Abstract

There is substantial interest in implementing technologies that allow comparisons of whole genomes of individuals and of tissues and cell populations. Restriction landmark genome scanning (RLGS) is a highly resolving gel-based technique in which several thousand fragments in genomic digests are visualized simultaneously and quantitatively analyzed. The widespread use of RLGS has been hampered by difficulty in deriving sequence information for displayed fragments and a lack of whole-genome sequence-based framework for interpreting RLGS patterns. We have developed informatics tools for comparisons of sample derived RLGS patterns with patterns predicted from the human genome sequence and displayed as Virtual Genome Scans (VGS). The tools developed allow sequence prediction of fragments in RLGS patterns obtained with different restriction enzyme combinations. The utility of VGS is demonstrated by the identification of restriction fragment length polymorphisms, and of amplifications, deletions, and methylation changes in tumor-derived CpG islands and the characterization of an amplified region in a breast tumor that spanned <230 kb on 17q23.

Several electrophoretic approaches have been investigated for the separation of genomic DNA in two dimensions to allow comparisons of genomes of different individuals or tissues. Fischer and Lerman (1979) and others relied on two independent modes, size in the first dimension and mobility in a denaturing gradient in a second dimension, to separate and probe whole-genome DNA restriction fragments (Fischer and Lerman 1979; Uitterlinden et al. 1989; Qiu et al. 1997). A probe-free method was developed, referred to as Restriction Landmark Genome Scanning (RLGS), in which genomic DNA is radioactively labeled at cleavage sites specific for a rare cleaving restriction enzyme, followed by first-dimension electrophoresis. By subjecting separated DNA fragments to in situ digestion with a frequent cutter prior to a second-dimension electrophoresis, several thousand fragments from throughout the genome can be resolved and visualized (Hatada et al. 1991). The reliance on the rare cleavage enzyme NotI to digest genomic DNA prior to labeling generates landmarks that allow visualization of DNA fragments that occur preferentially in CpG islands (Lindsay and Bird 1987). Because of the localization of CpG islands in proximity to transcribed sequences (Larsen et al. 1992), there is a strong likelihood that NotI fragments detected in RLGS scans occur in the vicinity of coding sequences.

There are numerous applications of RLGS stemming from its quantitative reproducibility. We have shown previously the feasibility of utilizing RLGS to distinguish spot intensities representing fragments that occur in one copy in the genome from spot intensities representing fragments that occur in two copies (Asakawa et al. 1994; Kuick et al. 1995). Thus, RLGS could be useful for studies of restriction fragment length polymorphisms, for identifying genomic insertions, deletions, or amplifications, and for identifying somatic methylation changes (Kim et al. 1996; Thoraval et al. 1996a,b; Corn et al. 1999; Wimmer et al. 1999; Eng et al. 2000).

There is a critical need to identify DNA fragments of interest displayed in RLGS scans. Some strategies that rely on extraction of DNA fragments from gels for their cloning (Hirotsune et al. 1993) or on their PCR amplification (Suzuki et al. 1994) have been utilized but have proven difficult in the case of fragments that occur in two copies or less in the genome. An arrayed genomic library approach has been utilized to overcome this problem, resulting in assignment of clones to unique fragments observed in the gel (Smiraglia et al. 1999). Limitations of this approach are attributable to limited library coverage. The near completion of sequencing of the human genome has prompted us to develop genome sequence-based tools to facilitate the identification of fragments of interest.

RESULTS

Virtual Genome Scans Derived from the Sequence of the Human Genome

The most frequently utilized initial enzyme for cutting and tagging genomic fragments in RLGS is NotI, with EcoRV being utilized to further reduce the size of NotI fragments, prior to first-dimension electrophoresis. For the second-dimension separation, fragments are digested in situ, using any one of a number of frequent cutting enzymes that can efficiently digest DNA in gels to provide an independent second-dimension separation mode. We have developed informatics tools that yield virtual genome scans using NotI and EcoRV as first dimension enzymes and HinfI or DpnII as second-dimension enzymes. We have chosen these four enzymes because they are utilized most frequently in RLGS studies. However this approach could be applied to any set of enzymes and any sequenced genome. The current version of Virtual Genome Scans (VGS1.01) is based on approximately a quarter (24.7%) of the human genome sequence that is available through GenBank as finished sequence, and on the remainder that is available as draft sequence (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/seq/). The finished sequence set consists of 648,560 kb and the draft sequence set consists of 2,579,072 kb.

For each set of sequence data, we computed the size of the NotI–EcoRV fragments or the size of a NotI–NotI fragment if no EcoRV site is present between two NotI sites. We also computed the size of second-dimension fragments based on the HinfI (or DpnII) site that is nearest to NotI. We then merged the final and draft sequence sets and removed redundancy resulting from overlapping clones in the draft sequence set. Thus, we obtained 4840 fragments for HinfI and 5210 fragments for DpnII that had first- and second-dimension size ranges (0.8–16 kb, and 135–2700 bp, respectively) that corresponded to the separation ranges of our standard RLGS patterns. These numbers represented ∼50% of the total number of fragments detected in the genome.

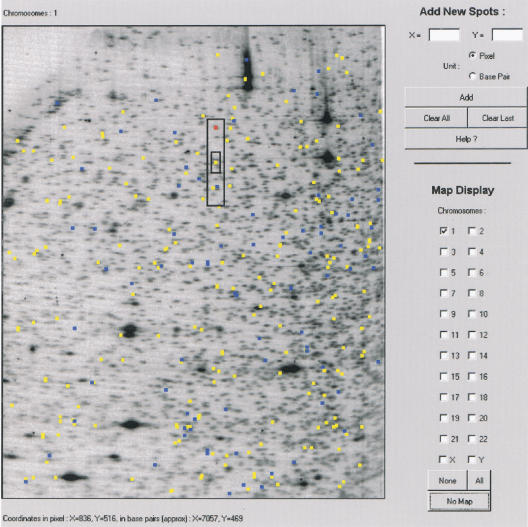

Figure 1 shows, as background for the VGS display interface, a NotI/EcoRV/HinfI RLGS profile of a human B lymphoblastoid cell line. Most of the intense spots in this pattern are derived from the 44-kb rDNA sequence that is tandemly repeated ∼40 times on each of the five acrocentric chromosomes. The other intense fragments are derived from the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) genome. We have deduced the restriction maps for both rDNA and EBV, from their known sequence in prior studies (Kuick et al. 1996). Thus, we utilized the location of these fragments as internal standards for estimating the size of fragments in RLGS patterns based on their pixel position as described in Methods. This also allowed us to compute pixel positions of all the fragments predicted from the human genome sequence. The resulting graphs represent VGS patterns that matched RLGS patterns in fragment size separation range. For example, the human chromosome 1 virtual pattern is shown in Figure 1 superimposed onto a whole genome RLGS pattern.

Figure 1.

Whole genome restriction landmark genomic scanning (RLGS) pattern superimposed with a chromosome 1 virtual genome scanning (VGS) profile, both obtained using the NotI/EcoRV/HinfI enzyme combination. (Yellow, draft sequence; blue, finished sequence). Instructions for use of the software are accessed by clicking the Help button. The red spot represents the experimental ALX3 spot described in Table 1. The small rectangle centered on the predicted ALX3 spot (yellow) represents the area encompassing 75% of the predicted-experimental spot pairs, and the larger rectangle encompasses 100% of these pairs.

Prediction of Fragments in RLGS Patterns by Comparison with VGS Patterns

The utility of VGS was evaluated by testing whether the informatics tools we have developed could predict the sequences for 29 fragments of interest in RLGS patterns, for which we have obtained sequence information experimentally (Table 1). Eight of these fragments represented restriction fragment length polymorphisms detected in RLGS scans. Such polymorphisms are of particular interest as they occur in or near CpG islands, in the vicinity of coding sequences. Six of the eight fragments were predicted correctly from the VGS database. Two of the eight polymorphisms were not predicted as their corresponding sequence in GenBank was incomplete and did not encompass both NotI and EcoRV sites.

Table 1.

Correspondence Between Migration and Predicted Pixel Location

| Type of variations | HinfI exp.1D/2D | HinfI Predicted 1D/2D | DpnII exp.1D/2D | DpnII Predicted 1D/2D | Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphism | 647/504 | 645/493 | NA | NA | Polymorphism on chr 17 |

| 582/386 | 578/390 | NA | NA | Polymorphism on chr 3 | |

| 524/628 | 514/620 | NA | NA | Polymorphism on chr 19 | |

| 528/307 | 528/318 | NA | NA | Polymorphism on chr 21 | |

| 669/225 | 680/278 | NA | NA | Polymorphism on chr 13 | |

| 704/188 | 714/252 | NA | NA | Polymorphism on chr 14 | |

| 395/390 | NP | NA | NA | Polymorphism on chr 9 | |

| 749/198 | NP | NA | NA | Polymorphism on chr 4 | |

| Deletion | 447/581 | 443/566 | NA | 463/666 | TP73 |

| 402/550 | 405/544 | NA | 426/1023 | Expected P73 | |

| 582/517 | 576/510 | NA | 587/362 | Expected P73 | |

| Methylation | 568/333 | 568/385 | NA | 579/1023 | ALX3 |

| 675/480 | NP | NA | NA | RPA2 | |

| 602/453 | 596/448 | 603/441 | 605/441 | NBL3 | |

| 402/787 | 393/776 | 414/779 | 414/783 | NBL2 | |

| NA | 393/1008 | 417/651 | 414/653 | NBL2 | |

| Amplification | 257/574 | 253/566 | NA | 277/816 | ODC1 |

| 258/658 | 253/664 | NA | 277/901 | ODC1 | |

| 368/608 | 371/610 | 384/890 | 393/868 | NAG1 (NBA-2A | |

| NA | 747/1023 | 742/549 | 745/458 | NAG1 (NBA-2B) | |

| 367/618 | NP | 388/724 | NP | NBA-1A | |

| 779/603 | NP | 771/695 | NP | NBA-1B | |

| NA | 656/1023 | 651/679 | 660/692 | DDX1 (NBA-3) | |

| 595/672 | 592/673 | NA | 602/1023 | DDX1-B |

Correspondence between migration and predicted pixel location in the first and second dimensions (1D/2D) for a set of fragments that exhibited biological variation in RLGS patterns. The sequence identity of these fragments was determined experimentally.

NA, data not available.

DP, no prediction because of insufficient sequence data in the genome database.

We have previously undertaken an RLGS analysis of genomic amplification in neuroblastomas (Wimmer et al. 1999). Among the 11 amplified fragments observed by RLGS (six in HinfI and five in DpnII patterns), we successfully predicted seven (Table 1). Four fragments (two in DpnII patterns designated NBA-1A and NBA-1B (Wimmer et al. 2001) and their two HinfI counterparts) that were cloned and which were derived from the same NotI site, could not be predicted as their sequence was not yet available from the human genome project.

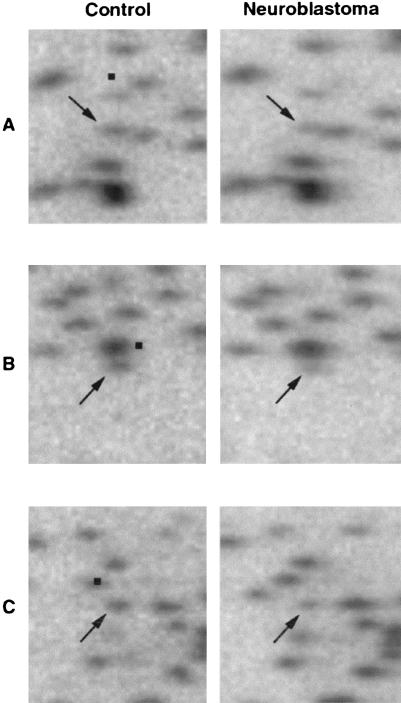

We also undertook an analysis of RLGS patterns of 13 neuroblastoma tumors for alterations involving chromosome 1 fragments. Three fragments that we have assigned to chromosome 1 (Wimmer et al. 1996) were concomitantly reduced in intensity in the same six tumors, compared to controls, suggesting they could be located close to each other on chromosome 1 (Fig. 2). One of the fragments (spot A) was cloned and sequenced. Database searches using the BLAST search engine showed a perfect homology with a sequence in GenBank (AB031234) that contains the promoter region and exon 1 of the TP73 gene (Ding et al. 1999). This fragment was predicted successfully using VGS. The corresponding genome sequence (GenBank NT_004068, 138941 bp) occurred in a region that contained two NotI sites that predicted a correspondence with the two additional fragments (Fig. 2B,C) in our RLGS patterns that were concomitantly reduced in intensity with fragment A. Two other fragments that showed frequently diminished intensity in neuroblastomas versus controls were cloned and identified as ALX3 and RPA2 (K. Wimmer, X.-X. Zhu, J.-M. Rouillard, P. Ambros, B. Lamb, R. Kuick, M. Eckart, A. Weinhäusl, C. Fonatsch, and S. Hanash, in prep.). VGS successfully predicted ALX3 (Fig. 1), whereas RPA2 was not predicted because its corresponding sequence available from the human genome project was incomplete and too short to contain both NotI and EcoRV sites needed to compute a first-dimension size.

Figure 2.

Close-up sections of restriction landmark genomic scanning (RLGS) patterns containing chromosome 1 derived spots A–C (arrows) with reduced intensity in neuroblastoma STA-NB9 cell line relative to control peripheral blood lymphocytes. The location of matching fragments in virtual genome scanning (VGS) patterns is indicated with black squares. RLGS patterns were obtained using the NotI/EcoRV/HinfI enzyme combination.

NotI site methylation results in loss of the corresponding fragment(s) from RLGS patterns. We previously cloned and sequenced two fragments that occurred at an intensity corresponding to multiple copies in the genome in NotI/EcoRV/HinfI patterns of neuroblastomas that were absent in RLGS patterns of normal controls. These fragments, which were designated NBL2 and NBL3, were found to undergo demethylation in neuroblastoma (Thoraval et al. 1996b). VGS successfully predicted both fragments (Table 1).

A total of 22 of the 29 fragments were predictable from the VGS database. There were precise correspondence between expected location and actual migration of fragments in the first dimension and a slightly less precise correspondence in the second dimension, which was not limited to any particular fragment size range (e.g., large or small fragments). As a result, the predicted location of fragments is covered in a narrow first-dimension zone and a slightly wider second-dimension zone. Thus, by examining the correspondence between RLGS and VGS for a set of known fragments, we have determined for HinfI profiles that 75% of the fragments were located in a rectangular area that spanned 12 pixels in the first dimension and 30 pixels in the second dimension. The remaining 25% was located in an area that spanned 24 pixels in the first dimension and 128 pixels in the second dimension (Fig. 1, rectangle).

We have developed interactive informatics tools to provide a user-friendly interface for automated RLGS fragment prediction and for downloading of the corresponding sequence in the genome. Users can directly query our database through this interface from the VGS Web site (http://dot.ped.med.umich.edu:2000/VGS/index.html). An overall view of the interface is given in Figure 1.

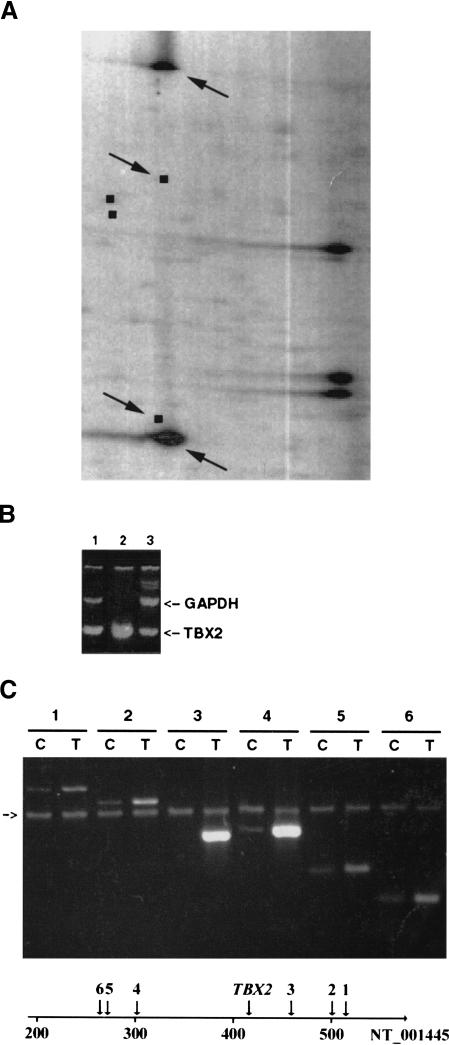

Utilization of VGS to Characterize a Highly Amplified Region on 17q23 in a Breast Tumor

Several groups have uncovered genomic amplification involving 17q23 in breast tumors and cell lines (Muleris et al. 1995; Barlund et al. 1997; Tirkkonen et al. 1998; Couch et al. 1999). There is evidence that multiple genes on 17q23 may be the targets of amplification (Barlund et al. 2000). In our analysis of breast tumors and cell lines by RLGS, one breast tumor (Tumor 200) that was found by comparative genomic hybridization to exhibit 17q23 amplification (Muleris et al. 1995), presented a unique NotI/EcoRV/HinfI profile in which two fragments were highly amplified (Fig. 3A). Amplification of the two fragments in Tumor 200 was estimated at 200 copies each in the tumor genome, based on quantitative analysis of their RLGS spot intensity. Given that chromosome 17 was represented by several hundred fragments in RLGS patterns and that only two fragments were amplified in Tumor 200, this tumor provided an opportunity to delineate a small region of amplification. The two fragments had identical migration in the first dimension, suggesting that they were derived from the same NotI–NotI fragment. Two amplified fragments with similar migration characteristics in the first-dimension were also observed in DpnII-based separations of genomic DNA from this tumor (data not shown). We and others have assigned chromosomal identity to most fragments observed in RLGS patterns (Wimmer et al. 1996; Yoshikawa et al. 1996; Curtis et al. 1998). The amplified fragments observed in the breast tumor were clearly derived from chromosome 17. Our VGS tools yielded a unique match for the two amplified fragments consistent with their occurrence as part of a NotI–NotI fragment in the first dimension (NotI sites in positions 414373 and 417881 in sequence NT_001445)(Fig. 3A). Two additional fragments with a first dimension size of 15,649 and 21,903 bp were predicted. Their absence in RLGS patterns is attributable to the limited first-dimension size range (1–6 kb) of the RLGS patterns we have analyzed. A BLAST search uncovered identity of the NotI/NotI fragment with the 5′ end of TBX2 mRNA (HSU28049). The TBX2 gene maps to 17q23 and has been shown recently to be encompassed in relatively large amplicons spanning this region in some tumors and cell lines including MCF7 (Barlund et al. 2000; Jacobs et al. 2000). We have confirmed the identity of the fragment by semiquantitative duplex PCR (see Methods), which showed that the TBX2 sequence was amplified in the tumor relative to control DNA (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Tumor 200 NotI/EcoRV/HinfI restriction landmark genomic scanning (RLGS) profile. Black squares represent predicted spots from chromosome 17 in this section of the RLGS pattern. Arrows point to two amplified fragments specific to Tumor 200 and to the location of their predicted fragments from chromosome 17. The three highly intense spots in the right part of the gel represent rDNA. (B) PCR analysis of TBX2 genomic amplification. Lane 1: MCF7; lane 2, Tumor 200; lane 3, Control DNA. Arrows point to GAPDH (407 bp) and TBX2 (188 bp) PCR products. (C) Extent of the 17q23 amplified region as determined by PCR analysis. Lanes 1– 6 represent multiplexed PCR using GAPDH and primers 1–6, respectively (C, control DNA; T, Tumor 200 DNA). An arrow points to the location of GAPDH (407 bp) PCR product. Positions of primer pairs 1–6 and TBX2 along sequence NT_001445 are drawn. The scale is given in kb.

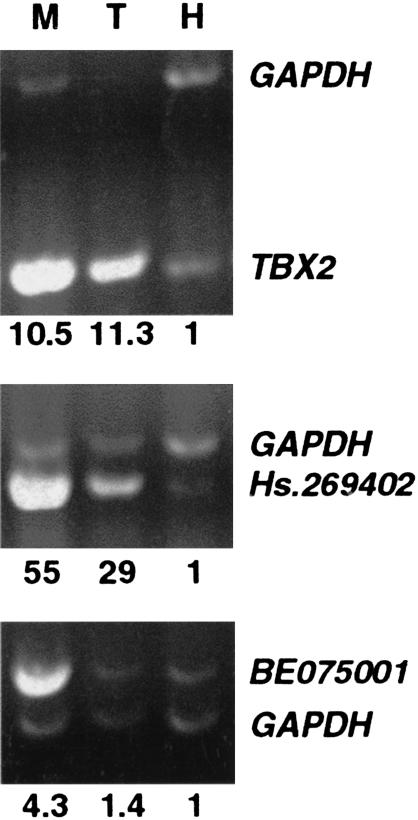

The TBX2 related fragments exhibited high-level amplification in the breast tumor. Furthermore, no additional 17q23 derived fragments were observed in RLGS patterns of the tumor, including lack of detectable amplification of fragments encompassing a NotI site present at position 738509 in NT_001445. These findings suggested the occurrence of a small amplicon in this tumor. To delineate the extent of this amplicon, we designed 15 pairs of primers that were spaced regularly on each side of the TBX2-amplified fragments for PCR analysis (six are presented in Fig. 3C). Based on the PCR results, a highly amplified region spanning <228 kb was delineated. Using BLAST, we found two EST clusters, in addition to TBX2, in this amplicon. The first occurred ∼55 kb from TBX2, and corresponded to the UniGene cluster Hs.269402 containing three ESTs, two of which were derived from breast tissue libraries. The second occurred ∼85 kb from TBX2, and contained four ESTs in the opposite direction, also from breast tissue libraries (GenBank BE075001 for example). We determined the expression level of TBX2 and of the two clusters of ESTs by semiquantitative RT–PCR (Fig. 4) in Tumor 200 and in MCF7. The HPV11–21 breast cell line that does not contain 17q23 amplification was used as a control. TBX2 was overexpressed in MCF7 compared to control, as reported previously (Barlund et al. 2000). It was also overexpressed in Tumor 200 relative to control. Similarly, UniGene cluster Hs.269402 was overexpressed in both MCF7 cell line and Tumor 200 compared to control. EST BE075001 was overexpressed in MCF7 cell line but not in Tumor 200.

Figure 4.

Semiquantitative RT–PCR analysis of TBX2 gene (188 bp), Hs.269402 UniGene cluster (323 bp) and BE075001 EST (486 bp). Total RNA from Tumor 200 (T), MCF7 (M), and the control HPV11–21 (H) cell line was utilized. GAPDH (407 bp) was coamplified as a control. Numbers given below lanes represent fold intensity for MCF7 and Tumor 200 vs. HPV11–21.

DISCUSSION

We have devised an efficient approach for predicting the identity of genomic fragments detected in RLGS profiles, based on their correspondence with fragments of similar size characteristics displayed in VGS scans computed from the human genome sequence. Previously, a major bottleneck in RLGS analysis was the need for cloning strategies to identify fragments of interest. The small amount of DNA extractable, for most fragments in RLGS gels, substantially limits identification of these fragments by gel extraction. NotI/EcoRV library construction has facilitated fragment identification. In one strategy, based on an arrayed library (Smiraglia et al. 1999), 1789 RLGS fragments were assigned to unique library clones. However, coverage remained limited primarily because of relatively small-sized fragments and was restricted based on the choice of enzyme(s) used to construct the library from genomic DNA. Additionally in the case of NotI, library coverage is limited to NotI sites that were unmethylated in the genomic DNA from which the library was prepared. Computational prediction of RLGS profiles from genome sequence data overcomes these limitations. A similar approach has been applied to yeast for high-resolution hybridization analyses using megabase stretches of known DNA sequences as a reference (Qiu et al. 1997). The approach we have developed is applicable to all species for which genome sequences are available. This tool substantially enhances the utility of RLGS for genome scanning for methylation analysis, for the detection of polymorphisms in CpG islands, and for the analysis of genomic alterations in cancer.

We observed a good correlation between the experimental and predicted fragment location in the first dimension. However, a few fragments in our study exhibited seemingly aberrant migration in the second dimension, suggesting that parameters additional to DNA fragment size may affect mobility. Qiu et al. (1997) reported that a 180° bend in a DNA fragment leads to a discrepancy between expected and apparent migration of a DNA fragment on RLGS. Other parameters such as GC content and methylation status may affect DNA mobility. The occurrence of unrecognized sequence polymorphisms could also explain some discrepancies between virtual and experimental maps in either first or second dimension.

The availability of two different profiles for a sample as with the use of either HinfI or DpnII in the second dimension has utility in determining among candidates, the correct fragment in VGS. When two lists of candidates obtained from HinfI and DpnII patterns are compared, only common candidates have to be considered. It is unlikely that multiple candidates will match a particular fragment in both HinfI and DpnII patterns. Alternatively, assignment of a fragment observed in an RLGS pattern to a particular chromosome substantially reduces the likelihood that multiple candidates occur in the VGS database. Only candidates derived from one chromosome, or few chromosomes in the case of ambiguities, need to be considered. VGS help allows us to predict a sequence or to narrow the list of candidates for a given spot. Any prediction may need to be confirmed. Direct access to sequences allows, for example, PCR-based testing to determine which candidate's oligonucleotide primers yield a PCR product from the gel-extracted DNA fragment of interest.

The utility of RLGS in combination with VGS was demonstrated by the identification of fragments that exhibited NotI site methylation or that were deleted in neuroblastomas and the identification of fragments involved in amplifications in neuroblastoma or in breast tumors. The amplified 17q23 region we have delineated may represent a minimal critical region for amplification in breast cancer, given its small size and its very high level of amplification in Tumor 200. This does not exclude that other minimal critical regions may occur in 17q23 as suggested in other studies (Barlund et al. 1997). The occurrence of EST's within this region that were expressed in breast lineage is of interest as the corresponding genes may be of relevance to breast tumorigenesis.

In our study, 75% (22/29) of the tested fragments were predictable using VGS tools. The inability to predict the remaining fragments was attributable to their sequence occurring in multiple, as yet unassembled, sequences in the draft genome sequence, or due to their (as yet) lack of sequence. We can expect that with the completion of the human genome sequencing effort, the vast majority of fragments will be predictable using VGS.

The VGS approach substantially overcomes the prior difficulty in deriving sequence information for fragments displayed in RLGS patterns. This should facilitate a widespread use of RLGS for comparative whole-genome scanning.

METHODS

Human Genome Sequence

The finished sequence was downloaded in FASTA format from the GenBank site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/seq/). The draft sequence was downloaded in GenBank format based on the keywords HTGS_PHASE1 or HTGS_PHASE2. Comments were parsed to split sequence entries containing more than one piece in as many FASTA sequences as there were pieces present. Entries without chromosome assignment were discarded at this step.

Cell Lines and Tumors

STA-NB9 neuroblastoma cell line (Ambros et al. 1997) was obtained from Children's Cancer Research Institut (Vienna, Austria). MCF7 breast cancer cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection. HPV11–21 (Ethier et al. 1993), a human papilloma virus immortalized nontumorigenic mammary cell line, was developed at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

RLGS and PCR

A detailed description of the RLGS experimental conditions can be found in Hatada et al. (1991) and Asakawa et al. (1994). PCR primers 1–6 were designed using NT_001445 sequence. The position on this sequence of the first base of each primer is given in parenthesis. 1F (514654) aacaggggttttacagcagtct, 1R (515170) aaacaaaaggggtgggttctgt, 2F (500747) tacaccagc tatagcgtgcaga, 2R (501195) ctgtgtttcttggtagagtgca, 3F (458906) cacatggtcttagctgggggta, 3R (459229) ggggcaaatag atttgcaggta, 4F (302579) tcctggttctcctgtctgtagg, 4R (302913) cagggactctgccgtgcact, 5F (272689) agctgtaattgtcacagggaga, 5R (272916) ccttgtcgggtgacctggaga, 6F (264458) gatgttttccat gagcctgatg, 6R (264626) ggaaataaccctttgagccact. TBX2 and GAPDH primers are described below. One hundred ng of control or Tumor 200 DNA were used in a 20 μL PCR reaction using 100 ng of each primer and 40 ng of each GAPDH primer. For primers 1, 3, and 4, 20 cycles were done. For primers 2, 5, and 6, three cycles were done without GAPDH primers and then these primers were added for 20 more cycles. Ten μL of PCR reaction were loaded on a 2% agarose gel.

Semiquantitative PCR was done using primers: TBX2 F, ggtgcagacagacagtgcgt; R, aggccagtaggtgacccatg; Hs.269402 F, aggatgattttggcaggtga; R, ctcccctttcgcttccttcca; BE075001 F, caagcactgccagcctgtga; and R, tcttacccgctctcagagagga.

Gene of interest was duplexed with internal control GAPDH F: gggagccaaaagggtcatca, R: tttctagacggcaggtcaggt.

Virtual Map Computation

For each known spot on a master image (rDNA- and EBV-derived spots), coordinates in pixels for first and second dimension, respectively, were plotted against first- and second-dimension fragments sizes deduced from the sequence data. The two cubic polynomial curves fitting these points were used to compute the pixel coordinates of each virtual spot on the master image.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant CA26803 and by grants from a Programme Incitatif et Cooperatif de L'Institut Curie “genetique et biologie des cancers du sein”. J.M.R. was supported by a grant from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer. A.E.E. was supported by a grant from Higher Education Council of Turkey. K.W. was supported by an Austrian grant of the Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung nr. (P12942-GEN).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL shanash@med.umich.edu; FAX (734) 649-8148.

Article published on-line before print: Genome Res., 10.1101/gr.181601.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.181601.

REFERENCES

- Ambros IM, Rumpler S, Luegmayr A, Hattinger CM, Strehl S, Kovar H, Gadner H, Ambros PF. Neuroblastoma cells can actively eliminate supernumerary MYCN gene copies by micronucleus formation–sign of tumour cell revertance? Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:2043–2049. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa J, Kuick R, Neel JV, Kodaira M, Satoh C, Hanash SM. Genetic variation detected by quantitative analysis of end-labeled genomic DNA fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:9052–9056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlund M, Tirkkonen M, Forozan F, Tanner MM, Kallioniemi O, Kallioniemi A. Increased copy number at 17q22-q24 by CGH in breast cancer is due to high-level amplification of two separate regions. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1997;20:372–376. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199712)20:4<372::aid-gcc8>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlund M, Monni O, Kononen J, Cornelison R, Torhorst J, Sauter G, Kallioniemi O-P, Kallioniemi A. Multiple genes at 17q23 undergo amplification and overexpression in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5340–5344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corn PG, Kuerbitz SJ, van Noesel MM, Esteller M, Compitello N, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Transcriptional silencing of the p73 gene in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Burkitt's lymphoma is associated with 5′ CpG island methylation. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3352–3356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch FJ, Wang XY, Wu GJ, Qian J, Jenkins RB, James CD. Localization of PS6K to chromosomal region 17q23 and determination of its amplification in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1408–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis LJ, Li Y, Gerbault-Seureau M, Kuick R, Dutrillaux AM, Goubin G, Fawcett J, Cram S, Dutrillaux B, Hanash S, et al. Amplification of DNA sequences from chromosome 19q13.1 in human pancreatic cell lines. Genomics. 1998;53:42–55. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Inoue T, Kamiyama J, Tamura Y, Ohtani-Fujita N, Igata E, Sakai T. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of the upstream promoter region of the human p73 gene. DNA Res. 1999;6:347–351. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.5.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng C, Herman JG, Baylin SB. A bird's eye view of global methylation [news; comment] Nat Genet. 2000;24:101–102. doi: 10.1038/72730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier SP, Mahacek ML, Gullick WJ, Frank TS, Weber BL. Differential isolation of normal luminal mammary epithelial cells and breast cancer cells from primary and metastatic sites using selective media. Cancer Res. 1993;53:627–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SG, Lerman LS. Length-independent separation of DNA restriction fragments in two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Cell. 1979;16:191–200. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatada I, Hayashizaki Y, Hirotsune S, Komatsubara H, Mukai T. A genomic scanning method for higher organisms using restriction sites as landmarks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:9523–9527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsune S, Shibata H, Okazaki Y, Sugino H, Imoto H, Sasaki N, Hirose K, Okuizumi H, Muramatsu M, et al. Molecular cloning of polymorphic markers on RLGS gel using the spot target cloning method. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;194:1406–1412. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JJ, Keblusek P, Robanus-Maandag E, Kristel P, Lingbeek M, Nederlof PM, van Welsem T, van de Vijver MJ, Koh EY, Daley GQ, et al. Senescence bypass screen identifies TBX2, which represses Cdkn2a (p19(ARF)) and is amplified in a subset of human breast cancers. Nat Genet. 2000;26:291–299. doi: 10.1038/81583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, LaQuaglia MP, Yang SY. A cDNA encoding a putative 37 kDa leucine-rich repeat (LRR) protein, p37NB, isolated from S-type neuroblastoma cell has a differential tissue distribution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1309:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(96)00158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuick R, Asakawa J, Neel JV, Satoh C, Hanash SM. High yield of restriction fragment length polymorphisms in two-dimensional separations of human genomic DNA. Genomics. 1995;25:345–353. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80032-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuick R, Asakawa J, Neel JV, Kodaira M, Satoh C, Thoraval D, Gonzalez IL, Hanash SM. Studies of the inheritance of human ribosomal DNA variants detected in two-dimensional separations of genomic restriction fragments. Genetics. 1996;144:307–316. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.1.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen F, Gundersen G, Lopez R, Prydz H. CpG islands as gene markers in the human genome. Genomics. 1992;13:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90024-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay S, Bird AP. Use of restriction enzymes to detect potential gene sequences in mammalian DNA. Nature. 1987;327:336–338. doi: 10.1038/327336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muleris M, Almeida A, Gerbault-Seureau M, Malfoy B, Dutrillaux B. Identification of amplified DNA sequences in breast cancer and their organization within homogeneously staining regions. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;14:155–163. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870140302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu P, Kupfer KC, Garrard WT. A method for genome comparisons and hybridization studies using known megabase-scale DNA sequences as a reference. Genomics. 1997;43:307–315. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiraglia DJ, Fruhwald MC, Costello JF, McCormick SP, Dai Z, Peltomaki P, O'Dorisio MS, Cavenee WK, Plass C. A new tool for the rapid cloning of amplified and hypermethylated human DNA sequences from restriction landmark genome scanning gels. Genomics. 1999;58:254–262. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Kawai J, Taga C, Ozawa N, Watanabe S. A PCR-mediated method for cloning spot DNA on restriction landmark genomic scanning (RLGS) gel. DNA Res. 1994;1:245–250. doi: 10.1093/dnares/1.5.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoraval D, Asakawa J, Kodaira M, Chang C, Radany E, Kuick R, Lamb B, Richardson B, Neel JV, Glover T, et al. A methylated human 9-kb repetitive sequence on acrocentric chromosomes is homologous to a subtelomeric repeat in chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996a;93:4442–4447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoraval D, Asakawa J, Wimmer K, Kuick R, Lamb B, Richardson B, Ambros P, Glover T, Hanash S. Demethylation of repetitive DNA sequences in neuroblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1996b;17:234–244. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199612)17:4<234::AID-GCC5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirkkonen M, Tanner M, Karhu R, Kallioniemi A, Isola J, Kallioniemi OP. Molecular cytogenetics of primary breast cancer by CGH. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998;21:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitterlinden AG, Slagboom PE, Knook DL, Vijg J. Two-dimensional DNA fingerprinting of human individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:2742–2746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer K, Thoraval D, Asakawa J, Kuick R, Kodaira M, Lamb B, Fawcett J, Glover T, Cram S, Hanash S. Two-dimensional separation and cloning of chromosome 1 NotI-EcoRV-derived genomic fragments. Genomics. 1996;38:124–132. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer K, Zhu XX, Lamb BJ, Kuick R, Ambros PF, Kovar H, Thoraval D, Motyka S, Alberts JR, Hanash SM. Co-amplification of a novel gene, NAG, with the N-myc gene in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 1999;18:233–238. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer K, Zhu XX, Lamb BJ, Kuick R, Ambros P, Kovar H, Thoraval D, Elkahloun A, Meltzer P, Hanash SM. Two-dimensional DNA electrophoresis identifies novel CpG islands frequently coamplified with MYCN in neuroblastoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;36:75–79. doi: 10.1002/1096-911X(20010101)36:1<75::AID-MPO1018>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, de la Monte S, Nagai H, Wands JR, Matsubara K, Fujiyama A. Chromosomal assignment of human genomic NotI restriction fragments in a two-dimensional electrophoresis profile. Genomics. 1996;31:28–35. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]