mRNA of ∼3.2 kb described by Lahn and Page (1997). None were identical to the published TTY2 sequence. Of the 19 TTY2-like clones, 16 overlapped in sequence and comprised a single sequence, designated TTY2L2A, after one of the cDNAs in this group. The remaining three TTY2-like sequences (TTY2L12A, TTY2L14, and TTY2L15) were distinct from TTY2, TTY2L2A, and each other, suggesting that these sequences represent distinct members of a Y-linked gene family.

To facilitate detailed chromosome mapping of TTY2L2A and TTY2L12A, genomic clones corresponding to each cDNA were identified in a two-step procedure. An array of 500 Y-linked cosmids was hybridized to α-32P dCTP-labeled TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A cDNA probes, each of which identified the same 34 cosmids. DNA from this set of TTY2-like cosmids was then PCR amplified using primers specific for TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A. This identified two cosmids, Yco2E9 and Yco2F6, corresponding to TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A, respectively. DNAs from Yco2E9 and Yco2F6 were used as probes to determine their chromosomal localization by FISH analysis of human metaphase chromosome spreads (Fig. 1a). This showed that Yco2E9 (TTY2L12A) is located in the distal part of Yp, whereas Yco2f6 (TTY2L2A) is located on Yq. It was notable that a very strong FISH signal was seen in both cases, which was interpreted as indicating the presence of a cluster of related sequences.

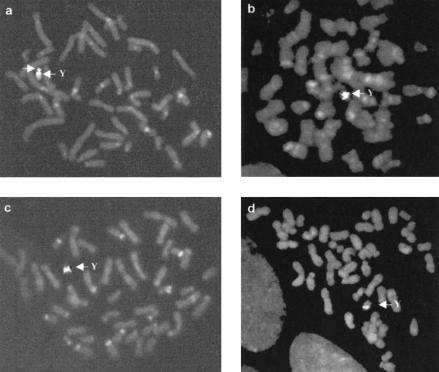

Figure 1.

Double fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) to human (a), chimpanzee (b), pigmy chimpanzee (c), and gorilla (d) metaphase chromosomes, using the cosmids 2E9 (TTY2L2A) and 2F6 (TTY2L12A) as probes. Specific signal in all species is seen only on the Y chromosome. The centromeric and banded signals are due to DAPI staining, and would appear as blue signal in a colored photograph.

When the same probes were used on metaphase spreads from a male chimpanzee, a pigmy chimpanzee, and a gorilla, it was found that TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A sequences are present at distinct locations on the short and long arm of Chr Y as in humans (Fig. 1b,c,d). In no case were signals detected on the X chromosome or on autosomes.

To define the regional localization more accurately, YACs, which form a tiling path across the human Y chromosome (described in Jones et al. 1994), were individually amplified using the TTY2L12A and the TTY2L2A specific primers. In both cases, a product of the correct size and sequence was amplified from a single YAC, indicating that TTY2L12A lies on YAC 759G2 and TTY2L2A on YAC 933A6.

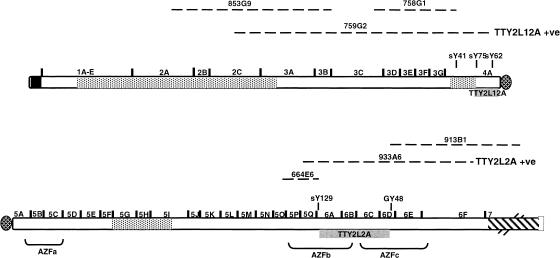

YAC 759G2 (TTY2L12A) has been localized to the Yp11.31–11.2 region (Jones et al. 1994), and covers part of the subinterval 2C, the whole of 3A to 3G, and most of interval 4A close to the centromere (as defined by Vergnaud et al. 1986; Vollrath et al. 1992). However, the part that would cover intervals 3C–3G is known to be deleted in this YAC (Jones et al. 1994). YAC 759G2 overlaps with YAC 853G9 and YAC 758G1, neither of which gave amplification products with primers specific for TTY2L12A; thus, the most likely location for the TTY2L12A sequence is within interval 4A between the STS markers sY75 and sY62 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Localization of TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A on the Y chromosome. Broken lines indicate position of YACs spanning the euchromatic and part of the heterochromatic region (Jones et al. 1994). TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A were positioned by PCR amplification of these YACs. Y chromosome intervals (as defined by Vergnaud et al. 1986; Vollrath et al. 1992) are indicated together with several Y- linked STSs (shown slightly elevated).

YAC 933A6 (TTY2L2A) has been localized to Yq11.2 (Jones et al. 1994), and covers the AZFb region and part of the AZFc region, from the 5Q subinterval across the whole of interval 6 (6A–6F). PCR amplification showed that TTY2L2A is not present on overlapping YACs 664E6 and 913B1; thus, it seems that it is located in the proximal 6 interval (6A, 6B, 6C, and part of 6D), either within the AZFb or AZFc regions (Fig. 2).

Expression Studies

The expression patterns of TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A were examined by RT-PCR using RNA prepared from a panel of human adult and fetal (11.5- and 16.5-wk gestation) tissues. Prior to RNA preparation, all tissues were male sex determined by PCR amplification of DNA, using primers that amplify the X- and Y-linked homologs of amelogenin, to give products of different sizes (432 bp X; 252 bp Y). Males (XY) show two distinct amelogenin PCR products, and females (XX) a single product (Pertl et al. 1996).

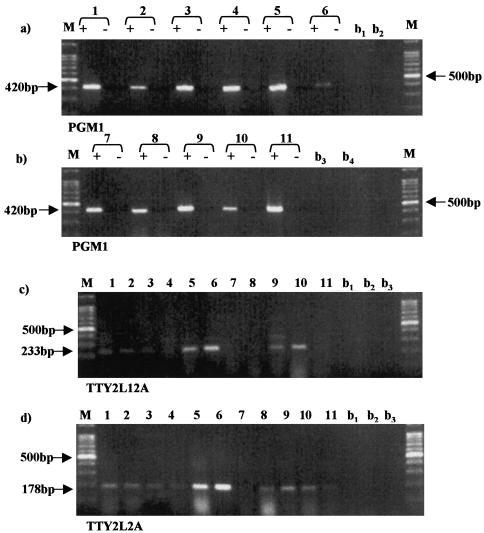

RT-PCR, with primers specific for TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A, showed a similar expression pattern. For both cDNAs there was only trace expression in fetal kidney and limbs, moderate to weak expression in all other tissues, including adult and fetal testis, and high levels in adult kidney, fetal lung, and in the case of TTY2L12A, fetal intestine (Fig. 3c,d). These results confirm that both TTY2-like RNAs are expressed in developing and adult testis, but it is also clear that testis is not the major site of expression. Because TTY2 has been described as a testis-specific RNA, it was important to establish that the TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A PCR products detected in nontestis tissue were identical to that found in testis. PCR products from three tissues, adult testis and kidney, and fetal lung, were sequenced and found to be identical to that in testis. Thus, both genes are expressed in a nontissue-specific manner.

Figure 3.

PCR amplification of tissue cDNA, using PGM1 primers (a and b) and primers specific for TTY2L12A (c) and TTY2L2A (d); the samples are as follows: 1, adult testis; 2, fetal testis; 3, adult prostate; 4, fetal brain; 5, fetal lung; 6, adult kidney; 7, fetal kidney; 8, fetal heart; 9, fetal stomach; 10, fetal intestine; 11, fetal limbs. M, DNA size marker; b1–4, PCRs without cDNA. cDNA synthesis was carried out in presence (+) and absence (−) of reverse transcriptase.

The TTY2 Gene Family

The 34 cosmids containing TTY2-like sequences identified by homology to TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A were analyzed in more detail. In the first instance, a sequence common to TTY2L12A and TTY2 was identified by alignment of their sequences. Using this information, TTY2 primers common to both sequences were designed and used to amplify DNA from all 34 TTY2-like cosmids. All cosmids in this set gave a product of ∼300 bp, and sequence analysis showed that these sequences segregated into 24 distinct TTY2-like sequences. When aligned using the CLUSTALX program, these could be grouped into 14 classes, or subfamilies. Each subfamily contained one to five members, which share 93%–99% identity. Members of different subfamilies have diverged more significantly, and share 55%–87% identity (data available at http://www.gene.ucl.ac.uk/users/eleni/index.htm). This large number of distinct sequences suggested that the TTY2 gene family is extensive.

A view of the order of duplications that took place during the evolution of this complex gene family was provided from phylogenetic analysis (not shown); this suggested that the TTY2L12A and TTY2 genes are closely related, as are TTY2L1A and TTY2L2A.

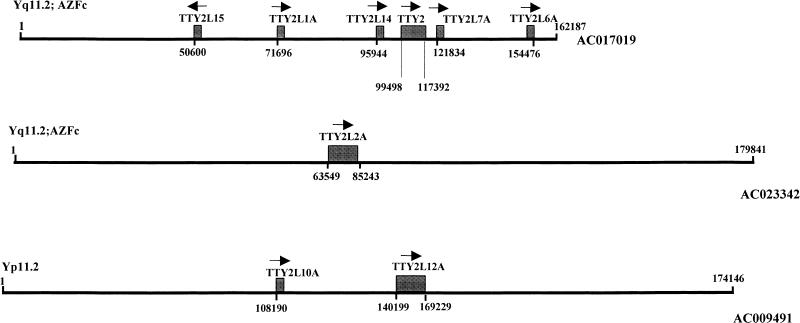

Database searches found 100% identity matches for several of the TTY2-like sequences to large genomic fragments, mainly BACs. In a number of instances more than one TTY2-like sequences appear on the same genomic fragment. Two such sequence clusters were examined in more detail: one that carries the TTY2 cDNA sequence, and another that carries the TTY2L12A cDNA sequence. Six TTY2-like sequences, which include TTY2, the TTY2-like cDNAs TTY2L14 and TTY2L15, and three other TTY2-like sequences (TTY2L1A, TTY2L6A, and TTY2L7A, identified from the Y-cosmids PCRs), lie on a 90-kb contiguous stretch of genomic DNA (AC017019, Genome Sequencing Center, http://genome.wustl.edu/gsc/) (Fig. 4, top). Both TTY2 (Lahn and Page 1997) and TTY2L2A (present study), are known to be at Yq11 within the AZF regions, and Lahn and Page (1997) provided evidence that firmly places TTY2 in the AZFc region, so it can be assumed that the closely linked TTY2-like sequences shown in Figure 4 (top) are also within this region.

Figure 4.

Localization of the TTY2 gene and other members of this gene family on three genomic fragments (AC017019, AC023342, and AC009491); arrows indicate the relative orientation of the genes; numbers below arrows indicate the first bp of identity with the genomic fragment.

A second TTY2-like gene cluster, which includes TTY2L12A and TTY2L10A, lies on the genomic fragment AC009491 (http://genome.wustl.edu/gsc/). These sequences are ∼32 kb apart. From the FISH and YAC mapping it has been established that TTY2L12A, and hence AC009491, lie at Yp11.2 (interval 4A).

Gene Structure for TTY2, TTY2L12A, and TTY2L2A

Although the TTY2 cDNA was described several years ago (Lahn and Page 1997), the structure of the gene remained unknown. However, the availability of the major part of the human genomic sequence in databases allowed us to investigate the gene structure by alignment of the cDNA sequence with the genomic sequence AC017019. Contiguous regions of the TTY2 cDNA matching noncontiguous regions of the genomic clone, representing seven exons with six intervening sequences distributed across 17.9 kb (Table 2). Each exon/intron boundary coincides correctly with the appropriate donor/acceptor splice site sequences and intronic polypyrimidine tracts. Exon sizes varied between 79 bp and 1.8 kb, and intron sizes between 120 bp and 7.4 kb.

Table 2.

Genomic Structure of the TTY2, TTY2L12A, and TTY2L2A Genes

| TTY2 | |||

| Exon | 3′ sequence | Intron sequence | 5′ sequence of next exon |

|---|---|---|---|

| exon 1 (1818 bp) | AAAATGCATTGT | gtgagtattt... (2474 bp) ...ccttttgcag | AGAGGCCCTGCA |

| exon 2 (87 bp) | CTGGGTTCTCAG | gtaagttcct... (7394 bp) ...ttttttttag | GCTGGCTGACAG |

| exon 3 (149bp) | AACTCCGTGGAG | gtgagtcagc... (692 bp) ...tgtctttcag | CCAATCCAAGGA |

| exon 4 (157 bp) | AACAGCAATAAG | gtaataaggt... (2830 bp) ...attggcgtag | TTTCCTTGGTCT |

| exon 5 (79 bp) | GGATTCTATTGT | gtgagtattt... (120 bp) ...acttctatag | AAAAGCTGCATG |

| exon 6 (198bp) | AGCAGCAATAAG | gtaagatgcg... (1223 bp) ...ttcctttcag | GCTGGGTCCACA |

| exon 7 (683 bp) | TGACAAGTCCCT | gtggattgag... | |

| TTY2L12A | |||

| Exon | 3′ sequence | Intron sequence | 5′ sequence of next exon |

| exon 1 (1914 bp) | GGTATCCATTGC | ataagtgttt... (10678 bp) ...cctttcccag | AGAAACCCTGTG |

| exon 2 (86 bp) | CTGGGGTCTCAG | atatgattct... (281 bp ) ...ctctgcttag | ACAGGCTGACAG |

| exon 3 (165bp) | AACACCATGGAG | gtgggttggt... (679 bp ) ...tgtccttcag | CCAAGCCAGGGA |

| exon 4 (157 bp) | AGGAGCAATGAG | gacagatagg... (2721 bp ) ...cgacataggg | TTTCCTGGATCT |

| exon 5 (79 bp) | GGAATCTATTGT | gtgagtgttt... (1775 bp ) ...agcacaacaa | AACAAAAAAAAC |

| exon 6 (191bp) | AGCAGCAATAAG | atcagattgg... (7082 bp ) ...ttgctttcat | CAGGAATCTACT |

| exon 7 (662 bp) | GTTGCCAAGAGA | caagtccctg... | |

| TTY2L2A | |||

| Exon | 3′ sequence | Intron sequence | 5′ sequence of next exon |

| exon 1 (1951 bp) | GGAATCCATTGT | gtgagtgttt... (3113 bp) ...cctttcctag | AGAGCCCCTGTG |

| exon 2 (87 bp) | CTGGGGTCTCAG | gtatgattct... (2424 bp) ...ctctgcttag | GTAGGGTGACAG |

| exon 3 (168 bp) | ATTTCCATGAAA | gtgtgttggt... (5581 bp) ...tttcctgtgg | CCAACCCACAGA |

| exon 4 (157 bp) | AACAAGTCAGAT | gagtgaagat... (2085 bp) ...cggcctaggg | CTTCCTGGGTCT |

| exon 5 (79 bp) | GGAATCCAATGC | atgagtgttt... (1859 bp) ...accacaccaa | AAAACAGACATC |

| exon 6 (191 bp) | GCAGGGAGAAAT | tcagatatgg... (3332 bp) ...tggctttcat | GGGGGATTCACA |

| exon 7 (677 bp) | TGCCACCTTTGC | ctagtgacaa... |

Structure is derived by alignment of the cDNA with genomic DNA sequence from AC017019, AC009491, and AC023342, respectively. DNA sequences at exon/intron junctions are shown. Exon sequences are shown in upper case. Intron sequence is shown in lower case. The sizes of each exon and intron are given in parentheses.

The gene structure for the TTY2 gene was used to predict structures for the TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A genes. The BESTFIT (HGMP, GCG package) alignment program was used to identify exons in the DNA fragments with accession nos. AC009491 (TTY2L12A) and AC023342 (TTY2L2A) by homology to TTY2. In both cases, seven exons were identified (Table 2), each showing 72–82% identity with the TTY2 exons. The predicted TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A genes are longer than the TTY2 gene, spanning 29 kb and 26.5 kb, respectively. This size difference is largely due to variation in the sizes of introns 1, 5, and 6. In addition to these differences, both TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A show ∼10 small exonic deletions and insertions relative to TTY2. The predicted TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A gene structures do not entirely conform with the AG–GT exon/intron boundary rule. The intron sequence at the splice sites for intron 1 and intron 2 are conserved in TTY2L2A, while only the sequence at the splice site of intron 3 is conserved in TTY2L12A. However, the exon sequences adjacent to the intron boundaries in each of these cases show some conservation. As described for TTY2, neither TTY2L12A nor TTY2L2A show significant open reading frames, and their sequences do not match known expressed genes in the databases.

An Internally Repeated Structure, Characteristic of TTY2-Like Genes

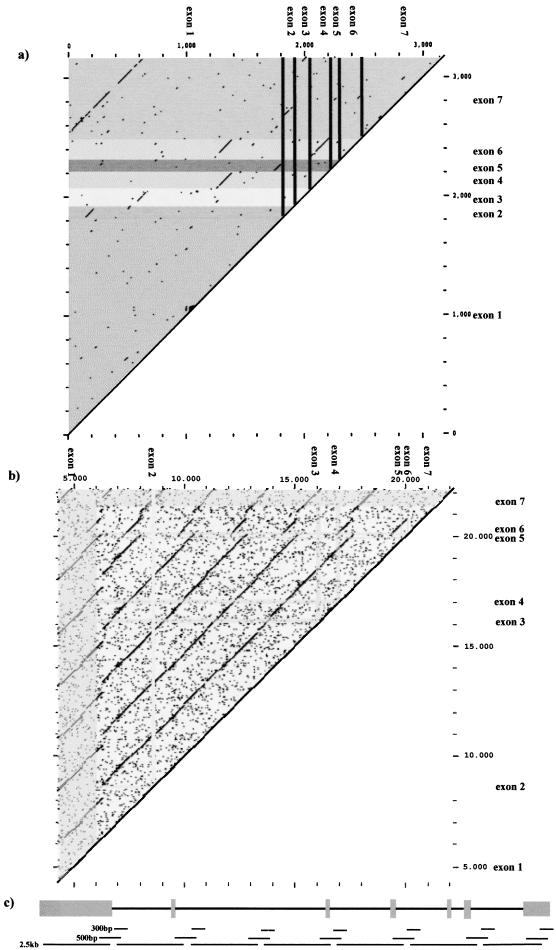

Alignment of the TTY2 and TTY2-like cDNAs revealed the presence of repeated sequences. DOTPLOT analysis and other sequence alignment programs demonstrated that exons 2–7 are repeated within the large exon 1 (1818 bp), with 70–75% homology. In addition, exon 6 and exon 4 share 73% identity, and exon 7 and exon 2 share 65% identity. Figure 5a shows the DOTPLOT analysis of the TTY2 cDNA sequence to itself. Very similar results were obtained from comparison of the TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A cDNAs to themselves (not shown). To establish whether this repeat structure was a particular feature of the cDNA or represented a larger repeat of genomic DNA, DOTPLOT comparisons of each genomic sequence (TTY2, TTY2L12A, and TTY2L2A) to themselves were done. These comparisons demonstrated that each gene comprises seven tandemly arranged repeats of ∼2.4 kb, together with less frequent repeat units of 0.3 kb and 0.5 kb. Figure 5b shows a DOTPLOT analysis of the TTY2 genomic sequence, and again, very similar results were obtained for TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A. For all three genes, each 2.4 kb repeat shows 75% similarity to any other repeat.

Figure 5.

DOTPLOT analysis of (a) the TTY2 cDNA (3169 bp) to itself, and (b) TTY2 genomic DNA to itself; internal repeats appear as lines off the diagonal. For example in (a), the repeat of exon 7 sequence within exon 1 is clearly seen, and in (b) the tandem repeats of ∼2.4 kb are obvious. For clarity, a line drawing of the repeat elements within the gene is shown in (c).

DISCUSSION

In 1997, Lahn and Page described a Y-linked, testis-specific cDNA, which they designated TTY2. The TTY2 gene was more accurately located on the Y chromosome by PCR amplification of DNA from males carrying partial Y chromosome deletions (Vollrath et al. 1992) and by PCR amplification of YACs spanning the Y chromosome euchromatic region (Foote et al. 1992). These studies defined two localizations of TTY2 on the Y chromosome: Yp11.2 within 3G and 4A, and Yq11.2 within 6C. It was noted by Lahn and Page (1997) that this cDNA identified multiple hybridizing bands on Southern blots.

The TTY2 Gene Family

In the present study we have shown that TTY2 exists on the Y chromosome as an extensive gene family, with 26 copies, that can be grouped on the basis of their sequence similarities into at least 14 subfamilies. The level of identity among members of the same subfamily is ∼93%–99%, and between different subfamilies ∼55–87%. This pattern of similarity implies a multistage evolution, in which one wave of duplications gave rise to the subfamily founder member, and a subsequent series of duplications led to expansion of some families. Transposition of individual genes and groups of genes resulted in clusters of TTY2 genes at various positions on the Y chromosome.

There is evidence that gene translocation has been a relatively common event in the history of the TTY2 genes; at least two clusters of genes occur: a large group on Yq (AZFc), and a smaller one on Yp. The gene multiplicity and clustering shown by the TTY2 family is a feature shared with other male-specific, Y-linked gene families, such as RBMY (Chai et al. 1997), DAZ (Saxena et al. 1996), and TSPY (Manz et al. 1993; Vogel and Schmidke 1998; Ratti et al. 2000), which are also arranged in tandemly arrayed clusters on both arms of the Y chromosome. It is notable that the location of the TTY2-like genes coincides with the location of two TSPY gene clusters in both arms of the Y chromosome (Arnemann et al. 1991; Vogt et al. 1987; Ratti et al. 2000). It has been suggested that the region containing TSPY on Yp is particularly prone to chromosomal rearrangements, and contains many tandemly repeated sequences (Müller et al. 1989). It seems reasonable to propose that at some time in the evolutionary past, large genomic segments, which contained both TSPY and TTY2 genes, had been duplicated and translocated between Yq and Yp.

The Function of TTY2 and TTY2-Like Genes

It is difficult to judge at this stage whether any of the TTY2-like sequences represent functional genes. Although TTY2, TTY2L12A, and TTY2L2A lack an open reading frame (ORF), the presence of transcribed RNA in cells of different types has been clearly demonstrated in this paper by RT-PCR, and for TTY2 by Northern blot analysis (Lahn and Page 1997). One possibility is that some or all of the TTY2 copies are pseudogenes. The transition between functioning gene and pseudogene is usually gradual, and in the early stages, the gene may continue to be expressed at the RNA level. Our studies show that TTY2 (Lahn and Page 1997) has exon/intron splicing junctions that conform to the AG–GT rule. However, this rule does not hold at all boundaries in the TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A genes, which could be interpreted as decay of the functional sequence, and perhaps supports the idea that these copies are pseudogenes. It remains to be seen whether other members of this gene family will prove to have consensus intron/exon sequence structure.

Alternatively, the lack of a distinct ORF may imply that members of the TTY2 gene family function at the RNA level rather than encoding a protein product (Eddy 1999; Erdmann et al. 2000). Examples of genes functioning in this way are H19 (Askew et al. 1991), HIS-1 (Hao et al. 1993), and DGCR5 (Sutherland et al. 1996), which, although they lack protein coding capacity, are able to produce large, spliced, and polyadenylated RNAs.

RT-PCR analysis confirmed that TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A genes are expressed in testis as is TTY2, but these TTY2L genes are also expressed at significant levels in lung and kidney. Expression in kidney and in testis is not surprising, because both the reproductive and urinary systems in males are developmentally connected, both arising from the nephros (Carlson 1994; Martineau et al. 1997). Futhermore, there are several genes that play a significant role in sex determination and are expressed in both testis and kidney. One example is WT-1, a zinc finger transcription factor, which is associated with genitourinary malformations and plays an important role in genitourinary development (Pritchard-Jones et al. 1990; Mundlos et al. 1993).

The identification of 16 cDNA clones identical to TTY2L2A indicates that this mRNA is far more abundant in the testis mRNA pool than mRNAs from other members of the TTY2 family. Interestingly, TTY2L2A is located within one of the functionally active AZF regions (AZFb or AZFc) of the Y chromosome, where the functional members of the DAZ, RBMY, and TSPY gene families are located (Cooke and Elliot 1997; Chai et al. 1997; Ratti et al. 2000).

A Gene Comprising Tandem Repeats

Our studies of the genomic structure of the TTY2 family members revealed the presence of an internal repetitive structure, which is characteristic of all genes analyzed (TTY2, TTY2L12A, and TTY2L2A). The major repeat units are 2.4 kb long and tandemly arranged across the gene. It can be concluded that the TTY2 genes have emerged from a series of intragenic duplications. The genomic repeat structure is reflected in duplications of exon sequences within a single gene. The homology between exon 1 and exon 7, which extends over 625 bp, was interpreted by Fatyol et al. (2000) as representing the long terminal repeats (LTR) of a retroposon, and led them to propose that TTY2 is a retrogene. Fatyol et al. (2000) found that the 5′ 1.1-kb segment of TTY2 showed homology (68%) to a novel repetitive element present in high copy number near the centromeres of primate chromosomes. However, as we have shown, the pattern of homologies across the gene is extensive, and can be simply explained by intragenic duplication. Furthermore, we show that the TTY2 family members have an exon/intron structure, and lack a protein coding ORF; thus, they do not have the capacity to code for reverse transcriptase and integrase domains, and seem unlikely to be retroposed sequences (Finnegan 1997; Smit 1999).

Comparative Studies—TTY2 Genes

FISH analysis of primate chromosomes indicate that both TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A sequences have been Y-specific, because humans diverged from gorillas 7 million years ago (Goodman et al. 1998).

The YACs used in the present study for mapping of the TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A genes have been used by Archidiacono et al. (1998) to examine the structure and evolution of primate Y chromosomes. Archidiacono et al. (1998) found that YAC821G7 hybridized to the chimpanzee Y chromosome, at Yq12.1–12.2 and gorilla Y chromosome at Yp11.1–11.2. In this study we showed that TTY2L12A lies on YAC 821G7, and this YAC maps in humans to Yp11.2. Thus, TTY2L12A is located in both humans and gorillas on Yp, whereas in chimpanzees it is on Yq. These results suggest that after the divergence of the human and chimpanzee lineages, ∼3–4 Mya, an internal rearrangement such as a translocation and reinsertion in the chimpanzee ancestor, transferred a genomic fragment bearing the TTY2L12A homolog from Yp to Yq.

Our data imply that, at least with regard to the distribution of the TTY2 sequences, the gorilla Y chromosome structure is closer to humans than to chimpanzees. In this context it is interesting to note that the banding patterns of the human and gorilla Y chromosomes show more resemblance to each other than to that of the chimpanzee (Pearson et al. 1971). In addition, some genes are present on the Y chromosome of gorillas and humans, which are not found in the chimpanzee, for example, the GMGXY12 locus (Lambson et al. 1992). These findings suggest that the Y chromosome of the chimpanzee has undergone significant rearrangement since its divergence from the human lineage. Examples of Y chromosome rearrangements during the evolution of hominoid apes have been demonstrated by comparative FISH studies for other Y-linked genes like RBM and TSPY (Schempp et al. 1995), which show that although these genes remain Y-specific, the number of copies and their location(s) may vary among the different primate species.

METHODS

Construction of the cDNA Selection Library

The selection procedure was carried out using first-strand cDNA prepared from an adult human testis RNA template and 480 cosmids from each of two Y chromosome cosmid libraries (n = 960) as the genomic target. One of the cosmid libraries was prepared in Lawrist 16 by flow sorting Y chromosomes from the somatic cell hybrid J640–51, partially digested with MboI, and was obtained from the Biomedical Sciences Division, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLOYNCO3 ‘M’). The second library was prepared in Lorist B (Taylor et al. 1996), using DNA from the somatic cell hybrid 3E7, which contains the Y chromosome as its only human component. The procedure for selecting testis-specific Y-linked cDNAs was carried in a manner similar to that described by Lovett (1994) and Del Mastro and Lovett (1997). Hybridization reaction was carried out in solution. The target genomic DNA was tagged with biotin 16-UTP by nick translation, and the capture of genomic DNA and the associated cDNAs was performed by streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. Two rounds of cDNA selection were carried out, followed by one round of subtraction with human Cot-1 DNA, to remove highly repetitive sequences. In this way, 4608 cDNAs were selected and amplified in the plasmid pAMP10. The clones were arrayed in 48 96-well microtiter plates in 100 μL of 2× TY agar medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin.

Filter Hybridization

Samples of the plasmid arrays were transferred onto Hybond N+ nylon membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and grown on L-agar plates containing ampicillin, 100 μg/mL, overnight at 37°C. The filters were placed in denaturing solution (1.5 M NaCl and 0.5 M NaOH) for 30 min, neutralized in 1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris, pH 7.5 and 1 mM EDTA for a further 30 min, and baked at 80°C for 2 h.

The selected library was screened using α-32P dCTP-labeled fragments of Lawrist 16 and Lorist B as probes, and using a 350-bp PCR product containing the DYZ1 repeat, which had been amplified with STS map pair primers SY160.F and SY160.R (PubMed, accession no. G38343). As an extra precaution against the selection of repeat sequences, the library was also screened with α-32P dCTP-labeled and sonicated DNA from the OXEN cell line (49,XYYYY).

Posthybridization washes were performed at high stringency (0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS, 65°C). Filters were exposed to X-ray film (Kodak biomax MR) at −70°C for 4–24 h. Recombinant plasmids, which did not hybridize to vector or repeat sequence probes, were selected for further analysis.

PCR Amplification

DNA from selected recombinant plasmids was prepared using the ABI PRISM (Applied Biosystems) miniprep kits and cosmid DNA with the QIAGEN Plasmid Purification Maxi kit. PCR amplification of plasmid cDNA insert was performed using 50–200 ng of DNA, 1.5 units of Red Hot Taq polymerase (Advanced Biotech), 0.2 mM of dNTPs, and 25 pmoles of primers, in 15 mM MgCl2, 200 mM (NH4)2SO4, 750 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.8 and 0.1% Tween, in an Omnigene (Hybaid) thermal cycler. The cycling conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95°C for 5 min, 30–35 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 50–56°C, and 30 sec at 72°C, followed by 1 cycle at 72°C for 5 min.

cDNA inserts were amplified using the flanking vector primers pAMP10.F 5′ TAAGCTTGGATCCTCTAGAGCG 3′ and pAMP10.R 5′GAATTCCCGGGTCGACTACTAC 3′ (annealing temperature, 51°C). Primers common to all TTY2-like sequence were TTY2.F 5′TCACCACAGATAGCCACTGAGAC 3′ and TTY2.R 5′ATCAGGTCCATGGGATTGGAATG 3′. These were used to amplify TTY2-like sequences from a panel of cosmids (annealing temperature 50°C). Primers specific for the cDNA TTY2L12A and TTY2L2A were TTY2L12A.2F 5′CAGACTGTGAGTTGGTTCTG 3′ and TTY2L12A.R 5′TAT GTGAGAGAGACCCTGTG 3′ (annealing temperature, 54°C) and TTY2L2A.F 5′CCTATCTGAGCAGGTACTTTAC 3′ and TTY2L2A.R 5′GTGTCATCTGTCTTTCTCAGTG 3′ (annealing temperature 56°C), respectively.

DNA Sequence Analysis

Before sequence analysis, PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Sequence analysis was performed using a Thermo Sequenase radiolabeled terminator cycle sequencing kit (Amersham) and [α-33P] ddNTP terminators. Products were resolved on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (6% 19:1 acrylamide/bisacrylamide, 7 M urea, 1.7% (v/v) TEMED and 25% (w/v) ammonium persulphate), which was dried and exposed to X-ray film for 12–48 h at room temperature.

Automated fluorescent sequencing was also performed using dRhodamine fluorescent dye terminators (Advanced Biosystems) and an ABI 377XL automated DNA sequencer (Advanced Biosystems). Data was collected using 373XL collection software and analyzed using Sequencing Analysis version 3.0 and Sequence Navigator version 1.0.1 software.

RNA Preparation and RT-PCR

Before the preparation of RNA, sex determination of human tissues was performed from DNA using amelogenin primers AMLXY-forward and AMLXY-reverse (annealing temperature, 56°C) (Pertl et al. 1996).

RNA was extracted from male fetal and adult human tissues with RNAzol B (Biogenesis), following a procedure based on that described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (1987). The integrity of the RNA was checked by electrophoresis in 1% MOPS–formaldehyde agarose, in which RNA was visualized by adding ethidium bromide (100 ngmL−1) to the samples.

First-strand cDNA was prepared from RNA using MMuLV reverse transcriptase (Advanced Biotech) and ∼5 μg of RNA. The reaction mix contained 7 μL of 5× reverse transcriptase buffer (250 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.3, 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM DTT), 1 μL of 1000 pmoles random hexamer primers (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 2 μL of 20 mM dNTPs, 1 μL of ribonuclease inhibitor (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 3.5 μL of 0.1 M DTT, and DEPC-treated H2O in a total volume of 33 μL. Before addition of 2 μL (40 units) of reverse transcriptase, the RNA was denatured at 65°C for 10 min. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 90 min. Reactions without reverse transcriptase were also performed as a control to check for the presence of genomic DNA contamination.

cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR, using 2.5 μL of single-stranded cDNA, 25 pmoles of both forward and reverse primers, 5 mM of dNTPs, 1.5 units of Taq polymerase (Advanced Biotech) in 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1.25 mL of 200 mM (NH4)2SO4, 750 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.8, 0.1% Tween, in a final volume of 50 μL. After an initial denaturation step, 30–35 cycles were performed, using conditions established for each primer as described. The quality of the cDNA prepared from human tissues was checked using primers for the ubiquitously expressed gene phosphoglucomutase 1 (PGM1), with an annealing temperature of 56°C (Edwards et al. 1995).

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

FISH analysis was carried out as described previously (Gillett et al. 1996). Cultured lymphocytes were incubated with thymidine, to synchronize replication by blocking DNA synthesis. Cells were harvested, fixed, and transferred to cold slides. DNA (400 ng) was labeled with biotin–4-dATP or digoxigenin by nick translation (Bionick kit, GIBCO-BRL). The labeled probe was resuspended in hybridization mix, containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulphate, 2× SSPE, denatured and incubated with Cot1 DNA and herring sperm DNA for 24 h at 37°C, prior to incubation with the spreads. Signal detection was achieved using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated avidin for biotin and rhodamine antidigoxygenin. Preparations were mounted in vectashield antifade mounting medium, to which the fluorochrome diamidinophenylindole (DAPI) had been added for counterstaining and banding. Slides were examined under a Zeiss axioskop fluorescence microscope, and digital images were captured by a cooled CCD camera, using the Cyto Vision Ultra image collection and enhancement system (Applied Imaging).

Sequence Computational Analysis

Matches of cDNA sequences to sequences in database were looked for, using the BLAST program at the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nml.nih.gov/BLAST/), the HGMP BLAST search facilities (http://www.hgmp.mrc.ac.uk/), and the Tokyo GenomeNet database (http://www.blast.genome.ad.jp/). All sequence comparisons were performed by the programs BESTFIT and GAP, supplied as part of the GCG v.10 suite (Genetics Computer Group). CLUSTALX is also part of the MRC-HGMP bioinformatics facilities, and provided an integrating system for performing multiple sequence alignments.

The phylogenetic tree was constructed using a series of programs. Sequences of ∼250 bp were compared and aligned using the PILEUP program. The pairwise distance matrix was created using DISTANCES, and the phylogenetic tree was produced using the neighbor-joining method of GROWTREE and visualized using PAUPdisplay. Confidence of the tree was evaluated by 500 bootstrap replicates of the examined data, using the PAUP program.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Nabeel Affara for providing the Y chromosome YAC DNA, Dr. Richard Del Mastro for help in the construction of the cDNA selection library, Dr. Jonathan Wolfe and Dr. David Whitehouse for useful advice on databases and phylogenetic analyses, and Wendy Putt for technical assistance.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL yedwards@hgmp.mrc.ac.uk; FAX 44-207-387-3496.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.175901.

REFERENCES

- Archidiacono N, Storlazzi CT, Spalluto C, Ricco AS, Marzella R, Rocchi M. Evolution of chromosome Y in primates. Chromosoma. 1998;107:241–246. doi: 10.1007/s004120050303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnemann J, Epplen JT, Cooke HJ, Sauermann U, Engel W, Schmidtke J. A human Y-chromosomal DNA sequence expressed in testicular tissue. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8713–8724. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.21.8713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askew DS, Bartholomew C, Buchbert AM, Valentine MB, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Ihle JN. His-1 and His-2: Identification and chromosomal mapping of two commonly rearranged sites of viral integration in a myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 1991;6:2041–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BM. Human embryology and developmental biology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1994. The urogenital system; pp. 340–371. [Google Scholar]

- Chai NN, Salido EC, Yen PH. Multiple functional copies of the RBM gene family a spermatogenesis candidate on the human Y chromosome. Genomics. 1997;45:355–361. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J-F, Boyartchuk V, Zhu Y. Isolation and mapping of human chromosome 21 cDNA: Progress in constructing a chromosome 21 expression map. Genomics. 1994;23:75–84. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke H. Repeated sequence specific to human males. Nature. 1976;262:182–186. doi: 10.1038/262182a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ, Elliott DJ. RNA-binding proteins and human male infertility. Trends Genet. 1997;13:87–89. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Mastro RG, Lovett M. Isolation of coding sequences from Genomic regions using direct selection. Methods Mol Biol. 1997;68:183–199. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-482-8:183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy SR. Noncoding RNA genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:695–699. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards YH, Putt W, Fox M, Ives JH. A novel human phosphoglucomutase (PGM5) maps to the centromeric region of chromosome 9. Genomics. 1995;30:350–353. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann VA, Szymanski M, Hochberg A, Groot N, Barciszewski J. Non-coding, mRNA-like RNAs database Y2K. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:197–200. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatyol K, Illes K, Daimond DC, Janish C, Szalay AA. Mer22-related sequence elements form pericentric repetitive DNA families in primates. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;262:931–939. doi: 10.1007/pl00008661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlin A, Moro E, Onisto M, Toscano E, Bettella A, Foresta C. Absence of testicular DAZ gene expression in idiopathic severe testiculopathies. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2286–2292. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.9.2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan DJ. Transposable elements: How non-LTR retrotransposons do it. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R245–R248. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote S, Vollrath D, Hilton A, Page DC. The human Y chromosome: Overlapping DNA clones spanning the euchromatic region. Science. 1992;258:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.1359640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillett GT, Fox MF, Rowe PS, Casimir CM, Povey S. Mapping of human non-muscle type cofilin (CFL1) to chromosome 11q13 and muscle-typecofilin (CFL2) to chromosome 14. Ann Hum Genet. 1996;60:201–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1996.tb00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow P, Darling S, Wolfe J. The human Y chromosome. J Med Genet. 1985;5:329–344. doi: 10.1136/jmg.22.5.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M, Porter CA, Czelusniak J, Page SL, Schneider H, Shoshani J, Gunnell G, Groves CP. Towards a phylogenetic classification of primates based on DNA evidence complemented by fossil evidence. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1998;9:585–598. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1998.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimera J, Pucharcos C, Domenech A, Casas C, Solans A, Gallaardo T, Ashley J, Lovett M, Estivill X, Pritchard M. Cosmid contig and transcriptional map of three regions of human chromosome 21q22: Identification of 37 novel transcripts by direct selection. Genomics. 1997;45:59–67. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Crenshaw T, Moulton T, Newcomb E, Tycko B. Tumour-suppressor activity of H19 RNA. Nature. 1993;365:764–767. doi: 10.1038/365764a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MH, Khwaja OSA, Briggs H, Lambson B, Davey PM, Chalmers J, Zhou C-Y, Walker EM, Zhang Y, Todd C, et al. A set of ninety-seven overlapping yeast artificial chromosome clones spanning the human Y chromosome euchromatin. Genomics. 1994;24:266–275. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahn BT, Page DC. Functional coherence of the human Y chromosome. Science. 1997;278:675–680. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambson B, Affara NA, Mitchell M, Ferguson-Smith MA. Evolution of DNA sequence homologies between the sex chromosomes in primate species. Genomics. 1992;14:1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett M. Fishing for complements: Finding genes by direct selection. Trends Genet. 1994;10:353–357. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett M, Kere J, Hinton LM. Direct selection: A method for the isolation of cDNAs encoded by large genomic regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;58:9628–9632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Inglis JD, Sharkey A, Bickmore WA, Hill RE, Prosser EJ, Speed RM, Thomson EJ, Jobling M, Taylor K, et al. A Y chromosome gene family with RNA-binding protein homology: Candidates for the Azoospermia factor AZF controlling human spermatogenesis. Cell. 1993;75:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90616-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Sharkey A, Kirsch S, Vogt P, Keil R, Hargreave TB, McBeath S, Chandley AC. Towards the molecular localisation of the AZF locus: Mapping of microdeletions in azoospermic men within 14 subintervals of interval 6 of the human Y chromosome. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:29–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manz E, Schnieders F, Muller Brechlin A, Schmidtke J. TSPY related sequences represent a microheterogeneous gene family organized as constitutive elements in DYZ5 tandem repeat units on the human Y chromosome. Genomics. 1993;17:726–731. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martineau J, Nordqvist K, Tilmann C, Lovell-Badge R, Capel B. Male-specific cell migration into the developing gonad. Curr Biol. 1997;7:958–968. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller U, Lalande M, Donlon TA, Heartlein MW. Breakage of the human Y-chromosome short arm between two blocks of tandemly repeated DNA sequences. Genomics. 1989;5:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundlos S, Pelletier J, Darveau A, Bachmann M, Winterpacht A, Zabel B. Nuclear localization of the protein encoded by the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 in embryonic and adult tissues. Development. 1993;119:1329–1341. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson PL, Bobrow M, Vosa CG, Barlow PW. Quinacrine fluorescence in mammalian chromosomes. Nature. 1971;231:326–329. doi: 10.1038/231326a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertl B, Weitgasser U, Kopp S, Kroisel PM, Sherlock J, Adinolfi M. Rapid detection of trisomies 21 and 18 and sexing by quantitative fluorescent multiplex PCR. Hum Genet. 1996;98:55–59. doi: 10.1007/s004390050159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard-Jones K, Fleming S, Davidson D, Bickmore W, Porteous D, Gosden C, Bard J, Buckler A, Pelletier J, Housman D, et al. The candidate Wilms' tumour gene is involved in genitourinary development. Nature. 1990;346:194–197. doi: 10.1038/346194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor JL, Kent-First M, Muallem A, Van Bergen AH, Nolten WE, Meisner L, Roberts KP. Microdeletions in the Y chromosome of infertile men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:534–539. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratti A, Stuppia L, Gatta V, Fogh I, Calabrese G, Pizzuti A, Palka G. Characterisation of a new TSPY gene family member in Yq (TSPYq1) Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2000;88:159–162. doi: 10.1159/000015510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijo R, Lee T-Y, Salo P, Alagappan R, Brown LG, Rosenberg M, Rozen S, Jaffe T, Straus D, Hovatta O, et al. Diverse spermatogenic defects in humans caused by Y chromosome deletions encompassing a novel RNA-binding protein gene. Nat Genet. 1995;10:383–393. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena R, Brown LG, Hawkins T, Algappan RK, Skaletsky H, Reeve MP, Reijo R, Rozen S, Dinulos MB, Disteche CM, et al. The DAZ gene cluster on the human Y chromosome arose from an autosomal gene that was transposed, repeatedly amplified and pruned. Nat Genet. 1996;14:292–299. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schempp W, Binkele A, Arnemann J, Gläser B, Ma K, Taylor K, Toder R, Wolfe J, Zeitler S, Chandley AC. Comparative mapping of YRRM and TSPY sequences in man and hominoid ape. Chr Res. 1995;3:227–234. doi: 10.1007/BF00713047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnieders F, Dörk T, Arnemann J, Vogel T, Werner M, Schmidtke J. Testis-specific protein, Y encoded (TSPY) expression in testicular tissues. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1801–1807. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.11.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons AD, Goodart SA, Gallardo TD, Overhauser J, Lovett M. Five novel genes form the cri-du-chat critical region isolated by direct selection. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:295–302. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons AD, Overhauser J, Lovett M. Isolation of cDNAs from the Cri-du-chat critical region by direct screening of a chromosome 5 specific cDNA library. Genome Res. 1997;7:118–127. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair AH, Berta P, Palmer MS, Hawkins JR, Griffiths BL, Smith MJ, Foster JW, Frischauf A-M, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PN. A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature. 1990;346:240–244. doi: 10.1038/346240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit AF. Interspersed repeats and other mementos of transposable elements in mammalian genomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:657–663. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Ferguson MA, Affara NA, Maggenis RE. Ordering of Y-specific sequences by deletion mapping and analysis of X–Y interchange males and females. Development (Suppl.) 1987;101:41–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.Supplement.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland HF, Wadey R, McKie JM, Taylor C, Atif U, Johnstone KA, Halford S, Kim U-J, Goodship J, Baldini A, et al. Identification of a novel transcript disrupted by a balanced translocation associate with DiGeorge Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:23–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor K, Hornigold N, Conway D, Williams D, Ulinowski Z, Agochiya M, Fattorini P, de Jong P, Little PF, Wolfe J. Mapping the human Y chromosome by fingerprinting cosmid clones. Genome Res. 1996;6:235–248. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.4.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiepolo L, Zuffardi O. Localization of factors controlling spermatogenesis in the nonfluorescent portion of the human Y chromosome long arm. Hum Genet. 1976;34:119–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00278879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchman JW, Bouffard GG, Weintraub LA, Idol JR, Wang L, Robbins CM, Nussbaum JC, Lovett M, Green ED. 2006 expressed-sequence tags derived from human chromosome 7-enriched cDNA libraries. Genome Res. 1997;7:281–292. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnaud G, Page DC, Simmler MC, Brown L, Rouyer F, Noel B, Botstein D, de la Chapelle A, Weissenbach J. A deletion map of the human Y chromosome based on DNA hybridization. Am J Hum Genet. 1986;38:109–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel T, Schmidtke J. Structure and function of TSPY, the Y chromosome gene coding for the “testis-specific protein.”. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;80:209–213. doi: 10.1159/000014982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt PH, Edelmann A, Kirsch S, Henegariu O, Hirschmann P, Kiesewetter F, Kohn FM, Schill WB, Farah S, Ramos C, et al. Human Y chromosome azoospermia factors (AZF) mapped to different subregions in Yq11. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:933–943. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt PH, Rappold GA, Lau CYF. Third international workshop on human Y chromosome mapping. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;79:1–20. doi: 10.1159/000134680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath D, Foote S, Hilton A, Brown LG, Beer-Romero P, Bogan JS, Page DC. The human Y chromosome: A 43-interval map based on naturally occurring deletions. Science. 1992;258:52–59. doi: 10.1126/science.1439769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]