Abstract

Transgenic mice are increasingly used as animal models for studies of gene function and regulation of mammalian genes. Although there has been continuous and remarkable progress in the development of transgenic technology over several decades, many aspects of the resulting transgenic model’s phenotype cannot be completely predicted. For example, it is well known that as a consequence of the random insertion of the injected DNA construct, several founder mice of the new line need to be analyzed for possible differences in phenotype secondary to different insertion sites. The Knock out technique for transgenic production disrupts a specific gene by insertion or homologous recombination creating a null expression or replacement of the gene with a marker to localize it expression. This modification could result in pleiotropic phenotype if the gene is also expressed in tissues other than the target organs. Although the future breeding performance of the newly created model is critical to many studies, it is rarely anticipated that the new integrations could modify the reproductive profile of the new transgenic line. To date, few studies have demonstrated the difference between the parent strain’s reproductive performance and the newly developed transgenic model. This study was designed to determine whether a genetic modification, knock out (KO) or transgenics, not anticipated to affect reproductive performance could affect the resulting reproductive profile of the newly developed transgenic mouse. More specifically, this study is designed to study the impact of the genetic modification on the ability of gametes to be fertilized in vitro. We analyzed the reproductive performance of mice with different background strains: FVB/N, C57BL/6 (129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 and outbred CD1® and compared them to mice of the same strain carrying a transgene or KO which was not anticipated to affect fertility. In vitro Fertilization was used to analyze the fertility of the mice. Oocytes from superovulated females were inseminated with sperm of same background. Fertility rate was considered as the percentage of two cell embryos scored 24 h after insemination. The data collected from this study shows that the fertilization rate is affected (reduced to half fold) in some of the transgenic mice compared to the respective Wild Type (WT) mice. For the WT the average fertility rate ranged from 80% (C57BL/6), 90% (FVB/N), 45% (129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 and 43% (CD1). For transgenic mice it was 52% (C57BL/6), 65% (FVB/N), 22% (129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 and 25% (CD1).

Keywords: Transgenic mice, IVF, Superovulation, Cryopreservation

Introduction

The technique of pronuclear microinjection, which allows the introduction of engineered DNA into the pronucleus of a fertilized egg to modify the genetics of a mouse line, was first developed by (Gordon et al. 1980). This powerful tool became a firmly established technique, when optimized protocols for the procedure were published over two decades ago (Brinster et al. 1985; Hogan 1986). Since then, transgenic mice have been the most popular models used for studies of gene function and its regulation as demonstrated by thousands of publications utilizing transgenic animal models for biomedical investigations. The knockout technology where one or more genes have been turned off through homologous recombination or insertion has permitted scientists to determine the role of specific genes in development, physiology, and pathology.

For most studies, the development of a transgenic or knockout animal was only the first step in the process of developing and characterizing a unique line. Same as the natural mating where mice have different indices of fertility (Sztein et al. 2000; Styrna and Krzanowska 1995; Niwa et al. 1980; Kaleta 1977; Parkening and Chang 1976) the fertility rate of the genetically modified mice is also influenced by the genetic background. Subsequently, genetic differences were also observed in the superovulation rate (Spearow and Barkley 1999), the post thaw survival of cryopreserved spermatozoa (Sztein et al. 2000, 2001; Thornton et al. 1999) and the rate of embryo development (Scott and Whittingham 1996) in mice of different background strains. Since the genetic background plays a major role on the in vivo reproductive performance of each mouse strain the success of other in vitro Assisted Reproduction Techniques (i.e. in vitro fertilization (IVF), cryopreservation, etc.) may also be linked to the genetic background of the mouse under consideration. In this study we used IVF as a tool to produce fertilized embryos and analyzed the reproductive profile of several transgenic mouse lines with different strain backgrounds and compared the fertility rate of each transgenic line to it’s wild-type background strain.

Materials and methods

Animals

Transgenic and KO male and female mice from different background strains such as inbred: FVB/NCrl, C57BL/6NCrl, outbred Crl:CD1(ICR; Charles River) and [129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 (Lu et al. 1998)] strains were maintained in a breeding program (brother × sister mating) under a centralized breeding program in facilities accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International (AAALAC). The genetically modified animals used in the study are described in Table 1. None of the strains selected has a genetic modification expected to alter the breeding performance. The animal housing included a controlled light and dark cycle (12 h:12 h), ad libitum food, Purina Labdiet 502, 9%—Fat Breeding chow and ultra filtered water, ventilated caging systems and standardized environmental enrichment. Male mice were housed individually for at least 5 days prior to the collection of spermatozoa. This study was carried out with mouse strains sent for cryopreservation to our unit. Although CD1 and (129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 have only one transgenic strain each, they were included in the study with the rational of having different transgenics backgrounds.

Table 1.

List of transgenic mice used in this study

| Name | Promoter | Gene | Target | Zygocity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRBP KO1 | IRBP coding region | Inter-photo-receptor retinoid binding protein gene | Homo | Cortes et al. (2008) | |

| IL18 KO2 | IL18 | IL18 | Homo | Hochholzer et al. (2000) | |

| Ig-NRG1 KO3 | NRG1 | Ig-like domain | Hetero | Kramer et al. (1996) | |

| ErbB44 | Actin | ErbB4 | Heart/mammary gland | Homo | Tidcombe et al. (2003) |

| MyoCre5 | Myogenin | Cre recombinase | Muscle fiber | Homo | a |

| PRL16 | Alpha-A-crystalline | Hen egg lysozyme | Eye | Homo | Lai et al. (1998) |

| PRL27 | |||||

| MCP-1ccl2 KO8 | MCP-1 | White cells | Hetero | Lu et al. (1998) | |

| RPE65-GFP-RAS9 | RPE | GFP | RPE membrane | Hetero | Redmond et al. (1998) |

List of transgenic lines used in the study describing the strains, type of transgene and target organ. The homozygosity: homo homozygous, hetero heterozygous

The superscript numerals 1, 2, 3, 4 indicate strain C57BL/6; 5, 6, 7 indicate FVB/N; 8 indicates (129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 and 9 indicates CD1

The superscript letter a means no publication

In vitro fertilization

In vitro fertilization was performed using a modified version of the method described by Sztein et al. 2000. In vitro fertilization culture medium, Mouse Vitro Fert (Cook V-MVFE-50, Australia), was used for sperm incubation, IVF and zygotes culture.

Sperm was collected from the caudae epididymides of 3–5 month old male mouse as described in Sztein et al. 2000. After euthanasia with CO2 both caudae epididymides and vas deferentia were removed aseptically and placed in 300 µl of IVF media (Cook V-MVFE-50, Australia) covered with embryo tested mineral oil (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in a 35-mm dish (Falcon 1008, Becton–Dickinson, NJ). The tissue was incised 4–5 times with the edge of a 30G injection needle to allow the sperm to “swim out” and disperse for 20–30 min at 37°C under 5% CO2 in the humidified incubator. Sperm motility and concentration was confirmed by visual observation.

Five to ten 21–35 day old female mice were superovulated by intraperitoneal injection (IP) of 5 international units (IU) of Gonadotropin from Pregnant Mare Serum (PMSG; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Forty-six to fifty hours post PMSG were injected with 5 IU of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) intraperitoneally. Thirteen to fifteen hours following HCG administration, the female mice were euthanized with CO2; their oviducts were aseptically removed and dissected free from surrounding tissues and placed in a culture dish containing 2 ml of M2 medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) warmed at 37°C. The cumulus oocytes complexes were removed from the ampullae using micro dissecting forceps and subsequently used for the IVF procedure.

Ten micro liters of the sperm suspension was added using a wide-bore pipette tip to a 250 µl IVF media drop covered with embryo tested mineral oil (Sigma). The isolated oocytes complexes were then transferred to the drop of media containing the sperm and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air for 5 h. After that time the eggs were washed to eliminate excess sperm and cultured overnight in a 250-µl drop of IVF medium under the same conditions. The following day the number of two-cell embryos were counted and prepared for either transfer to recipient females or for cryopreservation. The oocytes from the superovulated females were pooled for each IVF and the experiment was done 3 or more times for each line.

Statistical analysis

Fertility was considered as the percentage of two cell stage embryos scored 24 h after insemination. For the statistical analysis the percentages were transformed into arcsine values and then evaluated by one-way ANOVA and by unpaired t test (two tailed). For the C57BL6 and FVB/N background mice the Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test was used to compare all transgenic mice against the WT mice. Differences were considered to be significant when a P value of <0.05 was obtained. Error bars on figures represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) of the in vitro fertilization rate. The data was analyzed using the Graph Pad Prism version 5.0 computer program (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

The results of the in vitro fertilization procedure are summarized in the tables and figures displaying the average fertilization rate (percentage of zygotes which progressed to the two-cell stage) obtained from a minimum of three IVF tests. Fertility was scored at the two-cell stage embryos after overnight culture in IVF medium (MVFE-50) at 37°C under 5% CO2 in humidified environment. The fertility rate was calculated by dividing the number of 2 cells by total number of oocytes exposed. The results show that the fertility rate varied between the WT and transgenic line of same background strain.

The average fertilization for WT C57BL/6 mice as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1 was 80 ± 5% and the average fertilization for all four C57BL/6 transgenic mice was 48 ± 7%. Although the fertility rate between the wt and the transgenic mice turned out to be not significative different after the arcsine transformation, in two groups the rates obtained have 50% difference.

Table 2.

Summary of in vitro fertilization (IVF) results of the WT and the transgenic mice of C57BL/6 strain

| Strain | Total # of females |

Total # of oocytes |

Average # of oocytes per female |

Total # of 2 cells |

IVF % (mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 15 | 474 | 32 | 378 | 80 ± 5a |

| KO1 | 27 | 344 | 13 | 88 | 40 ± 11a |

| KO2 | 15 | 353 | 24 | 229 | 64 ± 10a |

| KO3 | 22 | 710 | 32 | 235 | 33 ± 1a |

| Tg1 | 24 | 594 | 25 | 324 | 69 ± 23a |

The data shown in the table represent cumulative results of all IVF experiments. Average fertilization for each IVF was calculated by dividing the number of two cell embryos by the number of total oocytes. The IVF was performed three times for the WT and on an average of 4 times for the transgenic mice. The percentage rate transformed by arcsine was used for the Dunnett’s test to compare all the transgenic mice against the WT mice.

Superscript letters a represent no significant differences (P < 0.05) among the groups

Fig. 1.

In vitro fertilization rate of WT and transgenic mice of C57BL/6 strain. Fertility was scored at two cell stage after overnight culture in IVF medium. Each bar represents the mean IVF rate from a total of three or more IVF for each line

Table 3 and Fig. 2 show the average fertilization for the WT FVB/N mice was 90 ± 5% and the average fertilization for all the transgenic mice was 65 ± 8%. One of the FVB/N transgenic lines had a significantly reduced fertility rate (P < 0.05) 50 ± 8% compared to the WT mice 90 ± 5%.

Table 3.

Summary of in vitro fertilization (IVF) results of the WT and the transgenic mice of FVB/N strain

| Strain | Total # of females |

Total # of oocytes |

Average # of oocytes per female |

Total # of 2 cells |

IVF % (mean ± S.E.M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 15 | 181 | 12 | 164 | 90 ± 5a |

| Tg1 | 15 | 305 | 20 | 249 | 80 ± 8a |

| Tg2 | 54 | 890 | 16 | 444 | 50 ± 8b |

| Tg4 | 42 | 782 | 19 | 526 | 65 ± 12a |

Within a column, superscript letters a, b represent significant differences (P < 0.05)

Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test using the percentages transformed by arcsine was applied to compare all the transgenic mice against WT mice. The IVF was performed three times for WT, on an average of four times for transgenic mice

Fig. 2.

In vitro fertilization rate of WT and transgenic mice of FVB/N strain. Fertility was considered as the percentage of two cell stage embryos after overnight culture in IVF medium. Each bar represents the mean IVF rate from a total of three or more IVF for each line

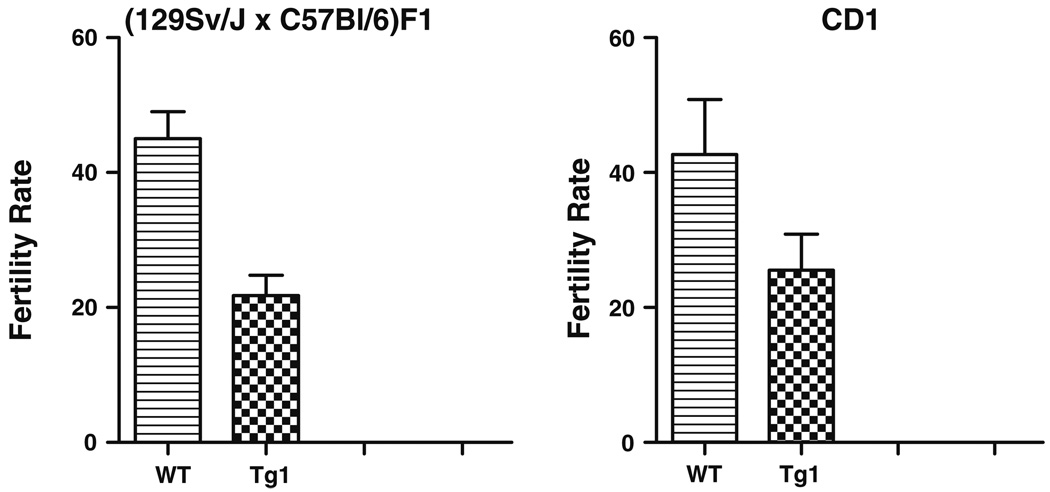

For the WT (129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 the fertilization rate was 45 ± 4% and the transgenic mice was significantly lower (P < 0.05) 22 ± 3%. For the CD1 WT it was 43 ± 8% and the transgenic mice was 25 ± 5%. This result is not significantly different (P < 0.05). Both results are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 3.

Table 4.

Summary of in vitro fertilization (IVF) results of the WT and the transgenic mice of (129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 (in italic) and CD1 (in bold) strain

| Strain | Total # of females |

Total # of oocytes |

Average # of oocytes per female |

Total # of 2 cells |

IVF % (mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 30 | 504 | 17 | 223 | 45 ± 4a |

| KO | 95 | 1,576 | 17 | 309 | 22 ± 3b |

| WT | 15 | 313 | 21 | 152 | 43 ± 8a |

| Tg | 59 | 1,265 | 21 | 264 | 25 ± 5a |

For each strain superscript letters a, b represent significant differences (P < 0.05).

Unpaired t test (two tailed) was used to compare the transgenic mice with the WT mice. IVF was performed three times for WT and on an average of 4 times for genetically modified mice

Fig. 3.

In vitro fertilization rate of WT and transgenic mice of (129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 and CD1 strain. Fertility was considered as the percentage of two cell stage embryos after overnight culture in IVF medium. Each bar represents the mean IVF rate from a total of three or more IVF for each line

Discussion

Archiving mouse strains by embryo cryopreservation has great potential because it is simple, rapid, and inexpensive. The use of IVF for producing embryos for rederivation and/or embryo banking, even under some difficult circumstances can speed up and in some cases improve the process of cryopreservation. However, the success of the cryopreservation is influenced by the genetic background and the reproductive performance of the mice used (Choi et al. 2000; Fraser 1977; Parkening and Chang 1976). A Number of differences exists between the mouse strains commonly used in the research field and in transgenic technology (e.g., B6; 129 × 1/SvJ, FVB/N and BALB/c). Reproductive traits such as litter size, sperm production and hormone induced ovulation rate differ between mouse strains (Bouxsein et al. 2005; Spearow and Barkley 1999; Silver 1995). Also the in vitro fertilization in mice varies depending on genotype and the conditions used for capacitation and fertilization (Sztein et al. 2000; Choi et al. 2000; Fraser 1977; Parkening and Chang 1976; Fraser and Drury 1976; Iwamatsu and Chang 1971). Further, inbred mouse strains have defined reproductive parameters which are so distinctive that they are considered to be a characteristic of the strain (Byers et al. 2006; Silver 1995). Inbred strains also differ in their capacity for embryo development in culture (Scott and Whittingham 1996; Roudebush and Duralia 1996; Dandekar and Glass 1987) and in survival after embryo cryopreservation (Dinnyes et al. 1995; Pomp and Eisen 1990; Schmidt et al. 1985).

During the transgenic mice production, the genetic background characteristic of the newly established strain can be serendipitously modified by the insertion of DNA construct or by the process of knocking out a gene which can impact the mice response to superovulation and its fertility. The integration of the exogenous DNA occurs at apparently random locations within the mouse genome. Occasionally the integration of the transgene can fortuitously interrupts an intrinsic mouse gene responsible for some interesting aspect of mouse development and causes a special class of mutations referred as “insertional mutations” (Palmiter and Brinster 1986). Insertional mutations may lead to a variety of phenotypes such as embryonic lethalities (Covarrubias et al. 1987; Soriano et al. 1987; Mark et al. 1985; Wagner et al. 1983), morphological, neurological disorders (Zeller et al. 1989; Krulewski et al. 1989; McNeish et al. 1988; Kothary et al. 1988; Overbeek et al. 1986) and abnormal sperm functions (Palmiter et al. 1984). Magram and Bishop (1991) showed that male hemizygous transgenic mice carrying HCK protooncogene were sterile due to a defect in spermatogenesis. They found that the sterile males mated normally but failed to impregnate the females due to the presence of a variety of abnormally shaped nuclei during spermatogenesis.

This study was conducted to determine whether there is a difference in the reproductive performance between transgenic mice and wild-type (WT) mice of the same background strain. Reproductive performance was analyzed by the number of oocytes fertilized by IVF. Fertility was scored at the two cell stage-stage embryos. From the results we observed that the reproductive performance of the WT mice and the transgenic mice of same background strain was different. This statistical difference of the normalized distribution is not significant for the C57BL/6 and CD1 strains, however, it was for FVB/N and (129Sv/J × C57Bl/6)F1 lines (P < 0.05) used in this study. The FVB/N mice have a better IVF outcome compared to some other inbred strains. In this study one of the FVB/N transgenic mice lines had a low fertility rate of 50% compared to the WT fertility rate of 90%. This study clearly demonstrates a direct effect of the man made genetic modification on the gametes of the resulting transgenic line. The variation in fertility between the WT mice and the transgenic mice of same background strain could be perhaps, due to the consequence caused by the transgene insertion resulting in disruption of a gene (or genes) important, or the insertion causing the knock out of a gene which could be linked to gametogenesis resulting in abnormal sperm production, oocyte genesis or others factors regulating fertility. It has been described that knockout mice that have a silenced functional gene expressing in tissues which are not directly involved in reproduction may show a pleiotropic phenotype with reduced fertility (Baker et al. 1995). Toshimori et al. (2004) described various gene KO models where the decrease in sperm production could be induced as a secondary effect of gene knock out. Alternatively, the result could be a direct effect on gametogenesis. It should be noted that only two of the transgenic mice used in the study carries a marker or neutral gene and all the others have active expressing genes, although none of the transgenic mice used in this study had any gene modification related to neither reproduction nor an expected phenotype that could affect fertility. Therefore, the fertility variation observed in this study could be a possible effect of the modification caused by the integration of a transgene or KO of a gene.

Although the statistical analysis of some of the lines showed no significant difference between wt and transgenic mice, in the practice, harvesting 50% less number of embryos implicates the use of more females, longer time to complete the cryopreservation of projected number, more time for housing the colony and therefore, total more expenses. Then, the variations in the fertility rate between the WT mice and the transgenic mice of same background strain described in this study should be taken under consideration while planning any assisted reproduction procedure (i.e. embryo rederivation, cryopreservation, colony expansion, etc.), especially in relation to the time it takes to complete the embryo banking or rederivation by means of IVF. For transgenic lines which are difficult to breed or collect embryos for archiving, other options may of benefit such as using WT females with the Tg males for IVF or for breeding to preserve the valuable genotype.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christine Force for technical assistance. This study was funded by National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Kuzhalini Vasudevan, Email: vasudevk@mail.nih.gov.

Jorge Sztein, Email: szteinj@niaid.nih.gov.

References

- Baker SM, Bronner CE, Zhang L, Plug AW, Robatzek M, Warren G, Elliott EA, Yu J, Ashley T, Arnheim N, Flavell RA, Liskay RM. Male mice defective in the DNA mismatch repair gene PMS2 exhibit abnormal chromosome synapses in meiosis. Cell. 1995;82(2):309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouxsein ML, Myers KS, Shultz KL, Donahue LR, Rosen CJ, Beamer WG. Ovariectomy induced bone loss varies among inbred strains of mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(7):1085–1092. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster RL, Chen HY, Trumbauer ME, Yagle MK, Palmiter RD. Factors affecting the efficiency of introducing foreign DNA into mice by microinjecting eggs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(13):4438–4442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers SL, Payson SJ, Taft RA. Performance of ten inbred mouse strains following assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) Theriogenology. 2006;65(9):1716–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YH, Seng S, Toyoda Y. Comparison of capacitation and fertilizing ability of BALB/c and ICR mice epididymal spermatozoa: analysis by in vitro fertilization with cumulus intact and zona-free mouse eggs. J Mamm Ova Res. 2000;17(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes LM, Mattapallil MJ, Silver PB, Donoso LA, Liou GI, Zhu W, Chan CC, Caspi RR. Repertoire analysis and new pathogenic epitopes of IRBP in C57BL/6 (H-2b) and B10.RIII (H-2r) mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(5):1946–1956. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias L, Nishida Y, Terao M, D’Eustachio P, Mintz B. Cellular DNA rearrangements and early developmental arrest caused by DNA insertion in transgenic mouse embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7(6):2243–2247. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandekar PV, Glass RH. Development of mouse embryos in vitro is affected by strain and culture medium. Gamete Res. 1987;17(4):279–285. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1120170402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnyes A, Wallace GA, Rall WF. Effect of genotype on the efficiency of mouse embryo cryopreservation by vitrification or slow freezing methods. Mol Reprod Dev. 1995;40(4):429–435. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080400406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser LR. Differing requirements for capacitation in vitro of mouse spermatozoa from two strains. J Reprod Fertil. 1977;49(1):83–87. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0490083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser LR, Drury LM. Mouse sperm genotype and the rate of egg penetration in vitro. J Exp Zool. 1976;197(1):13–19. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401970103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JW, Scangos GA, Plotkin DJ, Barbosa JA, Ruddle FH. Genetic transformation of mouse embryos by microinjection of purified DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77(12):7380–7384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochholzer P, Lipford GB, Wagner H, Pfeffer K, Heeg K. Role of interleukin-18(IL-18) during lethal shock: decreased lipopolysaccharide sensitivity but normal superantigen reaction in IL-18 deficient mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68(6):3502–3508. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3502-3508.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual. 2nd edn. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamatsu T, Chang MC. Factors involved in the fertilization of mouse eggs in vitro. J Reprod Fert. 1971;26:197–208. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0260197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaleta E. Influence of genetic factors on the fertilization of mouse ova in vitro. J Reprod Fertil. 1977;51(2):375–381. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0510375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothary R, Clapoff S, Brown A, Campbell R, Peterson A, Rossant J. A transgene containing lacZ inserted into the dystonia locus is expressed in neural tube. Nature. 1988;335(6189):435–437. doi: 10.1038/335435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer R, Bucay N, Kane DJ, Martin LE, Tarpley JE, Theill LE. Neuregulins with an Ig-like domain are essential for mouse myocardial and neuronal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(10):4833–4838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krulewski TF, Neumann PE, Gordon JW. Insertional mutation in a transgenic mouse allelic with Purkinje cell degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(10):3709–3712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai JC, Fukushima A, Wawrousek EF, Lobanoff MC, Charukamnoetkanok P, Smith-Gill SJ, Vistica BP, Lee RS, Egwuagu CE, Whitcup SM, Gery I. Immunotolerance against a foreign antigen transgenically expressed in the lens. IOVS. 1998;39(11):2049–2057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Rutledge BJ, Gu L, Fiorillo J, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL, North R, Gerard C, Rollins BJ. Abnormalities in monocyte recruitment and cyotokine expression in monocyte chemoattractant protein 1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187(4):601–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magram J, Bishop JM. Dominant male sterility in mice caused by insertion of a transgene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(22):10327–10331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark WH, Signorelli K, Lacy E. An insertional mutation in a transgenic mouse line results in developmental arrest at day 5 of gestation. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1985;50:453–463. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1985.050.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeish JD, Scott WJ, Jr, Potter SS. Legless, a novel mutation found in PHT1-1 transgenic mice. Science. 1988;241(4867):837–839. doi: 10.1126/science.3406741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa K, Araki M, Iritani I. Fertilization in vitro of eggs and first cleavage of embryos in different strains of mice. Biol Reprod. 1980;22(5):1155–1159. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/22.5.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek PA, Lai SP, Van Quill KR, Westphal H. Tissue-specific expression in transgenic mice of a fused gene containing RSV terminal sequesnces. Science. 1986;231(4745):1574–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.3006249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Germ-line transformation of mice. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:465–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.002341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmiter RD, Wilkie TM, Chen HY, Brinster RL. Transmission distortion and mosaicism in an unusual transgenic mouse pedigree. Cell. 1984;36(4):869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkening TA, Chang MC. Strain differences in the in vitro fertilizing capacity of mouse spermatozoa as tested in various media. Biol Reprod. 1976;15(5):647–653. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod15.5.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomp D, Eisen EJ. Genetic control of survival of frozen mouse embryos. Biol Reprod. 1990;42(5–6):775–786. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod42.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond TM, Yu S, Lee E, Bok D, Hamasaki D, Chen N, Goletz P, Ma JX, Crouch RK, Pfeifer K. Rpe65 is necessary for production of 11-cis-vitamin A in the retinal visual cycle. Nat Genet. 1998;20(4):344–351. doi: 10.1038/3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudebush WE, Duralia DR. Superovulation, fertilization, and in vitro embryo development in BALB/cByJ, BALB/cJ, B6D2F1/J, and CFW mouse strains. Lab Anim Sci. 1996;46(2):239–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt PM, Hansen CT, Wildt DE. Viability of frozen-thawed mouse embryos is affected by genotype. Biol Reprod. 1985;32(3):507–514. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod32.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L, Whittingham DG. Influence of genetic background and media components on the development of mouse embryos in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;43(3):336–346. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199603)43:3<336::AID-MRD8>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver LM. Mouse genetics: concept and applications. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P, Gridley T, Jaenisch R. Retroviruses and insertional mutagenesis in mice: proviral integration at the Mov 34 locus leads to early embryonic death. Genes Dev. 1987;1(4):366–375. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spearow JL, Barkley M. Genetic control of hormone-induced ovulation rate in mice. Biol Reprod. 1999;61(4):851–856. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.4.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styrna J, Krzanowska H. Sperm select penetration test reveals differences in sperm quality in strains with different Y chromosome genotype in mice. Arch Androl. 1995;35(2):111–118. doi: 10.3109/01485019508987861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztein JM, Farley JS, Mobraaten LE. In vitro fertilization with cryopreserved inbred mouse sperm. Biol Reprod. 2000;63(6):1774–1780. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztein JM, Noble MK, Farley JS, Mobraaten LE. Comparison of permeating and nonpermeating cryoprotectants for mouse sperm cryopreservation. Cryobiology. 2001;42(1):28–39. doi: 10.1006/cryo.2001.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton CE, Brown SD, Glenister P. Large numbers of mice established by in vitro fertilization with cryopreserved spermatozoa: implications and applications for genetic resource banks, mutagenesis screens, and mouse backcrosses. Mamm Genome. 1999;10(10):987–992. doi: 10.1007/s003359901145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidcombe H, Jackson-Fisher A, Mathers K, Stern DF, Gassmann M, Golding JP. Neural and mammary gland defects in ErbB4 knockout mice genetically rescued from embryonic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(14):8281–8286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1436402100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshimori K, Ito C, Maekawa M, Toyama Y, Suzuki-Toyota F, Saxena DK. Impairment of spermatogenesis leading to infertility. Anat Sci Int. 2004;79(3):101–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-073x.2004.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EF, Covarrubias L, Stewart TA, Mintz B. Prenatal lethalities in mice homozygous for human growth hormone sequences integrated in the germ line. Cell. 1983;35(3 pt 2):647–655. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller R, Jackson-Grusby L, Leder P. The limb deformity gene is required for apical ectodermal ridge differentiation and anteroposterior limb pattern formation. Genes Dev. 1989;3(10):1481–1492. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]